Abstract

Emerging evidence indicates that suppression of protein kinase C (PKC) renders the susceptibility of cells expressing mutated ras to apoptosis. Although the effort has been made, the underlying molecular mechanisms are not fully understood. Here, using shRNAs or PKC inhibitor, we demonstrate that the concurrent suppression of PKC α and β induces cells ectopically expressing v-ras to undergo apoptosis. In this apoptotic process, PKC δ is upregulated and translocated from the cytosol to the nucleus. The activated PKC δ associates with and phosphorylates p73 to initiate apoptosis. In this apoptotic process, Akt appears to be downstream of oncogenic Ras. Moreover, overexpression of PKC δ, without co-suppression of PKC α and β, is not apoptotic to the cells, suggesting that PKC δ and α/β function oppositely to facilitate cells harboring v-ras to survive. Thus, our study demonstrates that PKC α and β are necessary for sustaining the homeostasis in cells containing a hyperactive Ras. The abrogation of these two isoforms switches on the p73-regulated apoptotic machinery via the activation of PKC δ.

Keywords: PKC isoforms, oncogenic Ras, p73, apoptosis

Introduction

PKC, a family of serine/threonine protein kinases, consists of more than 10 isoforms that differ in their structures, cellular functions and tissue distributions (Nishizuka et al., 1995; Gutcher et al., 2003; Spitaler and Cantrell, 2004). PKC α, βI, βII and γ are categorized as the conventional or classic PKC isoforms that are calcium- and diacylglycerol (DAG)-dependent for the activation, while isozymes of unconventional PKC subgroup (PKC δ, ε, η and θ) are independent of calcium for their functions. The atypical PKC isozymes (PKC ζ and λ/ν) require neither DAG nor calcium for being activated. The structural diversity and different tissue distributions render distinct specificities of PKC isozymes that differentially regulate various cellular signaling pathways and further dictate different biological outcomes, including apoptosis. Recently, with the availability of small hairpin RNA (shRNA) and other genetic means to disrupt individual PKC isoform in vitro and in vivo, studies demonstrated that PKC isoforms are either pro- or anti-apoptotic, depending upon cell types, stimuli or contexts within signaling pathways (Matassa et al., 2001; Gutcher et al., 2003; Brodie and Blumberg, 2003;Reyland, 2007).

Ras family consists of a group of small GTPases (including three major members: Ha-, Ki and N-Ras) that, via governing various downstream effectors, regulate diverse cellular biological processes, including proliferation, differentiation, motility, transformation and apoptosis. In about 30% of human malignancies, Ras proteins are mutated. The active, GTP-bound form of Ras interacts with its downstream effectors and stimulates their activities. The balance among different intracellular signaling pathways is a key element to determine the fate of cells. Under conditions of stresses (such as downregulation of endogenous PKC activity, loss of matrix adhesion, or tamoxifen treatment), active Ras in lymphocytes or fibroblasts promoted apoptosis (Chen et al., 1998a). Apoptosis initiated by mutated Ras appeared to involve multiple downstream signaling pathways (Chen et al., 1998b). The effort to determine the downstream effectors of Ras in transmitting pro-apoptotic signaling has been made. For example, overexpression of Raf renders mouse fibroblasts the susceptibility to apoptosis (Wang et al., 1998). Sustained activation of MAP kinase pathway in Swiss3T3 cells was linked to the induction of apoptosis (Fukasawa et al., 1995). Oncogenic Ras was also shown to utilize JNK and PI3K/Akt pathways to execute cell death program (Chen et al., 2001; Guo et al. 2009). Recently, using large-scale RNA interference screens, it was demonstrated the kinase-dependent vulnerabilities of cancers harboring oncogenic K-ras (Scholl et al. 2009; Luo et al. 2009).

PKC δ is a multifunctional kinase that is expressed in various tissues. Using the knockout mouse model, studies showed that PKC δ plays an important role in controlling diverse cell activities, including cell proliferation (Li et al., 1998; Kiley et al., 1999; Braun and Mochly-Rosen, 2003; Jackson and Foster, 2004), immune responses, migration and apoptosis (Li et al., 1999; Brodie et al., 2003; Eitel et al., 2003; Kajimoto et al., 2004; Murriel et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2004; Atten et al., 2005; Kheifets et al., 2006). However, the role of PKC δ in the regulation of apoptosis is rather controversial. This isoform of PKC was shown to be required for insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) receptor-mediated transformation (Li et al., 1998). Inhibition of PKC δ was shown to sensitize several v-Ki- or Ha-ras expressing cells to apoptosis (Xia et al., 2007). However, other studies demonstrated that this serine/threonine kinase is a critical pro-apoptotic factor in apoptosis induced by different apoptotic stimuli. For example, PKC δ confers the susceptibility of human glioma or myeloma cells to apoptosis induced by anti-cancer drugs (Mandil et al., 2001; Ni et al., 2003). The activation of this PKC isoform was also required for cell death induced by UV-irradiation, genotoxins, brefeldin A and death receptor (Emoto et al., 1995; Emoto et al., 1997; Mizuno et al., 1997; Reyland, 1997; Matassa et al., 2001). Moreover, it was reported that although PKC δ null mice are not susceptible to cancer, the numbers of smooth muscle cells in the mice are increased, and they are resistant to genotoxins and other apoptotic stimuli (Humphries et al., 2006).

Upon apoptotic stimulation, PKC δ was activated and subsequently translocated to the nucleus (Emoto et al., 1995; Emoto et al., 1997; Kaul et al., 2003). Ectopic expression of the active PKC δ alone was sufficient to trigger apoptosis, even under the condition lacking apoptotic stimulation. In the process, PKCδ was associated with apoptotic factors, such as Bax and further activate them for the induction of apoptosis (Denning et al., 2002; Sitailo 2004). Loss of functional mutations of PKC δ blocks its nuclear translocation as well as its ability to induce apoptosis (Ghayur et al., 1996; DeVries-Seimon et al., 2007). In particular, the introduction of a kinase dead PKCα mutant caused salivary epithelial cells to undergo apoptosis in a PKC δ-dependent fashion (Matassa et al. 2003). In this apoptotic process, JNK was activated, accompanied with an increased of caspase 3 activity.

p53 exerts its tumor suppression function through controlling cell cycle checkpoints and regulating apoptosis (Levine et al., 1997). p73 and p63 belong to p53 family and share homology with p53 in not only their sequence but also their transactivation, DNA-binding and oligomerization functions. These two p53-related molecules have been shown to be able to activate p53-responsive genes in a p53-independent fashion. Studies also showed that p73 is involved in the cellular response to DNA damage or genotoxic stress (Jost et al., 1997; Yang et al., 2002). For example, in response to DNA damage, the activated PKC δ was able to bind to and phosphorylate p73, leading to apoptosis (Ren et al., 2002).

In this study, the experiments showed that mutated Ras, together with concurrent suppression of PKC α and β, were apoptotic. In this apoptotic process, PKC δ was upregulated and translocated to the nucleus. The active PKC δ then interacted with and activated p73 for the induction of apoptosis. However, overexpression of PKC δ without suppression of PKC α/β is not lethal, suggesting that PKC δ and α/β might function oppositely to maintain homeostasis in the cellular environment controlled by hyperactive Ras.

Results

Concurrent suppression of PKC α and β induces apoptosis in the cells with aberrant Ras signaling

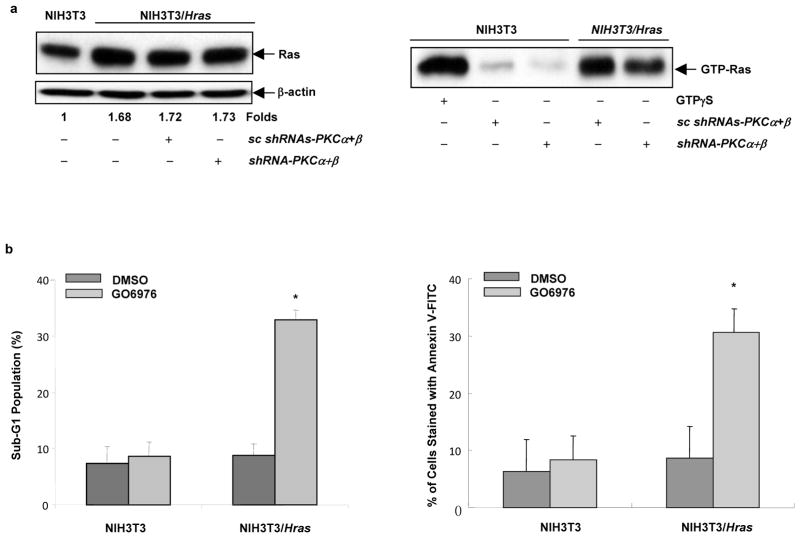

The addition of GO6976 (a potential PKC α and β inhibitor) induced various types of cells expressing an active ras to undergo apoptosis (Guo et al., 2009). The suppression of PKC α by a kinase dead PKCα mutant was also reported to render salivary epithelial cells the susceptibility to PKC δ-dependent apoptosis (Matassa et al. 2003). Since GO6976 was shown to affect the activity of other types of serine/threonine kinases (for example, Chk1) (Aaltonen et al. 2007), in order to identify which PKC isozymes are necessary for the induction of apoptosis, the shRNAs against PKC α and β were used. Murine NIH3T3 cells were first stably infected v-Ha-ras (designated as NIH3T3/Hras) and afterwards the expression of Ras was tested by immunoblotting (Figure 1a, left panels). NIH3T3/Hras cells expressed an increased amount of Ras and the relative expression of the protein to the control was determined by densitometry. The activation status of Ras was also measured by the Active Ras Pull-Down and Detection kit, in which increased GTP bound Ras was only detected in NIH3T3/Hras cells, but not in the parental cells (Figure 1a, right panels). As the confirmation purpose, the induction of apoptosis by GO6976 in thees cells was examined by DNA fragmentation (Figure 1b, left panel) and Annexin V-FITC apoptotic detection (Figure 1b, right panel) assays. Consistently, after treated with the inhibitor for 48 h, more than 30% of NIH3T3/Hras cells underwent apoptosis, and very low numbers of the parental cells were apoptotic. The data indicate that GO6976 is able to induce apoptosis and PKC α and β might be the potential targets for sensitizing cells expressing v-ras to apoptosis.

Figure 1.

Induction of apoptosis in NIH3T3/Hras cells after suppression of PKC. (a) Ras expression and activation status in NIH3T3 and NIH3T3/Hras cells. Left panels: the cells, with or without transiently co-infected with shRNA-PKCα and β or scrambled shRNAs for 48 h, were lysed and immunoblotted with anti-Ras antibody. The relative expression level of proteins was normalized by β-actin and presented as n-fold. Right panel: cell lysates were also assayed for Ras activity. GTPγS-treated lysate was a positive control. (b) Cells were treated with PKC inhibitor GO6976 (1 μM) or DMSO (control) for 48 h and then assayed by DNA fragmentation and Annexin V-FITC assays. Subsequently, the percentages of the cells with sub-G1 DNA content or stained positively with AnnexinV-FITC were plotted. The error bars are SD (standard deviation) of 5 independent experiments (n = 5, *, p < 0.05).

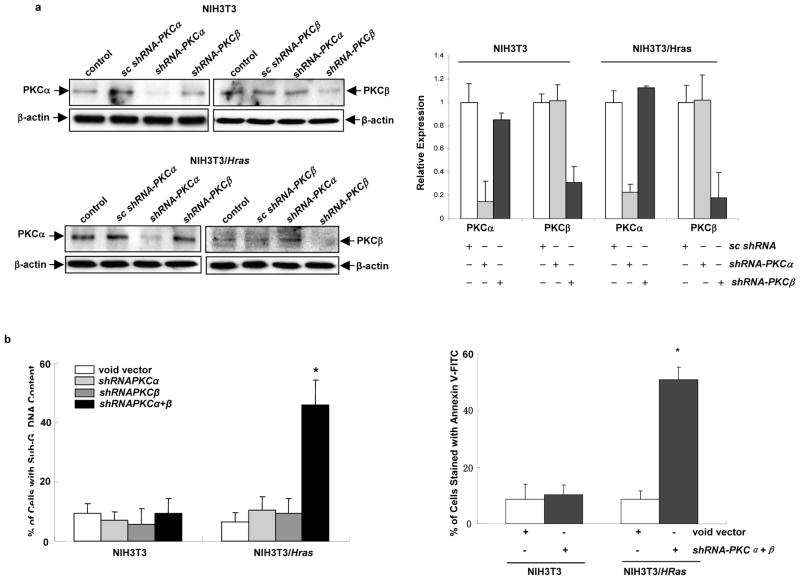

To determine whether suppression of PKC α and β is necessary for the initiation of apoptosis, the shRNAs targeting PKC α, β and corresponding scrambled shRNAs were transiently infected into the cells. The knockdown of the expression of these two PKC isoforms by the shRNAs was examined by immunoblotting (Figure 2a, left panels). The level of PKC α was dramatically knocked down by the shRNA, but not by shRNA-PKCβ or scrambled shRNA. The similar phenomenon was seen in the knockdown of PKC β. The relative expression levels of PKC α and β were measured (Figure 2b, right panel). Subsequently, the induction of apoptosis, after the suppression of PKC α, β or α plus β by the shRNAs, was tested using DNA fragmentation assay (Figure 2b, left panel). The knockdown of PKC α or β alone by each shRNA played no role in the induction of apoptosis in the cells with or without expressing v-Ha-ras. However, the concurrent knockdown of these two PKC isozymes caused about 50% of NIH3T3/Hras cells to undergo apoptosis. A similar result was obtained from Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection assay (Figure 2b, right panel). The shRNAs targeting other phorbol ester-dependent PKC ε, θ or η were also employed and none of them, alone or in various combinations, was able to sensitize the cells to apoptosis (data not shown). Thus, PKC α and β are the targets for the induction of apoptosis in NIH3T3/Hras cells.

Figure 2.

Concurrent knockdown of PKC α and β by the shRNAs triggers apoptosis in cells expressing v-ras. (a) After being infected with shRNA-PKC α, β, or scrambled shRNAs, NIH3T3 and NIH3T3/Hras cells were lysed and subjected to immunoblotting (left panels). The relative expression level of PKC α and β was measured and plotted (right panel). The error bars are SD of 3 independent experiments. (b) After being infected with shRNA-PKCα, β or the combination of both, NIH3T3 or NIH3T3/Hras cells were subjected to DNA fragmentation analysis (left panel). The percentage of the cells with sub-G1 DNA content was then plotted. Annexin V-FITC analysis was also performed after infecting cells with the shRNAs (right panel). The percentage of the cells stained positively with AnnexinV-FITC was plotted accordingly. The error bars are SD over 5 independent experiments (n = 5, *, p < 0.05). (c) Cell lysates were prepared from human prostate cancer HPV7 and PC3 cells, and analyzed for the phosphorylation of Akt at its ser473 and ser308 residues by immunoblotting. Even loading of proteins was normalized by Akt. (d) Expression of PKC α or β in HPV7 and PC3 cells, after infected with shRNA-PKC α, β or scrambled shRNAs, was analyzed by immunoblotting. The relative expression level of proteins was normalized by β-actin and presented as n-fold. (e) After co-knockdown of PKC α and β by the shRNAs, in the presence or absence of KP372-1 (0.1 μM), JNK inhibitor (5 μM) or PD98059 (5 μM), the prostate cancer cells were subjected to Annexin V-FITC analysis. The percentages of staining-positive cells were then plotted. The error bars are SD over 5 independent experiments (n = 5, *, p < 0.05). (f) Murine lung epithelial LA4 or cancer LKR cells infected with the shRNAs were subjected to Annexin V-FITC analysis. The percentages of staining-positive cells were plotted accordingly. The error bars are SD over 5 independent experiments (n = 5, *, p < 0.05).

It was reported that the treatment with GO6976 induced cells expressing v-ras or tumor cells harboring an active ras to apoptosis, in which Akt functioned as Ras downstream, apoptotic effector (Guo et al. 2009). To test whether Akt participated in apoptosis triggered by loss of PKC α and β, human prostate cancer PC3 cells that are known to contain the active form of Akt and HPV7 cells were used. The levels of Akt phosphorylated at Ser-308 ans 473 were examined using the anti-phophorylated Akt antibodies (Figure 2c). A high level of phosphorylated Akt at either Ser-308 or 473 was detected in PC3 cells. The active forms of Akt in HPV7 were at a very low level. The knockdown effect of PKC α or β by the shRNAs in these prostate cancer cells was then tested (Figure 2d). The shRNAs effectively blocked the expression of corresponding proteins, and did not show any off-target effect on the unrelated PKC isoforms. Annexin V apoptotic analysis was employed to test the effect of the concurrent knockdown of PKC α and β on the induction of apoptosis in these prostate cancer cells (Figure 2e). The co-inhibition of these two PKC isoforms had no apoptotic effect on HPV7 cells. On the contrary, the shRNAs triggered more than 25% of PC3 cells to undergo apoptosis and the addition of KP372 (an Akt inhibitor) blocked the induction of apoptosis. However, the addition of JNK inhibitor or PD98059 (a MAPK/ERK inhibitor) did not affect the magnitude of apoptosis, suggesting that Akt, but not JNK or MAPK, is involved in this apoptosis process elicited by concurrent knockdown of PKC α and β. Next, murine lung epithelial LA4 and cancer LKR cells harboring a mutated ras were tested for their susceptibility to apoptosis after co-knockdown PKC α and β (Figure 2f). Consistently, concurrent inhibition of these two PKC isoforms induced LKR cells (about 40%) to undergo apoptosis, and had no role in control LA4 cells. Overall, the data suggest that concurrent block of PKC α and β gene expression sensitizes cells with aberrant Ras signaling to apoptosis, in which Akt may be a key player.

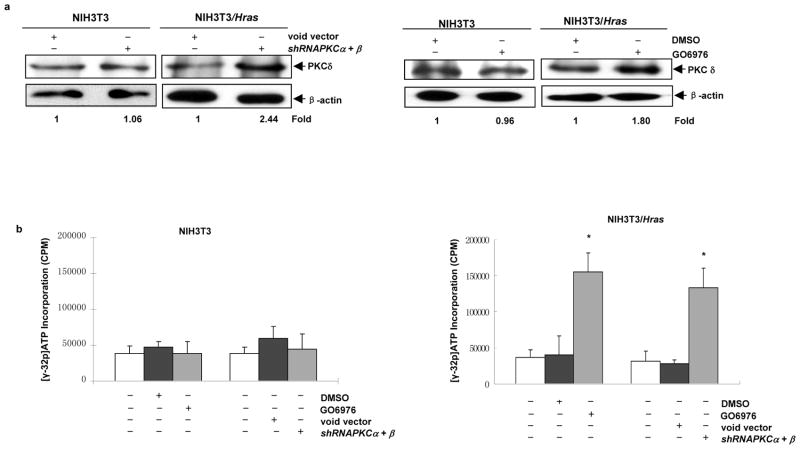

Activation of PKC δ in NIH/Hras cells after concurrent suppression of PKC α and β

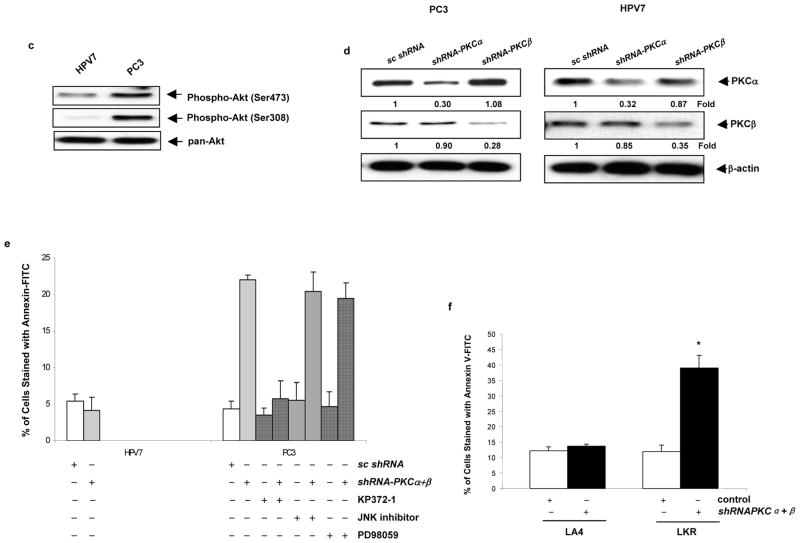

PKC δ often functions as a tumor suppressor by either inducing growth arrest or activating pro-apoptotic signals in many types of cells (Brodie et al., 2003; Gutcher et al., 2003). The suppression of this isoform was linked to apoptosis in cells expressing oncogenic ras (Xia et al., 2007). Here, we tested whether PKC δ played any roles in this apoptotic process. The expression of PKC δ in NIH3T3/Hras cells was examined by immunoblotting after concurrently knocking down PKC α and β by the shRNAs or GO6976 (Figure 3a). After co-suppressing PKC α and β, the level of PKC δ was upregulated in NIH3T3/Hras, but not in parental cells. The activity of PKC δ, following co-suppression of PKC α and β, was also measured (Figure 3b). After the cells were infected the shRNAs or treated with GO6976, cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-PKC δ antibody. The immunoprecipitates were then subjected to PKC activity analysis. Consistently, the co-inhibition of PKC α and β by genetic or chemical inhibitor augmented PKC δ activity (2–3 folds) in NIH3T3/Hras cells, but not parental NIH3T3 cells.

Figure 3.

Upregulation of PKC δ after the co-knockdown of PKC α and β. (a) With or without co-suppression of PKC α and β by the shRNAs or GO6976, lysates from NIH3T3 or NIH3T3/Hras cells were immunoblotted for PKC δ expression. The relative expression level of proteins was normalized by β-actin and presented as n-fold. (b) Lysates from untreated or treated cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-PKC δ antibody. The immunocomplexes were incubated with [32P] γ-ATP and the peptide substrates to determine PKC δ activity. The error bars represent SD from 3 independent experiments (n = 3, *, p < 0.05).

Nuclear translocation of PKC δ after the concurrent suppression of PKC α and β in the cells expressing v-ras

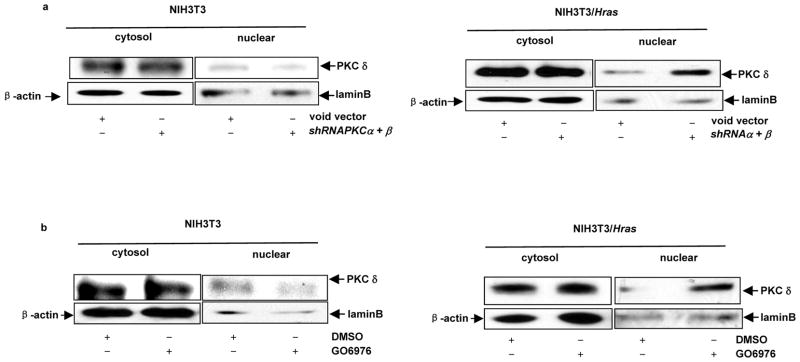

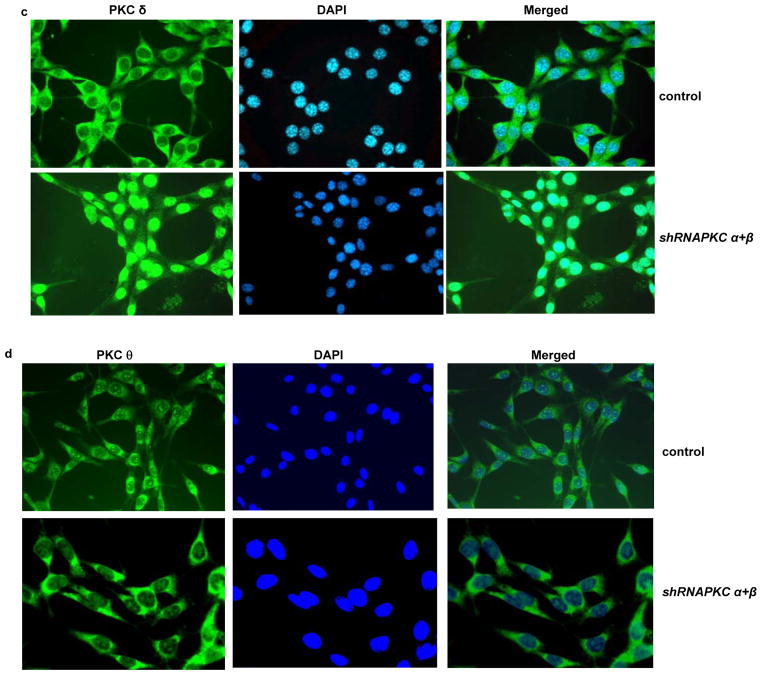

PKC δ possesses a NLS (nuclear localization sequence) domain (DeVries-Seimon et al., 2002). The nuclear translocation of PKC δ is important feature for this kinase to regulate apoptosis (DeVries-Seimon et al., 2007). The subcellular localization of this isozyme in our experimental setting was tested. After co-infected with shRNAPKC α and β (Figure 4a) or GO6976 treatment (Figure 4b), the cytosol and nuclear fractions were isolated from NIH3T3 and NIH3T3/Hras cells and immunoblotted with anti-PKC δ antibody. In NIH3T3 cells, a moderate amount of PKC δ was detected in the cytosol fractions with or without the treatments, and the protein was almost undetectable in the nuclear fractions. In contrast, a high amount of this isoform was present in the nuclear fractions of NIH3T3/Hras cells after co-suppression of PKC α and β or the treatment with GO6976. The data indicated that PKC δ was activated and translocated to the nucleus upon co-suppression of PKC α and β.

Figure 4.

Nuclear translocation of PKC δ following the concurrent suppression of PKC α and β in NIH3T3/Hras cells. (a and b) With or without suppression of PKC α plus β by the shRNAs (a) or GO6976 treatment (b), the cytosol or nuclear fraction was isolated from the cells and immunoblotted with anti-PKC δ antibody. β-actin and lamin B were used as loading controls for the cytosolic and nuclear fractions, respectively. (c–f) Immunofluorescent staining of PKC δ (c), θ (d), ε (e) or η (f) in NIH3T3/Hras cells co-infected with shRNA-PKC α plus β. After being incubated with the corresponding antibodies, respectively, the cells were stained with the second anti-mouse-IG antibody conjugated with fluorescein as well as with DAPI.

To further confirm the nuclear translocation of PKC δ, NIH3T3/Hras cells were co-infected with shRNA-PKCα plus β and then subjected to immunohistochemistry analysis using anti-PKCδ antibody as the primary antibody and goat anti-mouse IG antibody conjugated with fluorescein as the secondary antibody. The fluorescent staining was mainly seen in the cytosol of untreated cells. In contrast, after co-knockdown of PKC α and β, the fluorescein stained protein appeared in the nucleus, which was overlapped with DAPI stained nuclei. The similar phenomenon was obtained from the cells treated with GO6976 (data not shown). To further confirm that the nuclear translocation is specific to PKC δ, after being co-infected with shRNA-PKC α and β, NIH3T3/Hras cells were stained with anti-PKC θ (Figure 4d), ε (Figure 4e) and η (Figure 4f) antibodies, respectively and then the secondary fluorescein conjugated antibody. None of these PKC isoforms was detected in nucleus upon the knockdown of PKC α and β. These results further suggest the nuclear translocation of PKC δ in the cells expressing v-ras under the apoptotic condition.

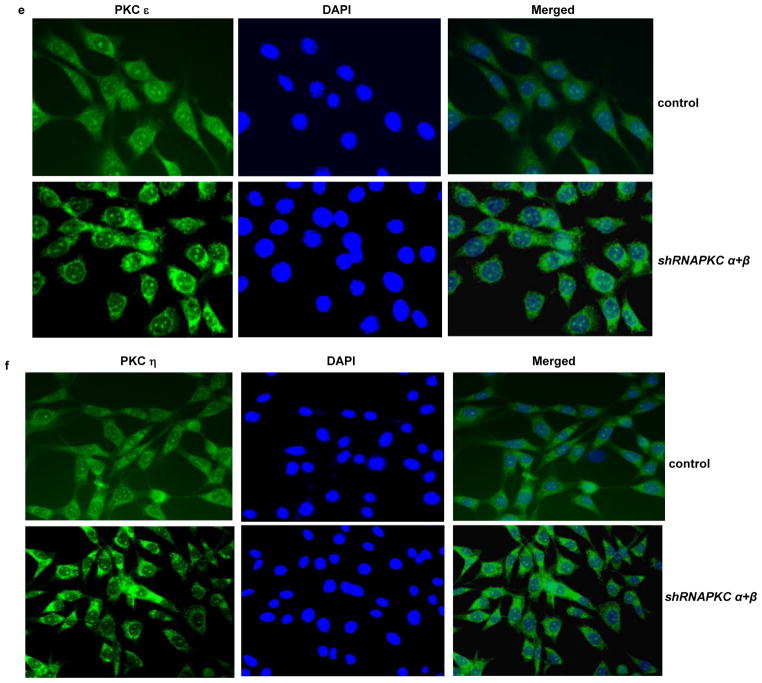

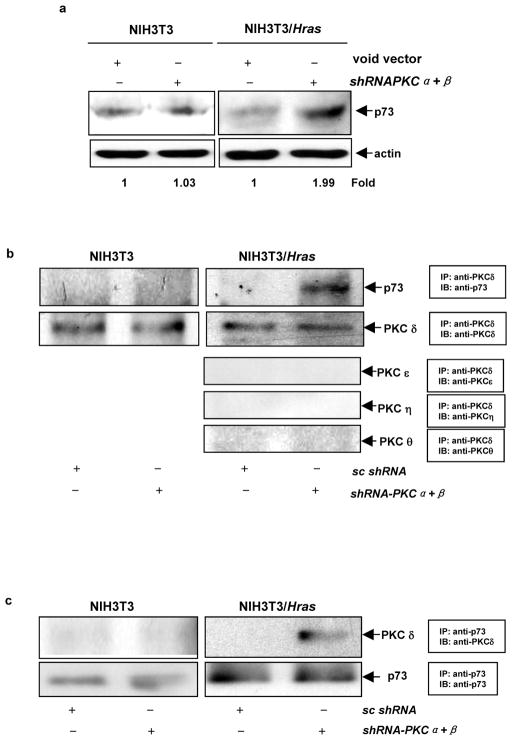

p73 is phosphorylated and interacted with PKC δ during the apoptotic process

p73 is a member of p53 tumor suppressor family and involved in the regulation of apoptosis upon genotoxic stress or after exposure to apoptotic stimuli (Whelan et al., 1998; Agami et al., 1999; Costanzo et al., 2002; Gong et al., 1999; Gonzalez et al., 2003; Irwin et al., 2003). Studies demonstrated that PKC δ could induce different types of cells to undergo apoptosis in response to DNA damage, in which p73 was activated (Ren et al., 2002; Reyland 2007). Since PKC δ is activated in our experimental setting, cell lysates from the cells with or without the co-knockdown of PKC α and β were prepared and the expression of p73 was analyzed by immunoblotting (Figure 5a). An increased amount of p73 was detected by the antibody in the lysate from NIH3T3/Hras cells after the co-infection of shRNA-PKC α and β, but not from parental cells. Subsequently, the nuclear association of PKC δ and p73 was analyzed. Immunoprecipitation in the nuclear fractions isolated from the cells with or without co-knocking down PKC α and β was performed using anti-PKC δ antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were then blotted with anti-p73 antibody (Figure 5b, first row). The association of p73 and PKC δ only occurred in the nucleus of NIH3T3/Hras cells after co-knockdown of PKC α and β, but not in that of parental cells. The equal amount of PKC δ in each immunoprecipitate was determined by immunoblotting the complexes with anti-PKC δ antibody (Figure 5b, second row). To exclude the existence of other PKC isoforms in the immunoprecipitates, the complexes pulled out by anti-PKC δ antibody were immunoblotted with anti-PKC ε, η or θ antibody, and none of these isoforms was being detected (Figure 5b, 3rd, 4th and 5th rows). The immunoprecipitation with anti-PKC ε, η or θ antibody and subsequent immunoblotting with anti-p73 antibody were also performed. There were no interactions between p73 and these isoforms with or without knockdown of PKC α and β (data not shown). Next, the reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were performed (Figure 5c). A similar result was obtained, in which the complexes precipitated with anti-p73 antibody from treated NIH3T3/Hrascells were recognized by anti-PKC δ antibody.

Figure 5.

Activation of p73 by PKC δ during the apoptotic process. (a) After being co-infected with shRNA-PKCα and β, NIH3T3 or NIH3T3/Hras cells was lysed and subjected to immunoblotting with anti-p73 antibody. The relative expression level of proteins was normalized by β-actin and presented as n-fold. (b) The nuclear fractions were isolated from the cells and subjected to co-immunoprecipitation using anti-PKC δ antibody. Subsequently, the immuno-complexes were blotted with anti-p73, -PKC ε, η or θ antibody, respectively. The input level of the immunoprecipitates was judged by probing the complexes with anti-PKC δ antibody (the second row). (c) The reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting of nuclear PKC δ and p73.

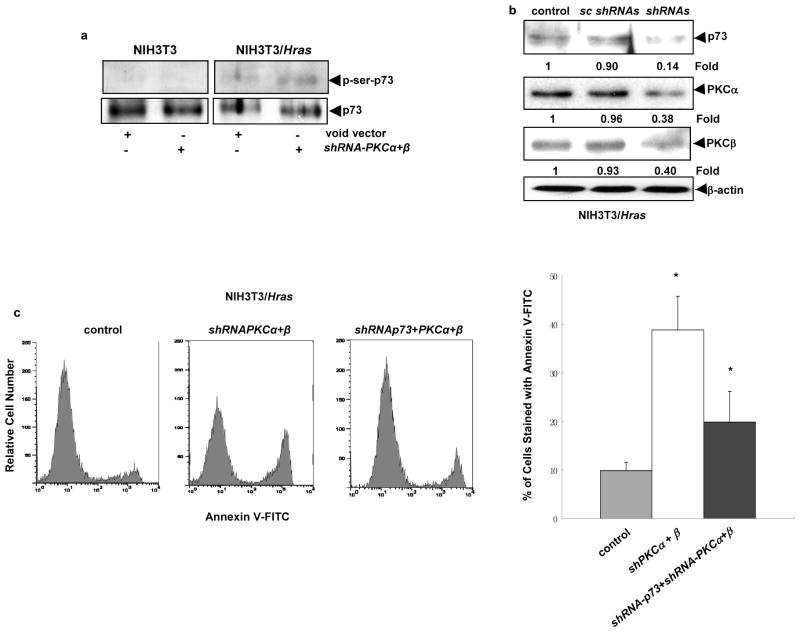

Activated PKC δ is implicated to phosphorylate p73 at serine/threonine residues during apoptosis (Ren et al., 2002; Gonzalez et al., 2003). Since PKC δ physically associated with p73 after the co-suppression of PKC α and β, we then tested whether p73 was phosphorylated under the apoptotic condition. After co-infected with shRNA-PKCα plus β, the cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-p73 antibody and then immunoblotting with the anti-phosphoserine antibody (Figure 6a). The phosphorylated p73 was detected only in NIH3T3/Hras cells after knockdown of PKC α and β, but not in parental cells. To further evaluate the necessity of p73 for the initiation of this apoptotic process, the shRNA targetting p73 was introduced into NIH3T3/Hras cells after concurrently suppressing PKC α and β. The effect of triple-knockdown of p73, PKC α and β was analyzed by immunoblotting (Figure 6b). The shRNAs sufficiently inhibited the expression of these molecules. Subsequently, the occurrence of apoptosis was assayed by Annexin V-FITC method (Figure 6c). The suppression of p73 partially blocked the apoptotic process in NIH3T3/Hras cells, indicating that p73 is a player in the induction of this cell death process. However, the incomplete suppression of the apoptotic process by shRNAp73 suggests the involvement of other apoptotic factors or the partial inhibition of p73, PKC α or β by the shRNAs.

Figure 6.

Nuclear p73 is phosphorylated and required for the induction of apoptosis. (a) The nuclear fractions from NIH3T3 and NIH3T3/Hras cells with or without co-knocking down PKC α and β were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-p73 antibody. The immuno-complexes were then subjected to immunoblotting with the anti-phospho-serine antibody. The input was judged by probing the same amount of immunoprecipitates with anti-p73 antibody. (b) After being infected with shRNAs (shRNA-PKC α, β plus p73) or sc shRNAs (mixed three scrambled shRNAs), NIH3T3/Hras cells were lysed and subjected to immunoblotting with corresponding antibodies. The relative expression level of proteins was normalized by β-actin and presented as n-fold. (c) After triple-infection, NIH3T3/Hras cells were subjected to Annexin V-FITC assay and the apoptotic cell population was plotted. Error bars represent SD from 5 independent experiments (n = 5, *, p < 0.05).

Cooperation among PKC isoforms for the induction of apoptosis

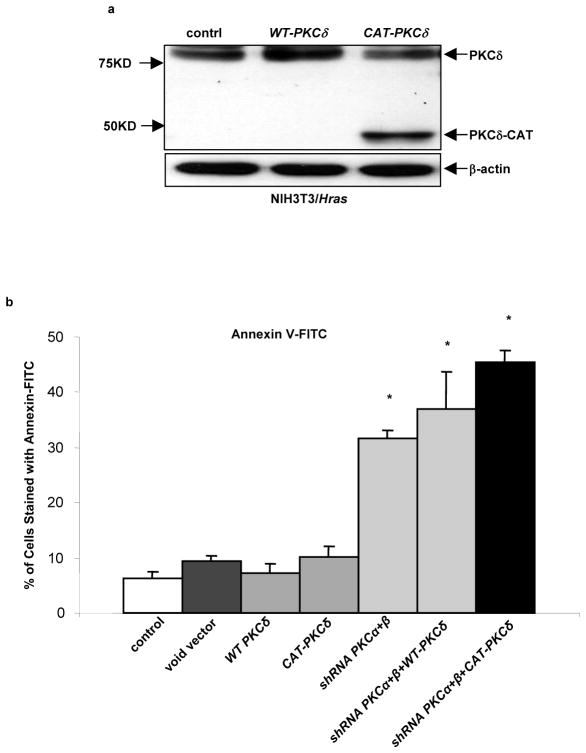

To further define the role of PKC δ in the induction of the apoptotic signaling transmitted by aberrant Ras, WT-PKCδ (wild-type PKC δ) or CAT-PKC δ (the constitutively-active form of PKC δ) was transiently transfected into NIH3T3/Hras cells, and the expression of exogenous WT-PKC δ and constitutively-active PKC δ was determined by immunoblotting (Figure 7a). Different forms of exogenous PKC δ were overexpressed in the cells. The occurrence of apoptosis with or without the concurrent knockdown of PKC α and β was then analyzed by Annexin V-FITC assay (Figure 7b). Interestingly, the overexpression of either wide-type or constitutively-active PKC δ alone was unable to induce apoptosis in NIH3T3/Hras cells. After co-inhibition of PKC α and β, the increased expression of PKC δ or the constitutively-active form of this isozyme not only induced apoptosis but also enhanced the magnitude of apoptosis in the cells. The same phenomenon was also observed in murine lung cancer LKR cells overexpressing WT-PKCδ or CAT-PKCδ (data not shown). Overall, the results suggest that the pro-apoptotic activity of PKC δ is elicited only when PKC α and β are concurrently suppressed.

Figure 7.

Concurrent suppression of PKC α and β is essential for the induction of PKC δ-mediated apoptosis. (a) After being transfected a wild-type PKCδ (WT-PKCδ) or constitutively-active PKC δ (CAT-PKCδ), NIH3T3/Hras cells were lysed and then subjected to immunoblotting with anti-PKC δ antibody. β-actin was used as a loading control. (b) After introduced PKC δ or CAT-PKC δ, NIH3T3/Hras cells, in the presence or absence of PKC α and β, were subjected to Annexin V-FITC analysis. The percentages of apoptotic cells were plotted. Error bars represent SD over 3 independent experiments (n = 3, *, p < 0.05).

Discussion

Study of Ras oncogene is a popular theme in the field of cancer research in light of the pivotal roles of Ras in the regulation of diverse cellular activities, such as proliferation, differentiation, senescence and apoptosis. In the process of tumorigenesis, it is critical for hyperactive Ras to maintain the balance in deregulated downstream effectors and to properly coordinate with other intracellular signals. Disruption of one or more of these signaling pathways would perturb homeostasis in cells harboring a mutated Ras and further trigger an apoptotic crisis. Recently, genome-wide RNA interference screens reveal that suppression of kinases involved in the regulation of cell growth is synthetic lethal with oncogenic K-ras (Scholl et al. 2009; Luo et al. 2009). Such synthetic lethal interaction also occurs between H- or K-Ras and loss of PKC (Chen et al., 1998a; Chen et al., 1998b; Xia et al., 2007). Since PKC family consists multiple isoforms, we in this investigation, using shRNAs, identified the isozymes critical for supporting the viability of cells expressing oncogenic ras. We demonstrated that after the concurrent suppression of PKC α and β, PKC δ in the cells expressing an aberrant Ras was upregulated and further translocated from the cytosol to the nucleus where it phosphorylated p73 for the induction of apoptosis. This PKC δ-mediated apoptotic signaling was activated only under the condition when PKC α and β were concurrently suppressed. Thus, our study not only indicates that mutated Ras, together with loss of PKC α and β, is apoptotic, but also suggests a potential balance among PKC isoforms in the regulation of the susceptibility of cells expressing v-ras to apoptosis.

Mutational activation of ras genes is a key event in human cancer development. During transformation process, cells develop secondary, adaptive mechanisms to coop with persistently increased Ras activity (Barbacid, 1987; Lowy et al., 1993; McComick et al., 1993). Survival of these cancer cells depend on factors that are downstream or parallel of Ras signaling pathway, or distal to Ras but functionally linked. Changes of the expression or activity of these factors would trigger a lethal consequence. The possibility of synthetic lethal interaction of oncogneic Ras with various cell growth regulators has been discussed (McNeill et al., 1999). The study, exclusively using rottlerin, demonstrated that the inhibition of PKC δ sensitizes various ras transformed cells (including NIH3T3 cells expressing v-Ha-ras) or tumor cells to apoptosis (Xia et al., 2007). In this process, Akt appeared to be crucial for the apoptotic action. It was also reported that the suppression of PKC α by the kinase dead mutant gene elicited PKC δ/ζ-dependent apoptosis in salivary epithelial cells, accompanied with JNK activation (Matassa et al. 2003). Previously, using ras loop mutant genes, we demonstrated that PI3K/Akt and JNK are involved in the induction of a full magnitude of apoptosis in response to PKC suppression (Guo et al. 2007). Here, using prostate cancer PC3 cells, it appears that after the co-knockdown of PKC α and β, Akt functions as one of Ras downstream, apoptotic effectors. The differential activations of Ras downstream effector pathways in each experimental setting may reflect the consequences of the different strategies used to suppress PKC or different types cells used.

PKC isoforms are serine/threonine protein kinases that are structurally distinct and functionally diverse. There is functional redundancy among PKC isozymes for restoring normal physiological status when one or more PKC isozymes are disabled. The functions of PKC isoforms have been shown to be rather controversial, which often depend on different cellular contexts or types of stimuli. For example, studies demonstrated that PKCα, β, δ, ε, ζ could either positively or negatively regulate tumorigenesis and apoptosis, indicating the functional complexity of PKC isozymes (Gutcher et al., 2003; Spitaler et al., 2004). Studies have also shown the interconnection between PKC and Ras signaling pathways (Kampfer et al., 2001; Rusanescu et al., 2001). Upon mitogenic stimulation, the SH2 binding sites of PKC are phosphorylated, which in turn recruit Grb2/SOS complex and activate Ras pathway in T lymphocytes (Kawakami et al., 2003). PKC is also indicated in the negative regulation of Ras signaling via modulating Ral activity (Rusanescu et al., 2001). The inhibition of PKC α was able to induce apoptosis through eliciting oxidative or ER stress in cells (Reylan et al., 2007). We previously showed that the suppression of PKC by GO6976 (a potential PKC α and β inhibitor) triggers apoptosis through Akt-mediated ER stress (Guo et al. 2009). GO6976 was shown to affect the activity of other types of serine/threonine kinases (for example, Chk1) (Aaltonen et al. 2007). The present study using shRNAs to specifically co-knockdown PKC α and β confirms the roles of these two PKC isoforms to induce cells expressing aberrant H-ras to undergo apoptosis, in which PKC δ is activated. It is conceivable that oncogenic H-Ras, through PI3K/Akt, influences PKC δ activity for the induction of apoptosis.

PKC α and PKC β have been traditionally referred to as promoting survival in different types of cells, such as endothelial, glioma, and epithelial cells (Whelan et al., 1998; Li et al., 1999; Deng et al., 2001), while PKC δ has been demonstrated to be a tumor suppressor (Emoto et al., 1995). Under certain circumstances (such as different types of cells), PKC δ was shown to promote cell proliferation (Jackson and Foster, 2004). Here, our study demonstrated that in cells expressing oncogenic ras, overexpression of wild-type or constitutively active PKC δ alone is not apoptotic. However, once concurrently knocking-down PKC α and β, the δ isozyme is upregulated, and becomes lethal for the cells. It is possible that a balance controlled by PKC α/β and δ copes with hyper-active Ras. Once the balance is disrupted, an apoptotic catastrophe occurs. Or, it is conceivable that cross-talks among PKC isoforms or with other intracellular signal transducers (such as Ras) exist in a hierarchic or parallel order within different subcellular compartments, which guide cells to achieve various biological outcomes.

PKC δ is activated by various apoptotic stimuli (such as ultraviolet (UV) radiation, γ-irradiation and genotoxic agents) in a variety of cell lines (for example, HeLa and HL60 cells) (Reylan et al., 2007). A direct regulation of the expression of PKC δ by activated Ras or PI3K under normal growth conditions was suggested (Xia et al. 2007). In salivary epithelial cells, the blockade of PKC α by a dominant-negative PKC α triggered PKC δ-dependent apoptosis, in which ERK was upregulated (Matassa et al. 2003). It was shown that in doxorubicin-induced apoptosis, JNK, through activating c-Jun and ATF2 transcription factors, is responsible for an increasing expression of PKC δ gene (Min et al., 2008). In our experimental setting, Akt appears to take part in the apoptotic process upon the co-suppression of PKC α and β. It is conceivable that Akt, as a downstream of oncogenic Ras, affects the activity of transcription factors and further PKC δ expression, the mechanisms of which is under way to be investigated.

p73 is a structural and functional homologue of p53, and participates in apoptosis initiated by DNA damage stimuli. Studies demonstrated that nuclear c-Abl was involved in p73-mediated apoptosis induced by genotoxic agents (Walworth et al., 1993; Agami et al., 1999). In this process, the nuclear c-Abl interacts with p73 and stimulates p73-regulated signaling. It is also known that in response to ionizing radiation or to cisplatin treatment, p73 functions as a key element in apoptotsis triggered by PKC δ (Ren et al., 2002). The present study shows that PKC δ translocated from the cytosol to the nucleus and activated p73 there during the apoptotic process. However, the inhibition of p73 partially blocked the process of cell death. Thus, our finding does not exclude the possibility that other factors, besides PKC δ, are involved in p73 activation in the current experimental setting. It is also likely that the partial suppression of apoptosis is due to incomplete suppression of p73.

Since more than 30% of human malignancies contain Ras mutations, targeting oncogenic Ras is viewed as an important strategy for development of new anti-cancer therapies. In this study, we show that the concurrent suppression of PKC α and β induces the cells ectopically expressing v-ras or cells with aberrant Akt signaling to undergo apoptosis, suggesting that hyperactive Ras and PI3K/Akt are essential players in this apoptotic pathway. Ras and PKC are important intracellular signal transducers for cell differentiation and proliferation. Dyregulation of Ras or PKC alone is compatible with cell viability. However, our current study suggests that aberrant Ras signaling, together with loss of PKC α plus β, severely perturb crucial survival signaling and further elicit an apoptotic crisis in the cell. With increasing attention in targeting Ras signaling for cancer treatment, our study provides the evidence for developing new therapeutic strategies to preferentially kill tumor cells harboring an active ras at clinically achievable doses, with effective indices that are higher than those of classic cytotoxic drugs.

Materials and methods

Cells and reagents

Murine fibroblasts NIH3T3, lung epithelial LA4 cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Murine lung cancer LKR cells that isolated from lung foci of v-ras transgenic mouse were obtained from Dr. Yu (Boston University). Human prostate cancer HPV7 and PC3 cells were provided by Dr. Luo (Boston University). These cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles’s medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated Fetal Bovine Serum (Atlanta Biologicals), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml Streptomycin (Invitrogen), except that LA4 cells were kept in Ham’s F12K medium supplemented with 15% Fetal Bovine Serum. GO6976, JNK inhibitor and PD98059 were purchased from EMD and KP372-1 was from Echelon Biosciences Inc. Antibodies against PKC α, β and Ras were purchased from BD, and those against PKC δ and p73 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The anti-Phosphotyrosine or anti-Phosphoserine antibodies were obtained from Millipore and Sigma, respectively. The antibodies against Akt or active Akt were purchased from Cell Signaling Inc.

The oligonucleotides containing small interference (si) RNA sequences targeting different Protein Kinase C isozymes were ligated to a lentiviral small-hairpin (sh) RNA expression vector pLentiLox3.7. The sequences of the siRNAs are: 5′-gaacgtgcatgaggtgaaa-3′ and 5′-tctgctgctttgttgtaca-3′ for murine PKC α and PKC β, 5′-ggctgtacttcgtcatgga-3′ and 5′-caggaagtcatcaggaata-3′ for human PKC α and PKC β. The siRNA sequence for p73 is as reported (Chau et al., 2004). The plasmids expressing wild type PKC δ (WT-PKCδ) and constitutively-active PKC δ (CAT-PKCδ) were generously gifted from Dr. J. Soh (Inha University, South Korea). v-Ha-ras was inserted into a retroviral MSCV vector (Clontech Laboratories). FuGene 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science) was used for transfections.

DNA fragmentation analysis

A flow cytometric analysis was performed using a FACScan (BD Biosciences). The data analysis was performed using the Cell-Fit software program (BD Biosciences). Cell-Fit receives data from the flow cytometer and provides real-time statistical analysis, computed at one second intervals, and also discriminates doublets or adjacent particles. Cells with sub-G0−G1 DNA contents after staining with propidium iodide were counted as apoptotic cells. In brief, following treatments, cells were harvested and then fixed in 70% cold ethanol. Afterwards, cells were stained with 0.1 mg/ml propidium iodide containing 1.5 mg/ml RNase. DNA contents of cells were then tested by a Becton Dickinson FACScan machine.

Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection assay

After treatments, cells were prepared and stained with Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Biosciences) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, the samples were analyzed by a flow cytometer.

Immunoblot and Ras activation analyses

Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose. After blocking with 5% non-fat milk for 1 hour at room temperature, the nitrocellulose was probed with antibodies and then visualized by chemilluminescence (Perkin-Elmer).

Active Ras Pull-Down and Detection kit (Thermo. Scientific, IL) was used. GTP bound Ras was then revealed by immunoblotting. Positive control was generated by treating lysate extracted from NIH3T3 cells with GTPγS to activate Ras.

Immunoprecipitation

After treatments, extracts were pre-cleared with unrelated antibodies from the same species and then incubated with anti- PKC δ or p73 antibody, followed by incubating with the protein A/G beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immunoprecipitates were washed 3 times with washing buffer (0.1% NP-40, 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF and 1 mM NaV3O4, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate) and then eluted in sample buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH6.8, 2% SDS, 6% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% bromophenol blue and 10% glycerol) for immunoblotting analysis.

Subcellular fractions preparation

For whole cell lysates, cells were lysed with 1% NP-40 lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF and 1 mM NaV3O4) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) on ice for 30 min. After centrifugation, supernatants were collected as cell lysates. The nuclear and cytosol fractions were isolated using the nuclear/cytosol fractionation kit from BioVision (BioVision, CA), or by following procedure. Briefly, cells were incubated with 1% Triton X-114 lysis buffer (1% Triton X-114, 25 mM Tris, pH7.5, 20 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 1 μg/mL aprotinin and 1 μg/mL leupeptin) on ice for 30 min and then homogenized by passing through a 25-gauge needle for 45 passages. After centrifuging at 280 g for 15 min, supernantant was collected as the cytosol fraction. The precipitated nuclei were then lysed with nuclear lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH7.6, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/ml aprotinin and 1 μg/ml leupeptin) on ice for 10 min. The nuclear extract was collected by re-centrifuging at 280 g for 15 min.

Immunofluorescence

After treatments, cells seeded on coverglass were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde in 1 × PBS (phosphate buffered saline) for 10 min. Following permeabilization with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min at room temperature, cells were incubated with anti-PKC δ primary antibody and then incubated with a FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Invitrogen) as well as DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). The cells were visualized with Zeiss Axio Imager Z microscope. The images were captured using the AxioVision Rel. 4.6 software (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging).

In vitro protein kinase C activity assay

A PKC activity assay kit (Millipore) was used. Briefly, PKC δ was isolated with the antibody and incubated with PKC substrate peptide, [γ-32P] ATP, PKA/CaMK inhibitors as well as PKC lipid activator for 10 min at 30°C. The 32P- incorporated substrates were then bound to P81 filter paper, washed and quantitated by a scintillation counter.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Z. Luo and Q. Yu (Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA) for providing various reagents and useful suggestions. This study is supported by NIH (RO1CA100498) and DOD (W81XWH-04-1-0246).

References

- Aaltonen V, Koivunen J, Laato M, Peltonen J. PKC inhibitor GO6976 induces mitosis and enhances doxorubicin-paclitaxel cytotoxicity in urinary bladder carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2007;253:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agami R, Blandino G, Oren M, Shaul Y. Interaction of c-Abl and p73 and their collaboration to induce apoptosis. Nature. 1999;399:809–813. doi: 10.1038/21697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atten MJ, Godoy-Romero E, Attar BM, Milson T, Zopel M, Holian O. Resveratrol regulates cellular PKCα and δ to inhibit growth and induce apoptosis in gastric cancer cells. Invest New Drugs. 2005;23:111–119. doi: 10.1007/s10637-005-5855-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbacid M. Ras genes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:779–827. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.004023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun MU, Mochly-Rosen D. Opposing effects of delta- and zeta-protein kinase C isozymes on cardiac fibroblast proliferation: use of isozyme-selective inhibitors. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:895–903. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie C, Blumberg PM. Regulation of cell apoptosis by protein kinase c delta. Apoptosis. 2003;8:19–27. doi: 10.1023/a:1021640817208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chau BN, Chen TT, Wan YY, Degregori J, Wang JY. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis requires p73 and c-ABL activation downstream of RB degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4438–4447. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4438-4447.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Liou J, Forman LW, Faller DV. Correlation of genetic instability and apoptosis in the presence of oncogenic Kiras. Cell Death Differ. 1998a;5:984–995. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Liou J, Forman LW, Faller DV. Differential regulation of discrete apoptotic pathways by Ras. J Biol Chem. 1998b;273:16700–16709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Juo P, Liou J, Li CQ, Yu Q, Blenis J, Faller DV. The recruitment of Fas-associated death domain/caspase 8 in Ras-induced apoptosis. Cell Growth Differe. 2001;12:297–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo A, Merto P, Pediconi N, Fulco M, Sartorelli V, Cole PA, et al. DNA damage-dependent acetylation of p73 dictates the selective activation of apoptotic target genes. Mol Cell. 2002;9:175–186. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00431-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Kornblau SM, Ruvolo PP, May WS. Regulation of Bcl2 phosphorylation and potential significance for leukemic cell chemoresistance. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 2001;28:30–37. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denning MF, Dlugosz AA, Threadgill DW, Magnuson T, Yuspa SH. Activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor signal transduction pathway stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation of protein kinase C delta. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5325–5331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries-Seimon TA, Neville MC, Reyland ME. Nuclear import of PKCδ is required for apoptosis: identification of a novel nuclear import sequence. EMBO J. 2002;21:6050–6060. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries-Seimon TA, Ohm AM, Humphries MJ, Reyland ME. Induction of Apoptosis is driven by nuclear retention of protein kinase Cδ. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22307–22314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703661200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitel K, Staiger H, Rieger J, Mischak H, Brandhorst H, Brendel MD, et al. Protein kinase Cδ activation and translocation to the nucleus are requited for fatty acid-induced apoptosis of insulin-secreting cells. Diabetes. 2003;52:991–997. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.4.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emoto Y, Manome Y, Meinhardt G, Kisaki H, Kharbanda S, Roberson M, et al. Proteolytic activation of protein kinase C delta by an ICE-like protease in apoptotic cells. EMBO J. 1995;14:6148–6156. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emoto Y, Ksaki H, Manome Y, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. Activation of protein kinase Cdelta in human myeloid leukemia cells treated with 1-beta-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine. Blood. 1996;87:1990–1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukasawa K, Rulong S, Resau J, Pinto da Silva P, Woode GF. Overexpression of mos oncogene product in Swiss3T3 cells induces apoptosis preferentially during S-phase. Oncogene. 1995;10:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghayur T, Hugunin M, Talanian RV, Ratnofsky S, Quinlan C, Emoto Y, et al. Proteolytic activation of protein kinase C delta by an ICE/CED 3-like protease induces characteristics of apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2399–2404. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong JG, Costanzo A, Yang HQ, Melino G, Kaelin WG, Jr, Levrero M, et al. The tyrosine kinase C-Abl regulates p73 in apoptotic response to cisplatin-induced DNA damage. Nature. 1999;399:806–809. doi: 10.1038/21690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez S, Prives C, Cordon-Cardo C. p73α regulation by Chk1 in response to DNA damage. Mol Cel Bi. 2003;23:8161–8171. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8161-8171.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Guo J, Zhu T, Luo LY, Huang Y, Sunkavalli RG, Chen CY. PI3K acts in synergy with loss of PKC to elicit apoptosis via the UPR. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107:76–85. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutcher I, Webb PR, Anderson NG. The isoform specific regulation of apoptosis by protein kinase C. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:1061–1070. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2281-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries MJ, Limesand KH, Schneider JC, Nakayama KI, Anderson SM, et al. Suppression of apoptosis in the protein kinase C delta null mouse in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9728–9737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M, Kondon K, Marin MC, Cheng LS, Hahn WC, Kaelin WH., Jr Chemosensitivity linked to p73 function. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:403–410. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DN, Foster DA. The enigmatic protein kinase Cδ: Complex roles in cell proliferation and survival. FASEB J. 2004;18:627–636. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0979rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost CA, Marin MC, Kaelin WG. p73 is a human p53-related protein that can induce apoptosis. Nature. 1997;389:191–194. doi: 10.1038/38298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajimoto T, Shirai Y, Sakai N, Yamamoto T, Matsuzaki H, Kikkawa U, et al. Ceramide-induced apoptosis by translocation, phosphorylation and activation of protein kinase Cδ in the Golgi complex. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12668–12676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312350200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampfer S, Windegger M, Hochholdinger F, Schwaiger W, Pestell RG, Baier G, et al. Protein kinase C isoforms involved in the transcriptional activation of cyclin D1 by transforming Ha-ras. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42834–42842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102047200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul S, Anantharam V, Yang Y, Choi CJ, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG. Tyrosine phosphorylation regulates the proteolytic activation of protein kinase Cδ in dopaminergic neuronal cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28721–28730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami Y, Kitaura J, Yao L, McHenry RW, Kawakami Y, Newtori AC, et al. A ras activation pathway dependent on syk phosphorylation of protein kinase C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9470–9475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633695100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheifets V, Bright R, Inagaki K, Schechtman D, Mochly-Rosen D. Protein kinase Cδ (δPKC)-Annexin V interaction: a required step in δPKC translocation and function. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23218–23226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602075200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiley SC, Clark KJ, Duddy SK, Welch DR, Jaken S. Increased protein kinase C delta in mammary tumor cells: relationship to transformtion and metastatic progression. Oncogene. 1999;18:6748–6757. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine AJ. p53 the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell. 1997;88:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Jiang YX, Zhang J, Soon L, Flechner L, Kapoor V, Pierce JH, Wang LH. Protein kinase C-delta is an important signaling molecule in insulin-like growth factor I receptor-mediated cell transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5888–5898. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Emanuele MJ, Li D, Creighton CJ, Schlabach MR, Westbrook TF, Wong K-K, Elledge SJ. A genome-wide RNAi screen identifies multiple synthetic lethal interactions with the Ras oncogene. Cell. 2009;137:835–848. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowy DR, Willumsen BM. Function and regulation of Ras. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:851–891. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.004223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandil R, Ashkenazi E, Blass M, Kronfeld I, Kazimirsky G, Rosenthal G, et al. Protein kinase Calpha and protein kinase Cdelta play opposite roles in the proliferation and apoptosis of glioma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4612–4619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matassa A, Carpenter L, Biden T, Humphries M, Reyland M. PKCdelta is required for mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis in salivary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29719–29728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick F. Signal transduction: how receptors turn Ras on. Nature. 1993;363:5–16. doi: 10.1038/363015a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill H, Downward J. Apoptosis: Ras to the rescue in the fly eye. Curr Biol. 1999;9:176–179. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min BW, Kim CG, Ko J, Lim Y, Lee YH, Shin SY. Transcription of the protein kinase C-δ gene is activated by JNK through c-Jun and ATF2 in response to the anticancer agent doxorubicin. Exp and Mole Medicine. 2008;40:699–708. doi: 10.3858/emm.2008.40.6.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno K, Noda K, Araki T, Imagoka T, Kobayashi Y, Akita Y, et al. The proteolytic cleavage of protein kinase C isotypes, which generates kinase and regulatory fragments, correlates with Fas-mediated and 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate-induced apoptosis. Eur J Biochem. 1997;250:7–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murriel CL, Churchill E, Inagaki K, Szweda LI, Mochly-Rosen D. Protein kinase Cdelta activation induces apoptosis in response to cardiac ischemia and reperfusion damage: a mechanism involving BAD and the mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47985–47991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405071200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni H, Ergin M, Tibudan SS, Denning MF, Izban KF, Alkan S. Protein kinase C-delta is commonly expressed in multiple myeloma cells and its downregulation by rottlerin causes apoptosis. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:849–856. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka Y. Protein kinase C and lipid signaling for sustained cellular responses. FASEB J. 1995;9:484–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J, Datta R, Shioya H, Li Y, Oki E, Biedermann V, et al. p73β is regulated by protein kinase Cδ catalytic fragment generated in the apoptotic response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33758–33765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110667200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyland M, Anderson S, Matassa A, Barzen K, Quissell D. Protein kinase C delta is essential for etoposide-induced apoptosis in salivary gland acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19115–19123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyland ME. Protein kianse C delta and apoptosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1001–1004. doi: 10.1042/BST0351001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusanescu G, Gotoh T, Tian X, Feig L. Regulation of Ras signaling specificity by protein kinase C. Mol Chem Biol. 2001;21:2650–2658. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2650-2658.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl C, Frohling S, Dunn IF, Schinzel AC, Barbie DA, Kim SY, Silver SJ, Tamayo P, Waldlow RC, Ramaswamy S, Dohner K, Bullinger L, Sandy P, Boehm JS, Root DE, Jacks Y, Hahn WC, Gilliland G. Sythetic lethal interaction between oncogenic KRAS dependency and STK33 suppression in human cancer cells. Cell. 2009;137:821–834. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitailo LA, Tibudan SS, Denning MF. Bax activation and induction of apoptosis in human keratinocytes by the protein kinase C delta catalytic domain. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:434–443. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitaler M, Cantrell DA. Protein kinase C and beyond. Nature Immunol. 2004;5:785–790. doi: 10.1038/ni1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walworth N, Davey S, Beach D. Fission yeast chk1 protein kinase links the rad checkpoint pathway to cdc2. Nature. 1993;363:368–371. doi: 10.1038/363368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HG, Reed JC. Bcl-2, Raf-1 and mitochondrial regulation of apoptosis. Biofactors. 1998;8:13–16. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520080103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan AD, Parker PJ. Loss of protein kinase C function induces an apoptotic response. Oncogene. 1998;16:1939–1944. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia S, Forman LW, Faller DV. Protein kinase Cδ is required for survival of cells expressing activated p21RAS. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13199–13210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610225200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A, Kaghad M, Caput D, McKeon F. On the shoulders of giants: p63, p73 and the rise of p53. Trends Genet. 2002;18:90–95. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02595-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XM, Chen J, Xia YG, Xu Q. Apoptosis of murine melanoma B16-BL6 cells induced by queretin targeting motochondria, inhibiting expression of PKCα and translocating PKCδ. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;55:251–262. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0863-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]