Abstract

Background

Gene duplications are a molecular mechanism potentially mediating generation of functional novelty. However, the probabilities of maintenance and functional divergence of duplicated genes are shaped by selective pressures acting on gene copies immediately after the duplication event. The ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous substitution rates in protein-coding sequences provides a means to investigate selective pressures based on genic sequences. Three molecular signatures can reveal early stages of functional divergence between gene copies: change in the level of purifying selection between paralogous genes, occurrence of positive selection, and transient relaxed purifying selection following gene duplication. We studied three pairs of genes that are known to be involved in an interaction with symbiotic bacteria and were recently duplicated in the history of the Medicago genus (Fabaceae). We sequenced two pairs of polygalacturonase genes (Pg11-Pg3 and Pg11a-Pg11c) and one pair of auxine transporter-like genes (Lax2-Lax4) in 17 species belonging to the Medicago genus, and sought for molecular signatures of differentiation between copies.

Results

Selective histories revealed by these three signatures of molecular differentiation were found to be markedly different between each pair of paralogs. We found sites under positive selection in the Pg11 paralogs while Pg3 has mainly evolved under purifying selection. The most recent paralogs examined Pg11a and Pg11c, are both undergoing positive selection and might be acquiring new functions. Lax2 and Lax4 paralogs are both under strong purifying selection, but still underwent a temporary relaxation of purifying selection immediately after duplication.

Conclusions

This study illustrates the variety of selective pressures undergone by duplicated genes and the effect of age of the duplication. We found that relaxation of selective constraints immediately after duplication might promote adaptive divergence.

Keywords: Duplication, Medicago, Neofunctionalization, Subfunctionalization, Paralogs evolution

Background

Gene duplications have long been hypothesized to be drivers of genome and gene function evolution [1]. Recently, availability of large-scale sequence data, and especially entire genome sequences, has brought significant support to this view [2,3]. In plants, duplications appear to be frequent and most lineages studied up to now have been affected by whole-genome duplication events (polyploidy) and/or segmental duplications [4-10].

Starting with Ohno, a range of models has been proposed to predict the fates of paralogous gene pairs resulting from duplications. These models can be categorized by their assumptions: they can be either neutral or involving natural selection, and can consider the early stage of duplication, i.e. when the duplication is not yet fixed in the species or start with the assumption that the gene duplication has just been fixed (recently reviewed in [11]).

Immediately after the gene duplication event, the two copies are assumed to be identical and therefore functionally redundant. At this stage, there should be no selective pressure against any loss-of-function mutation affecting either copy. As a result, it is believed that most instances of gene duplications will eventually result in the loss of one of the copies (pseudogenization or nonfunctionalization). However, the relaxation of purifying selection (due to the initial redundancy) may allow some amount of divergence and occasionally can let one copy acquire a new function and be subsequently maintained by natural selection (neofunctionalization). This scenario is essential for the creative role of duplication envisioned by Ohno [1]. Force et al.[12] suggested that the presence of two redundant genes may drive the fixation of complementary degenerative mutations in both of copies, with higher probability in gene regulatory regions. At the end of this process, both gene copies are required to perform the set of functions originally performed by a single gene (subfunctionalization). These two scenarios are not mutually exclusive and may act jointly [13]. Besides these models, the maintenance of functionally redundant copies (without functional divergence) could be adaptive under specific circumstances, either through dosage effect or as a means of genetic robustness against deleterious mutations [14-16] and therefore also explain the fixation of duplications in species [11].

Functional analyses have been performed in order to determine the relative importance or the interaction between these different models. The occurrence and the characteristics of functional divergence of paralogous genes can be addressed either through the regulatory or protein-coding sequence angle.

Whole-genome expression profiles revealed divergent expression patterns between paralogous gene pairs, providing indirect evidence for subfonctionalization and/or neofunctionalization [17]. Similar conclusions were also drawn from studies of polyploid species for which duplicated genes were instantly fixed in the species founder individual [18-20]. More specific and detailed functional analyses revealed several cases of paralogs undergoing neofunctionalization or subfunctionalization [21,22].

Beside differences in gene expression, rates of molecular evolution can be used to qualify the constraints experienced by genes. In particular, contrasting the rate of protein-changing (non-synonymous) substitution (dN) and the rate of silent (synonymous) substitution (dS) at the nucleotide level allows qualifying the type of selection acting on individual gene copies after a duplication event. The intensity of purifying selection is often estimated through the ratio ω = dN/dS. Values of ω < 1 are interpreted as evidence for purifying selection (the lower ω, the stronger purifying selection). Following pseudogenization, ω = 1 is expected (no constraint). Last, amino acid sites exhibiting ω > 1 are likely directly targeted by positive selection. As an example, the evolutionary fate of ten genes recently duplicated by retrotransposition in mice was studied by contrasting synonymous and non-synonymous rates [23]. Gene duplications have been the subject of many functional and molecular studies in plants [24,25], but here we aimed at analysing specifically the selective constraints exerted on duplicated genes through analysis of their rates of substitution. In order to shed light to the temporal variation of selective constraints acting on duplicated genes following their duplication, we focused on the evolution of fairly recent duplicated genes at a time scale appropriate for coding sequence evolution rates analysis. Such study can provide insight about the relative role of relaxation of purifying selection and positive selection in the fate of duplicated genes.

We investigated rates of molecular evolution of three duplicated gene pairs in the genus Medicago (L.), therefore maximizing the amount of available phylogenetic signal. We selected gene pairs involved directly or indirectly in the symbiotic interaction between legumes and nitrogen-fixing bacteria (rhizobia). The first genes code for polygalacturonases, which are enzymes involved in the degradation of polysaccharides. One member (Pg11) is involved in pollen tube elongation and the other (Pg3) in the tip growth of the infection threads during the establishment of the symbiosis with nitrogen-fixing bacteria Sinorhizobium sp [26]. The second genes are Lax (Like-Aux1). They are auxin efflux carriers and play an important role in auxin-controlled processes such as tissue growth and in particular development of nodules.

Mutualistic host-symbiont interactions present the interest of combining several features we can expect will promot fast evolution. Mutualisms are often based on nutrient exchanges and involve strong selective pressures, since both costs and benefits are important. The interaction with a biotic partner can cause shifting selective optima, especially if there are conflicts of interest. Finally, in contrast with host-pathogen interactions, mutualisms can involve the evolution of novel structures by both partners. The legume-rhizobium symbiosis evolved relatively recently, around 60 million years ago, culminating with the emergence of a specific organ, the root nodule [27]. Therefore, the genes underlying rhizobial symbiosis in legumes are likely to record the signatures of past selective pressures caused by the emergence and diversification of symbiosis as well as pressures linked to their current function. Due to a whole-genome duplication event that occurred approximately 58 Myr ago [28], legumes are therefore a good model to examine the changes of selective pressures over time for duplicated genes.

Rates of molecular evolution of paralogous gene copies (hereafter paralogs) should be studied preferably in a variety of species to have enough power to inner substitution rates. Moreover paralogs should be characterized in a set of extant species that have diverged after the ancestral gene duplication. In spite the growing availability of full genome sequences, plant model species are usually not related enough to allow for analysis of divergence at the nucleotide level. In the case of the Fabaceae family, three species have been sequence (Medicago truncatula, Lotus japonicus and Glycine max), but their divergence times would represent a time scale of 50–60 million years [29]. Moreover, more taxa are needed for contrasting early and late selective pressures. We re-sequenced three pairs of relatively recently duplicated genes in 16 other species of the Medicago genus (in addition to M. truncatula). We chose duplicated genes that (i) are recent enough so that the signatures of evolution post-duplication are still detectable, (ii) predate the speciation events within the Medicago genus, so that each copy is found within all species and (iii) contain at least one gene demonstrated or strongly suspected to be involved in the legume-specific symbiotic interaction with nitrogen-fixing rhizobium bacteria.

Results

Sequencing Pg11a, Pg11c, Lax2 and Lax4

Depending of the gene, a successful amplification was obtained for a total of 10 to 17 species. The resulting sequence alignments had a length of 729 bp for Pg genes and 798 bp for Lax genes. We excluded sequences that did not encode a complete protein (due to frame shift or nonsense mutations) because they might represent pseudogenes and affect our estimates of rates of molecular evolution in functional paralogs. Accession numbers of sequences deposited in GenBank are from JN635641 to JN635687. Already available sequences GenBank accession numbers are AJ620946, AY115843 and AY115844 (for M. truncatula genes Pg3, Lax2 and Lax4 respectively), HQ737838, HQ736585 and HQ736701 (for M. tornata genes Pg3, Lax2 and Lax4 respectively). Details about the sequences obtained as well as GenBank accession numbers are given in Additional file 1.

Phylogeny of Pg and Lax genes

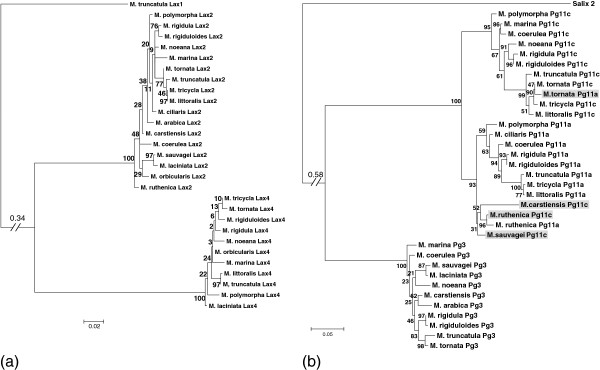

The phylogeny of Lax and Pg paralogs were reconstructed using maximum likelihood and are presented in Figure 1a and Figure 1b respectively. The topologies obtained for the three paralog pairs Lax2/Lax4, Pg3/Pg11 and Pg11a/Pg11c confirmed the occurrence of three duplication events predating the divergence between the 17 species we included from the Medicago genus. Moreover, the branches leading to each paralog clade containing the sequences of the same gene amplified from different species are well supported. Bootstrap values for the branches leading to the Lax2, Lax4, Pg3 and Pg11 clades are equal to 100. Within the Pg11 clade, bootstrap values obtained for the branches leading to the Pg11a and Pg11c clades are 95 and 93 respectively. However, within the Pg11a and Pg11c clades, several inconsistencies were observed in the phylogenies: sequences obtained with the Pg11c copy specific primers for M. carstiensis, M. ruthenica and M sauvagei were placed in the Pg11a clade, and conversely, sequences obtained with the Pg11a copy specific primers for M. tornata were placed in the Pg11c clade (highlighted in grey in Figure 1b). There are several explanations for such inconsistencies: erroneous amplification (for example chimeric amplification), the amplification of a third copy resulting from an independent duplication, or genic conversion between paralogs. In order to avoid erroneous interpretations, we did not consider these four sequences further in our analysis.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic trees for Lax and Pg genes. Phylogenetic trees obtained for Lax2 and Lax4 (a) and for Pg3, Pg11a and Pg11c genes (b). Bootstrap values (% of 100 re-sampled data set) are indicated for each branch. For presentation convenience, the branch leading to the outgroup was shortened (as indicated by an inclined double segment). Sequences underlined in light grey represent instances were a paralog is placed in the wrong clade when considering the copy specific primers used for its amplification.

The species phylogeny deduced from the data was not completely congruent between different paralogs and with the species phylogeny described in the literature [30,31]. However, within clades regrouping sequences of a same gene in the different species, branches are not well supported (Figure 1), indicating a poor phylogenetic resolution. Only three groups of species were grouped with high support, irrespective of the gene analysed. The first includes M. tornata, M. truncatula, M. tricycla and M. littoralis, the second M. rigidula and M. rigiduloïdes and the third M. sauvagei and M. laciniata. The Medicago genus evolved through a large number of speciation events in a short time span, and as a result, the resolution of phylogenetic relationships between Medicago species is difficult. Furthermore, incongruences may be observed between gene and species trees due to incomplete lineage sorting [32]. For each paralog set, we used the best fitting phylogenetic tree. We repeated the analyses of selective constraints for each gene pair using either the best topology found for the genes considered or a tree topology from the literature [30]. Results were very similar and conclusions were not affected. Consequently, only results obtained using the phylogeny from our data are presented.

Analysis of selective pressures along trees: testing for an “age” and a “paralog” effect

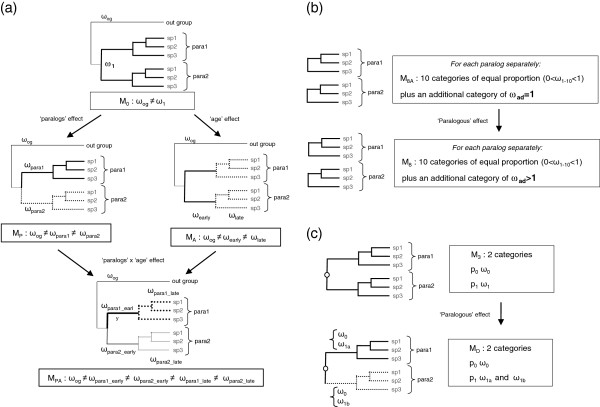

Comparing models with different constraints on the value of ω among branches of the tree allows testing evolutionary hypotheses (Figure 2a). The comparisons of MA versus M0 and MPA versus MP test the “age effect” by contrasting early branches (when the duplication was young) and later branches. Similarly, the comparisons of MP versus M0 and MPA versus MA test a “paralog effect” by examining the divergence between the two copies. Results of these tests are presented in Table 1 along with maximum-likelihood estimates of ω parameters of each model. When the Pg11/Pg3 paralogs pair was analysed, both the sequences of Pg11a and Pg11c were considered for Pg11. For example, for testing the MP model, both branches leading to Pg11a and Pg11c were considered for Pg11. For testing the MA model, the branch between the node corresponding to the duplication between Pg11 and Pg3 and the node corresponding to the duplication between Pg11a and Pg11c (i.e. the ancestral Pg11 gene) was considered as the late branch. Thus, any effects related to the duplication between Pg11a and Pg11c is considered only in the Pg11a/Pg11c paralogs pair analysis.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the codon models used. (a) Models allowing dN/dS variation along lineages. Arrows indicate the questions addressed by the comparison between models (in (a), the arrows correspond to hierachical relationships). (b) Models allowing dN/dS variation along the gene. In M8A, ω follows a β distribution discretized into 10 categories of similar frequency (0 < ω1–10 < 1) and an additional category of ω is fixed at 1 (ωad = 1, accounting for neutral sites); M8 differs from M8A only by the additional category of ω which is constraint to be superior to 1 (ωad > 1), to account for sites under positive selection. (c) Phylogenetic trees harbours two clades, one for each paralog (the outgroup is not represented here). Models are either specifying identical categories of dN/dS in both clades (M3), or allowing one category to take a different value in each clade (MD).

Table 1.

Branch models: estimated parameters and log-likelihood ratio tests

| Paralog pair | Model | logL | np | Branchs | ω | LRT | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

M0 |

−2847.12 |

58 |

OG |

0.05 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Lax |

0.08 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

OG |

0.05 |

|

|

|

| |

MP |

−2846.50 |

59 |

Lax2 |

0.07 |

vs. M0 |

1.24 |

0.26 |

| |

|

|

|

Lax4 |

0.10 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

OG |

0.05 |

|

|

|

| Lax2/Lax4 |

MA |

−2840.62 |

59 |

Laxearly |

0.14 |

vs. M0 |

13.0** |

0.00031 |

| |

|

|

|

Laxlate |

0.05 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

OG |

0.05 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Lax2early |

0.19 |

vs. MP |

13.8** |

0.001 |

| |

MPA |

−2839.60 |

61 |

Lax4early |

0.11 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Lax2late |

0.04 |

vs. MA |

2.04 |

0.36 |

| |

|

|

|

Lax4late |

0.06 |

|

|

|

| |

M0 |

−4127.20 |

62 |

OG |

0.06 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Pg |

0.33 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

OG |

0.06 |

|

|

|

| |

MP |

−4125.06 |

63 |

Pg3 |

0.25 |

vs. M0 |

4.28* |

0.04 |

| |

|

|

|

Pg11 |

0.41 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

OG |

0.06 |

|

|

|

| Pg3/Pg11 |

MA |

−4124.78 |

63 |

Pgearly |

0.22 |

vs. M0 |

4.84* |

0.03 |

| |

|

|

|

Pglate |

0.38 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

OG |

0.06 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Pg3early |

0.24 |

vs. MP |

3.68 |

0.16 |

| |

MPA |

−4123.22 |

65 |

Pg11early |

0.21 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Pg3late |

0.29 |

vs. MA |

3.12 |

0.21 |

| |

|

|

|

Pg11late |

0.44 |

|

|

|

| |

M0 |

−3604.36 |

40 |

OG |

0.27 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Pg11 |

0.44 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

OG |

0.27 |

|

|

|

| |

MP |

−3603.75 |

41 |

Pg11a |

0.38 |

vs. M0 |

1.22 |

0.27 |

| |

|

|

|

Pg11c |

0.50 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

OG |

0.27 |

|

|

|

| Pg11a/Pg11c |

MA |

−3604.19 |

41 |

Pg11early |

0.50 |

vs. M0 |

0.34 |

0.57 |

| |

|

|

|

Pg11late |

0.42 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

OG |

0.27 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Pg11aearly |

0.50 |

vs. MP |

0.72 |

0.70 |

| |

MPA |

−3603.39 |

43 |

Pg11cearly |

0.54 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Pg11alate |

0.35 |

vs. MA |

1.60 |

0.45 |

| Pg11clate | 0.49 | |||||||

*Note. Models: for M0, ω is allowed to take a different value only in the branch of the outgroup (OG); for MP, MA and MPA ω is allowed to take a different values according to the tested effect, i.e. “paralogs”, “age” or combined as explained in Figure 1. np: number of free parameters; logL: log-likelihood; LRT: likelihood ratio test statistic between indicated models; one (respectively two) asterisk indicates that the probability of observing such an LRT or higher under the compared model is <0.05 (respectively <0.01), assuming that the LRT follows a χ2 distribution with the difference of free parameters between the compared models as the number of degrees of freedom.

Interestingly, the three paralogs pairs exhibited contrasted results. The Lax2/Lax4 paralogs shows evidence for an age effect as shown by both a better fit of model MA relative to M0 (LRT = 13.0, p = 0.00031) and MPA versus MP (LRT = 13.8, p = 0.001) tests. We observed a marked increase of ω in early branches (ω = 0.14 compared with ω = 0.05 for late branches in MA). No significant paralog effect was detected and both paralogs Lax2 and Lax4 seem to be evolving under purifying selection (ω = 0.08 in M0, ω = 0.07 and ω = 0.10 for Lax2 and Lax4 respectively in MP model).

For the second paralog pair, Pg11/Pg3, both age (MA vs. M0, LRT = 4.84, p = 0.03) and paralog effects (MP vs. M0, LRT = 4.28, p = 0.04) are detected, but effects were weaker and marginally significant. The full model (MPA) did not provide a better fit relative to either the age or the copy models. The MA model showed an increase of ω in late branches (ω = 0.38 as compared to 0.22 in early branches) and an increase of ω in Pg11 (ω = 0.41 as compared to 0.25 in Pg3).

For the third and most recent pair of paralogous genes, Pg11a/Pg11c, no test was significant, suggesting that neither age nor paralog effects is playing a role or that the extent of nucleotide differences are too small for codon based models to have any power to detect heterogeneity in ω. The analysis shows that overall ω is markedly higher than in the other considered paralog pairs (ω = 0.44 for M0).

Analysis of selective pressures along genes: testing for positive selection

In order to investigate how ω varies along genes and in particular if positive selection signatures occurred we used models in which ω is allowed to vary among sites on each gene (Figure 2b). As in analysis of selective pressures along trees, when Pg11 gene is analysed, both sequences of Pg11a and Pg11c were considered. Since positive selection likely targets only a few amino acid positions, branch models used previously typically lack statistical power to detect positive selection as, in the branch model, ω is averaged over all the amino acid sites of the gene.

We compared the fit of models M8A and M8. The likelihood ratio test of M8 against M8A is a conservative test for positive selection, since the M8A model can account for an excess of neutral sites. No sites under positive selection were found for Lax2, Lax4 and Pg3. However the statistical test of M8 against M8A was significant for Pg11, Pg11a and Pg11c (p = 1.4 10-6, 9.99 10-3 and 1.26 10-4 respectively) (Table 2), showing that positive selection targeted both copies of Pg11. The fitted ω values suggest that positive selection was stronger for Pg11a (ω = 11.61 at positively selected sites) than for Pg11c (ω = 4.45) but affected fewer sites (frequency of 0.02, equivalent to 1 site, for Pg11a versus 0.10, equivalent to 5 sites, for Pg11c). The amino acid site detected under positive selection in Pg11a, with a probability of 0.98, is at position 141 and corresponds to a Glycine (G) in the precursor of the protein in M. truncatula [GenBank:AES65910]. At this position, M. ciliaris, M. polymorpha and M. ruthenica have a Lysine (K), M. rigiduloides a Serine (S) and M. coerulea an asparagine (N). Five amino acid positions under positive selection were detected in Pg11c. None of these 5 amino acid positions is the same than that detected in Pg11a. Three amino acid positions had an estimated posterior probability to be under positive selection greater than 0.95: position 110 (a Glutamic acid, E), position 132 corresponding to a Glutamine (Q) and position 303 corresponding to a Threonine (T) (position on the precursor protein in M. truncatula, [GenBank:AES65907]). At position 110, M. littoralis, M. tricycla and M. tornata have an Aspartic acid (D), and M. polymorpha an Asparagine (N). At position 132, the Glutamine of M. truncatula changes for a Threonine (T) in M. rigiduloides and M. noeana and for an Alanine (A) in M. polymorpha and M. coerulea. Finally, at position 303, all the species have a Methionine (M), except M. truncatula which has a Threonine (T), M. tricycla and M. tornata a Leucine (L) and M. polymorpha a Lysine (K). The two other sites had a posterior probability of 0.997 and 0.996, on a Tryptophan (T) in position 161 and an Alanine (A) in position 270, respectively. At position 161, M. rigiduloides, M. noeana, M. coerulea and M. ruthenica have a Histidine (H), M. polymorpha a (R), and M. rigidula an Asparagine (N). Finally, at position 270, M. littoralis, M. tricycla, M. rigiduloides and M. rigidula have a Serine (S), and M. noeana a Glycine (G).

Table 2.

Site models results: estimated parameters and log-likelihood ratio tests

| Gene | Model | np | logL | Parameters | LRT | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lax2 |

M8A |

35 |

−1600.22 |

p = 0.01 q = 2.86 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

ωad = 1 pad = 0.03 |

|

|

|

| |

M8 |

36 |

−1600.19 |

p = 0.01 q = 3.00 |

vs. M8A |

0.04 |

0.84 |

| |

|

|

|

ωad = 1.10 pad = 0.03 |

|

|

|

|

Lax4 |

M8A |

23 |

−1391.38 |

p = 6.30 q = 99.00 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

ωad = 1 pad = 0.00 |

|

|

|

| |

M8 |

24 |

−1391.38 |

p = 6.30 q = 99.00 |

vs. M8A |

0.00 |

1 |

| |

|

|

|

ωad = 1.00 pad = 0.00 |

|

|

|

|

Pg3 |

M8A |

23 |

−1616.24 |

p = 4.89 q = 99.0 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

ωad = 1.00 pad = 0.24 |

|

|

|

| |

M8 |

24 |

−1615.18 |

p = 0.13 q = 0.40 |

vs. M8A |

2.11 |

0.15 |

| |

|

|

|

ωad = 4.88 pad = 0.01 |

|

|

|

|

Pg11 |

M8A |

39 |

−2221.99 |

p = 2.16 q = 99.00 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

ωad = 1 pad = 0.36 |

|

|

|

| |

M8 |

40 |

−2210.38 |

p = 0.01 q = 20.01; |

vs. M8A |

23.22** |

1.44 10-6 |

| |

|

|

|

ωad = 6.30 pad = 0.04 |

|

|

|

|

Pg11a |

M8A |

19 |

−1388.97 |

p = 2.32 q = 89.36 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

ωad = 1.00 pad = 0.35 |

|

|

|

| |

M8 |

20 |

−1385.65 |

p = 0.47 q = 0.96 |

vs. M8A |

6.64** |

9.99 10-3 |

| |

|

|

|

ωad = 11.61 pad = 0.02 |

|

|

|

|

Pg11c |

M8A |

21 |

−1519.41 |

p = 0.01 q = 2.54 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

ωad = 1.00 pad = 0.32 |

|

|

|

| |

M8 |

22 |

−1512.06 |

p = 0.01 q = 0.05 |

vs. M8A |

14.69** |

1.26 10-4 |

| ωad = 4.45 pad = 0.10 | |||||||

Note. Models are M8A, ω following a β distribution discretized into 10 categories of similar frequency (0 < ω1–10 < 1) plus an additional category of ωad = 1, accounting for neutral sites; M8 differs from M8A only by the additional category of ω which is constraint to be superior to 1 (ωad > 1), to account for sites under positive selection.

Parameters are frequencies and values of ω for M8A and M8, p and q are the parameters in β distribution; for M8A and M8 pad and ωad are the frequencies and values of additional class of ω; NB ωad is fixed equal to one in M8A. np: number of free parameters; logL: log-likelihood; LRT: likelihood ratio test statistic between indicated models; one (respectively two) asterisk indicates that the probability of observing such an LRT or higher under the compared model is <0.05 (respectively <0.01), assuming that the LRT follows a χ2 distribution with the difference of free parameters between the compared models as the number of degrees of freedom.

Selective pressures along branches and sites of each paralog: testing for a “paralog” effect

In the third model we used, the clade model MD[33], ω varies among sites (with either two or three categories) and selective pressure at one class of sites is allowed to differ in the two clades of the phylogeny (Figure 2c). We tested the significance of MD models, with two (or three) categories of sites, compared to null M3 models (discrete model), which assume that two (or three) classes of sites are evolving under different levels of selective pressures, but without difference between clades. As in the previous sections, when the Pg11/Pg3 paralogs pair was analysed, both the sequences of Pg11a and Pg11c were considered for Pg11.

For the three paralogous gene pairs studied, models MD for which one class of ω is allowed to differ between paralogous gene clades were significantly better than null models M3 in which no variation between clades is allowed (Table 3). For the Lax2 and Lax4 paralogs tests comparing MD and M3 were significant when either two or three categories of ω were considered. For the other two pairs of paralogs, the test comparing MD and M3 was significant only when both models were defined with two categories of ω. These results revealed, for each pair, the presence of sites evolving under divergent selective pressures between the paralogous gene clades.

Table 3.

Branch-site models: estimated parameters and log-likelihood ratio tests

| Model (k) | np | LogL | LRT | P-value | prop | clade | ω | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

M3 (2) |

58 |

−2375.94 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lax2/Lax4 |

MD (2) |

59 |

−2369.54 |

vs. M3 (2) |

12.8** |

3.47 10-4 |

0.76 |

|

0.00 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.24 |

Lax2 |

0.15 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lax4 |

0.52 |

| |

M3 (3) |

60 |

−2375.94 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

MD (3) |

61 |

−2361.85 |

vs. M3 (3) |

28.17** |

1.11 10-7 |

0.77 |

|

0.005 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.03 |

|

0.97 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.20 |

Lax2 |

0.55 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lax4 |

0.97 |

| |

M3 (2) |

61 |

−3411.03 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pg11/Pg3 |

MD (2) |

62 |

−3407.95 |

vs. M3 (2) |

6.16* |

0.01 |

0.68 |

|

0.09 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.32 |

Pg3 |

0.74 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pg11 |

1.35 |

| |

M3 (3) |

63 |

−3400.58 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

MD (3) |

64 |

−3399.59 |

vs. M3 (3) |

1.98 |

1.16 |

|

|

|

| |

M3 (2) |

40 |

−2216.23 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pg11a/Pg11c |

MD (2) |

41 |

−2214.01 |

vs. M3 (2) |

4.45* |

0.03 |

0.79 |

|

0.12 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.21 |

Pg11a |

1.54 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pg11c |

3.13 |

| |

M3 (3) |

42 |

−2210.38 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MD (3) | 43 | −2209.37 | vs. M3 (3) | 2.01 | 0.16 | ||||

Note. Models: for M3 (discrete model), ω is free to take the number of values indicated in brackets (k); these values are homogenous in all branches of the tree; for MD, as explained in Figure 1 (b), one category of ω is allowed to differ between the two paralogous genes clades of the tree [33]. np: number of free parameters; logL: log-likelihood; LRT: likelihood ratio test statistic between indicated models; one (respectively two) asterisk indicates that the probability of observing such an LRT or higher under the compared model is <0.05 (respectively <0.01), assuming that the LRT follows a χ2 distribution with the difference of free parameters between the compared models as the number of degrees of freedom.

For Lax2/Lax4, none of the ω values was larger than 1, consistently with the result of the M8 versus M8A comparison. The model with three categories indicates that more than 77% of amino acid positions are very strongly constrained (ω very close to 0). The other two categories are allowed to vary between the two clades. For Lax2 a small proportion of sites is neutrally evolving (ω ~ 1) and the rest is mildly constrained (ω = 0.55), whereas in Lax4 both categories are effectively neutral (ω = 0.97).

For Pg11/Pg3 and Pg11a/Pg11c, the category of sites fixed across clades were also found to be under purifying selective pressure (ω = 0.09 and 0.12, respectively). When 2 categories of ω were considered, MD was significantly better than the null model M3 (LRT = 6.16, p = 0.01 and LRT = 4.45, p = 0.03 for the Pg11/Pg3 and Pg11a/Pg11c paralogs pairs respectively). The category of sites allowed to differ in MD model had a proportion of 32% and appeared to be nearly neutrally evolving in Pg3 (ω = 0.74) but under positive selection in Pg11 (ω = 1.35), as found with the M8 model. Concerning the Pg11a/Pg11c paralogous gene pair and as previously detected with site models, the MD model revealed that positive selection occurs for the Pg11a gene and for the Pg11c gene (ω = 1.54 and 3.13 respectively), but in addition MD actually detected a difference in the rate of positive selection between the paralogous copies, which appeared to be stronger in Pg11c.

Discussion

In this paper we examined patterns of molecular evolution of three paralogous gene pairs, in order to detect signatures of post-duplication functional divergence. We chose a time scale that allows analysing patterns of natural selection by examining patterns of nucleotide substitution of protein-coding sequences. With that aim, we focused on three sets of paralogs from the Medicago truncatula genome, Lax2/Lax4, Pg3/Pg11 and Pg11a/Pg11c. The duplications leading to these sets of paralogs occurred before the radiation of the 17 species studied but are still recent, as the three set of paralogs, Lax2/Lax4, Pg3/Pg11 and Pg11a/Pg11c, exhibit still 83, 72 and 88% nucleotide identity, respectively. Furthermore, we selected genes that are putatively involved in symbiotic functions, considering that interspecific interactions can involve both evolution of novelty (especially in the case of the legume-rhizobium symbiosis which evolved relatively recently) and co-evolutionary phenomena that are detectable through signatures of positive selection.

Models describing the evolutionary fate of duplicated genes once the duplication is fixed in the species suppose different forms of selective pressures [11]. First, according to the neofunctionalization model, i.e. evolution of a new function through functional divergence of one of the duplicated copies, selective pressures are expected to be asymmetrical between paralogs [1]. The copy fulfilling the ancestral function is expected to remain under purifying selection while the other copy is expected to experience a short period of relaxed constraint and then positive selection driving the acquisition of its new function. Second, the subfunctionalization model envisions the fixation of complementary degenerative mutations [12]. Under this model, relaxation of purifying selection is expected during the period of functional redundancy, and may allow the fixation of at least two complementary degenerative mutations (one in each gene). When both copies are jointly required to fulfil the ancestral gene function, purifying selection is still expected to be prevalent to maintain both copies. Although both models have been functionally validated, they are not exclusive and more complex scenarios combining the steps cited previously have been devised [15,25].

For all three studied paralogous gene pairs, the two copies exhibit different regimes of selection. This result suggests that these paralogous gene pairs have undergone at least some functional differentiation. Three different tests were used to qualify selective pressures governing the paralogs. The first one contrasted the average ω between paralog clades of the phylogeny and yielded significant differences only for Pg11/Pg3 (Table 1). The second test is specifically designed to detect positive selection affecting only a few sites of the sequence. We found signatures of positive selection in both Pg11a and Pg11c copies, and in Pg11 (Table 2). Finally, the clade model (Table 3) is a combination of branch and site models and allows investigating specifically the presence of sites evolving under divergent selective pressures between the paralogous genes and quantify its proportion. The clade model (MD) detected a significant increase of ω in Pg11 due to the occurrence of positive selection, as detected by the site model M8. For the paralogous pair Pg11a/Pg11c, branch models failed to detect any difference in selective pressure. Model D is more detailed and allows showing that sites under positive selection actually experience a stronger positive pressure in Pg11c than in Pg11a. Lax2 is the subject of an intense purifying selection whereas Lax4 harbours some sites (20% of sites) evolving quasi neutrally (ω = 0.97). The combination of these different tests provides a more complete picture of the selective pressures at work on each set of paralog. Since each single test addresses a single hypothesis, the comparison of several complementary tests allows acquiring a more complete picture. However, the clade model, which accounts for both variation of ω among branches and amino acid position, appears as the most informative for qualifying changes of selective constraint during duplicated genes evolution [33]. The only drawback is that it does not test formally for positive selection.

We observed that the Pg3 and Pg11c gene copies were pseudogenes in several species: in M. littoralis and M. tricycla for Pg3 and in M. tornata, M. rigidula and M. polymorpha for Pg11c. Since the three genes are present and potentially functional in, at least, four other species among those studied, we can hypothesise that the mutations affecting the function of these gene copies occurred, in some phylum, after the two successive rounds of duplications leading to the presence of three copies. This observation suggests that redundancy between copies is sufficient to have allowed the loss of one copy in several species.

Functional redundancy generated by multiple copies also implies periods of relaxed selection pressures, except if duplication itself is advantageous as it is the case, for instance, for a positive dose effect of copy number [11]. Redundancy is expected to occur with a larger probability when divergence between copies is slowed as it is the case of gene conversion [34]. The phylogenetic miss positioning we observed for four genes copies (Figure 1) may be explained by gene conversion. One way to test this hypothesis would be to sequence other individuals of M. tornata for example, in order to see if we could detect shared polymorphism between copies, which is a signature of gene conversion [11].

We detected sites under positive selection in Pg11 but not in Pg3. Rodriguez-Llorente et al.[26] suggested that Pg3 has been recruited by symbiosis after a duplication affecting an ancestral pollen-specific gene. The authors suggested that the modifications occurred essentially in the promoter region. Our results show that positive selection targeted both copies of Pg11 independently, possibly indicating the evolution of novel gene function. The polygalacturonase family contains members in organisms as distantly related as plants and eubacteria. In plants this gene family has been expanding dramatically through rounds of whole-genome duplications, segmental duplications and tandem duplications (66 and 59 copies in Arabidopsis thaliana and rice respectively) [35]. The high level of expansion of this family, generating periods of high redundancy, was probably accompanied by pseudogenization events, equivalent to those we detected in the Medicago genus. However as expression patterns are diverse between members of the family [35] subfunctionalization events were probably involved in the overall high retention rate of functional genes, notable in this family. Functional divergence among members of large gene families may also be driven by positive selection. Main examples in plants are disease resistance genes [36], transcription factors [37] or genes involved in development [38]. In our study, positive selection is detected in Pg11, resulting from the cumulative effects of positive selection in both Pg11a and Pg11c, the more recent duplicated gene pair we studied. Actually, this mode of selection does correspond to neither neofunctionalization nor subfunctionalization in their stricter definition. Subfunctionalization does not predict positive selection in either copy, while neofunctionalization predicts positive selection in only one copy (if detectable). Both copies could be under positive selection because they inherited, from the ancestral Pg11 gene, functions that imply regime of positive selection. Alternatively, neo-functionalization could involve adaptive differentiation of both copies (to avoid functional overlap), that would mediate adaptive evolution of both copies. Selection targets different sites in Pg11a and Pg11c and the strength of positive selection is different between them (Table 3). This observation is compatible with both models.

According to the clade models, the paralogs Lax2 and Lax4 experience different modes of selection. Both genes are mainly under purifying selection. Interestingly no pseudogenes were detected in Lax2 or in Lax4. The redundancy stage subsequent to the duplication generating Lax2 and Lax4 is not detectable anymore and may have been shorter than in Pg gene family. However, Lax4 appeared to be slightly, but significantly, less constrained than Lax2. According to the clade models (with 2 or 3 classes of sites, Table 3) a relaxation of constraint is observed for about 20% of the sites for Lax4 relative to Lax2. This means either that Lax4 acquired a function that implies less functional constraints or that both genes underwent subfunctionalization in such a way that the protein sequence of Lax4 is less constrained. Currently, the precise functions of Lax2 and Lax4 are not known. Both paralogs are expressed in shoot and roots of nodulating plants of M. truncatula. Lax2 is found in Expressed Sequence Tag (EST) libraries built from different tissues (2 in early seed development, 2 in flowers, early seeds, late seeds and stems, 2 in mixed root and nodules, 1 in nematode-infected roots, in developing flowers and phosphate-starved leaf). Lax4 is not found in EST libraries but expression of Lax4 was detected in shoots and roots of nodulating plants of M. truncatula[39].

The models contrasting ω in different branches allowed testing transient relaxation of purifying selection predicted to occur immediately after duplication. A significant increase of ω was detected in basal branches of the Lax2/Lax4 phylogeny. The opposite trend was detected for the Pg11/Pg3 pair, where purifying selection appeared to be actually weaker in late branches than in early branches, particularly for Pg11 (ω = 0.44). However, the value of ω in late branches was likely biased by the occurrence of positive selection in Pg11, because branch models average over all sites.

Conclusions

This study illustrates the multiplicity of mechanisms governing the evolutionary fate of duplicated genes and, in particular, the relative age of the duplication. Analysis of nucleotide substitution rates in gene coding sequence can discriminate between qualitative phenomenon (occurrence of positive selection) or quantitative differences (levels of ω between clades and its variation among branch and sites). Further studies of the factors governing evolution of duplicated genes will benefit from taking into account features of the evolution of gene families involving successive rounds of duplications.

Methods

Plant material

One accession was selected in sixteen diploid species of the Medicago genus: M. arabica, M. ciliaris, M. carstiensis, M. coerulea, M. laciniata, M. littoralis, M. marina, M. noëana, M. orbicularis, M. polymorpha, M. rigidula, M. rigiduloides, M. ruthenica, M. sauvagei, M. tornata, M. tricycla. Accession numbers, geographic location and mating systems are presented in Additional file 2.

Selection of duplicated genes

Genes were chosen on the basis of the Medicago truncatula line A17 whole genome sequence [28]. We selected two multigenic families meeting exhibiting recent rounds of duplications and involved in symbiosis-related functions. First, polygalacturonases (PG) form a gene family that is ubiquitous in the plant kingdom. These proteins are involved in the degradation of polysaccharides found in higher plants cell walls. The gene Pg11 is involved in pollen tube elongation in M. truncatula and is located on chromosome 2. Pg3, located on chromosome 5 in M. truncatula, has been shown to be involved in the tip growth of the infection thread during the establishment of the symbiosis with nitrogen-fixing bacteria Sinorhizobium sp. [26]. We also identified a more recent tandem duplication of Pg11, resulting in the paralogs Pg11a and Pg11c. The pairs Pg3Pg11c and Pg11aPg11c exhibit respectively 72 and 88% nucleotide sequence identity, and 62 and 81% amino acid sequence identity.

Second, we chose family of auxin efflux carrier, Lax (Like-Aux1), for which five members have been identified in Medicago truncatula[39]. Auxin is generally involved in the control of tissue growth and in particular during the development of nodules, the symbiotic organ hosting Sinorhizobium symbionts [40]. Auxin is synthesized in aerial organs (leaves and shoot apex) and is directionally transported. As a result, auxin carriers such as LAX proteins play an important role in auxin-controlled processes. We chose to study the youngest paralogous gene pair Lax2Lax4 that presents 83% of nucleotide identity, and 87% of amino acid identity. The sequence accession numbers are AY115843 and AY115844 respectively for Lax2 and Lax4.

Sequencing

To amplify specifically the coding region of each paralogous gene, we defined specific and non-specific primers. Non-specific primers were defined using the common sequence of both paralogous gene for each pair (i.e. not allowing to amplify separately each paralogs), whereas copy-specific primers were defined using polymorphism between the paralogs, available in the reference Medicago truncatula genotype A17. In a first step, specific primers combinations were used to amplify specifically each paralogs. Then, sequencing was performed using specific and/or non-specific primers. The primer sequences and their position on the genomic sequences of the five genes are available in Additional file 3 and Additional file 4 respectively. As divergence between species was often the cause of unsuccessful amplifications, several copy-specific primer pairs were defined to increase the chances of amplification in the sixteen studied species. Additional amplification rounds were performed to close sequencing gaps. For the most recent paralogs pair (Pg11a-Pg11c), the sequences obtained were labelled according to the primer combinations used for amplification and sequencing: when using primers designed for Pg11a (respectively Pg11c) , the sequencing product was qualified as ‘Pg11a’ copy (respectively ‘Pg11c’ copy).

Most sequences were obtained from genomic DNA, except for Lax2, which was sequenced from cDNA due to its large size. DNA extraction and genomic DNA amplifications and sequencing were performed as described in [41]. Total RNA was extracted from fresh leaves with a TRI REAGENT (T9424, Sigma®) buffer. Reverse transcription was done using the Reverse Transcription System kit from Promega®. Amplification and sequencing from cDNA were then performed as for genomic DNA. Chromatograph assembly and alignment were performed using programs of the Staden package v1.5 [42]. Visual inspection and correction of base calling and alignment were performed at this stage. The sequence editor Artemis v9 [43] was used to validate the reading frame and detect eventual frame shifts and/or premature stop codon mutation.

Outgroups

The Medicago truncatula sequence of gene Lax1 [GenBank:AY115841] was used as outgroup to root the Lax2Lax4 pair phylogeny. Lax1 diverged from Lax2 and Lax4 through a more ancient duplication [39]. Following the phylogenetic tree of the plants PG and endoglucanases published by Rodriguez-Llorente [26], we selected a PG coding sequence from Salix gilgiana [GenBank:AB029458] as outgroup for the Pg3-Pg11a/c phylogenetic tree. The M. truncatula copy of Pg3 was used as outgroup for the Pg11a- Pg11c pair phylogeny.

Phylogenetic analysis

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees were inferred using the PHYML program [44]. Maximum-likelihood analyses were conducted under the GTR molecular substitution model. Site to site variation in substitution rate was modeled by estimating the proportion of invariant sites and assuming that rates among the remaining sites were gamma distributed (4 categories were used to discretize the gamma distribution). The confidence level of each node was estimated using 100 bootstrap repetitions. Nucleotide and amino acid alignments of Lax genes are available in Additional file 5 and Additional file 6 respectively. Nucleotide and amino acid alignments of Pg genes are available in Additional file 7 and Additional file 8 respectively.

Variation in substitution rates was analyzed using codon substitution models where the parameter ω is defined as the ratio of non-synonymous (dN) to synonymous (dS) substitution rates [45]. We used eight models that make different assumption regarding variation of ω (Figure 2) in the phylogeny of each pair of paralogs. The first four models account of variation of ω among branches of the phylogeny [46] (Figure 2a). Model M0 assumes a single ω value for both paralogs. Model MP allows a “paralog effect” by assigning a different ω for each paralog clade in the tree. Model MA allows an “age effect” and assigns a single ω for the basal (ancestral) branch of both paralogs clades and a different ω to all other (more recent) branches within both clades. Model MPA allows for both levels of variation. All four models above are also specifying a specific ω parameter value on the branch leading to the outgroup of each paralog phylogeny. Total numbers of ω parameters are 2 for M0, 3 for MA and MP, and 5 for MPA.

Next, two models allowing for variation of ω among sites, but not among branches of the phylogenetic tree, and that are designed specifically to detect positive selection were used (Figure 2b) [47]. M8A assumes that a fraction of the sites experience purifying selection of varying intensity by assuming that ω omega values follow a beta distribution (0 < ω < 1). The remaining fraction of the site are assumed to evolve neutrally (ω = 1). M8A was used as null model for detecting positive selection by comparing its fit with M8 in which the additional category of ω is free to take any value above 1 (positive selection). The comparison of M8 versus M8A provides a (likelihood ratio) test for the occurrence of positive selection (identified when at least some sites exhibit a ω > 1). These two models were fitted separately to each paralog in the tree and excluding the outgroup, in order to detect positive selection occurring specifically on each copy.

The last two models are so called branch-site models that are combining variation of omega both among amino acid positions of the alignment and between different clades of the phylogeny, in our case each paralog clade (Figure 2c). These models allow testing variation of selective constraints between paralogous copies. Outgroup sequences are not considered in this analysis. The null model M3 allows either two or three rate categories that are homogeneous along the tree. Model MD (model D in [33]) allows selective pressure at one class of sites to differ in different clades of the phylogeny. Applied to our case, it is allowed to differ in each clade of paralogous gene (Figure 2c).

Maximum likelihood estimation of all model parameters was performed using the codeml software of the PAML package [48]. The different pairs of models are nested and were compared using likelihood ratio tests (LRTs).

Abbreviations

Pg: Polygalacturonase; Lax: Like-Aux1 (auxin efflux carrier); LRTs: Likelihood ratio tests; OG: Outgroup; EST: Expressed sequence tag.

Competing interests

The authors do not have any kind of financial or non-financial competing interest to declare in relation to this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

NC and JR conceived and designed research, JHH, IH and AW acquired data, JHH and NC processed data, JHH, NC and SDM analyzed data and NC, JHH, JR, SDM and TB wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Sequencing results. Table in PDF format presenting sequencing results for the five genes on the 17 species and GenBank accession numbers. Lengths are indicated in base pairs. The percentage that each sequence represents relative to the complete alignment is indicated in brackets when less than 100%. “na” and “ns” are indicated when an amplification failed and when the sequence was too short to be included in the analyses, respectively. Four sequences presented either point mutations resulting in a stop codon (Pg11c of M. laciniata), or a deletions inducing a frame shift in the coding sequence (Pg11c of M. ciliaris) or resulting in the appearance of a premature stop codon (for three sequences: Pg11c of M. orbicularis and Pg3 of M. littoralis and M. tricycla) are indicated by “pseudo”. Sequences with an unexpected position in the phylogeny are noted as “phylo_excluded”.

List of species used. Table in PDF format with list of sample used, germplasm accession number, life history, geographical area and ploidy level.

List of primers used. Table in PDF format with names and sequences of primers used for amplification and sequencing.

Schematic representation of genes and primers positions. Figure in PDF format with schematic representation of the intron/exon structure of the 5 sequenced genes on M. truncatula (A17) and position of the primers used for the amplification and sequencing, names and sequences of primers used for amplification and sequencing.

Lax gene Nucleotide alignment. Nucleotide alignment of Lax genes in phyml format.

Laxgene amino acid alignment. Amino acid alignment of Lax genes in phyml format.

Pggene nucleotide alignment. Nucleotide alignment of Pg genes in phyml format.

Pg gene amino acid alignment. Amino acid alignment of Pg genes in phyml format.

Contributor Information

Joan Ho-Huu, Email: joan.hohuu@hotmail.fr.

Joëlle Ronfort, Email: Joelle.Ronfort@supagro.inra.fr.

Stéphane De Mita, Email: demita@gmail.com.

Thomas Bataillon, Email: tbata@birc.au.dk.

Isabelle Hochu, Email: Isabelle.Hochu@supagro.inra.fr.

Audrey Weber, Email: Audrey.Weber@supagro.inra.fr.

Nathalie Chantret, Email: Nathalie.Chantret@supagro.inra.fr.

Acknowledgments

Sequencing was funded by an “AIP Genomes” grant by INRA. This work was also supported by ARCAD, a flagship project of the Agropolis Foundation.

References

- Ohno S. Evolution by gene duplication. London: George Allen and Unwin; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M. Genomic expansion by gene duplication. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates; 2007. (The origins of genome architecture). [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Conery JS. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science. 2000;290:1151–1155. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc G, Barakat A, Guyot R, Cooke R, Delseny M. Extensive duplication and reshuffing in the Arabidopsis genome. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1093–1101. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.7.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc G, Wolfe KH. Functional divergence of duplicated genes formed by polyploidy during Arabidopsis evolution. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1679–1691. doi: 10.1105/tpc.021410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L, Wall PK, Leebens-Mack JH, Lindsay BG, Soltis DE, Doyle JJ, Soltis PS, Carlson JE, Arumuganathan K, Barakat A. et al. Widespread genome duplications throughout the history of flowering plants. Genome Res. 2006;16:738–749. doi: 10.1101/gr.4825606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaillon O, Aury JM, Noel B, Policriti A, Clepet C, Casagrande A, Choisne N, Aubourg S, Vitulo N, Jubin C. et al. The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature. 2007;449:463–467. doi: 10.1038/nature06148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz J, Cannon SB, Schlueter J, Ma J, Mitros T, Nelson W, Hyten DL, Song Q, Thelen JJ, Cheng J. et al. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature. 2010;463:178–183. doi: 10.1038/nature08670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuskan GA, Difazio S, Jansson S, Bohlmann J, Grigoriev I, Hellsten U, Putnam N, Ralph S, Rombauts S, Salamov A. et al. The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray) Science. 2006;313:1596–1604. doi: 10.1126/science.1128691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel JF. Genome evolution in polyploids. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;42:225–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innan H, Kondrashov F. The evolution of gene duplications: classifying and distinguishing between models. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:97–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Force A, Lynch M, Pickett FB, Amores A, Yan YL, Postlethwait J. Preservation of duplicate genes by complementary, degenerative mutations. Genetics. 1999;151:1531–1545. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RC, Purugganan MD. The evolutionary dynamics of plant duplicate genes. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z, Steinmetz LM, Gu X, Scharfe C, Davis RW, Li WH. Role of duplicate genes in genetic robustness against null mutations. Nature. 2003;421:63–66. doi: 10.1038/nature01198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Zhang J. Rapid subfunctionalization accompanied by prolonged and substantial neofunctionalization in duplicate gene evolution. Genetics. 2005;169:1157–1164. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.037051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau JH, Sankoff D. Comparable rates of gene loss and functional divergence after genome duplications early in vertebrate evolution. Genetics. 1997;147:1259–1266. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.3.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WH, Yang J, Gu X. Expression divergence between duplicate genes. Trends Genet. 2005;21:602–607. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams KL. Evolution of Duplicate Gene Expression in Polyploid and Hybrid Plants. J Hered. 2007;98:136–141. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esl061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chain FJ, Ilieva D, Evans BJ. Duplicate gene evolution and expression in the wake of vertebrate allopolyploidization. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary B, Flagel L, Stupar RM, Udall JA, Verma N, Springer NM, Wendel JF. Reciprocal silencing, transcriptional bias and functional divergence of homeologs in polyploid cotton (gossypium) Genetics. 2009;182:503–517. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.102608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Marais DL, Rausher MD. Escape from adaptive conflict after duplication in an anthocyanin pathway gene. Nature. 2008;454:762–765. doi: 10.1038/nature07092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hittinger CT, Carroll SB. Gene duplication and the adaptive evolution of a classic genetic switch. Nature. 2007;449:677–681. doi: 10.1038/nature06151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayral P, Caminade P, Boursot P, Galtier N. The evolutionary fate of recently duplicated retrogenes in mice. J Evol Biol. 2007;20:617–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casneuf T, De Bodt S, Raes J, Maere S, Van de Peer Y. Nonrandom divergence of gene expression following gene and genome duplications in the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R13. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-2-r13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte JM, Cui L, Wall PK, Zhang Q, Zhang X, Leebens-Mack J, Ma H, Altman N, de Pamphilis CW. Expression pattern shifts following duplication indicative of subfunctionalization and neofunctionalization in regulatory genes of Arabidopsis. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:469–478. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Llorente ID, Perez-Hormaeche J, El Mounadi K, Dary M, Caviedes MA, Cosson V, Kondorosi A, Ratet P, Palomares AJ. From pollen tubes to infection threads: recruitment of Medicago floral pectic genes for symbiosis. Plant J. 2004;39:587–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprent JI. Evolving ideas of legume evolution and diversity: a taxonomic perspective on the occurrence of nodulation. New Phytol. 2007;174:11–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young ND, Debelle F, Oldroyd GE, Geurts R, Cannon SB, Udvardi MK, Benedito VA, Mayer KF, Gouzy J, Schoof H. et al. The Medicago genome provides insight into the evolution of rhizobial symbioses. Nature. 2011;480:520–524. doi: 10.1038/nature10625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavin M, Herendeen PS, Wojciechowski MF. Evolutionary rates analysis of Leguminosae implicates a rapid diversification of lineages during the tertiary. Syst Biol. 2005;54:575–594. doi: 10.1080/10635150590947131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bena G, Jubier MF, Olivieri II, Lejeune B. Ribosomal External and Internal Transcribed Spacers: Combined Use in the Phylogenetic Analysis of Medicago (Leguminosae) J Mol Evol. 1998;46:299–306. doi: 10.1007/pl00006306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele KP, Ickert-Bond SM, Zarre S, Wojciechowski MF. Phylogeny and character evolution in Medicago (Leguminosae): Evidence from analyses of plastid trnK/matK and nuclear GA3ox1 sequences. Am J Bot. 2010;97:1142–1155. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1000009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maureira-Butler IJ, Pfeil BE, Muangprom A, Osborn TC, Doyle JJ. The reticulate history of Medicago (Fabaceae) Syst Biol. 2008;57:466–482. doi: 10.1080/10635150802172168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielawski JP, Yang Z. A maximum likelihood method for detecting functional divergence at individual codon sites, with application to gene family evolution. J Mol Evol. 2004;59:121–132. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-2597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teshima KM, Innan H. The effect of gene conversion on the divergence between duplicated genes. Genetics. 2004;166:1553–1560. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.3.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Shiu SH, Thoma S, Li WH, Patterson SE. Patterns of expansion and expression divergence in the plant polygalacturonase gene family. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R87. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-9-r87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Cao Y, Wang S. Point mutations with positive selection were a major force during the evolution of a receptor-kinase resistance gene family of rice. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:998–1008. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.073080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Clegg MT, Jiang T. Excess non-synonymous substitutions suggest that positive selection episodes occurred during the evolution of DNA-binding domains in the Arabidopsis R2R3-MYB gene family. Plant Mol Biol. 2003;52:627–642. doi: 10.1023/a:1024875232511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Gu S, Wang X, Li W, Tang Z, Xu C. Molecular evolution of the CPP-like gene family in plants: insights from comparative genomics of Arabidopsis and rice. J Mol Evol. 2008;67:266–277. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9143-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel EL, Frugoli J. The PIN and LAX families of auxin transport genes in Medicago truncatula. Mol Genet Genomics. 2004;272:420–432. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-1057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desbrosses GJ, Stougaard J. Root nodulation: a paradigm for how plant-microbe symbiosis influences host developmental pathways. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mita S, Santoni S, Hochu I, Ronfort J, Bataillon T. Molecular evolution and positive selection of the symbiotic gene NORK in Medicago truncatula. J Mol Evol. 2006;62:234–244. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0367-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staden R. The Staden sequence analysis package. Mol Biotechnol. 1996;5:233–241. doi: 10.1007/BF02900361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford K, Parkhill J, Crook J, Horsnell T, Rice P, Rajandream MA, Barrell B. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:944–945. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman N, Yang Z. A codon-based model of nucleotide substitution for protein-coding DNA sequences. Mol Biol Evol. 1994;11:725–736. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. Likelihood ratio tests for detecting positive selection and application to primate lysozyme evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15:568–573. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Nielsen R, Goldman N, Pedersen AM. Codon-substitution models for heterogeneous selection pressure at amino acid sites. Genetics. 2000;155:431–449. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.1.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput Appl Biosci. 1997;13:555–556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sequencing results. Table in PDF format presenting sequencing results for the five genes on the 17 species and GenBank accession numbers. Lengths are indicated in base pairs. The percentage that each sequence represents relative to the complete alignment is indicated in brackets when less than 100%. “na” and “ns” are indicated when an amplification failed and when the sequence was too short to be included in the analyses, respectively. Four sequences presented either point mutations resulting in a stop codon (Pg11c of M. laciniata), or a deletions inducing a frame shift in the coding sequence (Pg11c of M. ciliaris) or resulting in the appearance of a premature stop codon (for three sequences: Pg11c of M. orbicularis and Pg3 of M. littoralis and M. tricycla) are indicated by “pseudo”. Sequences with an unexpected position in the phylogeny are noted as “phylo_excluded”.

List of species used. Table in PDF format with list of sample used, germplasm accession number, life history, geographical area and ploidy level.

List of primers used. Table in PDF format with names and sequences of primers used for amplification and sequencing.

Schematic representation of genes and primers positions. Figure in PDF format with schematic representation of the intron/exon structure of the 5 sequenced genes on M. truncatula (A17) and position of the primers used for the amplification and sequencing, names and sequences of primers used for amplification and sequencing.

Lax gene Nucleotide alignment. Nucleotide alignment of Lax genes in phyml format.

Laxgene amino acid alignment. Amino acid alignment of Lax genes in phyml format.

Pggene nucleotide alignment. Nucleotide alignment of Pg genes in phyml format.

Pg gene amino acid alignment. Amino acid alignment of Pg genes in phyml format.