Abstract

Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis (PLE) is a rare syndrome characterized by memory impairment, affective and behavioral disturbances and seizures. Among many different neoplasms known to cause PLE, small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is the most frequently reported. The pathogenesis is not fully understood but is believed to be autoimmune-related. We experienced a patient with typical clinical features of PLE. A 67-year-old man presented with seizure and disorientation. Brain magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated high signal intensity in the bilateral amygdala and hippocampus in flair and T2-weighted images suggestive of limbic encephalitis. Cerebrospinal fluid tapping revealed no evidence of malignant cells or infection. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography showed a lung mass with pleural effusion and a consequent biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of PLE associated with SCLC. The patient was subsequently treated with chemotherapy and neurologic symptoms gradually improved.

Keywords: Limbic Encephalitis, Paraneoplastic Syndromes, Lung Neoplasms

Introduction

Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis (PLE) is a rare kind of paraneoplastic neurologic syndrome characterized by confusion of acute onset, mood changes, hallucinations, loss of short term memory, and seizures. The commonly associated neoplasms are lung cancer (especially small cell lung cancer, SCLC), testicular tumor, thymoma, and ovarian cancer1. The pathogenesis is thought to be attributed to autoimmunity and the treatment is essential to improve its prognosis. We report a patient with seizure and disorientation who was diagnosed later as PLE combined with SCLC, and whose symptoms improved after chemotherapy.

Case Report

A 67-year-old male patient visited our emergency department via ambulance with the complaint of recurrent seizure-like activity and disorientation for 20 days. The patient was a current smoker (1 pack per day for 30 years) and had type 2 diabetes diagnosed 3 years previously. According to his wife, the patient first complained of involuntary head tilting to the right side at his office 20 days previously, which recovered spontaneously after 3~5 minutes. The same event occurred for several days. The patient seemed to be dull, unlike prior to the event, and sometimes replied incorrectly to a very simple question, similar to a patient with dementia. At admission day, while drinking a coffee with his wife at home, the patient suddenly lost his consciousness, fell down to the left side. The patient's body began to stiffen and, shortly thereafter, the arms and legs trembled for over 10 minutes. Emergency 119 was called immediately and the patient was transported to our emergency department.

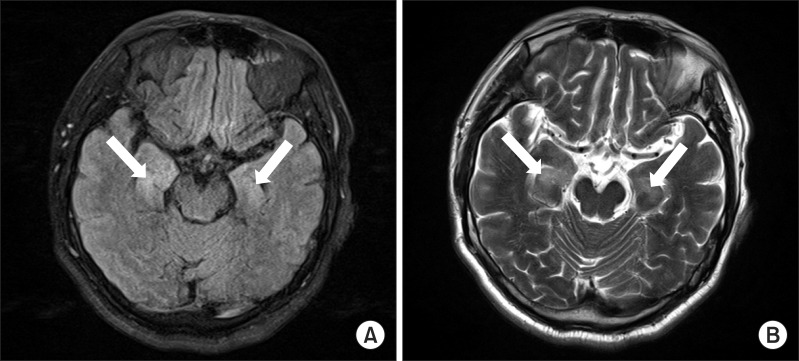

At the emergency room, the initial blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, body temperature was 36.7℃, pulse rate was 98 per minute and respiration rate was 20 per minute. The patient was stuporous and disoriented. Chest and abdominal examination showed no abnormality. On neurologic examination, both pupils were symmetric and light reflex was normal. Deep tendon reflex was normal and there was no Babinsky reflex. There were no Brudzinski or Kernig signs. On laboratory test, hemoglobin level was 14.8 g/dL, white blood cell (WBC) count was 13,200/µL, platelet count was 341,000/µL and blood glucose was 176 mg/dL. C-reactive protein, liver function test and urine test showed no abnormality. An electrocardiogram and chest X-ray was also normal. The tests for hepatitis B and C, venereal disease research laboratory and human immunodeficiency virus were negative. In addition, antinuclear antibody and rheumatoid factor were also negative. Vitamin B12 and folate levels were within normal limits. In cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, the opening pressure was 90 mm H2O, total WBC count was 20/µL (lymphocyte 84%), protein was 53 mg/dL and glucose was 114 mg/dL. Antibodies to herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, varicella zoster virus and Ebstein-Barr virus were all absent. Tuberculous polymerase chain reaction and cryptococcal antigen were also negative. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed hyperintensity on flair and T2-weighted image (T2WI) at bilateral amygdala and hippocampus suggestive of limbic encephalitis (Figure 1). On an electroencephalogram (EEG), there were epileptiform discharges at right frontotemporal area and general slow wave, suggestive of cerebral dysfunction.

Figure 1.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging showed high signal intensity on the flair (A) and T2-weighted image (B) in the bilateral amygdala and hippocampal area (arrows), compatible with limbic encephalitis.

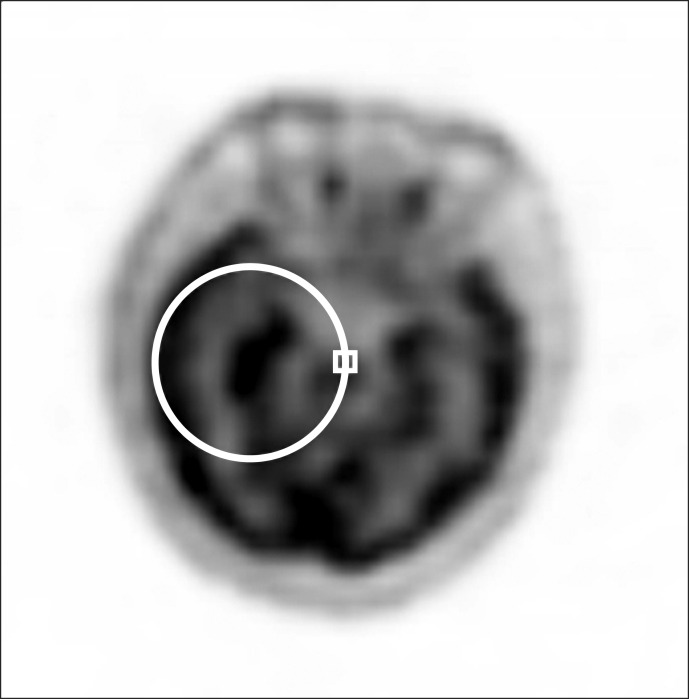

After admission, the patient had several generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Antiepiletics such as oxcarbamazepine were administered and the seizures soon disappeared. In addition, the antiviral agent acyclovir was used tentatively because the clinical manifestation and brain imaging were suggestive of herpes simplex encephalitis. As other causes of limbic encephalitis, we suspected the possibility of hidden malignancy and checked tumor makers, paraneoplastic autoantibodies (PAA) and whole body positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT). PAA such as anti-Hu, anti-Ri, anti-Yo, and anti-NMO antibodies were all negative, but the carcinoembryonic antigen tumor marker were increased to 28.5 ng/mL (normal range, 0~5 ng/mL). Whole body PET/CT revealed hypermetabolic lesion at right medial temporal lobe of brain which was compatible with limbic encephalitis as showed on MRI (Figure 2). In addition, there was hypermetabolism at right pleura and right lower lobe suggestive of lung cancer with malignant effusion. We consequently performed chest CT and CT-guided percutaneous needle biopsy and finally diagnosed the patient with PLE associated with SCLC. On the next day of pathologic confirmation, we started combination chemotherapy with etoposide and carboplatin. The patient was maintained on oral phenytoin, oxcarbamazepine and valproate via levine tube during the treatment. Until the 4th cycle of chemotherapy, the patient was free from seizure and the initial neurologic symptoms gradually improved. Follow-up EEG showed only slow wave without epileptiform discharge. In the outpatient clinic, the patient maintains his antiepileptics without any chemotherapy- related complication and is planning to continue next cycle of chemotherapy.

Figure 2.

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography showed hypermetabolism in the bilateral amygdala and hippocampal area and is more prominent at the right mediotemporal area (circle).

Discussion

Paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes are a heterogenous group of neurologic disorders associated with malignancy. They are caused by a mechanism other than metastases, infections, metabolic disorder, or side effects of cancer treatment. These rare syndromes occur in about 6.6% of patients with malignancy and may affect any part of the nervous system including cerebrum, spine, neuromuscular junction and muscle, either damaging one or multiple sites2.

PLE, one of the paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes, refers to an inflammatory process localized to the limbic system, which is associated with neoplasm. It is characterized by acute or subacute mood and behavioral changes, short-term memory loss, seizures and cognitive dysfunction. The symptoms typically progress over days to weeks but more indolent presentations over months have been described1. The most frequent associated malignancy is lung cancer (especially SCLC) but testicular tumors, thymoma, breast cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma can be related with PLE2,3.

The pathobiology of PLE is believed to be autoimmune-related. The mechanism is suggested to be triggered by autoantibodies against onconeural antigens which are common to both the cancer and the nervous system4. Among several PAAs, the most frequent are anti-Hu and anti-Ma2 antibodies. The presence of PAA often allows early detection of the associated tumor, thus aiding the diagnosis, however these antibodies are detected in only 60% of patients diagnosed with PLE. Therefore, the absence of PAA does not exclude PLE5,6. According to the detected PAA, the clinical manifestation can vary. For example, patients with anti-Hu (also known as antineural nuclear antibody type 1, ANNA-1) antibody often have multifocal neurologic involvement affecting temporal lobes, brainstem, cerebellum and dorsal roots7. SCLC is most frequently found malignancy associated with anti-Hu antibody1. On the other hand, testicular cancer is associated with anti-Ma2 (also called anti-Ta) antibody and the clinical presentation of Ma2-associated encephalitis differs from classical PLE in that its symptoms particularly related with brainstem and cerebellar dysfunction8.

A brain MRI is helpful in that one can exclude other causes with similar neurologic symptoms. Characteristic MRI finding of patients with PLE is high signal intensity on flair or T2WI in bilateral or unilateral medial temporal lobes and/or brain stem9. EEG has limited usefulness in making the diagnosis of PLE, but it is useful to exclude nonconvulsive seizures. In patients with PLE, nonspecific EEG abnormalities are common and include focal or generalized slowing, epileptiform activity and periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges10. CSF tapping should be performed to exclude the leptomeningeal metastasis and to detect other inflammatory or immune-mediated neurologic disorder. CSF finding is not specific for PLE and often shows mild elevation of protein level or monocyte count11.

The diagnosis of PLE is difficult to diagnose for several reasons1-3. First, similar symptoms such as seizure, memory loss, irritability, depression, confusion or dementia can be caused by many other cancer-related complications, including brain metastasis, toxic and metabolic encephalopathies, infections and side effect of cancer therapy. Second, the clinical manifestation and frequently involved brain area is especially similar with those of herpes simplex encephalitis. Finally, neurologic symptoms frequently precede the detection of the tumor, further confounding the diagnosis of the neurologic disorder as paraneoplastic in origin. Gultekin et al.1 suggested the following diagnostic criteria: a compatible clinical picture; an interval of <4 years between development of neurologic symptoms and tumor diagnosis; exclusion of the other neuro-oncological complications; and at least one of the following: CSF with inflammatory changes but negative cytology, MRI demonstrating temporal lobe abnormalities or EEG showing epileptic activity in the temporal lobe. In the current case, the patient had neurologic symptoms and brain imaging findings suspicious of limbic encephalitis, and we could exclude other causes by CSF analysis. Although the PAAs were negative, we suspected underlying hidden neoplasm and finally diagnosed PLE with SCLC.

Unlike most paraneoplastic syndromes of the central nervous system, which do not improve with treatment, PLE is well- known for its good response to therapy. In a case series of 50 patients of PLE, the response rate of neurologic manifestation to the treatment was over 60%1. Immnunosuppression with methylprednisolone, intravenous immunoglobulin can be available. Kobayakawa et al.12 reported that plasma exchange could be useful to control symptoms by reducing the titer of PAA. However, treatment of associated tumor is more important in neurologic improvement and prognosis13. Bowyer et al.14 reported two cases of PLE with SCLC which were successfully treated after chemotherapy stressing the importance of identifying underlying malignancies, while Cho et al.15 reported a case whose prognosis was poor due to delayed diagnosis. The present case also demonstrated the importance of early diagnosis and treatment of underlying cause.

We report a case of a patient admitted due to seizure and disorientation, and finally diagnosed as PLE associated with SCLC, whose neurologic symptoms were gradually improved with treatment of underlying malignancy. Although the diagnosis PLE is often difficult and exclusion of other causes of encephalitis is essential, all efforts should be made to find a hidden neoplasm when encountering symptoms compatible with limbic encephalitis. It is also important to remember that PLE is a potentially 'controllable' disorder with early diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

References

- 1.Gultekin SH, Rosenfeld MR, Voltz R, Eichen J, Posner JB, Dalmau J. Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis neurological symptoms, immunological findings and tumour association in 50 patients. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 7):1481–1494. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.7.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darnell RB, Posner JB. Paraneoplastic syndromes involving the nervous system. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1543–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalmau J, Rosenfeld MR. Paraneoplastic syndromes of the CNS. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:327–340. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70060-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graus F, Delattre JY, Antoine JC, Dalmau J, Giometto B, Grisold W, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for paraneoplastic neurological syndromes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1135–1140. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.034447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alamowitch S, Graus F, Uchuya M, Reñé R, Bescansa E, Delattre JY. Limbic encephalitis and small cell lung cancer: clinical and immunological features. Brain. 1997;120(Pt 6):923–928. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.6.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graus F, Dalmau J. Paraneoplastic neurological syndromes: diagnosis and treatment. Curr Opin Neurol. 2007;20:732–737. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282f189dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sillevis Smitt P, Grefkens J, de Leeuw B, van den Bent M, van Putten W, Hooijkaas H, et al. Survival and outcome in 73 anti-Hu positive patients with paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis/sensory neuronopathy. J Neurol. 2002;249:745–753. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-0706-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalmau J, Graus F, Villarejo A, Posner JB, Blumenthal D, Thiessen B, et al. Clinical analysis of anti-Ma2-associated encephalitis. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 8):1831–1844. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cakirer S. Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis: case report. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2002;26:55–58. doi: 10.1016/s0895-6111(01)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawn ND, Westmoreland BF, Kiely MJ, Lennon VA, Vernino S. Clinical, magnetic resonance imaging, and electroencephalographic findings in paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:1363–1368. doi: 10.4065/78.11.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakheit AM, Kennedy PG, Behan PO. Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis: clinico-pathological correlations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53:1084–1088. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.53.12.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobayakawa Y, Tateishi T, Kawamura N, Doi H, Ohyagi Y, Kira J. A case of immune-mediated encephalopathy showing refractory epilepsy and extensive brain MRI lesions associated with anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2010;50:92–97. doi: 10.5692/clinicalneurol.50.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vedeler CA, Antoine JC, Giometto B, Graus F, Grisold W, Hart IK, et al. Management of paraneoplastic neurological syndromes: report of an EFNS Task Force. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:682–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowyer S, Webb S, Millward M, Jasas K, Blacker D, Nowak A. Small cell lung cancer presenting with paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2011;7:180–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-7563.2010.01374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho TY, Kim YJ, Lee BI, Huh K. A case of limbic encephalitis associated with small cell lung cancer about diagnostic MRI findings. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 1994;12:338–342. [Google Scholar]