Abstract

PURPOSE

The purpose of this study was to analyze the current literatures and to assess outcomes of implant treatment in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Studies considered for inclusion were searched in Pub-Med. The literature search for studies published in English between 2000 and 2012 was performed. Our findings included literature assessing implant treatment in patients with a history of generalized aggressive periodontitis (GAP). All studies were screened according to inclusion criteria. The outcome measures were survival rate of superstructures, marginal bone loss around implant and survival rate of implants. All studies were divided into two follow-up period: short term study (< 5 years) and long term study (≥ 5 years).

RESULTS

Seven prospective studies were selected, including four short-term and three long-term studies. The survival rates of the superstructures were generally high in patients with GAP, i.e. 95.9 - 100%. Marginal bone loss around implant in patients with GAP as compared with implants in patients with chronic periodontitis or periodontally healthy patients was not significantly greater in short term studies but was significantly greater in long term studies. In short term studies, the survival rates of implants were between 97.4% and 100% in patients with GAP-associated tooth loss, except one study. The survival rates of implants were between 83.3% and 96% in patients with GAP in long term studies.

CONCLUSION

Implant treatment in patients with GAP is not contraindicated provided that adequate infection control and an individualized maintenance program are assured.

Keywords: Agrressive periodontitis, Dental implants, Dental implantation, Systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis has been classified into chronic and aggressive subtypes.1 Aggressive periodontitis is characterized by rapid progression and destruction of periodontal tissue.1,2 It often occurs in the early decades of age in systemically healthy patients. Familial aggregation is often at play, as well. This disease occurs in localized and generalized forms. Generalized aggressive periodontitis (GAP) is characterized by the involvement of at least three permanent teeth other than first molars and incisors. It usually affects people under 30 years of age, but patients may be older. GAP is frequently associated with Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis. It is believed that these patients may have a deficiency in the host immune system.2

Patients with GAP may lose most of their teeth due to severe attachment loss of affected teeth. When these teeth are replaced, often the treatment of choice will be implant-supported restorations. But there was a controversy on the treatment with dental implants in patients with GAP. A recent study reported that they detected the periodontal pathogen such as A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis in the edentulous subjects who were edentulous for at least 1 year, although these species were thought to disappear after extraction of all natural teeth.3 Periodontal pathogens may be transmitted from teeth to implants, implying that periodontal pockets may serve as reservoirs for bacterial colonization around implants.4,5 Similar inflammatory mechanism of peri-implantitis and aggressive periodontitis has been discussed.6 The similarity in microbial flora responsible for aggressive periodontitis and peri-implantitis supports the concept that periodontal pathogens may be associated with peri-implant infections and failing implants. Some clinicians can have fear that the pathogen of aggressive periodontitis can remain after extraction of infected tooth provoke the peri-implantitis and implant loss.

In recently published systematic reviews, the outcome of implant treatment in patients with and without a history of periodontal disease-associated tooth loss has been analyzed.7-11 However, the outcome of implant treatment in patients with GAP associated tooth loss have not been studied previously in a systematic review, except one study. The existing review surveyed 4 case reports and 5 longitudinal studies published through May 2007. Most studies involved less than a 3-year follow-up period.12 Our review contains 4 more longitudinal studies published in May 2007. Three studies of those involved more than a 3-year follow-up period.

The purpose of the present systematic review was to analyze the current literatures and to assess the outcomes of implant treatment in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Studies considered for inclusion were searched in electronic database, Pub-Med. The literature search was conducted for studies published in English from January 2000 to september 2012 using the following search terms "dental implant", "dental implantation", "aggressive periodontitis".

1 exp Dental implant

2 exp Dental implantation.

3 exp Aggressive periodontitis.

4 1 or 2.

5 3 and 4.

All Studies were screened according to inclusion criteria: 1) limited to human study, 2) ramdomized controlled trials (RCTs) or prospective or retrospective studies, 3) at least 5 patients, 4) mean follow-up period was at least 1 year. The exclusion criteria consisted of in vitro studies, publications comparing different patients group but not presenting separate survival rates, patient records only, no data on number of patients and no survival rates of implants. The screening of the titles of the identified studies was initially performed. The abstract was assessed when the title presented that the study fulfilled the above-described inclusion criteria. Full-text reading was performed when the abstract indicated that the inclusion criteria were fulfilled. One reviewer (Kim) carried out the study selection. Two authors (Kim and Sung) conducted independently the quality assessment of included studies and the data-extraction process. If disagreement between the two reviewers was indicated, agreement was achieved by discussion. All studies were divided into two categories according to follow-up period; short term study (< 5 years) and long term study (≥ 5 years).

Treatment outcome measures included 1) survival rates of superstructures, 2) marginal bone loss around implant, 3) survival rates of implants. Implant survival was defined as not needing extraction at the time of examination. Because of the variation in the design of the different studies, it was not possible to perform a statistical analysis for the data obtained.

RESULTS

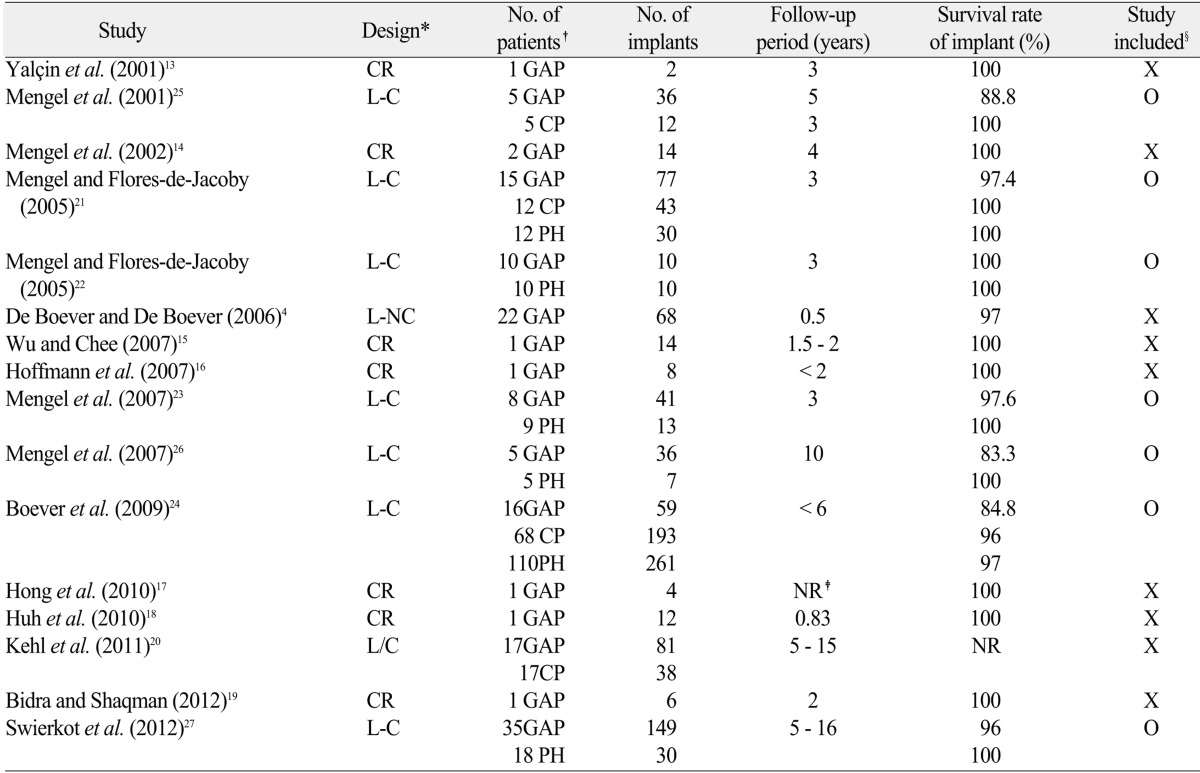

The initial database search yielded 56 articles. 22 abstracts were reviewed and 16 full-text articles were screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, seven studies were included (Table 1). The reason for exclusion was: less than 5 patients included,11-18 follow up period < 1 year4 and no cumulative survival/success rate for implant.19 The seven studies are described and summarized in Table 2, 3. No RCTs were identified. 7 longitudinal studies with control were selected.21-27 These included four short-term (Mengel and Flores-de-Jacoby,21 Mengel and Flores-de-Jacoby,22 Mengel et al.,23 De Boever et al.24) and three long term studies (Mengel et al.,25 Mengel et al.,26 Swierkot et al.27). One study reported that 23% of the implants were followed for > 5 years and 13.8% for > 6 years in the chronic periodontitis/GAP group. However mean follow-up period was 46.8 ± 26.7 months in GAP group.24 This study was categorized as short term study. Other study reported that the aggressive periodontitis cases were followed for 5 years, whereas chronic periodontitis cases were followed for 3 years. 25 This study was categorized as long term study.

Table 1.

Simple summary of studies

*CR: case report, L-C: longitudinal study with control, L-NC: longitudinal study without control.

†GAP: generalized aggressive periodontitis, CP: chronic periodontitis, PH: periodontally healthy.

‡NR: not recorded.

§O: study included, X: study excluded.

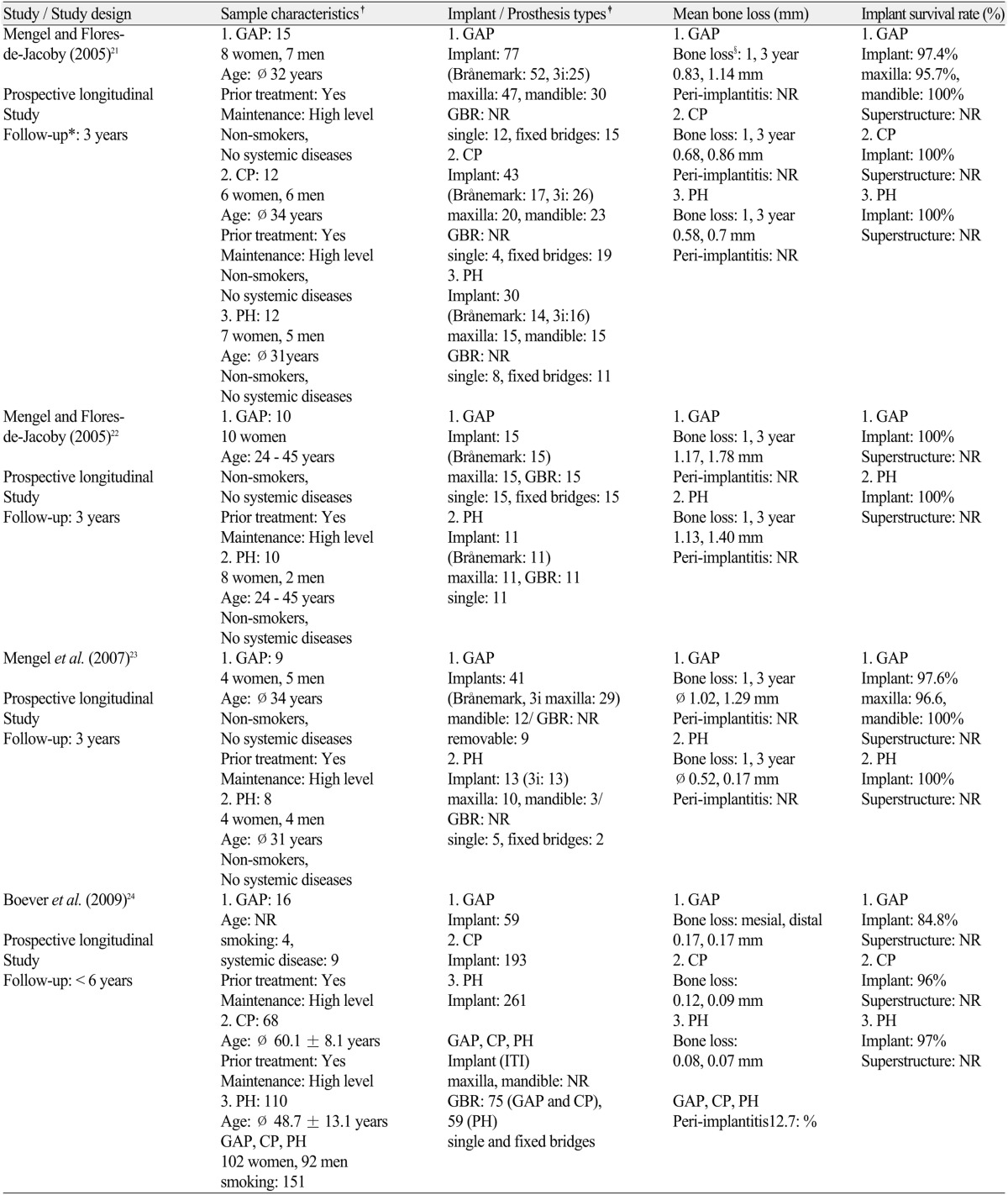

Table 2.

Summary of studies on implant treatment in patients with GAP involving < 5-year follow-up (Short term study)

*Follow up period: after insertion of superstructure.

†Age: at the time of implant placement, Ø: mean value.

‡GBR: guided bone regeneration, single: single tooth replacement, fixed bridges: implant supporting bridge, removable: removable denture.

§Bone loss: marginal bone level was measured.

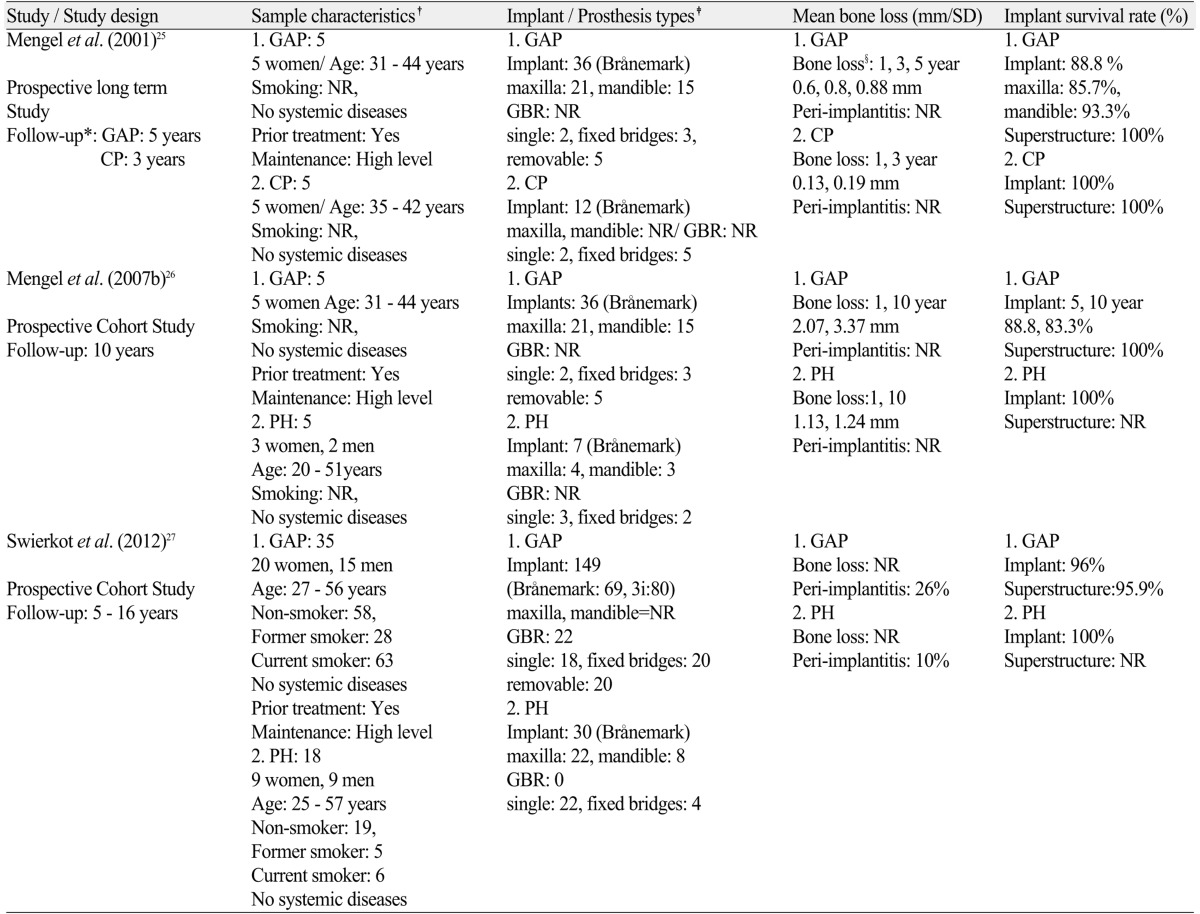

Table 3.

Summary of studies on implant treatment in patients with GAP involving ≥ 5 year follow-up (Long term study)

*up period: after insertion of superstructure.

†Age: at the time of implant placement, Ø: mean value.

‡GBR: guided bone regeneration, single: single tooth replacement, fixed bridges: implant supporting bridge, removable: removable denture.

§Bone loss: marginal bone level was measured.

All of included studies observed two or three groups of the following subjects: 1) patients with periodontal disease classified as GAP. Patient with GAP revealed a generalized clinical attachment loss (≥ 3 mm within 1 year) of more than three teeth (excluding incisors and first molar); 2) periodontally susceptible patients with tooth loss due to chronic periodontitis classified as CP. Patient with CP revealed a generalized clinical attachment loss (< 3 mm within 1 year) of more than three teeth; and 3) periodontally healthy patients (PH) not susceptible to periodontal disease in which teeth should be treated because of loss due to trauma, caries or agenesis. The diagnosis and subdivision were based on the criteria described by Armitage.1

Most studies focused on partially edentulous patients. Although the number of individuals with each patient group varied between 5 and 110, most groups involved less than 16 patients with GAP. The age of patients with GAP was between 24 and 56 years. Three studies22,25,26 involved only women. Three studies22,23,27 involved non-smokers, and two studies25,26 did not recode. Only one study24 contained patients with systemic disease. The number of inserted implant was between 15 and 149.

Survival rates of superstructures

The type of superstructure varied with fixed prostheses being dominant. The survival rates of the superstructures in patients with GAP have been mentioned in three studies. In two long term studies, survival rate of superstructure were 100%.25,26 and in one long-term study, survival rate of superstructure was 95.9%.27

Marginal bone loss around implant

Short term studies

Mengel and Flores-de-Jacoby compared survival of implants placed in 12 PH, 12 CP, and 15 GAP patients. Marginal bone loss around implants was 1.14 mm in the GAP, 0.86 mm in the CP and 0.70 mm in the PH subjects in the 3 years after insertion of the superstructure. However, this difference did not show statistical significance.21 In another publication, the same authors reported on the survival of implants placed in 10 PH patients, as well as implants placed 6 to 8 months after guided bone regeneration (GBR) procedures in 10 patients treated for GAP. The 3-year bone loss around the implants placed in regenerated bone in patients treated for GAP was 1.78 mm, while in the PH subjects it was 1.4 mm. However, no significant differences were seen in the results between the groups.22 Mengel et al., following a 3-year observation period, reported that it was slightly greater in GAP patients around implants (1.29 mm) than in patients with PH (0.71 mm). However, it revealed no significant difference in the GAP and the PH groups.23 De Boever et al. compared survival of implants placed in 110 PH, 68 CH, and 16 GAP patients. They reported that marginal bone loss per year was 0.08 and 0.07 mm in PH patients and 0.17 and 0.17 mm in GAP patients. on mesial and distal sides around of implants. In the GAP group, there was significantly more bone loss whereas the PH group showed significantly less bone loss around the implants.24

Long term studies

Mengel et al. reported on survival of 36 implants placed in 5 patients treated for GAP and 12 implants placed in 5 patients treated for CP. The marginal bone loss at the implants of the GAP patients was 0.6 mm in the first year after insertion of the superstructure, with a reduction in subsequent years to 0.28 mm. Marginal bone loss around implants was 0.80 mm after 3 years after insertion of the superstructure and 0.88 mm after 5 years. In the CP patients it was lower in the first year (0.13 mm) as well as in the 2 subsequent years (0.06). The total marginal bone loss around implants was 0.19 mm in the first 3 years after insertion of the final abutments. Marginal bone loss at the implants in the 3 years was significantly higher in the GAP patients. In another study, total marginal bone loss was 3.37 mm in the GAP patients and 1.24 mm in the PH subjects after the 10-years. Marginal bone loss at the implant of the GAP patients was significantly greater than in the PH subjects.26 Swierkot et al.27 did not record about bone loss around implants.

Survival rates of implants

Short term studies

Mengel & Flores-de-Jacoby reported that the 3-year implant survival rate was 100% in the PH and CP patients, and 97.4% of GAP patients. Two GAP patients each had one implant removed in the first year after insertion due to mobility. There were no significant differences for the implant survival rate between the three groups.21 The same study group reported that the 3-year implant survival rate was 100% in the GAP and the PH group.22 Another a 3-year prospective study by Mengel and colleagues reported that implant success rates were 100% in PH patients and 97.6% in GAP patients. No significant differences were seen in the results between the groups.23 De Boever et al. report that the 46.8 ± 26.7 months implant survival rate was 84.8% in the GAP group and 96% in the CP group, and the 48.1 ± 25.9 months implant survival rate was 97% in the PH group. The PH patients and the patients with CP showed no difference in implant survival rate, but GAP group had lower implant survival implant rate.24

Long term studies

Mengel et al. reported on a 5-year implant survival rate of 88.8% in GAP group and 100% in CP group. The 4 of the 36 implants in the GAP group were lost. Implant survival rate was significantly lower in the GAP group.25 Another study reported that the 10-year implant survival rates were 83.3% in GAP patients and 100% in PH patients. The 6 of the 36 implants in the GAP patients were lost. In the GAP patients, a significantly lower implant survival rate was shown.26 Swierkot et al. reported on the result showed implant survival rates of 100% in PH subjects versus 96% in GAP patients. However the implant success rate was 33% in GAP patients and 50% in PH subjects. GAP patients had 5 times greater risk of implant failure.

DISCUSSION

There is a controversy about whether implant treatment in patients with previous tooth loss due to GAP is characterized by an increased incidence of peri-implantitis and implant loss. A study conducted over 18 months reported that in one patient with GAP, inflammation or marginal bone loss was not found in all implants. The survival rate of implants was 100%.15 Another studies reported on one similar case with a positive outcome.13,15-19 However, These studies had shot follow-up period and only one patient included.

This present review analyzed studies with at least 3 years follow-up period and at least 5 patients. Seven longitudinal studies with control were selected.21-27 These included four short-term and three long term studies.

The survival rates of the superstructures were reported in three studies, they were generally high, i.e. 95.9 - 100% in patients with GAP.25-27 The type of superstructure varied, but fixed prostheses dominated.

The presentation of data bone loss around implants from the studies in this systematic review varied. Most authors reported bone data as marginal bone loss. In short term studies, Mengel and Flores-de-Jacoby described that comparison of the annual bone loss at the implants revealed slightly, but not significantly, greater loss in the GAP patients than in the PH and the CP patients.21-23 However, De Boever et al. reported that PH patients and patients with CP show no difference in peri-implant variables, but patients with GAP have more marginal bone loss, and more peri-implantitis.24 In long-term studies, marginal bone loss in patients with GAP as compared with implants in PH patients or CH patients showed significantly higher incidence.25,26 These long term studies suggest increased susceptibility to progressive marginal bone loss around implants in patients with GAP. Therefore, marginal bone loss at implants in patients with GAP as compared with implants in PH patients or CP patients was not significantly greater in short term studies but was significantly greater in long term studies.

The reported short-term implant survival rates in patients with GAP were 97.4%,21 reaching up to 100% in three studies21-23 with a 3 year follow-up period from the same research group. All patients was nonsmokers and had no systemic diseases in three studies. Mengel & Flores-de-Jacoby found that the 3-year implant survival rate was 100% in the PH and CP patients, and 97.4% in the GAP patients.21 In another publication, the bone in the region of the extraction spaces was augmented by the GBR technique in preparation 6-8 months prior to implant placement. The 3-year implant survival rate was 100% in GAP and PH subjects.22 All implants were placed in the region with sufficient bone because of previous GBR, and all prostheses were single crown without unpredictable loading. All patients was nonsmokers, and had no systemic diseases. In addition, the strict prior treatment and high level maintenance was performed. The implant survival rate of high score seems to be a natural outcome. Implant survival rates were 100% in the healthy patients and 97.6% in the GAP patients within study by Mengel et al.23 Double crown-retained removable dentures was used in this study. All peri-implant and periodontal tissues remain uncovered, which guarantees improved oral hygiene, especially in patients with a history of periodontal disease. In above three studies, a direct comparison of the two or three groups of patients for the duration of the 3-year observation period did not show any significant differences in terms of clinical and radiologic parameters. However, De Boever et al. found patients suffering from GAP have more peri-implant pathology, more bone loss and a lower survival rate. In about 4 year average follow-up period, implant survival rate was 97% in the PH patients, 96% in the CP patients, and 84.8% of GAP patients. This study reported that smoking and impaired health status have a significant influence only on implant survival in the GAP group. Smoking habits had a significant influence on implant survival only in the GAP group, declining in current smokers to 63%, and to 78% in former smokers. Impaired health occurred in six out of the 16 patients. In one GAP patient with diabetes and Parkinson's disease, all three implants failed. The simultaneous presence of both factors further reduces the survival rate in the GAP group.24

The reported long-term implant survival rates in patients with GAP were 83.3%,26 reaching up to 96%.27 Mengel et al. found more peri-implantitis and implant failure in patients with GAP. The 5 years implant success rate was 88.8% (maxilla: 85.7%, mandible: 93.3%) in patients with GAP and 100% in patients with CP. In patients with GAP, the following failure: two implant in the maxilla remained as sleeping implants, one implant in the maxilla was removed during second stage surgery because of mobility, one implant in the mandible displayed mobility 1 month after insertion of superstructure was removed. A closer look at the failures suggested that periodontal disease was not responsible for leaving two implants sleeping. Periodontal disease might play a role only in that previous progressive bone loss, for example, leads to unfavorable alveolar ridge conditions and limited opportunities for implantation.25 Mengel et al., following a 10-year observation period, reported that the implant survival rate was 83.3% in patients with GAP and 100% in patients with PH. The 6 of the 36 implants in the GAP patients were lost. The 3 implants were removed, one implant remained as sleeping. Two implants were remaining but classified as failure implants.26 The reason for two more failure was more bone loss than specified by the success criteria of Albrektsson et al.28 However, although 2 implants showed more bone loss than specified by Albrektsson et al.,28 they were not removed and still working. The 83.3% is success rate and is not survival rate. If the survival rate of implant was recalculated it was 88.8% in patients with a GAP. Swierkot et al. reported that the survival rate was 96% in GAP patients and 100% in PH subjects. However, implant success rate was 33% in GAP patients and 50% in PH subjects. Former smokers and GAP patients had a significantly higher risk. There were no patients with systemic disease.27

Numerous studies have reported the influence of smoking on implant success, finding that smoking increases the risk of implant failure.24,29-31 A 10-year longitudinal study found a greater bone resorption among smokers.32 The short term study found smoking habits had a significant influence on implant survival only in the GAP group, declining in current smokers to 63%, and to 78% in former smokers.24 Schwartz-Arad et al. also found a greater risk of complications and peri-implantis in smokers.33 However, there was not a strict recall schedule in these studies. Swierkot et al. reported that there was no consistent correlation between smoking and survival rates of the implants.27 This confirms other long-term studies with subjects in a regular recall program, showing no obvious differences in the survival rate of implants in smokers and non-smokers.22,26,34-36 Thus, Swierkot et al. described that smoking seems to have no serious influence on peri-implant condition in periodontally treated subjects with implants who were in a strict recall program.27

The recommended recall program protocol is that once these restorations are delivered, the patient must undergo a strict oral hygiene regimen at home and maintain a rigid three-month interval maintenance program. When bleeding on probing and mucositis are detected, home care must be re-enforced, submucosal mechanical plaque control and submucosal application of local antiseptic agents such as iodine, sodium hypochlorite, and chlorhexidine or local delivery of antibiotics should be initiated and a re-evaluation should be carried out after a one- to two-week period. If those steps fail to control mucosal inflammation, bacterial sampling, and systemic antibiotic therapy may be indicated when putative periodontal pathogens and/or enteric rods are detected, especially if peri-implant bone loss may be evident. Surgical mucosal contouring and submucosal debridement may also be considered to manage persistent peri-implant mucositis.37

CONCLUSION

The survival rates of the superstructures were 95.9-100% in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis. Marginal bone loss around implants in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis as compared with implants in healthy patients or chronic periodontitis patients was not significantly greater in short-term studies but was significantly greater in long-term studies. In short term studies, the success rates of implants were between 97.4% and 100% in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis, and there were no significant differences for the implant success between the three groups except one study which involved smokers and patients with systemic diseases. The survival rates of implants were between 83.3% and 96% in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis in long-term studies. Therefore, implant treatment in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis is not contraindicated provided that adequate infection control and an individualized maintenance program are assured.

References

- 1.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Periodontology. Parameter on aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2000;71:867–869. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.5-S.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sachdeo A, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Biofilms in the edentulous oral cavity. J Prosthodont. 2008;17:348–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2008.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Boever AL, De Boever JA. Early colonization of non-submerged dental implants in patients with a history of advanced aggressive periodontitis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2006;17:8–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2005.01175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quirynen M, Vogels R, Peeters W, van Steenberghe D, Naert I, Haffajee A. Dynamics of initial subgingival colonization of 'pristine' peri-implant pockets. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2006;17:25–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2005.01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bullon P, Fioroni M, Goteri G, Rubini C, Battino M. Immunohistochemical analysis of soft tissues in implants with healthy and peri-implantitis condition, and aggressive periodontitis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2004;15:553–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2004.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Weijden GA, van Bemmel KM, Renvert S. Implant therapy in partially edentulous, periodontally compromised patients: a review. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:506–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schou S, Holmstrup P, Worthington HV, Esposito M. Outcome of implant therapy in patients with previous tooth loss due to periodontitis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2006;17:104–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2006.01347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klokkevold PR, Han TJ. How do smoking, diabetes, and periodontitis affect outcomes of implant treatment? Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2007;22:173–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karoussis IK, Kotsovilis S, Fourmousis I. A comprehensive and critical review of dental implant prognosis in periodontally compromised partially edentulous patients. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2007;18:669–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schou S. Implant treatment in periodontitis-susceptible patients: a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35:9–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2007.01830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Zahrani MS. Implant therapy in aggressive periodontitis patients: a systematic review and clinical implications. Quintessence Int. 2008;39:211–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yalçin S, Yalçin F, Günay Y, Bellaz B, Onal S, Firatli E. Treatment of aggressive periodontitis by osseointegrated dental implants. A case report. J Periodontol. 2001;72:411–416. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mengel R, Lehmann KM, Metke W, Wolf J, Flores-de-Jacoby L. A telescopic crown concept for the restoration of partially edentulous patients with aggressive generalized periodontitis: two case reports. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2002;22:129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu AY, Chee W. Implant-supported reconstruction in a patient with generalized aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2007;78:777–782. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann O, Beaumont C, Zafiropoulos GG. Combined periodontal and implant treatment of a case of aggressive periodontitis. J Oral Implantol. 2007;33:288–292. doi: 10.1563/1548-1336(2007)33[288:CPAITO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong JS, Yeo IS, Kim SH, Lee JB, Han JS, Yang JH. Implants and all-ceramic restorations in a patient treated for aggressive periodontitis: a case report. J Adv Prosthodont. 2010;2:97–101. doi: 10.4047/jap.2010.2.3.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huh YH, Shin HJ, Kim DG, Park CJ, Cho LR. Full mouth fixed implant rehabilitation in a patient with generalized aggressive periodontitis. J Adv Prosthodont. 2010;2:154–159. doi: 10.4047/jap.2010.2.4.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bidra AS, Shaqman M. Treatment planning and sequence for implant therapy in a young adult with generalized aggressive periodontitis. J Oral Implantol. 2012;38:405–415. doi: 10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-10-00118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kehl M, Swierkot K, Mengel R. Three-dimensional measurement of bone loss at implants in patients with periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2011;82:689–699. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mengel R, Flores-de-Jacoby L. Implants in patients treated for generalized aggressive and chronic periodontitis: a 3-year prospective longitudinal study. J Periodontol. 2005;76:534–543. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mengel R, Flores-de-Jacoby L. Implants in regenerated bone in patients treated for generalized aggressive periodontitis: a prospective longitudinal study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2005;25:331–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mengel R, Kreuzer G, Lehmann KM, Flores-de-Jacoby L. A telescopic crown concept for the restoration of partially edentulous patients with aggressive generalized periodontitis: a 3-year prospective longitudinal study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2007;27:231–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Boever AL, Quirynen M, Coucke W, Theuniers G, De Boever JA. Clinical and radiographic study of implant treatment outcome in periodontally susceptible and non-susceptible patients: a prospective long-term study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009;20:1341–1350. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mengel R, Schröder T, Flores-de-Jacoby L. Osseointegrated implants in patients treated for generalized chronic periodontitis and generalized aggressive periodontitis: 3- and 5-year results of a prospective long-term study. J Periodontol. 2001;72:977–989. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.8.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mengel R, Behle M, Flores-de-Jacoby L. Osseointegrated implants in subjects treated for generalized aggressive periodontitis: 10-year results of a prospective, long-term cohort study. J Periodontol. 2007;78:2229–2237. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.070201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swierkot K, Lottholz P, Flores-de-Jacoby L, Mengel R. Mucositis, peri-implantitis, implant success, and survival of implants in patients with treated generalized aggressive periodontitis: 3- to 16-year results of a prospective long-term cohort study. J Periodontol. 2012;83:1213–1225. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albrektsson T, Zarb G, Worthington P, Eriksson AR. The long-term efficacy of currently used dental implants: a review and proposed criteria of success. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1986;1:11–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bain CA, Moy PK. The association between the failure of dental implants and cigarette smoking. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1993;8:609–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Bruyn H, Collaert B. The effect of smoking on early implant failure. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1994;5:260–264. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1994.050410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strietzel FP, Reichart PA, Kale A, Kulkarni M, Wegner B, Küchler I. Smoking interferes with the prognosis of dental implant treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:523–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindquist LW, Carlsson GE, Jemt T. Association between marginal bone loss around osseointegrated mandibular implants and smoking habits: a 10-year follow-up study. J Dent Res. 1997;76:1667–1674. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760100801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwartz-Arad D, Samet N, Samet N, Mamlider A. Smoking and complications of endosseous dental implants. J Periodontol. 2002;73:153–157. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karoussis IK, Salvi GE, Heitz-Mayfield LJ, Brägger U, Hämmerle CH, Lang NP. Long-term implant prognosis in patients with and without a history of chronic periodontitis: a 10-year prospective cohort study of the ITI Dental Implant System. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2003;14:329–339. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.000.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roos-Jansåker AM, Renvert H, Lindahl C, Renvert S. Nine- to fourteen-year follow-up of implant treatment. Part III: factors associated with peri-implant lesions. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:296–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bain CA, Weng D, Meltzer A, Kohles SS, Stach RM. A meta-analysis evaluating the risk for implant failure in patients who smoke. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2002;23:695–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chee W. Peri-implant management of patients with aggressive periodontitis. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2011;39:416–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]