Abstract

Visual-to-auditory sensory-substitution devices allow users to perceive a visual image using sound. Using a motor-learning task, we found that new sensory-motor information was generalized across sensory modalities. We imposed a rotation when participants reached to visual targets, and found that not only seeing, but also hearing the location of targets via a sensory-substitution device resulted in biased movements. When the rotation was removed, aftereffects occurred whether the location of targets was seen or heard. Our findings demonstrate that sensory-motor learning was not sensory-modality-specific. We conclude that novel sensory-motor information can be transferred between sensory modalities.

Visual sensory substitution devices (SSDs) convey visual information by an alternative sense (e.g., touch or sound). They have been developed to assist blind and visually impaired individuals to perceive and interact with their environment1,2,3,4,5 (see fig 1), and are becoming increasingly popular in recent years. However, the key question of how perception of the environment via the SSD is combined with any residual vision has remained unanswered. The answer to this question would illuminate fundamental aspects of how our brain processes sensory information for the generation of movements. More generally, we are interested in exploring the sensory-modality dependence or independence of spatial representation. To the best of our knowledge, the ability to share shape and location information between direct vision, and the “visual” imagery created by the visual-to-auditory SSD, has never been studied. We ask whether the integration of sensory information into a coherent percept of the world, used to generate movements, is dependent on the type of sensory input received. To that end, we designed a task where participants implicitly learned new sensory-motor correspondence – i.e., they had to perform different movements to receive the same sensory feedback – using one sense, and tested whether the new mapping would be applied when performing movements to targets presented by another sense. We then tested whether this new mapping persisted when the original sensory-motor correspondence was restored.

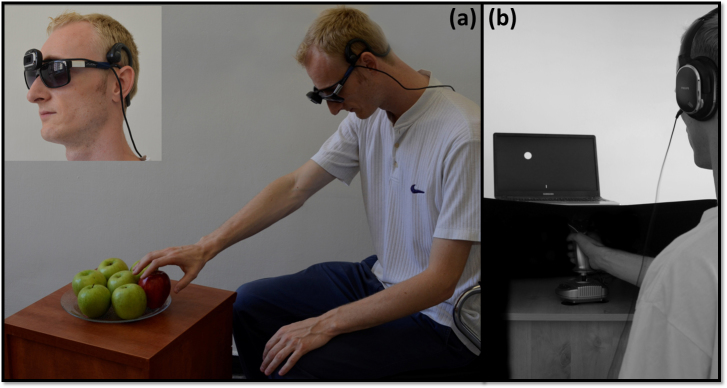

Figure 1. The EyeMusic.

(a) An illustration of the EyeMusic SSD. The user is wearing a mobile camera on a pair of glasses, which captures the colorful image in front of him. The EyeMusic algorithm translates the image into a combination of musical notes, conveyed via scalp headphones. The sounds enable the user to reconstruct the original image, and, based on this information, perform the appropriate motor action. Inset: a close up of the EyeMusic head gear. (b) An illustration of the experimental setup. The participant is seated in front of a table, controlling the joystick with his right hand. His hand and forearm are occluded from view, and he sees the target and cursor location on the computer screen (on VIS trials). Via headphones, he hears the soundscapes marking the target location (on SSD trials).

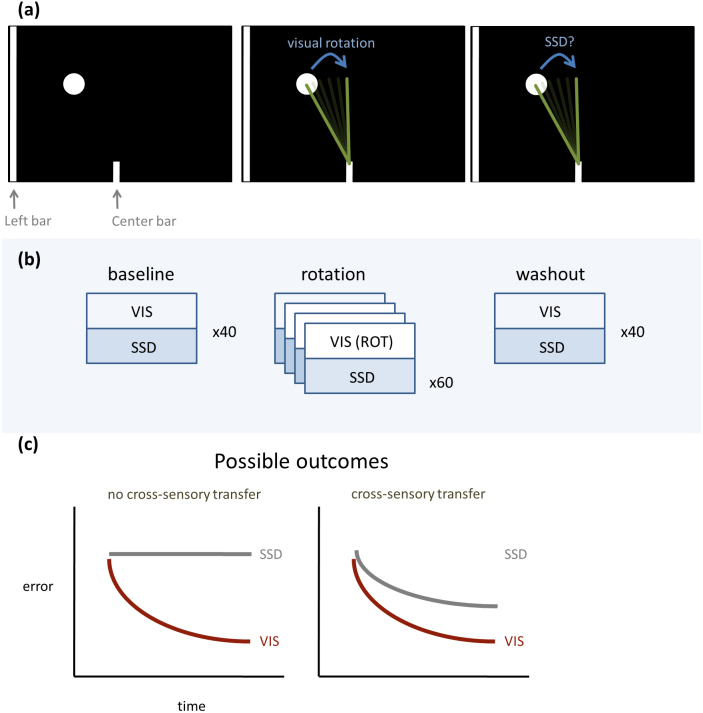

We tested sighted individuals on a visuomotor rotation task. The participants performed reaching movements with a joystick to targets in space (Fig 2a). They were not made aware at any point in the experiment that changes were applied to the required task. They were informed about the location of the targets either visually (VIS) or using a visual-to-auditory SSD. During SSD trials, information was given only regarding the location of the target. During VIS trials, cursor and endpoint (final hand location) information was also available. SSD and VIS trials were interleaved. After a baseline block (Fig 2b), a visuomotor rotation (see Methods) was applied to the visual trials, such that participants had to alter their hand movements in order to reach the targets. It is well established that participants are able to learn to perform a different movement without awareness of the change. We tested whether this imposed rotation during the visual trials would affect movements to targets presented via the SSD. There were two possible outcomes to this experiment (see fig 2c). If there were no transfer of the adaptation to the rotation from the visual to the auditory trials (fig 2c, left panel), then the error of the SSD-guided movements would remain constant throughout the rotation trials. If, however, there were cross-sensory transfer of the adaptation (fig 2c, right panel), the decrease in error with respect to the rotated target would drop over time under both conditions. A priori, there is no reason to assume that learning of the rotation that is introduced via the visual sense would transfer to the execution of movements made to targets presented by the SSD. The results we report here demonstrate that, in parallel to learning the feedback-based visuomotor rotation, a parallel application of the learning occurred in the trials where the targets were presented via the SSD. When we removed the rotation, we observed aftereffects whether the location of targets was seen or heard.

Figure 2. Experimental design.

(a) Illustration of the left target which participants had to identify (Training session) or reach for (Test session); The left (long) and the center (short) vertical bars were used to cue the participants on the start and midpoint of the scan (left panel); a schematic of the anticipated rotation during the visual rotation is shown in the middle panel, and a schematic of a possible outcome with the SSD shown on the right. The green lines represent the expected hand motion of the participants. (b) The experimental protocol: 40 trials during the baseline block, followed by 4 blocks of rotation with 60 trials each, and a single washout block with 40 trials. Between each two blocks, a 40-sec break was given, along with an on-screen report of the participant's average cumulative score. (c) A schematic of the two possible outcomes of the experiment during the rotation: if there is no cross-sensory transfer (left panel), the error on the VIS trials will drop, while the error in the SSD trials will remain constant; if, however, there is cross-sensory transfer (right panel), the drop in error on VIS trials will be accompanied by a drop in error on SSD trials.

Our findings have important implications in the field of rehabilitation. They suggest that blind individuals who undergo visual prosthesis implantation, as well as visually impaired individuals with residual vision, would be able to intuitively integrate spatial information arriving from the visual system, with that from the SSD to create the most complete representation of their surroundings.

Results

Training session

The training session lasted 2.3 min on average (the shortest session lasted 1.8 min, and the longest lasted 3.1 min).

Each stimulus was scanned, on average, for 5.0 sec (minimum scan time was 3.8 sec, maximum scan time was 7.1 sec).

Participants were on average 98% correct in their responses during the training session. The lowest score was 88% correct and 13 of the 18 participants were 100% correct.

Test session

Nine out of the 18 participants (50%) reported they noticed some difference among the blocks, which they attributed to factors such as loss of focus, discomfort, etc. None reported they were aware of a rotation.

Time

Considering all 320 trials per individual, the time elapsed between the start of a trial and the start of the following trial was on average 6.0±3.0 sec (mean±SD) for the SSD trials, and 4.7±6.7 sec for the VIS trials.

Directional error

Rotation

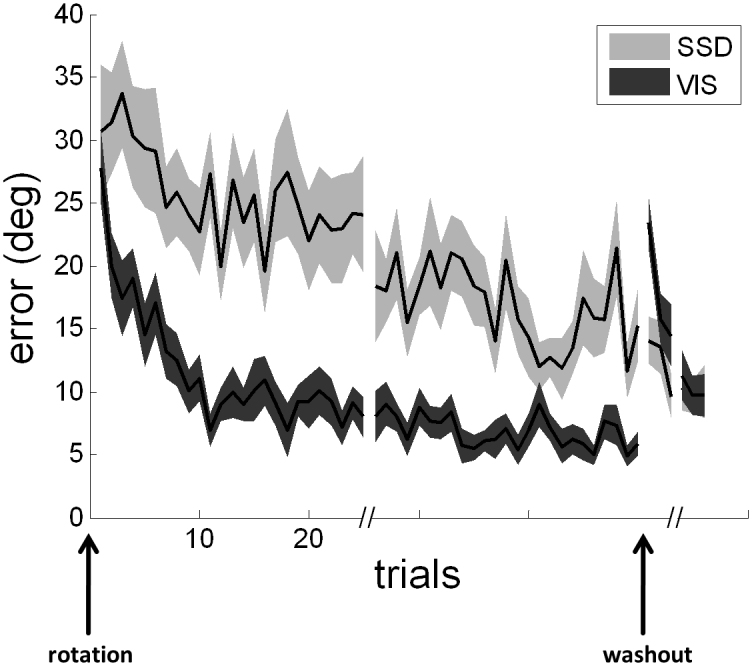

As expected, upon the introduction of the rotation in the visual trials, the directional error was approximately 30 degrees (see Fig. 3). In accordance with previous literature, there was a gradual decrease in error across trials with visual feedback. We found a significant difference between the first and the last rotation trials when the feedback was visual (paired t-test, p<1x10−5). Surprisingly, the learning during the visual trials was accompanied by a parallel drop in error during the SSD trials, despite the fact that no feedback was provided during these trials, and therefore there was no indication that the rotation was applied during these trials as well. We found a significant difference between the first and the last rotation trials when the feedback was given via the EyeMusic SSD (paired t-test, p = 0.012). As evident from Fig 3, the adaptation during the VIS trials and the transfer of the learning from the VIS to the SSD trials did not happen sequentially. That is, the participants began to rotate their SSD-guided movements shortly after the onset of visual rotation, before the visual learning curve plateaued.

Figure 3. Directional error on rotation and washout trials, ±standard error.

An initial error of approx. 30° upon introduction of the rotation is reduced during the rotation blocks on both vision and SSD trials. Black arrows indicate the onset and offset of rotation.

Washout

After the rotation was removed, aftereffects were present during both types of trials (VIS/SSD), as evidenced by directional error greater than zero (baseline) at the end of the washout block (p< 1e-4, VIS; p< 1e-3, SSD; see Fig 3).

Discussion

We have demonstrated that participants who were exposed to a visuomotor rotation also rotated their movements when performing auditorily guided movements, via sensory substitution, despite no explicit feedback indicating this transfer was desired or appropriate. None of the participants reported explicit awareness of the rotation under the visual condition, indicating that the cross- sensory transfer was not done consciously. Subsequently, when the applied rotation was removed, participants showed after effects on both types of trials: auditory and visual.

These findings do not preclude the possibility that the participants, rather than using auditory information to directly control movement, “translated” it into a visual image of the target location, and acted based on this image3. Indeed, a ‘visual'-like representation is the ultimate goal of SSDs for the blind. Moreover, what is often referred to as “visual imagery” may in fact be an abstract, sensory-modality-independent spatial representation (see also 10).

The various senses, including vision, audition and touch, often combine to give us a sense of our surroundings. When congruent, the combination of multisensory information may result in a reduced reaction time11,12. We are interested in the ability to share shape and location information between direct vision, and the “visual” imagery created by the visual-to-auditory SSD. It has been shown that participants are able to match between shapes sounded out by a visual-to-auditory SSD and touched ones10, indicating that shape information was shared between the auditory (SSD) and touch senses. In the current study we show that new spatial information about the world (in this case, rotation) that is supplied only by visual input is used to act in the world when information is supplied by audition (via sensory substitution) only. We have shown that the adaptation transfers within a few trials only, and that aftereffects are observed regardless of the sensory modality used to present the targets. These results give strong support to the hypothesis that neural representations of motor control are sensory-modality-independent.

Even within the visual sense, transfer of new sensory-motor information is not obvious, and stimulus-generalization13 is considered very limited in its extent. For example, when humans9 and monkeys14 adapt to a new visuomotor rotation rule by training in a specific direction, movements to targets located more than 45 degrees away from the trained target are not affected. Our findings, indicating strong cross- sensory transfer of new sensory-motor information, can be explained by the existence of an action-dependent component of learning15. In addition to learning to change their response to the visual target, the participants might have learned to predict the consequences of performing hand movements in the learned direction. In turn, whether the location of the target was seen or heard, the subjects performed similar movements as a response.

This is the first demonstration, to the best of our knowledge, of transfer between the visual sense and a visual-to-auditory SSD. We show clear evidence that in adult individuals – previously naïve to sensory substitution which uses audition to represent topographical vision – there was immediate unconscious transfer of spatial information between the senses. These findings pave the way for development of hybrid aids for the Blind, which combine input from low-resolution visual prostheses – used for example to detect the silhouette of a person – and from a visual-to-auditory SSD used to perceive the facial expression of that individual (for a video demonstration of the latter, see supplementary materials in16).

Methods

Participants

18 young adult participants without any known neurological disorders or tremor were tested (age range: 18–30; 11 females; 7 males). All participants were right handed, as determined by the handedness-dominance questionnaire, had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and no hearing impairment. They were naïve to the experimental procedure and to the use of the SSD. All participants gave their informed consent to participate. The protocol was approved by the Hebrew University's committee on human research.

Equipment

The seated participants used their right hand to control a joystick (Logitech, extreme 3D Pro). A computer screen was used to provide visual feedback during the experiment. The joystick was fixed in a single location and orientation, and an opaque cover was placed parallel to the table and above the apparatus such that during the experiment, the joystick, as well as the participant's hand and forearm were occluded from view. Participants were asked to move the joystick in all possible directions until they learned to control it. The height of the chair and its distance from the desk were adjusted before the experiment initiation and then fixed in the final location. All participants reported they were comfortably seated and able to move their arm freely prior to experiment initiation.

Auditory stimuli were heard using headphones and were produced using the visual-to-auditory sensory substitution device the EyeMusic. This device transforms visual images into “soundscapes” that preserve shape, location and color information using sound3. The EyeMusic represents high locations on an image as high-pitched musical notes on a pentatonic scale, and low vertical locations as low-pitched musical notes on a pentatonic scale. It conveys color information by using different musical instruments for each of the five colors: white, blue, red, green, yellow; Black is represented by silence. The EyeMusic currently employs a resolution of 24x40 pixels.

Protocol

Training session

During a short training session, participants were introduced to the EyeMusic SSD, and were taught to identify the location of an auditory target located either on the left or on the right side of the screen. The target was a white circular disk, 2.5 cm in diameter, located either at 60 deg or at 120 deg from the horizontal (i.e., ±30 deg with respect to a virtual vertical line bisecting the screen). Two bars, of different vertical lengths, were located on the left and at the center of the screen and were used as reference points for the location of the left most part and the center of the screen (see Fig 2a).

A short break followed the training session, during which the task for the Test session was explained.

Test session

Participants used a joystick to control a screen cursor. They were asked to move the joystick to reach a circular target located ±30 deg either on the left or on the right side of a virtual vertical line bisecting the screen. The targets were the same as those presented to the participants during the training session. The target was presented either visually (VIS) or by an EyeMusic soundscape (SSD). Real-time cursor information was provided during the VIS trials only. The targets were positioned 35 mm away from the starting location, at the bottom-center of the screen (located at the same position as the short center bar, see Fig 2a).

The experimental protocol consisted of three main parts: baseline, rotation and wash-out (see Fig 2b, and Supplementary Video S1). Participants were not made aware that there was any change in the required task during the entirety of the experiment. Participants performed a series of six blocks, where blocks 1 and 6 (baseline and washout, respectively, consisting of 40 trials each) were control blocks in which no perturbation occurred while blocks 2–5 were perturbation blocks (consisting of 60 trials each, for a total of 240 perturbation trials). During the rotation blocks visuomotor rotation was applied to all VIS trials. This transformation rotated the location of the screen cursor by 30deg either clockwise (CW, for 10 participants) or counter-clockwise (CCW, for 8 participants) with respect to a vertical line traversing the starting location. As a result, a movement towards the target located at 120 deg under a CCW rotation would position the cursor at 150 deg instead. With practice, participants implicitly learn that in order to see the cursor reach the target visually presented at 120 deg, they need to aim their hand movements at 90 deg from the horizontal. Similarly, under a CW rotation, in order for the cursor to reach the target visually presented at 60 deg, hand movements need to be aimed at 90 deg from the horizontal (for an illustration, see Supplementary Video S1). Sensory modality (VIS/SSD) was alternated on each trial, so that no two consecutive trials were of the same sensory modality.

Participants were semi-randomly assigned to one of four possible sequences of target locations. In all four sequences, the order of appearance of the right and the left targets was semi-randomized, such that in total there was an equal number of each. The number of trials per each direction per condition (VIS/SSD) across the four sequences ranged between 53 and 67 in the rotation blocks, and between 8 and 12 in the washout block.

Participants initiated each trial by pressing a button on the joystick with the right index finger. After a 0.4 sec delay, the target was presented, and participants were required to initiate the reaching movement towards the target within 4 secs. However, once movement was initiated (as defined by moving a distance greater than 10 mm from the starting point), participants had 750 msec to complete the reach. They were instructed not to perform any corrective movements. At the end of the trial the endpoint reached by the participants was presented –only during the VIS trials – as a blue circle, the same size as the target. During the SSD trials information was given only as to the location of the target and the marking bars. No information regarding cursor or final position location was given. To clear the screen for the next trial, participants pressed the joystick button once again.

During VIS trials only, a score was shown on the screen at the end of each trial based on final position accuracy. A final error < = 4 mm was awarded 10 points, an error greater than 4 mm and < = 8 mm was awarded three points, an error greater than 8 mm and < = 12 mm was awarded one point, and a final position error greater than 12 mm was awarded zero points6. During the SSD trials, a score was calculated, but not reported to the participants.

At the end of each block was a 40-sec break, during which participants were presented with their cumulative average score, which included the scores obtained on the VIS and the SSD trials. They were told that beyond the basic compensation for participation in the experiment, they will receive a bonus for high scores.

Data analysis

In order to minimize the effect of different wrist dynamics on the results, we analyzed movements performed to targets located within 30 degrees of the vertical, such that both rotation movements, whether performed under CW or CCW rotation, were directed at a target 90 deg from the horizontal. We could thus collapse the data from both rotations. The range of analyzed movements was chosen so that they were within the range of most movements performed as activities of daily living (ADL; see7).

Trials in which participants did not move at all, or made movements that were shorter than 10 mm were excluded from the analysis. This was the case in 1.1% of the trials (66 out of 5760 trials: 320 trials per participant × 18 participants).

Position and velocity traces were filtered using a first-order Butterworth filter (cutoff 20 Hz).

Directional error

Movement angle was calculated at the time the hand trajectory reached its peak speed8,9, to capture the intended direction during the feedforward part of the movement. Error in degrees was calculated as the difference between the angle of the hand trajectory and the angle at which the target was located9.

As we were interested in the change in movement angle in response to the imposed rotation, as opposed to absolute angle, we subtracted the average baseline angle from the angles in the rotation and the washout blocks for each participant, thereby eliminating individual biases8. The absolute value of the relative error was calculated, so that it can be averaged across participants. Error during the rotation blocks was calculated with respect to the location of the rotated target, for both feedback types.

To equate the number of trials analyzed across participants in each condition (VIS/SSD), we report the results for the rotation blocks from 100 out of the approximately 120 trials per participant in the relevant direction (leftward movements under a CW rotation, and rightward movements under a CCW rotation; 60 trials per sensory modality). We took the first 25 and the last 25 completed trials in the rotation trials in each sensory modality8. Similarly, in the washout block, we report the results from 12 out of the approximately 20 trials per participant in the relevant direction (right/left), per sensory modality (VIS/SSD).

Statistical analysis

We performed within-subject analysis comparing the first and last rotation trials, and employed a paired t-test, to eliminate individual bias. Similarly, we compared the last washout trial to zero (baseline) using a t-test. Normal distribution of the data was confirmed using normal probability plots.

Author Contributions

A.A. supervised the project; S.L., I.N. and E.V. designed the experiment; R.A. conducted the experiment; S.L. analyzed the data; S.A., S.M. and A.A. developed the device; S.L. and I.N. wrote the paper; E.V. and A.A. critically reviewed the paper and provided the funding.

Supplementary Material

Experimental setup and procedure illustration

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank M. Dupliy for his help in creating the illustrations in Fig 1. This work was supported by a European Research Council grant to A.A. (grant number 310809); The Charitable Gatsby Foundation; The James S. McDonnell Foundation scholar award (to AA; grant number 220020284); The Israel Science Foundation (grant number ISF 1684/08); The Edmond and Lily Safra Center for Brain Sciences (ELSC) Vision center grant (to AA) and an ELSC fellowship (to SL); SA was supported by a scholarship from the Israeli Ministry of Science.

References

- Bach-Y-Rita P., Collins C. C., Saunders F. A., White B. & Scadden L. Vision substitution by tactile image projection. Nature 221, 963–964 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C. C. Tactile television-mechanical and electrical image projection. IEEE T Man Machine 11, 65–71 (1970). [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Tzedek S., Hanassy S., Abboud S., S M. & Amedi A. Fast, accurate reaching movements with a visual-to-auditory sensory substitution device. Restor Neurol Neuros 30, 313–323 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer P. B. L. An experimental system for auditory image representations. IEEE Bio-Med Eng 39, 112–121 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amedi A., Stern W. M., Camprodon J. A., Bermpohl F., Merabet L., Rotman S., Hemond C., Meijer P. & Pascual-Leone A. Shape conveyed by visual-to-auditory sensory substitution activates the lateral occipital complex. Nat Neurosci 10, 687–689 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabbott B. A. & Sainburg R. L. Learning a visuomotor rotation: simultaneous visual and proprioceptive information is crucial for visuomotor remapping. Exp Brain Res 203, 75–87 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu J., Cooney Iii W. P., Askew L. J., An K. N. & Chao E. Functional ranges of motion of the wrist joint. J Hand Surg 16, 409–419 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami T., Hirashima M., Taga G. & Nozaki D. Asymmetric transfer of visuomotor learning between discrete and rhythmic movements. J Neurosci 30, 4515–4521 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakauer J. W., Pine Z. M., Ghilardi M. F. & Ghez C. Learning of visuomotor transformations for vectorial planning of reaching trajectories. J Neurosci 20, 8916–8924 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. K. & Zatorre R. J. Can you hear shapes you touch? Exp Brain Res 202, 747–754 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molholm S., Ritter W., Murray M. M., Javitt D. C., Schroeder C. E. & Foxe J. J. Multisensory auditory-visual interactions during early sensory processing in humans: a high-density electrical mapping study. Cognitive Brain Res 14, 115–128 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland B. A., Quessy S., Stanford T. R. & Stein B. E. Multisensory integration shortens physiological response latencies. J Neurosci 27, 5879–5884 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman N. & Kalish H. I. Discriminability and stimulus generalization. J Exp Psychol 51, 79–88 (1956). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz R., Boraud T., Natan C., Bergman H. & Vaadia E. Preparatory activity in motor cortex reflects learning of local visuomotor skills. Nat Neurosci 6, 882–890 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick I. & Vaadia E. Just Do It: Action-Dependent Learning Allows Sensory Prediction. PLoS ONE 6, e26020 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striem-Amit E., Guendelman M. & Amedi A. ‘Visual' Acuity of the Congenitally Blind Using Visual-to-Auditory Sensory Substitution. PLoS ONE 7, e33136 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental setup and procedure illustration