Abstract

Epitope tagging permits the detection of proteins when protein-specific antibodies are not available. However, the epitope tag can reduce the function of the tagged protein. Here we describe a cassette that can be used to introduce an eight amino acid flexible linker between multiple Myc epitopes and the open reading frame of a given gene. We show that inserting the linker improves the in vivo ability of the telomerase subunits Est2p and Est1p to maintain telomere length. The methods used here are generally applicable to improve the function of tagged proteins in both Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe.

Keywords: epitope tag, protein linker, in vivo function, telomere, yeast telomerase

Introduction

Antibodies are probably the most commonly used reagent to monitor the behaviour of proteins. However, in some cases, antibodies are not available for a given protein, or the protein is of such low abundance that it is difficult to detect in whole cell extracts using conventional anti-sera. A common solution is to epitope-tag the protein and use an antibody against the epitope to detect it. A serious concern with epitope tagging, however, is that the tag may affect protein function. At least in yeast, where genetic assays can be used to monitor gene function, increasing the number of epitopes on a tagged gene improves sensitivity but often has even more deleterious effects on protein function than insertion of a single epitope.

Flexible protein linkers have been used to increase the accessibility of an epitope to antibodies (Grote et al., 1995) or to improve protein folding (Borjigin and Nathans, 1994). Linkers have also been used in protein purification vectors, e.g. TAP tags (Rigaut et al., 1999) or the pMAL vector series (Maina et al., 1988), but in these instances the linkers are recognition sites for various proteolytic enzymes to remove the tag from the protein being purified. There has been no analysis of how flexible linkers affect the in vivo function of epitope-tagged proteins in yeast. Here we describe a cassette that can be used to insert a flexible linker between the open reading frame of any yeast gene and nine Myc epitopes. We show that the presence of this flexible linker improves the in vivo function of several epitope-tagged proteins involved in telomere maintenance.

Materials and methods

Strains and plasmids

Strains were derivatives of YPH499 (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989; MAT a ura3-52 lys2-801 ade2-101 trp1-Δ63 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1), W303 (Thomas and Rothstein, 1989; MAT a ade2-1 trp1-1 ura3-1 leu2-3,112 his3-11,15 can1-100 ) or VPS106 (Schulz and Zakian, 1994; MAT a ade2 ade3 leu2-3 112 ura3 Δ trp1 Δ lys2-801 can1 ) (Table 1). Gene modifications were confirmed by Southern blotting for the relevant marker and for telomere length. In each case, the Myc-tagged protein was the only form of the protein in the cell. Except for the Rrm3p-G8-Myc, Myc-tagged proteins were expressed under the control of their endogenous promoters from their normal chromosomal loci. Rrm3p-G8-Myc was expressed under the control of the RRM3 promoter from a plasmid (Table 2) in a rrm3 Δ strain.

Table 1.

S. cerevisiae strains used

| Strain | Genotype | Figure | Reference/source |

|---|---|---|---|

| YPH499 | MATa ura3-52 lys2-801 ade2-101 trp1-Δ63 his3-Δ 200 leu2-Δ1 | (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989) | |

| YPH499 UT | VII-L::URA3 | 2, 3 | (Tsukamoto et al., 2001; Gottschling et al., 1990) |

| YPH499 UT Myc-Est2 | VII-L::URA3 Myc9 or 18-Est2::TRP1 | 2, 3 | A. K. P. Taggart |

| YPH499 UT Myc-G5-Est2 | VII-L::URA3 Myc9-G5-Est2::TRP1 | 2 | A. K. P. Taggart |

| YPH499 UT Myc-G8-Est2 | VII-L::URA3 Myc9-G8-Est2::TRP1 | 2, 3 | A. K. P. Taggart |

| YPH499 UT Est2-G2AG2-Myc | VII-L::URA3 Est2-G2AG2-Myc9::TRP1 | 2 | A. K. P. Taggart |

| W303 | MATa ade2-1 trp1-1 ura3-1 leu2-3,112 his3-11,15 can1-100 | 2 | (Thomas and Rothstein, 1989) |

| W303 Est1-Myc | Est1-Myc18::TRP1 | 2 | C. T. Tuzon |

| W303 Est1-G8-Myc | Est1-G8-Myc18::TRP1 | 2 | C. T. Tuzon |

| YPH499 UT Myc-Est2 yku70Δ | VII-L::URA3 Myc18-Est2::TRP1 yku70Δ::HIS3 | 3 | A. K. P. Taggart |

| YPH499 UT Myc-G8-Est2 yku70Δ | VII-L::URA3 Myc9-G8-Est2::TRP1 yku70Δ::HIS3 | 3 | T. S. Fisher |

| YPH499 UT est1-60 | VII-L::URA3 est1-60::TRP1 | 3 | (Pennock et al., 2001) |

| VPS106 | MATa ade2 ade3 leu2-3 112 ura3Δ trp1Δ lys2-801 can1 | (Schulz and Zakian, 1994) | |

| VPS106 UT rrm3Δ | VII-L::URA3 rrm3Δ::TRP1 | 4 | (Bessler and Zakian, 2004) |

Table 2.

Plasmids used (Figure 4)

| Name | Insert | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| YCplac111 | CEN4 ARS1 LEU2 | (Gietz and Sugino, 1988) |

| YCplac111-Rrm3p (pJB5) | RRM3 | (Bessler and Zakian, 2004; Ivessa et al., 2002) |

| YCplac111-Rrm3p-G8-Myc9 (pJB108) | RRM3-G8-Myc9 | (Bessler and Zakian, 2004) |

Epitope tagging

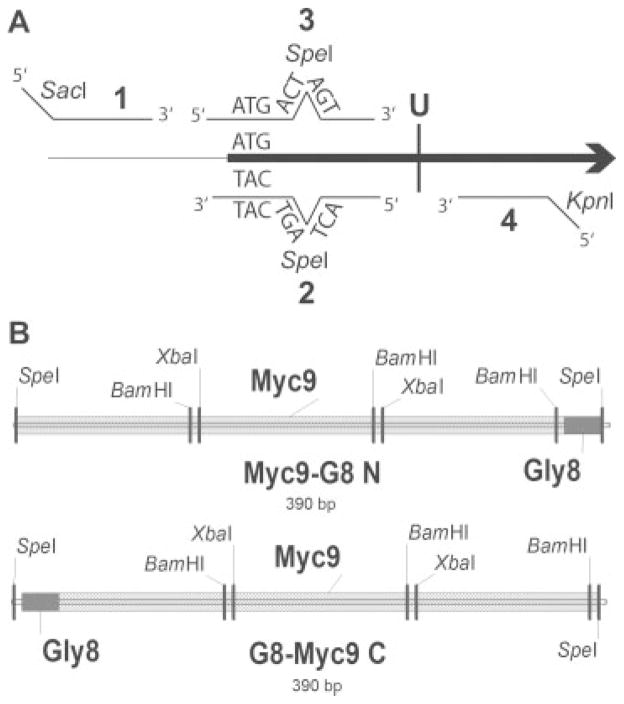

To target the tag to the endogenous locus, we cloned either the 5′ or the 3′ end of the gene to be tagged into a selectable plasmid; typically we use TRP1-marked pRS304 (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989). The amount of sequence that was cloned into the tagging plasmid was determined by how much of the gene sequence was required to ensure that it included a unique restriction enzyme site that could be used to linearize the tagging plasmid prior to introducing it into the cell by transformation. In addition, a few hundred bp upstream or downstream of the partial open reading frame were included to provide sufficient sequence homology to target its integration at the endogenous locus. Since we removed the multiple cloning site of pRS304 (and the unique SpeI site therein) by digestion with SacI and KpnI, we were able to engineer a unique SpeI site, either immediately following the start codon (see Figure 1A for the two-step PCR cloning strategy) or immediately preceding the stop codon, to provide a ligation point for the insertion of the desired epitope fragment.

Figure 1.

PCR strategy and G8-linkered DNA cassettes for cloning. (A) The strategy for two-step PCR cloning of the 5′ end of a gene of interest (not drawn to scale). The first step is two separate PCR reactions that use: (a) primers 1 and 2 and (b) primers 3 and 4, with genomic DNA as a template. Primers 2 and 3 have six extra bases to insert a SpeI site immediately following the start codon. The second step uses primers 1 and 4 with the products of the both of the first step reactions as template. Primers 1 and 4 have extra sequence on their 5′ tails to generate SacI and KpnI restriction sites for annealing into SacI/KpnI-digested pRS304. The position of the restriction site that is unique to the gene of interest once cloned into pRS304 is indicated by U. A similar strategy can be used to clone and insert a SpeI site immediately preceding the stop codon at the 3′ end of a gene of interest. (B) The DNA fragments released from the Myc-containing vectors pBSMyc9-G8 N or pBSG8-Myc9 C by SpeI digestion (drawn to scale). At the top is the fragment for adding Myc9-G8 to the N-terminus of a protein; at the bottom is the fragment for adding G8-Myc9 to the C-terminus of a protein. The liberated cassettes are ligated into the SpeI site engineered into the pRS304 + cloned gene of interest tagging plasmid. The hatched area indicates the Myc9 fragment, which is three repeats of Myc3 separated by tandem BamHI and XbaI restriction sites; the grey box indicates the G8 linker sequence

The original Myc9 cassette was a gift from K. Nasmyth; in some cases we used a Myc18 cassette which we cloned from a spontaneous in vivo duplication event (Taggart et al., 2002). The linkers used to separate the Myc epitopes from the protein being tagged, which included G5, G8 and G2AG2, were engineered using oligonucleotide synthesis of the two Gly codons most commonly used by yeast and ligated into the Myc-containing plasmid to generate pBSMyc9-G8 N or pBSG8-Myc9 C. While this ligation would normally duplicate the SpeI site to flank the insertion, the ligated tails were designed to preserve the external SpeI site while eliminating the internal SpeI site. For tagging the N-terminus of a protein, the linker sequence was positioned 3′ of the Myc epitopes (as Myc9-G8 N; Figure 1B, top); for tagging the C-terminus of a protein, the linker sequence was positioned 5′ of the Myc epitopes (as G8-Myc9 C; Figure 1B, bottom). The desired Myc + linker cassette was then liberated from the Myc plasmid (pBSMyc9-G8 N or pBSG8-Myc9 C, respectively) by SpeI digestion and ligated into the SpeI site engineered into the gene of interest that was previously cloned into the pRS304 tagging plasmid. The resulting plasmid, pRS304 + partial open reading frame + Myc-linker, was then linearized by digestion with the restriction enzyme unique to the open reading frame prior to transformation and selection on Trp− drop-out plates. Integration of the tagging plasmid will generate a partial gene duplication in the yeast genome. If desired, TRP1 counter-selection on 4-fluoroanthranilic acid can be used to select for cells that had lost the partial duplication and retained the epitope tag, as identified by both Southern and Western blotting.

Most of the tagged proteins used in our laboratory are Myc9-tagged. The Myc18 tag has been used to improve the signal : noise ratio in chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments; in such cases, inclusion of the additional 9 Myc epitopes did not compromise telomere length.

Telomere blot analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated using the MasterPure Yeast DNA Purification Kit (Epicentre), digested with PstI and XhoI, separated by electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel, and blotted onto Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham Biosciences). The blot was probed with a either a yeast C1–3A/TG1–3 telomeric DNA probe (prepared by EcoRI digestion of pCT300, releasing ~275 bp TG1–3 in pVZ-1, from K. Runge, R. Wellinger, J. Wright and V.A.Z.) or a URA3 probe labelled by random priming. Blots were exposed to a phosphoimager screen overnight and scanned using a Molecular Dynamics phosphoimager.

Western blot analysis

Whole cell protein extracts were prepared by disrupting cells in equal volumes of CE lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 10% v/v glycerol, 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630 and 1 mM DTT) containing Complete® EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche) and glass beads. Samples were separated on 7.8% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated in a 1 : 1000 dilution of Myc monoclonal primary antibody (BD Biosciences) and then incubated in a 1 : 3000 dilution of goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Bio-Rad). Alternatively, membranes were probed with a 1 : 2000 dilution of a polyclonal Rrm3p antiserum (Ivessa et al., 2000) and then incubated in a 1 : 3000 dilution of goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Bio-Rad). The membranes were developed using an ECL chemiluminescence system (Amersham Biosciences) and exposed to Kodak Biomax XAR autoradiography film.

Results and discussion

Telomerase is a specialized reverse transcriptase that maintains telomeric DNA in most organisms. There are at least three proteins of low abundance that are part of the S. cerevisiae telomerase holoenzyme: Est2p (the catalytic reverse transcriptase) and two accessory proteins, Est1p and Est3p (reviewed in Vega et al., 2003). Loss of any one of these proteins leads to progressive loss of telomeric DNA and to the eventual loss of cell viability, the so-called ever shorter telomere (est) phenotype (Lundblad and Szostak, 1989). We have been studying the cell cycle-regulated association of these proteins with telomeres using chromatin immunoprecipitation (Tsukamoto et al., 2001; Taggart et al., 2002; Fisher et al., 2004). However, these proteins are of such low abundance that inserting one to three Myc or HA epitopes did not allow us to detect the proteins. Therefore, we used standard procedures to fuse 9 or 18 Myc epitopes in-frame to these proteins. Because these proteins are needed to maintain telomeres, Southern blot analysis of telomere length provides a sensitive means to monitor the functions of the tagged proteins. In addition, if the tagged est protein is non-functional, the strain expressing it will have an est phenotype.

Cells of the YPH499 strain background expressing an Est2p that was Myc-tagged at its carboxyl terminus had an est phenotype (A. K. P. Taggart and V.A.Z., unpublished results). Although cells expressing amino-terminally Myc-tagged Est2p do not senesce, telomeres are ~50 bp shorter than the wild-type length of ~300 bp (Taggart et al., 2002; Figure 2). Likewise, telomeres are ~50 bp shorter than wild-type in cells from the TVL268 strain background expressing Est2p tagged at its amino terminus with ProA (Friedman and Cech, 1999). In addition, we were unable to recover strains that express Myc-Est2p in certain mutant backgrounds that were compromised for telomere maintenance (e.g. in strains lacking the heterodimeric Ku complex).

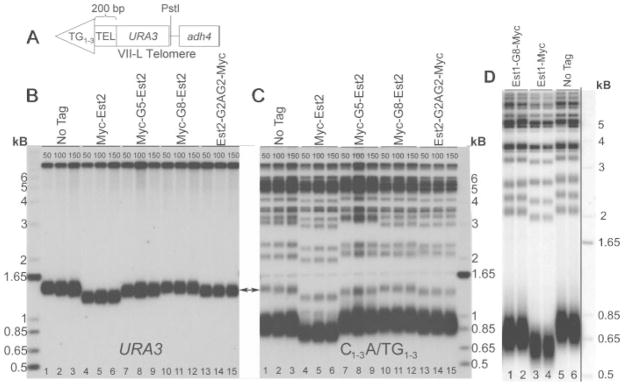

Figure 2.

A flexible linker improves the functionality of Myc-tagged Est2p and Est1p as monitored by effects on telomere length. (A) The modified left telomere of chromosome VII (Gottschling et al., 1990). (B) A Southern blot probed with URA3 to detect the left telomere of chromosome VII (marked by arrow between B and C). The larger fragment results from hybridization with the ura3-52 locus. (C) The same blot stripped and reprobed with a telomeric C1 – 3A/TG1 – 3 probe that detects both telomeric and subtelomeric sequences. Lanes 1–3, DNA from strains that are EST2 (No Tag); lanes 4–6, DNA from cells expressing unlinkered Myc-Est2p (Taggart et al., 2002; Myc-Est2); lanes 7–15, DNA from strains expressing Myc-Est2p (or Est2p-Myc) where the tag is separated from the protein by the indicated linker. In each case, DNA was isolated from transformants at 50, 100 and 150 divisions. (D) A Southern blot probed with a telomeric C1 – 3A/TG1 – 3 probe in yeast expressing Est1p Myc-tagged at its C-terminus in the W303 strain background. Lanes 1–2, DNA from cells expressing Est1p-Gly8-Myc (Est1-G8-Myc); lanes 3–4, DNA from cells expressing unlinkered Est1p-Myc; lanes 5–6, DNA from cells that are EST1 (No Tag). Although Est1p-Myc supports wild-type telomere length in some backgrounds, including YPH499 (Taggart et al., 2002), it does not do so in the W303 strain background

To improve the in vivo function of the epitope-tagged Est2p, we designed three linkers: five tandem glycine residues (called G5); eight tandem glycine residues (G8; see Figure 1); and GlyGlyAlaGlyGly (called G2AG2). The linkers were inserted between the Myc epitopes and the EST2 open reading frame at either the amino or carboxyl terminus of Est2p. By whole-cell lysate Western blot analysis using an anti-Myc antibody, the same levels of Est2p were produced whether or not a linker was used and independent of the identity of the linker (data not shown).

To assess the in vivo function of the tagged Est2p, we compared telomere lengths between untagged, unlinkered and linker-tagged Est2p by monitoring the length of telomere VII-L (Figure 2A; the VII-L telomeric fragment is indicated by an arrow between B and C of Figure 2) as well as that of bulk telomeres (Figure 2C) at 50, 100 and 150 cell divisions after the strains were generated. Telomeres were longer and closer to wild-type in length in the strains with any flexible linker than in cells expressing the unlinkered Myc-Est2p, and telomere length was stably maintained for at least 150 cell generations. Telomeres in cells expressing Myc-G8-Est2 were indistinguishable in length from telomeres in wild-type cells (cf. telomere length in lanes 10–12 with the untagged strain in lanes 1–3). Similar results were seen when the linkers were inserted in between Est2p and the Myc tag at the opposite terminus (data not shown). Considering that telomere length is a very sensitive measure of function, we infer that protein functionality was restored to wild-type or near wild-type levels by the introduction of the flexible linker.

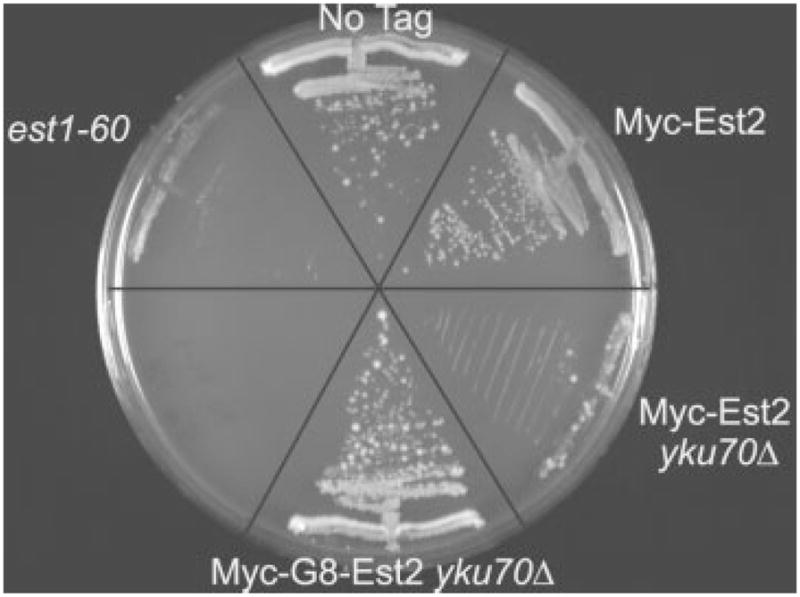

To demonstrate further the improved functionality of Myc-G8-Est2p over Myc-Est2p, we introduced both tagged alleles into a yku70Δ strain (Figure 3). Although a wild-type strain expressing Myc-Est2p does not senesce (Taggart et al., 2002; Figure 3), a yku70Δ strain expressing Myc-Est2p has an est phenotype. In contrast, a yku70Δ strain expressing Myc-G8-Est2p did not display an est phenotype (Figure 3). These data provide additional evidence that the flexible linker improves the functionality of epitope-tagged Est2p.

Figure 3.

yku70Δ cells expressing Myc-G8-Est2p do not senesce. The indicated strains were streaked three consecutive times on minimal media plates; the third restreak is shown. At the upper left are est1-60 cells which demonstrate the classic est phenotype (Pennock et al., 2001). Wild-type cells are at the top (No Tag). To the right are cells expressing unlinkered Myc-Est2p (Taggart et al., 2002) with wild-type yKu70p (Myc-Est2) or no yKu70p (Myc-Est2 yku70Δ). A yku70Δ strain expressing Myc-Est2p has an est phenotype, senescing as quickly as the est1-60 strain. By including a flexible linker between Est2p and the Myc epitopes, YKU70 can now be deleted without causing senescence (Myc-G8-Est2 yku70Δ)

The flexible linker strategy is widely applicable. By the sensitive criterion of telomere length maintenance, insertion of the G8 linker improved the in vivo function of epitope-tagged Est1p (Figure 2D), Est3p (K. M. Daumer and V.A.Z., unpublished results), Stn1p, Ten1p (T.S.F., I. Cheung and V.A.Z., unpublished results), Rif1p and Rif2p (M.S. and V.A.Z., unpublished results). In the case of Est3p, the protein tagged with nine Myc epitopes was non-functional, as cells expressing it had an est phenotype, while the presence of the linker allowed maintenance of near wild-type telomere lengths (data not shown). We have also used the G8 linker cassette to improve the in vivo functionality of Myc-tagged Sz. pombe proteins (C. J. Webb and V.A.Z., unpublished results) and HA-tagged baker’s yeast proteins (T.S.F. and V.A.Z., unpublished results).

The positive effects of the flexible protein linkers are likely due to their allowing for the proper folding of epitope-tagged proteins in vivo. Alternatively, the linker might be susceptible to proteolytic cleavage, which would release untagged, and hence fully functional, protein. However, the Est2p-G8-Myc (Fisher et al., 2004) and Est1p-G8-Myc (C.T.T. and V.A.Z., unpublished results) can immunoprecipitate telomeric DNA as well as, or better than, epitope-tagged versions of the same protein without a linker. Therefore, a large fraction of the telomere-associated forms of these proteins must retain both the linker and the Myc epitopes.

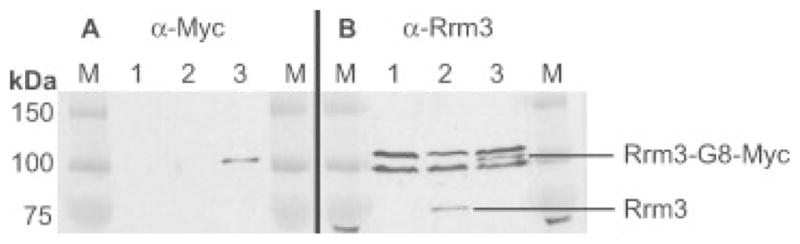

Evidence that the linker is not a site of proteolytic cleavage comes from the analysis of epitope-tagged Rrm3p, a yeast DNA helicase for which anti-serum is available. We generated a strain in which Rrm3p was tagged at its carboxyl terminus to generate Rrm3p-G8-Myc (Bessler and Zakian, 2004). We used Western blot analysis with a polyclonal anti-Rrm3p serum to determine whether Rrm3p-G8-Myc is cleaved in the protein linker (Figure 4B). Whole-cell protein extracts from rrm3Δ (lane 1), untagged Rrm3p (lane 2) and Rrm3p-G8-Myc (lane 3)-expressing strains were separated by PAGE and analysed by Western blotting. When anti-Myc antibody was used to probe the Western blot, a single protein band was detected in the extract from Rrm3p-G8-Myc-expressing cells (Figure 4A, lane 3). The anti-Rrm3p polyclonal serum recognized a single specific band of the appropriate size and of similar abundance in both the untagged strain (Figure 4B, lane 2, 81.6 kDa) and the Rrm3p-G8-Myc-expressing strain (Figure 4B, lane 3, 95.4 kDa), as well as several non-specific bands seen in all strains, including the rrm3Δ strain (Figure 4B, lane 1). The protein detected by the anti-Myc antibody had the same mobility as the protein recognized by the anti-Rrm3p antibody (cf. lanes 3 in Figure 4A, B). Importantly, no untagged Rrm3p was detected in the Rrm3p-G8-Myc extract with the anti-Rrm3p antibody. Thus, there is no evidence, at least for Rrm3p-G8-Myc, that the epitope-tagged protein is cleaved within the flexible protein linker.

Figure 4.

Rrm3p-G8-Myc9 is not cleaved within the flexible linker. All strains are VPS106 rrm3Δ carrying the indicated LEU2-marked plasmid. Extracts were prepared from the indicated strains and separated by SDS–PAGE. (A) Samples are blotted with anti-Myc antibody. (B) Samples are blotted with an anti-Rrm3p N-terminal antibody (Ivessa et al., 2000). Lane 1, empty vector; lane 2, yCPlacIII-Rrm3p; lane 3, yCPlacIII-Rrm3p-G8Myc9. Untagged Rrm3p runs at ~75 kDa; Rrm3p tagged with G8-Myc9 runs at ~100 kDa (between two non-specific bands), as designated on the right. Molecular weight standards (M) with sizes indicated are shown on the left (kDa)

The cassettes described here can be used to insert Myc9-G8 encoding DNA at either the 5′ or 3′ end of any yeast gene of interest, either at its endogenous locus or on an exogenously introduced vector. This system has easily been adapted to fission yeast genes (C. J. Webb and V.A.Z., unpublished results). In principle, the G8 linkers can easily be added to current mammalian epitope-tagging constructs to improve the functionality of tagged proteins in higher eukaryotes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andy Taggart, who began this work, J. B. Bessler for constructing the Rrm3p-G8-Myc9 strain, and K. D. Daumer and C. J. Webb for their comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) post-doctoral fellowship GM068218 (to M.S.), by National Science Foundation post-doctoral fellowship BIO 0610300 (to C.T.T.), by Leukemia and Lymphoma Society post-doctoral fellowship 5091-04 (to T.S.F.) and by NIH grant GM43265 (to V.A.Z).

References

- Bessler JB, Zakian VA. The amino terminus of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA helicase Rrm3p modulates protein function, altering replication and checkpoint activity. Genetics. 2004;168:1205–1218. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.028035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borjigin J, Nathans J. Insertional mutagenesis as a probe of rhodopsin’s topography, stability, and activity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14715–14722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher TS, Taggart AKP, Zakian VA. Cell cycle-dependent regulation of yeast telomerase by Ku. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:1198–1205. doi: 10.1038/nsmb854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman KL, Cech TR. Essential functions of amino-terminal domains in the yeast telomerase catalytic subunit revealed by selection for viable mutants. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2863–2874. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.21.2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Sugino A. New yeast–Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six base-pair restriction sites. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschling DE, Aparicio OM, Billington BL, Zakian VA. Position effect at S. cerevisiae telomeres: reversible repression of Pol II transcription. Cell. 1990;63:751–762. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90141-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote E, Hao JC, Bennet MK, Kelly RB. A targeting signal in VAMP regulating transport to synaptic vesicles. Cell. 1995;81:581–589. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivessa AS, Zhou J-Q, Schulz VP, Monson EM, Zakian VA. Saccharomyces Rrm3p, a 5′ to 3′ DNA helicase that promotes replication fork progression through telomeric and subtelomeric DNA. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1383–1396. doi: 10.1101/gad.982902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivessa AS, Zhou J-Q, Zakian VA. The Saccharomyces Pif1p DNA helicase and the highly related Rrm3p have opposite effects on replication fork progression in ribosomal DNA. Cell. 2000;100:479–489. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80683-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad V, Szostak JW. A mutant with a defect in telomere elongation leads to senescence in yeast. Cell. 1989;57:633–643. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maina CV, Riggs PD, Grandea AG, III, et al. An Escherichia coli vector to express and purify foreign proteins by fusion to and separation from maltose-binding protein. Gene. 1988;74:365–373. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennock E, Buckley K, Lundblad V. Cdc13 delivers separate complexes to the telomere for end protection and replication. Cell. 2001;104:387–396. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaut G, Shevchenko A, Rutz B, et al. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:1030–1032. doi: 10.1038/13732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz VP, Zakian VA. The Saccharomyces PIF1 DNA helicase inhibits telomere elongation and de novo telomere formation. Cell. 1994;76:145–155. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski RS, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taggart AKP, Teng S-C, Zakian VA. Est1p as a cell cycle-regulated activator of telomere-bound telomerase. Science. 2002;297:1023–1026. doi: 10.1126/science.1074968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas BJ, Rothstein R. Elevated recombination rates in transcriptionally active DNA. Cell. 1989;56:619–630. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90584-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto Y, Taggart AKP, Zakian VA. The role of the Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2 complex in telomerase-mediated lengthening of Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomeres. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1328–1335. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00372-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega LR, Mateyak MK, Zakian VA. Getting to the end: telomerase access in yeast and humans. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:948–959. doi: 10.1038/nrm1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]