Abstract

Macrophages respond to infection with Legionella pneumophila by the induction of inflammatory mediators, including type I Interferons (IFN-Is). To explore whether the bacterial second messenger cyclic 3’-5’ diguanylate (c-diGMP) activates some of these mediators, macrophages were infected with L. pneumophila strains in which the levels of bacterial c-diGMP had been altered. Intriguingly, there was a positive correlation between c-diGMP levels and IFN-I expression. Subsequent studies with synthetic derivatives of cdiGMP, and newly described 3’-5’ diadenylate (c-diAMP), determined that these molecules activate overlapping inflammatory responses in human and murine macrophages. Moreover, UV cross-linking studies determined that both dinucleotides physically associate with a shared set of host proteins. Fractionation of macrophage extracts on a biotin-c-diGMP affinity matrix led to the identification of a set of candidate host binding proteins. These studies suggest that mammalian macrophages can sense and mount a specific inflammatory response to bacterial dinucleotides.

Keywords: L. pneumophila, cyclic dinucleotides, PAMPs, interferons (ifns), cytokines and signal transduction

1. Introduction

Legionella pneumophila, the cause of Legionnaires' Disease, owes its ability to replicate within macrophages to the Icm/Dot type IVb secretion apparatus. This virulence system injects specific “effector” proteins, subverting normally effective vesicular trafficking and enabling L. pneumophila to evade external host immunity (reviewed in [1, 2]). To defend against intracellular pathogens, the immune system has evolved overlapping innate sensors, known as pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which detect unique pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Upon recognizing their corresponding PAMPs, PRRs initiate a robust inflammatory response featuring the activation of inflammatory signaling cascades (e.g., NF-κB, IRFs, AP-1), which then induce the expression of cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α, Interferons [IFNs] and IL-6) and chemokines (reviewed in [3, 4]). PRRs include transmembrane spanning Toll like receptors (TLRs), cytosolic Nod like receptors (NLRs), membrane dependent RIG-I like receptors (RLRs) and a growing list of cytosolic nucleic acid sensors [5, 6].

Important PRRs in the innate response to L. pneumophila include, TLR2 (leading to TNF-α & IL-6 secretion), Naip5-NLRC4 (leading to inflammasome activation and IL-1β production) and an unknown receptor that directs the expression of type I IFNs (IFN-Is; [7–10]). Although recent studies have implicated L. pneumophila nucleic acids as IFN-I stimulating PAMPs, the mechanism by which requisite quantities of nucleic acids accumulate in the host is not apparent [11–15]. Intriguingly, recent studies have identified cyclic dinucleotides as another family of PAMPs that induce IFN-I expression [16–19].

Cyclic (3’-5’) diguanylate (c-diGMP) functions as an important second messenger to regulate bacterial programs, such as differentiation, transition from planktonic to biofilm growth, persistence and virulence [18, 20]. c-diGMP has also been found to functions as a potent adjuvant, stimulating the production of TNF-α, IL-1, IFN-β, IP-10 and RANTES/CCL5 [19]. Enzymes regulating the metabolism of this bacterial second messenger have been identified in most bacterial genomes; specifically, diguanylate cyclases featuring GGDEF (Gly-Gly-Asp-Glu-Phe) domains and c-diGMP phosphodiesterases with EAL (Glu-Ala-Leu) or HD-GYP (His-Asp, Gly-Tyr-Pro) domains [18, 20]. This includes the L. pneumophila, where 21 genes with GGDEF and/or EAL domains have been identified [21]. Ectopic over expression and deletion of these 21 cyclic diguanylate signaling (cdgS) genes have implicated them in several L. pneumophila functions [21]. More recently, studies have identified a second bacterial dinucleotide, cyclic (3’-5’) diadenylate (c-diAMP), which regulates bacterial DNA integrity (i.e., B. subtilis disA; [22]), as well as Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis [17]. Moreover, c-diAMP also induces IFN-I expression [17]. Moreover, diadenylate cyclases, featuring a DUF147 domain, and a corresponding phosphodiesterase have been found to be widely distributed amongst bacterial genomes [23].

Struck by the potent ability of virulent, but not avirulent, L. pneumophila to stimulate IFN-β expression, macrophages were infected with strains, in which c-diGMP levels had been perturbed, to explore a potential role for c-diGMP in bacterially induced IFN-I expression. Intriguingly, there was a strong positive correlation between c-diGMP levels and IFN-β response. Subsequent studies, with synthetic derivatives of c-diGMP, as well as c-diAMP, determined that these molecules stimulated remarkably similar inflammatory responses, in both murine and human macrophages. UV cross-linking and competition studies revealed that both cyclic dinucleotides physically associate with the same limited set of macrophage proteins. Fractionation of macrophage extracts on a c-diGMP affinity matrix led to the identification of candidate host dinucleotide binding proteins. These studies suggest that macrophages express a conserved innate response system that senses bacterial dinucleotides and then directs activation of a potent inflammatory response.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

HEK-293T, NIH-3T3 and Raw267.4 cells (ATCC, Manassas, Virginia, USA) were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen-GIBCO, Grand Island, NY), supplemented with 10% FCS (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and penicillin/streptomycin (P/S; Invitrogen-GIBCO). U937, HL-60, and J774 cells (ATCC) were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen-GIBCO), supplemented with 10% FCS and P/S. Bone marrow derived macrophages (BMMs) from C57Bl6/J, Stat1[−/−], IFNAR1[−/−], IRF3[−/−], TNFR1[−/−] and TBK1/TNFR1 double knockout mice were prepared and cultured in 20% L929 cell conditioned media, as previously reported [7, 24]. Some macrophages were immortalized with a v-myc/v-raf expressing retrovirus [25]. Cells were stimulated with IFN-αA/D (PBL, Piscataway, NJ), murine IFN-γ (PBL), PMA (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO), LPS (E. coli serotype 055:B5; Sigma-Aldrich), or by Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) mediated transfection with synthetic c-diAMP, c-diGMP or biotin-c-diGMP (> 99% pure; [26]).

2.2. Legionella pneumophila

L. pneumophila (JR32; restriction-defective Philadelphia-1, streptomycin-resistant) and mutant strains (JR32 background) were grown in AYE broth or on CYE plates [7]. Strains ectopically over expressing cdgS genes have recently been reported [21]. For infections, day 6, murine, bone marrow macrophages (BMMs; 2.0 × 106 per well of a 6-well plate) were infected with post-exponential phase L. pneumophila at MOI = 10 [7].

2.3. RT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared from day 6 BMMs, either before and after L. pneumophila infection or ligand stimulation by Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) lysis, transcribed into cDNA and amplified, as previously reported [7, 24], in a Stratagene MX3005p thermocycler (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with a SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and specific primers (see Table S1). Expression was normalized to a β-actin control and standard curves were generated by plotting log DNA concentration versus Ct values from 1:5 serial dilutions with MxPro software (Stratagene).

2.4. Biochemical Studies

Whole cell extracts (WCEs) were prepared from cells, as previously reported [7, 24], with the addition of 1× protease inhibitor (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Extracts were incubated with 1–2 µg of 2’-biotin-cyclic-diGMP (biotin-c-diGMP; [26]) for 20’ (in 50 mM Tris 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2; 4°C) prior to UV crosslinking (10,000 µW/cm2, 400 seconds, 4°C; Statalinker, Startagene). Reactants were fractionated by 12.5% PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose and visualized with Streptavidin-HRP (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and ECL (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NY). Competition studies entailed the simultaneous addition of increasing doses of c-diGMP or c-diAMP. Some cross-linked samples were also collected by streptavidin pull-down (Pierce), with standard “immunoprecipitation” conditions [24]. Cell fractionation studies entailed WCEs from eight T-flasks (150 cm2) of PMA (150 nM, 18 h; Sigma-Aldrich) treated U937 cells. WCEs were fractionated by 25%–60% [NH4]2SO4 precipitation, resuspended in 1.0 ml of 0.05% NP40, 40 mM Tris 7.4, 125 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 × protease inhibitor and dialyzed against 50 mM Tris 8.0, 125 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT. Post dialysis extract were applied to a 0.3 ml biotin-c-diGMP affinity matrix (200 µg of biotin-c-diGMP bound to Streptavidin-Agarose; Pierce) at 10 ml per hour. The column was washed with 10 column volumes and developed with a linear 6 ml 0.2–1.8 M NaCl gradient. 300 µl fractions were collected and snap frozen prior. Peak fractions were pooled, dialyzed and applied to a second c-diGMP column, which was washed with 5 buffer (5 col. vol.) and twice with 200 µl of GTP (150 µg). Bound proteins were batch eluted with two 150 µl volumes of c-diGMP (100 µg). Eluates were pooled, concentrated by TCA (10%) precipitation and fractionated by SDS PAGE (12% Precast Gels; BioRad, Richmond, CA). Silver stained (for Mass Spectrometry, Pierce) bands were excised and subjected to protein identification using liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) as previously reported [27].

3. Results

3.1. L. pneumophila induces IFN-β in a c-diGMP dependent manner

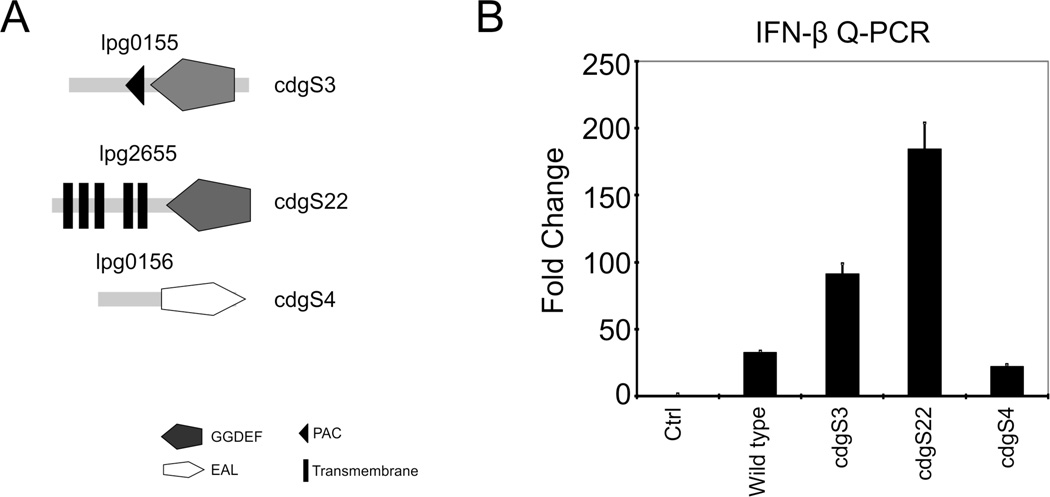

Previous studies have demonstrated that, like many other bacteria, L. pneumophila induces a robust expression of IFN-β, but in an Icm/Dot dependent manner [7–9]. Moreover, this IFN-β expression is dependent on the canonical TBK1-IRF3 axis [5–7]. Several recent of studies have implicated L. pneumophila derived nucleic acids (both RNA and DNA), either directly or indirectly, in the activation of the TBK1-IRF3-IFNβ axis; however, the mechanism by which sufficient quantities of these large molecules would escape from endosomes containing L. pneumophila into the cytosol to trigger an inflammatory response is not readily apparent [11–14]. To determine whether 3’,5’-cyclic diguanylate (c-diGMP), an important L. pneumophila second messenger, might contribute to this response, macrophages were infected with strains in which cdgS genes were ectopically expressed to alter bacterial c-diGMP levels [21]. Intriguingly, when murine BMM macrophages were infected with strains ectopically expressing cdgS3 (lpg0155) and cdgS22 (lpg2655), both associated with significantly elevated c-diGMP levels [21], IFN-β was more potently induced (see Fig. 1). In contrast, in macrophages infected with a strain ectopically expressing cdgS4 (lpg0156; an EAL only gene), associated with reduced c-diGMP levels, a reduction in IFN-β expression was observed (Fig. 1). These data raised the possibility that a small molecule, which may access the type IVb Icm/Dot secretion apparatus, is an important component of the acute IFN-β response to L. pneumophila infection.

Figure 1. L. pneumophila dependent IFN-β expression.

(A) Diagram of the L. pneumophila cdgS3, cdgS22 and cdgS4 genes. (B) IFN-β expression was evaluated by Q-PCR in d6 BMMs (C57Bl/6J) infected (MOI = 10; 6 h) with L. pneumophila (JR-32=Lp) strains stably transformed with IPTG inducible cdgS3, cdgS22 or cdgS4 expressing plasmids (see Panel A; [21]). Results were normalized to β-actin and reported as relative fold change [7].

3.2. Synthetic cyclic dinucleotides stimulate a potent inflammatory response

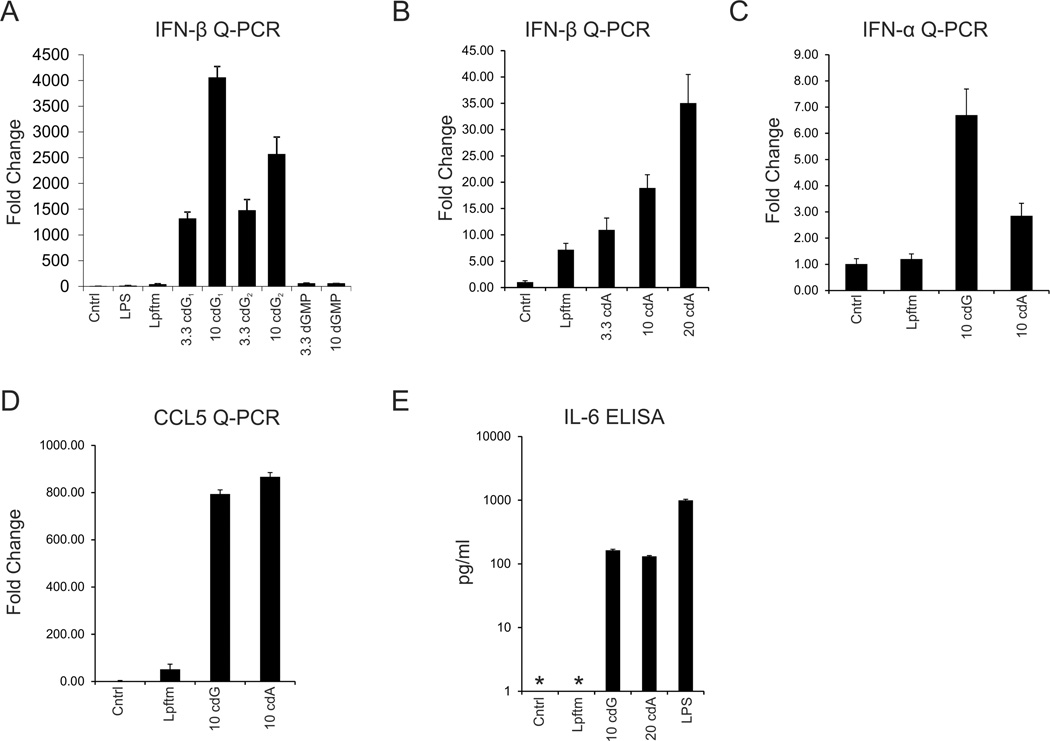

To more directly evaluate whether c-diGMP is an effective inducer of IFN-β expression synthetic c-diGMP was prepared [26] and transfected into murine macrophages. As previously reported [15, 16], there was a robust dose dependent induction of IFN-β expression. Moreover, synthetic c-diAMP, which has also recently been described as an inflammatory stimulant [17], was also found to effectively induce IFN-β expression, albeit less potently than c-diGMP (Fig. 2). Both dinucleotides also stimulated the expression of other inflammatory mediators, including IFN-α, RANTES/CCL5 and IL-6 (Fig. 2). Likewise, both dinucleotides stimulated the activation of an NF-κB reporter and Jnk (Fig. S1; data not shown), as previously reported [16].

Figure 2. Cyclic dinucleotides induce expression of IRF3 target genes.

(A, B) IFN-β expression was evaluated in d6 BMMs, by Q-PCR, 6 hours after lipofectamine (Lpftm) mediated transfection of (A) 2 preparations of synthetic c-diGMP (cdG; 3.3 or 10 µg), with dGMPas a negative control, or (B) synthetic c-diAMP (cdA; 3.3, 10 & 20 µg), as in Figure 1. (C, D) Cyclic dinucleotide dependent IFN-α (C) or CCL5 (D) expression in d6 BMMs was evaluated by Q-PCR, as above. (E) Cyclic dinucleotide dependent IL-6 secretion was evaluated after 6h by ELISA (Ebioscience) of d6 BMMs supernatants. Stimulation with LPS (1 µg/ml, 4h) served as a positive control. (* Not detected)

3.3. Synthetic cyclic dinucleotides signal through the canonical IRF3-IFN-β-IFN-α axis

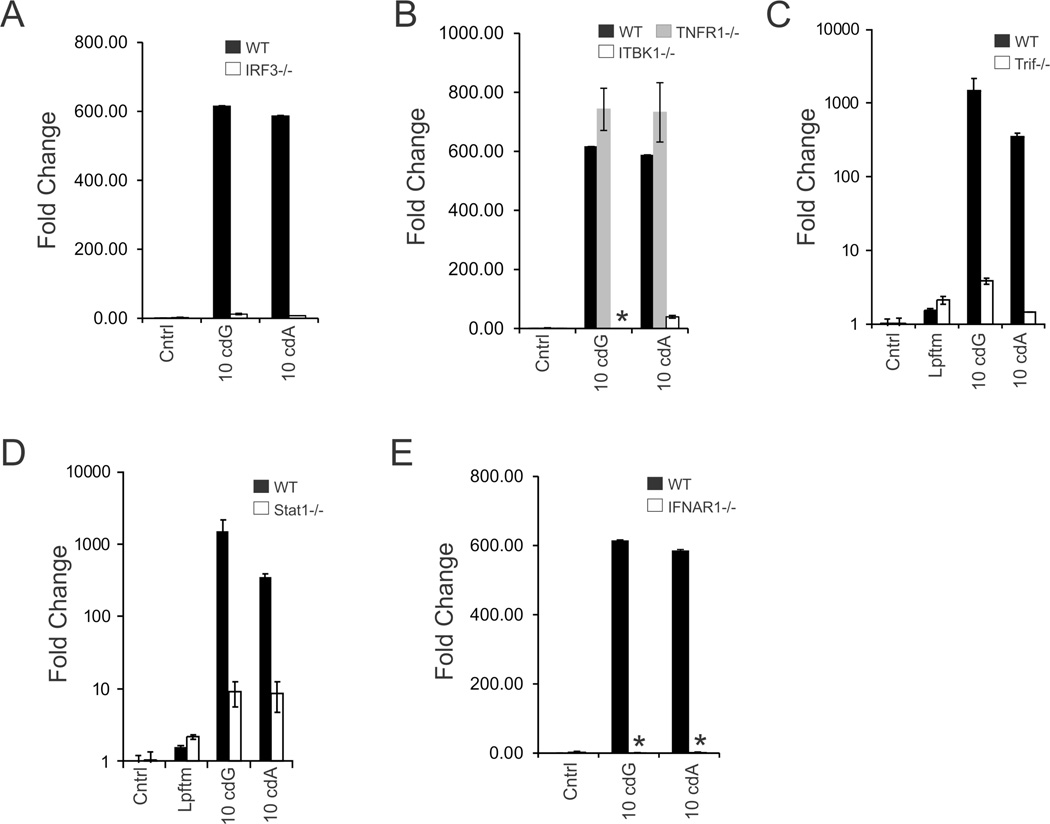

Previous studies on L. pneumophila determined that IFN-β induction was dependent on TBK1 and its target transcription factor, IRF3 [5–7, 12]. Consistent with a recent study exploring c-diGMP [16], cyclic dinucleotide dependent IFN-β induction was significantly reduced in IRF3 and TBK1 knockout macrophages (Fig. 3). However, in contrast to a prior study on MyD88/TRIF double knockouts [16], macrophages deficient in TRIF, an upstream regulator, also exhibited a substantial reduction in cyclic dinucleotide dependent IFN-β expression. The possibility that the IFN-I autocrine loop (i.e., including the IFN-α receptor and STAT signaling) amplifies the response to c-diGMP was evaluated next, since this loop is an important IFN-β target. Surprisingly, both IFN-α receptor chain 1 (IFNAR1) and Stat1 knockout macrophages exhibited significantly reduced responses to c-diGMP and c-diAMP (Fig. 3). These observations highlight an important role for the IFNAR-Stat1 axis in the innate response to cyclic dinucleotides.

Figure 3. Cyclic dinucleotides signal through the canonical IRF3-IFN-β-IFN-α axis.

(A–E) Cyclic dinucleotide dependent IFN-β expression was evaluated, as above in d6 BMMs form WT (C57Bl/6J) Stat1[−/−] and IFNAR1[−/−]) mice, or immortalized murine macrophages from WT (C57Bl/6J) IRF3[−/−], TNFR1[−/−] and TBK1/TNFR1 double knockout mice.

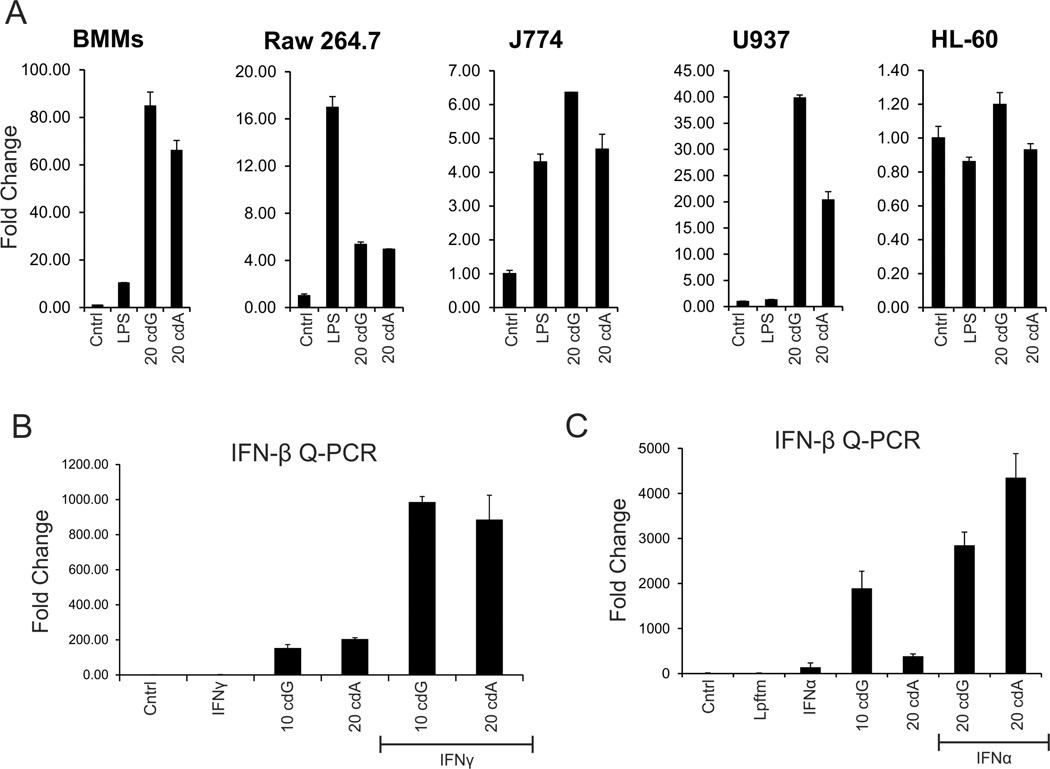

3.4. The inflammatory response to cyclic dinucleotides is conserved among macrophages

In preparation for a more rigorous biochemical analysis of the innate immune response to these cyclic dinucleotides, it was important to determine whether this response was conserved in established cell lines. This analysis included both human and murine macrophage lines (i.e., Raw264.7, J774, U937 and HL-60 cells). Consistent with recent studies for c-diGMP [16, 19], each of these macrophage lines, except HL60 cells, exhibited a robust IFN-β response to both cyclic dinucleotides (Fig. 4), whereas nonimmune cells, (i.e., NIH-3T3, MEFs, HEK-293T and HeLa cells; not shown; [16]) failed to exhibit a response. Of note, varying levels of basal IFN-β observed among these macrophages lines led to significant differences in reported fold induction. Again, there was a trend towards less potent responses to c-diAMP. Murine macrophages always yielded the most rigorous response.

Figure 4. The inflammatory response to cyclic dinucleotides is conserved in macrophages.

(A) Cyclic dinucleotide (cdG = c-diGMP; cdA = c-diAMP) dependent IFN-β expression was evaluated by Q-PCR in day 6 BMMs, Raw267.4, J774, U937 and HL-60 cells, as in Figure 1. Stimulation with LPS (1 µg/ml) served as a positive control. (B) Cyclic dinucleotide dependent IFN-β expression was evaluated in BMMs pretreated (18 h) with IFN-γ (50 U/ml; left panel) or IFN-α (1000 U/ml; right panel), as in panel A.

Since studies with IFNAR and Stat1 knockout macrophages had suggested that autocrine IFN-Is contributed to cyclic dinucleotide response, the ability of IFN-α or IFN-γ (also Stat1 dependent) pretreatment to enhance the inflammatory response was explored next. Consistent with the knockout studies (Fig. 3), both ligands significantly potentiated the inflammatory response to cyclic dinucleotides (Fig. 4). These observations suggest that one or more of the components mediating the innate response to cyclic dinucleotides is an IFN target gene.

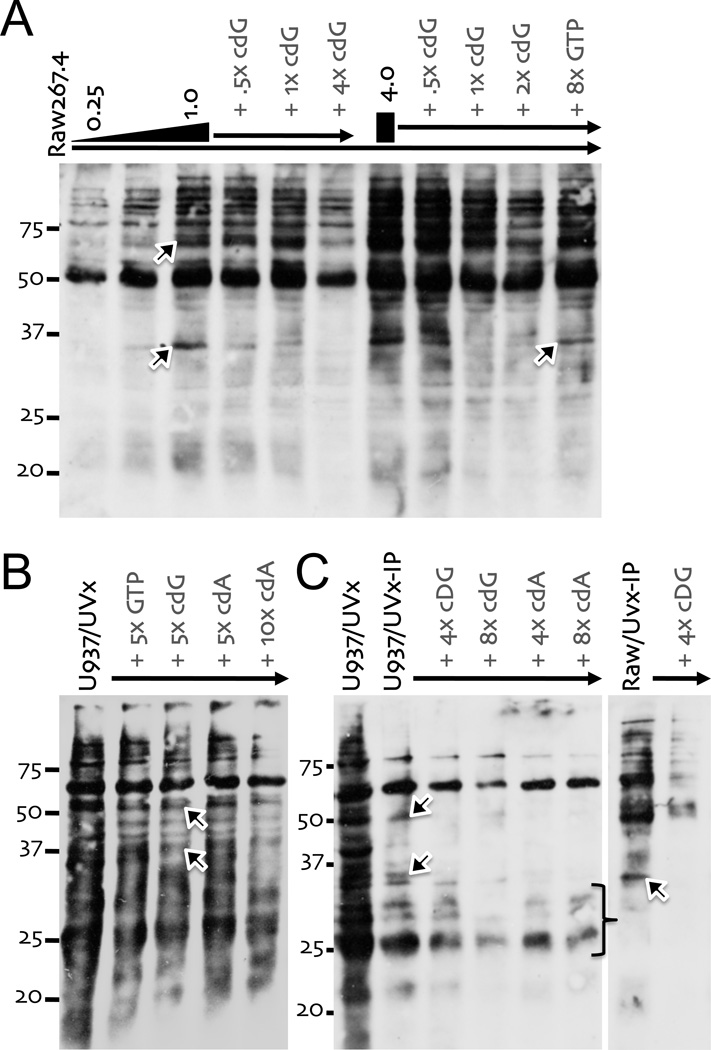

3.5. Biochemical characterization of host cyclic dinucleotide binding proteins

The development of a biotinylated derivative of c-diGMP provided an opportunity to carry out a biochemical analysis of the response to this ligand [26]. Initial studies determined that the biological response to biotin-c-diGMP was about 10 fold lower than native c-diGMP, suggesting this modification either impeded binding to the putative host receptor and/or subsequent downstream signaling events (Fig. S2A). Competition studies, taking advantage of this lower bioactivity, revealed that biotin-c-diGMP effectively competed with native c-diGMP for binding/activation of the host response system (data not shown; see also Fig. 5). Next, the photo-lability of guanidine was exploited to identify candidate binding proteins within macrophage extracts [28]. Specifically, biotin-c-diGMP was incubated with unstimulated Raw267.4 or PMA treated U937 cell extracts and then exposed to UV light. The reactants were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a membrane and probed with streptavidin-HRP to detect any proteins covalently modified with biotin (Fig. 5). The analysis revealed biotinylated proteins, even absent the biotin-c-diGMP probe, suggesting the presence of endogenously biotinylated proteins (data not shown; see also Fig. 5). More importantly, there was a biotin-c-diGMP, dose-dependent increase in unique biotin modified proteins in the Raw267.4 cell extracts (Fig. 5A). At least two of these bands of ~55–60 and 35 kDa were effectively competed by the addition of either excess c-diGMP or c-diAMP, but not GTP, prior to UV crosslinking (UVx), suggesting they represented specific host binding proteins (Fig. 5A). The pattern of crosslinked proteins was more complex in U937 cell extracts (Fig. 5B). Yet again, the addition of either excess c-diGMP or c-diAMP, but not GTP, prior to UVx led to a marked reduction in signal from specific bands of ~50–55 and 35 kDa. Furthermore, the complexity of crosslinked products in U937 cell extracts was substantially reduced if the crosslinked products were collected by streptavidin pulldown (i.e., UVx-IP) prior to gel fractionation (Fig. 5C). Similar results were obtained when Raw267.4 cell extracts were UVx-IPed (Fig. 5C). Moreover, UV crosslinking with 32P-c-diGMP (generated enzymatically from 32P-α-GTP) identified the same species, providing strong evidence that the biotin adduct did not affect stable association with host proteins (Fig. S2B; [28]). These studies identified a small subset of host proteins that appeared to specifically associate with both c-diGMP and c-diAMP.

Figure 5. Analysis of macrophage extracts with biotin-c-diGMP.

(A) Raw264.7 WCEs (1.5 µl) were incubated with biotin-c-diGMP (0.25, 0.5, 1 & 4 µg; 20 min, 4° C), treated UV light, fractionation on SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with Streptavidin-HRP. A molar excess of GTP, c-diGMP (cdG) or c-diAMP (cdA) competitors was added simultaneously with biotin-c-diGMP, as indicated. (B) PMA treated U937 cells WCEs were UV crosslinked (UVx) with biotin-c-diGMP (1 µg), with or without competitors, as in panel A. (C) Crosslinked samples, with or without competition, were collected from UV treated (UVx) U937 cell extracts (left panel) or Raw264.7 cell extracts (right panel) by streptavidin pulldown (UVx-IP), prior to gel fractionation.

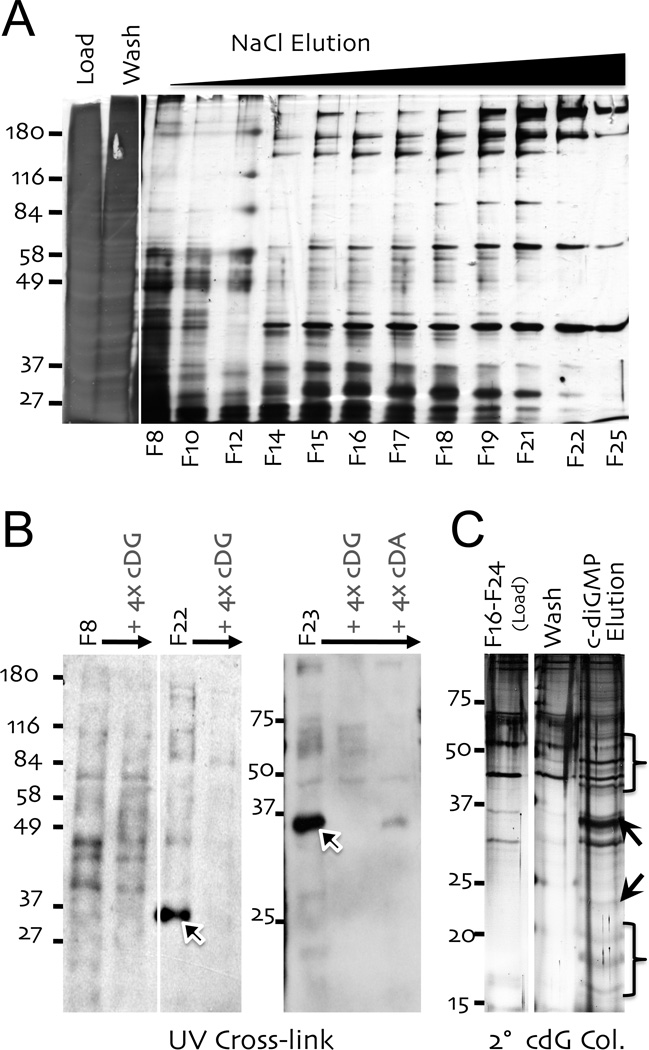

Next, PMA treated U937 whole cell extracts were fractionated on a biotin-c-diGMP affinity matrix with a linear (0.2–1.8 M) NaCl gradient. Remarkably, a substantially less complex mixture of proteins was recovered in these eluates (Fig. 6A). Analysis of several of the recovered fractions by UV cross-linking revealed a specific enrichment of the ~35 KDa binding protein, especially in the higher NaCl fractions (Fig. 6B). Again, this band was effectively competed by excess c-diGMP and c-diAMP. A more diffuse species, running at the 25 kDa marker, was partially enriched in the lower NaCl fractions (data not shown; see also Figs. 5C & S2A). Subsequently, pools of both low and high NaCl fractions were pooled and rechromatographed on a second biotin-c-diGMP column. However, this time bound proteins were eluted with c-diGMP, after a wash with GTP (to remove nonspecific binders). Silver stain revealed a number of specific bands, migrating at 15–20, ~22, ~35 and 40–55 kDa (Fig. 6C for high NaCl; low NaCl not shown). These bands were excised, digested and evaluated by mass spectrometry [27]. To simplify the number of the list of candidates identified, proteins not well expressed in leukocytes were excluded (Table S2). Likewise nuclear proteins were excluded since immunofluorescence studies localized c-diGMP binding proteins to the cytoplasm (Fig. S3). Of the ~30 most prominent binding proteins (Table S2), several were very prominent, including Coronin 1A in the 40–55 kDa band, mRNA cap guanine-N7 methyltransferase in the 35 kDa band and peptidyl-prolyl isomerase H (cyclophilin H) in the ≤ 20 kDa region. A notable feature among the many recovered proteins (Table S2) was either a known or putative GTP/ATP binding activity, suggesting the c-diGMP affinity matrix effectively enriched for nucleotide binding proteins.

Figure 6. Biotin-c-diGMP dependent affinity purification of binding proteins.

(A) [NH4]2SO4 precipitated U937 extracts were applied to a biotin–c-diGMP column, washed and eluted with a linear NaCl gradient (0.2–1.8 M; fractions 6–26). Fractions were evaluated by silver stained gel. (B) Fractions from panel A were evaluated by UV crosslinking, as in Figure 5. (C) Low NaCl (Fractions 10–14; not shown) and high NaCl Fractions (16–22) from column in panel A were pooled, dialyzed and re-chromatographed on second biotin–c-diGMP columns (2° cDG Col.). Both low and high NaCl pools columns were washed with buffer, followed by 300 µg of GTP, prior to elution with 200 µg of c-diGMP. Fractions from low (not shown) and high NaCl columns were evaluated by silver stained gel. Bands were excised, as indicated, for mass spectrometry analysis.

4. Discussion

Murine macrophages employ several PRR sensor and response pathways to direct an innate response to L. pneumophila. This includes TLR-MyD88 and Naip5-NLRC4 dependent pathways, as well as a distinct, less well-characterized IFN-I inducing pathway [2, 6, 10]. Curiously, IFN-Is, known for their potent antiviral activity, are also one of the most effective cytokines in suppressing L. pneumophila growth [7–9]. While there is compelling evidence that viral nucleic acids, detected by multiple PRRs, trigger IFN-I activation during a viral infection [5, 6], the role L. pneumophila nucleic acids play in stimulating this response is more controversial. Both published genetic and biochemical studies support a direct role for L. pneumophila nucleic acids in IFN-I activation [12–14]. Yet, neither the identity of the corresponding PRR nor the mechanism by which the requisite large quantities of bacterial nucleic acids accumulate within the appropriate cellular compartment has been elucidated. Several authors have suggested that bacterial nucleic acids “escape” into the cell through the L. pneumophila type IVb secretion system. It is, however, difficult to understand how these molecules overcome the size and specificity requirements of the Icm/Dot translocation system [1, 29].

Our own efforts to identify IFN-I activating PAMPs during a L. pneumophila infection have led us to examine c-diGMP, which may be small enough to access the Icm/Dot secretion system. These studies revealed that IFN-β expression correlated directly with bacterial c-diGMP levels in mutant L. pneumophila strains. Subsequent studies with synthetic c-diGMP highlighted its ability to potently stimulate IFN-β expression, as recently reported [16]. Comparison to another recently described IFN-I activating PAMP, c-diAMP [17], revealed that it activated an analogous inflammatory response, albeit somewhat less potently than c-diGMP. Intriguingly, however, IFN pretreatment both enhanced the inflammatory response to and reduced differences between c-diAMP and c-diGMP, suggesting that IFN stimulated genes contribute to this innate response.

Genetic studies exploring host components required for the inflammatory response to cyclic dinucleotides underscored the anticipated dependence on TBK1 and its IFN-β inducing substrate IRF-3 [7, 16]. Additional studies highlighted a dependence on TRIF, IFNAR1 and Stat1, suggesting that additional inputs contribute to the IFN-I response. Specifically, the IFNAR1 and Stat1 dependence indicated that autocrine IFN-Is amplify the innate response to cyclic dinucleotides. Evidence that IFN pretreatment enhanced the response to cyclic dinucleotides provided further support to this conclusion. Although the TRIF phenotype contradicted an earlier study [16], it raised the possibility that a TRIF-dependent TLR (i.e., TLR3 or TLR4) may enhance the innate response to cyclic dinucleotides. For example, RNA, previously implicated as a L. pneumophila PAMP, might potentiate the response to cyclic dinucleotides through TLR3 [13, 30, 31]. Alternatively, TRIF might independently regulate TRAF3, previously found to potentiate IFN-β induction [32]. Finally, differences in genetic backgrounds and purity of the stimulating cyclic dinucleotides may have contributed to the difference with the prior study [16]. Of note, in addition to their high purity (i.e., ≥ 99%; [26]) the inflammatory response to our cyclic dinucleotides was not affected by the absence of TLR4 (data not shown).

A biotinylated derivative of c-diGMP, albeit with reduced bioactivity, provided an opportunity to develop biochemical methods to probe for host binding proteins. Not only did competition studies provide evidence of host protein binding specificity, but they also revealed that c-diGMP and c-diAMP competed for the same host proteins. Consistent with functional studies (Figs. 2–4), c-diAMP was a less effective competitor than c-diGMP (Fig. 5). Specifically, biochemical studies identified a handful of specific host binding partners in the 45–55 kDa range (varied between murine and human extracts), as well as in the 35 kDa and 25 kDa region of the gel. In addition, a number of smaller species (i.e., ≥20 kDa) were eluted in a c-diGMP dependent manner from the secondary biotin-c-diGMP column. Mass spectrometry analysis of these bands identified a number of candidate binding proteins, many of which featured nucleotide binding domains (Table S2). Coronin 1A was the most prominent species identified in the 40–55 kDa region, whereas the mRNA cap guanine-N7 methyltransferase was by far the most prominent protein recovered in the 35 kDa band. Likewise, peptidyl-prolyl isomerase H (cyclophilin H) was most prominent in the ≤ 20 kDa region. Future studies will employ both knockdown and knockout approaches to rigorously explore the potential role these candidate binding proteins play in the innate response to cyclic dinucleotides.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by the NIH grants, AI096088 (CS) & AI058211 (CS) and AI23549 (HS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Franco IS, Shuman HA, Charpentier X. The perplexing functions and surprising origins of Legionella pneumophila type IV secretion effectors. Cell. Microbiol. 2009;11:1435–1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ninio S, Roy CR. Effector proteins translocated by Legionella pneumophila: strength in numbers. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:372–380. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trinchieri G, Sher A. Cooperation of Toll-like receptor signals in innate immune defence. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:179–190. doi: 10.1038/nri2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Regulation of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Science. 2010;327:291–295. doi: 10.1126/science.1183021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barber GN. Innate immune DNA sensing pathways: STING, AIMII and the regulation of interferon production and inflammatory responses. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2011;23:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trinchieri G. Type I interferon: friend or foe? J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:2053–2063. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plumlee CR, Lee C, Beg AA, Decker T, Shuman HA, Schindler C. Interferons direct an effective innate response to Legionella pneumophila infection. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:30058–30066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiavoni G, Mauri C, Carlei D, Belardelli F, Pastoris MC, Proietti E. Type I IFN protects permissive macrophages from Legionella pneumophila infection through an IFN-gamma-independent pathway. J. Immunol. 2004;173:1266–1275. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coers J, Vance RE, Fontana MF, Dietrich WF. Restriction of Legionella pneumophila growth in macrophages requires the concerted action of cytokine and Naip5/Ipaf signalling pathways. Cell. Microbiol. 2007;9:2344–2357. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vance RE, Isberg RR, Portnoy DA. Patterns of pathogenesis: discrimination of pathogenic and nonpathogenic microbes by the innate immune system. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanneganti TD, Ozoren N, Body-Malapel M, Amer A, Park JH, Franchi L, Whitfield J, Barchet W, Colonna M, Vandenabeele P, Bertin J, Coyle A, Grant EP, Akira S, Nunez G. Bacterial RNA and small antiviral compounds activate caspase-1 through cryopyrin/Nalp3. Nature. 2006;440:233–236. doi: 10.1038/nature04517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stetson DB, Medzhitov R. Recognition of cytosolic DNA activates an IRF3-dependent innate immune response. Immunity. 2006;24:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monroe KM, McWhirter SM, Vance RE. Identification of host cytosolic sensors and bacterial factors regulating the type I interferon response to Legionella pneumophila. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000665. e1000665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiu YH, Macmillan JB, Chen ZJ. RNA polymerase III detects cytosolic DNA and induces type I interferons through the RIG-I pathway. Cell. 2009;138:576–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sauer JD, Sotelo-Troha K, von Moltke J, Monroe KM, Rae CS, Brubaker SW, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Woodward JJ, Portnoy DA, Vance RE. The N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced Goldenticket mouse mutant reveals an essential function of Sting in the in vivo interferon response to Listeria monocytogenes and cyclic dinucleotides. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:688–694. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00999-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McWhirter SM, Barbalat R, Monroe KM, Fontana MF, Hyodo M, Joncker NT, Ishii KJ, Akira S, Colonna M, Chen ZJ, Fitzgerald KA, Hayakawa Y, Vance RE. A host type I interferon response is induced by cytosolic sensing of the bacterial second messenger cyclic-di-GMP. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:1899–1911. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woodward JJ, Iavarone AT, Portnoy DA. c-di-AMP secreted by intracellular Listeria monocytogenes activates a host type I interferon response. Science. 2010;328:1703–1705. doi: 10.1126/science.1189801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hengge R. Principles of c-di-GMP signalling in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:263–273. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karaolis DK, Means TK, Yang D, Takahashi M, Yoshimura T, Muraille E, Philpott D, Schroeder JT, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Talbot BG, Brouillette E, Malouin F. Bacterial c-di-GMP is an immunostimulatory molecule. J. Immunol. 2007;178:2171–2181. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan H, Chen W. 3',5'-Cyclic diguanylic acid: a small nucleotide that makes big impacts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:2914–2924. doi: 10.1039/b914942m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levi A, Folcher M, Jenal U, Shuman HA. Cyclic diguanylate signaling proteins control intracellular growth of Legionella pneumophila. mBio. 2011;2 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00316-10. e00316-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witte G, Hartung S, Buttner K, Hopfner KP. Structural biochemistry of a bacterial checkpoint protein reveals diadenylate cyclase activity regulated by DNA recombination intermediates. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finn RD, Mistry J, Tate J, Coggill P, Heger A, Pollington JE, Gavin OL, Gunasekaran P, Ceric G, Forslund K, Holm L, Sonnhammer EL, Eddy SR, Bateman A. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D211–D222. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao W, Cha EN, Lee C, Park CY, Schindler C. Stat2-Dependent Regulation of MHC Class II Expression. J. Immunol. 2007;179:463–471. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blasi E, Mathieson BJ, Varesio L, Cleveland JL, Borchert PA, Rapp UR. Selective immortalization of murine macrophages from fresh bone marrow by a raf/myc recombinant murine retrovirus. Nature. 1985;318:667–670. doi: 10.1038/318667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grajkowski A, Cieslak J, Gapeev A, Schindler C, Beaucage SL. Convenient synthesis of a propargylated cyclic (3'–5') diguanylic Acid and its "click" conjugation to a biotinylated azide. Bioconjug. Chem. 2010;21:2147–2152. doi: 10.1021/bc1003857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singla N, Erdjument-Bromage H, Himanen JP, Muir TW, Nikolov DB. A semisynthetic Eph receptor tyrosine kinase provides insight into ligand- induced kinase activation. Chem. Biol. 2011;18:361–371. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumagai Y, Matsuo J, Hayakawa Y, Rikihisa Y. Cyclic di-GMP signaling regulates invasion by Ehrlichia chaffeensis of human monocytes. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:4122–4133. doi: 10.1128/JB.00132-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cambronne ED, Roy CR. Recognition and delivery of effector proteins into eukaryotic cells by bacterial secretion systems. Traffic. 2006;7:929–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanneganti TD, Body-Malapel M, Amer A, Park JH, Whitfield J, Taraporewala ZF, Miller D, Patton JT, Inohara N, Nunez G. Critical role for cryopyrin/Nalp3 in activation of caspase-1 in response to viral infection and double-stranded RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:36560–36568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607594200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sander LE, Davis MJ, Boekschoten MV, Amsen D, Dascher CC, Ryffel B, Swanson JA, Muller M, Blander JM. Detection of prokaryotic mRNA signifies microbial viability and promotes immunity. Nature. 2011;474:385–389. doi: 10.1038/nature10072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hacker H, Tseng PH, Karin M. Expanding TRAF function: TRAF3 as a tri-faced immune regulator. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:457–468. doi: 10.1038/nri2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.