Abstract

Background

The incidence and predictors of heart failure (HF) post myocardial infarction (MI) with modern post-MI treatment have not been well characterized.

Methods and Results

2201 stable patients with persistent infarct related artery occlusion > 24 hours after MI with left ventricular ejection fraction <50% and/or proximal coronary artery occlusion were randomized to percutaneous intervention plus optimal medical therapy (PCI) or optimal medical therapy (MED) alone. Centrally adjudicated HF hospitalizations for NYHA III/IV HF and mortality were determined in patients with and without baseline HF, defined as a history of HF, Killip Class > I at index MI, rales, S3 gallop, NYHA II at randomization, or NYHA > I prior to index MI. Long-term follow-up data were used to determine 7-year life-table estimated event rates and hazard ratios.

There were 150 adjudicated HF hospitalizations during a mean follow-up of 6 years with no difference between the randomized groups (7.4% PCI vs. 7.5% MED, p=0.97). Adjudicated HF hospitalization was associated with subsequent death (44.0% vs. 13.1%, HR 3.31, 99% CI 2.21–4.92, p<0.001). Baseline HF (present in 32% of patients) increased the risk of adjudicated HF hospitalization (13.6% vs. 4.7%, HR 3.43, 99% CI 2.23–5.26, p<0.001) and death (24.7% vs. 10.8%, HR 2.31, 99% CI 1.71–3.10, p<0.001).

Conclusions

In the overall OAT population, adjudicated HF hospitalizations occurred in 7.5% of subjects and were associated with increased risk of subsequent death. Baseline or prior HF was common in the OAT population and was associated with increased risk of hospitalization and death.

Keywords: Heart Failure, Myocardial Infarction, Occlusion, Revascularization

Background

Heart failure (HF) occurring during or after myocardial infarction (MI) is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.1, 2 Previous studies on the incidence and predictors of HF post-MI are based on observational population-based studies, have limited information on clinical characteristics and medication use, are characterized by incomplete definitions of outcome events and have reported conflicting results.3–7 The Framingham Heart Study reported a decrease in mortality but an increase in HF following MI from 1970 to 1999.4 Data from the Worcester Heart Attack Study adjusted for age, gender, diabetes, angina history, prior heart failure, hypertension, prior stroke and type of MI suggested an increased risk of heart failure post-MI from 1981 to 2001.7 In contrast, data from Olmsted County, Minnesota demonstrated a decrease in the risk of developing HF post-MI in 1994 versus in 1979.5, 6 Estimates of the risk of HF derived from post-MI clinical trials are not generalizable to the majority of patients in clinical practice settings due to the exclusion of patients with relatively preserved ejection fraction. 7–12

Persistent total occlusion of the infarct-related artery post MI was identified as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular mortality and morbidity after MI (odds ratio 1.73, 95% CI 1.22–2.47) in a subanalysis of the SAVE study.13 The Occluded Artery Trial (OAT) enrolled stable patients with persistent total occlusion of an infarct-related artery post infarct and left ventricular ejection fraction <50% and/or proximal coronary artery occlusion)14 with long-term follow up data. The independent blinded central adjudication of heart failure hospitalization and mortality events in OAT provides an opportunity to characterize the incidence and predictors of post-MI morbidity and mortality in this clinical trial population with a broad range of post- MI left ventricular function more representative of that encountered in clinical practice.

Methods

Patient Population

The design and primary results of OAT have been described previously.14, 15 Briefly, OAT enrolled 2201 patients with persistent infarct-related artery (IRA) occlusion > 24 hours (3 to 28 calendar days, with symptom onset on day 1) after MI and with left ventricular ejection fraction < 50% or proximal coronary artery occlusion. Key exclusion criteria included NYHA III or IV HF, shock, rest angina or severe ischemia on stress test, serum creatinine concentration higher than 2.5 mg per deciliter, left main or three-vessel coronary artery disease, or rest angina.14 Patients were randomly assigned to percutaneous coronary intervention plus optimal medical therapy (PCI) or optimal medical therapy (MED) alone. All patients were to receive aspirin, beta-blockade, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition or angiotensin receptor blockade, lipid-lowering therapy, and anti-coagulation as clinically indicated. Thienopyridine therapy was started prior to PCI and continued for at least 2–4 weeks in patients who underwent placement of a coronary stent.14 During the early phase of trial enrollment thienopyridine therapy was to be initiated before PCI and continued for 2 to 4 weeks in patients who underwent stenting. Following reports of enhanced efficacy of prolonged treatment with these agents after PCI, this therapy was recommended in both study groups for 1 year after MI.16, 17 Institutional review boards at the participating centers approved the study protocol. All patients provided written informed consent.

Heart Failure and Mortality Assessment

The primary endpoint of OAT was a composite of death from any cause, reinfarction and hospitalization for HF. To avoid ascertainment bias, all hospitalizations for cardiovascular events and pneumonia were submitted by sites for review by a central adjudication committee. The process for central adjudication of HF events has been previously described.15 Briefly, the adjudication committee reviewed all site-reported cardiovascular and pneumonia hospitalizations for each patient until an NYHA class III or IV event was adjudicated. After an NYHA class III or IV event was adjudicated, no further HF events for that patient were reviewed. In addition to review of site-reported events, there was active surveillance for HF admissions during all follow up contacts with OAT patients. For this report, centrally adjudicated, first reported hospitalizations for NYHA Class III and IV HF are reported as “adjudicated HF hospitalizations” and site-reported HF hospitalizations are reported as “site-reported HF hospitalizations.” Mortality events were also centrally reviewed to confirm the reported mortality event. This report presents long-term follow-up HF hospitalization and mortality data. Long-term follow-up data pertaining to other OAT outcomes have been published.1 Maximum follow-up was nine years and mean follow-up was six years.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics and medication use at discharge from hospitalization for index MI were compared between those patients who experienced an adjudicated HF hospitalization during follow-up and those who did not. Continuous variables were compared by Student t-test and categorical variables were compared by a Fisher exact or a chi-square test. Estimates of the cumulative adjudicated HF hospitalization event rate were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method and groups were compared with the use of log-rank tests of the 7-year curves. The Kaplan-Meier and multivariate analysis performed reflects centrally adjudicated, first reported HF hospitalizations for NYHA III/IV HF.

Comparisons were performed between assigned treatment groups with and without baseline HF. 7-year life-table estimated event rates were used to determine the effect of baseline HF on the risk of death, the effect of adjudicated HF hospitalization during follow-up on the risk of subsequent death (time-dependent analysis), and the effect of low EF (<40%) on adjudicated HF hospitalization risk. Although the maximum follow-up period was 9 years, 7-year life-table event rates were used because estimates beyond 7 years were considered less stable. A multivariate Cox-proportional hazards model was developed to determine the predictors of adjudicated HF hospitalization in all OAT patients, and in those with baseline vs. those without baseline HF (defined as a history of HF, Killip Class > I at index MI, rales, S3 gallop, NYHA II at randomization, or history of NYHA > I HF prior to index MI). Backward elimination was used with p≤0.01 for variables remaining in the final model. The OAT protocol pre-specified a significance level ≤0.01 for secondary end points. Results are reported with 99% confidence intervals.

Results

Characteristics at Study Entry

Clinical characteristics at study entry of patients with and without adjudicated HF hospitalization during follow up are shown in Table 1. Patients with an adjudicated HF hospitalization during follow-up were older (64.0 ±11.0 vs. 58.2 ±10.9 years, p<0.0001) with a greater proportion of women (33.3 vs. 21.2%, p=0.005) and black patients (7.3 vs. 2.8%, p=0.01). They had a greater frequency of co-morbid conditions including peripheral arterial disease (10.7 vs. 3.3%, p <0.0001), diabetes mellitus (42.0 vs. 19.1%, p<0.001), and hypertension (64.7 vs. 47.5%, p<0.001) when compared with those with no adjudicated HF hospitalization during follow-up. Patients with an adjudicated HF hospitalization during follow-up more often had the left anterior descending artery as the infarct-related artery (46.0 vs. 35.3%, p=0.008), had lower left ventricular ejection fraction (39.8 ±11.5 vs. 48.3 ±10.9%, p<0.0001), and tended to more often have multi-vessel coronary artery disease (23.3 vs. 16.9%, p=0.045). Collateral vessels were less likely to be visualized at index angiography among those who subsequently experienced an adjudicated HF hospitalization (81.1 vs. 89.0% without HF hospitalization, p=0.004).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with and without adjudicated HF hospitalization in follow-up

| No adjudicated HF hospitalization |

Adjudicated HF hospitalization |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=2051 | N=150 | ||||

| Demographics | P | ||||

| Mean age at randomization (years) | 58.2±10.9 | 64.0±11.0 | <0.0001 | ||

| No./Total | % | No./Total | % | p | |

| Age > 65 | 568/2051 | 27.7 | 73/150 | 48.7 | <0.0001 |

| Female | 434/2051 | 21.2 | 50/150 | 33.3 | 0.005 |

| White | 1643/2051 | 80.1 | 120/150 | 80.0 | 0.01 |

| Black | 58/2051 | 2.8 | 11/150 | 7.3 | |

| Hispanic | 261/2051 | 12.7 | 16/150 | 10.7 | |

| Other | 89/2051 | 4.3 | 3/150 | 2.0 | |

| Randomized to PCI | 1025/2051 | 50.0 | 76/150 | 50.7 | |

| Randomized to Medical Therapy | 1026/2051 | 50.0 | 74/150 | 49.3 | 0.87 |

| Clinical History | No. | % | No. | % | P |

| Angina | 456/2051 | 22.2 | 39/150 | 26.0 | 0.29 |

| Prior Myocardial Infarction | 223/2051 | 10.9 | 24/150 | 16.0 | 0.0548 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 72/2051 | 3.5 | 10/150 | 6.7 | 0.0488 |

| Stroke | 56/2051 | 2.7 | 7/150 | 4.7 | 0.17 |

| Peripheral-vessel Disease | 67/2049 | 3.3 | 16/150 | 10.7 | <0.0001 |

| Renal insufficiency | 26/2051 | 1.3 | 4/150 | 2.7 | 0.15 |

| Prior PCI | 93/2051 | 4.5 | 12/150 | 8.0 | 0.0546 |

| Prior CABG | 8/2051 | 0.4 | 1/150 | 0.7 | 0.47 |

| Prior HF | 38/2049 | 1.9 | 14/150 | 9.3 | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes Mellitus (DM) | 391/2051 | 19.1 | 63/150 | 42.0 | <0.0001 |

| DM with Insulin | 101/2051 | 4.9 | 23/150 | 15.3 | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 974/2051 | 47.5 | 97/150 | 64.7 | <0.0001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 1066/2050 | 52.0 | 76/150 | 50.7 | 0.75 |

| Current Cigarette Use | 816/2051 | 39.8 | 43/150 | 28.7 | 0.007 |

|

Characteristics (at randomization) |

P | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.5±5.0 | 28.8 ± 6.3 | 0.41 | ||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 71.4 ± 11.9 | 76.2 ± 12.5 | <0.0001 | ||

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 120.9± 17.8 | 120.0 ± 20.7 | 0.56 | ||

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 72.4 ± 112 | 71.6 ± 12.6 | 0.42 | ||

| No./Total | % | No./Total | % | P | |

| Presence of S3 | 33/2050 | 1.6 | 5/150 | 3.3 | 0.12 |

| Rales | 113/2047 | 5.5 | 24/150 | 16.0 | <0.0001 |

| Killip Class II–IV during index MI | 361/2042 | 17.7 | 56/150 | 37.3 | <0.0001 |

| Lab Data | P | ||||

| GFR (ml/min/1.73m2) by MDRD | 81.0 ± 21.1 | 75.1 ± 25.2 | 0.001 | ||

| Blood glucose (mg/dL)* | 118.7 ± 40.9 | 135.9 ± 52.2 | <0.0001 | ||

| No./Total | % | No./Total | % | p | |

| CKD with GFR< 60 | 278/2011 | 13.8 | 42/149 | 28.2 | <0.0001 |

| Total CK ≥ 2 times ULN | 1433/1743 | 82.2 | 104/128 | 81.3 | 0.78 |

| CK-MB ≥ ULN | 1280/1455 | 88.0 | 88/100 | 88.0 | 0.99 |

| Troponin I ≥ 2 times ULN | 1165/1263 | 92.2 | 93/96 | 96.9 | 0.10 |

| Troponin T > 2 times ULN | 319/438 | 72.8 | 23/31 | 74.2 | 0.87 |

| Other Data | P | ||||

| Interval between MI and randomization (days) |

11.1+7.7 | 10.3±7.7 | 0.27 | ||

| Ejection Fraction Mean (%) | 48.3±10.9 | 39.8±11.5 | <0.0001 | ||

| No. | % | No. | % | P | |

| EF>50% | 980/2035 | 48.2 | 35/150 | 23.3 | <0.0001 |

| EF<40% | 375/2035 | 18.4 | 74/150 | 49.3 | <0.001 |

| NYHA class I prior to index MI | 1652/2050 | 80.6 | 89/150 | 59.3 | <0.0001 |

| NYHA class II prior to index MI | 358/2050 | 17.5 | 57/150 | 38.0 | |

| NYHA class III–IV prior to index MI | 40/2050 | 2.0 | 4/150 | 2.7 | |

| NYHA class II at randomization | 313/2047 | 15.3 | 54/150 | 36.0 > | <0.0001 |

| ST elevation or new Q waves or R wave loss |

1777/2051 | 86.6 | 130/150 | 86.7 | 0.99 |

| Thrombolytic therapy during first 24 hours after onset of index MI |

392/2050 | 19.1 | 32/150 | 21.3 | 0.51 |

| Angiographic Data | No./Total | % | No./Total | % | P |

| Infarct Related Artery (IRA) | |||||

| LAD | 724/2051 | 35.3 | 69/150 | 46.0 | 0.0017 |

| LCX | 306/2051 | 14.9 | 29/150 | 19.3 | |

| RCA | 1021/2051 | 49.8 | 52/150 | 34.7 | |

| Multivessel Disease | 344/2033 | 16.9 | 35/150 | 23.3 | 0.0454 |

| No Collateral Vessels present | 223/2025 | 11.0 | 28/148 | 18.9 | 0.0037 |

| No Baseline HF Features (history of HF, Killip Class > I at index MI, rales, S3 gallop, NYHA > I prior to index MI, or NYHA II at randomization)+ |

1443/2051 | 70.4 | 61/150 | 40.7 | |

| At least one baseline HF feature | 608/2051 | 29.6 | 89/150 | 59.3 | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: BMI – Body Mass Index, BP – Blood Pressure, CABG – Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting, CK – Creatine Kinase, CKD – Chronic Kidney Disease, DM – Diabetes Mellitus, GFR – Glomerular Filtration Rate, LAD – Left Anterior Descending, LCX – Left Circumflex, MDRD - Modification of Diet in Renal Disease, PCI – Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, RCA – Right Coronary Artery, ULN – Upper Limit of Normal

represents fasting and random

Among 2201 patients in the study, 327 (14.9%) patients had 1 of these features, 224 (10.2%) had 2, 104 (4.7%) had 3, 28 (1.3%) had 4, 13 (0.6%) had 5, and 1 patient had all 6 features.

There was a small numerical difference that did not meet the pre-specified statistical criteria for significance in beta-blocker use at discharge between those who experienced an adjudicated HF hospitalization and those who did not (82% and 88% respectively, p=0.03). A greater proportion of patients with an adjudicated HF hospitalization received heart failure medications at index hospital discharge, including ACE inhibitors or ARBs, diuretics, spironolactone and digoxin when compared with patients with no adjudicated HF hospitalization (Table 2). Of the 1823 patients not on diuretics at discharge, 345 (19.2%) were placed on diuretics for at least one follow up visit in the first 60 months post discharge.

Table 2.

Medications at discharge for patients with and without an adjudicated HF hospitalization

| No centrally confirmed HF hospitalization N=2051 |

Centrally confirmed HF hospitalization N=150 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication Use on Discharge | No. | % | No. | % | P |

| Long acting nitrate | 459 | 22.4 | 39 | 26.0 | 0.31 |

| Beta-Blocker | 1809 | 88.2 | 123 | 82.0 | 0.03 |

| Calcium-Channel Blocker | 117 | 5.7 | 12 | 8.0 | 0.25 |

| Aspirin | 1966 | 95.9 | 139 | 92.7 | 0.06 |

| Thienopyridine(clopidogrel or ticlodipine) |

1237 | 60.3 | 92 | 61.3 | 0.80 |

| Warfarin | 193 | 9.4 | 22 | 14.7 | 0.04 |

| Insulin | 112 | 5.5 | 25 | 16.7 | <0.0001 |

| ACE inhibitor | 1586 | 77.3 | 128 | 85.3 | 0.02 |

| ACE-inhibitor or ARB | 1637 | 79.8 | 134 | 89.3 | 0.004 |

| Diuretic | 305 | 14.9 | 66 | 44.0 | <0.0001 |

| Digoxin | 41 | 2.0 | 20 | 13.3 | <0.0001 |

| Lipid lowering | 1667 | 81.3 | 121 | 80.7 | 0.85 |

| Spironolactone | 105 | 5.1 | 19 | 12.7 | 0.0001 |

| Antiarrhythmic (other than BB) | 69 | 3.4 | 15 | 10.0 | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: ACE – Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme, ARB – Angiotensin Receptor Blocker, BB – Beta-Blocker

Adjudicated, first episode HF hospitalization and subsequent site-reported HF hospitalization

Over 6-years mean follow-up, there were 150 patients with an adjudicated hospitalization. Of 161 patients with site-reported, any class HF hospitalizations, 140 (87%) were confirmed as reaching the primary endpoint by the adjudication committee. Ten additional patients, reported by sites but thought by sites not to have had class III or IV HF were determined to have experienced class III or IV HF hospitalization based on central review and included in the adjudicated HF hospitalization group. Adjudicated HF and site reported class III or IV HF events were in close agreement (Kappa = 0.89 95%CI (0.86 – 0.93))."

Of the 150 patients with an adjudicated NYHA hospitalization, 62 had at least one additional site-reported HF hospitalization (total 110 additional site-reported hospitalizations). The average number of site-reported repeat HF hospitalizations during follow-up per patient was 1.77 (based on N=62). Among the 62 patients with site-reported repeat HF hospitalizations who survived until the end of the study follow up period, the average number of site-reported repeat HF hospitalizations per patient was 1.65. Among the 62 patients with site-reported repeat HF hospitalization who died before the end of the study, the average number of site-reported repeat HF hospitalizations was 1.93.

Adjudicated HF hospitalization and all cause mortality risk by treatment assignment

Adjudicated HF hospitalizations did not differ according to randomized treatment assignment (7-year estimated life-table rates: 7.4% PCI vs. 7.5% MED, HR 1.01, 99% CI 0.66–1.54, p=0.97). There were 303 deaths over the follow-up period. Deaths did not differ according to randomized treatment assignment (7- year estimated life-table rate 14.6% PCI vs. 16.0% MED, HR=0.98, 99% CI 0.73–1.31, p=0.85).1 The combined outcome of adjudicated HF hospitalization or death did not differ according to treatment assignment (7-year estimated life-table rates: 18.7% PCI vs. 20.6% MED, HR 0.97, 99% CI (0.74–1.26), p=0.76). In both treatment groups, adjudicated HF hospitalization was significantly associated with excess risk of subsequent death (HR 6.32, 99% CI 3.70–10.79, p<0.001 for PCI patients and HR 5.96, 99% CI 3.45–10.31, p<0.001 for MED patients). In multivariate analysis, adjusted for history of cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, prior PCI, age, ejection fraction, chronic kidney disease, and history of baseline heart failure, adjudicated HF hospitalization among all patients was associated with increased risk of death (HR 3.31, 99% CI (2.21–4.92), p<0.001) with no difference between PCI patients (HR 3.34, 99% CI (1.86- 5.97), p<0.001 and MED patients (HR 3.27, 99% CI (1.85–5.80), p<0.001).

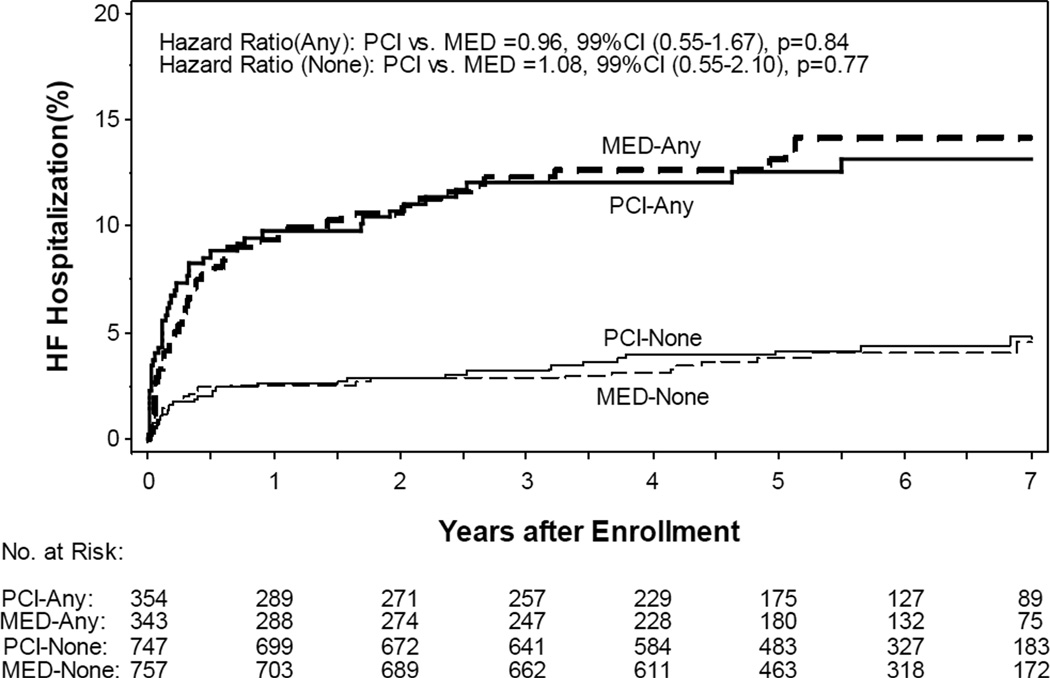

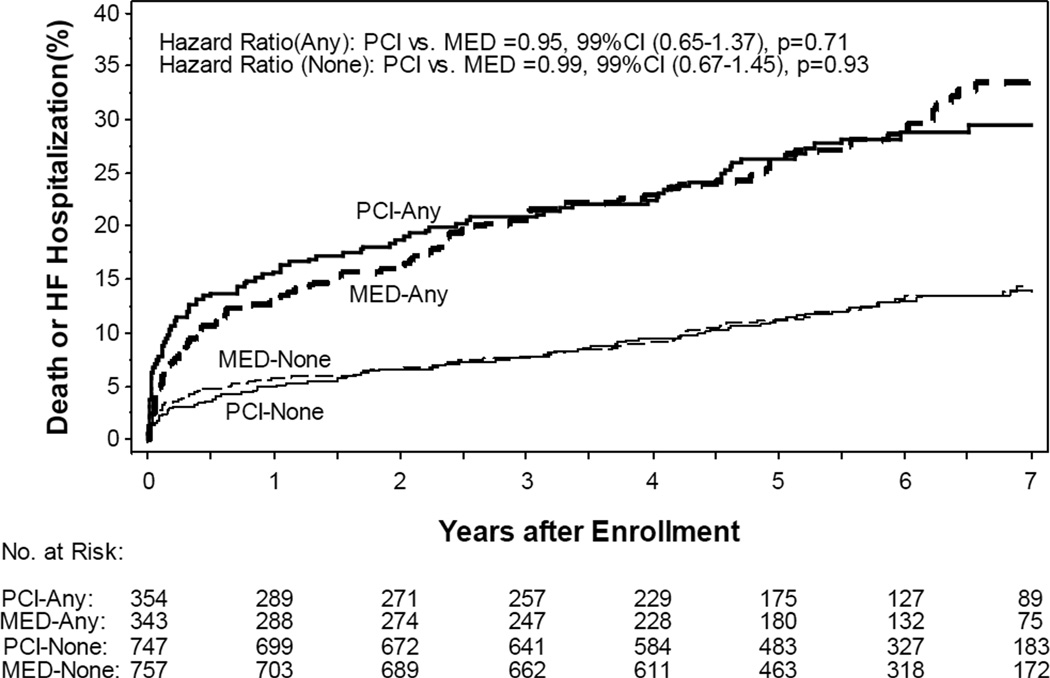

Adjudicated HF hospitalization and all cause mortality risk by history of baseline heart failure

Among the 2201 patients in the study, 52 (2.4%) had a prior history of HF, 417 (18.9%) were in Killip class > 1 during index MI, 137 (6.2%) had rales on the intake physical exam, 38 (1.7%) had an S3 gallop on the intake physical exam, 367 (16.7%) were in NYHA II at time of randomization, and 259 (11.8%) had NYHA > 1 symptoms prior to the index MI. There were 89 adjudicated HF hospitalizations among the 697 patients with baseline HF (7-year estimated life-table rate: 13.6%) and 61 adjudicated HF hospitalizations among the 1504 patients without baseline HF (7-year estimated life-table rate: 4.7%). Baseline HF was associated with increased risk of adjudicated HF hospitalization (HR 3.43, 99% CI 2.23–5.26, p<0.0001) with no difference between the randomized groups (Figure 1). There were 153 deaths among the 697 patients with baseline HF (7-year estimated life-table rate: 24.7%) and 150 deaths among the 1504 patients without baseline HF (7-year estimated life-table rate: 10.8%). Baseline HF was associated with increased the risk of death (HR 2.31, 99% CI 1.71–3.1, p<0.001). Baseline HF increased the risk of the combined outcome of death or adjudicated HF hospitalization (7-year estimated life-table event rates: 31.9% vs. 14.2%, HR 2.45, 99% CI 1.89–3.18, p<0.001) with no difference between the randomized groups (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier plot of cumulative risk of adjudicated heart failure (HF) hospitalization by randomized group and by the presence of baseline HF features (Bolded solid and dashed lines “ANY” – with baseline HF; Non-bolded solid and dashed lines “NONE”– without baseline HF)

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier plot of cumulative risk of adjudicated heart failure (HF) hospitalization or death by randomized group and by the presence of baseline HF features(Bolded solid and dashed lines “ANY” – with baseline HF; Non-bolded solid and dashed lines “NONE” – without baseline HF)

Adjudicated HF hospitalization risk and all cause mortality risk by ejection fraction at study entry

449 of 2185 (21%) patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) data available had an EF < 40%. Among this group, the 7-year life-table event rate for adjudicated HF hospitalization was 18.0% compared to 4.9% for patients with an EF ≥40% (p<0.001). The 7-year life-table event rate for the combined outcome of death or adjudicated HF hospitalization was 37.6% for EF < 40% compared to 15.3% for EF ≥40% (p<0.001).

Predictors of adjudicated HF hospitalization

Table 3 lists hazard ratios and associated 99% confidence intervals for independent predictors of adjudicated HF hospitalization. For all 2201 patients, lower EF, increased age, history of diabetes, presence of at least 1 baseline HF feature, and peripheral vessel disease were significantly associated with increased risk of adjudicated HF hospitalization in multivariate analysis. There was a trend toward independent association of female sex with adjudicated HF hospitalization (HR 1.66 99% CI 0.95–2.90), p=0.0186). Among the 697 patients with baseline HF characteristics, lower EF, increased age, and peripheral vessel disease were significantly associated with increased risk of adjudicated HF hospitalization in multivariate analysis. Among the 1504 patients without baseline HF characteristics, increased age, lower left ventricular ejection fraction, and a history of diabetes mellitus were significantly associated with increased risk for adjudicated HF hospitalization in multivariate analysis.

Table 3.

Multivariate correlates of adjudicated HF hospitalization

| Predictors of NYHA III–IV HF events in ALL patients (n=2201, events=150) |

Hazard Ratio | 99% Confidence Interval |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF (decrease by 10%) | 1.68 | 1.40–2.01 | <0.0001 |

| Age (increase by 10yr) | 1.44 | 1.17–1.77 | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes history | 2.09 | 1.35–3.24 | <0.0001 |

| At least 1 baseline HF feature | 2.12 | 1.36–3.33 | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral vessel disease | 2.20 | 1.10–4.39 | 0.0032 |

|

Predictors of NYHA III-IV HF events in patients without baseline HF (n=1504, 61 events) |

|||

| LVEF (decrease by 10%) | 1.6 | 1.17–2.18 | 0.0001 |

| Age (increase by 10yr) | 1.59 | 1.16–2.18 | 0.0001 |

| Diabetes history | 3.22 | 1.64–6.32 | <0.0001 |

|

Predictors of NYHA III-IV HF events in patients with baseline HF (n=697, 89 events) |

|||

| LVEF (decrease by 10%) | 1.74 | 1.39–2.18 | <0.0001 |

| Age(increase by 10yr) | 1.35 | 1.04–1.77 | 0.0034 |

| Peripheral vessel disease history | 2.38 | 1.00–5.71 | 0.01 |

Baseline variables that entered the multivariate model include demographic and clinical characteristics listed in table 1, family history of coronary artery disease, heart rate (every 10 beats/min), systolic BP (every 10 mmHg decrease), diastolic BP (every 10 mmHg decrease), pulse pressure (every 10 mmHg decrease), GFR (every 10 ml/min/1.73 m2 decrease), glucose (every 10mg/dL), BMI, NYHA functional class > I during index MI or prior to randomization, clinical characteristics at index event (S3, Killip class > I, rales, new Q waves, ST elevations, R wave loss, ST elevations or new Q waves, ST elevations or Q waves, or R wave loss, thrombolytic use in first 24 hours, time to index MI (every 1 day increase), angiographic data listed in table 1, left ventricular ejection fraction (every 10% decrease), and the presence of at least 1 baseline HF feature.

Discussion

This study shows that approximately 7.5% of patients with an infarct-related occluded artery treated with guideline-recommended secondary prevention therapies experienced an adjudicated HF hospitalization within 9 years, that the occurrence of HF hospitalization did not differ between OAT treatment groups, that HF hospitalization is associated with a high risk of subsequent death, and that baseline heart failure at the time of the index MI event confers a greater risk of subsequent death and HF hospitalization. The estimated rate of adjudicated HF hospitalization reported here is lower than anticipated based on the entry criteria for OAT. This is a novel observation that is likely related to distinctive clinical characteristics of the OAT population and the high use of optimal medical therapy post MI in OAT.

Reperfusion of hibernating myocardium has been hypothesized to improve ejection fraction and indices of myocardial contractility after delayed opening of an occluded artery up to 16 days following infarction. A substudy of SAVE (Survival and Ventricular Enlargement) study found that 51% of patients with an occluded artery post MI experienced cardiovascular mortality or morbidity, including severe HF requiring hospitalization over an average 3.5 years.13 SAVE patients with an occluded artery who underwent revascularization had less cardiovascular mortality and morbidity than those who did not undergo revascularization.13 Two substudies of the randomized OAT study - TOSCA-2 and the OAT NUC viability study, which examined the effect of recanalization of a persistently occluded infarct-related artery on indices of LV size and function, contrast with the findings reported in SAVE and subsequent meta-analysis. 18, 19, 20 Both found that ejection fraction improves significantly and equally over one year with either PCI of an occluded artery or optimal medical therapy alone.19, 20 In the subgroup of 449 patients with EF < 40%, event rates were lower than that reported in the SAVE population, with 37.6% of patients experiencing death or HF hospitalization over 7 years of follow-up.

Other post-MI clinical trials have reported higher rates of HF during follow-up compared with the present study. In a large subgroup of stable VALIANT patients without a history of HF, 10.3% developed HF requiring hospitalization over a median 25-month follow-up.21 VALIANT specifically enrolled patients with MI complicated by heart failure or with LV systolic dysfunction defined as an EF < 35%.8 The Carvedilol Post-Infarct Survival Control in LV Dysfunction Study (CAPRICORN) reported a HF hospitalization rate of 12% among the group randomized to carvedilol therapy over a mean of 16 months follow-up.10 CAPRICORN enrolled patients with MI and an EF < 40%.10 The Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study (EPHESUS) reported a HF hospitalization rate of 10% among patients randomized to eplerenone over mean of 16 months.12 EPHESUS also used an ejection fraction less than 40% with evidence of HF for non-diabetic patients as an inclusion criterion.12

The higher incidence of HF hospitalization in VALIANT, CAPRICORN, and EPHESUS compared to OAT is likely related to differences in clinical characteristics of the study samples as determined by the selection criteria of each study. The majority of HF hospitalizations in OAT involved patients with reduced EF. The average EF of 48% among OAT patients is substantially higher than these other studies. However, the 7-year life-table event rate for HF hospitalization among OAT patients with an EF < 40% (18.0%) is less than the trials listed above. Notably, even among patients in a known higher-risk group of Killip class > I at index MI, 87% did not have a centrally confirmed HF hospitalization in follow–up. OAT investigators have previously reported that OAT patients in the lowest EF tertile (EF < 44%) had a higher incidence of the primary outcome as well as its individual components.22 Although the selection for persistent total occlusion of the infarct related artery was expected to increase the risk for HF hospitalization and mortality, the exclusion of patients with other higher-risk features (NYHA III or IV HF at time of enrollment, left main or three-vessel coronary disease, post-infarct angina, severe ischemia on stress testing, or severe valvular disease) from OAT may have contributed to the lower rate of HF hospitalization seen in OAT even among the low-EF subset. The relatively low average age of the OAT population and the low prevalence of multivessel disease may have also contributed to the low observed rate of HF hospitalization.

Beta blocker use has been to shown to improve the function of hibernating myocardium in ischemic cardiomyopathy.23 In VALIANT, 70% of patients used beta-blockers and 99% used valsartan, captopril, or both. In CAPRICORN, 50% of patients used carvedilol and 98% used ACE-inhibitors at the time of randomization. In EPHESUS, 75% of patients used beta-blockers and 87% used either ACE-inhibitors or ARBs at baseline. A higher proportion of OAT patients used beta-blockers (88%) than the trials listed. Overall angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker use in OAT (80%) was lower than the trials listed but among OAT patients with comparable EF (<40%), ACE-I or ARB use was comparable (92%).

Our data demonstrate that there was an initial period of increased HF hospitalization risk in the first 12 months after enrollment and subsequent lesser risk of first HF events during the remainder of follow-up. It should be noted that the rates of HF or death continue to rise over time, in contrast to the rates of new HF. These are time-to-first-event analyses and therefore this suggests increasing rates of death or HF in later years of follow up were due mostly to deaths among patients not already hospitalized for HF.

In OAT, the choice of treatment strategy (PCI and optimal medical therapy vs. optimal medical therapy alone) did not affect the incidence of adjudicated HF hospitalizations. The major predictors of adjudicated NYHA HF hospitalization in OAT were patient characteristics prior to the index MI and the presence of HF features at the time of MI. Independent predictors of adjudicated HF hospitalization post-MI included lower EF, older age, diabetes, baseline HF factors, and peripheral arterial disease. These variables are comparable to those identified in VALIANT and CARE.21, 24

There are several limitations of this analysis. OAT was a randomized, controlled trial investigating the possible benefit of opening an infarct-related artery post-MI. We now report a pre-specified but post-hoc non-randomized subgroup analysis of original data. To reduce the chance of spurious findings associated with multiple comparisons across various OAT substudy populations, we used a conservative p-value <0.01 to infer statistical significance in our analysis. Although the clinical characteristics of the OAT population were very well characterized at study entry, we cannot rule out the possibility that unmeasured confounders may have contributed to our findings. The predictors of poor outcome identified in this population are largely comparable to those reported in past studies, but the overall event rates are lower than previous studies. Whether this lower event rate is attributable to background medical therapy or other unique characteristics of the OAT population cannot be determined from the present analysis. Although the study protocol incorporated active surveillance for heart failure hospitalizations, less severe heart failure events may not been captured. New prescriptions for diuretics in 19.2% of subjects indicates that some new heart failure events not requiring hospitalization may have occurred. Several features of the OAT patient population suggest that the observed incidence of post-MI HF reported here may not be generalized to all post-MI patients. The average time between MI to randomization in OAT was 8 days; this time delay may have selected for a lower risk group of patients compared to groups in previous clinical trials. Enrollment in any clinical trial inevitably introduces some degree of referral bias that may select a lower risk group of patients. Despite the lower rates of HF hospitalization in this population, HF hospitalization was associated with significant risk of subsequent mortality. In addition, baseline HF was associated with subsequent mortality; this has been found in a large, retrospective observational study by Torabi et al.25 Mortality was not affected by revascularization in OAT. In addition, the results of two randomized controlled trials of revascularization in heart failure, STICH and HEART, suggest a neutral effect of revascularization on overall mortality in patients with coronary artery disease and heart failure.26, 27 These findings emphasize the importance of optimal medical therapy post-MI to prevent HF development even in a clinical trial population that may have been lower risk than other post-MI clinical populations or clinical practice

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who enrolled in the study, their physicians, and the staff at the study sites for their important contributions; and Carole Russo, for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding Sources:

The project described was supported by Award Numbers U01 HL062509 and U01 HL062511 from the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health. Supplemental grant funds and product donations equivalent to 6% of total study cost were received from: Eli Lilly, Millennium Pharmaceuticals and Schering Plough, Guidant, Cordis/Johnson and Johnson, Medtronic, Merck and Bristol Myers Squibb Medical Imaging.

Judith S. Hochman: Dr. Hochman received grant support to her institution from Eli Lilly and Bristol Myers Squibb Medical Imaging and product donation from Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Schering-Plough, Guidant, and Merck for OAT and received consultation fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, honoraria for Steering Committee service from Eli Lilly and Glaxo Smith Kline and honoraria for serving on the Data Safety Monitoring Board of a trial supported by Merck Co.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

NIH PubMed Central Policy:

We request the journal to acknowledge that the Author retains the right to provide a copy of the final manuscript to the NIH upon acceptance for Journal publication, for public archiving in PubMed Central as soon as possible but no later than 12 months after publication by Journal.

Disclosures:

Rahul R. Jhaveri: none

Harmony R. Reynolds: none

Stuart D. Katz: Dr. Katz serves as a consultant for Bristol Meyers Squibb, Amgen Inc. and Terumo Heart. He is a speaker for Otsuka Pharmaceuticals.

Raban Jeger: none

Elzbieta Zinka: none

Sandra A. Forman: none

Gervasio A. Lamas: Dr. Lamas is a speaker for Novartis, GlaxoSmith Kline, CVT and Astra-Zeneca. Dr. Lamas also has modest ownership interest in GDS. He serves as a consultant for CVT and Astra-Zeneca.

References

- 1.Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, Dzavík V, Buller CE, Ruzyllo W, Sadowski ZP, Maggioni AP, Carvalho AC, Rankin JM, White HD, Goldberg S, Forman SA, Mark DB, Lamas GA for the Occluded Artery Trial Investigators. Long-Term Effects of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention of the Totally Occluded Infarct-Related Artery in the Subacute Phase After Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2011 Nov 22;124(21):2320–2328. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.041749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weir RAP, McMurray JJV, Velazquez EJ. Epidemiology of heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction after acute myocardial infarction: prevalence, clinical characteristics, and prognostic importance. Am. J. Cardiol. 2006;22:13F–25F. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleland JGF, Torabi A, Khan NK. Epidemiology and management of heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction in the aftermath of a myocardial infarction. Heart. 2005;91(Suppl 2):ii7–ii13. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.062026. discussion ii31, ii43–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Velagaleti RS, Pencina MJ, Murabito JM, Wang TJ, Parikh NI, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Kannel WB, Vasan RS. Long-Term Trends in the Incidence of Heart Failure After Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2008;118:2057–2062. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.784215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hellermann JP, Jacobsen SJ, Redfield MM, Reeder GS, Weston SA, Roger VL. Heart failure after myocardial infarction: clinical presentation and survival. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2005;7:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hellermann JP, Goraya TY, Jacobsen SJ, Weston SA, Reeder GS, Gersh BJ, Redfield MM, Rodeheffer RJ, Yawn BP, Roger VL. Incidence of heart failure after myocardial infarction: is it changing over time? Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003;157:1101–1107. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg RJ, Spencer FA, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Gore JM, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. A 25-year perspective into the changing landscape of patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction (the Worcester Heart Attack Study) The American Journal of Cardiology. 2004;94:1373–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.07.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, Rouleau J, Kober L, Maggioni AP, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Van de Werf F, White H, Leimberger JD, Henis M, Edwards S, Zelenkofske S, Sellers MA, Califf RM Valsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial Investigators. Valsartan, Captopril, or Both in Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Heart Failure, Left Ventricular Dysfunction, or Both. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(20):1893–1906. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, Moyé LA, Basta L, Brown EJ, Cuddy TE, Davis BR, Geltman EM, Goldman S, Flaker GC, Klein M, Lamas GA, Packer M, Rouleau J, Rouleau JL, Rutherford J, Wertheimer JH, Hawkins CM on behalf of the SAVE Investigators. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:669–677. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dargie HJ. Effect of carvedilol on outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with left-ventricular dysfunction: the CAPRICORN randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1385–1390. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04560-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buch P, Rasmussen S, Abildstrom SZ, Køber L, Carlsen J, Torp-Pedersen C. The long-term impact of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor trandolapril on mortality and hospital admissions in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after a myocardial infarction: follow-up to 12 years. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:145–152. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, Neaton J, Martinez F, Roniker B, Bittman R, Hurley S, Kleiman J, Gatlin M Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study Investigators. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1309–1321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamas GA, Flaker GC, Mitchell G, Smith SC, Jr, Gersh BJ, Wun CC, Moyé L, Rouleau JL, Rutherford JD, Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E for the Survival Ventricular Enlargement Investigators. Effect of Infarct Artery Patency on Prognosis After Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 1995;92:1101–1109. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochman JS, Lamas GA, Buller CE, Dzavik V, Reynolds HR, Abramsky SJ, Forman S, Ruzyllo W, Maggioni AP, White H, Sadowski Z, Carvalho AC, Rankin JM, Renkin JP, Steg PG, Mascette AM, Sopko G, Pfisterer ME, Leor J, Fridrich V, Mark DB, Knatterud GL Occluded Artery Trial Investigators. Coronary intervention for persistent occlusion after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2395–2407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hochman JS, Lamas GA, Knatterud GL, Buller CE, Dzavik V, Mark DB, Reynolds HR, White HD Occluded Artery Trial Research Group. Design and methodology of the Occluded Artery Trial (OAT) Am. Heart J. 2005;150:627–642. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Mann JT, Fry ETA, DeLago A, Wilmer C, Topol EJ CREDO Investigators. Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation. Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2411–2420. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345:494–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Appleton DL, Abbate A Biondi-Zoccai GGL. Late percutaneous coronary intervention for the totally occluded infarct-related artery: a meta-analysis of the effects on cardiac function and remodeling. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;71:772–781. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dzavík V, Buller CE, Lamas GA, Rankin JM, Mancini GBJ, Cantor WJ, Carere RJ, Ross JR, Atchison D, Forman S, Thomas B, Buszman P, Vozzi C, Glanz A, Cohen EA, Meciar P, Devlin G, Mascette A, Sopko G, Knatterud GL, Hochman JS TOSCA-2 Investigators. Randomized trial of percutaneous coronary intervention for subacute infarct-related coronary artery occlusion to achieve long-term patency and improve ventricular function: the Total Occlusion Study of Canada (TOSCA)-2 trial. Circulation. 2006;114:2449–2457. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.669432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Udelson JE, Pearte CA, Kimmelstiel CD, Kruk M, Kufera JA, Forman SA, Teresinska A, Bychowiec B, Marin-Neto JA, Höchtl T, Cohen EA, Caramori P, Busz-Papiez B, Adlbrecht C, Sadowski ZP, Ruzyllo W, Kinan DJ, Lamas GA, Hochman JS. The Occluded Artery Trial (OAT) Viability Ancillary Study (OAT-NUC): Influence of infarct zone viability on left ventricular remodeling after percutaneous coronary intervention versus optimal medical therapy alone. Am. Heart J. 2011;161:611–621. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis EF, Velazquez EJ, Solomon SD, Hellkamp AS, McMurray JJV, Mathias J, Rouleau JL, Maggioni AP, Swedberg K, Kober L, White H, Dalby AJ, Francis GS, Zannad F, Califf RM, Pfeffer MA. Predictors of the first heart failure hospitalization in patients who are stable survivors of myocardial infarction complicated by pulmonary congestion and/or left ventricular dysfunction: a VALIANT study. Eur. Heart J. 2008;29:748–756. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruk M, Buller CE, Tcheng JE, Dzavík V, Menon V, Mancini GB, Forman SA, Kurray P, Busz-Papiez B, Lamas GA, Hochman JS. Impact of left ventricular ejection fraction on clinical outcomes over five years after infarct-related coronary artery recanalization (from the Occluded Artery Trial [OAT]) Am. J. Cardiol. 2010;105:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.08.644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cleland JG, Pennell DJ, Ray SG, Coats AJ, Macfarlane PW, Murray GD, Mule JD, Vered Z, Lahiri A Carvedilol hibernating reversible ischaemia trial: marker of success investigators. Myocardial viability as a determinant of the ejection fraction response to carvedilol in patients with heart failure (CHRISTMAS trial): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362:14–21. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13801-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis EF, Moye LA, Rouleau JL, Sacks FM, Arnold JO, Warnica J, Flaker GC, Braunwald E, Pfeffer MA CARE Study. Predictors of late development of heart failure in stable survivors of myocardial infarction: The CARE study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1446–1453. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)01057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torabi A, Cleland JG, Khan NK, Loh PH, Clark AL, Alamgir F, Caplin JL, Rigby AS, Goode K. The timing of development and subsequent clinical course of heart failure after a myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:859–870. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Deja MA, Jain A, Sopko G, Marchenko A, Ali IS, Pohost G, Gradinac S, Abraham WT, Yii M, Prabhakaran D, Szwed H, Ferrazzi P, Petrie MC, O'Connor CM, Panchavinnin P, She L, Bonow RO, Rankin GR, Jones RH, Rouleau JL STICH Investigators. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1607–1616. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cleland JG, Calvert M, Freemantle N, Arrow Y, Ball SG, Bonser RS, Chattopadhyay S, Norell MS, Pennell DJ, Senior R. The Heart Failure Revascularisation Trial (HEART) Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:227–233. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]