Summary

The mechanisms underlying neurologic deficits and delayed neuronal death after ischemia are not fully understood. In the present study, we report that transient cerebral ischemia induces accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins (ubi-proteins) in postsynaptic densities (PSDs). By immuno-electron microscopy, we demonstrated that ubi-proteins were highly accumulated in PSD structures after ischemia. On Western blots, ubi-proteins were markedly increased in purified PSDs at 30 minutes of reperfusion, and the increase persisted until cell death in the CA1 region after ischemia. In the resistant DG area, however, the changes were transient and significantly less pronounced. Deposition of ubi-proteins in PSDs after ischemia correlates well with PSD structural damage in the CA1 region as viewed by electron microscopy. These results suggest that the ubiquitin-proteasome system fails to repair and remove damaged proteins in PSDs. The changes may demolish synaptic neurotransmission, contribute to neurologic deficits, and eventually lead to delayed neuronal death after transient cerebral ischemia.

Keywords: Ubiquitin, Brain ischemia, Postsynaptic density, Electron microscopy

Ubiquitin is a small 76 amino acid polypeptide found in all eukaryotic cells either free or covalently bound to other proteins. Conjugation of ubiquitin to proteins involves a series of ATP-dependent enzymatic reactions to form isopeptidyl bonds ligating ubiquitin to the proteins (ubi-proteins) (for a review, see Pickart, 2001). Ubiquitin tags proteins mostly for degradation by the proteasome protease complexes and is involved in regulation of all essential cellular processes including development, signal transduction, and synaptic plasticity (Ciechanover et al., 2000; Ehlers, 2003).

The synapse is the basic neurotransmission unit and consists of a presynaptic terminal, synaptic cleft, and a specialized postsynaptic membrane associated closely with a postsynaptic density (PSD). The PSD is a cyto-skeletal network in which many signaling and scaffold proteins are anchored to interact with neurotransmitter receptors and to transfer synaptic signals to postsynaptic neurons (Kennedy, 1998). Accumulating evidence strongly suggests that synaptic growth, repair, and plasticity require much faster turnover of synaptic proteins in PSDs than previously estimated (Chapman et al., 1994; Ehlers, 2003; Hegde and DiAntonio, 2002). It has also recently been reported that the ubiquitin-proteasome system is responsible for removal of damaged PSD proteins (DiAntonio et al., 2001). The ubiquitin-proteasome system plays a key role in adapting PSD protein composition to synaptic activity (Ehlers, 2003). AMPA receptor surface expression is regulated by protein ubiquitination (Colledge et al., 2003). In Caenorhabditis elegans, ubiquitination of the glutamate receptor changes synaptic receptor densities (Burbea et al., 2002). In Drosophila, the ubiquitin-proteasome system regulates synaptic strength and growth (DiAntonio et al., 2001).

Transient forebrain ischemia leads to dramatic synaptic ultrastructural changes and synaptic deficits before delayed neuronal death takes place in CA1 pyramidal neurons (Ito et al., 1975; Kirino, 1982; Smith et al., 1984). Although mechanisms for neuronal death after transient ischemia are not fully understood, depletion of intracellular free ubiquitin and formation of ubi-proteins may be involved (Hayashi et al., 1991; Magnusson and Wieloch, 1989; Morimoto et al., 1996). In an earlier study, the authors performed two- and three-dimensional electron microscopic analyses of synapses selectively stained with ethanolic phosphotungstic acid in the hippocampus of rats subjected to 15 minutes of ischemia followed by various periods of reperfusion. PSDs from both area CA1 and the DG are thicker and irregular at the early reperfusion periods relative to sham-operated controls. A quantitative study indicates that the increase in thickness is both greater and more long-lived in area CA1 than in DG. Three-dimensional reconstructions of PSDs created using electron tomography demonstrate a destructive change in PSDs of CA1 dying neurons at 24 hours of reperfusion. To study factors leading to synaptic damage, we purified the PSD fraction from hippocampal tissues and studied deposition of PSD proteins after brain ischemia. We found that PSDs are severely damaged, which is accompanied by depletion of free ubiquitin and deposition of ubi-proteins in the PSDs. The synaptic damage may contribute to neurologic deficits and delayed neuronal death in CA1 neurons after transient cerebral ischemia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Leupeptin, pepstatin and aprotinin were purchased from Sigma (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Antibodies against free ubiquitin (Morimoto et al., 1996) and microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) were purchased from Sigma (polyclonal). A monoclonal antibody that recognizes both free ubiquitin and ubi-protein conjugates (Morimoto et al., 1996) was obtained from Chemicon (Temecula, CA, U.S.A). Peroxidase- or fluorescent-linked secondary antibodies were purchased from Sigma.

Animal model

All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee, University of Miami. Brain ischemia was produced using the 2-vessel occlusion (2VO) model in rats as described in our previous study (Hu et al., 1998). Briefly, male Wistar rats (250–300 g) were fasted overnight. Anesthesia was induced with 3% halothane followed by maintenance with 1% to 2% halothane in an oxygen/nitrous oxide (30/70%) gas mixture. Catheters were inserted into the external jugular vein, tail artery, and tail vein to allow blood sampling, arterial blood pressure recording, and drug infusion. An incision was made through the neck, and both common carotid arteries were encircled by loose ligatures. Blood gases were measured and adjusted to PaO2 > 90 mm Hg, PaCO2 35 to 45 mm Hg, and pH 7.35 to 7.45. Bipolar EEG was recorded during the procedure. Blood was withdrawn via the jugular catheter to produce a mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) of 50 mm Hg, and both carotid arteries were quickly clamped. Blood pressure was maintained at 50 mm Hg during the ischemic period by withdrawing or infusing blood through the jugular catheter. At the end of the ischemic period, the clamps were removed and the blood reinfused through the jugular catheter. In all experiments, brain temperature was maintained at 37°C. For biochemical studies, brains were obtained by freezing them in situ with liquid nitrogen (Pontèn et al., 1973). The hippocampal tissues were dissected at −12°C in a glove box. For electron microscopy, brains were perfused with ice-cold 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer. For confocal microscopy, brains were perfused with ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Sham-operated rats were subjected to the same surgical procedures but without induction of brain ischemia. A sham-operated control group and groups of 15 minutes of ischemia followed by 30 minutes, 4, 24, and 72 hours of reperfusion were used in this study. Each experimental group consisted of at least four rats.

Electron and immunoelectron microscopy

Coronal brain sections were cut at a thickness of 120 μm with a Vibratome through the level of the dorsal hippocampus and postfixed for 1 hour with 4% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). Sections were dehydrated in an ascending series of ethanol to 100% and stained for 50 minutes with 1% phosphotungstic acid (PTA) prepared by dissolving 0.1 g of PTA in 10 mL of 100% ethanol and adding 400 μL of 95% ethanol (Bloom and Aghajanian, 1998). The EPTA solution was changed once after a 20-minute interval during the staining. The sections were then further dehydrated in dry acetone and embedded in Durcupan ACM resin. The ultrathin sections (0.1 μm) were prepared and examined in a JEOL 100CX electron microscope.

Immuno-electron microscopy was performed upon postischemic and control brain tissues. Brains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde containing 0.1% glutaraldehyde and postfixed for 1 hour at 4°C. Hippocampal tissue blocks were cut with a Vibratome at a thickness of 50 μm. Brain sections were incubated first with an anti-ubiquitin antibody (Chemicon, MAB1510), then with a biotinylated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Amersham), and followed by incubation with an avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) solution (Vectastain ABC kits, Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, U.S.A.). After washing in PBS, brain sections were developed with the DAB solution until staining was optimal as examined by light microscopy. Brain sections were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, rinsed in distilled water, and stained with 1% aqueous uranyl acetate overnight. Tissue sections were then dehydrated in an ascending series of ethanol concentrations to 100%, followed by dry acetone, and embedded in Durcupan ACM resin. Sections were cut at a thickness of 0.1 μm and examined with a JEOL 100CX electron microscope.

Subcellular fractionation

The crude synaptosomal (P2), microsomal fraction (P3), and cytosolic fraction (S3) were prepared essentially according to the method described previously (Hu and Wieloch, 1994). Brain tissues were homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer (25 strokes) in 15 vol. of ice-cold homogenization buffer containing 15 mM Tris base-HCl pH 7.6, 1 mM DTT, 0.25 M sucrose, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.25 μg/mL pepstatin A, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, 2.5 μg/mL aproptonin, 0.5 mM PMSF, 2.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1 M Na3VO4, 50 mM NaF, and 2 mM sodium pyrophosphate. The homogenates were centrifuged at 800 g at 4°C for 10 minutes, and the supernatants were centrifuged at 10,000 g at 4°C for 15 minutes to obtain P2. The P2 supernatants were further centrifuged at 165,000 g at 4°C for 1 hour to obtain P3 and its supernatant (S3). P2 and P3 were resuspended in the homogenization buffer containing 0.1% Triton X100 (TX100). Part of the P2 pellet was further washed with the homogenization buffer containing 1% TX100 and 300 mM KCl and centrifuged at 25,000 g to obtain crude synaptic pellets. Protein concentration was determined by the micro-bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method of Pierce (Rockford, IL, U.S.A.).

Preparation of postsynaptic densities

Isolation of PSDs was performed according to the procedure of Carlin et al. (1980) except that sodium orthovanadate (0.1 mM) and protease inhibitors (10 μg/mL leupeptin, 5 μg/mLpepstain, 5 μg/mL, aprotinin, and 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) were included in all buffers. Briefly, hippocampal tissue samples were pooled from 4 rats (approximately 1 g) and homogenized with a Dunce homogenizer. The homogenate was subjected to centrifugation to obtain the P2 fraction as described in the subcellular fractionation previously in this article. This P2 fraction was loaded onto a sucrose density gradient of 0.85M/1.0M/1.2M and centrifuged at 82,500 g for 2 hours at 4°C. The light membrane (LM) fraction was obtained from the 0.85/1.0 sucrose interface, and the synaptosomal fraction was collected from the 1.0M/1.2M sucrose interface. After washing with 1% Triton X100, synaptosomal pellets were collected by centrifugation and then subjected to a second 1.0M/1.5M/2.0M sucrose density gradient centrifugation at 201,000 g, 4°C for 2 hours. The isolated PSD fraction was obtained from the 1.5M/2.0M interface of the sucrose gradients. The PSD fraction was diluted with an equal volume of 1% Triton X-100/300 mM KCl solution, mixed for 5 minutes, and centrifuged at 275,000 g for 1 hour. The PSDs were suspended in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH7.4, 0.5 mM DTT, 100 mM KCl, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, 5 μg/mL pepstatin, 5 μg/mL aprotinin, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.2 mM sodium orthovanadate. A fraction of the PSDs was used for electron microscopic examination. The remaining portion of PSDs was dissolved in 0.3% SDS for biochemical analysis.

Laser-scanning confocal microscopy

Double-label fluorescence immunocytochemistry was performed with coronal brain sections (50 μm) from sham-operated control and animals subjected to 15 minutes of ischemia followed by 30 minutes, 2, 4, 24, and 72 hours of reperfusion. A rabbit polyclonal antibody against free ubiquitin (Sigma) and a mouse monoclonal antibody against microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP-2, Sigma) were used. The brain sections were washed twice in PBS for 5 minutes at room temperature (RT) and then in PBS containing 0.1% TX100 for 30 minutes. The sections were transferred into a 24-well microtiter plate filled with 1 mL of 0.01 M citric acid buffer (pH 6.0) and heated for less than 1 minute in a microwave set to 30% power. The sections were heated three times and then washed with PBS. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS/0.2% TX100 for 30 minutes. The primary antibodies were diluted 1:100 for polyclonal anti-free ubiquitin and 1:500 for monoclonal anti–MAP-2. After incubation with the primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, the sections were washed in PBS containing 0.1% TX100. The fluorescent secondary antibodies, fluorescein-labeled anti-rabbit and lissamine rhodamine-labeled anti-mouse, were diluted 1:250 and applied for 1 hour at RT. Sections were washed several times in PBS/0.1% TX100, mounted on glass slides, and coverslipped using Gelvatol. The slides were analyzed with a Zeiss laser-scanning confocal microscope.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was carried out on 17% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) for intracellular free ubiquitin in the S3 fraction and on 8% SDS-PAGE for remaining subcellular fractions (Hu et al., 1994). Equal amounts of samples containing 20 μg of protein in P2, 50 μg in S3, and 5 μg in the purified PSDs from the control group and experimental groups were applied to each lane in a slab gel of SDS-PAGE. Two different samples in each experimental group were run in parallel in each SDS-PAGE gel. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane. The membranes were incubated with a primary antibody that recognizes both free ubiquitin and ubi-proteins (Chemicon, 1:2,000), overnight at 4°C. The membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody for 45 minutes at RT. The blots were developed with an ECL detection method (Amersham). The films were scanned, and the optical densities of protein bands were quantified using Kodak 1D gel analysis Software. One-way ANOVA followed by Fischer’s PLSD post hoc test was used to assess statistical significance (P < 0.01).

RESULTS

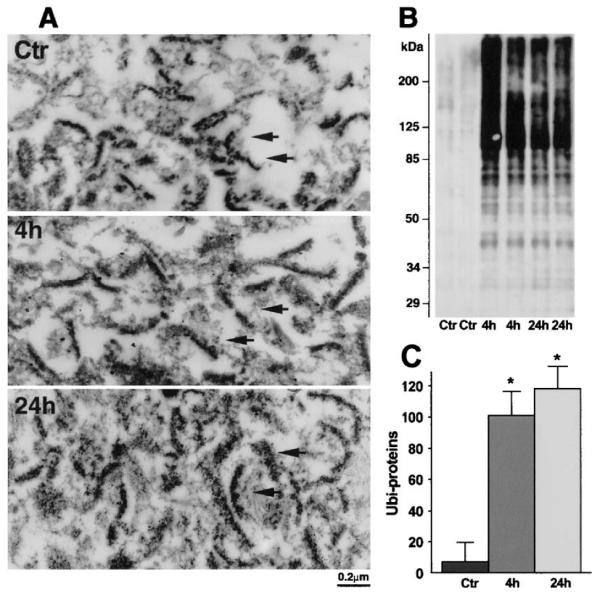

In a previous study, we found that PSD structures became thicker and more irregular, and there are destructive changes in CA1 neurons subjected to 15 minutes of ischemia followed by 24 hours of reperfusion (Hu et al., 1998; Martone et al., 1999). However, the morphology of these neurons at this postischemic stage looks perfectly normal under the light microsocopy (Siesjö and Bengtsson, 1989; Smith et al., 1984). To study possible pathologic factors related to PSD damage after brain ischemia, PSDs were isolated from sham-operated controls (Ctr) and from postischemic hippocampal tissues. A portion of isolated PSD preparations was examined by electron microscopy (Fig. 1A). The other portion wasused for biochemical analysis. Isolated PSDs from controls were small and often curved (Fig. 1A), whereas PSDs isolated from postischemic hippocampal tissues were larger in size (Fig. 1A). The changes in isolated postischemic PSDs are consistent with the alterations of PSD structures seen in brain sections reported previously (Hu et al., 1998; Martone et al., 1999). The isolated PSD fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting with ubiquitin antibody (Fig. 1B). Ubi-proteins were hardly detected in control PSDs but were significantly increased in isolated PSDs from postischemic hippocampal tissues subjected to 15 minutes of ischemia followed by 4 and 24 hours of reperfusion, respectively (Figs. 1B and 1C).

FIG. 1.

(A) Electron micrographs of PSDs isolated from hippocampal tissue. Isolated PSDs from control rats (Ctr) are small and often curved, whereas PSDs at 24 hours of reperfusion are larger in size (arrows). (B) Immunoblots of ubi-proteins in PSDs. PSDs were prepared from sham-control rats (Ctr) and rats subjected to 15 minutes of ischemia followed by 4 and 24 hours of reperfusion, respectively. The blots were labeled with the anti-ubi-protein antibody and visualized with an ECL system. Molecular sizes are indicated on the left. (C) Quantification of ubi-proteins on PSD Western blots with Kodak 1D image software. Mean optical intensities of immunoblot bands are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 4). *P < 0.01 between control and experimental conditions. One-way ANOVA followed by Fischer’s PLSD post hoc test was used to assess statistical significance. PSD, postsynaptic density; ubi-proteins, ubiquitinated proteins.

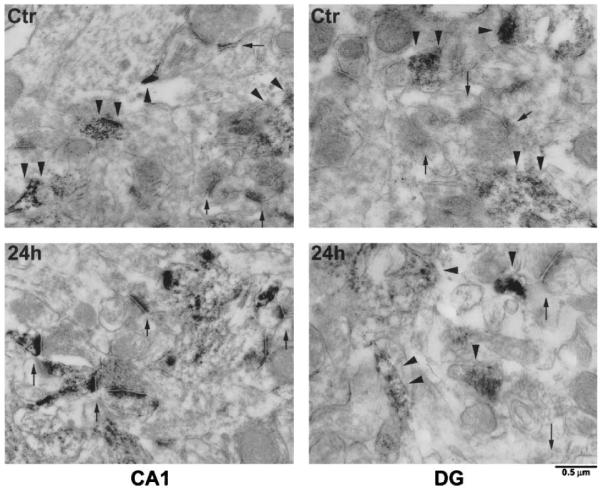

The distribution of ubiquitin immunoreactivity in brain sections was further studied by immuno-electron microscopy (Fig. 2). Ubiqutin immunolabeling in control CA1 and DG regions (Ctr) was distributed in soma (data not shown) and dendrites (Fig. 2), but was rarely found in PSDs (Fig. 2). However, ubiquitin immunolabeling was more concentrated in postischemic CA1 PSD structures in rats subjected to 15 minutes of ischemia followed by 24 hours of reperfusion (Fig. 2). In comparison, ubiquitin immunolabeling was not mainly distributed in postischemic DG PSD structures (Fig. 2), but in the dendrites (Fig. 2) at 24 hours of reperfusion after ischemia. Negative controls in which the primary antibody was omitted showed no immuno-labeling in brain sections (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Immuno-electron micrographs of ubiquitin immunolabeling in the dendritic region of CA1 and DG sections from a sham-operated control rat and a rat subjected to 15 minutes of ischemia followed by 24 hours of reperfusion. The immunolabeling is distributed throughout dendrites in the CA1 and DG control (Ctr, arrowheads), as well as in the DG region after ischemia (DG, 24 hours, arrowheads) but is more concentrated in CA1 PSD structures after ischemia (CA1, 24 hours, arrows). Scale bar = 0.5 μm.

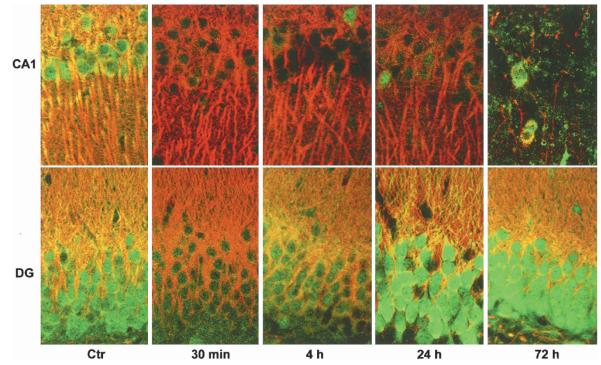

Depletion of free ubiquitin in hippicampal CA1 neurons after ischemia could be clearly seen by laser scanning confocal microscopy (Fig. 3). Brain sections were double-labeled with the polyclonal anti-free ubiquitin antibody from Sigma (Fig. 3) and monoclonal MAP-2 antibody (Fig. 3). Free ubiquitin immunostaining was evenly distributed in sham-control neurons but was severely and persistently depleted in dying CA1 neurons after ischemia (Fig. 3). In comparison, free ubiquitin immunostaining was moderately and transiently decreased at 30 minutes of reperfusion, then rebounded to a greater than control level at 24 hours of reperfusion after ischemia (Figs. 3 and 4). MAP-2 immunostaining in neuronal dendrites (Fig. 3) tended to decrease in CA1 neurons before 72 hours and was lost after 72 hours of reperfusion when severe cell loss was taking place in the CA1 region after 15 minutes of ischemia (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Double-staining confocal microscopic images of CA1 (upper) and DG (lower) regions. Brain sections were double-labeled with mouse anti-MAP-2 and rabbit anti-free ubiquitin antibodies. Sections are from sham-control (Ctr) rat and rats subjected to 15 minutes of ichemia followed by 30 minutes, 4, 24, and 72 hours of reperfusion, respectively. Free ubiquitin immunostaining (green color) is thoroughly depleted persistently in CA1 neurons after ischemia. MAP-2 immunlabeling is lost after 72 hours of reperfusion, indicative of delayed CA1 neuronal death after ischemia.

FIG. 4.

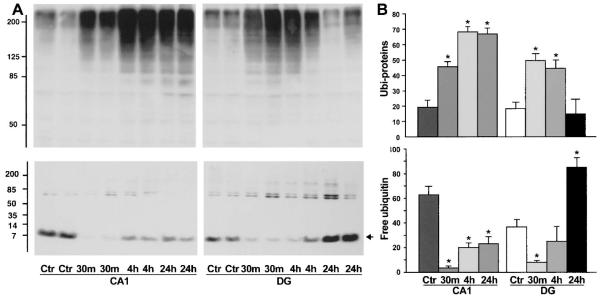

A) Immunoblots of ubiquitin in Triton-insoluble pellets (upper) and cytosol (S3, lower). Samples of hippocampal CA1 and DG were from sham-control rats (Ctr) and rats subjected to 15 minutes of ischemia followed by 30 minutes, 4, and 24 hours of reperfusion, respectively. Two separate samples derived from two rats in each experimental group were subjected to the SDS-PAGE. The blots were labeled with the anti-ubiquitin antibody and visualized with the ECL system. Molecular sizes are indicated on the left. (B) Changes in ubi-proteins in the synaptic pellets and cytosol were evaluated with Kodak 1D image software. Mean optical intensities of immunoblot bands are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 4). *P < 0.01 between control and experimental conditions. One-way ANOVA followed by Fischer’s PLSD post hoc test was used to assess statistical significance.

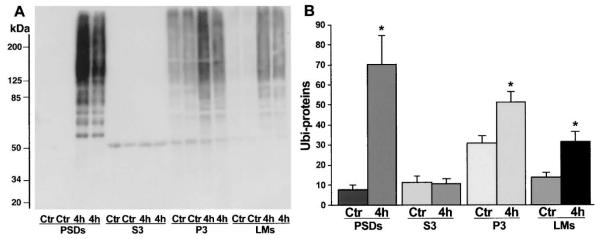

To correlate deposition of ubi-proteins into PSDs with neuronal vulnerability after brain ischemia, we dissected hippocampus into the vulnerable CA1 region and the resistant DG area to investigate deposition of ubi-proteins in CA1 and DG synaptic fractions by Western blotting. Because the dissected CA1 and DG tissues were too small in volume to purify PSDs, we treated the crude synaptosomal fraction with 1% Triton X100 (TX)/300 mM KCl to extract the contents of presynaptic terminals and lipid membranes. The resulted TX100/salt-washed crude pellets containing crude PSDs, mitochondria, and Triton-insoluble components were analyzed by Western blotting with the anti-ubi-protein antibody (Chemicon). Consistent with deposition of ubi-proteins in purified PSDs (Fig. 2), ubi-proteins were dramatically increased in the crude pellets from both CA1 and DG regions (Fig. 4A). However, the changes were more pronounced and lasted much longer in the CA1 region than in the DG area (Fig. 4B). Concomitantly, intracellular free ubiquitin in the cytosol was significantly decreased persistently in the CA1 neurons but transiently in the DG tissues after ischemia (Figs. 4A and 4B). These results indicate that free ubiquitin in the cytosol was used at least in part to form ubi-protein conjugates in the synaptic pellets. Relative to the changes in PSDs, ubi-proteins were more moderately increased in intracellular membranes (P3) and light cell membranes (LMs) but unchanged in cytosol (S3) after ischemia (Figs. 5A and 5B).

FIG. 5.

A) Immunoblots of ubi-proteins in postsynaptic densities (PSDs), cytosol (S3), intracellular membranes (P3) and light membranes (LM). Samples were prepared from sham-control rats (Ctr) and rats subjected to 15 minutes of ischemia followed by 4 h of reperfusion. The blots were labeled with the anti-ubi-protein antibody and visualized with the ECL system. Molecular sizes are indicated on the left. (B) Changes in ubi-proteins among subcellular fractions were evaluated with Kodak 1D image software. Mean optical intensities of immunoblot bands are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 4). *P < 0.01 between control and experimental conditions. One-way ANOVA followed by Fischer’s PLSD post hoc test was used to assess statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

Decrease in ubiquitin immunoreactivity in CA1 neurons after transient ischemia was first reported by Magnusson and Wieloch (1989). Later, several studies demonstrated that ubiquitin-protein conjugates (ubi-proteins) are highly increased after brain ischemia (Hayashi et al., 1992; Hu et al., 2000; Ide et al., 1999; Morimoto et al., 1996). The present study provides new evidence that ubi-proteins are predominantly accumulated in PSDs relative to other subcellular fractions after brain isch-emia, suggesting that postsynaptic structures are a major target for protein ubiquitination after transient cerebral ischemia. Ubi-proteins in postischemic PSDs are highly detergent- and salt-resistant, indicating that ubi-proteins are tightly deposited into PSDs. Because ubiquitin mainly tags damaged or unfolded proteins for degradation, accumulation of ubi-proteins in postischemic PSDs should reflect synaptic protein damage. This is consistent with the destructive PSD ultrastructural changes observed by electron microscopy (Martone et al., 1999). Ubi-proteins are predominately deposited in PSDs relative to other subcellular fractions, and they are accumulated more persistently and to a higher degree starting a couple of days before delayed cell death takes place in CA1 neurons after transient cerebral ischemia. This evidence supports the idea that PSD protein damage may contribute to neurologic deficits and delayed neuronal death.

How are synaptic proteins damaged and then ubiquitinated after transient ischemia? A recent study demonstrates that normal synaptic activity requires turnover of PSD proteins at a much faster pace than previously estimated (Ehlers, 2003). Removal of PSD proteins is carried out by the ubiquitin-proteosome system, which exclusively depends upon cellular ATP (Ciechanover et al., 2000). ATP is thoroughly depleted to an almost zero level during ischemia and throughout the early phase of reperfusion (Siesjö and Bengtsson, 1989). Therefore, protein ubiquitination and degradation come to a halt, so that PSD proteins that must be turned over are accumulated in the PSDs. In addition, other factors such as calcium-mediated calpain activation and reactive oxygen species production after ischemia are able to damage PSD proteins (e.g., the cleavage of spectrin after ischemia) (Franzon et al., 2003; Roberts-Lewis et al., 1994). Upon reperfusion, cellular ATP is gradually recovered during approximately 30 minutes to 1 hour of reperfusion so that the ubiquitin system starts to tag damaged PSD proteins. As a result, PSD proteins are highly ubiquitinated. However, proteasomal degradation capacity is overwhelmed by the large quantities of damaged cellular proteins produced during and after ischemia (Asai et al., 2002; Hu et al., 2000, 2001), and intracellular free ubiquitin are totally depleted in CA1 neurons throughout reperfusion (Fig. 3). In addition, degradation of ubi-proteins by proteasomes requires the assistance of molecular chaperones (Imai et al., 2003). We have previously shown that the constitutive heat-shock cognate protein 70, a major molecular chaperon, is highly deposited in PSDs after ischemia (Hu et al., 1998). These series of events indicate that the ubiquitin-proteasome system cannot normally operate to remove damaged PSD proteins after ischemia. As a result, ubi-proteins as well as chaperone proteins are deposited in PSD after transient brain ischemia.

Accumulation of ubi-proteins in PSDs reflects synaptic damage after ischemia. Synaptic damage should have functional consequences. Many earlier studies have shown that synapse transmission is damaged permanently in CA1 neurons after a brief period of ischemia but transiently in DG neurons (Auer et al., 1989; Dalkara et al., 1996; Escudero et al., 1998; Furukawa et al., 1990; Volpe et al., 1992; Xu, 1995). This is consistent with deposition of ubi-proteins in PSDs observed in the present study. We hypothesize that the ubiquitin-proteasome system is overwhelmed by large quantities of damaged proteins accumulated after ischemia (Hu et al., 2000), resulting in deposition of ubi-proteins in PSDs and leading to neurologic deficits. The ubiquitin-proteasome system after ischemia persistently fails and is unable to remove damaged proteins in PSDs to maintain neuronal homeostasis and thus will eventually lead to delayed neuronal death after brain ischemia.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant NS36810 to B.R.H.

REFERENCES

- Asai A, Tanahashi N, Qiu JH, Saito N, Chi S, Kawahara N, Tanaka K, Kirino T. Selective proteasomal dysfunction in the hippocampal CA1 region after transient forebrain ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:705–710. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200206000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer RN, Jensen ML, Whishaw IQ. Neurobehavioral deficits due to ischemic brain damage limited to half of the CA1 sector of the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1989;9:1641–1647. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-05-01641.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom FE, Aghajanian GK. Cytochemistry of synapses: Selective staining for electron microscopy. Science. 1968;154:1575–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.154.3756.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbea M, Dreier L, Dittman JS, Grunwald ME, Kaplan JM. Ubiquitin and AP180 regulate the abundance of GLR-1 glutamate receptors at postsynaptic elements in C elegans. Neuron. 2002;35:107–120. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00749-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlin RK, Grab DJ, Cohen RS, Siekevitz P. Isolation and characterization of postsynaptic densities from various brain regions: enrichment of different types of postsynaptic densities. J Cell Biol. 1980;86:831–845. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.3.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AP, Smith SJ, Rider CC, Beesley PW. Multiple ubiquitin conjugates are present in rat brain synaptic membranes and postsynaptic densities. Neurosci Lett. 1994;168:238–242. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanover A, Orian A, Schwartz AL. The ubiquitin-mediated proteolytic pathway: Mode of action and clinical implications. J Cell Biochem. 2000;77:40–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(2000)77:34+<40::aid-jcb9>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colledge M, Snyder EM, Crozier RA, Soderling JA, Jin Y, Langeberg LK, Lu H, Bear MF, Scott JD. Ubiquitination regulates PSD-95 degradation and AMPA receptor surface expression. Neuron. 2003;40:595–607. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalkara T, Ayaata C, Demirci M, Erdemli G, Onur R. Effects of cerebral ischemia on N-methyl-D-aspartate and dihydropyridine sensitive calcium currents: An electrophysiological study in the rat hippocampus in situ. Stroke. 1996;27:127–133. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiAntonio A, Haghighi AP, Portman SL, Lee JD, Amaranto AM, Goodman CS. Ubiquitination-dependent mechanisms regulate synaptic growth and function. Nature. 2001;412:449–452. doi: 10.1038/35086595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers MD. Activity level controls postsynaptic composition and signaling via the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Nat Neurosci. 2003;10:10. doi: 10.1038/nn1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escudero JV, Sancho J, Bautista D, Escudero M, Lopez-Trigo J. Prognostic value of motor evoked potential obtained by transcranial magnetic brain stimulation in motor function recovery in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1998;29:1854–1859. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.9.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzon R, Lamers ML, Stefanello FM, Wannmacher CM, Wajner M, Wyse AT. Evidence that oxidative stress is involved in the inhibitory effect of proline on Na,K-ATPase activity in synaptic plasma membrane of rat hippocampus. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2003;21:303–307. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(03)00076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K, Yamana K, Kogure K. Post-ischemic alterations of spontaneous activities in rat hippocampal CA1 neurons. Brain Res. 1990;530:257–260. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91292-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Takada K, Matsuda M. Changes in ubiquitin and ubiquitin-protein conjugates in the CA1 neurons after transient sublethal ischemia. Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1991;15:75–82. doi: 10.1007/BF03161057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Takada K, Matsuda M. Subcellular distribution of ubiquitin-protein conjugates in the hippocampus following transient ischemia. J Neurosci Res. 1992;31:561–564. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490310321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde AN, DiAntonio A. Ubiquitin and the synapse. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:854–861. doi: 10.1038/nrn961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu BR, Janelidze S, Ginsberg MD, Busto R, Perez-Pinzon M, Sick TJ, Siesjo BK, Liu CL. Protein aggregation after focal brain ischemia and reperfusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:865–875. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200107000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu BR, Martone ME, Jones YZ, Liu CL. Protein aggregation following transient cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3191–3199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-09-03191.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu BR, Park M, Martone ME, Fischer WH, Ellisman MH, Zivin JA. Assembly of proteins to postsynaptic densities after transient cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. 1998;18:625–633. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-02-00625.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu BR, Wieloch T. Tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in the rat brain following transient cerebral ischemia. J Neurochem. 1994;62:1357–1367. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62041357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide T, Takada K, Qiu JH, Saito N, Kawahara N, Asai A, Kirino K. Ubiquitin stress response in postischemic hippocampal neurons under nontolerant and tolerant conditions. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:750–756. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199907000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai J, Yashiroda H, Maruya M, Yahara I, Tanaka K. Proteasomes and molecular chaperones: Cellular machinery responsible for folding and destruction of unfolded proteins. Cell Cycle. 2003;2:585–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito U, Spatz M, Walker JT, Jr., Klatzo I. Experimental cerebral ischemia in mongolian gerbils. I. Light microscopic observations. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1975;32:209–223. doi: 10.1007/BF00696570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MB. Signal transduction molecules at the glutamatergic postsynaptic membrane. Brain Res Rev. 1998;26:243–257. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirino T. Delayed neuronal death in the gerbil hippocampus following ischemia. Brain Res. 1982;239:57–69. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90833-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson K, Wieloch T. Impairment of protein ubiquitination may cause delayed neuronal death. Neurosci Lett. 1989;96:264–270. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90389-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martone ME, Jones YZ, Young SJ, Ellisman MH, Zivin JA, Hu BR. Modification of postsynaptic densities after transient cerebral ischemia: A quantitative and three-dimensional ultrastructural study. Neurosci. 1999;19:1988–1997. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01988.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto T, Ide T, Ihara Y, Tamura A, Kirino T. Transient ischemia depletes free ubiquitin in the gerbil hippocampal CA1 neurons. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:249–257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickart CM. Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:503–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontèn U, Ratcheson RA, Salford L, Siesjö BK. Optimal freezing conditions for cerebral metabolites in rats. J Neurochem. 1973;21:1127–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1973.tb07567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts-Lewis JM, Savage MJ, Marcy VR, Pinsker LR, Siman R. Immunolocalization of calpain I-mediated spectrin degradation to vulnerable neurons in the ischemic gerbil brain. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3934–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-06-03934.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siesjö BK, Bengtsson F. Calcium fluxes, calcium antagonists, and calcium-related pathology in brain ischemia, hypoglycemia, and spreading depression: A unifying hypothesis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1989;9:127–140. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1989.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ML, Bendek G, Dahlgren N, Rosen I, Wieloch T, Siesjö BK. Models for studying long-term recovery following forebrain ischemia in the rat. A 2-vessel occlusion model. Acta Neurol Scand. 1984;69:385–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1984.tb07822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe BT, Davis HP, Towle A, Dunlap WP. Loss of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons correlates with memory impairment in rats with ischemic or neurotoxin lesions. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:457–464. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu ZC. Neurophysiological changes of spiny neurons in the rat neostriatum after transient forebrain ischemia: An in vivo intracellular recording and staining study. Neurosci. 1995;67:823–836. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]