Abstract

Developing chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) seeds 12 to 60 d after flowering (DAF) were analyzed for proteinase inhibitor (Pi) activity. In addition, the electrophoretic profiles of trypsin inhibitor (Ti) accumulation were determined using a gel-radiographic film-contact print method. There was a progressive increase in Pi activity throughout seed development, whereas the synthesis of other proteins was low from 12 to 36 DAF and increased from 36 to 60 DAF. Seven different Ti bands were present in seeds at 36 DAF, the time of maximum podborer (Helicoverpa armigera) attack. Chickpea Pis showed differential inhibitory activity against trypsin, chymotrypsin, H. armigera gut proteinases, and bacterial proteinase(s). In vitro proteolysis of chickpea Ti-1 with various proteinases generated Ti-5 as the major fragment, whereas Ti-6 and -7 were not produced. The amount of Pi activity increased severalfold when seeds were injured by H. armigera feeding. In vitro and in vivo proteolysis of the early- and late-stage-specific Tis indicated that the chickpea Pis were prone to proteolytic digestion by H. armigera gut proteinases. These data suggest that survival of H. armigera on chickpea may result from the production of inhibitor-insensitive proteinases and by secretion of proteinases that digest chickpea Pis.

In a co-evolving system of plant-insect interactions, plants synthesize a variety of toxic proteinaceous and nonproteinaceous molecules for their protection against insects (Ehrlich and Raven, 1964; Janzen, 1980; Ryan, 1990; Felton, 1996). At the same time, insects develop resistance to these phytochemicals by detoxification, thereby inactivating the plant's defense (Orr et al., 1994; Jongsma et al., 1995; Michaud et al., 1995, 1996; Broadway, 1996; Felton, 1996; Ishimoto and Chrispeels, 1996; Michaud, 1997). Proteinaceous inhibitors of proteinases and amylases serve as one of the defense mechanisms in plants against invading pests (Garcia-Olmedo et al., 1987; Ryan, 1990; Boulter, 1993). Expression of the cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) Ti gene in tobacco to increase its resistance against herbivorous insects was the first example of involvement of inhibitors in plant defense action (Hilder et al., 1987). It was followed by many similar studies in various plant species (Johnson et al., 1989; Boulter, 1993; McManus et al., 1994; Schroeder et al., 1995; Urwin et al., 1995; Duan et al., 1996; Michaud et al., 1996; Xu et al., 1996).

Some proteinaceous inhibitors of proteinases are constitutively expressed at high levels in storage organs and seeds, whereas others are induced in leaves by wounding. Mechanisms involved in wound inducibility of Pi in leaves of tomato and potato are well documented (Green and Ryan, 1972; Ryan and An, 1988; Jongsma et al., 1994; Peña-Cortés et al., 1995). Although wounding induces systemic Pi in species of the Solanaceae, Fabaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Solicaceae, and Poaceae (Schaller and Ryan, 1995), no reports are available on the synthesis of Pi in developing seeds of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Studies of the synthesis of Pi and amylase inhibitors during legume seed development have been reported for trypsin and papain inhibitors in cowpea (Carasco and Xavier-Filho, 1981; Fernandes et al., 1991), amylase inhibitors in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) (Pueyo et al., 1993), amylase inhibitors and Ti in pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan) (Ambekar et al., 1996; Giri and Kachole, 1997), and Cys Pi in soybean (Glycine max) (Botella et al., 1996; Zhao et al., 1996).

Chickpea is the world's third most important pulse crop (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1993) and India produces 75% of the world's supply. Insect predation results in severe losses in chickpea production annually. Most of the losses (up to 85%) are caused by the podborer (Helicoverpa armigera Hübner), a polyphagous pest of the developing seeds of several legume species. H. armigera feeding on chickpea begins at flowering and is greatest between 25 to 45 DAF. Typically, a single larva damages over five pods per day, leading to heavy losses in crop yield. Plant Ser Pi are known to affect the growth of herbivorous insects and may function as defensive agents against Lepidopteran pests such as Helicoverpa and Spodop-tera, which use Ser proteinases to digest their food proteins (Johnston et al., 1991; Purcell et al., 1992; Jongsma et al., 1995). Several reports indicate that plant Ser Pi significantly inhibit proteolytic activity of insect midguts (Broadway and Duffey, 1986; Hilder et al., 1987; Broadway, 1995, 1996). Studies on the accumulation of Pi during chickpea seed development and the interaction of these Pi with HGP are, therefore, important. Although biochemical properties of mature chickpea seed Pi and their nutritional significance have been studied in detail by several workers (Belew et al., 1975; Belew and Eaker, 1976; Smirnoff et al., 1976, 1979; Jibson et al., 1981; Sastry and Murray, 1987; Saini et al., 1992), the biological properties and significance of Pi during seed development have not been reported.

In this study we have used a simple, efficient, and highly sensitive gel-radiographic film-contact print method (Pichare and Kachole, 1994) to delineate the proteinase-Pi interaction in chickpea. We have identified seven isoforms of chickpea Pi and described their differential accumulation during seed development. We also determined that the Pi were synthesized prior to the accumulation of storage proteins. The induction of Pi in response to chewing by H. armigera larvae was demonstrated. In addition, the HGPs appear to selectively destroy the Pi found in the seed. These results provide a possible biochemical explanation for the enormous preharvest damage of chickpea by H. armigera despite the high Pi activity in the seeds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L. var PG-91028) flowers in an experimental field were tagged on the day they opened, and developing pods were harvested 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 DAF. Pods partially injured by podborer (Helicoverpa armigera) larvae in the plot were harvested separately and the larvae were removed from the partly injured pods. Shoots, leaves, and flowers were also harvested. Seeds were germinated in pots and cotyledons were harvested at 5, 10, 18, and 25 DAG. The harvested tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C. Frozen tissues were pulverized with a mortar and pestle and depigmented by washing at least six times with chilled acetone followed by hexane. Fine powders of the above tissues were obtained by filtration of acetone and hexane-washed material, followed by air drying.

Extraction of Chickpea Pi

Seed/tissue powder was extracted (with intermittent shaking at 5°C for 12 h) in 10 volumes (w/v) of distilled water or in 0.01 m Tris-HCl buffer, pH 6.8, containing 2.6 mm EDTA and the Pi leupeptin (1 μg/mL) and pepstain (1.4 μg/mL), which were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim. The suspension was centrifuged at 10,000g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected, and aliquots were frozen and stored at −20°C. The protein concentration of the extracts was quantified as described by Bradford (1976).

Extraction of HGPs

Third-instar larvae of H. armigera were dissected to isolate the midgut tissue, which was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C. The midgut tissue was homogenized and mixed with 0.1 m Tris-HCl buffer (1:3 w/v), pH 8.8, for 2 h at 10°C. The suspension was centrifuged at 4°C for 20 min at 10,000g and the resulting supernatant was used as a source of HGP. HGP solution was prepared fresh before use by extracting the frozen midguts.

Proteinase and Pi Assay

Proteinase activity was measured using a caseinolytic assay (Belew and Porath, 1970), as well as by using the synthetic substrate benzoyl-arginyl-p-nitro-anilide, as described by Erlanger et al. (1961). Pi activity was determined by mixing 15 μg of trypsin (7300 units/mg) (Sisco Research Laboratory, Bombay, India) or an equivalent amount of the other proteinases used in the study with sufficient amounts of the seed-extract-containing Pi to inhibit proteinase activity by 40 to 60%. The incubation of proteinase with Pi was conducted at 37°C for 10 min. The residual proteinase activity was measured using the caseinolytic assay. One unit of proteinase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that caused an increase of one optical density unit at 280 nm in the TCA-soluble products of casein hydrolysis per minute (Belew and Porath, 1970). One Pi unit was defined as the amount of inhibitor that inhibited 1 unit of proteinase activity.

Electrophoretic Analysis of Pi

Seed extracts or electrophoretially purified chickpea Ti were electrophoresed on a vertical slab gel using a discontinuous buffer system (Davis, 1964). After electrophoresis the gel was processed for activity staining of Pi by the gel-radiographic film-contact print method (Pichare and Kachole, 1994). The gel was incubated in 0.1 m Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.8, for 10 to 15 min, followed by incubation in the trypsin solution (0.1 mg/mL) for 15 min at 37°C on a shaking water bath. The gel was then washed with the same buffer and placed on a piece of undeveloped radiographic film. The gel was removed after 5 min, and hydrolysis of the gelatin was visually monitored.

Depending on the extent of gelatin hydrolysis, the film was washed with either tap or warm water (45°C). To detect bands with less Pi activity the same gel was overlaid three or more times with different pieces of radiographic film for 8, 12, and 20 min, respectively. Pi bands appeared as unhydrolyzed gelatin against the background of hydrolyzed gelatin. The reverse side of the film was cleared with trypsin, and the film was developed (IPC-163 developer, Kodak). After developing, the Pi bands on radiographic film became translucent against the dark, opaque background, which gave black bands on a white background on the photographic paper after contact printing.

Electrophoretic Purification of Chickpea Ti

Chickpea seed extracts (24 and 60 DAF) were electrophoresed on 12% preparative gels (Davis, 1964). A strip was cut for each gel and processed for Ti visualization. Corresponding Ti bands were excised from the gel, crushed, and eluted in 0.05 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 6.8, and inhibitor activity against trypsin was determined. Equal units of chickpea Ti-1, Ti-3, Ti-6, and Ti-7 were treated with trypsin (2 units) and reanalyzed by electrophoresis and gel assay to visualize active Ti fragments.

Treatment of Chickpea Ti with Proteinases

Electrophoretically purified chickpea Ti or seed homogenate extracts were incubated with the desired proteinases in the appropriate assay buffer: 0.1 m Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.8, for trypsin, chymotrypsin, and bacterial protease type XIV from Streptomyces griseus (Sigma); 0.1 m Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.8 and 8.8, for HGP; 0.05 m Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, containing 0.02 m EDTA and 0.05 m Cys for papain; and 0.1 m carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 10.0, for fungal proteinase from Conidiobolus sp. NCIM-86.8.20. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min and was analyzed on the polyacrylamide gel using the radiographic film-contact print method to determine the active Ti fragments.

Extracts of mature seeds (60 DAF) were incubated with varying concentrations of HGP or trypsin for 30 min at 37°C. The proteins remaining after digestion were resolved by SDS-PAGE (Laemmli, 1970) in the absence of 2-mercaptoethanol and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250.

Rearing of H. armigera Larvae on Developing Chickpea Seeds

Third-instar larvae were collected from the chickpea field and reared on developing seeds of chickpea for 3 to 4 d. Twenty-five larvae were individually placed in plastic containers with perforated caps (pin-holed), and reared on a supply of about 25 developing seeds of 36 and 48 DAF at 25°C. The resulting fecal matter was collected, washed with acetone and hexane, and dried at room temperature (25°C). The fine powder was extracted in 0.05 m Tris-HCl buffer, pH 6.8, and centrifuged, and the supernatant was concentrated and dialyzed against the same buffer. The dialyzed solution was analyzed for the presence of proteinase and Pi activity by solution assay and by activity staining after PAGE.

RESULTS

Chickpea Pi

Accumulation of Storage Proteins and Pi during Seed Development

The data shown in Table I indicate that the amount of total seed protein (storage protein) was relatively constant between 12 and 24 DAF, dramatically increased between 36 and 48 DAF, and reached 68.31 mg/g of seed meal by 60 DAF. Pi activity was detected for trypsin, chymotrypsin, and bacterial proteinases at 24 DAF, and the activity increased during seed development. Pi activity against HGPs was low at 36 and 48 DAF, but increased to 3 units by 60 DAF. Under identical assay conditions, the inhibition of casein hydrolysis by trypsin, chymotrypsin, and bacterial proteinases was greater than the inhibition of the HGP.

Table I.

Accumulation of total seed protein and activity during seed development

| DAF | Total Protein | Inhibitor

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti | Ci | HGPi | BPi | ||

| mg g−1 seed meal | units g−1 seed meal | ||||

| 12 | 5.64 | NDa | ND | ND | ND |

| 24 | 5.94 | 4.84 | 2.55 | ND | 0.54 |

| 36 | 8.99 | 11.22 | 2.60 | 0.32 | 1.17 |

| 48 | 38.80 | 14.52 | 5.56 | 0.17 | 1.94 |

| 60 | 68.31 | 19.62 | 9.45 | 3.00 | 3.39 |

The ability of chickpea seed extracts to inhibit trypsin (Ti), chymotrypsin (Ci), H. armigera gut proteinase (HGPi), and bacterial proteinase (BPi) was determined as described in Methods. Values are the averages of three replicates.

ND, Not detectable.

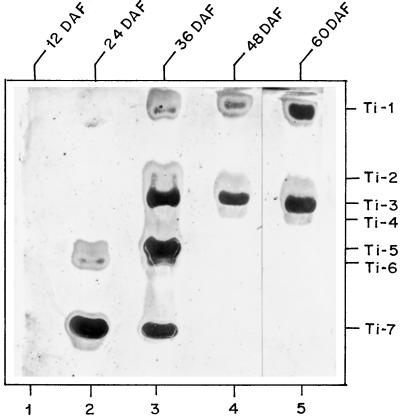

Differential Expression of Ti during Seed Development

Equal units of Ti activity at various stages of seed development were loaded onto electrophoretic gel to visualize Ti bands using the gel-radiographic film-contact print method (Fig. 1). Although 60 μg of protein was loaded onto the gel, no Ti activity was detected at 12 DAF (Fig. 1, lane 1). This confirms the solution assay data (Table I). Three Ti bands designated Ti-5, Ti-6, and Ti-7 were detected at 24 DAF (Fig. 1, lane 2). However, when 4-fold more protein was loaded, bands corresponding to Ti-3 and Ti-4 were also visible (results not shown). At 36 DAF, seven Ti bands (Ti-1–Ti-7) were detected (Fig. 1, lane 3), whereas at 48 and 60 DAF, only two major bands (Ti-1 and Ti-3) were present (Fig. 1, lanes 4 and 5). Chickpea Ti-1 remained in the stacking gel, entering the resolving gel only when the gel was electrophoresed for a longer period of time. The disappearance of Ti bands 5, 6, and 7 between 36 and 48 DAF appears to be a characteristic feature of chickpea Ti (Harsulkar et al., 1997).

Figure 1.

Differential expression of chickpea Ti during seed development. Ti activity was visualized using the gel-radiographic film technique described in Methods. Equal Ti units (0.03) of extracts of seeds harvested 24 DAF (lane 2), 36 DAF (lane 3), 48 DAF (lane 4), and 60 DAF (lane 5) were loaded. For 12 DAF (lane 1), 60 μg of protein was loaded.

The 36-DAF stage of seed development appeared to be a transitory stage, when both early (Ti-5, Ti-6, and Ti-7) and late (Ti-1, Ti-2, Ti-3, and Ti-4) stage-specific Ti were detected. Subsequent overlaying with repeated washing of the same gel on different radiographic films allowed detection of a faint Ti-5 band at 48 and 60 DAF. When more units (about 4-fold) of Ti activity were loaded on the gel, Ti-5 could be detected as a minor band at 48 and 60 DAF (results not shown). No proteinase activity was detected in extracts prepared from developing seeds (12 to 60 DAF) using either casein or benzoyl-arginyl-p-nitro-anilide as a substrate. The possibility of proteolysis of Pi during extraction or storage of extracts was minimized by extracting the seeds of all stages in the presence of specific chemical inhibitors of Ser, aspartic, metallo, and thiol proteinases. No significant differences were observed in the profiles of Ti activity in presence or absence of an exogenously added cocktail of inhibitors (data not shown).

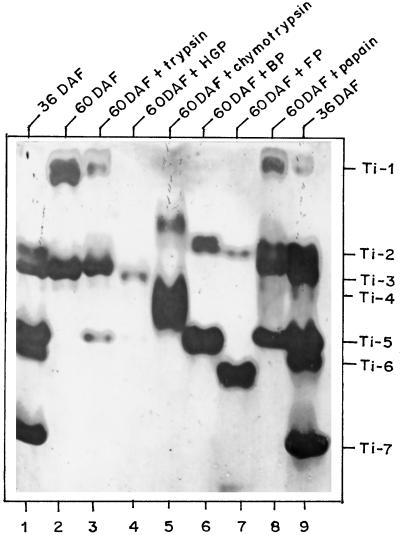

The occurrence of various stage-specific Ti during seed development prompted us to examine the relationships between these inhibitors. Treatment of 60-DAF seed extracts with different proteinases generated smaller fragments possessing Ti activity (Fig. 2). Prior to the treatment of the seed extracts, the optimal concentration of each proteinase was determined. This concentration resulted in the maximum number of Ti fragments without totally degrading Ti activity. Digestion with trypsin, bacterial proteinase, or papain appeared to convert Ti-1 to Ti-5 (Fig. 2, lanes 3, 6, and 8, respectively). Chymotrypsin treatment resulted in diffuse bands of Ti activity between Ti-1 and Ti-2 and between Ti-4 and Ti-5 (Fig. 2, lane 5), which may have been due to heterogeneous fragmentation of the inhibitor(s). The fungal proteinase produced two Ti-active bands and completely degraded Ti-1 and Ti-3 (Fig. 2, lane 7). Trypsin treatment of purified Ti-1 produced Ti-5 as a major active fragment but did not alter the mobility of Ti-3 or Ti-7. Ti-6 was completely digested by trypsin, and no band with Ti activity was produced (not shown).

Figure 2.

Limited proteolysis of chickpea Ti with exogenous proteinases. Seed extracts (60 DAF) were incubated with the appropriate proteinase at 37°C for 30 min and the mixture was loaded onto the gel. Ti bands were visualized as described in Methods. Lanes 1 and 9, Seed extract (36 DAF); lane 2, 60 DAF; lane 3, 60 DAF with trypsin (4 units); lane 4, 60 DAF with HGP (1 unit); lane 5, 60 DAF with chymotrypsin (2.5 units); lane 6, 60 DAF with bacterial proteinase (2 units); lane 7, 60 DAF with fungal proteinase (2 units); and lane 8, 60 DAF with papain (2 units).

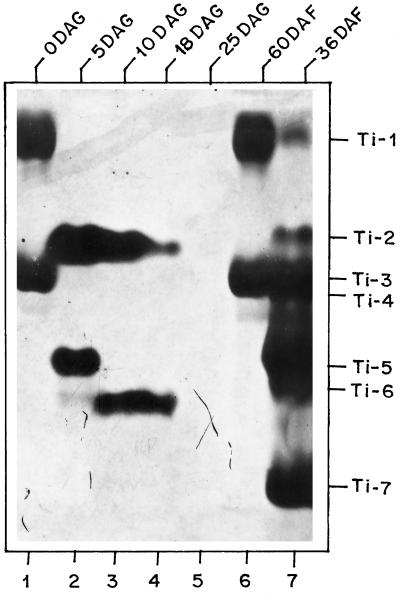

Ti during Seed Germination and Their Tissue Specificity

To determine if Ti were present during germination, seed extracts were analyzed 5, 10, 18, and 25 DAG. At 5 DAG, two bands of Ti activity were present (Fig. 3, lane 2). Between 5 and 18 DAG, the top band diminished and a new, lower band appeared in abundance (Fig. 3, lanes 2–4). The Ti bands present during germination had different mobilities than the Ti present in developing seeds at 36 DAF. At 25 DAG, no Ti activity bands were present (Fig. 3, lane 5).

Figure 3.

Electrophoretic profiles of chickpea Ti during germination. Ti profiles of extracts from germinating seed (15 μg of protein per lane) of 0, 5, 10, 18, and 25 DAG are shown. Ti bands were visualized as described in Methods. Lane 1, 0 DAG; lane 2, 5 DAG; lane 3, 10 DAG; lane 4, 18 DAG; lane 5, 25 DAG; lane 6, 60 DAF; and lane 7, 36 DAF.

Tisue specificity of Ti was determined by estimating Pi activity in the various tissues of 5-, 10-, 18-, 25-, and 70-d-old plants. No soluble Ti activity was detected in the extracts of shoots, leaves, flowers, or pod walls (data not shown). These extracts were also analyzed by the gel-activity assay. No inhibitor-activity band was detected, even though the method is sensitive for 2 ng of Ti proteins (Pichare and Kachole, 1994). These results demonstrate that chickpea Ti are seed specific and absent in other plant tissues.

Host-Pest Interaction

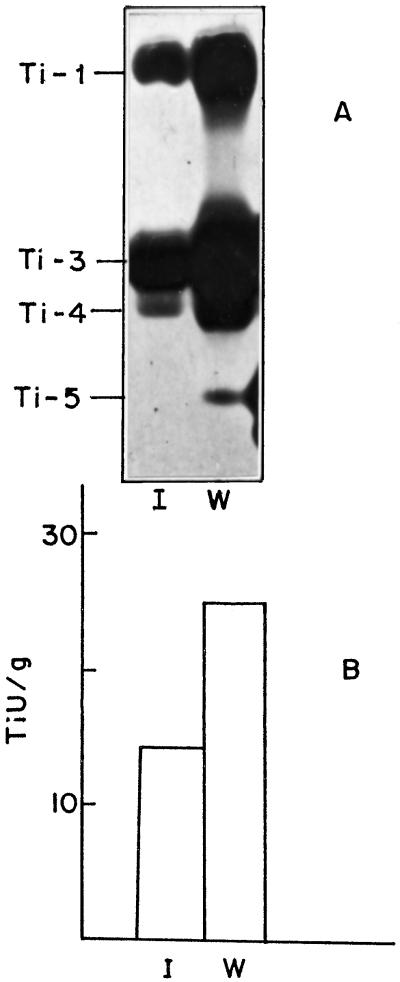

Wound Accumulation of Pi in Developing Seeds of Chickpea

Seeds from H. armigera-injured pods of 48 DAF (one of the stages of H. armigera attack) were collected, analyzed, and compared with uninjured seeds for Pi activity (Table II) and for electrophoretic profiles (Fig. 4). There was an increase in Ti, H. armigera gut Pi, and bacterial Pi activity in seeds of injured pods. Insect damage resulted in a 6-fold increase in H. armigera gut Pi activity and a 2-fold increase in Ti and bacterial Pi activity. Chymotrypsin inhibitor activity was not affected by insect damage (Table II). Electrophoretic analysis indicated that Ti-1, Ti-3, and Ti-4 dramatically increased in abundance. An additional band corresponding to Ti-5 appeared to be induced by insect injury (Fig. 4, lane W).

Table II.

Induction of Pi by H. armigera feeding

| Source | Inhibitor

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti | HGPi | BPi | Ci | |

| units g−1 seed meal | ||||

| Intact seeds | 14.52 | 0.17 | 0.50 | 1.43 |

| Wounded seeds | 24.91 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.47 |

| Fold increase | 1.71 | 5.88 | 2.04 | —a |

Seed extracts from 48 DAF seeds that were not exposed (intact seeds) or exposed to H. armigera larval feeding (wounded seeds) were tested for their ability to inhibit trypsin (Ti), H. armigera gut proteinases (HGPi), bacterial proteinase (BPi), or chymotrypsin (Ci), as described in Methods. Values are the averages of at least three replicates.

—, Negligible increase.

Figure 4.

Wound induction of chickpea Pi. Chickpea seeds (48 DAF) exposed to H. armigera feeding were analyzed for Ti bands (A) and Ti activity (B) as described in Methods. A, Ti profile of intact (lane I) and insect-damaged (lane W) seeds. Each lane contained 15 μg of seed protein. B, Ti activity of intact (I) and insect-damaged (W) seeds. TiU, Units of Ti activity.

In Vitro Proteolysis of Chickpea Ti by HGPs

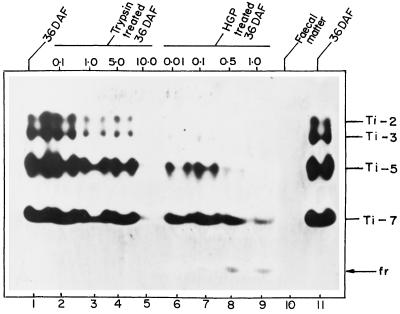

Seeds at the early stages of development are the most vulnerable to H. armigera attack. Since all Ti forms (Ti-1–Ti-7) were present at 36 DAF, this stage was used to study the interaction of Ti with insect proteinases. Incubation of 36-DAF seed extracts with HGP or trypsin resulted in similar Ti-fragment profiles (Fig. 5). This suggests that HGP has trypsin-like activity, as reported for other Heliothis-class insects (Broadway and Duffey, 1986; Purcell et al., 1992; Broadway, 1996). However, 10-fold less HGP than trypsin was required to degrade the Ti present in the 36-DAF seeds. HGP treatment also generated a small Ti fragment (labeled “fr” in Fig. 5, lanes 7–9), which accumulated with increasing HGP concentrations. Another important observation was that chickpea Ti-7 appeared to be most resistant of the Ti to proteolysis by trypsin or HGP (Fig. 5). This is of significance because Ti-7 is present during the stages of seed development when the H. armigera attack is maximum.

Figure 5.

Stability of chickpea Ti to proteolysis by HGP and trypsin. Effect of H. armigera midgut proteinases and trypsin on 36 DAF Ti was compared. Seed extracts were incubated with increasing concentrations of trypsin (0.1–10.0 units) and HGP (0.01–1.0 unit). Bands of Ti activity were visualized as described in Methods. Lanes 1 and 11, 36 DAF; lanes 2 to 5, extract treated with increasing concentrations of trypsin; lanes 6 to 9, extract treated with increasing concentrations of HGP; and lane 10, extract of fecal matter from larvae fed on developing chickpea seeds. fr, Active Ti fragment generated by HGP treatment.

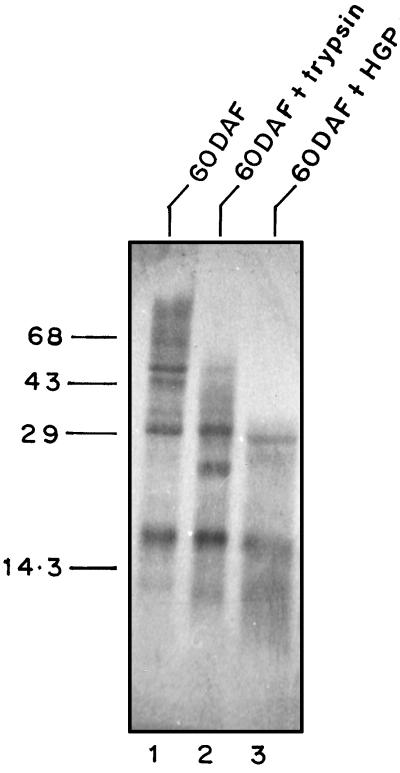

SDS-PAGE analysis of protein from mature seed treated with HGP and trypsin revealed that 4-fold less HGP than trypsin was sufficient to extensively digest the proteins (Fig. 6, lane 3). The trypsin-treated sample showed less degradation, suggesting that it was inhibited by the chickpea Ti (Fig. 6, lane 2). It is possible that the HGP more efficiently digested the chickpea proteins because it was able to inactivate the chickpea Ti.

Figure 6.

SDS-PAGE profiles of seed proteins (60 DAF) treated with HGP and trypsin. Total seed protein (100 μg) was treated with HGP (1 unit) or trypsin (4 units) for 30 min at 37°C. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Lane 1, 60 DAF; lane 2, 60 DAF with trypsin; and lane 3, 60 DAF with HGP.

In Vivo Digestion of Chickpea Ti by H. armigera Larvae

To understand the fate of chickpea Ti in the insect gut, H. armigera larvae were allowed to feed on 36- and 48-DAF pods, and the resulting fecal matter was analyzed for Ti activity by caseinolytic assay and on PAGE. No detectable Ti activity was observed in the assay and no band was seen by activity visualization (Fig. 5, lane 10) or by Coomassie brilliant blue staining (results not shown), indicating that there is a total digestion of the chickpea Ti in the insect gut.

DISCUSSION

Plant Pi have been extensively studied, and strategies for developing resistance against insect pests using Pi have been suggested (Garcia-Olmedo et al., 1987; Hilder et al., 1987; Ryan, 1990; Boulter, 1993; Jongsma et al., 1996; Michaud, 1997). A study of the synthesis and accumulation of Ti in developing chickpea seeds, which are extensively damaged by H. armigera feeding, was needed. Since no H. armigera-resistant chickpea genotypes are available, it was necessary to study Pi synthesis during seed development and the interaction of these inhibitors with insect gut proteinases. Such studies will help to devise strategies for obtaining sustainable practical solutions to insect-pest infestation in legumes.

Synthesis of Pi in chickpea begins at 24 DAF, and they steadily accumulate until seed maturation (60 DAF). Synthesis of storage proteins shows a lag phase until 36 DAF, followed by rapid accumulation thereafter (Table I). It is apparent that Pi are produced at early stages, prior to the accumulation of storage proteins. This process may have evolved to render young seeds unpalatable for feeding insects. High, inhibitor-specific activities were observed at this stage against most of the proteinases. The synthesis of storage proteins in the chickpea seeds occurs in the latter half of seed development, when the Pi are present for protection.

Multiple Isoinhibitors: Differential Expression or Posttranslational Modification?

Apart from high specific activities of chickpea Pi, there are qualitative differences in the Pi during seed development. Different electrophoretic forms of the Ti accumulate during seed development (Fig. 1). The differential appearance of Ti may be attributed to temporal expression of different genes or may be due to posttranslational modification of inhibitors or their pre-pro-proteins. The possibility of Ti degradation by endogenous proteinases was minimized by extracting the protein in presence of specific chemical Pi.

In vivo posttranslational modifications or proteolytic processing, if any, was simulated at least in part by treating the chickpea Ti-1 and Ti-3 with different proteinases. Limited proteolysis of chickpea seed Ti generated several active fragments, the major being Ti-5. The generation of active Ti species with proteinases does not necessarily suggest that the fragments are the same as those produced in vivo. No fragments corresponding to Ti-6 or Ti-7 were produced by any of the proteinases. This suggests that they are specifically expressed at the early stages of seed development. To confirm the differential expression of Ti species, northern analysis with specific Ti genes or the measurement of protein synthesis at different stages during seed development will be necessary. Based on the area and intensity of activity, it appeared that Ti-7 was synthesized at early stages of seed formation, decreased in abundance by 36 DAF, and disappeared thereafter. Ti-7 was more resistant to degradation by high concentrations of HGP than the other chickpea Ti. This may be significant because it is abundant at the stages of seed development that are most vulnerable to H. armigera attack.

Wound Induction of Pi by H. armigera Chewing of Developing Seeds of Chickpea

Although considerable information is available about wound-inducible Pi of tobacco and tomato (Green and Ryan, 1972; Ryan and An, 1988; Jongsma et al., 1994; Peña-Cortés et al., 1995; Schaller and Ryan, 1995; Conconi et al., 1996; Howe et al., 1996), little is known about the wound inducibility of Pi in seeds of leguminous plants. Since the inhibitors are synthesized as part of the plant's defense response, and developing seeds are the major target tissue, information about the induction and levels of Pi in seed in response to wounding at different stages of development would be valuable. Our results constitute the first report, to our knowledge, on the synthesis of chickpea Pi during seed formation and their increased accumulation in response to insect injury.

Although no specific, inducible Ti was observed, the amounts of Ti-1, Ti-3, Ti-4, and Ti-5 increased as a result of insect feeding on developing seeds (Fig. 4). We also determined that the seed protein reserves contain high levels of Pi, which accumulate before the bulk of seed proteins are synthesized. Finally, Ti-7, which is relatively stable in the presence of HGP, is produced at the early stages of development. Innovative use of stage-specific promoters and those involved in the chickpea defense mechanism with genes encoding heterologous Pi may provide an effective means to reduce preharvest losses of chickpea by H. armigera. Our data on the interaction between chickpea Ti and H. armigera gut proteinases provide the basis for a new biotechnological approach to strengthen chickpea's defense against the insect.

Chickpea Pi versus HGPs

In vivo studies to determine the fate of chickpea Pi in H. armigera guts clearly indicated that the larvae were able to degrade inhibitors efficiently. No traces of inhibitor activity or bands were detectable in the fecal matter of larvae fed on developing chickpea seeds (36 and 48 DAF). It has been recently demonstrated that insects secrete inhibitor-insensitive proteinases in response to feeding on transgenic tobacco plants expressing Pi genes or to feeding on potato leaves producing Pi in response to methyl jasmonate (Jongsma et al., 1995, 1996). The induction of Pi-resistant proteinases upon feeding insects on a diet containing Pi has also been demonstrated (Broadway, 1996). Our results provide evidence that H. armigera possesses inhibitor-insensitive proteinases that are able to degrade chickpea seed inhibitors. Michaud et al. (1995) reported proteolytic degradation of oryzacystatin II by proteinases of the coleopteran pest, black vine weevil (Otiorynchus sulcatus). This suggests that proteinase-mediated resistance to plant Pi appears to be the general strategy among herbivorous pests (Michaud, 1997).

It has been suggested that the insect proteinases might have undergone substitution of amino acids, which resulted in weakened interactions with plant Pi (Broadway, 1995, 1996; Jongsma et al., 1996). For example, Spodoptera exigua and Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) may adapt to plant Pi by producing inhibitor-insensitive proteinases (Bolter and Jongsma, 1995; Jongsma et al., 1995). However, the increased secretion of additional proteinases in response to the inhibitors requires the utilization of valuable amino acid pools that could starve the insects (Broadway and Duffey, 1986; Broadway, 1995). The physiological adaptation of insects to plant Pi therefore appears to be limited, and insects suffer considerably due to the presence of Pi in their natural host plants (Broadway and Duffey, 1986; Orozco-Cardenas et al., 1993; Bolter and Jongsma, 1995; Broadway, 1995, 1996; Jongsma et al., 1996).

Our present data suggest that a different mechanism may be used by H. armigera to counteract chickpea Ti. The H. armigera larvae produce about eight isoproteinases in their midguts (A.M. Harsulkar, A.P. Giri, V.S. Gupta, M.N. Sainani, V.V. Deshpande, and P.K. Ranjekar, unpublished results). Some of these isoproteinases might be insensitive to chickpea Pi and therefore are able to digest them (Figs. 2 and 5). The production of Pi-digesting proteinases allows the insect to overcome the plant defense and also use the digested inhibitors as a source of amino acids (Michaud, 1997). The Mexican bean weevil (Zabrotes subfasciatus) has developed a similar strategy to resist high levels of amylase inhibitors: it produces inhibitor-insensitive amylases and secretes a proteinase capable of digesting amylase inhibitors (Ishimoto and Chrispeels, 1996).

It would be of further interest to determine the specific site where the insect proteinases cleave the chickpea Pi. Amino acids near this site could be modified to make the Pi resistant to proteolysis by HGPs. Alternatively, a heterologous Pi could be expressed at early stages of chickpea seed development to inhibit the insect key proteinases and thereby improve the plant's defense mechanisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Professor Clarence A. Ryan, Charlotte V. Martin Professor, (Washington State University, Pullman) and Dr. Thomas J. Higgins (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, Canberra, Australia) for their critical review and valuable suggestions on the manuscript. The authors are also grateful to Dr. R.B. Deshmukh, Director of Research, Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth, Rahuri, India, and his colleagues for extending the necessary field facilities.

Abbreviations:

- DAF

days after flowering

- DAG

days after germination

- HGP

Helicoverpa armigera gut proteinase

- Pi

proteinase inhibitor(s)

- Ti

trypsin inhibitor(s)

Footnotes

This work was supported by a McKnight Foundation U.S.A. grant to National Chemical Laboratory, Pune, India, under the Collaborative Crop Research Program.

LITERATURE CITED

- Ambekar SS, Patil SC, Giri AP, Kachole MS. Proteinaceous inhibitors of trypsin and amylase in developing and germinating seeds of pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan L. Mill sp) J Sci Food Agric. 1996;72:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Belew M, Eaker D. The trypsin and chymotrypsin inhibitors in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.): identification of the trypsin reactive site, partial amino acid sequence and further physico-chemical properties of the major inhibitor. Eur J Biochem. 1976;62:499–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belew M, Porath J. Extracellular proteinase from Penicillium notatum. Methods Enzymol. 1970;19:576–581. [Google Scholar]

- Belew M, Porath J, Sundberg L. The trypsin and chymotrypsin inhibitors in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.): Purification and properties of the inhibitors. Eur J Biochem. 1975;60:247–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb20997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolter CJ, Jongsma MA. Colorado potato beetles (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) adapt to proteinase inhibitors induced in potato leaves by methyl jasmonate. J Insect Physiol. 1995;41:1071–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Botella MA, Xu Y, Prabha TN, Zhao Y, Narasimhan ML, Wilson KA, Nielsen SS, Bressan RA, Hasegawa PM. Differential expression of soybean cysteine proteinase inhibitors genes during development and in response to wounding and methyl jasmonate. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:1201–1210. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.3.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulter D. Insect pest control by copying nature using genetically engineered crops. Phytochemistry. 1993;34:1453–1466. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)90828-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadway RM. Are insects resistant to plant proteinase inhibitors? J Insect Physiol. 1995;41:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Broadway RM. Plant dietary proteinase inhibitors alter complement of midgut proteases. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 1996;32:39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Broadway RM, Duffey SS. Plant proteinase inhibitors: mechanism of action and effect on the growth and digestive physiology of larval Heliothis zea and Spodoptera exigua. J Insect Physiol. 1986;32:827–833. [Google Scholar]

- Carasco JF, Xavier-Filho J. Sequential expression of trypsin inhibitors in developing fruit of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata [L.] Walp) Ann Bot. 1981;47:259–266. [Google Scholar]

- Conconi A, Smerdon MJ, Howe GA, Ryan CA. The octadecanoid signalling pathway in plants mediates a response to ultraviolet radiation. Nature. 1996;383:826–829. doi: 10.1038/383826a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BJ. Disc electrophoresis II: methods and application to human serum. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1964;121:404–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1964.tb14213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan X, Li X, Xue Q, Abo-El-Saad M, Xu O, Wu R. Transgenic rice plants harboring an introduced potato proteinase inhibitor II gene are insect resistant. Nature Biotech. 1996;14:444–498. doi: 10.1038/nbt0496-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich PR, Raven PH. Butterflies and plants: a study in coevolution. Evolution. 1964;18:586–608. [Google Scholar]

- Erlanger BF, Kokowksy N, Cohen W. The preparation and properties of two new chromogenic substrates of trypsin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1961;95:271–281. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(61)90145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felton GW. Nutritive quality of plant protein: sources of variation and insect herbivore response. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 1996;32:107–130. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes KVS, Campos FAP, Val RRD, Xavier-Filho J. The expression of papain inhibitors during development of cowpea seeds. Plant Sci. 1991;74:179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (1993) FAO Production Yearbook, Vol 46. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy, pp, 105–115

- Garcia-Olmedo F, Salcedo G, Sanchez-Monge R, Gomez L, Roys J, Carbonero P. Plant proteinaceous inhibitors of proteases and amylases. Oxford Surv Plant Mol Cell Biol. 1987;4:275–334. [Google Scholar]

- Giri AP, Kachole MS (1997) Amylase inhibitors of pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan L.) seeds. Phytochemistry (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Green TR, Ryan CA. Wound-induced proteinase inhibitor in plant leaves: a possible defense mechanism against insects. Science. 1972;175:776–777. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4023.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harsulkar AM, Giri AP, Kothekar VS. Protease inhibitors of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) during seed development. J Sci Food Agric. 1997;74:509–512. [Google Scholar]

- Hilder VA, Gatehouse AMR, Sheerman SF, Barker RF, Boulter D. A novel mechanism of insect resistance engineered into tobacco. Nature. 1987;330:160–163. [Google Scholar]

- Howe GA, Lightner J, Browse, Ryan C. An octadecanoid pathway mutant (JL5) of tomato is compromised in signaling for defense against insect attack. Plant Cell. 1996;8:2067–2077. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.11.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimoto M, Chrispeels MJ. Protective mechanism of the Mexican bean weevil against high levels of α-amylase inhibitor in the common bean. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:393–401. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janzen DH. When is it coevolution? Evolution. 1980;34:611–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1980.tb04849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jibson MD, Birk Y, Bewley TA. Circular dichroism spectra of trypsin and chymotrypsin complexes with Bowman-Birk or chickpea trypsin inhibitor. Int J Peptide Protein Res. 1981;18:26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1981.tb02036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R, Narvaez J, An G, Ryan CA. Expression of proteinase inhibitors I and II in transgenic plants: effects on natural defense against Manduca sexta larvae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9871–9875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.9871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston KA, Lee MJ, Gatehouse JA, Anstee JH. The partial purification and characterization of serine protease activity in midgut of larval Helicoverpa armigera. Insect Biochem. 1991;21:389–397. [Google Scholar]

- Jongsma MA, Bakker PL, Peters J, Bosch D, Stiekema WJ. Adaptation of Spodoptera exigua larvae to plant proteinase inhibitors by induction of gut proteinase activity insensitive to inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8041–8045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.8041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongsma MA, Bakker PL, Visser B, Stiekema WJ. Trypsin inhibitor activity in mature tobacco and tomato plants is mainly induced locally in response to insect attack, wounding and virus infection. Planta. 1994;195:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jongsma MA, Stiekema WJ, Bosch D. Combating inhibitor-insensitive proteases of insect pests. Trends Biotech. 1996;14:331–333. [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus MT, White DWR, McGregor PG. Accumulation of a chymotrypsin inhibitor in transgenic tobacco can affect the growth of insect pests. Transgen Res. 1994;3:50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Michaud D. Avoiding protease-mediated resistance in herbivorous pests. Trends Biotech. 1997;15:4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Michaud D, Cantin L, Vrain TC. Carboxy-terminal truncation of oryzacystatin II by oryzacystatin-insensitive insect digestive proteinases. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;322:469–474. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud D, Nguyen-Quoc B, Vrain TC, Fong D, Yelle S. Response of digestive cysteine proteinases from the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) and the black vine weevil (Otiorynchus sulcatus) to a recombinant form of human stefin A. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 1996;31:451–464. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6327(1996)31:4<451::AID-ARCH7>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco-Cardenas M, McGurl B, Ryan CA. Expression of an antisense prosystemin gene in tomato plants reduces resistance towards Manduca sexta larvae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8273–8276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr GL, Strickland JA, Walsh TA. Inhibition of Diabrotica larval growth by a multicystatin from potato tubers. J Insect Physiol. 1994;40:893–900. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.2.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Cortés H, Fisahn J, Willmitzer Signals involved in wound-induced proteinase inhibitor II gene expression in tomato and potato plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4106–4113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichare MM, Kachole MS. Detection of electrophoretically separated protease inhibitors using x-ray film. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 1994;28:215–224. doi: 10.1016/0165-022x(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pueyo JJ, Hunt DC, Chrispeels MJ. Activation of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) α-amylase inhibitor requires proteolytic processing of the proprotein. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:1341–1348. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.4.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell JP, Greenplate JP, Douglas SR. Examination of midgut luminal proteinase activities in six economically important insects. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;22:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan CA. Protease inhibitors in plants: genes for improving defenses against insect and pathogens. Annu Rev Phytophathol. 1990;28:425–449. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan CA, An G. Molecular biology of wound-inducible proteinase inhibitors in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 1988;11:345–349. [Google Scholar]

- Saini HS, Weder JKP, Knights EJ. Inhibitor activities of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) against bovine, porcine and human trypsin and chymotrypsin. J Sci Food Agri. 1992;60:287–295. [Google Scholar]

- Sastry MCS, Murray DR. The contribution of trypsin inhibitors to the nutritional values of chickpea seed protein. J Sci Food Agric. 1987;40:253–261. [Google Scholar]

- Schaller A, Ryan CA. Systemin-a polypeptide defense signal in plants. BioEssays. 1995;18:27–33. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder HE, Gollasch S, Moore A, Tabe LM, Craig S, Hardie DC, Chrispeels MJ, Spencer D, Higgins TJV. Bean α-amylase inhibitor confers resistance to the pea weevil (Bruchus pisorum) in transgenic peas (Pium sativum L.) Plant Physiol. 1995;107:1233–1239. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.4.1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnoff P, Khalef S, Birk Y, Applebaum SW. A trypsin and chymotrypsin inhibitor from chickpeas (Cicer arietinum) Biochem J. 1976;157:745–751. doi: 10.1042/bj1570745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnoff P, Khalef S, Birk Y, Applebaum SW. Trypsin and chymotrypsin inhibitor from chickpeas-selective chemical modification of the inhibitor and isolation of two isoinhibitors. Int J Peptide Protein Res. 1979;14:186–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1979.tb01924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urwin PE, Atkinson HJ, Waller DA, McPherson MJ. Engineered oryzacystatin-I expressed in transgenic hairy roots confers resistance to Globodera pallida. Plant J. 1995;8:121–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.08010121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Xue Q, McElory D, Mawal Y, Hilder VA, Wu R. Constitutive expression of a cowpea trypsin inhibitor gene, CpTi, in transgenic rice plants confers resistance to two major rice insect pests. Mol Breed. 1996;2:167–173. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Botella MA, Subramanian L, Niu X, Nielsen SS, Bressan RA, Hasegawa PM. Two wound-inducible soybean cysteine proteinase inhibitors have greater insect digestive proteinase inhibitor activities than a constitutive homolog. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:1299–1306. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.4.1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]