Abstract

Legionnaires’ disease is caused by a lethal colonization of alveolar macrophages with the Gram-negative bacterium Legionella pneumophila. LpGT (L. pneumophila glucosyltransferase; also known as Lgt1) has recently been identified as a virulence factor, shutting down protein synthesis in the human cell by specific glucosylation of EF1A (elongation factor 1A), using an unknown mode of substrate recognition and a retaining mechanism for glycosyl transfer. We have determined the crystal structure of LpGT in complex with substrates, revealing a GT-A fold with two unusual protruding domains. Through structure-guided mutagenesis of LpGT, several residues essential for binding of the UDP-glucose-donor and EF1A-acceptor substrates were identified, which also affected L. pneumophila virulence as demonstrated by microinjection studies. Together, these results suggested that a positively charged EF1A loop binds to a negatively charged conserved groove on the LpGT structure, and that two asparagine residues are essential for catalysis. Furthermore, we showed that two further L. pneumophila glycosyltransferases possessed the conserved UDP-glucose-binding sites and EF1A-binding grooves, and are, like LpGT, translocated into the macrophage through the Icm/Dot (intracellular multiplication/defect in organelle trafficking) system.

Keywords: elongation factor 1A (EF1A), glucosyl transferase, Legionella pneumophila, microinjection, site-directed mutagenesis, protein structure

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade several studies have reported fascinating examples of pathogenic bacteria employing glycosyltransferases secreted into the human cell to control specific signal transduction pathways/cellular processes. For instance, the GT44 family {as annotated in the CAZY (carbohydrate-active enzyme) database; [1]} TcdA (Clostridium difficile toxin A) and TcdB (C. difficile toxin B) glycosyltransferase enzymes cause pseudomembranous colitis and antibiotic-associated diarrhoea by monoglucosylating Rho-family GTPases (such as Rho at Thr37, Rac at Thr35 and Cdc42) leading to the disruption of binding to GDIs (guanosine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors), inhibition of activation by GEFs (guanine-nucleotide-exchange factors), inhibition of the membrane–cytoplasm cycle and inhibition of the GTPase-active form [2-5]. Another bacterial glucosyltransferase, LpGT (Legionella pneumophila glucosyltransferase, also called Lgt1 or lpg1368) has been suggested to be involved in pathogenesis [6,7]. L. pneumophila is an intracellular opportunistic Gram-negative pathogen able to proliferate within human alveolar macrophages [8] and is the causative agent of Legionnaires’ disease [9]. This bacterium, once engulfed by macrophages, is able to replicate in vacuoles/phagosomes independently of the classical endolysosomal pathway [8,10], until nutrient levels decline, leading to activation of the Icm/Dot (intracellular multiplication/defect in organelle trafficking) type IV secretion system that releases several virulence factors [11]. At this stage, flagellated bacteria are released and infect new host cells. LpGT, annotated as a family GT88 glucosyltransferase in the CAZY database [1], was discovered to be a virulence factor, glucosylating Ser53 of hEF1A (human elongation factor 1A) by a retaining mechanism [12], leading to inhibition of ribosomal translation and consequently cell death [7]. However, the molecular mechanisms of glycosyl transfer and recognition of hEF1A are not understood.

In the present paper, we report the crystal structure of LpGT, which reveals a GT-A fold, demonstrating how the enzyme interacts with UDP-glucose. Through mutagenesis we identified residues important for catalysis and hEF1A recognition. We studied the effect of the residues on virulence, through microinjection studies, revealing that a positively charged hEF1A loop probably interacts with a conserved binding groove on LpGT. We also showed that two recently described apparent LpGT homologues, Lgt3 (L. pneumophila glucosyltransferase 3; also known as LegC5) and Lgt2 (L. pneumophila glucosyltransferase 2; also known as LegC8), possess a conserved UDP-glucose-binding site and hEF1A-binding groove and are, like LpGT, translocated through the Icm/Dot machinery, killing mammalian cells through induction of apoptosis.

EXPERIMENTAL

Cloning, mutagenesis and purification of L. pneumophila glucosyltransferases

Two open reading frames (lpg1368 and lpl1319; TrEMBL accessions Q5ZVS2 and Q5WWY0) encoding LppGT (LpGT from strain Philadelphia-1; ATCC 33152) and LplGT (LpGT from strain Lens) respectively were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA extracted from the respective strains using the primers listed in Supplementary Table S1 (available at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/426/bj4260281add.htm), and the PCR products were cloned directly into the bacterial expression vector pGEX6P1 (GE Healthcare).

Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out following the QuikChange® site-directed mutagenesis protocol (Stratagene), using the KOD HotStart DNA polymerase (Novagene). The resulting plasmid, pGEX6P1αlpgt Philadelphia strain, also referred to as wild-type, was used as template for introducing the following single amino-acid changes by site-directed mutagenesis: D246A, D248A, D246A-D248A, N293A, E445A, E446A, Y454A, N499A and S519A. FLAG tags were also incorporated by site-directed mutagenesis. All plasmids were verified by sequencing.

The plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) pLysS cells and grown at 37°C until reaching an attenuance of 0.6 at 600 nm, after which the expression of the protein was induced with 0.2 mM IPTG (isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside) at room temperature (23°C) for an overnight incubation. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3480 g for 30 min and resuspended in buffer A [25 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.5, 250 mM NaCl and 4 mM DTT (dithiothreitol)], containing lysozyme (1 mg/ml; Sigma–Aldrich), DNAse (0.1 mg/ml; Sigma–Aldrich) and protease inhibitors (1 tablet in 50 ml of lysis buffer; Roche). The cells were disrupted by a continuous-flow cell disruptor (Constant Systems) at a pressure of 30 psi (1 psi=6.9 kPa) and centrifuged at 19000 g at 4°C for 30 min. The supernatant was incubated at 4°C with glutathione–Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Biosciences), which had been equilibrated with buffer A for 2 h. Then the proteins were cleaved overnight at 4°C with PreScission (GE Healthcare) protease. The supernatant containing the proteins was concentrated prior to gel-filtration chromatograpy on a Superdex 75 XK26/60 column using an AKTA Prime system (GE Healthcare). The column was equilibrated with two column volumes of buffer B (25 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.5, 150 mM NaCl and 4 mM DTT). The purification was run at a flow rate of 1 ml/min and 3 ml fractions were collected. The eluted peak containing the protein was concentrated and used for crystallization trials, or frozen with 25% glycerol at −80°C.

Enzymology

Mammalian cell lysates were prepared from HEK (human embryonic kidney)-293 cells. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3480 g for 30 min and resuspended in cold lysis buffer C [50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 1 mM Na3VO4, 50 mM NaF, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 0.27 M sucrose and 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol] with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Protein concentrations of the lysates were determined using the Bradford method [13]. Glucosylation reactions were performed in 20 μl volumes consisting of buffer D (20 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM MnCl2), 7 μM recombinant glucosyltransferase, 50 μg of crude cell extract and 2.5 μM UDP-[3H]glucose (American Radiolabeled Chemicals). The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 3 h. The reaction was stopped by the addition of LDS (lithium dodecyl sulfate) sample buffer and heated at 100°C for 3 min. The samples were then subjected to SDS/PAGE (stacking and resolving gels at 4% and 12% respectively). Gels were stained with 0.1% Coomassie Brilliant Blue in 40% (v/v) methanol and 10% (v/v) acetic acid for 60 min and destained overnight with 10% (v/v) acetic acid and 30% (v/v) methanol. Incorporation of [3H]glucose in proteins was visualized by treatment with EN3HANCE (Perkin Elmer) for 30 min, followed by fluorography using X-Omat film (Kodak). Densitometry was quantified using Aida analysis software.

Binding of UDP-glucose to wild-type and mutant LppGT was analysed by ligand-induced quenching of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. Fluorescence measurements were carried out with a Varian Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer equipped with a thermostatted cuvette holder equilibrated at 25°C. Emission spectra were recorded from 300–400 nm upon excitation at 295 nm. Excitation and emission slits were opened to 10 nm and 20 nm respectively and the spectra were recorded at a scan speed of 9–60 nm/min. Standard reaction mixtures contained 1 μM of LpGT in 25 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM MnCl2 in a final volume of 1 ml. After pre-incubation for 10 min at 25°C within the cuvette holder, aliquots of UDP-glucose were added to the mixture (the total added volume did not exceed 2% of the total volume). The emission spectrum was recorded after each addition following mixing and 5 min incubation. All of the spectra were corrected for the background emission signal from both the buffer and the unbound UDP-glucose and repeated in triplicate. The equilibrium dissociation constant was obtained from fitting the fluorescence intensity data to the standard single-site binding equation with the software GraFit (Erithacus Software).

Microinjection

HeLa cells [14] were seeded on to 13-mm glass coverslips and allowed to settle overnight. The cells were then microinjected with 30 μM protein containing Texas Red-conjugated dextran (to localize the injected cells) in injection buffer E (100 mM glutamic acid, pH 7.2 with citric acid [15], 140 mM KOH, 1 mM MgSO4 and 1 mM DTT) as described previously [16]. The number of injection attempts were counted by the microinjector (Eppendorf) and recorded. Following incubation for 48 h, the cells were fixed in 4% (w/v) PFA (paraformaldehyde) in PBS and counterstained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) to distinguish apoptotic nuclei. The number of surviving cells (both those still adherent to the coverslip and rounded-up cells) were then counted and expressed as a percentage of the number of injection events. Note that not all injection events were successful and that after 48 h unperturbed cells would divide such that the final counts could exceed 100%.

Microscopy

HeLa cells were injected as described above with FLAG-tagged proteins and, following incubation for 24 h, the cells were fixed in 4% (w/v) PFA in PBS. The cells were then permeabilized with 1% NP-40 (Nonidet P40) in PBS and blocked with 0.5% fish-skin gelatin in PBS. The FLAG-tagged proteins were then localized with a mouse anti-FLAG antibody (M2, Sigma–Aldrich) and the ribosomes were localized with a rabbit anti-L26 protein antibody (Sigma–Aldrich). Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor®-488-conjugated goat anti-(mouse IgG) and Alexa Fluor®-594-conjugated goat anti-(rabbit IgG) (Molecular Probes) respectively. The cells were imaged on either a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope using an alpha Plan-Fluar 100× objective (numerical aperture 1.45) or a Leica sp2 confocal microscope using a HCX PL APO 63× objective (numerical aperture 1.40).

Crystallization and structure determination

LppGT was spin-concentrated to 26 mg/ml and chemically methylated following the protocol described by Walter et al. [17]. Crystals were grown by sitting-drop experiments at 20°C, mixing 1 μl of protein, containing 10 mM UDP-glucose and 2 mM MnCl2, with an equal volume of a reservoir solution {0.1 M Hepes, pH 7.5, 20% (w/v) PEG [poly(ethylene glycol)] 3000 and 0.2 M NaCl}. Under these conditions, crystals appeared within 7–14 days. They were cryoprotected with 0.1 M Hepes, pH 7.5, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 20% (w/v) PEG 3000 and 0.2 M NaCl, and flash-cooled prior to data collection at 100 K.

Following a similar protocol, LplGT was spin-concentrated to 18 mg/ml and co-crystallized with 10 mM UDP-glucose and 2 mM MnCl2. Crystals were grown in 0.1 M acetamido iminodiacetic acid, pH 6.5, 12% PEG 6000 and 0.1 M MgCl2. MPD (2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol) at 20% (v/v) in mother liquor was used as a cryoprotectant.

A mercury-chloride-derivative of LplGT was generated by soaking experiments in mother liquor, supplemented with 100 mM HgCl2, for 3–20 min prior to data collection. Data for the native crystals and the heavy-atom-derivative were collected at beamlines ID23-1/BM14 (European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France). All data were processed and scaled using the HKL suite [18] and CCP4 software [19]; relevant statistics are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Data collection and refinement statistics.

Values in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell. Ramachandran plot statistics were determined with PROCHECK [25].

| Parameter | LplGT HgCl2 derivative | LplGT and UDP-glucose | LppGT, UDP and glucose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | H 3 | H 3 | P 21 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.003 | 1.282 | 1.892 |

| Resolution (Å) | 20.0-2.10 | 20.0-1.9 | 20.0-2.1 |

| Cell dimensions |

a = 0122.3Å b = 0122.3Å c = 103.1Å |

a = 0122.8Å b = 0122.8 c = 103.4Å, |

a = 051.0Å b = 0104.6Å c = 53.3Å |

| Unique reflections | 33622 | 45918 | 31842 |

| Completeness | 0.999 (0.991) | 0.992 (0.969) | 0.971 (0.918) |

| Rsym | 0.099 (0.520) | 0.073 (0.50) | 0.125 (0.402) |

| I/σ(I) | 26.0 (5.7) | 29 (5.8) | 23.2 (5.5) |

| Redundancy | 12.8 (11.8) | 10.3 (7.2) | 6.5 (3.6) |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.199/0.261 | 0.189/0.254 | |

| RMSD from ideal geometry, bonds (Å) | 0.012 | 0.008 | |

| RMSD from ideal geometry, angles (°) | 1.4 | 1.2 | |

| B-factor (backbone bonds) RMSD (Å2) | 0.74 | 0.56 | |

| B-factor protein (Å2) | 35.4 | 27.3 | |

| B-factor UDP-glucose (Å2) | 29.4 | ||

| B-factor UDP (Å2) | 19.4 | ||

| B-factor glucose (Å2) | 26.9 | ||

| B-factor solvent (Å2) | 40.6 | 33.5 | |

| Ramachandran plot: | |||

| Most favoured (%) | 97.7 | 96.2 | |

| Additionally allowed (%) | 2.3 | 2.9 | |

| Generously allowed (%) | 0.0 | 0.21 | |

| PDB code | 2WZG | 2WZF |

By using SIRAS (single isomorphous replacement with anomalous scattering) methodology, with data from a crystal soaked with HgCl2, as well as a data set on a crystal of the LplGT co-crystallized with UDP-glucose (Table 1), macromolecular phasing with SHELX C/D/E (using the HKL2MAP graphical user interface [20]) identified six sites, yielding phases with a figure of merit of 0.72 to 2.1 Å (1 Å = 0.1 nm). An initial model for LplGT was built using ARP/wARP software [21] (building 370 residues of the single protein monomer in the asymmetric unit) and improved through cycles of manual model building in Coot [22] and refinement with REFMAC5 [23]. Molecular replacement with this structure was used to generate phases and a starting model for LppGT, which was refined using similar procedures. Topologies for UDP-glucose, UDP and glucose ligands were generated with PRODRG [24]. The final models were validated with PROCHECK [25] and WHATCHECK [26]; model statistics are given in Table 1.

Bacterial strains

The L. pneumophila strains used in this study were L. pneumophila JR32, a streptomycin-resistant, restriction-negative mutant of L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1, which is a wild-type strain in terms of intracellular growth [27], and GS3011, an icmT-deletion mutant [28].

Construction of CyaA (adenylate cyclase toxin) fusions

All genes examined were amplified by PCR using a pair of primers (Supplementary Table S1) containing suitable restriction sites at the 5′ end. The PCR products were subsequently digested with the relevant enzymes and cloned into the pMMB-cyaA–C or pMMB-cyaA–N vectors [29], to generate the plasmids listed in Supplementary Table S2 (available at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/426/bj4260281add.htm), all the inserts were sequenced to verify that no mutations were incorporated during the PCR.

Analyses performed with host cells

Intracellular growth assays in Acanthamoeba castellanii and in human promyelocytic leukaemia HL-60-derived macrophages were performed essentially as described previously [30]. The CyaA translocation assay was performed as described previously [31].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

LpGT adopts the GT-A fold with a flexible donor-binding loop

LppGT was cloned and expressed in E. coli as a GST (glutathione transferase) fusion protein and purified by affinity and gelfiltration chromatography. LppGT initially failed to produce diffraction quality crystals. Chemical methylation of solvent-exposed lysine residues led to a protein sample that produced a single, well-diffracting crystal (Table 1) for which the phase problem could not be solved. Our attention then shifted to the orthologous protein from L. pneumophila strain Lens, LplGT, which was cloned, expressed and purified using a similar strategy, readily producing well-diffracting crystals. The structure of LplGT bound to UDP-glucose was solved using a SIRAS experiment with a mercury derivative (Table 1 and Figure 1). The phase problem of the LppGT diffraction data (later found to include ordered UDP and glucose in the active site) was then solved by molecular replacement (Figure 1). Both structures were refined to high resolution, yielding final models with good R-factors (Table 1).

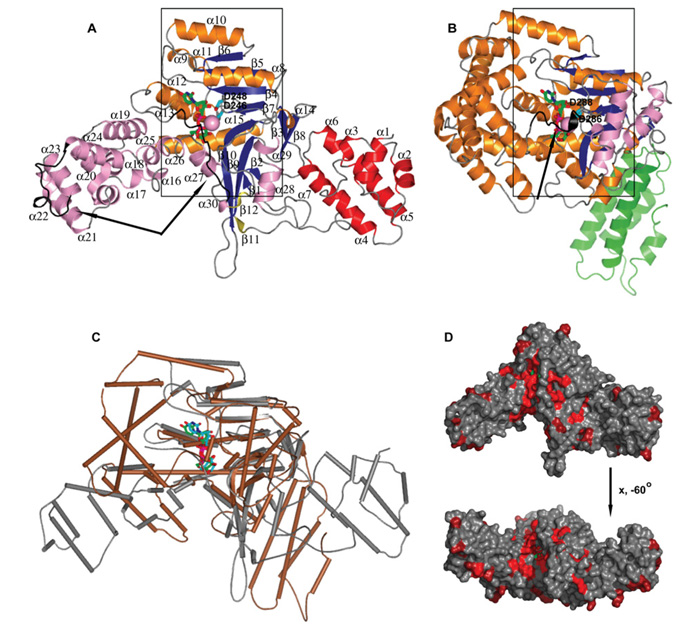

Figure 1. Structure of LpGT.

(A) Ribbon diagram of LppGT crystal structure in complex with UDP, glucose and manganese. (B) Comparison of LppGT crystal structure with TcdB (PDB codes 2BVL and 2BVM [34]). Secondary structures are represented in red and green for α-helixes of LppGT and toxin B N-terminal domain, brown and blue for α-helixes and β-strands in central domain of LppGT and toxin B, and pink and olive colour for α-helixes and β-strands of the C-terminal protrusion domain of LppGT and toxin B respectively. UDP and glucose are shown in green sticks and manganese as a pink sphere. The two aspartic acid residues (Asp246 and Asp248 in LppGT) are shown as cyan sticks. Arrows indicate flexible regions in both crystal structures. (C) Superposition of LppGT (grey) and TcdB (brown). UDP and glucose are shown in green and blue sticks in LppGT and TcdB respectively. (D) Surface representation of the LppGT enzyme, coloured by sequence conservation with Lgt2 and Lgt3 (from red, 100% identity, to grey, <50% identity).

The structures of LppGT/LplGT reveal three domains: a completely α-helical (α1–α7) N-terminal domain, a central domain, containing the double Rossmann fold-like signature typical of the GT-A fold (α8–α15/β1–β10) with a central β-sheet surrounded by α-helices on both sides, and a third domain, which we term the ‘protrusion domain’. The protrusion domain is an unusual α-helical protrusion from the GT-A fold, consisting mainly of α-helices (α16–α30) and two small β-strands (β11–β12). The well-defined density for Mg2+-UDP-glucose (LplGT) and Mn2+–UDP-glucose (LppGT), observed in the donor site, was almost completely formed by the central subdomain and a long C-terminal loop coming from the third domain (Figure 1A, see also Figure 4).

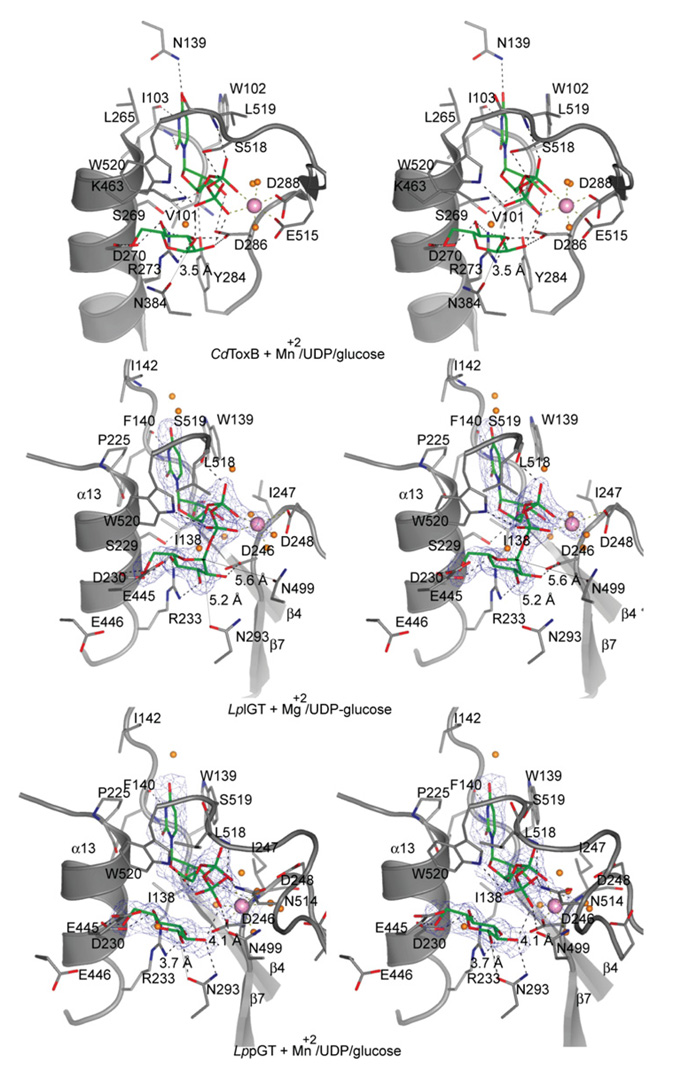

Figure 4. Active site of LpGT bound to UDP-glucose and metals.

Stereo images of the LplGT, LppGT and TcdB active sites. LplGT is shown in complex with UDP-glucose and Mg2+. LppGT and TcdB crystal structures are shown in complex with UDP, glucose and Mn2+. The amino acids are shown as grey sticks. The ligands and metals are shown as green sticks and pink spheres respectively. Protein–ligand hydrogen bonds are shown as broken black lines. The distances between Asn293 and Asn499 to the anomeric carbon are shown as thin lines. Unbiased (i.e. before inclusion of any inhibitor model) Fo–Fc, ϕcalc electron density maps are shown at 2.5 σ.

A comparison between the LppGT and LplGT structures revealed some conformational change within the N-terminal domains [RMSD (root mean square deviation) of 0.4 Å for 82 aligned Cα atoms] and differences in order/disorder of a number of regions, such as in a loop in the α-helical protrusion domain and in the C-terminal loop (residues 509–520; Figure 1A and see Supplementary Figure S1 available at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/426/bj4260281add.htm). Although these conformational changes could have resulted from differences in crystal packing (Table 1) or bound ligands (LplGT with Mg2+–UDP-glucose and LppGT with Mn2+–UDP-glucose), there have been many examples of metal- or donor-induced conformational changes of loops/regions in glycosyltransferases that contribute to formation of the acceptor-binding site [32]. In the LpGT structures, the flexible C-terminal loop was particularly well positioned to create the acceptor-binding site upon binding to the metal and UDP-glucose (Figure 1A).

LpGT is structurally homologous to C. difficile TcdB and two other Legionella glucosyltransferases

Surprisingly, analysis of the LpGT structures with the DALI server [33] revealed structural homology to C. difficile TcdB (PDB codes 2BVL and 2BVM [34]), Clostridium novyi α-toxin (PDB code 2VK9 [35]) and Clostridium sordellii lethal toxin (PDB codes 2VKD and 2VKH [35]). Whereas structure-based sequence alignments showed very low identities (14–18% with 185–199 aligned residues; Figure 2), the structural GT-A cores superimposed well (RMSDs of 2.5–3.2 Å, Figures 1A–1C). For example, TcdB is formed by the typical two abutting Rossmann-like folds, which creates the sugar-donor-binding site (Figure 1), and superimposed well with some secondary structures, such as β3–β10, α8, α11–α13 and α15 from LpGT (Figures 1B and 1C).

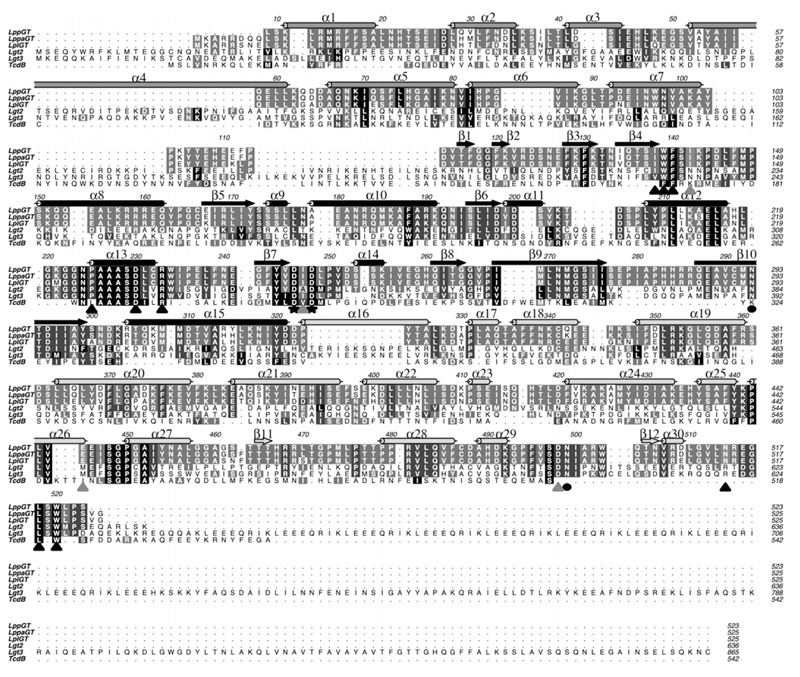

Figure 2. Multiple sequence alignment of the GT88 family members and TcdB.

GT88 members are LppGT, LppaGT (LpGT from strain Paris), LplGT, Lgt2 and Lgt3. Secondary structure elements from the LppGT structure are dark grey for the N-terminal domain, black for the central domain and light grey for the protrusion domain. Conserved catalytic glutamine residues are indicated with a black circle, the aspartic residues of the DxD motif are marked with a black star, amino acids interacting with UDP-glucose by direct hydrogen bonds or hydrophobic stacking interactions are highlighted with a black triangle, and amino acids interacting with UDP-glucose by indirect hydrogen bonds through water molecules are highlighted with a grey triangle.

A recent study has identified two further putative Legionella glucosyltransferases, Lgt2 (also known as LegC8) and Lgt3 (also known as LegC5), which are 72 kDa and 100 kDa proteins respectively, with additional multiple coiled-coil domains [36]. Although sequence alignments show a low level of overall sequence identity (18–28%; Figure 2), the crystal structures reveal several regions of high conservation, not only including the UDP-glucose-binding site and putative catalytic residues but also a putative acceptor-binding groove (Figure 1D). Furthermore, it was also shown that these three Legionella enzymes all possess glycosyl-transferase activity against hEF1A and kill eukaryotic cells [36].

Identification of the putative hEF1A-docking site

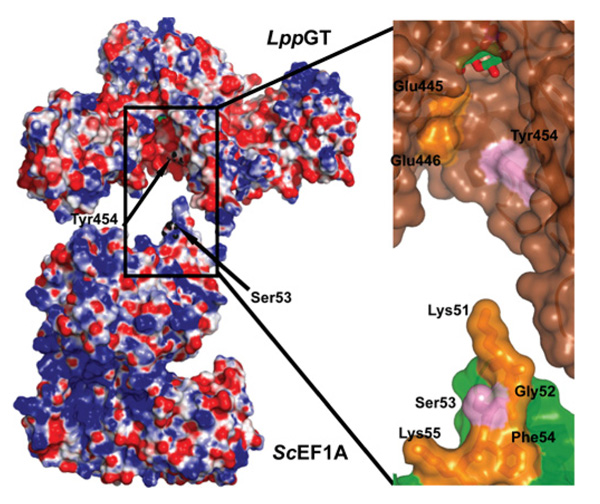

Structural analysis of the known hEF1A glucosylation site at Ser53, using the ScEF1A structure (Saccharomyces cerevisiae E1FA; PDB code 2B7B [37]), reveals this to be located at the tip of a loop between two helices extending approx. 20 Å from the surface of the protein. Ser53 is flanked by two lysine residues, which are conserved between hEF1A and ScEF1A, giving the tip of this loop on overall positive charge (Figure 3). Interestingly, electrostatic analysis of the conserved putative acceptor-binding site in LpGT reveals an overall negative charge (Figures 1D and 3), suggesting electrostatic complementarity between LpGT and the elongation factor glucosylation site. Using the constraints of the location of the UDP-glucose anomeric carbon, the Ser53 glucosylation site and the overall shape of the LpGT/ScEF1A proteins, it is possible to approximately position ScEF1A in the LpGT acceptor site, with qualitative shape-complementarity (Figure 3). To test this model of interaction, we targeted a key exposed aromatic residue, Tyr454, which lines the putative acceptor-binding site (Figure 3), by mutagenesis. Mutation of this residue to alanine led to a reduction in the activity towards hEF1A in HEK-293 lysates, whereas it did not significantly affect UDP-glucose binding (see Figure 5A and Table 2), suggesting an approximate identification of an EF1A-docking site on LpGT.

Figure 3. Electrostatic surface representation of LppGT and ScEF1A.

Left-hand panel: LppGT has a negatively charged binding groove, which may interact with the positively charged loop on ScEF1A (PDB code 2B7B [37]) that carries the acceptor serine. Tyr454, in the putative binding groove on LppGT, and the acceptor serine (Ser53) on ScEF1A are indicated by arrows. Right-hand panel: higher magnification representation of the putative interaction site between LppGT and ScEF1A. The surface of LppGT and ScEF1A are represented in brown and green respectively. Tyr454 and Ser53 are shown as sticks in pink; charged residues are in yellow (including some other residues forming the loop in which Ser53 is localized, such as Gly52 and Phe54).

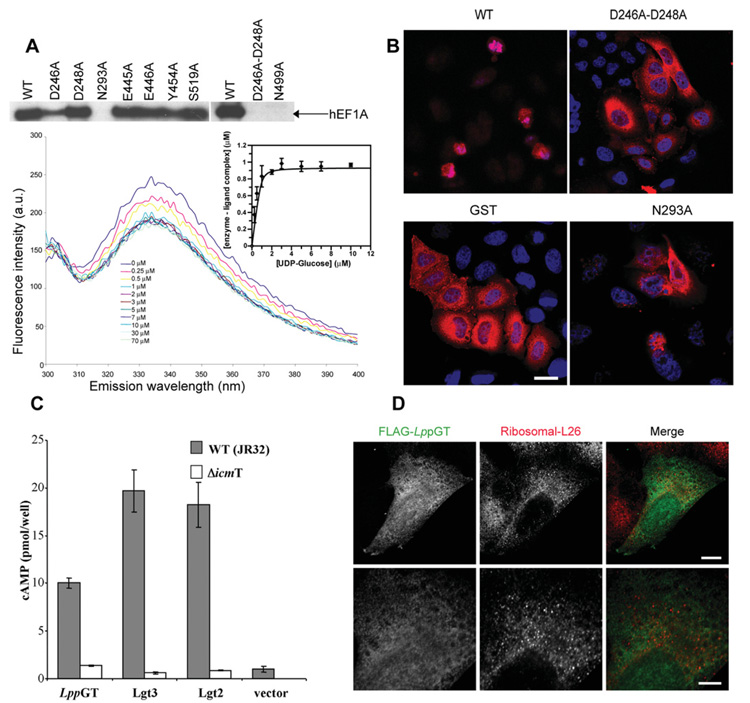

Figure 5. Site-directed mutagenesis, microinjection, translocation and localization studies.

(A) The upper panel shows autoradiography of wild-type and mutant enzymes incubated with HEK-293 lysates and UDP-[3H]glucose. The lower panel shows quenching of intrinsic LppGT tryptophan fluorescence measured at increasing concentrations of UDP-glucose. All data points represent the means ± S.D. for three measurements. The Kd for UDP-glucose was determined by fitting fluorescence intensity data against free UDP-glucose concentration (insert). See Table 2 for the Kd values for wild-type and mutant enzymes. (B) HeLa cells microinjected with wild-type LppGT, D246A/D248A double-mutant LppGT (D246A-D248A), LppGT-N293A and GST, as a control, at a protein concentration of 30 μM in the injection needle. Cells were co-injected with Texas Red-conjugated dextran and incubated for 48 h and are counterstained with DAPI. Representative images are shown for the cells after 48 h incubation. After injection of wild-type LppGT, there were few surviving red (Texas-Red–dextran-postive) cells and, of these, most had a rounded-up morphology when compared with cells injected with GST protein and the double mutant LppGT. LppGT-N293A was slightly protective compared with the wild-type enzyme. (C) Translocation experiments. All three enzymes were translocated through the Icm/Dot machinery (grey bars) compared with a mutated ΔicmT Legionella strain (white bars) as measured by cAMP concentrations. (D) Microinjected FLAG-tagged LppGT protein was injected into HeLa cells and incubated for 24 h. The FLAG-tagged protein (green) was diffusely distributed throughout the cell and showed rare co-localization with the counterstain against ribosomal L26 protein (red). The lower panels show a higher magnification of the image in the upper panels. Scale bar, 10 μm (upper panels) or 5 μm (lower panels). The proteins are FLAG-tagged at the C-terminus.

Table 2. Activity and UDP-glucose binding of single- and double-mutants of LppGT compared with wild-type enzyme.

The Kd for UDP-glucose was determined by fitting fluorescence intensity data, obtained by tryptophan fluorescence experiments, against free UDP-glucose concentration (Figure 3A). The activity and Kd experiments results represent means ± S.D. for three independent experiments. The percentage of surviving and intact HeLa cells was determined after 48 h; intact cells were not apoptotic and rounded and represent the mean of two independent experiments. nd, not detectable; –, not performed.

| LppGT varient | % activity | Kd (nM) | % surviving cells | % intact cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 100 | 100±29 | 33 | 10 |

| D246A | 48±3 | 400±80 | 38 | 18 |

| D248A | 92±3 | 990±90 | 36 | 18 |

| D246A/D248A double-mutant | nd | 830±100 | 100 | 95 |

| N293A | nd | 72±30 | 93 | 90 |

| E445A | 86±7 | 41±25 | – | – |

| E446A | 78±10 | 130±40 | – | – |

| Y454A | 43±2 | 60±30 | – | – |

| N499A | nd | 90±20 | 110 | 110 |

| S519A | 87±4 | 100±43 | – | – |

| GST | – | – | 305 | 300 |

| Buffer | – | – | 247 | 245 |

LppGT/LplGT binds UDP-glucose through loops from the central and protrusion domain

The two crystal structures described in the present paper reflect two different states during catalysis (Figure 4). The structure of LplGT was solved in complex with UDP-glucose and Mg2+, resembling the substrate-binding mode. The LppGT structure was solved in complex with UDP, glucose and Mn2+, resembling a product complex (Figure 4). In both structures, the nucleotides occupied the same positions and adopted the same conformations, with a shift in position observed for the glucose (maximum atomic shift of 1.6 Å). The nucleotide was located between three loops: α12–α13, α4–α8 and the C-terminal loop (which was disordered in the LplGT structure, where only residues 518–523 were visible; Figures 1A and 4). The uracil ring was sandwiched between Trp139 (β4–α8 loop) and Pro225 (located at the beginning of α13) by hydrophobic stacking interactions (Figure 4). With the exception of these two hydrophobic contacts, the majority of the interactions occurred through hydrogen bonds with backbone residues from Ile138, Trp139, Phe140, Ile142, Ile247 and Ser519 (Figure 4). Moreover, the phosphate group oxygen atoms were recognized by hydrogen bonds with the Ser519 and Trp520 side chains in the LplGT structure and, as a result of the shift in position of the glucose, Asn499, Asn514 and Trp520 side chains and the Leu518 backbone residue in the LppGT structure (Figure 2). Although Ser519 has a hydrogen bond with the UDP α-phosphate, mutation of this residue affected neither UDP-glucose binding nor activity (Figure 4 and Table 2). A structural comparison with TcdB showed that two conserved residues, Trp102 and Trp520 in TcdB (Figure 4), are involved in binding to uridine and phosphate groups, and are present in all GT44 Clostridium and GT88 Legionella enzymes, and they hence present a common sequence signature in these two large families of enzymes. Mutagenesis has shown that the Trp102 and Trp520 residues of TcdB are important for UDP-glucose binding and catalysis [38,39].

The DxD motif is essential for catalysis but not for donor binding

The active-site metals of GT-A-fold glycosyltransferases are known to have two roles: to induce a conformational change in a flexible loop and to stabilize a transition state during catalysis, with the help of two key aspartic acids in an Asp-Xaa-Asp or DxD motif [32,40,41]. The phosphate group oxygen atoms, Asp248 of the DxD motif and two ordered water molecules appear to pentagonally co-ordinate the metal (Mg2+) in the LplGT structure, whereas the LppGT reveals a hexagonally co-ordinated Mn2+, using an additional water molecule and with Asp246 instead of Asp248 (Figure 4); this is accompanied by a shift of 1.8 Å in the position of the metal. The importance of the DxD motif in LpGT has been investigated previously using the D246N single or D246N/D248N double mutants, which result in a decrease in glucosyltransfer activity against hEF1A [7]. We investigated the role of these residues further to dissect the effects on donor binding and activity. The D248A mutant showed no significant reduction of overall activity, but binding of UDP-glucose was an order of magnitude weaker as measured by tryptophan fluorescence (Figure 5A and Table 2), in agreement with the donor-binding role of the aspartic acid residues in the DxD motif, as proposed previously [42,43]. However, the D246A mutant showed a significant reduction in activity compared with the LppGT wild-type enzyme, with only a moderate reduction in donor binding (Figure 5A and Table 2). Strikingly, the D246A/D248A double mutant had no detectable activity and reduced binding of UDP-glucose by an order of magnitude (Figure 5A and Table 2). Thus the aspartic acid residues in the DxD motif may have roles in stabilization of the transition state and activity, as proposed previously by Qasba et al. [32], in addition to being important, although not essential, for binding of UDP-glucose [42-44].

In the substrate complex, glucose is hydrogen-bonded to Asp230, Arg233 and Asp246, whereas in the product-binding mode structure Asn293 has this role instead of Asp246. These changes in hydrogen bonding and the position of the DxD motif may reflect the shift in ligand position and the identity of the metal (Figure 4). Interestingly, two of the glucose-interacting residues (Asp230 and Arg233) are conserved in TcdB (Asp270 and Arg273 respectively; Figure 4). Mutation of these residues in TcdB had significant effects on binding to UDP-glucose and activity [39].

The LpGT active site structure confirms a retaining mechanism with two catalytic asparagine residues

TcdB belongs to a large family of GT-A glycosyltransferases with retaining character [45]. Among this family, the better characterized enzymes include the Neisseria meningitidis galactosyltransferase, LgtC [42,46-48], the bovine α-1,3-galactosyltransferase, 3GalT [49], the two enzymes responsible for the formation of blood type A and B, GTA (α-1,3-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase) and GTB (α-1,3-galactosyltransferase) [50-52] respectively, ppGalNAcTs (polypeptide N-α-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases) [53-55] and MGS (mannosylglycerate synthase) [56]. For these retaining enzymes, a glutamine or glutamic acid residue has been proposed as the catalytic nucleophile involved in a DN*ANss ion-pair mechanism [45]. Comparison of LpGT, TcdB and other retaining glycosyltransferase active sites suggests that LpGT may follow a retaining mechanism (Figure 4), in agreement with recent work that has established a retaining mechanism for this enzyme by NMR spectroscopy [12]. The structures reveal not only conservation of the DxD motif and glucose-binding residues, but also a key asparagine residue (Asn293), positioned approx. 4 Å away from the anomeric carbon, in a similar manner to Gln189 in LgtC and Asn384 in TcdB, which are proposed to be involved in a back-side nucleophilic push [42,45]. We mutated all LpGT residues close to the anomeric carbon, including Asn293 and Asn499, as well as Glu445 and Glu446, two residues positioned such that they could possibly act as a catalytic base if LpGT employed an inverting mechanism (Figure 4). As expected, none of these residues affected binding of UDP-glucose (Table 2), a result which also confirmed that these mutant proteins were properly folded. Furthermore, mutation of the two glutamate residues did not affect activity of LpGT towards hE1FA in cell lysates (Figure 5A). Strikingly, however, mutation of either Asn293 or Asn499 resulted in mutant enzymes without any detectable glucosyltransfer activity (Figure 5A). Thus these mutations confirm that LpGT follows a retaining catalytic mechanism as proposed for C. difficile toxin and other glycosyltransferases [42,45-48]. Given the position of the two asparagine residues, Asn293 could act as the weak nucleophile involved in pushing the anomeric carbon during the Sni (substitution nucleophilic internal)-like mechanism (through a DN*ANss ion-pair) and Asn499 may play an essential role in stabilizing the transition state and the leaving group.

Inactive LpGT mutants are impaired in induction of HeLa cell apoptosis

Although it is known that the toxicity of LpGT stems from its glucosylation of hEF1A, the precise mechanism of cell death is as yet unclear. Immunofluorescence microscopy analysis of HeLa cells microinjected with wild-type LppGT suggested that the cells die with typical hallmarks of apoptosis, such as clumped DNA in the nuclei, plasma membrane blebbing and dead cells in phagosomes of adjoining cells (Figure 5B and Supplementary Figure S2 available at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/426/bj4260281add.htm). More studies will be required to address how these enzymes, in addition to disruption of ribosome translation, induce apoptosis in mammalian cells.

We repeated the microinjection experiments using the LppGT mutants generated as part of the present study. Although all the mutants and wild-type LppGT showed some detectable levels of cell death within 48 h, as reported previously [7], all the mutants, with the exception of the D246A and D248A single mutants (from the DxD motif), showed a significant reduction in cell death compared with the wild type (Figure 5B and Table 2). The fact that the catalytically inactive mutants protected against cell death but not growth suggests that the toxicity of LppGT does not entirely depend on its glucosyltransferase activity. It is possible that the inactive mutants are still able to disrupt protein–protein complexes or deplete hEF1A levels.

LppGT, Lgt2 and Lgt3 are exported through the Icm/Dot machinery

Although LppGT, Lgt2 and Lgt3 have been shown to kill mammalian cells in electroporation experiments [7,36], and we also see cell death in microinjection studies (as described above), it is as yet unclear how these enzymes are exported from Legionella into the macrophages. It is worth noting that a range of known Legionella virulence factors are substrates for the Icm/Dot system used by the bacterium to secrete virulence factors into the macrophage cytosol [10,57,58]. We tested whether LppGT, LegC5 and LegC8 were substrates for the Icm/Dot system by N-terminally fusing these enzymes to inactive CyaA, and stably expressing the proteins in L. pneumophila strain JR32. These stable transfectants were used to infect HL-60-derived macrophages, and cAMP levels were determined to follow translocation [30]. In agreement with a previous study [59,60], Lgt3 was translocated into the macrophage and similar results were obtained for Lgt2 (Figure 5C). Surprisingly, however, no significant cAMP levels were detected for LppGT (results not shown for an N-terminal fusion of LppGT with CyaA). The majority of the L. pneumophila Icm/Dot substrates are known to contain a C-terminal signal sequence [61]. Interestingly, the only crystal structure of a type IV effector, RalF [62], shows a C-terminal disordered region within the last 20 residues as the signal sequence [62,63], and secondary structure predictions suggest the Lgt3 and Lgt2 C-termini contain a similar number of disordered amino acids. However, the LppGT structure shows that the C-terminus is well-ordered and, indeed, forms part of the active site (Figure 1A). Thus we decided to repeat the secretion experiment with a C-terminal fusion of LppGT with CyaA. Strikingly, this led to translocation into macrophages (Figure 5C), suggesting that, unusually, LpGT contains its type IV signal sequence at the N-terminus (Figures 1A and 5C). The N-terminus of LppGT is α-helical with only the first ten residues being completely disordered. It is not clear whether these residues are necessary and sufficient as a type IV secretion signal or whether a structural motif may be required for recognition by the Icm/Dot machinery. With the exception of LpGT, only two other previous studies report cases of effector proteins carrying N-terminal type IV signal peptides [60,64]. Taken together, these results are consistent with a model whereby LppGT, Lgt2 and Lgt3 are virulence factors; they are ejected by L. pneumophila into the macrophage and contribute to cell death through inhibition of protein synthesis.

Considering the differences in sequence and length between LpGT, Lgt2 and Lgt3, it is possible that these enzymes show differences in localization in mammalian cells. To study this, we expressed C-terminally FLAG-tagged versions of these enzymes (which retain full activity; results not shown) in E. coli and microinjected these into HeLa cells. Despite the significant differences in sequence and length (Figure 2), all three were diffusely distributed throughout the cell, showing some co-localization with the ribosomal L26 protein, in agreement with hE1FA being one of the substrates of these enzymes (localization of LppGT shown in Figure 5D; results not shown for Lgt2 and Lgt3).

Conclusions

Legionella is an accidental intracellular infectious bacterium. During the life cycle in the host macrophage, the bacterium needs to tightly control host cell processes to allow optimal replication without (initially) killing the host. At the end of the replication stage, apoptosis is induced and bacteria are released. Numerous effectors have been described, and some cases of redundancy have been reported [58,65,66]. In the present study we have investigated a family of redundant glucosyltransferases, which kill mammalian host macrophages by apoptosis through post-translational modification of hEF1A and other, as yet unknown, mechanisms which are independent of their catalytic activity (as suggested by our microinjection studies with inactive mutants). Our data suggest redundancy in localization and activity and reveals the LpGT, Lgt2 and Lgt3 are all Icm/Dot effectors, consistent with the notion that they are virulence factors.

It is not clear why L. pneumophila would inject these three proteins with similar activities and localization patterns into the host cell. Studies carried out by Belyi et al. [36] show that LpGT and Lgt2 are produced at the beginning of the stationary phase of its growth curve, whereas Lgt3 is only produced at the early stage of the growth curve. Thus it is possible that Legionella only makes these proteins in the slowly replicating and non-dividing stages, either at the beginning or at the end of host infection. There are many other examples of Legionella secreting redundant virulence factors; DrrA and SidM [58], which are a GEF and GDF (GDI displacement factor) respectively, LidA [65], which binds to Rab1-GTP and LepB [66], which is a GAP (GTPase-activating protein), are all involved in the human Rab1 cycle. Similarly, LppGT, Lgt2 and Lgt3 may form a redundant mammalian killer toxin family, which may be relevant to start new infections and produce host death by apoptosis in order to infect new cells. In order to address how important these enzymes are in the Legionella infection cycle, studies with single, double and triple knockouts should be performed.

Our structural studies show that LpGT is a metal-dependent enzyme, which possesses a GT-A fold. This structure supports the notion that Lgt2 and Lgt3 are also active glycosyltransferases, possessing conserved UDP-glucose and acceptor-binding sites. Structural and mutation analyses suggest that a negatively charged binding groove in LpGT may recognize a positively charged loop in EF1A which carries the acceptor serine residue. Mutagenesis studies on several amino acids in the active site suggest that LpGT may employ a retaining mechanism involving two catalytic residues: Asn293 acting as the weak nucleophile, and Asn499 stabilizing the transition state and the UDP leaving-group. It appears that the DxD motif is important for catalysis, yet not essential for donor binding.

In conclusion, LpGT, Lgt2 and Lgt3 are a redundant set of virulence factors forming a glucosyltransferase family with a conserved putative EF1A-binding site and acting via a retaining mechanism. The present study will form the basis for future studies towards the protein substrate specificity of these enzymes and the development of chemical biological probes for further cell biological studies of these virulence factors.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France, for beamtime.

FUNDING

This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship and a Medical Research Council Programme grant (to Daan van Aalten).

Abbreviations used

- CyaA

adenylate cyclase toxin

- CAZY

carbohydrate-active enzyme

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EF1A

elongation factor 1A

- GEF

guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- GST

glutathione transferase

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- Icm/Dot

intracellular multiplication/defect in organelle trafficking

- Lgt2

L. pneumophila glucosyltransferase 2

- Lgt3

L. pneumophila glucosyltransferase 3

- LgtC

N. meningitidis galactosyltransferase

- LpGT

L. pneumophila glucosyltransferase

- LplGT

LpGT from strain Lens

- LppGT

LpGT from strain Philadelphia-1

- PEG

poly(ethylene glycol)

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- RMSD

root mean square deviation

- SIRAS

single isomorphous replacement with anomalous scattering

- TcdB

C. difficile toxin B

Footnotes

The structural co-ordinates reported will appear in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 2WZF and 2WZG.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Ramon Hurtado-Guerrero and Daan van Aalten initiated the project. Ramon Hurtado-Guerrero, Shalini Pathak, Alan Prescott and Gil Segal designed the type of experiments to be performed. Ramon Hurtado-Guerrero, Tal Zusman, Shalini Pathak, Adel Ibrahim, Sharon Shepherd and Alan Prescott performed the experiments. Ramon Hurtado-Guerrero, Alan Prescott, Gil Segal and Daan van Aalten interpreted the results. Ramon Hurtado-Guerrero and Daan van Aalten wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coutinho PM, Henrissat B. Carbohydrate-active enzymes: an integrated database approach. In: Gilbert HJ, Davies G, Henrissat B, Svensson B, editors. Recent Advances in Carbohydrate Bioengineering. The Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge: 1999. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Just I, Selzer J, Wilm M, von Eichel-Streiber C, Mann M, Aktories K. Glucosylation of Rho proteins by Clostridium difficile toxin B. Nature. 1995;375:500–503. doi: 10.1038/375500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schirmer J, Aktories K. Large clostridial cytotoxins: cellular biology of Rho/Ras-glucosylating toxins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1673:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyerly D, Wilkins TD. Clostridium difficile. Raven Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jank T, Giesemann T, Aktories K. Rho-glucosylating Clostridium difficile toxins A and B: new insights into structure and function. Glycobiology. 2007;17:15R–22R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belyi I, Popoff MR, Cianciotto NP. Purification and characterization of a UDP-glucosyltransferase produced by Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:181–186. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.181-186.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belyi Y, Niggeweg R, Opitz B, Vogelsgesang M, Hippenstiel S, Wilm M, Aktories K. Legionella pneumophila glucosyltransferase inhibits host elongation factor 1A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:16953–16958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601562103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albert-Weissenberger C, Cazalet C, Buchrieser C. Legionella pneumophila: a human pathogen that co-evolved with fresh water protozoa. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007;64:432–448. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6391-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumpers P, Tiede A, Kirschner P, Girke J, Ganser A, Peest D. Legionnaires’ disease in immunocompromised patients: a case report of Legionella longbeachae pneumonia and review of the literature. J. Med. Microbiol. 2008;57:384–387. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47556-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ninio S, Roy CR. Effector proteins translocated by Legionella pneumophila: strength in numbers. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:372–380. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shin S, Roy CR. Host cell processes that influence the intracellular survival of Legionella pneumophila. Cell. Microbiol. 2008;10:1209–1220. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belyi Y, Stahl M, Sovkova I, Kaden P, Luy B, Aktories K. Region of elongation factor 1A1 involved in substrate recognition by Legionella pneumophila glucosyltransferase Lgt1: identification of Lgt1 as a retaining glucosyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:20167–20174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.008441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumann B, Held M, Liebel U, Erfle H, Rogers P, Pepperkok R, Ellenberg J. High-throughput RNAi screening by time-lapse imaging of live human cells. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:385–390. doi: 10.1038/nmeth876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Izant JG, Weatherbee JA, McIntosh JR. A microtubule-associated protein antigen unique to mitotic spindle microtubules in PtK1 cells. J. Cell. Biol. 1983;96:424–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.2.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prescott AR, Dowrick PG, Warn RM. Stable and slow-turning-over microtubules characterize the processes of motile epithelial cells treated with scatter factor. J. Cell Sci. 1992;102:103–112. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walter TS, Meier C, Assenberg R, Au KF, Ren J, Verma A, Nettleship JE, Owens RJ, Stuart DI, Grimes JM. Lysine methylation as a routine rescue strategy for protein crystallization. Structure. 2006;14:1617–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collaborative Computational Project The CCP4 Suite: Programs for Protein Crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pape D, Seil R, Kohn D, Schneider G. Imaging of early stages of osteonecrosis of the knee. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 2004;35:293–303. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perrakis A, Morris R, Lamzin VS. Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:458–463. doi: 10.1038/8263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schuttelkopf AW, van Aalten DM. PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:1355–1363. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904011679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laskowski RA, Moss DS, Thornton JM. Main-chain bond lengths and bond angles in protein structures. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;231:1049–1067. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hooft RW, Vriend G, Sander C, Abola EE. Errors in protein structures. Nature. 1996;381:272. doi: 10.1038/381272a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadosky AB, Wiater LA, Shuman HA. Identification of Legionella pneumophila genes required for growth within and killing of human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 1993;61:5361–5373. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5361-5373.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zusman T, Yerushalmi G, Segal G. Functional similarities between the icm/dot pathogenesis systems of Coxiella burnetii and Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:3714–3723. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3714-3723.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zusman T, Aloni G, Halperin E, Kotzer H, Degtyar E, Feldman M, Segal G. The response regulator PmrA is a major regulator of the icm/dot type IV secretion system in Legionella pneumophila and Coxiella burnetii. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;63:1508–1523. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Segal G, Shuman HA. Legionella pneumophila utilizes the same genes to multiply within Acanthamoeba castellanii and human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:2117–2124. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2117-2124.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altman E, Segal G. The response regulator CpxR directly regulates expression of several Legionella pneumophila icm/dot components as well as new translocated substrates. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:1985–1996. doi: 10.1128/JB.01493-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qasba PK, Ramakrishnan B, Boeggeman E. Substrate-induced conformational changes in glycosyltransferases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holm L, Sander C. Dali: a network tool for protein structure comparison. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995;20:478–480. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reinert DJ, Jank T, Aktories K, Schulz GE. Structural basis for the function of Clostridium difficile toxin B. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;351:973–981. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ziegler MO, Jank T, Aktories K, Schulz GE. Conformational changes and reaction of clostridial glycosylating toxins. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;377:1346–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belyi Y, Tabakova I, Stahl M, Aktories K. Lgt: a family of cytotoxic glucosyltransferases produced by Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:3026–3035. doi: 10.1128/JB.01798-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersen GR, Pedersen L, Valente L, Chatterjee I, Kinzy TG, Kjeldgaard M, Nyborg J. Structural basis for nucleotide exchange and competition with tRNA in the yeast elongation factor complex eEF1A:eEF1Balpha. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1261–1266. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Busch C, Hofmann F, Gerhard R, Aktories K. Involvement of a conserved tryptophan residue in the UDP-glucose binding of large clostridial cytotoxin glycosyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:13228–13234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jank T, Giesemann T, Aktories K. Clostridium difficile glucosyltransferase toxin B: essential amino acids for substrate binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:35222–35231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramakrishnan B, Qasba PK. Crystal structure of lactose synthase reveals a large conformational change in its catalytic component, the β-1,4-galactosyltransferase-I. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;310:205–218. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Charnock SJ, Davies GJ. Structure of the nucleotide-diphospho-sugar transferase, SpsA from Bacillus subtilis, in native and nucleotide-complexed forms. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6380–6385. doi: 10.1021/bi990270y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Persson K, Ly HD, Dieckelmann M, Wakarchuk WW, Withers SG, Strynadka NC. Crystal structure of the retaining galactosyltransferase LgtC from Neisseria meningitidis in complex with donor and acceptor sugar analogs. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:166–175. doi: 10.1038/84168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Busch C, Hofmann F, Selzer J, Munro S, Jeckel D, Aktories K. A common motif of eukaryotic glycosyltransferases is essential for the enzyme activity of large clostridial cytotoxins. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:19566–19572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y, Malinovskii VA, Fiedler TJ, Brew K. Role of a conserved acidic cluster in bovine β-1,4 galactosyltransferase-1 probed by mutagenesis of a bacterially expressed recombinant enzyme. Glycobiology. 1999;9:815–822. doi: 10.1093/glycob/9.8.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lairson LL, Henrissat B, Davies GJ, Withers SG. Glycosyltransferases: structures, functions, and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.061005.092322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lairson LL, Chiu CP, Ly HD, He S, Wakarchuk WW, Strynadka NC, Withers SG. Intermediate trapping on a mutant retaining α-galactosyltransferase identifies an unexpected aspartate residue. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:28339–28344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y, Swaminathan GJ, Deshpande A, Boix E, Natesh R, Xie Z, Acharya KR, Brew K. Roles of individual enzyme–substrate interactions by α-1,3-galactosyltransferase in catalysis and specificity. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13512–13521. doi: 10.1021/bi035430r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jamaluddin H, Tumbale P, Withers SG, Acharya KR, Brew K. Conformational changes induced by binding UDP-2F-galactose to α-1,3 galactosyltransferase: implications for catalysis. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;369:1270–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gastinel LN, Bignon C, Misra AK, Hindsgaul O, Shaper JH, Joziasse DH. Bovine α-1,3-galactosyltransferase catalytic domain structure and its relationship with ABO histo-blood group and glycosphingolipid glycosyltransferases. EMBO J. 2001;20:638–649. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamamoto F, Clausen H, White T, Marken J, Hakomori S. Molecular genetic basis of the histo-blood group ABO system. Nature. 1990;345:229–233. doi: 10.1038/345229a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patenaude SI, Seto NO, Borisova SN, Szpacenko A, Marcus SL, Palcic MM, Evans SV. The structural basis for specificity in human ABO(H) blood group biosynthesis. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:685–690. doi: 10.1038/nsb832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee HJ, Barry CH, Borisova SN, Seto NO, Zheng RB, Blancher A, Evans SV, Palcic MM. Structural basis for the inactivity of human blood group O2 glycosyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:525–529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fritz TA, Hurley JH, Trinh LB, Shiloach J, Tabak LA. The beginnings of mucin biosynthesis: the crystal structure of UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide α-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-T1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:15307–15312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405657101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kubota T, Shiba T, Sugioka S, Furukawa S, Sawaki H, Kato R, Wakatsuki S, Narimatsu H. Structural basis of carbohydrate transfer activity by human UDP-GalNAc: polypeptide α-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (pp-GalNAc-T10) J. Mol. Biol. 2006;359:708–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fritz TA, Raman J, Tabak LA. Dynamic association between the catalytic and lectin domains of human UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide α-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:8613–8619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Flint J, Taylor E, Yang M, Bolam DN, Tailford LE, Martinez-Fleites C, Dodson EJ, Davis BG, Gilbert HJ, Davies GJ. Structural dissection and high-throughput screening of mannosylglycerate synthase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:608–614. doi: 10.1038/nsmb950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shohdy N, Efe JA, Emr SD, Shuman HA. Pathogen effector protein screening in yeast identifies Legionella factors that interfere with membrane trafficking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:4866–4871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501315102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murata T, Delprato A, Ingmundson A, Toomre DK, Lambright DG, Roy CR. The Legionella pneumophila effector protein DrrA is a Rab1 guanine nucleotide-exchange factor. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:971–977. doi: 10.1038/ncb1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Buck E, Anne J, Lammertyn E. The role of protein secretion systems in the virulence of the intracellular pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Microbiology. 2007;153:3948–3953. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/012039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Felipe KS, Pampou S, Jovanovic OS, Pericone CD, Ye SF, Kalachikov S, Shuman HA. Evidence for acquisition of Legionella type IV secretion substrates via interdomain horizontal gene transfer. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:7716–7726. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.22.7716-7726.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cambronne ED, Roy CR. The Legionella pneumophila IcmSW complex interacts with multiple Dot/Icm effectors to facilitate type IV translocation. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e188. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nagai H, Cambronne ED, Kagan JC, Amor JC, Kahn RA, Roy CR. A C-terminal translocation signal required for Dot/Icm-dependent delivery of the Legionella RalF protein to host cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:826–831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406239101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagai H, Kagan JC, Zhu X, Kahn RA, Roy CR. A bacterial guanine nucleotide exchange factor activates ARF on Legionella phagosomes. Science. 2002;295:679–682. doi: 10.1126/science.1067025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen J, Reyes M, Clarke M, Shuman HA. Host cell-dependent secretion and translocation of the LepA and LepB effectors of Legionella pneumophila. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:1660–1671. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Machner MP, Isberg RR. Targeting of host Rab GTPase function by the intravacuolar pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Dev. Cell. 2006;11:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ingmundson A, Delprato A, Lambright DG, Roy CR. Legionella pneumophila proteins that regulate Rab1 membrane cycling. Nature. 2007;450:365–369. doi: 10.1038/nature06336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.