Abstract

This investigation examines the protonation of diiron dithiolates, exploiting the new family of exceptionally electron-rich complexes Fe2(xdt)(CO)2(PMe3)4, where xdt is edt (ethanedithiolate, 1), pdt (propanedithiolate, 2), and adt (2)aza-1,3-propanedithiolate, 3), prepared by the photochemical substitution of the corresponding hexacarbonyls. Compounds 1-3 oxidize near −950 mV vs Fc+/0. Crystallographic analyses confirm that 1 and 2 adopt C2-symmetric structures (Fe-Fe = 2.616, 2.625 Å, respectively). Low temperature protonation of 1 afforded exclusively [μ-H1]+, establishing the nonintermediacy of the terminal hydride ([t-H1]+). At higher temperatures, protonation afforded mainly [t-H1]+. The temperature dependence of the ratio [t-H1]+/[μ-H1]+ indicates that the barriers for the two protonation pathways differ by ~4 kcal/mol. Low temperature 31P{1H} NMR measurements indicate that the protonation of 2 proceeds by an intermediate, proposed to be the S-protonated dithiolate [Fe2(Hpdt)(CO)2(PMe3)4]+ ([S-H2]+). This intermediate converts to [t)H2]+ and [μ)H2]+ by a first order process (t1/2 ~ 2.5 h, 20 °C). Protonation of the 3 affords exclusively terminal hydrides, regardless of the acid or conditions to give [t-H3]+, which isomerizes to [t-H3′]+ wherein all PMe3 ligands are basal. DFT calculations support transient protonation at sulfur and the proposal that the S-protonated species (e.g., [S-H2]+) rearranges to the terminal hydride intramolecularly via a low energy pathway.

Introduction

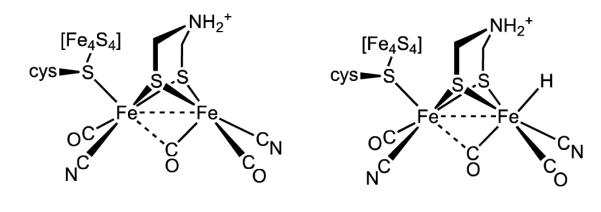

The protonation of diiron dithiolates is a central step in the production of dihydrogen catalyzed by the [FeFe]-hydrogenases.1,2 Crystallographic characterization of the protein and subsequent spectroscopic and computational experiments of the active site point to an apical site on the distal Fe center for the binding site for hydrogenic substrates. Being adjacent to the binding site of the hydride/dihydrogen substrate, the ammonium/amine cofactor is proposed to relay protons to and from the redox-active diiron active site.3,4 In this way, the cofactor compensates for the slow rates that are typical for protonation of metal centers.5

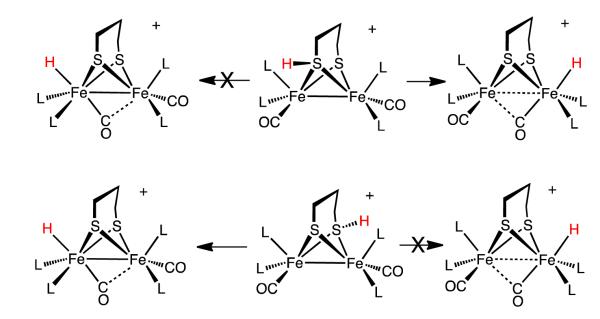

At least in the Hox state of the enzyme, the distal Fe center adopts the “rotated geometry”, wherein the three diatomic ligands are rotated by ca. 60° relative to the conventional pseudo-C2v structure. This rotation exposes a vacant coordination site at the apical position approximately trans to the semi-bridging CO ligand (Figure 1).4,6 For reduced diiron complexes, the rotated structure has only been observed in nitrosylsubstituted diiron thiolates.7 Electron-rich (i.e., basic) diiron derivatives with rotated structures have not been prepared, despite the synthesis of hundreds of compounds of the type Fe2(SR)2(CO)6-nLn (L = CN, PR3, SR2, CNR).8-10 In view of the rarity of electron-rich, rotated diiron dithiolates, it is reasonable to suggest that the “vacant site” in fact is occupied by a hydride ligand in the Hred state. This proposal, if verified, would refocus modeling efforts to diferrous compounds with terminal hydrides (Figure 1). There is consensus that such terminal hydrides occur, if not as Hred itself, then as transient intermediates during the production and oxidation of H2.

Figure 1.

Structure of the active site of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase in the Hox state (left). The structure of the Hred state remains uncertain - both structures are consistent with available observations. The amine cofactor is shown in the protonated form, although its protonation state is not known.

Despite their centrality to biological function, diiron compounds with terminal hydride ligands are rarely examined. Instead, the modeling literature is dominated by studies on isomeric bridging hydrido complexes.9 No biophysical evidence indicates any role for these μ-hydrides, although some complexes are catalytically active.2,9 The first structurally characterized terminal hydride of a diiron dithiolate was [HFe2(edt)(CO)2(PMe3)4]PF611, which in fact was prepared using hydride reagents, not by protonation. The other major family of isolable terminal hydrides are [HFe2(xdt)(CO)2(dppv)2]+, which arise from protonation of the very bulky Fe2(xdt)(CO)2(dppv)2 (dppv = 1,2-cis-C2H2(PPh2)2).12,13 We recently described the crystallographic characterization of the ammonium dication [HFe2(adtH)(CO)2(dppv)2]2+.14

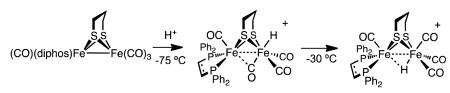

Interest in terminal hydrides expanded with the 2007 report that they are intermediates in the protonation of Fe2(pdt)(CO)4(dppe) (dppe = 1,2-C2H4(PPh2)2). When this complex was protonated with HBF4·Et2O at −75 °C, a transient hydride was observed, indicated by a characteristic 1H NMR signal near δ −4. This signal is assigned to the terminal hydride arising from protonation of the Fe(CO)3 center (eq 1).15

|

(1) |

Protonation of Fe2(pdt)(CO)4(dppe) at −50 °C produces a second terminal hydride, resulting from protonation at the Fe(dppe)(CO) site. Both isomeric hydrides convert to the μ-hydride above −30 °C. Similar results have been observed by us12,13 and Hogarth.16,17 The Ezzaher report raised the possibility that many or all other diiron(I) dithiolates protonate to give terminal hydrides as kinetic intermediates. Puzzling is the non-observation of terminal hydrides upon low-temperature protonation of the symmetrically disubstituted compound Fe2(pdt)(CO)4(PMe3)2, although the tetrasubstituted derivative Fe2(pdt)(CO)2(dppv)2 does give a terminal hydride.12,13 Even in cases where terminal hydrides have not been detected,18,19 questions have lingered about their existence as metastable intermediates en route to terminal hydride complexes.20 Compelling evidence that protonation of diiron dithiolates can proceed without the intermediacy of a terminal hydride is provided in this report.

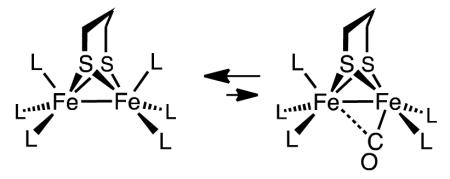

Another unsolved puzzle for the formation of terminal hydrides arising from the protonation of Fe2(SR)2(CO)6-xLx is the absence of a vacant terminal site to receive the proton. Theoretical calculations indicate that rotated structures are destabilized by ca. 10 kcal/mol relative to the pseudo-C2v isomer (eq 2).8,21,22

|

(2) |

In this report, we provide an explanation for the occurrence of terminal hydrides from diiron compounds that do not adopt rotated structures. We complete the report with a study of the derivative containing the actual azadithiolate cofactor, HN(CH2S−)2.3,12 The regiochemistry of its protonation differs completely from the edt and pdt derivatives, consistent with its biological function.

Results and Discussion

Preparation and Protonation of Fe2(edt)(CO)2(PMe3)4

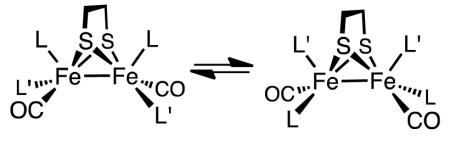

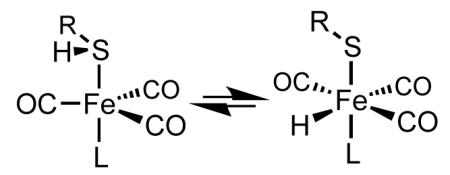

The conversion of Fe2(edt)(CO)6 into the tetrasubstituted complex Fe2(edt)(CO)2(PMe3)4 (1) was conducted photochemically in neat PMe3 as the reaction solvent. The product exhibits νCO bands at 1856 and 1835 cm−1, lower than any previously reported diiron(I) compounds (Table I).23 At 5 °C, the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of 1 shows two signals, consistent with the bis(apical-basal) stereochemistry with idealized C2 symmetry. The room temperature 1H NMR spectrum showed only one signal in the PMe3 region, which splits at lower temperatures in accord with the stereodynamic process shown in eq 3.24

|

(3) |

Table 1.

IR Spectral Data for New and Related Complexes.

| Compound | ν CO | solvent |

|---|---|---|

| Fe2(edt)(CO)4(PMe3)2 | 1982(s), 1944(s), 1908(s), 1896(m, br) |

MeCN25 |

| Fe2(edt)(CO)2(PMe3)4 (1) | 1856 (m), 1835 (s) | CH2Cl2 |

| Fe2(pdt)(CO)4(PMe3)2 | 1979(m), 1942(s), 1898(s) | MeCN25 |

| Fe2(pdt)(CO)2(PMe3)4 (2) | 1857 (m), 1836 (s) | CH2Cl2 |

| Fe2(adt)(CO)2(PMe3)4 (3) | 1860 (m), 1839 (s) | CH2Cl2 |

| Fe2(pdt)(CO)2(dppv)2 | 1888, 186823 | CH2Cl2 |

| [t-HFe2(edt)(CO)2(PMe3)4]+ ([t-H1]+) |

1940 (m), 1874 (s) | MeCN11 |

| [t-HFe2(pdt)(CO)2(PMe3)4]+ ([t-H2]+) |

1944 (m), 1883 (s) | CH2Cl2 |

| [t-HFe2(adt)(CO)2(PMe3)4]+ ([t-H3]+) |

1945 (m), 1879 (s) | CH2Cl2 |

| [t-HFe2(pdt)(CO)2(dppv)2]+ | 1965, 190513 | CH2Cl2 |

| Hred (C. Reinhardtii) | 1935, 1881, 1793 | H2O26 |

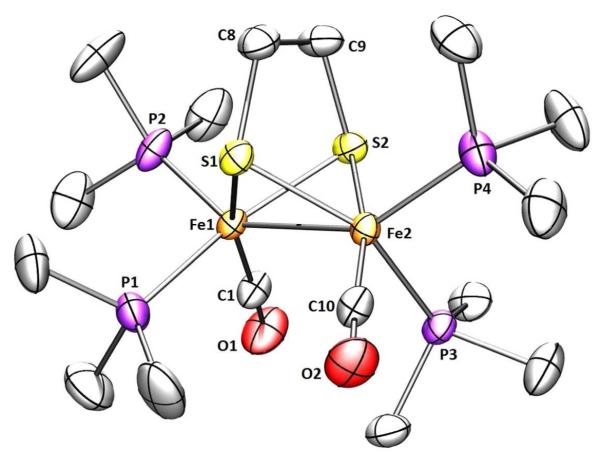

Crystallographic analysis confirmed that 1 has idealized C2 symmetry (Figure 2). The Fe(1)-Fe(2) distance is about 0.1 Å longer compared to Fe2(edt)(CO)4(PMe3)2.25 Perhaps reflecting the electron-rich character of the diiron center, the Fe-CO distances are 1.734(3) and 1.723(3) Å, about 0.04 Å shorter compared to the disubstituted analog.25 The dihedral angle S(1)-Fe(1)-Fe(2)-S(2) is 103.11° and the dihedral angle P(1)-Fe(1)-Fe(2)-P(3) is 94.24° leaving the iron-iron bond relatively more accessible than in the corresponding pdt compound discussed below.

Figure 2.

Structure of 1 showing 50% thermal ellipsoids. Selected distances (Å) and angles (deg): Fe1-Fe2, 2.6164(6); Fe-Pavg, 2.204; S(1)-Fe(1)-Fe(2)-S(2), 103.1; P(1)-Fe(1)-Fe(2)-P(3), 94.24.

The protonation of 1 by H(OEt2)2BArF4 in CD2Cl2 solution was monitored by NMR spectroscopy. Already at −90 °C, upon thawing the mixture of acid and complex, the solution color rapidly changed from deep green to red. The first and exclusive product was the bridging hydride [(μ-H)Fe2(edt)(CO)2(PMe3)4]+ ([μ-H1]+),11 as verified by 31P{1H} and 1H NMR spectra. As discussed more fully in the Conclusions, we note that under the conditions of the experiment, the isomeric terminal hydride [t-H1]+ is quite stable,11 so this protonation experiment establishes that the terminal hydride is not an intermediate in the formation of the μ-hydride.

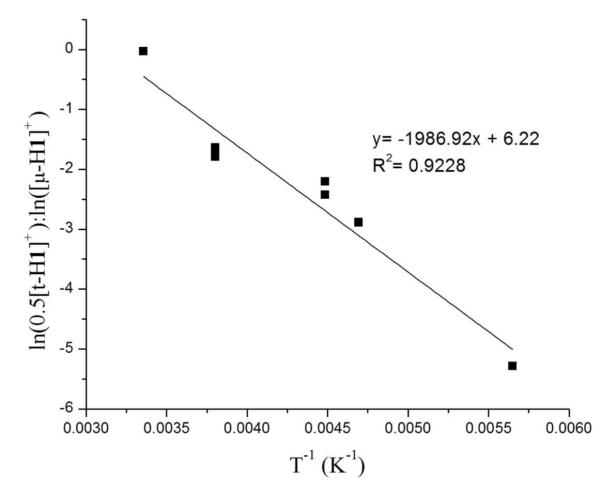

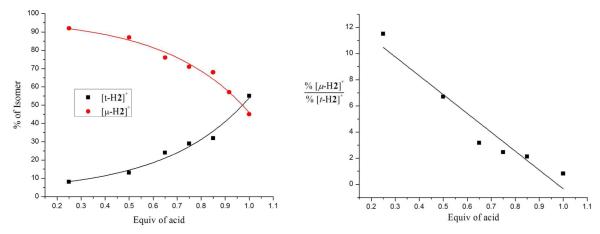

Surprisingly, the regiochemistry of protonation of 1 varied strongly with temperature. In contrast to the low temperature results (100% [μ-H1]+) room temperature protonation produced mainly [t-H1]+ (66%), with the remainder being [μ-H1]+. The difference is visually obvious - the terminal hydride is bright green and the bridging hydride is red.11 At intermediate temperatures the product ratio varied between the two extremes. Since the rate of isomerization of [t-H1]+ into [μ-H1]+ is relatively slow, we could obtain reliable ratios of the kinetic products by integration of 1H NMR spectra. The 66-33 ratio for [t-H1]+:[μ-H1]+ reflects the kinetic product distribution in the case that two equivalent sites exist for terminal protonation. The ratio ln(0.5[t-H1]+):ln([μ-H1]+) varies linearly with 1/T, the slope, ΔΔG*/R, indicating that the barriers for the protonations leading to [t-H1]+ and [μ-H1]+ differ by 4 kcal/mol (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Temperature dependence of the product ratio [t-H1]+/[μ-H1]+ resulting from the protonation of CD2Cl2 solutions of 1 with H(OEt2)2BArF4 at various temperatures.

Preparation and Protonation of Fe2(pdt)(CO)2(PMe3)4

Using the methods for the preparation of 1, we also synthesized Fe2(pdt)(CO)2(PMe3)4 (2). The IR and NMR spectroscopic properties of 2 and 1 are very similar. At −90 °C the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum exhibits broadening of one of the two signals (supporting information), attributed to the slowing of conformational equilibrium of the pdt bridge, which is proposed to more strongly affect the chemical shifts of the apical PMe3 ligands.21 In the parent complex Fe2(pdt)(CO)6, coalescence is observed at about −60 °C,21 indicating that the PMe3 groups lower this barrier.

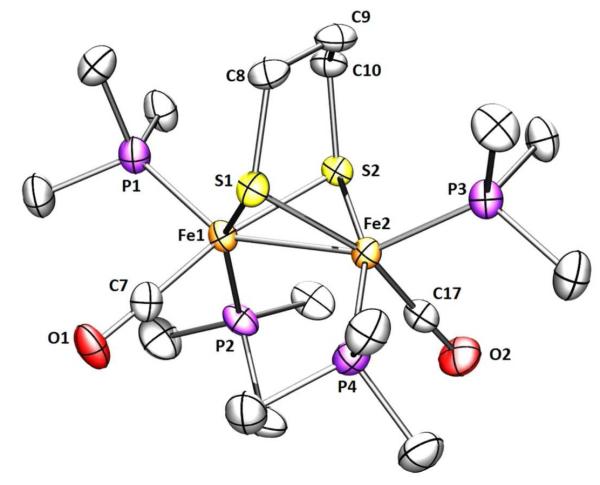

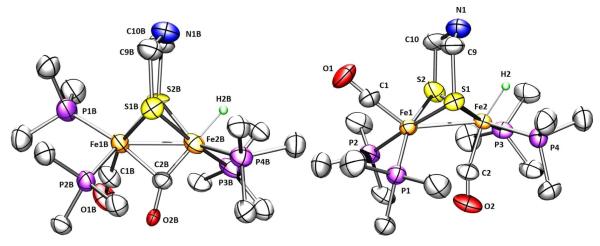

Crystallographic analysis of 2 revealed two symmetrically independent molecules in the asymmetric unit together with three molecules of pentane. Compound 2 adopts the expected pseudo-C2 symmetry with a bis(apical-basal) disposition of the phosphine ligands (Figure 4). Reflecting its impact of the bulky PMe3 groups, the Fe(1)-Fe(2) distance is 2.625(7) Å, significantly longer than 2.555(2) Å for Fe2(pdt)(CO)4(PMe3)2.25 The dihedral angle S(1)-Fe(1)-Fe(2)-S(2) is 109.69°, about 6.6° wider than in 1. The dihedral angle P(2)-Fe(1)-Fe(2)-P(4) is 90.05°, about 4.2° smaller than the edt derivative confirming that, compared to 1, the Fe-Fe bond is more shielded by the phosphine ligands.

Figure 4.

Structure of 2 showing 50% thermal ellipsoids. Selected distances (Å) and angle (deg): Fe1-Fe2, 2.6252(7); Fe-Pavg, 2.212; S(1)-Fe(1)-Fe(2)-S(2), 109.69; P(2)-Fe(1)-Fe(2)-P(4), 90.05.

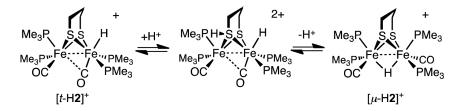

Protonation of 2 with one equiv of H(OEt2)2BArF4 at −80 °C gave a 2:1 ratio of the bridging and terminal hydrides, [μ-H2]+ and [t-H2]+. Together with the 31P{1H} NMR data, the observation of a triplet of triplets in 1H NMR spectrum at δ −18.8 (JPH = 27.2, 3.4 Hz) is consistent with a symmetrical bridging hydride. The structure of [t-H2]+ is also indicated by the NMR data. The chemical shift (δ −2.2) indicates a terminal hydride.15 The 50 Hz difference in 2JPH is striking, but similarly disparate values are observed for [t-H1]+ (JPH = 50, 96 Hz).11 The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum is also consistent with the presence of as single unsymmetrical diastereoisomer. The ratio [μ-H2]+/[t-H2]+ does not change upon warming the sample to ambient temperatures. At 20 °C, [t-H2]+ isomerize to [μ-H2]+ with a half-life of about 2.5 h (k = 8·10−5 s−1) in CD2Cl2 solution. No further isomerization is observed when a CD2Cl2 solution of [μ-H2]BArF4 is heated for 3 days at 60 °C in a flame-sealed tube.

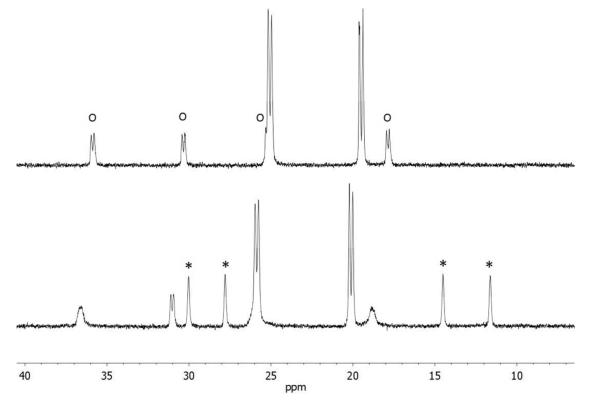

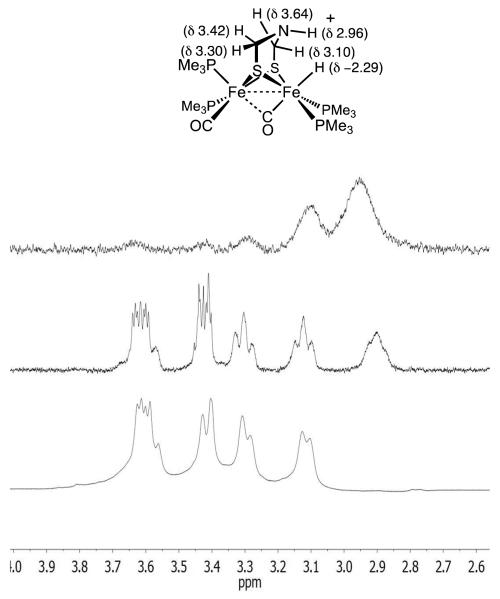

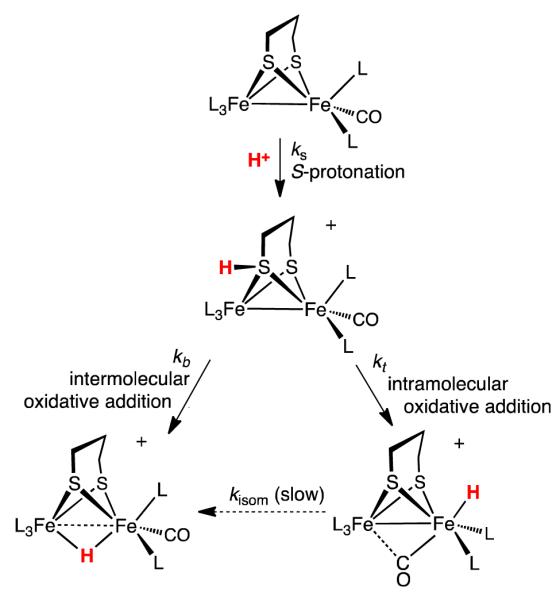

In addition to [μ-H2]+ and [t-H2]+, a third species that is not a hydride is produced by the low-temperature protonation of 2. We note that under these conditions (-90 °C), the H(OEt2)2BArF4 had been fully consumed as indicated by the absence of the signal δ 16.60 as well as signals for free OEt2 (δ 3.46 and 1.16), which can be contrasted with the signals for [H(OEt2)2]+ (δ 4.03 and 1.38; literature values:27 δ 3.85 and 1.32, see Supporting Information). Additional signals are observed at δ 4.6 together with a doublet at δ 2.9, which are tentatively assigned to the S-protonated dithiolate [S-H2]+. The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of this protonated intermediate consists of four singlets. The very small value of JPP is typical related compounds.13 Upon warming the sample to −60 °C, the 31P{1H} and 1H NMR signals assigned to this intermediate disappear concomitant with growth of the signals for both [μ-H2]+ and [t-H2]+ (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

31P{1H} NMR spectra for protonation of Fe2(pdt)(PMe3)4(CO)2 with one equiv of H(OEt2)2BArF4, starting at − 90 °C (bottom). The same solution at −60 °C is shown above. In the − 90 °C spectrum, the four singlets assigned to a S-protonated species ([S-H2]+) are indicated with *. Signals assigned to [t-H2]+ are indicated with o. The two doublets are assigned to [μ-H2]+.

The isomerization of [t-H2]+ to [μ-H2]+ was measured by monitoring the disappearance of the 1H NMR signal for terminal hydride.

The isomerization of [t-H2]+ to [μ-H2]+ was found to be accelerated by acid, a surprising result. Thus, in the presence of 10 equiv of H(OEt2)2BArF4, the isomerization rate increased two-fold at room temperature. The acid-catalyzed isomerization of [t-H2]+ was first order in acid. When the reaction was catalyzed by D(OEt2)2BArF4, incorporation of deuterium in the product was not observed, consistent with the mechanism shown in eq 4.

|

(4) |

The ratio [μ-H2]+/[t-H2]+ from protonation of 2 was found to depend on the ratio [H+]/[2]0 (the product ratio [μ-H2]+/[t-H2]+ was reliably determined because the isomerization of [t-H2]+ into [μ-H2]+ is slow). Thus, at room temperature, protonation of 2 with one equiv of H(OEt2)2BArF4 gave a ~1:1 mixture of [μ-H2]+ and [t-H2]+. In contrast, protonation with 0.5 equiv of H(OEt2)2BArF4 produced only small amounts of [t-H2]+, instead the predominant product was [μ-H2]+. The results of several experiments, summarized in Figure 6, are consistent with pathways to [t-H2]+ and [μ-H2]+ that are first and second order in [2], respectively. A plausible reaction, the apparent rate for which would be second order, involves the transfer of a proton from the S-protonated intermediate [S-H2]+ to the Fe-Fe bond of a second molecule of 2. The product ratio %[μ-H2+]/%[t-H2+] gives a reasonable fit for the two-term rate expression shown in eq 5. In this analysis, kt and kμ are first and second order rate constants for the formation of the terminal and bridging hydrides, respectively.

Figure 6.

Product distribution for the protonation of 2 with various deficiencies of the acid H(OEt2)2BArF4. The fit on the right is for 14.4[Fe2], = %[μ-H2+]/%[t-H2+], where

Competitive Protonation of Fe2(edt)(CO)2(PMe3)4 and Fe2(pdt)(CO)2(PMe3)4

Given that both 1 and 2 protonate directly at the Fe-Fe bond, we investigated their relative kinetic basicities. Control experiments confirmed the absence of intermetallic proton transfer. Thus, the following three reactions did not proceed at observable rates at room temperature: [t-H2]+ + 1, [μ-H2]+ + 1, and [μ-H1]+ + 2. These results are consistent with the slowness of intermetallic proton transfer, as is typical for transition metal hydrides.5,9

When a 1:1 solution of 1 and 2 was treated with one equiv of H(OEt2)2BArF4, we obtained an unexpected result - the products were mostly μ-hydrides, only about 10% of [t-H2]+ was produced. Of the μ-hydride products, the ratio was about 1:3 in favor of [μ-H1]+. Obviously protonation at the terminal vs bridging positions is subject to finely balanced energetics. More specifically, this result indicates that the bridging site in 1 is more kinetically basic than in 2, i.e. kμ1 > kμ2.

Preparation and Protonation of Fe2(adt)(CO)2(PMe3)4

The synthesis of Fe2(adt)(CO)2(PMe3)4 (3) followed straightforwardly from the hexacarbonyl. The amine is brown-yellow, whereas 1 and 2 appear green-brown. Although the IR spectra in the νCO region are identical for 1 and 2, these bands are shifted by 5 cm−1 to higher energy for the adt derivative. At −10 °C in CD2Cl2 solution, the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum shows two sharp signals for the PMe3 ligands. At −90 °C the spectrum exhibits four signals attributed to the slowing of conformational equilibrium of the adt bridge, indicating that the adt complex is more rigid than the pdt analog.

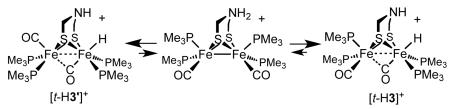

Complex 3 is extremely soluble in pentane, which prevented its complete purification. Since solid samples of 3 were not easily precipitated, we focused on the salts of the corresponding hydride cation. Protonation of crude samples of 3 with H(OEt2)2BArF4 afforded green solutions of the terminal hydride [t-H3]+. Even when performed at room temperature, protonation produced the terminal hydride exclusively under all conditions, unlike the case of 1 and 2. Further evidence for its difference from 1 and 2, 3 efficiently converted to the hydride upon treatment with weak acids, such as NH4PF6.

The 1H NMR spectrum of [t-H3]+ features a multiplet at δ −2.29 (JPH = 100, 55.4, 2.4 Hz), whereas the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum shows four doublets, being centered at δ 31.64, 28.00, 21.38, 12.52 (JPP ~ 38 Hz). The pattern is similar to that for [t-H2]+ (δ 35.8, 30.3, 25.2 17.8; JPP ~33 Hz). The structural simplicity of [t-H3]+ provided an unparalleled opportunity to observe 1H NMR signals for the amine cofactor bound to an diiron hydride. The five protons of the SCH2NHCH2S cofactor are nonequivalent and are well resolved in the 1H NMR spectrum (Figure 7). The D2O-exchangeable signal near δ 2.9 is assigned to NH. The hydride signal also disappeared upon addition of D2O. In a 1-D nOe experiment, irradiation at δ −2.29 showed a strong interaction with this same signal, which suggests that the N-H group is oriented toward the hydride.

Figure 7.

1H NMR spectra in the adt region of a CD2Cl2 solution of [t-H3]+ . Top is the result of 1-D nOe experiment upon irradiation at δ −2.11. Middle and bottom: spectra before and after addition of D2O, respectively (the Fe-H signal also vanishes). The shoulder on the δ 3.6 multiplet arises from [t-H3′]+.

Since little structural information exists on terminal hydrides of diiron dithiolates,11 considerable effort was spent on crystallographic characterization of [t-H3]+. For both the BArF-4 and B(C6F5) )4 salts, we noticed that the crystals were red and or green depending on the growth conditions (original solutions of [t-H3]+ were green). Dissolution of red crystals in CD2Cl2 gave a red-black solution, the 31P{1H} NMR analysis of which indicated variable amounts of a new isomer, labeled [t-H3′]+, which exhibits singlets at δ 23.5 and 7.9. The 1H NMR spectrum showed a triplet at δ −2.8 (JPH = 75.8 Hz), consistent with a symmetrical terminal hydride. The appearance of the symmetrical isomer in the case of [t-H3′]+ but not for the propanedithiolate is attributed to the ability of [t-H3]+ to equilibrate via the transient formation of the ammonium tautomer [N-H3+].

At room temperature, the [t-H3]+/[t-H3′]+ ratio is 2:1, i.e. the all-basal isomer is less stable than the unsym isomer (stated differently, the three stereoisomers, l-[t-H3]+, d-[t-H3]+ and [t-H3′]+, are of equal stability). Faster crystal growths (by vapor diffusion) gave greater amounts of the unsym isomer, whereas slower crystal growths (by solvent diffusion) gave crystals that were often nearly pure all-basal, reflecting its lower solubility (eq 5).

|

(5) |

The mixed salt was solved crystallographically. Despite the presence of both isomers (wholecation disorder), the structure solution established the stereochemistry of the two isomers (Figure 8). Aside from the differing stereochemistry of one PMe3 ligand, the semi-bridging CO is more symmetrical in the unsymmetrical complex [t-H3]+ which has two strong donors in apical positions. In the active site, a thiolate ligand occupies this apical position.

Figure 8.

Structures of the cations in [t-H3]BArF4/[t-H3′]BArF4 showing 50% thermal ellipsoids. Selected distances (Å) and angles (°) for [H3]+ and [H3′]+: Fe1B-Fe2B, 2.660(6); Fe1-Fe2, 2.659(6); O2-C2-Fe2, 152(1); O2B-C2B-Fe2B, 156(4). Fe1-C2, 2.50(1); Fe1B-C2B, 2.46(4).

In solution, [t-H3]+ and [t-H3′]+ are well behaved. Via a first order pathway (t1/2 = 4.5 h, 20 °C), [t-H3]+ converts to [μ-H3]+. The rate of isomerization of [t-H3′]+ was noticeably slower and proceeded via [t-H3]+ (Supporting Information). Addition of strong acids to each hydride results in N-protonation, without loss of H2. The dication [t-H3H]+, which was more readily examined, was deprotonated by water, indicating that it is highly acidic. The 1H NMR spectrum of [t-H3H]+ displays the expected signals, which are only slightly shifted relative to [t-H3]+. The NH2 signals are nonequivalent.

Redox Properties of 1, 2, and 3

Electrochemical measurements confirmed the highly reducing nature of 1 -3. Because the compounds are so reactive, voltammetry was examined on o-difluorobenzene solutions.28 Compounds 1-3 oxidize near −950 mV vs Fc+/0 (Table 2). The oxidations of 1 and 2 are fairly reversible. For comparison, the couple [Fe2(pdt)(CO)4(PMe3)2]0/+ occurs at −0.2 V.29 The oxidation of the amine occurs at potential similar to that for the pdt complex, but the couple is less reversible and appears to be associated with a 2e change. Such effects have been attributed to the coordination of the amine that stabilizes the diferrous state.30

Table 2.

Oxidation Potentials for New Complexes and Related Compounds in o-Difluorobenzene.10

| Compound | E11vs Fc0/+ |

|---|---|

| [Fe2(edt)(CO)4(PMe3)2]0/+ | −0.23a |

| [Fe2(edt)(CO)2(PMe3)4]0/+ ([1]0/+) | −0.950 |

| [Fe2(pdt)(CO)4(PMe3)2]0/+ | −0.20a |

| [Fe2(pdt)(CO)2(PMe3)4]0/+ ([2]0/+) | −0.970 |

| [Fe2(pdt)(CO)2(dppv)2]0/+ | −0.850a |

| [Fe2(adt)(CO)2(PMe3)4]0/+ ([3]0/+) | −0.970 (ipc/ipa = 0.6) |

Reported for CH2Cl2 solutions.

Computational Analysis of Fe2(xdt)(CO)2(PMe3)4 and Protonated Derivatives (xdt = edt, pdt, adt)

Initial DFT calculations analyzed the ground state geometry of 1 and 2. The C2v structure of the edt derivative 1 was well reproduced by the calculations (Figure S1 in Supporting Information) and rotated forms do not correspond to energy minima. For the pdt derivative 2 however, rotated and pseudo-C2v isomers are both stable and very close in energy (0.3 kcal/mol). The rotated structure is unsymmetrical with the CO and phosphine ligands in a geometry best described as trigonal bipyramidal, where one PMe3 and one S atom are the axial ligands, (Figure S2 in Supporting Information). The stabilization of the rotated structure in 2 (vs 1) is due to steric interactions between the central CH2 group of pdt and the iron ligands.

We computed the relative stabilities of the protonated derivatives of 1 and 2 (Scheme S1 in Supporting Information). Three relatively low energy isomers were identified for [H1]+ and [H2]+, which in order of stability are bridging hydrides, the terminal hydrides (5-6 kcal/mol higher in energy), and, 27-29 kcal/mol higher in energy, the S-protonated cations. The S-protonated species are about 10 kcal/mol lower in energy than any CO-protonated isomers, in agreement with the analysis by Pickett and Hall for the protonation of the less basic Fe2(pdt)(CO)4(PMe3)2.19 Notably, S-protonation in 2 stabilizes the pseudo-C2v isomer relative to the rotated form, even if the energy difference remains small (1.2 kcal/mol).

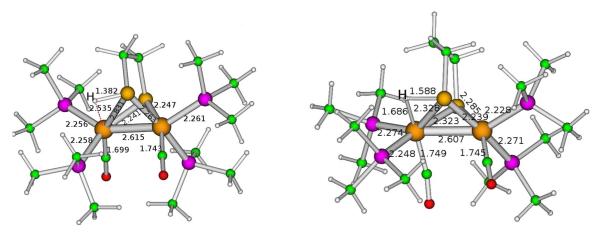

The computed energy barriers for intramolecular proton migration from [S-H1]+ to [t-H1]+ and [S-H2]+ to [t-H2]+ are 11.2 and 1.8 kcal/mol, respectively (Figure 9), a result consistent with the experimental observation that terminal hydride species are kinetically more accessible in complex 2. The difference in the computed energy barriers for intramolecular proton migration in [S-H1]+ and [S-H2]+ can be ascribed to the easier formation of the rotated structure in the pdt-containing complex 2. We were not able to find any low-energy transition state for intramolecular proton migration from [S-H]+ to [μ-H]+ isomers, corroborating the conclusion that fast formation of [μ-H1]+ and [μ-H2]+ species can only take place via intermolecular reactions.

Figure 9.

DFT-optimized structure of the transition state for proton transfer from S to Fe in [Fe2(Hedt)(CO)2(PMe3)4]+ and [Fe2(Hpdt)(CO)2(PMe3)4]+. Note that these images are for the enantiomer of the structures shown elsewhere.

Although not observed, probably because of slow rates of isomerization, according to DFT the most stable protonated derivative of 2 should be the ab/bb isomer of [μ)H2]+, with the (ab)2 isomer 3 kcal/mol higher in energy. The ab/bb and all-basal [t-H2]+ isomers are calculated to be 5.4 and 5.7 kcal/mol less stable than the ab/bb isomer of [μ-H2]+. Although only the ab/bb isomer was observed for [t-H2]+, both isomers for the more readily equilibrated [t-H3]+ were observed experimentally.

Conclusions

Given their very high basicities, compounds 1-3 represent versatile platforms for probing the protonation of diiron dithiolates. Disubstituted diiron(I) dithiolato hexacarbonyls have been exhaustively studied,31 but further substitution has only been effected using very bulky diphosphines.13,23,24,32 Efficient routes to Fe2(xdt)(CO)2(PMe3)4 (xdt = edt, pdt, adt) relies on a new, potentially general photodecarbonylation procedure. The stability, highly solubility, and structural simplicity of the new complexes facilitated low temperature NMR studies of their protonation. Several new mechanistic conclusions can be drawn from these new results.

First, this work shows that Fe2(edt)(CO)2(PMe3)4 converts to the μ-hydride without proceeding via the terminal hydride. Although the terminal hydride [HFe2(edt)(CO)2(PMe3)4]+ is known to be stable, it is not observed under conditions where the bridging hydride is produced quantitatively. This result dispels the possibility that bridging hydrides necessarily arise via the transient terminal hydrides.20

Second, this work proposes that the regiochemistry for the protonation of typical Fe(I)Fe(I) dithiolates hinges on reactivity of S-protonated intermediates. The analysis is enabled by the remarkable kinetic inertness of the isomeric conjugate hydrides. Compounds 1 and 2 are the first examples of dimetallic complexes that competitively give both terminal and bridging hydrides (Scheme 1). S-protonated intermediates have been invoked previously,33 but have not been implicated in the formation of hydrides. The sulfur centers in diiron(I) dithiolates are known susceptible to oxidation34 and alkylation.35 Hydrogen-bonding to sulfur has been characterized in the aminopyridine complex Fe2(pdt)(CO)5(NC5H4-2-NH2) and related compounds.36 The proposed intramolecular proton-transfer mechanism is similar to that proposed for the intramolecular oxidative addition (or tautomerization) of iron(0) thiol complexes to the ferrous thiolato hydride (eq 6).37

Scheme 1.

|

(6) |

One interesting stereochemical detail is that while the two S centers are equivalent sites for protonation, the Fe centers are diastereotopic in the S-protonated intermediate. One consequence is that the rates for proton migration will differ for the two Fe centers (Scheme 2) The newly described acid-catalyzed isomerization of [t-H2]+ to [μ-H2]+ is also consistent with S-protonation, which would weaken the Fe-SH bonds, facilitating turnstile rotation at the FeH(PMe3)2 center. The reaction is analogous to the ability of acids to labilize anionic ligands in Werner complexes.38 The findings reinforce the general observation that metal complexes initially protonate at virtually any site other than the metal39 and that these weakly basic sites can relay the proton to the metal.

Scheme 2.

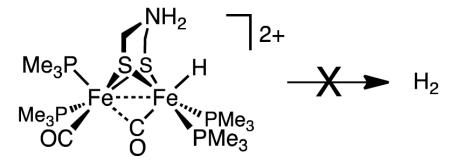

Finally, the behavior of the adt complex 3 differs strongly from that for pdt and edt derivatives - protonation of the azadithiolato complex gives only the terminal hydride and requires only weak acids. Owing to the presence of this relay group, not only is the protonation regioselective (at all temperatures), but also it is reversible, which opens the pathway to a new terminal hydride isomer that is not observed with the edt and pdt derivatives. Protonation of the terminal hydrides affords ammonium hydrides. These species show no tendency to eliminate H2 (eq 7).

|

(7) |

This stability is consistent with the idea that the production as well as the oxidation of H2 are coupled to electron-transfer reactions.32

Summary

In the [FeFe]-hydrogenases, nature employs an amine-containing cofactor to accelerate protonation at a single Fe center of the diiron(I) dithiolato active site. Nonetheless, protonation of related complexes that lack the amine also can occur at a single Fe center.13,15,16,19,40,41 We provide evidence that this regiochemistry results from initial protonation at sulfur followed by proton transfer to one Fe center.

Experimental Section

General methods and apparatus have been recently described.42 Literature methods were followed for the synthesis of Fe2(edt)(CO)6 and Fe2(pdt)(CO)6.43 PMe3 was purchased from Strem. The solution of LiBHEt3 in THF was purchased from Aldrich. Silica gel was purchased from SiliCycle (SiliaFlash® P60, 230-400 mesh). Samples for kinetics were prepared under inert atmosphere. NMR spectra were arrayed on a Varian Unity 500 MHz NMR spectrometer, the probe temperature was pre-regulated to 20 °C; data were analyzed with MestReNova7 software. Nuclear Overhauser enhancement experiments utilized Varian’s NOESY 1-D routine, a transient nOe experiment that is rapid but less quantitative than the steady-state nOe experiment.

Fe2(edt)(CO)2(PMe3)4(1)

In a 50-mL Pyrex Schlenk tube loaded with 250 mg (0.67 mmol) of Fe2(edt)(CO)6 was condensed 5 mL of PMe3. The Schlenk tube was allowed to warm to room temperature while stirring, being careful to repeatedly vent the evolved CO. After 30 min. of stirring, the reaction mixture was irradiated with (and warmed by) a LED lamp (λ = 450 nm). After 48 h of irradiation, the reaction was judged complete by the color change to deep green. Unreacted PMe3 was removed under vacuum to leave green solid residue. The solid residue was extracted into ~100 mL of pentane. The extract was filtered through a pad of Celite, and the green filtrate was evaporated to leave a dark green solid. Analytically pure product was obtained by cooling a saturated pentane solution to −20 °C. Yield: 220 mg (58%). 31P{1H} NMR (CH2Cl2, 5 °C): δ 25.99 (s), 10.78 (s). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 1.84 (br s, SCH2, 4H), 1.23 (br s, PMe3, 36H). IR (CH2Cl2): 1856 (m), 1835 (m) cm−1. Anal. Calcd (found) for C16H40Fe2O3P4S2: C, 34.06 (34.34); H, 7.15 (7.03). Solutions of 1 in CD2Cl2 deposit insoluble material over the course of several hours. IR of [μ-H1]+: νCO = 1944 and 1934 cm−1. Heating (3 days, 60 °C) of a CD2Cl2 solution of [μ-H1]BArF4 in a flame-sealed NMR tube resulted in no change.

Fe2(pdt)(CO)2(PMe3)4 (2)

In 50-mL Pyrex Schlenk tube loaded with 300 mg (0.77 mmol) of Fe2(pdt)(CO)6 was vacuum transferred 5 mL of PMe3. The mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature while stirring, being careful to repeatedly vent the evolved CO. After 30 min. of stirring, the reaction tube was irradiated with an LED lamp (λ = 450 nm) for 48 h. The reaction was judged complete when the color turned deep green. Unreacted PMe3 was removed under vacuum to leave a green solid. This solid was extracted under inert atmosphere into ~100 mL of pentane, and the extracts were filtered through Celite and then evaporated under vacuum. Compound 2 was obtained in analytical purity by crystallization by cooling a saturated pentane solution of the crude solid to −20 °C. Yield: 256 mg (57%). 31P{1H} NMR (CH2Cl2, 15 °C): δ 29.99 (very broad s), 16.28 (very broad s). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 1.96 (broad s, SCH2, 4H), 1.54 (m, SCH2CH2CH2S, 2H), 1.33 (d, PMe3, 36H). IR (CH2Cl2): 1857 (m), 1836 (m) cm−1. Anal. Calcd (found) for C17H42Fe2O3P4S2: C, 35.31 (35.61); H, 7.32 (7.18). For [t-H2]+, 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ −2.2 (JPH = 101, 57, 2.5 Hz). 31 P{1H} NMR: δ 35.8 (d, JPP ~ 33 Hz), 30.3 (d, JPP ~ 33 Hz), 25.2 (d, JPP ~ 33 Hz), 17.8 (d, JPP ~ 33 Hz). Isomerization of [t-H2]+ was monitored in a flame-sealed NMR tube. For [t-H2]+, IR: 1944 (vs), 1883 (m), and 1850 (m) cm−1. When D(OEt2)2BArF4 is used for protonation, the band at 1883 cm−1 shifts to 1866 cm−1 For [μ-H2]+: 31P{1H} NMR: δ 25.8 and 20 (JPP = 42 Hz). 1H NMR: δ −18.8 (JPH = 27.2, 3.4 Hz). IR νCO = 1944, 1933 cm−1.

Fe2(adt)(CO)2(PMe3)4 (3)

A 50-mL Pyrex Schlenk tube charged with 500 mg (1.29 mmol) of Fe2(adt)(CO)6 was distilled 5 mL of PMe3. The mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature while stirring and being careful to repeatedly vent the evolved CO. After 30 min. the reaction tube was irradiated at 450 nm for 48 h. The reaction was judged complete when the solution color became dark brown-yellow. Excess PMe3 was removed under vacuum to leave gold glassy solid. This solid was extracted under inert atmosphere in ~100 mL of pentane, and this solution was filtered through Celite. Pentane was removed to give crude 3 as a dark green-brownish solid. 1H NMR (CH2Cl2, −10 °C): δ 1.20 (d, JPH = 11 Hz, PMe3, 18H), 1.53 (d, JPH = 11Hz, PMe3, 18H), 3.20 (t, CH2NHCH2, 2H), 3.40 (br d, CH2NHCH2, 4H). 31P{1H} NMR (CH2Cl2, −10 °C): δ 12.68 (s, 2P), 25.96 (s, 2P). IR (CH2Cl2): 1860 (m), 1839 (m) cm−1. IR spectra in the νCO region for pure [t-H3]+ and its mixture with ~25% [t-H3′]+ are very similar, consisting of bands at 1945 and 1879 cm−1. Fairly clean samples of 3 can be obtained protonating the crude mixture with excess NH4PF6 and subsequent deprotonation of the resulting terminal hydride with NEt3. To a 10 mL CH2Cl2 solution of 400 mg (0.69 mmol) of 3 was added a 1 mL CH3OH solution of 340 mg of NH4PF6 (2.03 mmol) at room temperature. The resulting deep green solution was stirred for 5 min. before 50 mL of pentanes were added causing precipitation of green solid. The suspension was filtered through a plug of 10 g of Celite, and the solution discarded. The green solid on the top of the plug was washed with 100 mL of pentanes before being extracted into 50 mL of CH2Cl2. The CH2Cl2 solution was concentrated to about 10 mL before addition of about 1 mL (7.17 mmol) of NEt3. The solution was stirred at room temperature for 1 h (the color changed from deep green to brown-yellow over the course of ~ 5 min.) then 100 mL of pentanes were added. The slurry was then filtered through a plug of 10 g of Celite to remove HNEt3PF6 and a red undefined precipitate. The solvent was removed under vacuum to afford 250 mg (61.5 % yield) of a dark solid. Although the sample is cleaner than the crude it still contains and undefined impurity about (5% as judged from 31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy).

[t-HFe2(adt)(CO)2(PMe3)4BArF4 ([t-H3]BArF4 and [t-H3′]BArF4)

A mixture of 450 mg (0.78 mmol) of 3 and 500 mg of H(OEt2)2BArF4 (0.49 mmol) cooled to −78 °C was treated with 10 mL of CH2Cl2. This deep green solution was stirred for 10 min before 40 mL of pentane were added causing precipitation of a green solid. The dark pentane layer was removed by filter cannula. The green product was redissolved in ca. 10 mL of CH2Cl2 and reprecipitated with pentane. This step was repeated twice to give a green solid that was dried under vacuum at room temperature for 1 h. Yield: 642 mg (90% yield based on H(OEt2)2BArF4). 31P{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ 31.64 (d, JPH = 38 Hz, 1P), 28.00 (d, JPH = 38 Hz, 1P), 21.38 (d, JPH = 38 Hz, 1P), 12.52 (d, JPH = 38 Hz, 1P). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ –2.25 (ddd, JPH = 100.1, 55.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 1.43 (d, JPH = 11 Hz, PMe3 18H), 1.60 (d, JPH = 11 Hz, PMe3 9H), 1.79 (d, JPH = 11 Hz, PMe3 9H), 2.93 (t, CH2NHCH2, 1H), 3.15 (t, CHHNHCH2, 1H), 3.33 (t, CH2NHCHH, 1H), 3.45 (m, CHHNHCH2, 1H), 3.64 (m, CH2NHCHH, 1H). IR (both isomers, CH2Cl2): 1945 (m), 1879 (s) cm−1. Note that νCO bands for [μ-H3]+ at 1944 and 1933 cm−1 are much more intense than bands for [t-H3]+. Under inert atmosphere a 5-mL scintillation vial was loaded with 15 mg of [t-H3]BArF4 and 2 mL of a 9:1 mixture of diethyl ether and pentane. Pentane was allowed to diffuse into this vial overnight at −30 °C, affording large red crystals suitable for X-ray characterization. Although in solution these hydrides appear normal, BF −4 and PF6− salts of the hydrides could not be crystallized from CH2Cl2-pentane. Attempts to obtain crystals of BArF4− and B(C6F5)4− salts from CH2Cl2-pentane afforded oils. Calcd (found) for C48H54BF24Fe2NO2P4S2: C, 39.94 (40.04); H, 3.77 (3.65); N, 0.97 (0.86).

Both the BArF24− and BArF20− salts isomerize at similar rates to the bridging hydride. In the case of the BArF24− salt, isomerization was accompanied by the formation of small amounts of unidentified black solid and some [HPMe3]+.

In-situ Preparation of Hydrides

In a J. Young NMR tube, 5 mg of the diiron compound was dissolved in 0.3 mL of CD2Cl2 at room temperature. The sample was sonicated for 2 min. to help dissolve the starting material and degas the solution, then the solution was frozen in liquid nitrogen and evacuated. About 0.2 mL of CD2Cl2 was vacuum transferred on top of the frozen solution as a “buffer” layer (note: this portion of CD2Cl2 was not condensed on the walls of the tube but on top of the frozen sample solution). The NMR tube was then rapidly opened to the air and a freshly prepared solution of 1 equiv of H(OEt2)2BArF4 in 0.2 mL of CD2Cl2 was added by syringe (solutions of H(OEt2)2BArF4 in CD2Cl2 were found to be stable for ca. 90 min. at room temperature before the formation of HArF becomes apparent). The tube was quickly closed and evacuated. The acid solution mainly froze on the walls of the tube. After evacuating the tube, the acid solution (not the sample solution) was allowed to thaw, flow onto, and mix slightly with the CD2Cl2 buffer layer without melting the solution of the diiron complex. The mixture was then frozen and evacuated. The J. Young tube was next moved from the liquid nitrogen bath into a slush of frozen CH2Cl2 where the solution was allowed to slowly thaw (ca. 15 min). After the solvent had completely thawed, the NMR tube was vigorously shaken (within the CH2Cl2 slush bath to maintain low temperatures) to initiate the protonation and quickly transferred into a precooled (-90 °C) NMR probe. The thermal expansion properties differ for the glass and the Teflon such that the valve in J. Young tubes can open at very low temperatures, although under typical conditions the tube is blanketed with N2 from the cryogen. To avoid this problem, most low temperature NMR experiments utilized flame-sealed tubes.

[t-HFe2(adtNH2)(CO)2(PMe3)4](BF4)(BArF20)

A solution of 350 mg (0.28 mmol) of [t-H3]BArF20 in 20 mL of CH2Cl2 was then treated with 0.34 mL of a stock solution of HBF4·OEt2 (1.40 mmol). The deep green solution was stirred for 10 min before 40 mL of pentane were added, causing precipitation of a green solid. The clear pentane layer was removed by filter cannula. The green product was redissolved in ca. 10 mL of CH2Cl2 and reprecipitated with a 1:1 mixture of pentane and diethyl ether. This step was repeated twice to give a green solid that was dried under vacuum at room temperature for 1 h. 31P{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ 31.89 (d, JPH = 42 Hz, 1P), 26,69 (d, JPH = 42 Hz, 1P), 20.35 (d, JPH = 42 Hz, 1P), 13.11 (d, JPH = 42 Hz, 1P). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ –2.07 (dd, JPH = 93.0, 55.4 Hz, 1H), 1.50 (d, JPH = 11 Hz, PMe3 9H), 1.53 (d, JPH = 11 Hz, PMe3 9H), 1.68 (d, JPH = 11 Hz, PMe3 9H), 1.80 (d, JPH = 11 Hz, PMe3 9H), 3.28 (t, CHHNH2CH2, 1H), 3.39 (t, CH2NH2CHH, 1H), 3.96 (m, CHHNH2CH2, 1H), 4.09 (m, CH2NH2CHH, 1H), 7.14 (broad s, CH2NH2CH2, 1H), 8.13(broad s, CH2NH2CH2, 1H).

Electrochemical Measurements

Using a CH Instruments Model 600D Series Electrochemical Analyzer, cyclic voltammograms were recorded on 1,2-C6H4F2 solutions of 1-3 in an inert atmosphere box with glassy carbon working electrode, Pt counter electrode, and silver wire pseudo-reference. Potentials are referenced to Fc+/0, which was included in the solution. Scan rate = 50 mV/s.

Computational Details

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations have been carried with the TURBOMOLE suite of programs.44 A high quality level of theory (B-P86/TZVP45) has been employed to treat explicitly (no effective-core potential is used; inner shell electrons are explicitly treated) the full electronic structure of all atoms of the diiron species investigated. Such DF scheme has been shown to be suitable for investigating hydrogenase models.41,46 All stationary points on the PES have been determined by means of energy gradient techniques and a full vibrational analysis has been carried out to further characterize the nature of each point. Transition state structures have been searched by means of a procedure based on a quasi-Newton-Josephson algorithm.47 As a preliminary step, the geometry optimization of a guess transition state structure is carried out by freezing the molecular degrees of freedom corresponding to the reaction coordinate (RC). After performing the vibrational analysis of the constrained minimum energy structures, the negative eigenmode associated to the RC is followed to locate the true transition state structure, which corresponds to the maximum energy point along the trajectory that joins two adjacent minima (i.e., reactants, products and reaction intermediates).

An implicit treatment of solvent effects (COSMO,48 ε = 9.1, dichloromethane) has been used to evaluate possible polarization phenomena. However, it has been verified that solvent corrected energies do not vary significantly compared to those computed in a vacuum. In light of available experimental data and considering the chemical nature of the ligands, only low-spin forms of FeFe complexes have been considered for DFT calculations. The Resolution of the Identity procedure49 was used for approximating expensive four-center integrals (describing the classical electron-electron repulsive contribution to the total energy) through a combination of two three-center integrals. This is made possible by expanding the density ρ in terms of an atom-centered and very large basis, the auxiliary basis set.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant GM61153).

Footnotes

Supporting Information 1H NMR, 31P NMR, and IR spectra, voltammetry, X-ray crystallographic data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Notes The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Tard C, Pickett CJ. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:2245. doi: 10.1021/cr800542q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Gloaguen F, Rauchfuss TB. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:100. doi: 10.1039/b801796b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Silakov A, Wenk B, Reijerse E, Lubitz W. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009;11:6592. doi: 10.1039/b905841a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Nicolet Y, de Lacey AL, Vernede X, Fernandez VM, Hatchikian EC, Fontecilla-Camps JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:1596. doi: 10.1021/ja0020963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kramarz KW, Norton JR. Prog. Inorg. Chem. 1994;42:1. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Nicolet Y, Lemon BJ, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Peters JW. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:138. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01536-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Ziegler W, Umland H, Behrens U. J. Organomet. Chem. 1988;344:235. [Google Scholar]; Olsen MT, Bruschi M, De Gioia L, Rauchfuss TB, Wilson SR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12021. doi: 10.1021/ja802268p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hsieh C-H, Erdem ñ. F., Harman SD, Singleton ML, Reijerse E, Lubitz W, Popescu CV, Reibenspies JH, Brothers SM, Hall MB, Darensbourg MY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:13089. doi: 10.1021/ja304866r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Tye JW, Darensbourg MY, Hall MB. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:1552. doi: 10.1021/ic051231f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Tschierlei S, Ott S, Lomoth R. Ener. & Envir. Sci. 2011;4:2340. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Felton GAN, Mebi CA, Petro BJ, Vannucci AK, Evans DH, Glass RS, Lichtenberger DL. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009;694:2681. [Google Scholar]

- (11).van der Vlugt JI, Rauchfuss TB, Whaley CM, Wilson SR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:16012. doi: 10.1021/ja055475a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Barton BE, Olsen MT, Rauchfuss TB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16834. doi: 10.1021/ja8057666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Barton BE, Rauchfuss TB. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:2261. doi: 10.1021/ic800030y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Carroll ME, Barton BE, Rauchfuss TB, Carroll PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134 doi: 10.1021/ja309216v. 00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Ezzaher S, Capon J-F, Gloaguen F, Pétillon FY, Schollhammer P, Talarmin J, Pichon R, Kervarec N. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:3426. doi: 10.1021/ic0703124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Adam FI, Hogarth G, Kabir SE, Richards I. C. R. Chim. 2008;11:890. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Hogarth G, Richards I. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2007;10:66. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wright JA, Pickett CJ. Chem. Commun. 2009:5719. doi: 10.1039/b912499c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jablonskytė A, Wright JA, Pickett CJ. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:3026. doi: 10.1039/b923191a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Liu C, Peck JNT, Wright JA, Pickett CJ, Hall MB. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2010;2011:1080. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Olsen MT, Gray DL, Rauchfuss TB, De Gioia L, Zampella G. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:6554. doi: 10.1039/c1cc10858a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Lyon EJ, Georgakaki IP, Reibenspies JH, Darensbourg MY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:3268. doi: 10.1021/ja003147z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Zampella G, Bruschi M, Fantucci P, Razavet M, Pickett CJ, De Gioia L. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:509. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Justice AK, Zampella G, De Gioia L, Rauchfuss TB. Chem. Commun. 2007:2019. doi: 10.1039/b700754j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Justice AK, Zampella G, De Gioia L, Rauchfuss TB, van der Vlugt JI, Wilson SR. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:1655. doi: 10.1021/ic0618706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Zhao X, Georgakaki IP, Miller ML, Mejia-Rodriguez R, Chiang C-Y, Darensbourg MY. Inorg. Chem. 2002;41:3917. doi: 10.1021/ic020237r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Silakov A, Kamp C, Reijerse E, Happe T, Lubitz W. Biochemistry. 2009;48:7780. doi: 10.1021/bi9009105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Brookhart M, Grant B, Volpe AF. Organometallics. 1992;11:3920. [Google Scholar]

- (28).O’Toole TR, Younathan JN, Sullivan BP, Meyer TJ. Inorg. Chem. 1989;28:3923. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Wang W, Rauchfuss TB, Bertini L, Zampella G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:4525. doi: 10.1021/ja211778j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Olsen MT, Rauchfuss TB, Wilson SR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:17733. doi: 10.1021/ja103998v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Fauvel K, Mathieu R, Poilblanc R. Inorg. Chem. 1976;15:976. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Camara JM, Rauchfuss TB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8098. doi: 10.1021/ja201731q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Camara JM, Rauchfuss TB. Nature Chem. 2012;4:26. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Apfel U-P, Troegel D, Halpin Y, Tschierlei S, Uhlemann U, Görls H, Schmitt M, Popp J, Dunne P, Venkatesan M, Coey M, Rudolph M, Vos JG, Tacke R, Weigand W. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:10117. doi: 10.1021/ic101399k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dong W, Wang M, Liu X, Jin K, Li G, Wang F, Sun L. Chem. Commun. 2006:305. doi: 10.1039/b513270c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ezzaher S, Gogoll A, Bruhn C, Ott S. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:5775. doi: 10.1039/c0cc00724b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Kramer A, Lingnau R, Lorenz IP, Mayer HA. Chem. Ber. 1990;123:1821. [Google Scholar]; Liu T, Li B, Singleton ML, Hall MB, Darensbourg MY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8296. doi: 10.1021/ja9016528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Windhager J, Seidel RA, Apfel U-P, Goerls H, Linti G, Weigand W. Chem. Biodiversity. 2008;5:2023. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200890185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Zhao X, Chiang C-Y, Miller ML, Rampersad MV, Darensbourg MY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:518. doi: 10.1021/ja0280168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Feng Y-N, Xu F-F, Chen R-P, Wen N, Li Z-H, Du S-W. J. Organomet. Chem. 2012;717:211. [Google Scholar]; Wang Z, Jiang W, Liu J, Jiang W, Wang Y, Akermark B, Sun L. J. Organomet. Chem. 2008;693:2828. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Liaw W-F, Kim C, Darensbourg MY, Rheingold AL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:3591. [Google Scholar]; Wander SA, Reibenspies JH, Kim JS, Darensbourg MY. Inorg. Chem. 1994;33:1421. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Basolo F, Pearson RG. Mechanisms of Inorganic Reactions. J. Wiley; New York: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Pribich DC, Rosenberg E. Organometallics. 1988;7:1741. [Google Scholar]; Hodali HA, Shriver DF. Inorg. Chem. 1979;18:1236. [Google Scholar]; Keister JB. J. Organomet. Chem. 1980;190:C36. [Google Scholar]; Femoni C, Iapalucci MC, Longoni G, Zacchini S, Zarra S. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:1599. doi: 10.1021/ic802015f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Ezzaher S, Capon J-F, Gloaguen F, Kervarec N, Pétillon FY, Pichon R, Schollhammer P, Talarmin J. C. R. Chim. 2008;11:906. doi: 10.1021/ic0703124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Barton BE, Zampella G, Justice AK, De Gioia L, Rauchfuss TB, Wilson SR. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:3011. doi: 10.1039/b910147k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Morvan D, Capon J-F, Gloaguen F, Pétillon FY, Schollhammer P, Talarmin J, Yaouanc J-J, Michaud F, Kervarec N. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009;694:2801. [Google Scholar]; Orain P-Y, Capon J-F, Kervarec N, Gloaguen F, Pétillon F, Pichon R, Schollhammer P, Talarmin J. Dalton Trans. 2007:3754. doi: 10.1039/b709287c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Orain P-Y, Capon J-F, Gloaguen F, Pétillon FY, Schollhammer P, Talarmin J, Zampella G, De Gioia L, Roisnel T. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:5003. doi: 10.1021/ic100108h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Zampella G, Fantucci P, De Gioia L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:10909. doi: 10.1021/ja902727z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Schilter D, Nilges MJ, Chakrabarti M, Lindahl PA, Rauchfuss TB, Stein M. Inorg. Chem. 2012;51:2338–2348. doi: 10.1021/ic202329y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Mack AE, Rauchfuss TB. Inorg. Synth. 2011;35:142. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Ahlrichs R, Baer M, Haeser M, Horn H, Koelmel C. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1989;162:165. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Becke AD. Phys. Rev. A: Gen. Phys. 1988;38:3098. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Perdew JP. Phys. Rev. B. 1986;33:8822. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.33.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Bertini L, Greco C, Bruschi M, Fantucci P, De Gioia L. Organometallics. 2010;29:2013. [Google Scholar]; Siegbahn PEM, Tye JW, Hall MB. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:4414. doi: 10.1021/cr050185y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zampella G, Bruschi M, Fantucci P, De Gioia L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13180. doi: 10.1021/ja0508424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zampella G, Greco C, Fantucci P, De Gioia L. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:4109. doi: 10.1021/ic051986m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zampella G, Fantucci P, De Gioia L. Chem. Commun. 2010:8824. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02821e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Jensen F. Introduction to Computational Chemistry. Wiley; Chichester: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Schafer A, Klamt A, Sattel D, Lohrenz JCW, Eckert F. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2000:2187. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Eichkorn K, Weigend F, Treutler O, Ahlrichs R. Theor. Chem. Acc. 1997;97:119. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.