Abstract

Stereotype threat is the unpleasant psychological experience of confronting negative stereotypes about race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or social status.

Hundreds of published studies show how the experience of stereotype threat can impair intellectual functioning and interfere with test and school performance. Numerous published interventions derived from this research have improved the performance and motivation of individuals targeted by low-ability stereotypes.

Stereotype threat theory and research provide a useful lens for understanding and reducing the negative health consequences of interracial interactions for African Americans and members of similarly stigmatized minority groups. Here we summarize the educational outcomes of stereotype threat and examine the implications of stereotype threat for health and health-related behaviors.

“Some patients, though conscious that their condition is perilous, recover their health simply through their contentment with the goodness of the physician.”

—Hippocrates (460–400 BC)1a

HIPPOCRATES COULD NOT have envisioned the advances that would transform medicine from an art depending entirely on the human touch to a science built on empirically tested intervention. Yet modern physicians still emphasize the Hippocratic prescription for empathetic and humane treatment of patients, and research confirms that they are right to do so: the quality of patient–provider relations, even in the modern era, remains a significant influence on patient outcomes.1b Indeed, research consistently finds that the way patients and their health care providers interact can matter more than even the training or expertise of the doctors and medical staff who treat them. Interaction quality affects how well patients understand information presented during visits, the amount of pertinent information they later recall, their satisfaction with their treatment, and their adherence to the recommended treatment regimen.2,3 When interactions between care providers and their patients are stressful, unpleasant, or disrespectful, patient health often suffers.1b–5 Most of us can report at least some instances of negative interactions with our health care providers, but members of disadvantaged groups—African Americans, Latinos, the poor, and others—appear to be particularly at risk for unpleasant interactions in the health care system, and this likely contributes to the consistent pattern of poorer health among these groups.4,5

Thousands of studies have documented racial disparities in medical care, which an Institute of Medicine panel defines as “racial or ethnic differences in the quality of health care that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of the intervention.”5(pp3–4) Although some of these disparities occur because racial minorities tend to receive care in underresourced health care facilities,5,6 racial disparities also exist in high-quality health care facilities.5,7

Research demonstrates the existence of unconscious or unintentional bias on the part of health care providers toward cultural minorities and show its contribution to racial disparities in health care outcomes.5,8,9 For example, African American patients are less likely than Whites to receive important medications or surgical procedures, even when they present with identical conditions, and this is directly related to higher rates of mortality.5 Yet provider bias does not fully explain why African American patients tend to be less active in their own care, are less likely than their White counterparts to adhere to treatment plans, have poorer control of their blood sugar, exercise less frequently, and so on.10,11 Part of the answer is rooted in the negative cultural stereotypes that frequently confront African American and other minority patients when they interact with their health care providers.

STEREOTYPE THREAT

Interactions between patients and health care providers may induce stereotype threat, a phenomenon shown by extensive psychological research to generate negative effects in interpersonal contexts, including the classroom and the workplace.12 First identified by Steele and Aronson in 1995,13 stereotype threat can be defined as a disruptive psychological state that people experience when they feel at risk for confirming a negative stereotype associated with their social identity—their race, gender, ethnicity, social class, sexual orientation, and so on. The phenomenon has been studied most extensively in education contexts, where it has been found to play a significant role in the gender gap in mathematics and in the test score gap between African American and White students. More than 200 published experiments show that situations that increase the evaluative scrutiny of ability (e.g., presenting a task as diagnostic of intelligence) or the salience of social identity (e.g., asking test takers to indicate their race or gender on the test or seating students in mixed-gender or -race groups) can impair performance on tests among students who belong to groups suspected of inferiority.

In the first published experiments on stereotype threat,13 African American and White college students were given a challenging section of the verbal Graduate Record Exam. Half of these test takers were told that the purpose of the test was to measure their verbal intelligence; half were told that the purpose was not to measure ability but rather to examine the process of verbal problem solving. Changing the test description had no effect on the White test takers but markedly affected the experience of the African American students; those in the verbal intelligence condition showed evidence of thinking and worrying about stereotypes about their group and correctly answered about half as many items as test takers in all other conditions of the study.

Subsequent experiments suggest that stereotype threat can impair the cognitive performance of virtually any group that is targeted by ability stereotypes. For example, White men with extremely strong math skills performed significantly worse than control participants on a mathematics test if forewarned that their performance would be compared with that of Asians, a group stereotypically portrayed as mathematically gifted.14 Stereotype threat appears to impair performance by inducing physiological stress and by prompting attempts at both behavioral and emotional regulation—all of which, independently or in concert, have the effect of consuming cognitive resources needed for intellectual functioning.15,16 No evidence suggests that stereotype threat impairs test performance simply by prompting test takers to withdraw effort; indeed, stereotype threat appears to increase effort and arousal, reflecting the desire to disprove the negative stereotype—or prove oneself—by performing well.17,18 The problem is that extra effort is not particularly helpful when individuals are trying to solve complex tasks; frequently, trying harder on complex tasks impairs performance.19 Chronic exposure to stereotype threat can result in avoidance of threatening situations and, through this withdrawal from the domain, result in lower grades and test scores,20 but the immediate effects of stereotype threat appear to be vigilance, arousal, impaired self-regulation, and impaired working memory, all of which, alone or in combination, are known to inhibit intellectual performance.15,21

The implications of this research are straightforward: racial differences in academic performance are, to a significant degree, influenced by the nature of situations and by the way individuals respond to them. These differences can be addressed by changing settings and procedures to reduce the triggers of threat or by targeted interventions that help individuals cope with threats when they arise. Several surprisingly simple and short-term field interventions have produced substantial and lasting improvements in test scores, engagement, and grades among students from traditionally low-performing groups.22–25 Such findings raise the possibility that health and health care disparities could be similarly understood and addressed by considering how stereotype threat may strain the relations between patients and their care providers.26,27

Harmful Effects

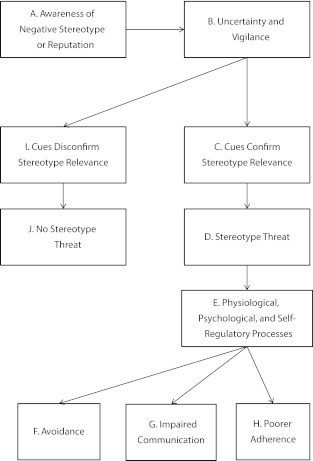

Efforts to ameliorate stereotype threat in health care contexts should be grounded in an understanding of how it gives rise to difficulties between providers and minority patients. Figure 1 illustrates the processes by which stereotype threat might contribute to racial minority patients’ health problems. The process begins with patients’ awareness that they belong to a group that is negatively stereotyped (Figure 1, box A). This awareness leads potential targets of stereotypes to be vigilant for cues that the stereotype is relevant (Figure 1, box B). Quite often these cues are unclear, and patients will experience uncertainty about whether they are being viewed through the lens of a stereotype. If the cues confirm the relevance of the negative stereotype (Figure 1, box C), then stereotype threat is aroused (Figure 1, box D).

FIGURE 1—

The process of stereotype threat in clinical interactions.

It is important to recognize that whether or not health care providers explicitly hold or endorse stereotypes about members of disadvantaged groups, they, like anyone in the culture, are aware of common negative stereotypes (e.g., African Americans are unintelligent, poor people are unhealthy). Because of this, they are capable of unintended, nonverbal bias in their interactions with their patients that, for the patient, can be a cue that confirms the relevance of the stereotype (Figure 1, box C). Research confirms that health care providers stereotype their patients28 and that patients sense this bias and, as a result, feel dissatisfied with the care they receive.29 Yet the experience of stereotype threat does not require any actual prejudice or bias—implicit or explicit—to be manifested; targets can feel devalued by their interaction partners merely as a function of interacting across racial, ethnic, or other social identity divides.30 Thus the minority patient can feel a sense of threat without ever encountering unfair or unkind treatment. Research suggests that such feelings are commonplace among minority patients.26

The experience of stereotype threat has been shown to have direct negative effects on physiological, psychological, and self-regulatory processes that can contribute to ill health. For example, laboratory experiments find that stereotype threat elevates blood pressure, induces anxiety, and increases aggressive behavior, overeating, and a host of other failures of self-regulation.27,31,32 The importance of such direct effects is clear, but stereotype threat also poses risks that may be less obvious, by complicating social interactions and relationships between patients and their providers.

Avoidance of health care.

To receive proper care, patients must seek it. Yet if stereotype threat creates an unpleasant social climate, patients may avoid their providers. Minority group members who perceive discrimination and report higher levels of mistrust are the patients most likely to miss medical appointments and delay needed or preventive medical care.33–36 These findings are paralleled among African American students preparing for evaluations of their intellectual abilities.37 We tend to avoid situations where we feel unwelcome or where we expect devaluation. The implications are self-evident: if minority patients avoid interacting with health care providers, they place themselves at risk for failing to arrest medical conditions before they become serious, and they will be less likely to receive appropriate care.

Communication with health care providers.

Even if patients do not avoid their providers, ineffective communication can hinder their care. Providers need to know medical histories, habits, and symptoms to offer the most appropriate course of treatment. If a patient is experiencing stereotype threat, communication can be compromised in several ways. For example, experiments in which Whites interview African American or White job applicants have found that interracial interviews tend to be briefer, less warm, and less comfortable (for both parties) than are same-race interactions.38 Similar discomfort can compromise a caregiver’s ability to provide and obtain information critical to the patient’s treatment. Stereotype threat reliably induces arousal and anxiety, which impair cognitive performance and working memory. This can compromise the communication process; minority patients may ineffectively communicate important information to providers or fail to understand and remember the content of important conversations.15

Similarly, stereotype threat may influence what patients share with their providers. Studies show that worries about confirming stereotypes significantly influence how individuals present themselves. Specifically, students under stereotype threat will change their self-descriptions (their self-reported likes, dislikes, and habits) to project a self-image that refutes stereotypes.13,39 One can well imagine that patients who feel at risk for devaluation might not truthfully disclose pertinent information, say, about exercise or dietary habits, if that information casts them in a negative, stereotype-confirming light. Stereotype threat may therefore help explain why non-Whites have been shown to be more likely than Whites to overreport cancer-screening behavior.40,41 Stereotype threat may also help explain why clinical interactions appear to be of lower quality when they occur across racial lines—why they are of shorter duration, are less pleasant, and are characterized by less patient involvement and shared decision-making.42,43 Poor communication and less participation in decision-making predict a variety of negative outcomes, such as poor adherence to treatment, utilization of services, self-management, and recovery.26

Although tensions may arise from situational forces such as stereotype threat, people are apt to lay the blame for unpleasant interactions on their interaction partners. Patients may characterize their providers as prejudiced,44 which will likely further erode trust and warmth and increase the likelihood of avoidance behaviors. For providers, unpleasant, strained interactions and their effects on patient behavior may reinforce unflattering racial stereotypes. Both of these effects can perpetuate a vicious cycle, whereby contact serves to degrade the quality of the patient–provider relationship.

Adherence to treatment plan.

African Americans and other minorities tend to be less likely than others to adhere to prescribed treatment plans. How might stereotype threat contribute to nonadherence? First, if the patient fails to adequately process information because an interaction arouses anxiety, he or she may misunderstand the nature or the importance of recommendations, or, alternatively, have difficulty later recalling vital information. In addition to suffering impaired performance on tests, participants in experiments on stereotype threat exhibit significantly worse recall for words presented during a task if a stereotype was activated during a testing session, presumably because they were devoting cognitive resources to contending with stereotype threat.45

Second, because stereotype threat engenders mistrust, minority patients may hear, understand, and recall information and feedback, yet discount it because it is seen as biased or threatening. A frequent finding in stereotype threat experiments, for example, is that students exposed to stereotypes are more likely to discount the validity of tests they take and the evaluations they receive and to question the motives of those delivering the feedback.13,19,37

Harm Reduction

Research on the role of stereotype threat in racial health and health care disparities is urgently needed. Federal guidelines for improving cultural competence and sensitivity exist,46 but they lack clear implementation strategies and are not supported by empirically validated training programs for their use. It is therefore difficult to ensure that such guidelines will be effective in addressing the kind of negative spirals in patient–provider relationships that have been described. Bias reduction at the institutional and individual levels remains both a practical and a theoretical problem to be solved.47,48

In advance of such research, relatively small, concrete changes based on existing evidence can reduce the negative effects of stereotype threat on racial minority patients. These changes are designed to provide cues that disconfirm the relevance of negative stereotypes (Figure 1, box A) or reduce negative physiological and psychological processes, such as anxiety (Figure 1, box E), caused by such cues.49–53

Eliminate prejudice, discrimination, and disrespectful treatment by clinical and nonclinical staff.

Several controlled experiments have shown that prejudice and discrimination can activate stereotype threat and impair performance.54,55 Unfortunately, studies have found a high prevalence of discrimination in health care as experienced by racial minorities56 and extensive evidence that minority patients believe health care providers and nonclinical staff see them as unintelligent and less worthy of good care because of their race or ethnicity.49,50,53,57 Nonclinical staff can contribute significantly to minority patients’ negative experiences receiving care. Indeed, results from a qualitative study of African American, Latino, Native American, and Pacific Islander patients found that their principal concerns about poor treatment and racial bias arose primarily from how they were treated by nonphysician staff.57 This suggests that a whole-clinic approach should be developed to combat perceptions of racial discrimination and disrespect. This might include implementing systemwide training programs to improve employees’ communication skills and structural changes that recognize the importance of employees’ communication skills,48,58,59 as well as auditing for discriminatory or disrespectful behavior by staff.

Even absent social identity threats, interactions in doctors’ offices and hospitals can be less than interpersonally uplifting. Impressions of prejudiced medical staff could be reduced by recognizing and acting on the fact that all people, regardless of race or class, prefer friendliness and compassion to brusqueness, prefer being greeted with inquiries into their well-being than with a demand for their health insurance card, and so on. Common courtesy and warmth go a long way toward reducing the degree to which patients feel stereotyped.

Provide cues that minority racial groups are valued.

The likelihood of stereotype threat is reduced in the presence of contextual cues that convey the high value of members of minority race groups. One powerful cue is the presence of racial minority role models who exhibit counterstereotypical traits and behaviors. Several experiments have shown that the effects of stereotype threat on performance can be reduced or eliminated when individuals are aware of highly competent role models from their own gender or racial group (e.g., Barack Obama, women who excel in math).60–64 In several experiments, reading about professionally successful women reduced the effect of stereotype threat on women’s performance on math and science tests.62,65,66

This research underscores the importance of hiring racial minority employees to occupy respected positions in the health care setting. This might include having more minority individuals in high-status positions, as well as making efforts to confer greater status on roles that tend to be less prestigious—nurses, aides, patient care technicians, community health workers, and the like. Clinics and hospitals could also create “virtual role models” by decorating public spaces with images of successful racial minority individuals.

Studies have also found that cues indicating high fairness (i.e., providing information about the existence of auditing practices that guard against discrimination) increase trust and reduce feelings of threat among African American professionals, even in settings with features known to trigger stereotype threat.67 Health care organizations, then, might want to send clear signals (perhaps via posted mission statements and solicitations of patient feedback) that make explicit and implicit the goal of providing high-quality care for patients from all backgrounds.

Reduce patients’ anxiety.

Stereotype threat impairs performance by arousing anxiety, negative emotions, and negative thoughts about being judged as inferior.18,68,69 Clinical and nonclinical staff might be taught to be attuned to such feelings in their patients and to offer assurance that anxiety in the setting is perfectly normal. Staff can also suggest coping techniques (e.g., bring a friend or family member to the visit, bring prepared questions). Similarly, for a patient who has had difficulty adhering to treatment, the provider can reassure the patient by stressing the normality of such problems for patients of all backgrounds, then work with the patient to identify barriers to adherence and concrete plans to overcome them.

Growing evidence suggests that environmental cues can moderate anxiety and thus can be used to reduce stereotype threat. For example, a recent study found that the scent of vanilla, which is perceived to be calming, eliminated the effect of stereotype threat on consumer decision-making by reducing individuals’ anxiety.70 Research on healing environments demonstrates how noise reduction, soothing music, views of nature, and daylight can reduce stress for patients.71 These types of ambient changes may lessen the anxiety of stereotype threat, send cues that patients are valued, and undercut the belief held by some minority patients that they are receiving inferior care.

Help patients focus on their strengths and successes.

Focusing on one’s valued characteristics or strengths—known as self-affirmation—can also reduce the negative effects of stereotype threat on performance.24,72,73 In 2 studies, African American students who were randomly assigned to self-affirm (i.e., write briefly about their important values) earned higher grades during the semester than did control participants and were less likely to perceive themselves in terms of racial stereotypes.24 Notably, the effects of this 15-minute writing exercise persisted for 2 years.73 Moreover, whereas levels of student trust for teachers declined over time among African American students in the control group, the students who performed the self-affirmation exercise did not experience this erosion of trust.

Such findings suggest that environmental cues and social interactions capable of affirming self-worth could similarly be important in the health care setting. For instance, in discussing a health problem that will require significant behavioral change, the physician might ask the patient to talk about challenges that have been overcome and encourage reflection on the strengths that will be helpful in ensuring adherence to the new health regimen. Expressing curiosity about a patient’s individuality and strengths is an excellent way to assuage the patient’s concerns about being viewed stereotypically, improving the doctor–patient relationship while also identifying and affirming the exact qualities required for adherence and treatment success.

Train clinical staff to give effective critical feedback to patients.

Studies conducted outside of health care have shown that critical feedback can be particularly threatening for members of minority groups. Rather than being perceived as helpful ideas for improvement, feedback can evoke suspicions that one is being viewed through the lens of a negative stereotype.74 Qualitative studies of racial and ethnic minority patients have similar results. For example, a provider’s attempt to discuss issues of obesity, diet, alcohol, and smoking have been shown to arouse suspicions of prejudice and ethnic stereotyping.57

Reports on experiments conducted in academic settings describe more and less productive ways of framing needed feedback. The most productive way to deliver feedback to minority students is to communicate high performance standards coupled with assurance that the student is capable of meeting those standards. Invoking high performance standards tells the student that any apparent harshness in judgment stems from a deep concern with quality, reducing the likelihood that the feedback will be interpreted as evidence of prejudice (e.g., “He doesn’t think I’m a bad writer because I’m African American; he’s just a stickler for grammatically perfect sentences”). Invoking high standards with assurance that the student is capable of meeting them produces the highest levels of motivation and follow-through—far higher than when critical feedback is either straightforwardly negative or sugarcoated with praise.74,75

Clinicians with patients who need to make lifestyle changes might do well to frame advice positively, for example, “I set a high bar for my patients because I want them to enjoy great health. Our conversation convinces me you’re up to the challenge of making the changes we discussed.” This style of feedback is likelier to help patients accept and adhere to treatment protocols than would a simple delivery of a set of recommendations or admonitions.75

Provide clearly written information, instructions, and explanations.

Providing written documentation and instructions that combine standardized information with information tailored to the needs of the patient may help overcome the recall and comprehension problems associated with stereotype threat and therefore improve adherence. Moreover, referring to a printed, standardized information sheet in the clinical encounter can convey to minority patients that they are receiving the same information that nonminority patients receive. If the standardized information outlines a range of potential treatment options for patients with a given diagnosis, it may help alleviate suspicions that better, more expensive treatments are offered only to nonminority patients. Information tailored to the specific patient can be included to add a personal touch to the interaction and signal that the patient, although being given the same options as other patients, is perceived by the physician as an individual, not simply one among many patients or a stereotypical member of a minority group.

CONCLUSIONS

What is true in the world of education is also true in the world of medicine: interactions between people matter a great deal. Situations that threaten the fundamental human motives of inclusion and respect can, through several processes, undermine health just as surely as they spoil academic performance and motivation. Research and theory on stereotype threat provide a useful lens through which to examine the interactions between people from different social groups, which when strained can compromise both the education and the health of individuals with stigmatized identities. The good news is that interventions can be effective; successes in the education realm give us hope for similar progress against the troubling problem of health disparities. The recommendations we offer have proven useful in the academic world, where they have often dramatically improved the learning and performance of African Americans and other minority students.

More research is needed to validate the effectiveness of these suggested remedies to stereotype threat in clinical settings and to develop new ways to minimize unpleasant social interactions, but we are confident that Hippocrates’ advice will never become irrelevant and that improving interpersonal relationships between care providers and patients will become an important front for combating health disparities.

Acknowledgments

The research was made possible by grants from the Spencer Foundation and the National Science Foundation to Joshua Aronson.

Note. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was required because no human participants were involved.

References

- 1a.Hippocrates , Precepts VI : Reiser SJ, Dyck AJ, Curran WJ, Ethics in Medicine: Historical Perspectives and Contemporary Concerns. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1977:5 [Google Scholar]

- 1b.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152(9):1423–1433 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartlett EE, Grayson M, Barker R, Levine DM, Golden A, Libber S. The effects of physician communications skills on patient satisfaction; recall, and adherence. J Chronic Dis. 1984;37(9–10):755–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinman J. Doctor–patient interaction: psychosocial aspects. : Smelser NJ, Baltes PB, International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Oxford, UK: Elsevier; 2004:3816–3821 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper LA, Beach MC, Johnson RL, Inui TS. Delving below the surface. Understanding how race and ethnicity influence relationships in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(suppl 1):S21–S27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparites in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker DW, Nerenz Det al. Disparities in health care are driven by where minority patients seek care: examination of the hospital quality alliance measures. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1233–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trivedi AN, Grebla RC, Wright SM, Washington DL. Despite improved quality of care in the Veterans Affairs health system, racial disparity persists for important clinical outcomes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):707–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgess DJ, Fu SS, van Ryn M. Why do providers contribute to disparities and what can be done about it? J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(11):1154–1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Ryn M, Fu SS. Paved with good intentions: do public health and human service providers contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):248–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams AS, Trinacty CM, Zhang Fet al. Medication adherence and racial differences in A1C control. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(5):916–921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saha S, Freeman M, Toure J, Tippens KM, Weeks C, Ibrahim S. Racial and ethnic disparities in the VA health care system: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):654–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aronson J, McGlone MS. Stereotype and social identity threat. : Nelson T, The Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2008:153–178 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(5):797–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aronson J, Lustina MJ, Good C, Keough K, Steele CM, Brown J. When White men can’t do math: necessary and sufficient factors in stereotype threat. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1999;35(1):29–46 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmader T, Johns M, Forbes C. An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Psychol Rev. 2008;115(2):336–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johns M, Inzlicht M, Schmader T. Stereotype threat and executive resource depletion: examining the influence of emotion regulation. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2008;137(4):691–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jamieson JP, Harkins SG. Mere effort and stereotype threat performance effects. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;93(4):544–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Brien LT, Crandall CS. Stereotype threat and arousal: effects on women’s math performance. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2003;29(6):782–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aronson J. Stereotype threat: contending and coping with unnerving expectations. : Aronson J, Improving Academic Achievement: Impact of Psychological Factors on Education. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massey DS, Fischer MJ. Stereotype threat and academic performance: new findings from a racially diverse sample of freshman. DuBois Rev. 2005;2(1):45–67 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beilock SL, Rydell RJ, McConnell AR. Stereotype threat and working memory: mechanisms, alleviation, and spill-over. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2007;136(2):256–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aronson J, Fried CB, Good C. Reducing the effects of stereotype threat on African American college students by shaping theories of intelligence. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2002;38(2):113–125 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Good C, Aronson J, Inzlicht M. Improving adolescents’ standardized test performance: an intervention to reduce the effects of stereotype threat. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2003;24(6):645–662 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen GL, Garcia J, Apfel N, Master A. Reducing the racial achievement gap: a social-psychological intervention. Science. 2006;313(5791):1307–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walton GM, Cohen GL. A question of belonging: race, social fit, and achievement. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(1):82–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burgess DJ, Warren J, Phelan S, Dovidio J, van Ryn M. Stereotype threat and health disparities: what medical educators and future physicians need to know. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(suppl 2):S169–S177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phelan SM. Evaluating the Implications of Stigma-Induced Identity Threat for Health and Health Care [dissertation] Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race, and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(6):813–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Penner LA, Dovidio JF, West TVet al. Aversive racism and medical interactions with Black patients: a field study. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2010;46(2):436–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Major B, Quinton WJ, McCoy SK. Antecedents and consequences of attributions to discrimination: theoretical and empirical advances. : Zanna MP, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. San Diego: Academic Press; 2002;34:251–330 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blascovich J, Spencer SJ, Quinn DM, Steele CM. African Americans and high blood pressure: the role of stereotype threat. Psychol Sci. 2001;12(3):225–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inzlicht M, Kang SK. Stereotype threat spillover: how coping with threats to social identity affects, aggression, eating, decision-making, and attention. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;99(3):467–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burgess DJ, Ding Y, Hargreaves M, van Ryn M, Phelan S. The association between perceived discrimination and underutilization of needed medical and mental health care in a multi-ethnic community sample. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(3):894–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casagrande SS, Gary TL, LaVeist TA, Gaskin DJ, Cooper LA. Perceived discrimination and adherence to medical care in a racially integrated community. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(3):389–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Houtven CH, Voils CI, Oddone EZet al. Perceived discrimination and reported delay of pharmacy prescriptions and medical tests. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):578–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shelton RC, Winkel G, Davis SNet al. Validation of the group-based medical mistrust scale among urban Black men. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):549–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aronson J, Steele CM. Stereotypes and the fragility of human competence, motivation, and self-concept. : Dweck C, Elliot E, Handbook of Competence and Motivation. New York, NY: Guilford; 2005:436–456 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Word CO, Zanna MP, Cooper J. The nonverbal mediation of self-fulfilling prophecies in interracial interaction. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1974;10(2):109–120 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pronin E, Steele CM, Ross L. Identity bifurcation in response to stereotype threat: women and mathematics. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2004;40(2):152–168 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burgess DJ, Powell AA, Griffin JM, Partin MR. Race and the validity of self-reported cancer screening behaviors: development of a conceptual model. Prev Med. 2009;48(2):99–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rauscher GH, Johnson TP, Cho YI, Walk JA. Accuracy of self-reported cancer screening histories: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(4):748–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJet al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 1999;282(6):583–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Major B, Kaiser CR, McCoy S. It’s not my fault: when and why attributions to prejudice protect self-esteem. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2003;29(6):772–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmader T, Johns M. Converging evidence that stereotype threat reduces working memory capacity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(3):440–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Office of Minority Health National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health Care, Final Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams DR, Jackson PB. Social sources of racial disparities in health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):325–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stone J, Moskowitz GB. Non-conscious bias in medical decision making: what can be done to reduce it? Med Educ. 2011;45(8):768–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Becker G, Newsom E. Socioeconomic status and dissatisfaction with health care among chronically ill African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):742–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Becker G, Gates RJ, Newsom E. Self-care among chronically ill African Americans: culture, health disparities, and health insurance status. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2066–2073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grady M, Edgar T. Racial disparities in healthcare: highlights from focus group findings. : Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparites in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003:392–405 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hatzfeld JJ, Cody-Connor C, Whitaker VB, Gaston-Johansson F. African-American perceptions of health disparities: a qualitative analysis. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2008;19(1):34–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gaston-Johansson F, Hill-Briggs F, Oguntomilade L, Bradley V, Mason P. Patient perspectives on disparities in healthcare from African-American, Asian, Hispanic, and Native American samples including a secondary analysis of the Institute of Medicine focus group data. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2007;18(2):43–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Logel C, Walton GM, Spencer SJ, Iserman EC, von Hippel W, Bell AE. Interacting with sexist men triggers social identity threat among female engineers. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;96(6):1089–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adams G, Garcia DM, Purdie-Vaughns V, Steele C. The detrimental effects of a suggestion of sexism in an instruction situation. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2006;42(5):602–615 [Google Scholar]

- 56.LaVeist TA. Racial segregation and longevity among African Americans: an individual-level analysis. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(6 pt 2):1719–1733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barr DA, Wanat SF. Listening to patients: cultural and linguistic barriers to health care access. Fam Med. 2005;37(3):199–204 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stein T, Frankel RM, Krupat E. Enhancing clinician communication skills in a large healthcare organization: a longitudinal case study. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;58(1):4–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Viggiano TR, Pawlina W, Lindor KD, Olsen KD, Cortese DA. Putting the needs of the patient first: Mayo Clinic’s core value, institutional culture, and professionalism covenant. Acad Med. 2007;82(11):1089–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marx DM, Ko SJ, Friedman RA. The “Obama effect”: how a salient role model reduces race-based performance differences. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2009;45(4):953–956 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marx DM, Goff PA. Clearing the air: the effect of experimenter race on target’s test performance and subjective experience. Br J Soc Psychol. 2005;44(pt 4):645–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McIntyre RB, Lord CG, Gresky DM, Ten Eyck LL, Jay Frye GD, Bond CF., Jr A social impact trend in the effects of role models on alleviating women’s mathematics stereotype threat. Cur Res Soc Psychol. 2005:10(9):116–136 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marx DM, Stapel DA, Muller D. We can do it: the interplay of construal orientation and social comparisons under threat. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88(3):432–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marx DM, Roman JS. Female role models: protecting women’s math test performance. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2002;28(9):1183–1193 [Google Scholar]

- 65.McIntyre RB, Paulson RM, Lord CG. Alleviating women’s mathematics stereotype threat through salience of group achievements. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2003;39(1):83–90 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Good JJ, Woodzicka JA, Wingfield LC. The effects of gender stereotypic and counter-stereotypic textbook images on science performance. J Soc Psychol. 2010;150(2):132–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Purdie-Vaughns V, Steele CM, Davies PG, Ditlmann R, Crosby JR. Social identity contingencies: how diversity cues signal threat or safety for African Americans in mainstream institutions. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;94(4):615–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Osborne JW. Testing stereotype threat: does anxiety explain race and sex differences in achievement? Contemp Educ Psychol. 2001;26(3):291–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spencer SJ, Steele CM, Quinn DM. Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1999;35:4–28 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee K, Kim H, Vohs KD. Stereotype threat in the marketplace: onsumer anxiety and purchase intentions. J Cons. Res. 2011;38(2):343–357 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ulrich RS, Zimring C, Barch XZet al. A review of the research literature on evidence-based healthcare design. HERD. 2008;1(3):61–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martens A, Johns M, Greenberg J, Schimel J. Combating stereotype threat: the effect of self-affirmation on women’s intellectual performance. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2006;42(2):236–243 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cohen GL, Garcia J, Purdie-Vaughns V, Apfel N, Brzustoski P. Recursive processes in self-affirmation: intervening to close the minority achievement gap. Science. 2009;324(5925):400–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cohen GL, Steele CM, Ross LD. The mentor’s dilemma: providing critical feedback across the racial divide. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1999;25(10):1302–1318 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brown JB, Stewart M, Ryan BL. Outcomes of patient-provider interaction. : Thompson TL, Miller KI, Parrott R, Handbook of Health Communication. London, UK: Earlbaum; 2003:141–163 [Google Scholar]