Abstract

Why are orphaned girls at particular risk of contracting HIV? Using a transition to adulthood framework, this paper uses qualitative data from Nyanza province, Kenya to explore pathways to HIV risk among orphaned and non-orphaned high school girls. I show how co-occurring processes such as residential transition out of the parental home, negotiating financial access and relationship transitions interact to produce disproportionate risk for orphan girls. I also explore the role of financial provision and parental love in modifying girls’ trajectories to risk. I propose a testable theoretical model based on the qualitative findings and suggest policy implications.

Keywords: Orphan girls, HIV/AIDS, transition to adulthood, Kenya

INTRODUCTION

The latest UNAIDS (2009) global report shows that sub-Saharan Africa continues to carry a disproportionate burden of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. An estimated 67% (22.4 million) of HIV/AIDS victims and 72% of AIDS deaths are in sub-Saharan Africa. Further, the statistics reveal striking gendered and generational health disparities. 59% of African HIV/AIDS victims are women and of these, 15-24 year old women experience rates which are two to nine times higher than those of their male counterparts (Laga et al 2001, UNAIDS 2005, UNAIDS 2008). When these statistics are coupled with the fact that almost every sub-Saharan African country has about 40% of their population under the age of 15 (PRB 2008), the emerging picture, in the absence of anti-retroviral treatment provides two motivating factors for this paper: first, that increasing numbers of these African youth are or will be transitioning to adulthood as single or double orphans; and second that orphaned female youth will be transitioning in a period in which they will face their highest risk for contracting HIV.

A growing body of quantitative evidence suggests that orphaned girls experience particular vulnerability to contracting HIV. Gregson et al (2005) using a population based cohort study in Manicaland, Zimbabwe, found that among orphans and vulnerable children (OVCs), 15-18 year old girls who were maternal orphans or had an HIV infected parent had significantly greater odds of having HIV infection compared to their non-OVC counterparts. In Harare, the capital city of Zimbabwe, Birdthistle et al’s (2008) random household based survey also found that female orphans had a higher prevalence of HIV and HSV-2 compared to non-orphans. Similarly Operario et al (2007) in a nationally representative household survey in South Africa found that 15-24 year old orphaned females experienced significantly greater odds of being HIV positive compared to females with both parents alive. The literature also suggests relative vulnerabilities in the proximate determinants of HIV (Boerma and Weir 2005). Thurman et al (2006), for example, in a Kwa-Zulu Natal survey found that among sexually active South African youth, orphans had earlier sexual debut than non-orphans. Palermo and Peterman (2009) using Demographic and Health Survey data found that among 15-17 yr old adolescent girls in Cote d’Ivoire, Lesotho, Mozambique and Tanzania, orphans experienced significantly higher odds of sexual debut compared to non-orphans. Operario et al (2007) found that female orphans had greater odds of reporting more than one sexual partner in the last 12 months compared to those with both parents living.

This paper builds on these quantitative findings by using data from a qualitative study among Kenyan high school girls to explore pathways that might produce disproportionate HIV risk for girls who are orphaned. Using a transition to adulthood framework, I examine how challenges associated with residential transition out of the parental home, combined with struggles to gain financial access to impact the kinds of relationships young women choose. I pay particular attention to the psychological dimension of transition, examining the role of lack of parental love in the choice of older partners with higher rates of HIV. The paper concludes with a hypothesized model that can be tested quantitatively to extend the findings of this study to other settings, as well as a discussion and policy implications section.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The Transition to Adulthood

The transition to adulthood framework, though in some ways peculiarly Western (Ruddick 2003), is a useful way of exploring the lives and developmental changes and challenges experienced by African youth (Mensch et al 1998; Lloyd 2005). It provides a lens through which to examine social processes and experiences salient to youth in the period between puberty and adulthood by examining key domains such as the pursuit of education, finding employment, attaining financial independence, relationship formation processes (culminating in marriage or a stable partnership), becoming a parent and residential transition (principally moving out of the parental home) (Hogan and Astone 1986, Shanahan 2000, Furstenberg 2000). In this paper, I will explore school girls’ experiences as they navigate residential, financial and relationship transitions to highlight the social dynamics that might produce disproportionate risk for girls who have lost one or both parents.

Demographic Density

A particular emphasis in this study is in understanding and operationalizing young people’s transition to adulthood as “demographically dense” (Rindfuss 1991:491). That is, as a period characterized by the multiple, simultaneous juggling of transition related decisions. Young people’s lives are characterized by the coinciding of multiple life changing events. Educational decisions impinge on residence; relationship decisions are sometimes intertwined with financial decisions and employment status. Thus rather than merely acknowledging such multiplicity and operationalizing the study in more discrete single transition ways (e.g. only examining relationship transitions and HIV risk, or educational transitions and HIV risk), I take demographic density as a starting point. Specifically, I will show how consequences of residential and financial transitions combine to create risky relationship transitions that potentially expose girls to HIV.

The Psychological Dimension to the Transition to Adulthood

The psychological context of young people’s transition to adulthood will be an important part of this analysis in light of studies among orphans finding that they have higher levels of anxiety, depression, anger and disruptive behavior compared to non-orphans (Foster et al 1997, Atwine et al 2005). These emotional issues might complicate transition related experiences of orphans. Perhaps the most salient and significant loss for adolescents when one or more of their parents die, is that of parental love. In a cross cultural study by McNeely and Barber (2010) on how parents make adolescents feel loved, adolescents were asked to list four things parents/caregivers did to make them feel loved. The authors find evidence for a typology of three kinds of supportive parenting. 1) Emotional support - “behaviors that communicate the adolescent is cared for and loved”; 2) Instrumental support - “practical and financial assistance”; and 3) Informational support - “guidance or advice geared toward solving a specific problem” (ibid, 605). I will argue in this paper that (perceived) lack of parental love, as indexed by these kinds of support, are consequential for the kinds of relationships school girls’ choose.

STUDY SETTING

Ethnographic interview based fieldwork was conducted in Nyanza Province in the western part of Kenya between December 2005-March 2006 and June - August 2006. Nyanza’s capital city, Kisumu is home to a bustling transportation hub, lying at the intersection of the Trans-African Highway (connecting the north, west and southern parts of Africa), as well as hosting ports on Lake Victoria shorelines linking to neighboring Uganda and Tanzania. Despite its role as a trading hub, many Nyanza inhabitants are poor. Absolute poverty rates (proportions of people living on less than $1 a day) ranged from 53% to 69% in District Development Plans from the study districts. Fieldwork was conducted in 4 districts in Nyanza province (Bondo, Nyando, Kisumu, and Homa Bay) selected for geographic diversity (north, middle and south Nyanza).

The Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS) 2004, a nationally representative survey which included HIV testing found that 18.3% of Nyanza women and 11.6% of Nyanza men were HIV positive, the highest provincial rates in the nation.1 These statistics are reflected in estimates of Nyanza’s burgeoning population of orphans. Using KDHS 1998 and US Bureau of the Census data, Bicego et al (2003:1240) estimated Kenya’s orphan population at 1,220,633 with 9.3% of Kenyan children under age 15 having experienced the loss of at least one parent, while 0.9% experienced loss of both parents (ibid 1237). By KDHS 2004, Mishra and Bignami-Van Assche (2008:87) estimated 1,529,288 orphans in Kenya, of whom 388,064 were located in Nyanza province. This represents about 25% of Kenya’s orphans.

School Based Orphans

Adolescent girls in high school represent a relatively small sample of female youth in Nyanza province. KDHS (2004) shows that while almost 100% aged 15-29 years began elementary school, only 28% in this age group reported at least some high school education. This reflects a high rate of attrition throughout the educational process. This is even more exacerbated among the orphan population. Case et al (2004), for example, in a 10 country DHS based study which included Kenya, showed that African orphans experience an educational disadvantage on the death of one or both parents and were less likely to be in school when household wealth was controlled. Particular challenges noted by Bennell (2005), Nyambedha et al (2003) and Kakooza and Kimuna (2005) were high absteentism from school both to care for sickly parents, as well as high demand for their labor at home, discipline problems at school resulting in their being sent home, as well as a limited ability of caregivers to pay school fees. As suggested by this literature, high attrition from school among orphans was also due to lack of school fees. This was evident in this setting as many orphans on losing their parents had also lost their best advocates for the pursuit of their education. Even if parents could not afford school fees, they could ask relatives to help them pay; however, with no parents, the orphans were dependent on remaining relatives agreeing to pool their resources to support them through high school.2 Thus the orphans interviewed in this study represent some of the most educated and advantaged Nyanza orphans.

This is nonetheless an important population to study because the burgeoning population of orphans in Nyanza suggested by the statistics cited above was not only acutely felt in the community, but also within schools. In the randomly selected schools visited, head teacher estimates of the rate of orphanhood ranged from ¼ to ¾ of students who were single or double orphans. These surprisingly high estimates reflect the fact that many schools were kept afloat by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) which sponsored orphans through school. In fact these NGOs were often more reliable fee payers than students who had living parents. As a result, while non-orphan students might drop out intermittently while parents were gathering funds for school fees, many sponsored orphans stayed in school because of continuous external donor support. For orphans sponsored by relatives, support was sustained by what many families caring for orphans saw as a symbolically important investment. To have educated somebody was seen as significant not only for the child but also in signifying the fulfillment of their duty to that child’s parent(s). As a result collective support by an extended family to pay for an orphan’s school fees, to the extent that they were committed, might have been easier than a poor parent asking relatives for help to support their child through school. The in-school orphan population are thus an important group to study especially as it allows us to see the extent to which going to school mitigates the immense challenge of parental loss during the transition to adulthood.

STUDY DATA and METHODS

This study was designed to explore youth transitions to adulthood in the context of an ongoing HIV/AIDS epidemic. It included 27 focus group interviews, 47 individual interviews, 20 key informant interviews including teachers, district and government officials, and community members, participant and non-participant observation and extensive field notes from interviews and ethnographic observations.3 Table 1 shows the classification of interviews.

Table 1.

Classification and Number of Interviews by Gender and Age Group

| WOMEN | MEN | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Interview | Focus Group Interviews | Individual Interviews | Focus Group Interviews | Individual Interviews |

| 15-19 years – in school | 9 | 7 | 3 | 2 |

| 20-29 – in school | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 15-29 years – out of school | 2 | 9 | 2 | 3 |

| 35 - 55 years | 4 | 8 | 2 | 5 |

| 56 years + | 1 | 6 | 2 | 5 |

| TOTAL | 17 | 31 | 10 | 16 |

The larger study provides the interpretational context for this paper which draws primarily on interviews conducted among 56 secondary (high) school girls from 10 schools.4 The schools were randomly selected from the Kenya Education Directory, a complete listing of all the schools in Kenya.5 Students were aged between 15-19yrs and were drawn from across all secondary school grades (Form 1(Grade 9) - Form 4 (Grade 12). Respondent selection was done by the principal or teacher in charge who were asked to select students randomly.6 A key limitation of the data is that students did not always self-identify their orphan/non-orphan status, as such, it is not possible to give a precise number of the orphans involved in the interviews.7 However, I clearly delineate in the interview excerpts below whether the respondent is an orphan or not.

I conducted school based interviews in English and/or Kiswahili, the national languages. Respondents were asked questions relating to youth transitions to adulthood; specifically, relationship formation -including dating and marriage, education, employment and financial access, in addition to whether they felt HIV/AIDS was a problem in their community. The salience of orphan status, residential transitions and the psychological dimensions to transitions to adulthood emerged in the course of interviews, ethnographic observations and data analysis. Along with 2 research assistants, I transcribed and where needed, translated all taped interviews. I subsequently conducted all coding and data analysis of interview transcripts and field notes. This was done through multiple readings of the material followed by thematic coding and organization of the material based on transition domains – residence, relationships, education, employment, money and financial access - as well as orphan status and parental love. Common themes within each of these areas were then identified and representative quotes of these drawn for this paper (Weiss 1994, Emerson et al 1995, Strauss and Corbin 1998).

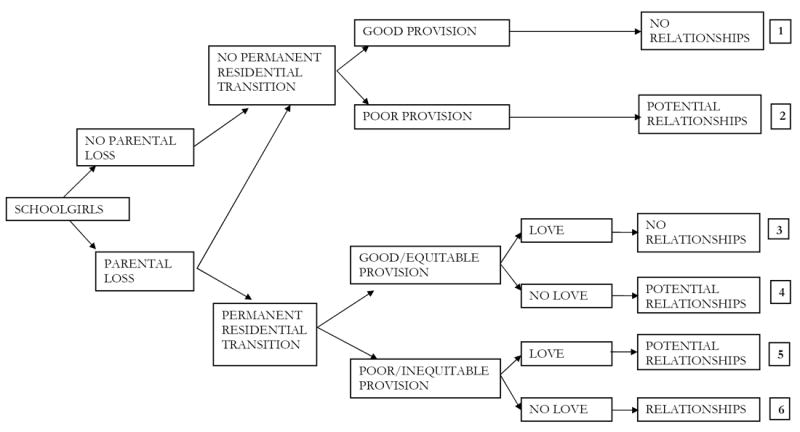

In the findings to follow, I will show the connections between residential transition out of the parental home, financial access and parental love among girls pursuing education and show the implications these have on relationship transitions and HIV risk. I conclude the results section by providing a hypothesized model (Figure 1) based on the findings, that can be tested quantitatively in future research.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Model

RESULTS

Residential Transition out of Parental Home

Residential transition was a reality for many school girls regardless of orphan status, as many Kenyan schools are boarding schools requiring students to stay at the school for most of the year with returns to the parental home during holidays. In some cases, school girls also moved to stay with a relative such as an aunt or grandmother who lived near their desired school to save money on commuting and boarding fees.8 However, what was consequential for school girls who became orphans was a shift in what they considered “home.” For some orphans, residential transition out of the parental household following a death was the beginning of not one, but multiple transitions across guardians’ households (see also Nyambedha 2007). Regardless of whether “succession planning” had been undertaken by parents to decide where their children should go on their death (Freeman and Nkomo 2006), interviews in this context revealed that this was rarely a decision shared with their children. It was often experienced as a period of uncertainty and girls felt at the mercy of their relatives. Guardians most often mentioned in interviews were grandparents, their parents’ siblings, or their own older siblings. In a focus group interview, for example, one girl described the process:

“Let’s say when your parents pass away and the relatives are there, then it’s upon them to choose who to stay with.” (15-19yr old, orphan school girl)

Another noted,

“Somebody will be like I am going to take so and so, I want to stay with so and so, then it’s upon them to choose. Then you have to go.” (15-19yr old, orphan school girl)

Orphan girls described scenarios where they were relatively powerless in the decision of where they would ultimately end up. A major consequence of this decision making was the scattering of siblings among several different relatives who did not always live in the same locale, and who they were not always able to see often. For example, a paternal orphan school girl in another setting described what happened to her and her eight unmarried siblings after her father died:

“Due to the death of my father, we are really separated. My mother is staying with my two brothers and one sister at home. My other sister, [a] married sister is staying with one son there, and another one is staying with two and here we are two, another one is in [boarding] school.” (15-19yr old, orphan school girl)

In this way, many orphans’ traumatic loss of a parent was compounded by isolation and separation from those closest to them at precisely the time they needed them most. These circumstances were in stark contrast to non-orphan girls for whom the move was decided in conjunction with parents and who often returned home to parents and siblings during school holidays.

Transitions between households also often coincided with a shift from an urban to a rural setting. Unlike some non-orphans in the study whose move to a rural area would only be during the school year, and who returned to the city for holidays, for orphans this shift was experienced as permanent. This sometimes meant dramatic changes in lifestyle and expectations. A non-orphan school girl, whose parents lived in the city while she stayed with her grandmother in a rural setting to go to school, described the plight of her orphaned best friend.

“Her dad died. [He] used to work but the mom do nothing. So immediately when the dad died, they were [living] in Coast, so they had to come back home [to rural Nyanza]. So the life, you know the life changes as you continue staying in the rural area. So she had to change.” (15-19yr old, school girl)

Many Nyanza men migrated outside the province for work, and the Coast Province, where the second largest city in the country is located, was a major destination for them. The move that this girl was experiencing, then, was to a remote rural area where this particular school was located. The girl was a paternal orphan, but even though her mother was still alive, her lifestyle as she shifted from an urban to rural setting had radically changed. While in the city there would be running water, electricity, and supermarkets to buy packaged groceries, in the rural area a girl would be more heavily involved in tiring domestic work, especially during school holidays. In this location, girls would go to a far away river to collect water and go to the hills to collect firewood for cooking. Her non-orphaned friend, however, experienced school holidays as a relief on return to the city.

For many teenage school girls in the study, moving to a guardian’s household as an orphan was often, they felt, construed as an arrival of a domestic helper who also happened to be going to school. As one girl, described,

“Like me I am an orphan. I have been staying with my uncle for eight years. Ai, [exasperated sigh], staying with them…the type of work you are doing, it is huge because if, even if they are having the kids, you are the one who will be given large portions to be doing but the lighter portion will be given to the others.” (15-19yr old, orphan school girl

As the above excerpt illustrates, after school housework allocation was a major source of ill feeling among orphan girls – both in terms of the amount and the perceived inequity of expectations between them and the natal non-orphan children. As one orphan noted,

“Some [natal children] even say that it is their father who is providing for your school fees so there is no need of them working and you are there.” (15-19yr old, orphan school girl)

I asked one orphan girl, to describe a typical evening between 5pm when she got home from school and 11pm when she said she slept.

“Okay, you know from school you go, then you go buy the supper all the way from the market and you come back and prepare the supper for the family. Okay supper can take like, let’s say it’s a big family, so like one and a half hours. Meaning by 8.30pm the supper is ready, they are eating. They are through with supper, you clean the tables, then arrange them well, then you mop the house. Then you boil water for everybody to bathe. [Many settings do not have running hot water]. Okay, so let’s say it’s a family of eight, you have to boil water for the eight of them and including yourself maybe. Then that is through, let’s say you had washed some clothes in the morning, you want to iron them, then the children’s clothes, they are going to school tomorrow, you wash them. You see.” (15-19yr old, orphan school girl)

While for a few orphans, housework was shared among all the children, the quote above represents a typical experience reported by many other orphan girls I asked. Those going to boarding/residential secondary schools described this as their experience when they returned to guardian households during holidays. Thus while all school girls did housework, the difference between orphans and non-orphans was orphans’ sense of unfairness in division of labor in their place of residence.

Financial Access and Resource Provision

This sense of inequity was also experienced in financial access and resource provision in the new household. While these two issues were important for all school girls interviewed, orphan girls often made two kinds of comparisons in their assessment. They compared their financial access when they were non-orphans to their current financial access as orphans; and they compared their current access to that of non-orphan children with whom they shared a household. Whether school going orphans moved to a financially able or poorer household than their original residence, their status as orphans as opposed to natal children meant that they could no longer assume that a request for money to buy something they wanted would be forthcoming.

The following excerpt is from an individual interview with a paternal orphan girl who describes the difference between life when her father was alive, and life in her new guardian’s household when it came to financial provision.

I: And so what do you think has been the hardest part of growing up for you?

R: The hardest part for me is when I want to ask for money. …that guardian that I am staying with, won’t agree with anything I want to ask and now, she is going ahead and telling all of the family members that I am [a] disturbance.

......

I: So how was life different when your father was still alive?

R: When my father was still alive, actually there we were feeling very comfortable. There was no kid of us who was living with the sister or with the relative, no. We were just living together. If you want something, you will ask for it. Even your mother will provide for you. Because my mother was working and my father was also a businessman. Now, they [would] just provide for you easily.

(15-19 yr old orphan school girl)

For this girl, and many other orphan girls, the contrast between life with parents and life with guardians became especially salient when they came from a home where they felt they were well provided for and moved to a home where they felt asking for money and resources was a struggle. As this was a population of relatively advantaged orphans – given that they were going to school – few orphans discussed being in poor households where they felt their guardians were simply not able to afford the things they were asking for.

Orphan girls also often noted the perceived unfairness in the distribution of resources in guardian households; they felt that what they got was less than that of natal children. In a typical description of this inequity, when asked whether they felt they were treated differently by their guardians or as part of the family, a focus group of orphans said differently with one elaborating,

“Mostly when it comes to the shopping for going back to school. You find that let me say, the guardian is also having some children who are in boarding school, and you’re also in the boarding school. So if this mother is given the money for the shopping, she just goes there and does the shopping very well, but coming with the things she gives most of the things to her children and just a few will be given unto you. So it’s really not fair.” (15-19yr old, orphan school girl)

The Psychological Dimension: Parental Love

Girls with living parents did not mention parental love in interviews. However girls who had lost their parents often said one of the things they were looking for in their new home was what they called “parental love.” The clearest elaboration of this emerged in a focus group interview composed of orphans.

I: What do you miss most about living in your own home, with your own parents?

R1: Love

R2: Parental love.

Later in the interview, one girl explained,

“To me I think that when it comes to parental love I thought that they [my guardians] were going to show parental love because by that time they know that you are an orphan and you want somebody to love you.” (15-19yr old, orphan school girl)

In trying to elaborate what orphans meant by parental love, I asked the focus group what parental love looked like or involved, and a girl responded,

“You know if you have your parents, okay they look concerned. Concerned about everything like when you are sick, you’re lacking something or anything, like if you report that to them, it won’t take that much time for them to perhaps provide for you whatever it is. But when you stay with somebody you have to tell him or her just one thing it takes you three weeks, just reminding them. So they are less concerned.” (15-19yr old, orphan school girl)

The overall sense from interviews was that girls marked the presence of parental love by “concern” (care, emotional support, discipline and guidance and counseling), equity in treatment between them and natal children (who offered a contrast), and financial/resource provision. This closely matches McNeely and Barber’s (2010) typology cited earlier. Thus perceived lack of love was evidenced by inequities in division of labor for household chores, expressions of concern and financial provision between them and natal children in guardian households, or between what they experienced in their parental homes and what they experienced in their guardian households. This lack of perceived love – as marked by financial provision and concern – I will argue, contributed to the relationship choices that girls made, with consequences for their HIV risk.

Relationship Transitions and HIV Risk

The most risky relationships for girls in this, and other settings across sub-Saharan Africa, are relationships with older partners. In Nyanza province, my own analysis of KDHS (2004) suggests that 15-19 yr old adolescents would be at almost no risk of HIV acquisition if they partnered with a young man the same age as themselves. However, the likelihood of encountering an HIV positive partner increases substantially with men in older age groups. Unfortunately, interviews in this study suggested that older men were precisely the sorts of men that girls, and orphan girls in particular, picked.9 As one orphan girl noted,

“when you came from a very supportive family, your dad used to give you everything you need, your mom. Then it comes to a situation whereby maybe you have to beg somebody for it or maybe you just have to work hard for it. So most of us do fall victims especially of those working men.” (15-19yr old, orphan school girl)

Girls described these men as “working men” or “working class men” (in contrast to unemployed or school boy boyfriends) – slightly older boyfriends who were employed. Interviews suggested that partner choice was less about age of partners, than it was about their employment status and consequent access to income. As such, they could be men in their early twenties, as opposed to sugar daddies (10 or more years older), though the latter were also mentioned in interviews. (See also Luke 2003; Chatterji et al 2004; Longfield et al 2004; and Swidler and Watkins 2007). Partners included fishermen, men from construction crews building roads through various communities, local businessmen (some of whom sponsored young women through school), and migrant workers who came home to visit their families periodically.

In this next section, I will show how while relationships with older partners were chosen by school girls regardless of orphan status, the motivations for such relationships differed. I will argue that for non-orphans, girls from poorer households were the most susceptible to relationships with older men for mainly material reasons, while for orphans, such relationships were motivated by both material and emotional lack.

Why girls chose older partners

Non-orphan girls most commonly associated with relationships with older men in the data were those with poor parents. Some girls faced with financial lack reported that they would just “go without” if there was something they wanted that their parents could not provide. However, for others, parental poverty, and in some cases, parents’ approval, was often noted as a justification for non-orphans risky relationship choices. In one focus group, for example, after girls’ discussion of transactional relationships with fishermen – the predominant “working boyfriends” in this community - I asked whether parents were aware of these relationships. They responded,

R1: Yeah, even in the case where you have both parents, let’s say that they are alive, both of them but they doesn’t have any work which they can do in order to provide your needs. So they will not even bother you a lot because so long as you can provide those things by yourself, you will not come to them asking them for them. So they can just leave you anyhow to go and look for them.

I: So you think part of the problem is parents don’t have enough money to support the children?

R2: But now madam, some parents do encourage this issue. Let’s take a house where all the parents are poor, you know even a mother can go and tell her girl, you just go and have even a boyfriend so whenever he gives you something, you come back to the house and we share. That is the case.

(15-19 yr old school girls)

Approval by parents and community members of these relationships came up in several interviews (see also Bledsoe 1990). Given that these were girls in school, for many girls, what counted as “needs” or “necessities” when I asked them, were rarely basic provisions such as food, but rather items such as sanitary pads, new or secondhand clothing and shoes, cosmetics and toiletries. Girls and teachers noted that parents and guardians did not consider sanitary pads as a “need” and therefore did not feel obligated to provide them.

For girls with parents, parents could serve as a counterpoint to these relationships as the following excerpt from a non-orphan school girl illustrated. When asking a focus group of school girls if they had partners, one noted,

R: Me I had someone but nowadays I left him.

I: What happened?

R: I saw that I was not gaining anything on him so I just dropped him…

I: So you weren’t gaining anything, how do you mean? He wasn’t helping or he wasn’t giving you anything?

R: He was just giving me something but I just see that there is no need of it because my parents are still alive and I can, they can really give me those things.

(15-19 yr old school girl)

Orphan girls were drawn to older partners not just because of material lack, but also because of provision of concern. An HIV positive orphan I interviewed in a focus group interview among out of school youth, for example explained about her older partner,

I just loved him because he was just paying for me school fees and helping me.

(15-29 yr old orphan)

Indeed, orphan girls would often provide a lack of financial support, resource provision or concern as rationales for turning to older partners, as the following two excerpts from different interviews illustrate.

“So you can see that even in our homes you can find a girl when she has lost all her parents so now she wants a way in which she can live. So the only alternative which she can see is just to go and find even a boyfriend who can provide the necessities which she can go in her life.” (15-19yr old, school girl)

“I had a friend of mine. Her parents passed away and she was only one in the family… She had to go and stay with an aunt who also comes from around here. Then the aunt was just less concerned about her, not providing anything, you’re just seeing her there. Then she happened to become a victim of a certain man who was working. Then the man promised the girl to take her back to school. She was in Form 2. Then I don’t know what happened, but the man dumped her after impregnating the girl. Now she had to give birth. Then the family complained that she is being immoral, something like that. But she is not going to school nowadays. She is just staying there, with her child there.” (15-19 yr old, double orphan school girl)

As these two excerpts highlight, lack of provision of necessities in the first case, and lack of concern and provision in the second case, were reasons orphans gave in these and other interviews for relationships with older partners. In a few interviews, scenarios like the one above or situations where there was no money for school fees, or alternative/willing care givers for younger siblings resulted in the end of school for girls, and subsequent early marriage, itself a risk factor for HIV (Clark 2004).

In sum, parental loss was associated with transition related circumstances that set orphan girls on a particularly vulnerable path to HIV risk. Involuntary residential transition out of the parental home placed them in households where they felt particularly exposed to inequities in household labor, financial and resource provision, and parental love. The combination of these circumstances contributed to dangerous relationship transitions, the selection of partners who might place them at higher risk of HIV. In this, I am arguing against a more narrow conception of transactional relationships with older men linked to the pursuit of material needs, and suggesting that for orphans, the material provision in these relationships also marked a concern that they felt they lacked in their guardian households. For non-orphans, relationships seemed mainly driven by poor financial or resource provision by parents, as well as parents’ approval of partnerships with providing older partners.

Hypothesized Model

In order to see if these results are applicable to other settings across sub-Saharan Africa, I conclude this section by providing a model based on the results of this study, that can be tested quantitatively in future research. In Figure 1, I show hypothesized pathways to risky relationships among orphaned and non-orphan school girls. The three main hypotheses illustrated in the 6 pathways in Figure 1 are:

Hypothesis 1: Girls who feel well (or equitably) provided for and loved in their household are the least likely to engage in relationships with older partners (Pathways 1 and 3)

Hypothesis 2: Girls who feel poorly (and/or inequitably) provided for or do not feel loved in their household are likely to have relationships with older partners (Pathways 2, 4, 5)

Hypothesis 3: Girls who feel poorly (and/or inequitably) provided for and do not feel loved in their household are the most likely to have relationships with older partners (Pathway 6)

The figure shows pathways to risk for school girls based on whether or not they lose a parent, and whether or not they experience (permanent) residential transition out of the parental home. Two key assumptions need to be made here based on findings. First, for non-orphans, I assume that the transition to different households would not put them in a similar trajectory as orphans because their residential transition is not experienced as permanent. (i.e. they have living parents who can theoretically provide love and resources from afar, and they have a home to which they can theoretically return). Second, for orphans, I assume that the difference in whether they follow non-orphans’ pathways or not is whether the shift is experienced as permanent (no possibility of returning to a parental home). I assume that for orphans who only lose one parent and move, because they still have someone who can provide parental love and resources from afar, their pathways will be similar to non-orphans. However, orphans who lose a parent and have a dying parent being taken care of elsewhere, and thus do not have the possibility of returning to a parental home, will have similar pathways to orphans who have lost both parents.

For the first hypothesis, pathway 1 delineates school girls (non-orphans and single orphans) who feel well provided for, while pathway 3 delineates orphans who feel well/equitably provided for and loved. The hypothesis thus assumes that the effects of orphanhood on the likelihood of engaging in relationships with older partners can be mitigated by good/equitable provision and a sense of parental love in the new residence. As noted in the findings, the topic of parental love did not emerge in interviews with non-orphan girls. However, what appeared consequential for relationships with older partners was whether parents were poor or not and this is reflected in the model. For the second hypothesis, pathway 2 delineates school girls (non-orphans and single orphans) who feel poorly provided for, pathway 4 delineates orphans who feel well/equitably provided for, but not loved, while pathway 5 delineates orphans who feel poorly/inequitably provided for but loved. Finally, for the third hypothesis, pathway 6 delineates orphans who feel poorly/inequitably provided for and not loved.

In addition to questions that are standard on surveys on sexual behavior and STI/HIV status, testing this model quantitatively would require a survey that included questions on:

Whether an adolescent felt well provided for materially or not (it would be useful here to distinguish between basic provision – food, shelter etc, and “wants”)

Whether an orphan in a new home felt the distribution of resources was equitable among the children in the home

Whether an orphan in a new home felt loved.

PAPER LIMITATIONS

This study was based on a small sample of school girls and orphans in a high HIV prevalence setting, and as such may have limited generalizability in other settings in Kenya and across the continent. The provision of a testable model is designed to extend the applicability of this study to other settings with larger samples of adolescents. Additionally, the study was not explicitly set up to study orphans. Rather, the salience of orphans emerged in the course of ethnographic fieldwork, interviewing and data analysis.

The paper marks whether quotes are from self-identified orphans and draws on excerpts that explicitly referred to orphans. However, not designing the study to focus on orphans affected both the depth of questions asked of and about orphans during interviews, and is also reflected in the lack of systematic accounting of the number of orphans in each interview. Finally, my own status as an outsider, and the widespread nature of NGOs, NGO personnel and external donors in this setting, may also have meant that orphans exaggerated the extent of the challenges and inequities they felt in their settings. However, many of the key findings highlighted in the study were present even in interviews among the most distressed and heartfelt interviews conducted in the study, where the authenticity of orphans’ feelings was clear.

DISCUSSION

Understanding the transition to adulthood as a demographically dense life period provides a more complete context for exploring adolescent girls’ pathways to HIV risk. In this case, this risk was characterized as a product of interactions between residential transition out of the parental home, financial access and relationship transitions. By contrasting orphans with non-orphan girls, I showed how for orphan girls, juggling these transitions often produced a combination of psychological and financial challenges. Relationships with epidemiologically risky partners – with their emotional and material support – provided relief but also embedded orphan girls in a complex web of dependence on these types of relationships. Unfortunately, this might contribute to orphan girls prolonged engagement in relationships with riskier partners, increasing their likelihood of contracting HIV.

These findings were particularly striking to observe among a unique population of orphan girls who were able to remain in secondary school through NGO, donor or family support – girls whom one would expect to be relatively protected from risky sexual partnerships. However they highlight how circumstances can combine to undermine the advantages education might otherwise provide. It also elucidates why in some quantitative studies, orphan status remained significant in predicting earlier sexual onset than non-orphans even when poverty and school enrollment were controlled (Thurman et al 2006:632). The widespread and almost normative nature of transactional relationships with men with money across sub-Saharan Africa, suggests that similar risk might also exist among girls in other African settings who face the same combination of parental loss, residential change and a decline in financial status or access while pursuing education. The model proposed in Figure 1 would be a useful way of testing this.

The study also showed that among non-orphan school girls, relationships with older partners were attractive for primarily material reasons, and were sometimes supported by family and community members. However, the fact that their psychological needs were likely not as acute as that of orphaned girls, suggests that they are both less susceptible to entering into these relationships compared to orphaned girls, and might more readily exit them thus limiting their exposure to risk.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The study findings suggest that while financial and material provision (particularly of sanitary pads), might be sufficient for non-orphan girls with poor parents, policy initiatives which focus exclusively on educational or material provision for orphan girls might not be sufficient to reduce the attractiveness of relationships with older men. Emotional and psychological provision should be part of a comprehensive HIV prevention strategy.

Dealing with the emotional and psychological precedents, for example, might mean making individual and group counseling on grief and loss an explicit and critical part of HIV/AIDS prevention programs. In addition, using funds to facilitate sibling visits to help the grieving process might mitigate the search for love from older partners. Similarly, including discussions about orphans perceived inequity and need for parental love in community forums and discussions on orphan care, and facilitating group exchanges between orphans and adults who act as guardians might also be useful. Even while guardians of many orphan girls might be educating and supporting these young women the best way they know under economically strained conditions, the perception the girls have is what is ultimately consequential in motivating their subsequent actions. Facilitation by external agents might enable conversations that might otherwise not occur in communities and cultures where female youth in households do not always have a voice. Finally, educating adolescent girls about the ultimate costs of relationships with older partners in terms of contracting HIV/AIDS might change the calculus in their minds about whether to enter into these relationships (see for example Duflo et al 2006 and Dupas 2006). All these strategies would engage directly with outcomes from multiple transition events in adolescent girls’ lives that might otherwise lead to their seeing risky relationships as viable solutions to their challenges.

Acknowledgments

I thank Linda Waite, Shelley Clark and the Population Reference Bureau for primary funding of this research as well as the Henderson Dissertation Fellowship which supported the early writing stages of the material used in this paper. I thank the SFP anonymous reviewers and Annie Dude for comments on earlier versions of this paper. I also thank Richard Jessor for helpful suggestions and encouragement.

Footnotes

In KDHS (2010), the HIV rates among Nyanza province women and men were 16% and 11.4% respectively. I use the 2004 statistics because they are closer to the time fieldwork was conducted (2005-2006).

At the time of the interviews, high school was not free or subsidized in Kenya. The current regime of subsidized high school education may have resulted in more orphans in school.

Ethical considerations: The project was approved by the University of Chicago institutional review board, the Ministry of Education, Republic of Kenya, and all relevant Nyanza district and school officials. Verbal informed consent for interviews and taping of interviews (where they were taped) was sought from all respondents before any interviews were begun. In addition, for respondents in institutions, administrators provided written informed consent in loco parentis. For community interviews, verbal informed consent was also provided by the surviving parent or guardians of all participants aged below age 18. Both before and after the interview, respondents also had ample opportunity to ask questions about the interview or other topics of interest to them.

As Table 1 shows, 9 focus groups and 7 individual interviews were conducted among 15-19yr old girls in school. A focus group interview was conducted in 9 schools. Each group was composed of 6 girls, making for a total of 54 respondents. In 5 of the 9 schools, an individual interviewee was drawn from each focus group after the group discussion had ended. Drawing individual interviewees from focus groups not only allowed trust to be built up with the respondent during the focus group interview, but also facilitated follow up in greater depth of what was said during the focus group interview. In the 10th school, only 2 individual interviews were conducted (no focus group). These two girls in addition to the 54 from the 9 other schools make up the 56 school girls interviewed for this paper. While these interviewees form the primary basis for this paper, I also use an interview excerpt from 1 out of school community based focus group interview among female youth ranging in age from 15 to 29. The youth were recruited from a community near one of the randomly selected schools.

In the Kenya Education Directory, Nyanza province had 579 public schools in total. Nyanza province has 1 national school which was not part of this study. At the provincial/district level, in the 4 districts of study, Bondo had 32 schools, Nyando 41 schools, Homa Bay 17 schools and Kisumu 47 schools. For each district, schools were numbered, numbers placed in a hat, and numbers representing a school were drawn randomly.

I asked teachers for a random selection of students, but teachers’ interpretation varied widely across schools. Some picked students who happened to be near the school office at the time, others picked students who had a free class period, others asked for volunteers, some picked students who they felt would be talkative, and some teachers’ only selected orphans for the study. In only one instance did a teacher ask for volunteers, put the volunteers’ names in a hat and randomly select 6 students for interview.

2 focus group interviews were composed exclusively of orphans (12 students), while the remaining 7 were composed of a mixture of orphans and non-orphans. The data do not allow for a precise count of the numbers of orphans in the mixed groups.

Several students also said that their urban parents felt that it was better to send their daughters to rural schools to separate them from the influence of the city, and because they felt discipline was better in rural areas.

While relationships with older partners can often be interpreted as coercive and characterized by an imbalance in power and authority, many girls in this study reported relationships as voluntary. Luke’s (2003) review of age and economic asymmetric partnerships supports this, suggesting that while many young African women can choose entry and exit of relationships with older partners, they have less power over the content of those relationships, e.g. negotiating safe sex.

References

- Atwine Benjamin, Cantor-Graae E, Bajunirwe F. Psychological Distress among AIDS orphans in rural Uganda. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul Bennell. The Impact of the AIDS Epidemic on the Schooling of Orphans and Other Directly Affected Children in sub-Saharan Africa. The Journal of Development Studies. 2005;41(3):467–488. [Google Scholar]

- Bicego George, Rutstein Shea, Johnson Kiersten. Dimensions of the emerging orphan crisis in sub-Saharan Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;56:1235–1247. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birdthistle Isolde J, Floyd Sian, Machingura Auxillia, Mudziwapasi Netsai, Gregson Simon, Glynn Judith R. From affected to infected? Orphanhood and HIV risk among female adolescents in urban Zimbabwe. AIDS. 2008;22:759–766. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f4cac7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bledsoe Caroline. School Fees and the Marriage Process for Mende Girls in Sierra Leone. In: Sanday Peggy Reeves, Goodenough Ruth Gallagher., editors. Beyond the Second Sex: New Directions in the Anthropology of Gender. Ch 10. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1990. pp. 283–309. [Google Scholar]

- Boerma J Ties, Weir Sharon S. Integrating Demographic and Epidemiological Approaches to Research on HIV/AIDS: The Proximate-Determinants Framework. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S61–7. doi: 10.1086/425282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anne Case, Christina Paxson, Joseph Ableidinger. Orphans in Africa: Parental Death, Poverty and School Enrollment. Demography. 2004;41(3):483–508. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterji Minki, Murray Nancy, London David, Anglewicz Philip. The Factors Influencing Transactional Sex Among Young Men and Women in 12 Sub-Saharan African Countries. USAID: The Policy Project. 2004 doi: 10.1080/19485565.2002.9989099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Shelley. Early Marriage and HIV risks in sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning. 2004;35(3):149–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2004.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duflo Esther, Dupas Pascaline, Kremer Michael, Sinei Samuel. Education and HIV/AIDS Prevention: Evidence from a randomized evaluation in Western Kenya. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4024. 2006 Oct; [Google Scholar]

- Dupas Pascaline. Relative Risks and the Market for Sex: Teenagers, Sugar Daddies and HIV in Kenya. 2006 Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson Robert M, Fretz Rachel I, Shaw Linda L. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Foster G, Makufa C, Drew R, Mashumba S, Kambeu S. Perceptions of children and community members concerning the circumstances of orphans in rural Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 1997;9(4):391–406. doi: 10.1080/713613166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M, Nkomo N. Guardianship of orphans and vulnerable children. A survey of current and prospective South African caregivers. AIDS Care. 2006;18(4):302–310. doi: 10.1080/09540120500359009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg Frank F. The Sociology of Adolescence and Youth in the 1990s: A Critical Commentary. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:896–910. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Garnett GP, Wambe M, Lewis JJC, Mason PR, Chandiwana SK, Anderson RM. HIV infection and reproductive health in teenage women orphaned and made vulnerably by AIDS in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 2005;17(7):785–794. doi: 10.1080/09540120500258029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan Dennis P, Nan Marie Astone. The Transition to Adulthood. Annual Review of Sociology. 1986;12:109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kakooza James, Kimuna Sitawa R. HIV/ AIDS Orphans’ Education in Uganda: The Changing Role of Older People. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships. 2005;3(4):63–81. [Google Scholar]

- KDHS (2004) Central Bureau of Statistics CBS [Kenya] Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2003. Calverton, Maryland: CBS, MOH and ORC Macro; 2004. Ministry of Health (MOH) [Kenya] and ORC Macro. [Google Scholar]

- KDHS (2010) Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) and ICF Macro. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008-9. Calverton, Maryland: KNBS and ICF Macro; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Laga Marie, Schwärtlander Bernhard, Pisani Elisabeth, Sow Papa Salif, Caraël Michel. To stem HIV in Africa, prevent transmission to young women. AIDS 2001. 2001;15:931–934. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200105040-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd Cynthia B. Growing Up Global: The Changing Transitions to Adulthood in Developing Countries. Panel on Transitions to Adulthood in Developing Countries. In: Lloyd Cynthia B., editor. Committee on Population and Board on Children, Youth, and Families Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academics Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Longfield Kim, Glick Anne, Waithaka Margaret, Berman John. Relationships Between Older Men and Younger Women: Implications for STIs/HIV in Kenya. Studies in Family Planning. 2004;35(2):125–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2004.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nancy Luke. Age and Economic Asymmetries in the Sexual Relationships of Adolescent Girls in Sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning. 2003;34(2):67–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2003.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely Clea A, Barber Brian K. How do Parents Make Adolescents Feel Loved? Perspectives on Supportive Parenting From Adolescents in 12 Cultures. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2010;25(4):601–631. [Google Scholar]

- Mensch Barbara S, Judith Bruce, Margaret E Greene. The Uncharted Passage: Girls’ Adolescence in the Developing World. New York: Population Council; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vinod Mishra, Simona Bignami-Van Assche. Orphans and Vulnerable Children in High HIV-Prevalence Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. DHS Analytical Studies No.15 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Nyambedha Erick Otieno, Wandibba Simiyu, Aagaard-Hansen Jens. Changing patterns of orphan care due to the HIV epidemic in western Kenya. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57:301–311. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyambedha Erick Otieno. Vulnerability to HIV infection among Luo female adolescent orphans in Western Kenya. African Journal of AIDS research. 2007;6(3):287–295. doi: 10.2989/16085900709490424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleke Christopher, Blystad Astrid, Rekdal Ole Bjørn. When the obvious brother is not there”: Political and cultural contexts of the orphan challenge in northern Uganda. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:2628–2638. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Operario Don, Pettifor Audrey, Cluver Lucie, MacPhail Catherine, Rees Helen. Prevalence of Parental Death Among Young People in South Africa and Risk for HIV Infection. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2007;44(1):93–98. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243126.75153.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo Tia, Peterman Amber. Are Female Orphans at Risk for Early Marriage, Early Sexual Debut, and Teen Pregnancy? Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning. 2009;40(2):101–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2009.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Population Reference Bureau. World Population data sheet of the Population Reference Bureau. 2008 ( www.prb.org)

- Rindfuss Ronald R. The Young Adult Years: Diversity, Structural Change, and Fertility. Demography. 1991;28(4):493–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruddick Sue. The Politics of Aging: Globalization and the Restructuring of Youth and Childhood. Antipode. 2003;35(2):334–362. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan Michael J. Pathways to Adulthood in Changing Societies: variability and Mechanisms in Life Course Perspective. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:667–692. [Google Scholar]

- Anselm Strauss, Juliet Corbin. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Second Edition. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Swidler Ann, Watkins Susan Cotts. Ties of Dependence: AIDS and Transactional Sex in Rural Malawi. Studies in Family Planning. 2007;38(3):147–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2007.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurman Tonya R, Brown Lisanne, Richter Linda, Maharaj Pranitha, Magnani Robert. Sexual Risk Behavior among South African Adolescents: Is Orphan Status a Factor? AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10:627–635. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS (2005) AIDS epidemic update. 2005 Dec; [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS (2008) AIDS epidemic update. 2008 Dec; [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS (2009) AIDS epidemic update. 2009 Dec; [Google Scholar]

- Weiss Robert S. Learning From Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies. New York: The Free Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]