Abstract

Significance: Since their discovery in the early 1990's, S-nitrosylated proteins have been increasingly recognized as important determinants of many biochemical processes. Specifically, S-nitrosothiols in the cardiovascular system exert many actions, including promoting vasodilation, inhibiting platelet aggregation, and regulating Ca2+ channel function that influences myocyte contractility and electrophysiologic stability. Recent Advances: Contemporary developments in liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry methods, the development of biotin- and His-tag switch assays, and the availability of cyanide dye-labeling for S-nitrosothiol detection in vitro have increased significantly the identification of a number of cardiovascular protein targets of S-nitrosylation in vivo. Critical Issues: Recent analyses using modern S-nitrosothiol detection techniques have revealed the mechanistic significance of S-nitrosylation to the pathophysiology of numerous cardiovascular diseases, including essential hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, ischemic heart disease, stroke, and congestive heart failure, among others. Future Directions: Despite enhanced insight into S-nitrosothiol biochemistry, translating these advances into beneficial pharmacotherapies for patients with cardiovascular diseases remains a primary as-yet unmet goal for investigators within the field. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 270–287.

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO•) is a ubiquitous molecule that participates in a versatile range of key biological functions. As a small gaseous, lipophilic nitrogen oxide, the biochemistry of NO• affords diffusion-limited, rapid penetration of the mammalian cell membrane, whereupon it may interact with various target molecules to induce a wide range of biological effects. In blood vessels, for example, protein kinase G (PKG)-dependent vascular smooth muscle cell relaxation and inhibition of platelet aggregation are induced by NO• via activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC), which converts guanosine triphosphate (GTP) to cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), the key cofactor for PKG. Although abnormal NO•-cGMP signaling is well established as a pathobiological mechanism in the development of many human cardiovascular diseases, cGMP-independent post-translational modification(s) of proteins by NO• has emerged as an important process involved in the regulation of cardiovascular function.

It has long been recognized that a significant discrepancy exists between the half-life of pure NO• in an aqueous solution and that observed for NO• in vivo (0.1 vs. 6 s) (49). This observation raised speculation regarding the formation of NO•-harboring molecular adducts, proposed conceptually as a mechanism to protect NO• from inactivation, thereby accounting for differences in the half-life. Owing to the reactivity of organosulfurs and the abundance of reduced thiols in plasma, S-nitrosothiols evolved as a potential candidate pool of NO• adducts. In support of this hypothesis was the seminal observation that under certain experimental conditions S-nitrosylation of the nucleophilic sulfur can occur (128). Moreover, such S-nitrosothiols were found to be functional, capable of promoting vasodilation and inhibiting platelet aggregation (70, 128).

Over the ensuing two decades, advances in mass spectrometry and the development of biotin- and His-tag switch assays have overcome many early procedural and biochemical limitations preventing the ready detection of post-translationally modified S-nitrosylated proteins. This cumulative work has expanded substantially the catalogue of proteins (into the hundreds) known to undergo S-nitrosylation in vitro and/or in vivo, as well as emphasized the mechanistic importance of protein denitrosylation, trans-S-nitrosylation, and S-thiolation in modulating the biological effects of S-nitrosoproteins (59, 144).

S-nitrosylation in the cardiovascular system

Specific to cardiovascular (patho)physiology, protein S-nitrosylation appears to play a role in virtually every aspect of cardiac function, including the regulation of inflammation, apoptosis, and angiogenesis that contribute to atherogenesis (79, 130); nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activity that modulates blood vessel tone (31); trans- and intramyocyte Na2+, Ca2+, and K+ flux that regulates myocardial contractility and electrophysiologic signaling (13); cardiovascular responses to hypoxia (129); mitochondrial bioenergetics in vascular tissue (22); and platelet function, among others (19, 34, 127, 134) (Table 1). Thus, a central focus of current research in the field is the relationship between S-nitrosylation and the pathogenesis of ischemic heart disease, ischemic preconditioning, pulmonary hypertension, and cardiac arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation and cardiomyopathy-associated ventricular fibrillation. Protein S-nitrosylation is also implicated as a key mechanism of action for many widely used cardiovascular pharmacotherapies, including HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins), and, possibly, combination isosorbide dinitrate/hydralazine (4, 28).

Table 1.

Key S-Nitrosylation Targets Important in Cardiovascular (Patho)Physiology

| S-nitrosothiol target | S-nitrosylation site | Functional effect(s) | Pathophysiological relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glutathione | Cys2 | Vasodilation | Atherosclerosis |

| Platelet inhibition | Stroke | ||

| ↓ ICAM-1 | |||

| ↓ MMP-9 | |||

| Human serum albumin | Cys34 | NO• storage form and carrier | Sickle cell anemia |

| Vasodilation | Essential hypertension | ||

| Platelet inhibition | Pre-eclampsia | ||

| Atherosclerosis | |||

| Arterial injury (i.e., following balloon angioplasty) | |||

| eNOS | Cys101 (within zinc-tetrathiolate) | Tonic suppression of eNOS | S-nitrosylation as a regulatory mechanism by which NO inhibits eNOS activity |

| sGC | Cys122 | Inhibition of sGC activity | Tolerance to nitrate therapy |

| Hemoglobin | Cys93 | (Hypoxic) vasodilation | Sickle cell anemia |

| Pulmonary hypertension | |||

| Essential hypertension | |||

| Ischemic stroke | |||

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | |||

| Angiotensinogen | Cys18 | Inhibits renin binding | Essential hypertension |

| Cys138 | Pre-eclampsia | ||

| Hcy | Site not yet determined | Decreases Hcy-induced oxidant stress and apoptosis | Atherosclerosis |

| Mitochondrial complex I | 34 candidate thiols | Decreases mitochondria-derived oxidant stress | Protective against ischemia reperfusion injury |

| p47phox (NADPH oxidase) | C378 (predicted) | Decreases NADPH oxidase-derived oxidant stress | Protective against ischemia reperfusion injury |

| Cyclooxygenase-2 | 13 candidate thiols | Increased synthesis of prostaglandin I2 | Protective against ischemia reperfusion injury |

| L-type Ca2+channel | Site not yet determined | Modulates intracellular Ca2+ in ventricular myocytes | ↓ in CHF→ventricular fibrillation |

| RyR2 | 89 candidate thiols | Modulates sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ flux | Promotes normal myocardial contractility and electromechanical function in CHF |

| IKs channel | Cys445 | Shortens myocyte action potential | Modulates chronotropic responses to autonomic stimulation. |

| N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor | Cys91 and Cys264 | Inhibition of Weibel-Palade body exocytosis | Protective against vascular inflammation and thrombosis |

| MMP-9 | Cys99 | Promotes neuronal apoptosis and neuronal tissue injury | Ischemic stroke |

CHF, congestive heart failure; Cys, cysteine; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; Hcy, homocysteine; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; MMP, matrix metalloproteinases; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NO•, nitric oxide; RyR, ryanodine receptor; sGC, soluble guanylyl cyclase.

This review of the S-nitrosoproteome aims to discuss this multifaceted biochemistry of the thiol proteome through the prism of cardiovascular medicine. Here, we will provide a contemporary perspective on the biochemistry of S-nitrosothiols, discuss current techniques in use for detecting S-nitrosylated proteins in vitro and in vivo, present novel proteins known to undergo S-nitrosylation and the associated downstream biological effects of this post-translation modification, and consider potential therapeutic strategies that seek to capitalize on S-nitrosylation as a means by which to modify cardiovascular function.

Biochemistry of S-Nitrosothiols

Nitric oxide is a free radical gaseous molecule that contains a nitrogen atom, an oxygen atom, and an unpaired single electron. In mammalian cells, endogenous NO• is synthesized primarily from L-arginine and molecular oxygen (O2) in a reaction catalyzed by NOS. However, in genetically engineered NOS-deficient mice, basal levels of vascular NO• are detectable, demonstrating the importance of NOS-independent mechanisms for NO• synthesis in vivo (102). One such mechanism by which this occurs involves anaerobic bacterial flora present in the mammalian oral cavity, which are rich in nitrate reductase enzymes and, thus, may convert dietary sources of nitrate (NO3−) to nitrite (NO2−). In turn, it is possible that under conditions of tissue ischemia or extreme acidosis, such as is present in the gastric lumen (pH≤3), acidified nitrite may serve as a nitrosating species. Protonation of NO2− produces nitrous acid (HNO2), which spontaneously decomposes to NO• according to the following sequential reactions: 2HNO2→N2O3+H2O, N2O3→NO•+NO2• (88, 124).

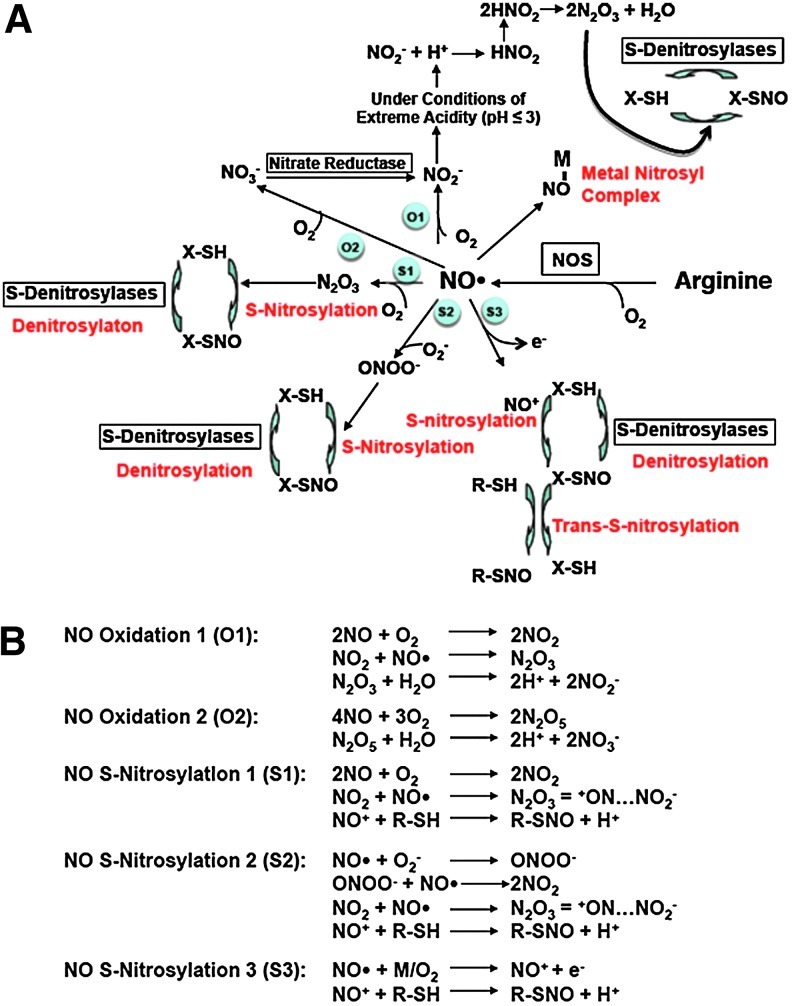

As a free radical, NO• interacts readily with transition metals, other free radicals, and O2 to form higher oxides of nitrogen (Fig. 1A). In turn, these various nitrogen oxide species range from highly reactive (e.g., NO2, N2O3, N2O5, ONOO−) to relatively stable (NO2− and NO3−). With respect to S-nitrosothiol formation, it should be noted that NO• alone does not spontaneously react with thiol groups. Rather, the formation of a covalent bond between NO• and the cysteine sulfur atom occurs through the synthesis of other reactive nitrogen oxide species. For example, N2O3, a strong nitrosylating agent, releases spontaneously a nitrosonium ion (NO+) that functions as an electrophile, capable of nucleophilic attack on the sulfur atom to form -S-NO (16, 33, 40). Nitrosonium may also be formed directly from NO• in the presence of an electron acceptor, such as a transition metal or O2 (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Nitric oxide (NO•) metabolism in mammalian cells. (A) NO• synthesized from L-arginine by nitric oxide synthase (NOS) may bind to transition metals (NO-M), undergo oxidation in the presence of molecular oxygen (O2), or interact with superoxide (•O2−) to form peroxynitrite (ONOO−). In the presence of O2, NO• may be converted to nitrosonium (NO+), an electrophile that interacts with nucleophilic thiols to form S-nitrosothiols (SNO). Additionally, under conditions of extreme acidity (pH≤3), protonation of NO• yields the formation of nitrous acid (HNO2), which is a substrate for the synthesis of the nitrosylating agent, nitrogen trioxide (N2O3). S-Nitrosothiol denitrosylation may occur enzymatically or through nonenzymatic exchange with free thiols. Encircled blue labels correspond to reactions that are described in greater detail in (B). M, transition metal (electron acceptor). Adapted from Guikema et al. (50a)

The relative nucleophilicity of common biologically relevant functionalities is R-S−>R-NH2>R-COO−≈R-O− (58). Accordingly, the thiol group of cysteine, particularly when present in the ionized state (i.e., thiolate [R-S−]), is the strongest nucleophile among protein functionalities. Thus, NO+ preferentially attacks the cysteinyl thiol to form an S-nitrosothiol. The predicted pKa of thiols in vitro is ∼8, but in biological systems the pKa may be lower in the presence of a positively charged microenvironment. In turn, differences in the reactivity of cysteinyl thiols are a predictor of susceptibility to S-nitrosylation. For example, serum albumin's single free cysteine (Cys34) has an anomalously low pKa (∼5) rendering it readily reactive toward electophiles. In addition, PTEN, a member of the tyrosine kinase phosphatase superfamily of proteins, contains a C(X5)K sequence at its active site. The pKa of this cysteine is also low (∼5); thus, S-nitrosylation at this site occurs readily when PTEN is exposed to NO donors (146).

Despite the covalent nature of the S-NO bond, in the presence of transition metals (i.e., Fe2+ and Cu+) and reducing agents (i.e., ascorbate), S-NO may decompose by homolytic or heterolytic cleavage resulting in the release of NO•, NO+, or NO− (59, 121, 123, 129). Under physiologic conditions, S-nitroso-glutathione reductase (GSNOR) and thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) are two important denitrosylases. A proposed mechanism by which these enzymes induce the release of NO• from S-nitrosothiols is provided in Figure 2. Denitrosylation of S-nitrosothiols by TrxR may involve the formation of higher oxidative intermediates of cysteine, including the disulfide form. For example, denitrosylation of S-NO-caspase is purported to involve the nucleophilic attack of the target cysteine by the N-terminal Cys thiolate of Trx, which results in the formation of an intermolecular disulfide bridge. An additional attack of the disulfide bridge by the remaining C-terminal cysteine releases caspase from Trx and induces the formation of a disulfide bond within Trx (9). S-nitrosoprotein metabolism may involve the formation of other cysteinyl oxidative intermediates as well, such as in the case of S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO)-modified glutathione reductase, in which Cys63 is ultimately oxidized to form sulfenic acid (R-SOH) and sulfinic acid (R-SO2H) (6).

FIG. 2.

Two proposed mechanisms for denitrosylation. (A) The glutathione/S-nitroso-glutathione reductase (GSH/GSNOR) system requires nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), reduced glutathione (GSH), and S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) for selective denitrosylation of GSNO. Trans-S-nitrosylation from RSNO to GSH forms GSNO. In the presence of NADH, GSNO is converted to glutathione N-hydroxysulfenamide (GSNHOH) by GSNOR. (B) Thioredoxin (Trx) reduces RSNO to induce denitrosylation in a reaction that generates NO• or HNO2 and the oxidized form of thioredoxin (TrxSS). Reduction of TrxSS to recycle Trx is catalyzed by thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) in the presence of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAPDH). Se, selenium.

The stability of S-nitrosothiols is also affected by trans-S-nitrosylation and S-thiolation (60). In trans-S-nitrosylation, the nucleophilic thiolate of R′SH attacks the nitrogen of S-nitrosothiols to form R′SNO and RSH, whereas in S-thiolation, the nucleophilic thiolate interacts with the sulfur of an S-nitrosothiol to form a mixed disulfide and NO− (Fig. 3). Importantly, nitrogen is more electrophilic than sulfur. Thus, trans-S-nitrosylation, which involves the attack on the nitrogen of an S-nitrosothiol by a nucleophilic thiolate, is predicted to be more favorable than S-thiolation, in which the thiolate attacks a sulfur. Indeed, in in vitro studies, a higher concentration of S-nitrosothiols is required in the S-thiolation reaction to yield mixed disulfides (76), whereas trans-S-nitrosylation is a reversible second order reaction with rate constants of 1–100 M−1·s−1 and equilibrium constants close to 1 (61). Trans-S-nitrosylation, therefore, occurs under normal physiological conditions (106, 116), while S-thiolation likely prevails under conditions of prolonged nitrosative stress.

FIG. 3.

Trans-S-nitrosylation and S-thiolation reactions. In trans-S-nitrosylation, the nucleophilic thiolate (R′S−) of R′SH attacks the nitrogen of an S-nitrosothiol to form R′SNO and RSH, whereas in S-thiolation, the nucleophilic thiolate interacts with the sulfur of an S-nitrosothiol to form a mixed disulfide (RSSR′) and NO−.

Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), which is present on the cell membrane surface and catalyzes thio–disulfide exchange reactions, is believed to facilitate exogenous NO• entry into cells, possibly via trans-S-nitrosylation reactions. The potential for PDI-mediated trans-S-nitrosylation has been demonstrated previously using a NO•-dependent oxymyoglobin oxidation assay (147). In the presence of GSNO, PDI caused a 15-fold increase in the NO•-dependent conversion of oxymyoglobin to metmyoglobin compared to GSNO alone. These data suggest that PDI catalyzes the trans-S-nitrosylation of NO• from GSNO to oxymyoglobin to promote the formation of metmyoglobin through the following two reactions: Fe2+-O2+NO•→Mb-Fe2+-O2NO→Mb-Fe3++NO3 (26). Moreover, the molecular inhibition of cell surface PDI is associated with decreased GSNO-stimulated activation of (intracellular) sGC in human erythroleukemic cells, indicating a functional importance of PDI in facilitating the transfer of bioavailable NO• from extracellular S-nitrosothiols to the intracellular compartment. Importantly, data derived from human vascular endothelial cells and lung hamster fibroblasts indicate that the Km for denitrosylation of bovine serum albumin (BSA)-NO by PDI is 12–30 μM, or ∼17% of the predicted Vmax (109); thus, the contribution of PDI to denitrosylation under physiological conditions is unclear. Furthermore, the role of PDI in maintaining endogenous NO• levels in vivo is less well characterized, owing, in part, to a lack of mammalian PDI-knockout models (56).

It is important to note that mitochondria represent the primary subcellular location of S-nitrosoprotein formation in eukaryotic cells. Mitochondria are a key site of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation owing to the oxygen-rich environment of the intramitochondrial space and the electron transport chain, which plays host to the thermodynamically favored reaction in which one electron is transferred from molecular oxygen to form superoxide (•O2−) (98). In turn, the interaction of •O2− with exogenous or endogenous NO• forms the nitrosating agent(s) peroxynitrite (ONOO−) and/or N2O3. Pharmacological inhibition of the electron transport chain or removal of mitochondria results in a significant decrease in S-nitrosoprotein formation, such as has been observed in endothelial cells (145).

Detecting S-nitrosothiols: Contemporary Proteomic and Molecular Strategies

Several factors hamper efficient detection of biological S-nitrosothiols. First, although stable under physiologic conditions (pH 7.4, 37°C), S-nitrosothiols tend to degrade in the presence of microenvironmental perturbations to pH and temperature, and in the presence of light or transition metal ions (120). Secondly, even in S-nitrosothiol-rich tissues, the concentration of S-nitrosothiols relative to the total protein thiol content is low (86). Even basal levels of S-nitroso serum albumin (SNO-SA), a relatively abundant S-nitrosothiol species in human plasma, is often below assay detection limits; when detectable, concentrations of 30–40 nM have been reported (81, 110). This observation does not, however, indicate that absolute S-nitrosoprotein levels are necessarily negligible within a given biological compartment, since rapid degradation and/or increased reactivity of S-nitrosoproteins could produce a negative bias in detection results. Thirdly, radiolabeling of a nitroso group, which would enhance detection efficiency, is not chemically possible (60).

To overcome these obstacles, early S-nitrosothiol identification methods relied on prototype-generation [15N] nuclear magnetic spectroscopy or mass spectrometry, and were limited to analyzing only purified thiol-containing proteins, such as BSA, cathepsin B, and tissue plasminogen activator (128). However, contemporary proteomic- and molecular-based strategies afford the investigation of S-nitrosylation of lower abundance proteins and under a wider range of empiric conditions, including in vivo.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

In-tandem, liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) offers the site-specific identification of the S-nitroso bond within peptide fragments. However, sample preparation requirements and laser energies necessary for performing conventional LC-MS, such as matrix-assisted laser desorption (MALDI)/ionization reflection time-of-flight (ReTOF) mass spectrometry or electrospray ionization (ESI), often induce S-nitrosothiol degradation that results in poor detection yields (85). At the expense of limited peptide coverage rates, however, ESI LC-MS experimental methods may be optimized for detecting S-nitrosylated proteins as a +29 Da ion (+NO• and −H) (64, 96). Overall, despite increasingly sophisticated LC-MS methods (such as quadrupole time-of-flight MS) and software analysis programs, coupling LC-MS with an upstream strategy designed to stabilize S-NO groups before LC-MS remains a more effective strategy for S-nitrosothiols detection compared with LC-MS alone, particularly in vivo. In fact, direct detection by LC-MS of S-nitrosoproteins in vivo was only recently reported from experiments conducted in phytochelatins isolated from Arabidopsis thaliana cells (30, 136). Proteins from these flowering plant-derived cells are typically cysteine-rich, and, thus, are optimal for analyzing post-translational modifications of cysteinyl thiols by LC-MS. The application of LC-MS alone for the direct detection of protein S-nitrosylation in mammalian cells in vivo, however, has not yet been reported.

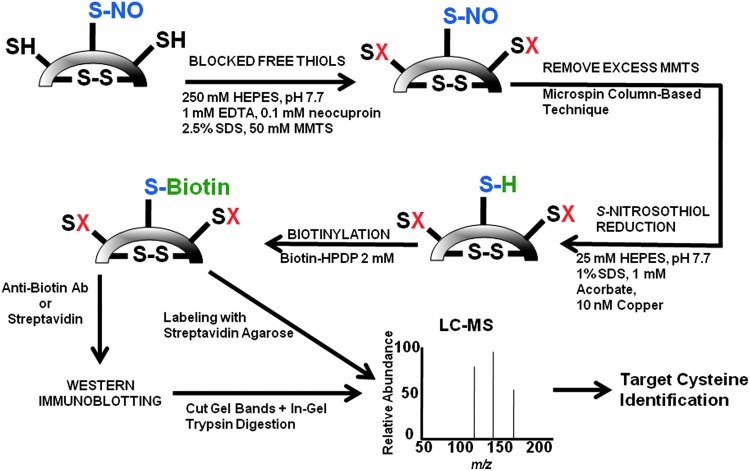

Biotin-switch assay

The biotin-switch assay exploits the selective reactivity of biotin with reduced cysteinyl thiols as part of a three-step proteomic strategy to detect S-nitrosylated proteins (Fig. 4). Jaffrey et al. originally used this technique in murine brain tissue to demonstrate S-nitrosylation of numerous proteins involved in cell metabolism, structure, and signaling (64). To accomplish this goal, an experimental system was developed in which protein samples were incubated with methyl-methanethiosulfonate (MMTS) to bind free thiols selectively, but not S-nitrosylated thiols or pre-existing disulfide bonds. With free thiols blocked by MMTS, protein samples are then exposed to a reducing agent that converts S-nitrosothiols to thiols. In the final step, reduced S-nitrosylated thiols are labeled with N-[6-(biotinamido)hexyl]-3′-(2′-pyridyldithio)propionamide (biotin-HPDP) and recovered following sample elution. The presence of biotinylated cysteinyl thiols, which represent S-nitrosylated proteins, may then be assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (using anti-biotin antibodies or streptavidin), LC-MS performed on in-gel trypsin digested target bands, or LC-MS on bands or spots excised from two-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis. Numerous iterations of this procedure have since been described, which aim to enhance detection efficiency and range of coverage by utilizing various alternative compounds (144). Substitution of biotin with a His-tagged peptide, for example, may provide a detection advantage as some have suggested that biotin (but not the His-tag) is often lost during sample elution (17, 136).

FIG. 4.

Biotin-switch method for the detection of S-nitrosothiols. Free cysteines (-SH) are blocked (-SX) following exposure of protein samples to methyl-methanethiosulfonate (MMTS). Excess MMTS is removed by running the sample through a microspin column or by protein precipitation with acetone. The sample is then treated with ascorbate and copper sulfate. Ascorbate reduces Cu2+→Cu3+, which cleaves S-NO bonds, and previously S-nitrosylated (now free) cysteines are labeled with N-[6-(biotinamido)hexyl]-3′-(2′-pyridyldithio)propionamide (biotin-HPDP). Biotin-labeled proteins are subjected to Western immunoblotting, target bands are cut from the gel, and then trypsin-digested before liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis. Alternatively, streptavidin agarose may be used to segregate biotinylated proteins before LC-MS. Adapted from Kettenhofen et al. (71).

A key limitation of the conventional biotin-switch assay is poor detection of proteins that undergo S-nitrosylation in vivo. Moreover, this method does not provide information regarding biological, stereoisomeric, or other biochemical factors that regulate the formation of target S-nitrosothiols. Methods to develop a model for predicting protein- and cysteine-specific targets of S-nitrosylation have relied on alternative methods. Doulias et al. exploited the reactivity of phenylmercury compounds with S-nitrosocysteine to induce the formation of a stable thiol–mercury bond, and then used an organomercury resin and a phenylmercury-polyethyleneglycol-biotin compound to capture S-nitrosylated proteins and peptides. Through a complex bioinformatic analysis of S-nitrosoproteins isolated from murine livers, they demonstrated that by increasing the accessibility of cysteine to NO•, factors that increase the probability of S-nitrosylation are the adjacency of cysteinyl thiols to a charged amino acid (within 6-Å distance) in the tertiary structure of the protein, and cysteinyl thiol positioning within protein α-helices (25).

Often cited limitations to the biotin switch method include the nonspecific effects of ascorbate, which may reduce disulfide bonds to enable the false-positive identification of S-nitrosation sites (36, 38). Murray et al. have recently reported on the use of the cysteine mass tag (cysTMT) reagent, which offers several technical advantages over the use of conventional biotin for the specific identification of S-nitrosylation sites. First, cysTMT provides a permanent mass tag that enhances LC-MS analysis sensitivity. Second, cysTMT allows for the ability to fragment up to six reporter ions, which, in turn, allows for multiplex quantitative mass spectrometry analysis. Third, the cysTMT switch assay utilizes a low pH elution from the TMT affinity resin for reduction, rather than ascorbate, to protect mass tag binding to the modified cysteine(s) (100). Their methods identified 220 S-NO-modified cysteines on 179 proteins isolated from pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Relative quantification of the sensitivity of cysteines to S-nitrosylation was calculated according to the slope generated by the reporter ion intensity for each cysteine across a range of GSNO (as an NO donor) concentrations.

Two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis

The cyanide dye-labeling (CyDye)-switch assay utilizes CyDye for in-gel fluorescence scanning, enabling direct comparative proteomic analysis of S-nitrosoproteins between two or more samples (71). Modeled closely after the biotin-switch assay principle, the CyDye-switch method incorporates difference gel electrophoresis (DIGE) technology to visualize differences in protein S-nitrosylation profiles between control and treated (i.e., S-nitrosylated) samples (71). With this protocol, following the thiol blocking and reduction steps (as outlined in the biotin-switch method), free thiols in both control and experimental samples are labeled with a succinimidyl ester of the cyanine dyes, Cy3 (green) or Cy5 (red) (Fig. 5A). In the control condition, cysteinyl thiols unblocked by MMTS (i.e., cysteinyl thiols previously involved in a disulfide bond, and now reduced) will fluoresce green on a 2D gel. In turn, cysteinyl thiols unblocked by MMTS in the experimental condition (i.e., S-nitrosylated cysteinyl thiols or reduced disulfide bonds) fluoresce red (Fig. 5B). Samples are then run simultaneously on a 2D gel, and images acquired using a dual laser scanning device or xenon arc-based instrument equipped with different excitation/emission filters to generate two separate images, one in red and one in green (108). Band differences present after gel overlay analysis indicate modified proteins and, thus, represent targets for LC-MS analysis. It is important to note that Cy labeling induces a subtle shift in the molecular mass of the target protein, which is responsible for an elevated false identification rate of excised spots on LC-MS analysis (108, 135). Thus, poststain treatment with the SYPRO Ruby dye is often necessary to enhance the accuracy of target band excision before LC-MS analysis (71, 108, 135, 150).

FIG. 5.

Cyanide dye-labeling (CyDye)-switch method for the detection of nitrosylated cysteinyl thiols. (A) In the CyDye-switch method, protein samples are subjected to the thiol blocking and reduction steps as outlined in the biotin-switch assay method. Control samples are then labeled with green fluorescence Cy3 dye and experimental (i.e., S-nitrosylated) samples are labeled with red fluorescence Cy5 dye. (B) Using 2D-gel technology, separation of proteins occurs according to gel-specific gradients for molecular weight and pH. Equal protein amounts from both control and experimental conditions are then analyzed by difference gel electrophoresis (DIGE), which exploits differences in Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescence colors to identify cysteinyl thiols modified (i.e., S-nitrosylation or disulfide bond formation) in the experimental conditions. In the example provided, DIGE analysis of mixed protein samples (labeled Merged) reveals the presence of green protein spots that reflect proteins detected with Cy3, but not Cy5 labeling (white arrows). Conversely, proteins labeled by Cy5, but not Cy3 (red circle), reflect cysteinyl thiol modification(s) induced under the experimental conditions. In the merged gel, a color gradient from green to red for protein spots is observed: proteins with greater cysteinyl thiol modification are observed to fluoresce red more strongly. Identification of proteins and specific cysteinyl thiol modification(s) is performed by LC-MS analysis on excised gel spots. Figure 5A is adapted from Kettenhofen et al. (71); Figure 5B is reproduced with permission from Huang et al. (61a)

Resin-assisted capture of S-nitrosoproteins

Detection of S-nitrosylated proteins through a resin-assisted capture method is among the latest modifications of the biotin-switch assay. In this methodology, following the free thiol blocking and reducing steps discussed in the biotin-switch assay, nascent thiols are covalently trapped with a thiol-specific resin-bound 2- or 4-pyridyl functionality (37). Samples are then eluted with a reductant, separated electrophoretically by SDS-PAGE, and visualized using Western immunoblotting or a specialized stain. Resin-trapped thiols may also undergo trypsin cleavage before isotopic labeling, which improves LC-MS detection rates of target proteins. In Langendorff-perfused hearts, Kohr et al. used this methodology to demonstrate the S-nitrosylation of 31 proteins in response to ischemic preconditioning (77).

Antibody-based methods of detecting S-nitrosoproteins

The use of an antibody against conjugated S-NO has been reported for immunoblotting, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and immunohistochemistry analyses in situ (21). The use of anti-S-NO antibodies, however, requires a priori verification of antibody specificity to the S-nitrosylated form of the target protein, and, in general, is unable to provide complete identification of all cysteines involved in S-nitrosylation of a particular protein (48). Moreover, it has been suggested that the stereometric effects of the S-NO bond on protein structural conformation may in and of itself impede recognition of the target (i.e., S-nitrosylated) protein by anti-S-NO antibodies, thereby limiting further the sensitivity of immunoblotting in these experiments.

S-Nitrosylation in Cardiovascular (Patho)physiology

Glutathione

Glutathione is a low-molecular-weight tripeptide that contains a cysteine bound to the carboxyl group of the glutamate side-chain. In humans, glutathione is present in all tissues important for vascular function, including blood plasma and vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells, where it is found in relatively high (mM) concentrations (121). Nitric oxide reacts readily with glutathione to form GSNO, which is the most abundant intracellular S-nitrosothiol in human tissue, by several potential mechanisms. The formation of GSNO likely occurs in a reaction between NO+ and the reactive nucleophilic sulfur present in glutathione (60, 84). Alternatively, NO• may react with O2 to form NO2−, which then may react with NO• to generate the nitrosylating agent N2O3 (see Biochemistry of S-nitrosothiols section) (54, 75). The kinetics for the formation of GSNO has been determined and (under aerobic conditions) occurs with a rate constant of 1.5–3.0×105 M−1·s−1, approximately three orders of magnitude greater than that between NO• and nonsulfhydryl amino acids (75, 141).

The interplay between S-nitrosylation and glutathiolation is illustrated by the effect of glutathione on nitrosylated aldose reductase, which is a stress response protein that catalyzes the reduction of various aldehydes and maintains a cardioprotective role during ischemia-reperfusion injury (66). Treatment of the human recombinant form of aldose reductase with the nonthiol NO•-donor DEA-NO (0.5 mM) resulted in the aldose reductase S-nitrosylation at Cys298 and subsequent enzyme activation. S-NO-aldose reacted with glutathione resulting in the glutathiolated aldose reductase and a decrease in enzyme activity by ∼50%. Moreover, this reaction was reversible, as coincubation of the glutathiolated aldose reductase with reduced glutathione generated the reduced form of the protein (5), which could be re-S-nitrosylated in the presence of GSNO to restore enzyme activity.

Glutathione is also involved in trans-S-nitrosylation reactions within the intracellular compartment (84). In vitro, NO• transfer to glutathione and cysteine is rapid and pH-dependent (5.14 μM/min and 4.69 μM/min at pH 9.0, respectively). Through trans-S-nitrosylation, and, ultimately, GSNO denitrosylation, platelet inhibition and vasodilation can be elicited in endothelialized aortic rings (84). On the cell surface, PDI catalyzes thiol–disulfide exchange reactions, and has been shown to react with NO• to promote NO• transfer from the extracellular to intracellular compartment likely involving S-nitrosothiol intermediates (8, 62, 139, 147). In fact, S-nitrosylation of PDI on the platelet cell surface is one mechanism by which GSNO inhibits platelet aggregation (142)

GSNO may also interact with deoxyhemoglobin to form glutathione, NO•, and ferric hemoglobin (k=0.01 to 0.03 M−1·s−1) (123) in a reaction that occurs more readily in high oxygen tension. Hemoglobin is rapidly S-nitrosolated by nitric oxide that is generated from this reaction (123). The inverse relationship between pO2 and the propensity for GSNO-derived NO• to S-nitrosylate hemoglobin to form S-nitrosylated hemoglobin (SNO-Hb) supports a role for oxygen tension as a mitigating factor in the bioactivity of NO• (see Hemoglobin section, below) (47, 148). In the presence of reactive thiols, GSNO is metabolized in a rapid and cell-independent manner (47, 148). Additionally, GSNO may be irreversibly converted to GSNHOH (glutathione N-hydroxysulphenamide) by the alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme GSNOR (10). Indeed, GSNOR antagonism to enhance bioavailable GSNO appears to hold pharmacotherapeutic potential. Sanghani et al. recently reported three novel compounds that selectively inhibit GSNOR, resulting in an increase in GSNO in macrophages, decreased NF-κB activation, and increased cGMP formation (114). The benefits of direct GSNO administration on vascular responses to vascular injury have also been tested. In a murine in vivo model of traumatic brain injury, infusion of GSNO decreased intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 levels and expression of inducible NOS (iNOS) in macrophages (72). Similar beneficial effects of GSNO therapy have been reported in a rat model of ischemic stroke (73), and in decreasing recurrent carotid events in patients with atherosclerotic carotid disease (67).

Human serum albumin

Human serum albumin (HSA) is a single polypeptide consisting of 585 amino acids, including 35 cysteines and 17 disulfide bridges (104). In human plasma, S-nitroso-serum albumin (SNO-SA) accounts for an impressive 82% of all S-nitrosothiols; thus, it follows that the single free cysteine (Cys34) (pKa=∼5) is observed to be highly reactive with nitrogen oxide species (126). The trans-S-nitrosylation kinetics of SNO-SA are slow relative to other S-nitrothiols. For example, under physiologic conditions (pH 7.4, 37°C), the second order rate constant (k2) for S-nitroso-thiol exchange reactions between GSNO and N-acetyl-penicillamine is 0.9 M−1·s−1, whereas that for SNO-SA is 9.1 M−1·s−1. Together with the high abundance of SNO-SA in plasma, these kinetic data implicate albumin as a leading candidate for the major long-term NO• storage adduct under physiologic conditions (95).

The functional effects of SNO-SA were originally described in denuded rabbit aortic strips in which a concentration-dependent decrease in vascular tone was observed as was inhibition of platelet aggregation; at a SNO-SA concentration of 10 μM, an ∼80% decrease in both measures could be elicited (126, 128). SNO-SA is protective against ischemia/reperfusion injury in the skeletal muscle and myocardial tissue. In a rabbit model of hindlimb ischemia/reperfusion injury, SNO-SA administration 30 min before reperfusion or ischemia resulted in sustained increases in NO• levels (assessed continuously by porphyrinic microsensor in the wall of the femoral artery), and decreased vasoconstriction and interstitial edema following reperfusion (51, 52).

The protective effects of SNO-SA-mediated increases in bioavailable NO• has been investigated in other cardiovascular diseases, including sickle cell anemia, hypertension, and vascular injury following transluminal coronary arterial stent deployment (24, 68, 90). Conversely, impaired NO• release from SNO-SA may be an under-recognized pathophysiological mechanism in certain vascular diseases. For example, in pre-eclampsia, a hypertensive condition of pregnancy, decreased circulating levels of ascorbate, a key modulator of NO• release from S-nitrosothiols, are associated with increased SNO-SA levels, but decreased SNO-SA denitrosylation and NO•-dependent vasodilation (137). This observation notwithstanding, there are insufficient data derived from relevant animal models or patients with pre-eclampsia to characterize the mechanistic contribution of ascorbate deficiency to the hypertensive response in this disease.

Endothelial NOS

Endothelial NOS (eNOS) is a homodimeric enzyme and the primary source of endogenously derived NO• in vascular tissue. Activation of eNOS releases suppression of electron transfer between the N-terminal heme-binding (i.e., oxygenase) and C-terminal reductase domains to catalyze the 5-electron oxidation of the guanidino nitrogen of L-arginine that generates NO• (2) [for a complete review of eNOS, see (27)]. It is believed that S-nitrosylation of eNOS at Cys101, a zinc-tetrathiolate cysteine, modulates the tonic suppression of eNOS catalysis, whereas activation of eNOS results in rapid denitrosylation (31). S-Nitrosylation of eNOS may occur secondary to eNOS-derived NO• or via pharmacologic NO• donors, but requires translocation of eNOS to the cell membrane via acylation-dependent post-translational modification(s) of eNOS (32). For example, acylation-deficient eNOS, which is expressed exclusively in the cytosol, exhibits levels of S-nitrosylation that are significantly lower than wild-type forms of the enzyme (31, 32).

The mechanism by which S-nitrosylation inhibits enzyme activity appears to be as a consequence of eNOS uncoupling. Compared to control, treatment of aortic endothelial cells with NO• to induce eNOS S-nitrosylation (as detected by optical absorption spectroscopy) decreases eNOS dimer expression and activity levels, while increasing eNOS monomer levels. Site-directed mutation of Cys99 (within the zinc tetrathiolate cluster), however, induces a relative increase in monomer expression levels compared to dimer expression levels following sample treatment with NO•, supporting the postulate that the tetrathiolate cluster is involved in S-nitrosylation-dependent regulation of eNOS structure and function (112). The subcellular effects of eNOS-derived NO• on S-nitrosylation of other proteins have been evaluated. In COS cells transiently transfected with a nuclear localized eNOS fused with a monomeric red fluorescent protein, eNOS stimulation enhanced the fluorescence signal in the Golgi and the cell nucleus (63). In the Golgi, S-nitrosylation of N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) is associated with decreased cellular trafficking of proteins, including the von Willebrand factor (93).

Soluble guanylyl cyclase

sGC is a heterodimeric enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of cytosolic GTP to cGMP, a critical secondary messenger necessary for normal PKG-dependent vascular smooth muscle relaxation. Nitric oxide derived from eNOS, iNOS, or pharmacologic NO• donors (e.g., nitroglycerin, isosorbide dinitrate, isosorbide mononitrate, etc.) interacts with the sGC prosthetic heme group located near His105 on the β1-subunit to stimulate sGC activation ∼20-fold above basal levels. Recently, Fernhoff et al. proposed that sGC activation by NO· occurs in an hierarchical manner (35). In this model, sGC activation by NO•-heme binding (1-NO) is enhanced further by the binding of NO• to regulatory thiol(s) (xsNO) in sGC. Their work using recombinant rat sGC in vitro demonstrated that the Vmax for GTP turnover was 14.7 versus 64.1 versus 3610 nmol·min−1·mg−1 for the basal, 1-NO, and xsNO states, respectively, indicating that the S-NO form is the most active form of sGC. The regulatory function of S-NO binding on sGC activation was confirmed by experiments in which sGC was exposed to MMTS, which modifies thiols through the formation of methyl disulfide. These investigators observed that without affecting sGC activity under basal conditions, MMTS inhibited significantly NO•-stimulated sGC activation.

Prolonged use of NO• donor pharmacotherapy, however, results in a diminished clinical effect. Several potential mechanisms to account for this observation have been theorized, including, among many others, depletion of reactive sulfhydryl groups necessary for enzymatic release of NO• from nitrovasodilators and increased endothelial production of free radicals, such as superoxide (•O2−) that oxidizes the heme ligand of sGC to decrease NO•-sensing by sGC (20, 35, 86, 107, 128, 132, 148).

S-nitrosylation of sGC may be involved in the development of NO• donor tachyphylaxis. sGC contains three functional cysteinyl thiols on the β1-subunit (Cys78, Cys122, Cys214) that regulate NO•-sensing by sGC (39). Of these, Cys122 is an established target of S-nitrosylation; when formed, S-nitrosylation of this cysteine diminishes sGC activity. In cultured aortic smooth muscle cells exposed to S-NO-cysteine to induce S-nitrosylation at Cys122, NO•-induced stimulation of sGC (by heme group nitrosylation) is decreased by 60% compared to cells exposed to NO• alone (115). Conversely, substitution of cysteine for alanine at position 122 prevents S-nitrosylation and partially restores NO•-stimulated sGC activation. The complete three-dimensional structure of mammalian sGC is unresolved, which hinders efforts to determine the precise mechanism accounting for this observation. Nevertheless, the possibility exists that S-nitrosylation of Cys122, which is situated near the NO•-sensing heme ligand of sGC, results in a conformational change in sGC that prevents normal NO• sensing by the enzyme.

Hemoglobin

S-nitrosylation of hemoglobin at Cys93 of the hemoglobin β-subunit (SNO-Hb) occurs in a predictable pattern according to fluctuations in the local partial pressure of oxygen (pO2). Under hypoxic conditions, hemoglobin assumes a tense (T) allosteric conformation. This conformation impairs the stability of covalent attachment of NO• to Cys93 owing to externalization of S-nitrosylated Cys93, which promotes its interaction with factors that induce denitrosylation. Conversely, at high pO2 levels, the relaxed state (R) of hemoglobin affords S-NO formation, since in this state Cys93 resides internally within the tertiary structure of hemoglobin (44, 65). The relationship between pO2 levels, hemoglobin allosteric conformation, and Cys93 (de)nitrosylation governs, in part, the phenomenon of hypoxic vasodilation. Sonveaux et al. proved this postulate by examining the effects of changes in the fraction of inspired O2 (FiO2) on NO• bioactivity and tumor perfusion in rats under conditions of normoxia or hyperoxia. In the former, tumor perfusion was decreased (consistent with vasodilation upstream of the tumor inducing a vascular steal phenomenon), whereas in the latter, NO• bioactivity from SNO-Hb was decreased, tumor perfusion was maintained, and blood pressure was increased (122).

Whether SNO-Hb regulates vascular tone by endocrine or paracrine signaling in vivo remains debatable. On the one hand, it is postulated that binding of NO• to deoxygenated heme in the circulation (forming Fe2+-NO) facilitates trans-S-nitrosylation to Cys93; upon deoxygenation, hemoglobin is converted from the R to the T state resulting in the release of NO• that may diffuse through the vascular endothelium and into smooth muscle cell layers to induce cGMP-dependent vasodilation (43, 127). On the other hand, although SNO-Hb is stable in purified solutions and erythrocyte lysates, experiments performed in erythrocytes acquired from human subjects has yielded SNO-Hb levels (69 nM in arterial samples, 46 nM in venous samples) far below that believed necessary for hemoglobin to function as a NO• reservoir in the circulation (44). Moreover, SNO-Hb levels tend to fall rapidly irrespective of oxygen tension or hemoglobin saturation, while ferricyanide stabilizes SNO-Hb levels, suggesting that the intrinsically reductive microenvironment within erythrocytes prevents long-term storage of NO• as SNO-Hb (43).

It has also been reported that the half-life of NO• is inversely proportional to the concentration of erythrocytes in a closed experimental system, independent of the hemoglobin concentration (83). Compared to solutions containing free oxyhemoglobin, the disappearance rate of NO• in the presence of erythrocytes is 650-fold slower. Since NO• is believed to traverse cellular membranes by passive diffusion, these findings suggest that a barrier to diffusion from the extracellular to intraerythrocytic compartment exists that impairs S-nitrosylation of hemoglobin in vivo. Collectively, these and other similar findings have raised speculation that despite the undisputed predilection for NO• to react with free hemoglobin, this is not a central mechanism for regulating NO• bioactivity in the setting of intact erythroyctes in vivo.

Clinical implications of SNO-Hb

Preclinical trials in humans have established that intravascular infusion of NO• influences blood vessel tone at remote sites; however, it is unresolved as to whether this occurs primarily due to free NO•, SNO-Hb, or a combination of both (111). In murine models of cerebrovascular injury, S-nitrosylation of hemoglobin is associated with a decrease in subarachnoid hemorrhage size (119) and ischemic stroke severity (69). Owing to the beneficial effect of S-nitrosylation on the affinity of hemoglobin for O2, Gladwin et al. recently investigated the role of point-of-care inhaled NO• therapy in the management of sickle cell disease-associated vaso-occlusive crises (42). They tested the hypothesis that inhaled NO• therapy, through inducing SNO-Hb formation and/or improvements in local oxygen tension, is an effective strategy by which to attenuate erythrocyte sickling, improve microcirculatory perfusion during vaso-occlusive crises, and reduce patient-reported symptoms. In that study, treatment with inhaled NO• did not meet the predetermined clinical end points, although low plasma levels of the stable NO• metabolite, NO2−, observed in patients receiving inhaled NO• suggests inefficiency in the method of delivery of inhaled NO• as a confounding factor in the study.

Angiotensinogen

Angiotensinogen is an α-2 globulin and member of the serpin family of proteins. By catalyzing the conversion of renin to angiotensin I (Ang I), angiotensinogen is a key determinant of the rate-limiting step for synthesis of the pressor hormones angiotensin II (Ang II) and aldosterone (91, 149). The crystal structure of angiotensinogen was recently resolved to 2.1 Å, allowing for analysis of coordinated changes in angiotensinogen that modulate renin–angiotensin binding, and, thus, angiotensinogen function (149). Zhou et al. reported that formation of a disulfide bridge involving Cys18-Cys138, two angiotensinogen cysteines conserved across all species, is a critical determinant for renin binding (41, 149). Reductive cleavage of this disulfide bond mediated by glutathione disulfide or glutathione, for example, changes the structure of the renin-binding pocket of angiotensinogen to a less favorable conformation and, thereby, decreases angiotensinogen activation. Moreover, incubation of reduced recombinant human angiotensinogen with S-nitroso-N-acetyl-D,L-penicillamine (SNAP) (1 mM) resulted in stoichiometric loss of Cys18 and Cys138, suggesting S-nitrosylation at these cysteines. In purified protein samples exposed to iodoacetamide to block free thiols followed by dithiothreitol (DTT) treatment to reduce the Cys18-Cys138 disulfide bond, treatment with SNAP resulted in a progressive decrease in detectable thiols, but an increase in NO• per mole of angiotensinogen. The latter is believed to reflect an accumulation of free NO• following stoichiometric S-nitrosylation of Cys18 and Cys138. Thus, S-nitrosylation of angiotensinogen at Cys18 and Cys138 is believed to regulate blood vessel tone by preventing the formation of functionally critical disulfide bonds involving these cysteines.

S-Nitrosylation in Cardiovascular Diseases

Vascular injury and ischemic heart disease

Pathological remodeling of atherosclerotic blood vessels following vascular injury may be attenuated through the effects of NO• on promoting vasodilation, inhibiting platelet activation, and limiting vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation (140). For example, the administration of NO• donor pharmacotherapy to patients for 6 months following coronary balloon angioplasty is associated with an increase in the luminal diameter of the treated atherosclerotic blood vessels (78). To explain this effect, it is believed that S-nitrosothiol denitrosylation offsets maladaptive cellular responses to balloon-induced arterial injury that contribute to vessel restenosis, including endothelial dysfunction, vascular smooth muscle cell migration, and proliferation, and extracellular matrix production. In support of this hypothesis is the observation that S-nitrosothiols exhibit high affinity for endothelium-denuded blood vessels. In a rabbit model of balloon arterial injury of the femoral artery, locally administered S-NO-BSA increased by 26-fold vascular accumulation of S-NO-BSA compared to uninjured vessels (90). Moreover, a polythiolated form of BSA enhanced further the favorable effects of S-NO-BSA on the intimal/medial ratio and extent of platelet deposition in the femoral artery following balloon-induced injury (90).

Hyperhomocysteinemia is believed to promote atherogenesis, in part, by increasing ROS-dependent endothelial cell apoptosis via upregulation of p53-dependent Noxa expression (79, 130). S-nitroso-homocysteine generated following induction of iNOS, however, exhibits decreased homocysteine-dependent ROS formation, p53-dependent Noxa expression, and endothelial apoptosis. Taken together, these data suggest that factors which impair S-nitrosylation of homocysteine may also contribute to the pathogenesis of hyperhomocysteinemia-associated vascular dysfunction.

Ischemic preconditioning is the development of tolerance to ischemia-induced myocardial injury following brief periods of impaired coronary arterial blood flow (101). Numerous myocytes, vascular endothelial, and vascular smooth muscle receptor-dependent molecular mechanisms, which regulate initiation of protective cell signaling pathways necessary for the beneficial consequences of preconditioning, have been described previously (29). A key cell surface receptor-independent determinant of ischemic preconditioning is endogenously synthesized NO•. The precise role of NO• in the biology of ischemic preconditioning remains unresolved: although there is evidence to suggest that high concentrations of NO• are toxic in various animal models of ischemia/reperfusion injury, the net effect of NO• is likely tied to its function as an intermediary that participates in various protective processes of ischemic preconditioning (23).

Early preconditioning is characterized by a large increase in bioavailable NO• owing to the robust activation of iNOS in the myocardial tissue that is stimulated by a decrease in local (tissue) oxygen levels following microcirculatory hypoperfusion. In contrast, acute reperfusion injury is coupled with an increase in (predominantly) mitochondrial-derived ROS formation (e.g., •O2− and hydrogen peroxide) (7). Elevated levels of ROS may (i) oxidatively modify key protein cysteinyl thiols involved in NO•-dependent vasodilatory signaling; (ii) decrease bioavailable levels of NO• by depleting key cofactors necessary for normal NOS activity (e.g., tetrahydroboipterin [BH4]); and/or (iii) react with NO• to generate other reactive oxidative intermediates, such as ONOO− (80, 92, 149). Thus, it has been hypothesized that NO• derived from iNOS during preconditioning leads to the formation of S-nitrosothiols (and perhaps via acidified NO2− under conditions of extreme acidity, pH≤3), which preserves cardiovascular performance during subsequent time periods of ischemia by protecting functional cysteinyl thiols from ROS-induced oxidative modification(s) and minimizing oxygen-free radical-mediated depletion of NO•. This hypothesis assumes, however, that the half-life of S-nitrosothiols is sufficient to accommodate potentially lengthy periods of time between ischemia, and, thus, does not account for the effects of degradation of S-nitrosothiols, which for CysNO may decrease levels by 90% within 120 min, as an example (89).

The introduction of SNO resin-assisted capture- and 2D-DIGE protein screening techniques for the determination of novel S-nitrosylation targets has expanded broadly the range of proteins known to undergo S-nitrosylation in responses to ischemia/reperfusion (77, 82). For example, Lin et al. used 2D-DIGE methodologies to demonstrate that compared to control, stimulation of eNOS with a selective estrogen receptor-β (ER-β) agonist or 17β-estradiol induced de novo S-nitrosylation of 11 proteins present in the hearts of ovariectomized mice following ischemia/reperfusion injury (82, 103). Of the proteins found to undergo ER-β receptor-dependent S-nitrosylation, four were known previously to be associated with the protective effects of ischemic preconditioning in other experimental models: malate dehydrogenase, creatine kinase M-type, heat shock protein (60 kDa), and myosin light chain 1 (131). The precise mechanism(s) by which these proteins and their S-nitroso-derivatives modulate the salutary effects of ischemic preconditioning has not yet been fully determined.

S-Nitrosylation may also affect favorably the function of mitochondrial proteins involved in ROS generation during ischemia/reperfusion. Murray et al. reported findings from a large-scale survey of candidate S-nitrosylated proteins harvested from rat cardiac mitochondria following exposure to GSNO. They described 83 S-nitrosylated cysteine residues on 60 proteins (99), including the reversible S-nitrosylation of mitochondrial complex I, the entry point of electrons into the respiratory chain and the key contributor to the synthesis of ROS in mitochondria (15, 22). S-Nitrosylation of mitochondrial complex I may be protective against reperfusion injury by limiting the generation of oxygen-derived free radicals. Other nonmitochondrial ROS-generating proteins are S-nitrosylated, including the cell membrane-bound NADPH oxidase (NOX) complex subunit p47phox. During ischemia/reperfusion, S-nitrosylation of p47phox is associated with maintaining the cellular redox potential via suppressed NOX-dependent vascular ROS generation (118).

S-Nitrosylation of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) with iNOS-derived NO• is associated with increased synthesis of prostaglandin I2 (an eicosanoid that promotes vasodilation and inhibits platelet aggregation) and myocardial protection following ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. The stimulatory effect of the HMG-coA-reductase inhibitor, atorvastatin, on iNOS activity, COX-2 synthesis, and COX-2 S-nitrosylation has led some investigators to propose S-nitrosylation as a potential mechanism by which statins protect against various forms of vascular injury, including that following ischemia/reperfusion (4).

Congestive heart failure

S-Nitrosylation-induced alterations in L-type Ca2+ channel, ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2), and SERCA2a function have been reported in animal models of congestive heart failure. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice (nNOS−/−) demonstrated decreased S-nitrosylation of L-type Ca2+ channels following myocardial infarction, resulting in increased L-type Ca2+ channel activity and elevated levels of intracellular Ca2+ in ventricular myocytes. Calcium overload as a consequence of decreased S-nitrosylation of L-type Ca2+ channels, in turn, was linked to disturbances of the cardiac membrane potential and potentiation of fatal arrhythmias, such as ventricular fibrillation (13, 131).

Similar to the findings in L-type Ca2+ channels, S-nitrosylation of the RyR2 receptor, which contains 89 free thiols (143), appears protective against sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak that in heart failure is associated with impaired myocardial contractility and electromechanical instability (46). Gonzalez et al. explored the relationship between oxypurinol and RyR2 receptor S-nitrosylation as a mechanism by which to explain the beneficial clinical effects of xanthine oxidase inhibitors observed in clinical studies of patients with congestive heart failure (45). In cardiac myocytes of spontaneously hypertensive rats with dilated cardiomyopathy, decreasing xanthine oxidase-derived •O2− with pharmacologic xanthine oxidase inhibition restored the intracellular nitroso-redox balance, increased levels of S-nitrosylated RyR2, and resulted in the attenuation of RyR2-mediated diastolic Ca2+ leak and improvements in myocardial contractility (46). Conversely, S-nitrosylation may contribute to the pathophysiology of congestive heart failure by inducing a loss of function of myocyte contractile proteins. For example, compared with normal controls, left ventricular biopsy samples from explanted failing human hearts express elevated levels of S-nitrosylated tropomyosin (18). Although the effect of tropomyosin S-nitrosylation on actomyosin ATPase function has not been fully characterized, these observational data raise speculation that S-nitrosylation of tropomyosin may modulate the adverse downstream actions of iNOS-derived NO• on myocyte contractility that has been observed previously in certain animal models of coronary ischemia (57).

Pulmonary hypertension

S-Nitrosothiols play a regulatory role in the pulmonary vascular response to alterations in blood oxygen levels. Erythrocytes exposed to chronic hypoxia exhibit increased levels of iron-heme nitrosyl, which impairs S-nitrosylation of hemoglobin, is associated with disruption of oxygen-mediated pulmonary vascular relaxation, and promotes the development of pulmonary hypertension (94). Impaired trans-S-nitrosylation is also implicated in the pathobiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension: increased right ventricular systolic pressure and the development of negative pulmonary vascular remodeling is observed in male mice administered N-acetylcysteine in vivo. In this model, maladaptive structural and functional changes to pulmonary blood vessels are linked to the formation of S-nitroso-N-acetylcysteine, which, by scavenging free NO•, limits trans-S-nitrosylation of hemoglobin to decrease levels of S-nitrosohemoglobin (105). Interestingly, female or castrated male mice are protected against the pathological effects of N-acetylcysteine on pulmonary arterial pressure. This observation may reflect the beneficial effects of estrogen (and/or deleterious effect of androgens) on the synthesis of NOS-dependent (vascular protective) S-nitrosothiols prior to treatment with N-acetylcysteine (12).

Cardiac arrhythmias

Nitric oxide and S-nitrosylation of specific cardiomyocyte proteins are at times opposing regulatory determinants of cardiac electrophysiology by virtue of their influence on various phases of the cardiomyocyte action potential. For example, in atrial and ventricular myocytes, NO• promotes activation of the intermediate conductance potassium channel (IK1), the late inward Na+ current (INaL), the slowly activating delayed rectifier current (IKs), and the adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-sensitive K+ channel (IK-ATP) (133). In sinoatrial nodal tissue, NO• exerts a cGMP-dependent stimulatory effect on the pacemaker current (If) that is associated with increases in heart rate (133). S-Nitrosylation of cardiac Na+ SNC5a via nNOS-derived NO• is one mechanism associated with prolongation of the QT interval in the inherited long QT syndrome (LQTS) (i.e., LQTS due to a missense mutation of the SNTA1 gene [A390V-SNTA1]) (138), whereas S-nitrosylation of the IKs channel at Cys445 shortens the cardiac action potential to modulate chronotropic responses to autonomic stimulation (1, 3, 53). In nNOS deficient rats, decreased bioavailable NO• is associated with impaired S-nitrosylation of the voltage-dependent L-type Ca+2 channel that destabilizes the cardiomyocyte membrane potential and decreases the threshold for ventricular arrhythmias (13).

In the sarcoplasmic reticulum, nNOS couples with the ROS generating enzyme xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR), which may serve as an alternate mechanism by which to account for decreased protein S-nitrosylation in the setting of diminished nNOS activity. Specifically, nNOS deficient myocytes demonstrate significantly increased XOR-derived •O2− accumulation, which, in turn, may consume NO•, thereby decreasing levels of the primary substrate for the S-nitrosylation reaction (i.e., NO•) (74).

Nitric oxide is also involved in ion channel-independent mechanisms of cardiac conduction, such as those that involve calcium/calmodulin-dependent calcium ATPase and SERCA (14, 45, 117); however, there are conflicting data on the net effect of S-nitrosylation on ion channel-independent regulatory mechanisms of electrophysiologic stability. In one study, myocytes from genetically engineered iNOS−/− and double iNOS−/−/eNOS−/−, but not eNOS−/−, mice demonstrated decreased S-nitrosylation of the RyR, resulting in diastolic Ca2+ leak and a proarrhythmic substrate (45, 46). In another study involving a murine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy in which elevated levels of iNOS are reported (11), S-nitrosylation of the RyR2 receptor in combination with depletion of the key RyR2 receptor subunit calstabin 2 was mechanistically linked to ventricular arrhythmias (34).

Thrombosis and stroke

Translational studies have defined a clear role for S-nitrosylation in at least three pathobiological aspects of thrombosis and associated brain injury: platelet aggregation, MMP-dependent neurodegeneration, and neurotransmitter-mediated response(s) to cerebrovascular injury. As discussed earlier, NO•-dependent inhibition of platelet activation and aggregation by S-nitrosothiols (S-NO-N-acetyl-cysteine and GSNO) is among the original observations to suggest the antithrombotic potential of S-nitrosylation (128). Work from Lowenstein and colleagues developed this observation further to demonstrate that exposure of human platelets to the NO• donor diethylamine NONOate results in S-nitrosylation of NSF, which inhibits NSF attachment receptors, thereby blocking the release of platelet granules (e.g., ATP, ADP, serotonin) responsible for inducing platelet recruitment and subsequent thrombosis (97). S-Nitrosylation of NSF at Cys91 and Cys264 in vascular endothelial cells is likewise associated with inhibition of Weibel-Palade body exocytosis, a process that otherwise promotes vascular inflammation and thrombosis (93).

In the brain, MMPs promote pathologic extracellular matrix remodeling. During cerebral ischemia, nNOS-dependent NO• synthesis is associated with S-nitrosylation-mediated activation of MMP-9 that induces neuronal apoptosis and promotes neuronal tissue injury (50, 87). Interestingly, ischemia-mediated S-nitrosylation of MMP-9 is reversible, with the S-NO-derivative serving as a cysteinyl thiol reactive intermediate. Further, cysteinyl thiol oxidation of the S-nitrosylated thiol results in the formation of higher cysteinyl thiol oxidative species, including sulfinic acid (-SO2H) and sulfonic acid (-SO3H), that are ultimately responsible for the pathophysiological activation of MMP-9 (125). S-nitrosylation of presynaptic proteins is also implicated in poststroke changes to neuronal function. By inhibiting vesicular glutamate release that induces long-term inhibition of synaptic signal transmission (113), abnormal trans-synaptic signaling occurs and is a contributing factor to neuronal injury following cerebrovascular infarction.

Summary

Cumulative studies in the field of S-nitrosoproteins in the past two decades have established that: (i) S-nitrosylation influences the activity of proteins involved in cardiovascular (patho)physiology; (ii) S-nitrosylation, denitrosylation, and trans-S-nitrosylation are interrelated biochemical reactions that modulate the functional consequences of NO•-cysteine interactions; and (iii) the potential roles for S-nitrosothiols in the pharmacotherapy of cardiovascular diseases remains not yet fully realized. Novel experimental techniques, including contemporary permutations of the biotin-switch method, LC-MS technology, and 2D DIGE analysis, have afforded proteome-wide assessments of S-nitrosoprotein formation in vascular tissue. These advances have significantly expanded the breadth of known protein cysteinyl thiols targeted for the synthesis of their S-nitroso-counterparts.

In the future, the number of clinical studies designed to test S-nitrosothiol-based treatments in patients with cardiovascular diseases will likely increase, particularly in populations with essential hypertension, sickle cell anemia, and pulmonary hypertension. The success of these endeavors, however, is likely to hinge on a more complete understanding of S-nitrosothiol biochemistry to predict better the downstream effects of S-nitrosothiols on fundamental elements of cardiovascular physiology, particularly vascular reactivity, myocyte contractility, and cardiac conduction.

Abbreviations Used

- ADP

adenosine diphosphate

- Ang I

angiotensin I

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- BH4

tetrahydrobiopterin

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- cGMP

cyclic guanosine monophosphate

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- CyDye

cyanide dye-labeling

- Cys

cysteine

- cysTMT

cysteine mass tag

- DIGE

difference gel electrophoresis

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- ER

estrogen receptor

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- FiO2

fraction of inspired O2

- GSH

reduced glutathione

- GSNO

S-nitrosoglutathione

- GSNOR

S-nitroso-glutathione reductase

- GTP

guanosine triphosphate

- HNO2

nitrous acid

- HPDP

N-[6-(biotinamido)hexyl]-3′-(2′-pyridyldithio)propionamide

- HSA

human serum albumin

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

- LQTS

long QT syndrome

- MALDI

matrix-assisted laser desorption

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- MMTS

methyl-methanethiosulfonate

- N2O3

nitrogen trioxide

- NADH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- nNOS

neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- NO•

nitric oxide

- NO+

nitrosonium

- NO2−

nitrite

- NO3−

nitrate

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- NOX

NADPH oxidase

- NSF

N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor

- •O2−

superoxide

- ONOO−

peroxynitrite

- PDI

protein disulfide isomerase

- PKG

protein kinase G

- ReTOF

ionization reflection time-of-flight

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- Se

selenium

- sGC

soluble guanylyl cyclase

- SNAP

S-nitroso-N-acetyl-D,L-penicillamine

- SNO-Hb

S-nitrosylated hemoglobin

- SNO-SA

S-nitroso-serum albumin

- TrxR

thioredoxin reductase

- XOR

xanthine oxidoreductase

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants HL61795, HL70819, HL048743, HL108630, and HL107192 (J.L.). We gratefully acknowledge Stephanie Tribuna for assistance in the preparation of this article.

References

- 1.Abi-Gerges N. Szabo G. Otero AS. Fischmeister R. Mery PF. NO donors potentiate the beta-adrenergic stimulation of I(Ca,L) and the muscarinic activation of I(K,ACh) in rat cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 2002;540:411–424. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abu-Soud HM. Feldman PL. Clark P. Stuehr DJ. Electron transfer in the nitric-oxide synthases. Characterization of L-arginine analogs that block heme iron reduction. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32318–32326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asada K. Kurokawa J. Furukawa T. Redox- and calmodulin-dependent S-nitrosylation of the KCNQ1 channel. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6014–6020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807158200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atar S. Ye Y. Lin Y. Freeberg SY. Nishi SP. Rosanio S. Huang MH. Uretsky BF. Perez-Polo JR. Birnbaum Y. Atorvastatin-induced cardioprotection is mediated by increasing inducible nitric oxide synthase and consequent S-nitrosylation of cyclooxygenase-2. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H1960–H1968. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01137.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baba SP. Wetzelberger K. Hoetker JD. Bhatnagar A. Post-translational glutathiolation of aldose reductase (AKR1B1): a possible mechanism of protein recovery from S-nitrosylation. Chem Biol Interact. 2009;178:250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker K. Savvides SN. Keese M. Schirmer RH. Karplus PA. Enzyme inactivation through sulfhydryl oxidation by physiologic NO-carriers. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:267–271. doi: 10.1038/nsb0498-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beckman JS. Beckman TW. Chen J. Marshall PA. Freeman BA. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:1620–1624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell SE. Shah CM. Gordge MP. Protein disulfide-isomerase mediates delivery of nitric oxide redox derivatives into platelets. Biochem J. 2007;403:283–288. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benhar M. Forrester MT. Hess DT. Stamler JS. Regulated protein denitrosylation by cytosolic and mitochondrial thioredoxins. Science. 2008;320:1050–1054. doi: 10.1126/science.1158265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benhar M. Forrester MT. Stamler JS. Protein denitrosylation: enzymatic mechanisms and cellular functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrm2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bia BL. Cassidy PJ. Young ME. Rafael JA. Leighton B. Davies KE. Radda GK. Clarke K. Decreased myocardial nNOS, increased iNOS and abnormal ECGs in mouse models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31:1857–1862. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown-Steinke K. deRonde K. Yemen S. Palmer LA. Gender differences in S-nitrosoglutathione reductase activity in the lung. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burger DE. Lu X. Lei M. Xiang FL. Hammoud L. Jiang M. Wang H. Jones DL. Sims SM. Feng Q. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase protects against myocardial infarction-induced ventricular arrhythmia and mortality in mice. Circulation. 2009;120:1345–1354. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.846402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burkard N. Williams T. Czolbe M. Blomer N. Panther F. Link M. Fraccarollo D. Widder JD. Hu K. Han H. Hofmann U. Frantz S. Nordbeck P. Bulla J. Schuh K. Ritter O. Conditional overexpression of neuronal nitric oxide synthase is cardioprotective in ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation. 2010;122:1588–1603. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.933630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burwell LS. Brookes PS. Mitochondria as a target for the cardioprotective effects of nitric oxide in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:579–599. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butler AR. Flitney FW. Williams DL. NO, nitrosonium ions, nitroxide ions, nitrosothiols and iron-nitrosyls in biology: a chemist's perspective. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995;16:18–22. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)88968-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camerini S. Polci ML. Restuccia U. Usuelli V. Malgaroli A. Bachi A. A novel approach to identify proteins modified by nitric oxide: the HIS-TAG switch method. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:3224–3231. doi: 10.1021/pr0701456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canton M. Menazza S. Sheeran FL. Polverino de Laureto P. Di Lisa F. Pepe S. Oxidation of myofibrillar proteins in human heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;57:300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen SC. Huang B. Liu YC. Shyu KG. Lin PY. Wang DL. Acute hypoxia enhances proteins' S-nitrosylation in endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:1274–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Z. Zhang J. Stamler JS. Identification of the enzymatic mechanism of nitroglycerin bioactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8306–8311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122225199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christen S. Cattin I. Knight I. Winyard PG. Blum JW. Elsasser TH. Plasma S-nitrosothiol status in neonatal calves: ontogenetic associations with tissue-specific S-nitrosylation and nitric oxide synthase. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2007;232:309–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clementi E. Brown GC. Feelisch M. Moncada S. Persistent inhibition of cell respiration by nitric oxide: crucial role of S-nitrosylation of mitochondrial complex I and protective action of glutathione. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7631–7636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Darra E. Rungatscher A. Carcereri de Prati A. Podesser BK. Faggian G. Scarabelli T. Mazzucco A. Hallstrom S. Suzuki H. Dual modulation of nitric oxide production in the heart during ischaemia/reperfusion injury and inflammation. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104:200–206. doi: 10.1160/TH09-08-0554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Franceschi L. Malpeli G. Scarpa A. Janin A. Muchitsch EM. Roncada P. Leboeuf C. Corrocher R. Beuzard Y. Brugnara C. Protective effects of S-nitrosoalbumin on lung injury induced by hypoxia-reoxygenation in mouse model of sickle cell disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L457–L465. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00462.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doulias PT. Greene JL. Greco TM. Tenopoulou M. Seeholzer SH. Dunbrack RL. Ischiropoulos H. Structural profiling of endogenous S-nitrosocysteine residues reveals unique features that accommodate diverse mechanisms for protein S-nitrosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16958–16963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008036107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doyle MP. Hoekstra JW. Oxidation of nitrogen oxides by bound dioxygen in hemoproteins. J Inorg Biochem. 1981;14:351–358. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)80291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dudzinski DM. Igarashi J. Greif D. Michel T. The regulation and pharmacology of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;46:235–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dulce RA. Gonzalez DR. Treuer AV. Hare JM. Hydrazaline-nitroglycerin combination reduces diastaolic calcium leak in adult cardiomyocytes from nitric oxide synthase-1-deficient mice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:A25. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eisen A. Fisman EZ. Rubenfire M. Freimark D. McKechnie R. Tenenbaum A. Motro M. Adler Y. Ischemic preconditioning: nearly two decades of research. A comprehensive review. Atherosclerosis. 2004;172:201–210. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(03)00238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elviri L. Speroni F. Careri M. Mangia A. di Toppi LS. Zottini M. Identification of in vivo nitrosylated phytochelatins in Arabidopsis thaliana cells by liquid chromatography-direct electrospray-linear ion trap-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2010;1217:4120–4126. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erwin PA. Lin AJ. Golan DE. Michel T. Receptor-regulated dynamic S-nitrosylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19888–19894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413058200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erwin PA. Mitchell DA. Sartoretto J. Marletta MA. Michel T. Subcellular targeting and differential S-nitrosylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:151–157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510421200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Espey MG. Thomas DD. Miranda KM. Wink DA. Focusing of nitric oxide mediated nitrosation and oxidative nitrosylation as a consequence of reaction with superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11127–11132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152157599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]