Abstract

The extracellular heme-thiolate peroxygenase from Agrocybe aegerita (AaeAPO) has been shown to hydroxylate alkanes and numerous other substrates using hydrogen peroxide as the terminal oxidant. We describe the kinetics of formation and decomposition of AaeAPO compound I upon its reaction with mCPBA. The UV–vis spectral features of AaeAPO–I (361, 694 nm) are similar to those of chloroperoxidase–I and the recently–described cytochrome P450–I. The second–order rate constant for AaeAPO–I formation was 1.0 (±0.4) ×107 M−1s−1 at pH 5.0, 4 °C. The relatively slow decomposition rate, 1.4 (±0.03) s−1, allowed the measurement of its reactivity toward a panel of substrates. The observed rate constants, k2’, spanned five orders of magnitude and correlated linearly with bond dissociation enthalpies of strong C–H bond substrates with a log k2’ vs. BDE slope of ~ 0.4. However, the hydroxylation rate was insensitive to C–H BDE below 90 kcal/mol, similar to the behavior of the t-butoxy radical. The shape and slope of the Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi plot indicate a symmetrical transition state for the stronger C–H bonds and suggest entropy control of the rate in an early transition state for weaker C–H bonds. The AaeAPO–II FeIVO–H BDE was estimated to be ~ 103 kcal/mol. All results support the formation of a highly reactive AaeAPO oxoiron(IV) porphyrin radical cation intermediate that is the active oxygen species in these hydroxylation reactions.

The fungal peroxygenase AaeAPO (EC 1.11.2.1) from Agrocybe aegerita is a new and highly active heme-thiolate protein.1 It catalyzes a wide range of H2O2–dependent oxidations including alkane and arene hydroxylations, epoxidations, halogenations and ether cleavage reactions.2 AaeAPO functions as a monooxygenase, similar to cytochrome P450, and has been shown to produce human metabolites efficiently from drugs.3 However, it has no significant sequence homology to P450s and shares only a 30% similarity with chloroperoxidase (CPO).4 The active site of AaeAPO contains a glutamic acid and an arginine near the distal side of the heme,5 rather than the highly conserved threonine found within P450s.6 The corresponding residues for CPO are glutamate and histidine.7 Another new heme-thiolate hydroxylase, P450 BSβ, lacks the active site glutamate but apparently supplants that with a carboxylate provided by its fatty acid substrate.8 Notably, AaeAPO, CPO and P450 BSβ turn over readily with hydrogen peroxide as a co–substrate, as does a model heme-thiolate system.9 Aside from this similarity and obvious analogies in the substrate reaction profile, little is known about the mechanism of oxygen transfer catalyzed by AaeAPO or the nature of any reactive intermediates in its catalytic cycle.

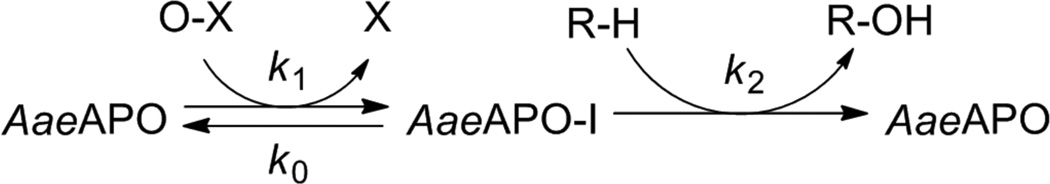

Here, we report the generation and spectral characterization of AaeAPO compound I, formed by the reaction of ferric AaeAPO with m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (mCPBA) (k1). Kinetic measurements of the reactivity of AaeAPO–I using a panel of substrates have revealed very fast C-H hydroxylation rates (k2), similar to those of CYP11910 and the most reactive iron-porphyrin model compounds11 (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

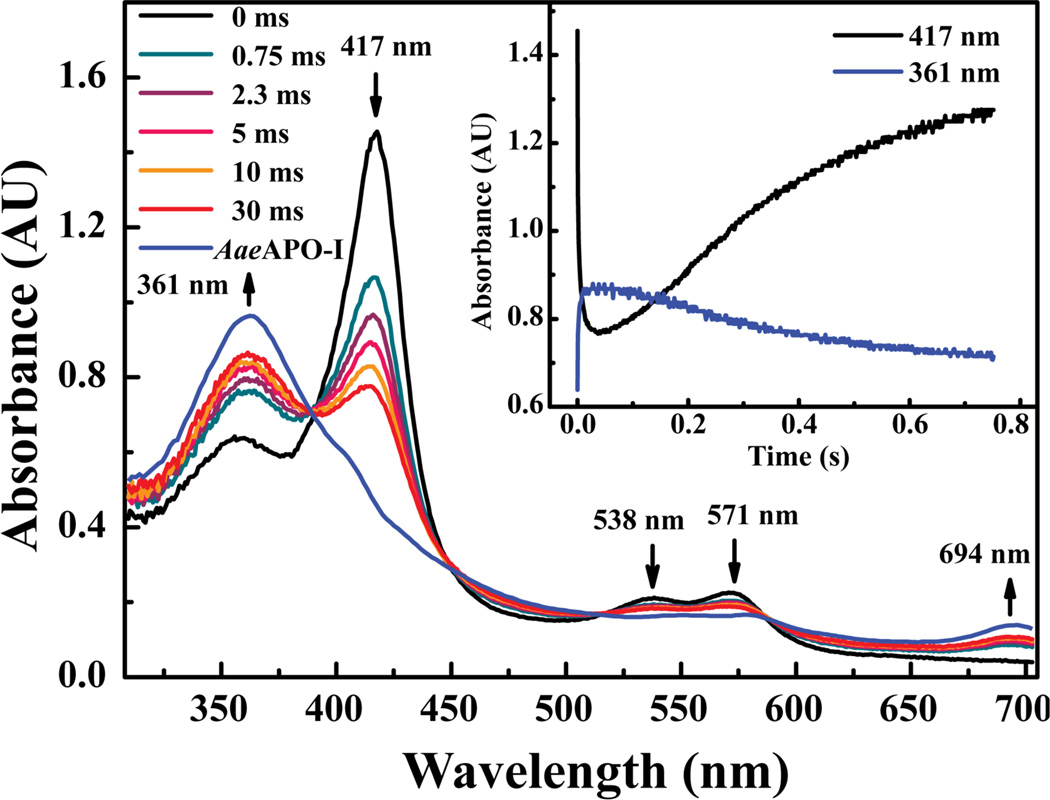

The spectrum of resting AaeAPO displays an intense Soret band at 417 nm and two Q bands at 538 nm and 571 nm (Figure 1). The position of the Soret band indicates that resting ferric AaeAPO is low-spin. Obvious and diagnostic changes in the UV–vis spectrum of ferric AaeAPO upon substrate binding indicated a low–spin to high-spin inter-conversion, typical of cytochrome P450 enzymes.12 Reaction of the ferric enzyme with two equivalents of mCPBA at 4 °C, using rapid-mixing, stopped-flow techniques, generated a short-lived intermediate that displayed a new band at 361 nm and a distinct absorbance at 694 nm. This spectral transient appeared within 30 ms of mixing. The Soret band of the remaining ferric enzyme decreased dramatically during this time. SVD analysis10b and the observation of a clear set of multiple isosbestic points (390 nm, 448 nm, 516 nm and 586 nm) indicated that only two major species were present during this transformation. The weak, blue-shifted Soret band and the absorbance at 694 nm strongly suggest the presence of a porphyrin radical cation species and that the intermediate is AaeAPO compound I. The spectrum of AaeAPO–I, which was obtained by globally fitting the data in Figure 1, recapitulates those of P45010,13 and CPO.14 The deconvolution indicated that AaeAPO–I had been formed in 70% yield. Accordingly, no spectral subtractions were necessary in these analyses.

Figure 1.

UV–vis transients observed upon 1:1 mixing of 13 µM of ferric enzyme with 25 µM of mCPBA at pH 5.0, 4°C. Maximum yield of AaeAPO–I reached 70% at 30 ms. Blue line indicates the spectrum of AaeAPO–I (361 nm) obtained by global analysis.

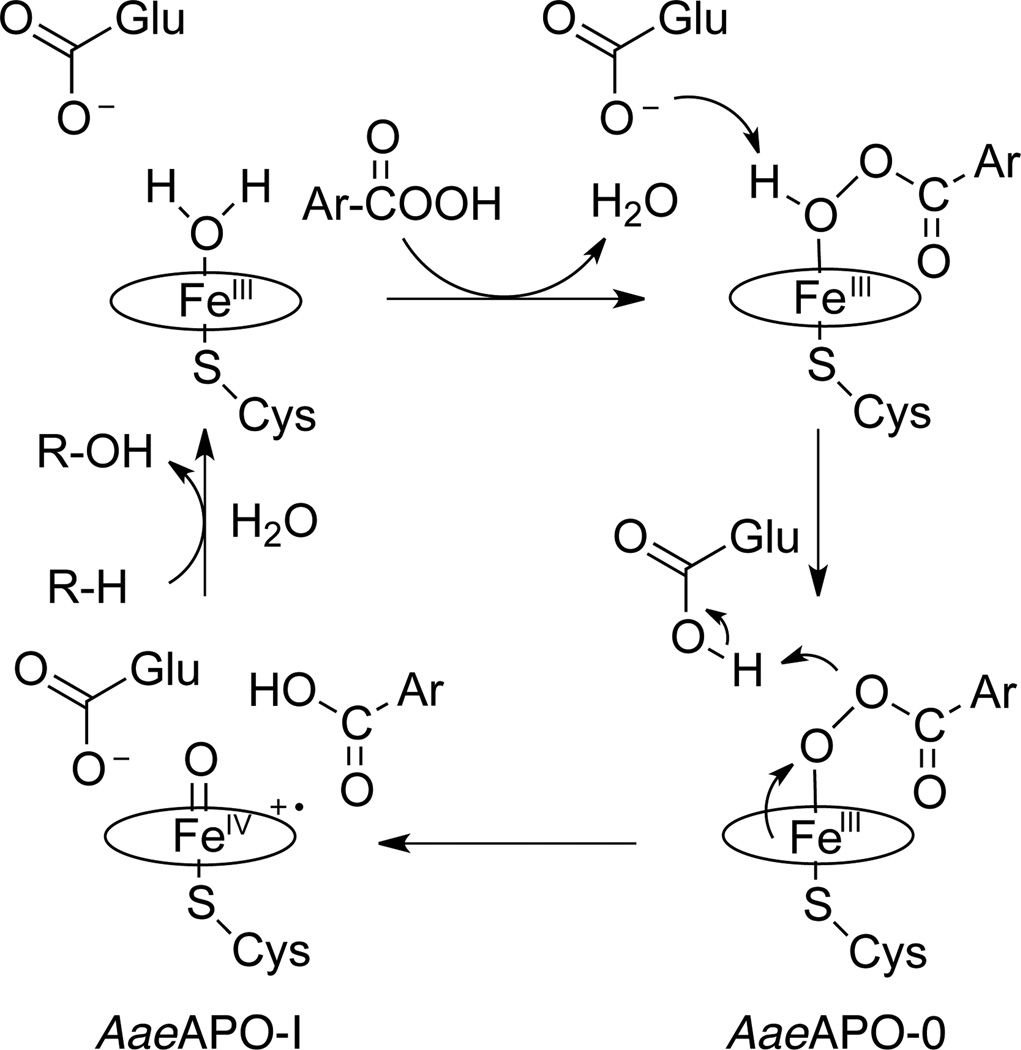

The extent of AaeAPO–I formation and the rate of its subsequent decay were found to be optimal at pH 5.0 (Table 1 and Figure S1). Second-order rate constants for the reaction of AaeAPO with mCPBA were obtained by monitoring the conversion of ferric protein at 417 nm and plotting the single-exponential decay of the ferric enzyme against a range of mCPBA concentrations. Full diode array spectra confirmed that the porphyrin radical cation absorbances at 361 nm and 694 nm grew in and decayed with the same kinetics. The maximal rate constant observed was 1.1 (±0.5) ×107 M−1s−1 at pH 6.0, which is consistent with a reaction of AaeAPO with the protonated form of mCPBA (pKa 7.6).13b It is interesting that the formation rate decreased significantly from pH 5.0 to pH 3.0. AaeAPO is known to have an active site glutamate close to the heme center,4–5 which could play a role in the formation of AaeAPO–I by hydrogen peroxide, apparently its natural co–substrate. Thus, mCPBA would initially replace a distal water ligand in resting AaeAPO with proton transfer to the neighboring glutamate to form an unseen peroxo-adduct, similar to peroxidase compound 0. Subsequently, O–O bond heterolysis and formation of AaeAPO–I would be assisted by proton transfer from the active site glutamate to the product, mCBA, as outlined in Scheme 2. This role for the distal glutamate is similar to that proposed for the substrate carboxylate group in fatty acid hydroxylation by cytochrome P450 BSβ8 and SPα.15

Table 1.

The observed AaeAPO compound I formation and spontaneous decay rate constants, k1 and ko at pH 3–7.

| pH | k1 (M−1s−1) | k0 (s−1) |

|---|---|---|

| 3.0 | 3.4 (±0.1)×106 | 2.5 (±0.03) |

| 4.0 | 5.3 (±0.1)×106 | 3.9 (±0.04) |

| 5.0 | 1.0 (±0.4)×107 | 1.4 (±0.03) |

| 6.0 | 1.1 (±0.5)×107 | 3.1 (±0.03) |

| 7.0 | 9.1 (±0.7)×106 | 4.1 (±0.04) |

Scheme 2.

The rate of AaeAPO–I decay followed first-order kinetics and could be fitted directly from the data in Figure S1. This spontaneous reduction of AaeAPO–I was slowest at pH 5.0, k1 =1.4 (±0.03) s−1. The decay rate is faster than that of CPO–I (0.5 s−1 at pH 4.7, 25 °C)16 but slower than that of CYP119–I (9 s−1, pH 7.0, 4°C).10a,13b While the mechanism of spontaneous decay of compound I is unknown, more than 90% ferric protein was recovered in the process.

As we have recently reported, AaeAPO has a high selectivity for the hydroxylation of saturated hydrocarbons,2b,17 similar to P450 enzymes but in distinct contrast with chloroperoxidase.10a,18 Thus, slow addition of 20 mM H2O2 or peroxyacid to a solution containing 0.22 µM AaeAPO and 10 mM p–ethylbenzoic acid produced (R)-4-(1-hydroxyethyl)benzoic acid in high conversion and 99% ee (Figure S2).17 Subsequent oxidation of the benzylic alcohol product occurred only after all of the p–ethylbenzoic acid had been consumed. Remarkably, AaeAPO was found to hydroxylate a methyl C–H bond in dimethyl butyric acid and even neopentane (BDE ~ 100 kcal/mol) to produce the corresponding primary alcohols.

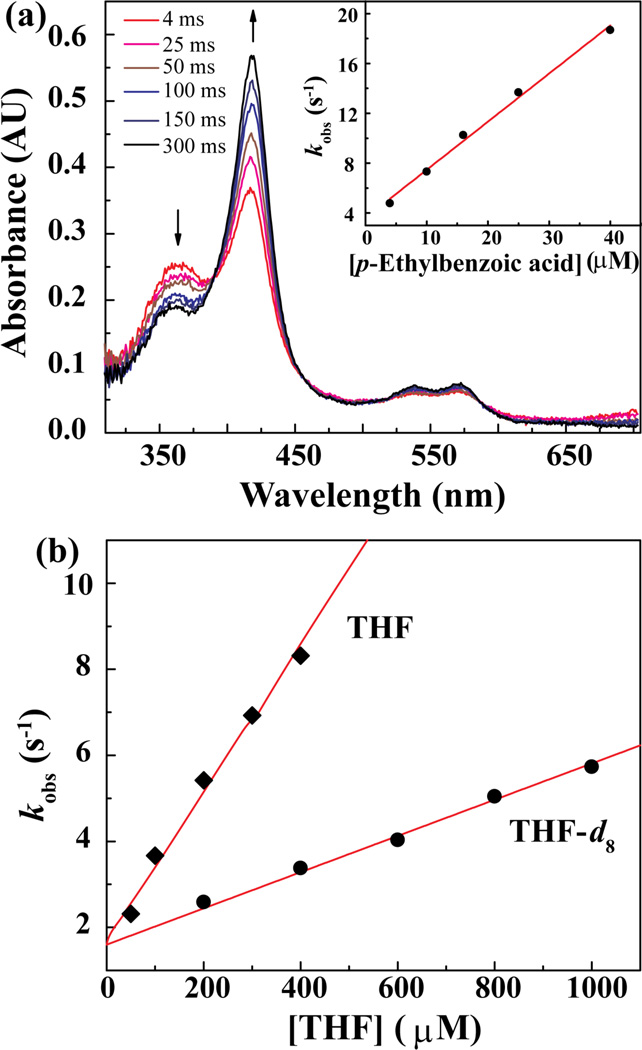

The persistence of AaeAPO–I over nearly a second at pH 5.0 allowed us to measure its reactivity toward a panel of typical aliphatic substrates over a wide range of C–H bond BDE (83–100 kcal/mol). In each case we determined the identity of the products and product ratios under catalytic conditions by comparing NMR and GC–MS data with those of authentic samples. We used double mixing, stopped-flow techniques to monitor the kinetics of the AaeAPO–I reaction with various substrates.11 Figure 2a shows a typical kinetic experiment. At pH 5.0, 4°C, the first mixing generated AaeAPO–I within an aging time of 20 ms. Then, solutions with varying concentrations of each substrate were mixed with AaeAPO–I in the second push. The observed decay rates (kobs) were obtained by fitting the return of the ferric enzyme. Plots of kobs against substrate concentration gave linear relationships as shown in Figure 2a inset and Figure 2b. Lastly, apparent per-hydrogen second-order rate constants, k2’, for the reaction of AaeAPO–I with each substrate were obtained from the observed slopes in the usual manner. As shown in Figure 2b, a kinetic hydrogen isotope effect (kH/kD = 4.3) could also be measured from the ratio of k2 obtained for THF and THF–d8 as substrates. Table S1 lists the rate constants, k2 and k2’, for each of the substrates under study.

Figure 2.

(a) UV–vis spectra obtained during the reaction of 10 µM AaeAPO–I with 16 µM p–ethylbenzoic acid at pH 5.0, 4°C. Inset: Observed first-order decay rates versus p–ethylbenzoic acid concentration. The apparent second-order rate constant, k2, was obtained from the slope. (b) Observed first–order decay rates versus concentrations of THF or THF–d8. A KIE of 4.3 for THF and THF–d8 was determined from the ratio of the slopes.

It is of interest to compare the reactivity of AaeAPO–I observed here to those of CYP119 compound I, recently reported by Rittle and Green10a, CPO compound I reported by Newcomb et al.18b and the reactive model oxoiron(IV) porphyrin radical cation species, [O=FeIV-4-TMPyP]+, we have recently described.11 Further, it is instructive to consider these comparisons in light of insights derived from computational approaches.19 The rate constant observed for benzylic C–H hydroxylation of ethylbenzoic acid by AaeAPO–I is 125–fold faster than that observed for our model compound I ferryl porphyrin at 10 °C and 250 times faster than those of CPO–I with similar substrates at 22 °C. For CYP119 compound I, rate constants of 103 – 107 M−1s−1 have been reported for unactivated methylene groups of fatty acids.10a The slower of these rates, which are for hexanoic and octanoic acid, are similar to those observed here for AaeAPO–I, while the fastest rate constant for CYP119 was for lauric acid, a tight-binding substrate, and may be an irreversible binding event.

We note that even the fastest C–H hydroxylation reactions found here for AaeAPO-I are still more than an order of magnitude slower than the rate of oxidation of the ferric protein by mCPBA. Similarly, the low-spin to high-spin transition upon substrate binding was found to be very fast (>2×106 M−1s−1). Thus, the rate of substrate access to the active site is significantly faster than the rate of reaction and, accordingly, the observed rates are likely to be measures of the intrinsic C–H reactivity toward AaeAPO–I. Consistent with this expectation, the active site of AaeAPO has a shallow, hydrophobic substrate-binding cavity flanked by several phenylalanine residues.5 Further evidence for fast, reversible substrate binding is the observation of the intermolecular isotope effect (kH/kD) of 4.3 for THF and THF–d8.

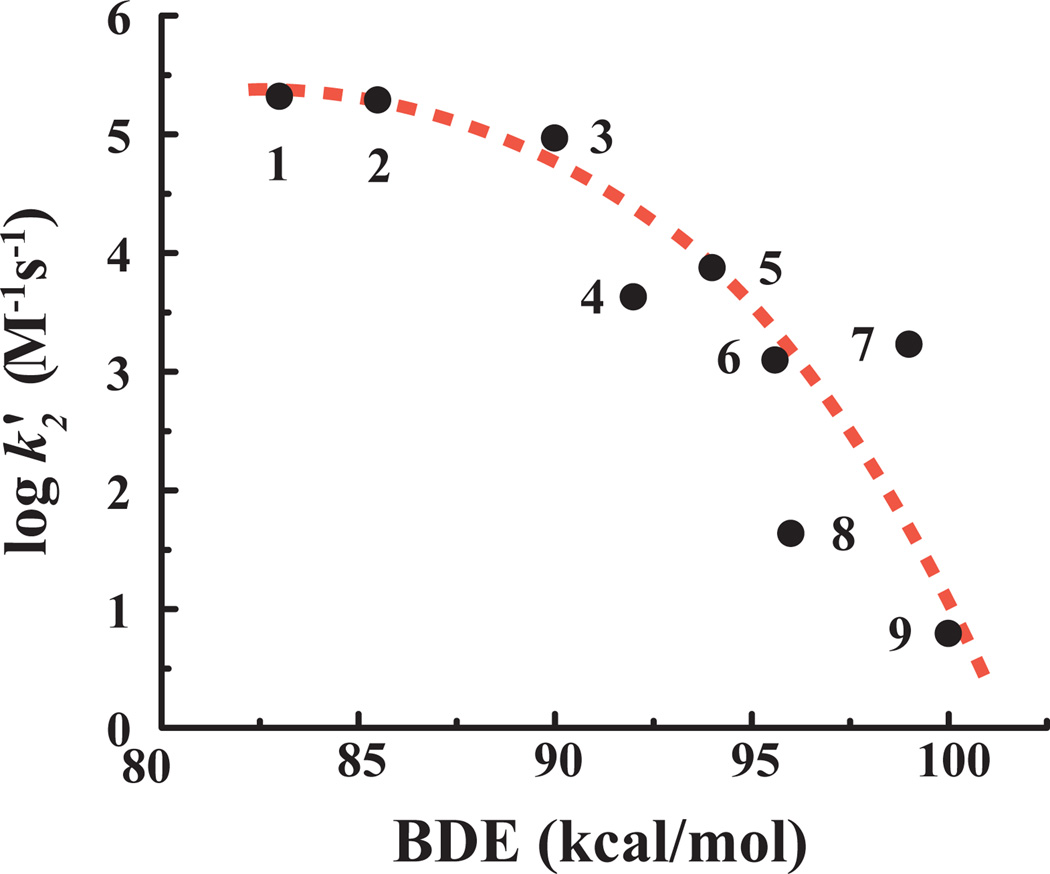

A plot of second-order rate constants for C–H hydroxylation by AaeAPO–I for all substrates vs. BDE of the scissile C–H bond revealed a very distinct, non-linear correlation (Figure 3). Notably, there was almost no change in k2’ for the substrates with C–H BDE less than 90 kcal/mole. By contrast, the slope of log k2’ vs. BDE above 90 kcal/mole was ~ 0.4. Based on the Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi (BEP) relationship: log(kH) = αΔHo + c, where ΔHo is related to the C–H BDE and α is a measure of transition state location. An α of 0.4 for the stronger C–H bonds indicates that these hydrocarbon hydroxylations mediated by AaeAPO–I have a nearly symmetrical [FeO---H---C] transition state. We recently reported a linear BEP relationship for a model compound I with a series of C–H substrates.11 The observed log k vs BDE plot was rather flat (α = 0.28) in that case, intermediate between the high and low values observed for AaeAPO–I (Figure 3). For the model system we estimated the intermediate compound–II FeIVO–H BDE to be ~ 100 kcal/mol. The reaction of AaeAPO–I with ethylbenzoic acid is much faster than that of our model system. Mapping the results for AaeAPO–I with ethylbenzoic acid and toluic acid onto the plot correlating log k(H) with O–H bond strength20, we found that the rate constants were only slightly slower than those of t-butoxyl radical (t-BuO–H BDE 105 kcal/mol21). Accordingly, we estimate that the FeIVO–H BDE for AaeAPO–II to be ~103 kcal/mol (Figure S3), larger than the value of 98 kcal/mol that has been estimated for the FeIVO–H BDE of CPO compound II.22

Figure 3.

Plot of log k2’ vs. substrate C–H BDE, compound numbers are from Table S1.

As can be seen in Figure 3, the two ether substrates, THF and dioxane, were found to be significantly less reactive than predicted by their C–H BDE (points 4 and 8, respectively). We ascribe this deviation to the more hydrophilic nature of these substrates and a polar effect19b,23 due to the neighboring oxygen. Competitive KIEs were also carried out under turnover conditions between dioxane and dioxane-d8, affording a KIE of 12, consistent with the stronger C–H bond and, accordingly, a more symmetrical transition state [Fe-O---H---C]‡. Cyclohexane carboxylic acid (point 6), by contrast, was found to be ~30–fold more reactive than predicted by the trend line. This anomaly, which has also been observed for six-membered rings with synthetic oxometalloporphyrins,24 may be attributed to eclipsing strain relief in the chair-like transition state for hydrogen abstraction for that substrate.25 The intermolecular KIE for cyclohexane and cyclohexane-d12 hydroxylation by AaeAPO was found to be 3.

The insensitivity of the reaction rate to the strength of the C–H bond in the region of BDE below 90 kcal/mol is worth further comment. Nearly identical behavior, including the change of slope near 90 kcal/mol, has been reported by Tanko et al. for hydrogen abstraction from a variety of substrates by the t-butoxyl radical, which has been suggested to be a model of P450 reactivity.21,26 Since the fastest rates observed for AaeAPO–I are slower than substrate exchange at the active site and certainly much slower than the diffusion limit, neither of these effects are likely explanations of the insensitivity of the rate to BDE. However, as with the t-butoxyl radical, an early transition state for weaker C–H bonds and the anticipated small activation enthalpy, suggest that the hydroxylation of these weaker C–H bonds by AaeAPO–I may be in the regime of entropy control in which TΔS‡ > ΔH‡.21 In such a case, the AaeAPO–I intermediate is so reactive that rates of hydrogen abstraction are governed more by factors such as accessibility, orientation and trajectory toward the highly ordered substrate–like transition state.

In summary, our study of AaeAPO supports the formation of a highly reactive AaeAPO oxoiron(IV) porphyrin radical cation intermediate. Reaction kinetics for AaeAPO–I with a variety of substrates have revealed an informative correlation between the C–H BDE and the observed bimolecular rate constants. The large estimated FeIVO–H BDE of 103 kcal/mol for AaeAPO–II is significant with regard to its relationship to the pKa of AaeAPO–II and the one-electron reduction potential of AaeAPO–I. These aspects are under investigation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for support of this research by the National Institutes of Health (2R37 GM036298 to jtg). A portion of this work was supported by the European Social Fund, project number 080935557, and the European Union integrated project, Peroxicat, project number 265397.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information.

Materials, instrumentation, reaction kinetics, absorption traces, water suppressed 1H-NMR spectrum and kinetics data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hofrichter M, Ullrich R, Pecyna MJ, Liers C, Lundell T. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;87:871. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2633-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Kinne M, Poraj-Kobielska M, Ralph SA, Ullrich R, Hofrichter M, Hammel KE. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:29343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.040857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Peter S, Kinne M, Wang X, Ullrich R, Kayser G, Groves JT, Hofrichter M. FEBS J. 2011;278:3667. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poraj-Kobielska M, Kinne M, Ullrich R, Scheibner K, Kayser G, Hammel KE, Hofrichter M. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011;82:789. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pecyna MJ, Ullrich R, Bittner B, Clemens A, Scheibner K, Schubert R, Hofrichter M. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009;84:885. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2000-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Piontek K, Ullrich R, Liers C, Diederichs K, Plattner DA, Hofrichter M. Acta Crystallographica Section F. 2010;66:693. doi: 10.1107/S1744309110013515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kinne M. PhD Thesis. Zittau, Germany: International Graduate School; 2010. p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlichting I, Berendzen J, Chu K, Stock AM, Maves SA, Benson DE, Sweet BM, Ringe D, Petsko GA, Sligar SG. Science. 2000;287:1615. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Sundaramoorthy M, Terner J, Poulos TL. Structure. 1995;3:1367. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00274-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sundaramoorthy M, Terner J, Poulos TL. Chem. Biol. 1998;5:461. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Lee DS, Yamada A, Sugimoto H, Matsunaga I, Ogura H, Ichihara K, Adachi S, Park SY, Shiro Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:9761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211575200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shoji O, Fujishiro T, Nakajima H, Kim M, Nagano S, Shiro Y, Watanabe Y. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:3656. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang Z, Breslow R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:5463. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.08.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Rittle J, Green MT. Science. 2010;330:933. doi: 10.1126/science.1193478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rittle J, Younker JM, Green MT. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:3610. doi: 10.1021/ic902062d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell SR, Groves JT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9640. doi: 10.1021/ja903394s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isin EM, Guengerich FP. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008;392:1019. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2244-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Egawa T, Shimada H, Ishimura Y. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994;201:1464. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kellner DG, Hung SC, Weiss KE, Sligar SG. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:9641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100745200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Spolitak T, Dawson JH, Ballou DP. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:20300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Egawa T, Proshlyakov DA, Miki H, Makino R, Ogura T, Kitagawa T, Ishimura Y. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2001;6:46. doi: 10.1007/s007750000181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Palcic MM, Rutter R, Araiso T, Hager LP, Dunford HB. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1980;94:1123. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)90535-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujishiro T, Shoji O, Nagano S, Sugimoto H, Shiro Y, Watanabe Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:29941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.245225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Araiso T, Rutter R, Palcic MM, Hager LP, Dunford HB. Can. J. Biochem. 1981;59:233. doi: 10.1139/o81-031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kluge M, Ullrich R, Scheibner K, Hofrichter M. Green Chem. 2012;14:440. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Zaks A, Dodds DR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:10419. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang R, Nagraj N, Lansakara DSP, Hager LP, Newcomb M. Org. Lett. 2006;8:2731. doi: 10.1021/ol060762k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Lai W, Li C, Chen H, Shaik S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:5556. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shaik S, Cohen S, Wang Y, Chen H, Kumar D, Thiel W. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:949. doi: 10.1021/cr900121s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Klinker EJ, Shaik S, Hirao H, Que L., Jr Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:1291. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayer JM. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998;31:441. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finn M, Friedline R, Suleman NK, Wohl CJ, Tanko JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:7578. doi: 10.1021/ja0493493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green MT, Dawson JH, Gray HB. Science. 2004;304:1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1096897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Shaik S, Kumar D, de Visser SP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:14016. doi: 10.1021/ja8019615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shaik S, Lai WZ, Chen H, Wang Y. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010;43:1154. doi: 10.1021/ar100038u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu W, Groves JT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12847. doi: 10.1021/ja105548x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen K, Eschenmoser A, Baran PS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:9705. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanko JM, Friedline R, Suleman NK, Castagnoli N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5808. doi: 10.1021/ja005730l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.