Abstract

Background

Lung transplantation provides a viable option for survival of end-stage respiratory disease. In addition to prolonging survival, there is considerable interest in improving patient-related outcomes such as transplant recipients’ symptom experiences.

Methods

A prospective, repeated measures design was used to describe the symptom experience of 85 lung transplant recipients between 2000–2005. The Transplant Symptom Inventory (TSI) was administered before and at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months post-transplant. Ridit analysis provided a unique method for describing symptom experiences and changes.

Results

After lung transplantation, significant (p<.05) improvements were reported for the most frequently occurring and most distressing pre-transplant symptoms (e.g., shortness of breath with activity). Marked increases in the frequency and distress of new symptoms, such as tremors were also reported. Patterns of symptom frequency and distress varied with the time since transplant.

Conclusion

The findings provide data-based information that can be used to inform pre- and post-transplant patient education and also help caregivers anticipate a general time frame for symptom changes in order to prevent or minimize symptoms and their associated distress. In addition, symptoms are described, using an innovative method of illustration which shows “at-a-glance” changes or lack of changes in patients’ symptoms from pre- to post-lung transplant.

Keywords: symptoms, symptom experience, lung transplant, transplant candidates, transplant recipients

Introduction

Lung transplantation can prolong and improve the quality of life of patients with severe pulmonary disease when alternative treatment options are no longer effective. Over the past two decades there has been remarkable improvement in short-term survival rates for lung transplant (LTx) patients (83.8% 1-year survival) due to decreased early graft failure (1, 2). In addition to survival, there is considerable interest in examining patient-related outcomes of solid organ transplantation such as the symptom experience of the recipient. Symptoms are critically important to patients because they use symptoms to monitor changes in their health (3). Studies have shown that undesirable symptom experiences negatively affect organ transplant recipients’ quality of life (4, 5–7). Yet, only a few studies have investigated the symptom experiences of organ transplant patients, especially LTx recipients.

Symptoms are subjective perceptions of change in usual functioning, sensations, or feelings that an individual experiences and believes to be indicative of an illness or disorder (8). In progressive disease conditions, such as end-stage respiratory illness, symptoms can grow in frequency and severity until they cause severe, psychological and/or physical distress. Respiratory symptoms, such as shortness of breath (SOB) at rest or with activity, are known to be among the most distressing symptoms experienced in end-stage respiratory patients who are candidates for lung transplantation (9, 10). Symptom assessment tools offer the ability to measure symptom experience at a point in time and often address two related but different concepts: symptom occurrence (frequency) and symptom distress (i.e., emotional response) (3, 7, 11–19). While symptom distress provides the most information about the impact of symptoms on quality of life, combining measurements of symptom distress and symptom frequency increases the information obtained (20). Changes occurring in the pre- to post-LTx symptom experiences have not been well documented (3, 6, 7, 15, 17, 21). A greater understanding of LTx patients’ patterns of symptom experiences over time is important in order to fully inform and educate LTx patients and to engage patients (and their families) in symptom monitoring and management. Furthermore, identification of symptoms and their pattern of change over time are crucial in order to develop and plan effective symptom prevention and/or management strategies for this patient population. This study is unique in that it uses a longitudinal design and prospectively examined 85 LTx patients’ symptom experiences before and during their first year post-LTx.

The purposes of this study were to describe patients’ symptom experiences before and at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after lung transplantation by: 1) identifying the top 10 symptoms reported to be most frequently occurring and/or distressing pre-transplant, 2) examining changes in symptom frequency and distress from pre-transplant to up to one year after lung transplantation, and 3) developing an innovative method to clearly display symptom frequency and symptom distress patterns of change.

Method

This study used a longitudinal, repeated measures design. It was part of a larger project which examined predictors of LTx patients’ quality of life one year post-LTx. All LTx candidates who met the study criteria for two university medical centers’ LTx programs (one in Illinois [2000–2005] and the other in Wisconsin [2004–2005]) were invited to participate. The second study site was added in order to increase subject recruitment and obtain the sample size needed to meet one of the purposes of the parent study). Study subjects had to be: 1) 18–64 years of age; 2) sign an informed consent; and 3) able to read and understand English. Patients who had undergone previous LTx or who were scheduled for heart-lung transplantation were excluded.

Procedure

After Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was received, letters describing the study were sent to eligible LTx candidates. Interested patients were met at their next LTx clinic visit and after they signed an informed consent, data collection began. The Transplant Symptom Inventory (TSI) was administered every 3 months until transplant and at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after transplant. Demographic and clinical data were collected from subjects’ medical records. The 3-month data collection interval was chosen because most LTx candidates and recipients were seen in clinic approximately every 3 months and this data collection frequency would provide an opportunity to identify if a pattern of symptom change exists as well as describe the changes. For this study, the TSI completed closest to and prior to the transplant date was used as the baseline to which post-transplant comparisons were made. The actual median time between the pre-transplant questionnaire completion and transplantation was 45 days with a mean of 63 days ± SD 71 days (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Lung Transplant Subjects’ Characteristics

| Variables | 85 Recipients Followed Pre to Post Lung Transplant | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Gender | Female | 49 (57.6) |

| Male | 36 (42.4) | |

|

| ||

| Race | White | 68 (80) |

| Hispanic | 9 (10.6) | |

| African American | 8 (9.4) | |

|

| ||

| Underlying Respiratory | Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis | 24 (28.2) |

| Diagnosis | Emphysema | 18 (21.2) |

| Alpha1 Deficiency | 12 (14.1) | |

| Cystic Fibrosis | 14 (16.5) | |

| Other | 17(20) | |

|

| ||

| Type of Transplant | Bilateral, Sequential | 50 (58.8) |

| Single Lung | 35 (41.2) | |

|

| ||

| Age * M±SD | 46.2 yrs ± 12.6 yrs | |

|

| ||

| Transplant List Wait Time (Days) | 481 ± 369 days (Median = 325) | |

|

| ||

| Time from Last Pre-transplant Data Collection to Transplant Date | 62 ± 68 days (Median = 45) | |

M±SD = Mean ± Standard Deviation

Transplant Symptom Inventory

At the time of the implementation of this study (2000), the only tools focusing entirely on transplant patients’ symptoms were developed for heart transplant patients, ranging from 29 items (13) to 92 items (13, 14, 16). A symptom list that was more relevant to LTx patients was needed. Thus, the investigators (see acknowledgement) developed the Transplant Symptom Inventory (TSI), which lists 64 symptoms identified as relevant to patients before and after LTx. The TSI measures symptom frequency and distress. Using a 5-point Likert-scale, subjects rate how frequently each symptom occurs from 0 (never) to 4 (always and then rate how distressing each symptom is from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The TSI questionnaire was administered every three months (once the subjects’ participation in the study started) and the timeframe for recalling their symptoms was since their last completion of the TSI. An open-ended question at the end of the instrument provides an opportunity for patients to add any symptom they experienced not addressed in the TSI symptom list. The content validity of the TSI is based on clinical experience, our previous work (15), the literature, and a national panel of five experts consisting of three advanced nurse practitioners and two physicians working in the area of lung transplantation. Cronbach alpha was .912 for symptom frequency and .962 for symptom distress. The focus of this report is the specificity and patterns of symptom changes over time.

Analyses

Descriptive and inferential statistics were used for the demographic and symptom data. Since the symptom frequency and distress data were ordinal data, we used an analysis method called ridit (i.e., relative to an identified distribution) (22). Ridit analysis has been used to investigate symptoms in heart (23), renal (3,24, 25), liver (12), and LTx recipients (3). In this study, the pre-LTx symptom frequency and distress scores were the identified reference distribution for comparison. Ridit measures the relative probability that a randomly selected patient from the comparison group (post-LTx) has a value indicating either greater or lesser severity than a randomly selected patient from the reference group (pre-LTx), thus providing useful information for clinical interpretation (26). The resulting ridit score represents a probability that ranges from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 1. If the mean ridit for a comparison group (post-LTx) is greater than .50, then more than half of the time a randomly selected post-transplant patient will have a more extreme value for the measured symptom than a randomly selected pre-transplant patient in the reference group and vice versa (25). Mean ridit difference scores for each post-LTx symptom was used to assess symptom change. Our reported symptom change measures are based on a d-family (i.e., standardized effect size of group differences) (27, 28). The ridit effect size based on differences per symptom was used to determine the magnitude and direction of post-transplant symptom change from the pre-transplant mean. To address the probability of Type I error due to multiple testing, we used the False Discovery Rate (FDR) method (29) which adjusted our probability decisions at each time period. False discovery rate (FDR) is a statistical method commonly used to correct for multiple comparisons which is more liberal than the Bonferroni correction and more powerful than the familywise error rate (FWER) correction method (29,30). Statistical significance was set at p <0.05.

Results

Demographics

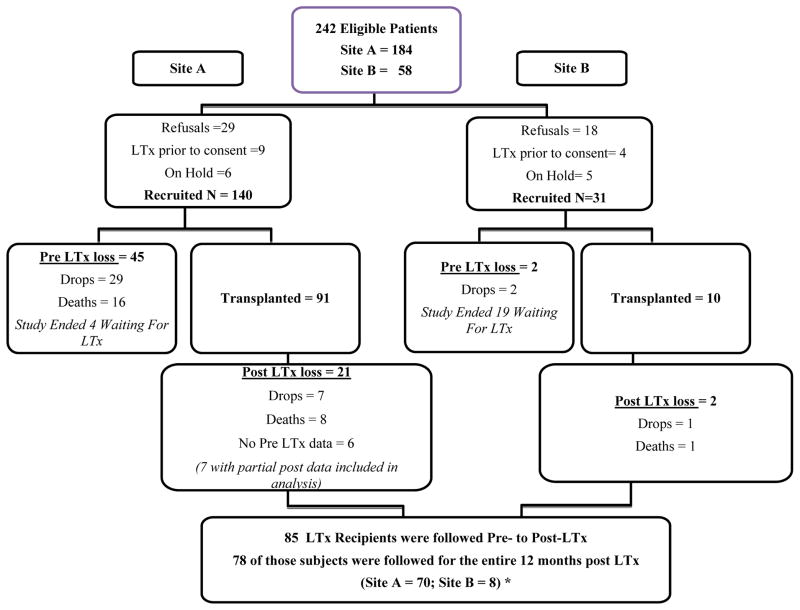

Of the 242 eligible LTx patients, 171 agreed to be in this study (140 from Site A and 31 from Site B (See Figure 1). During the pre-transplant period 50 subjects were lost to the study; 31 dropouts due to deteriorating medical conditions or due to feeling too “stressed” or busy to continue participation, and 16 deaths. One hundred and one of the remaining 124 subjects received a LTx during the study period. This report focuses on the pre- to post-LTx symptom changes of 85 (of the 101) LTx recipients for whom we had pre- and at least partial post-transplant data. Seventy-eight recipients were followed for the entire 12-month post-LTx period and 7 subjects had completed the TSI before and at least once after transplant (see Figure 1). Due to missing data and study mortality at each time point, the number of subjects who completed post-transplant TSI questionnaires that could be compared to their pre-LTx questionnaires varied (ranging from 74–80).

Figure 1.

Recruitment & Retention Flow Chart

Table 1 shows that the mean age of the LTx recipients was 46.2 yrs. of age (± SD = 12.6 yrs.) and the majority were female, (58%), white (80%), married (63%), and had a high school or greater education (75%). The most prevalent pre-transplant diagnosis was idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (28%) and the most common transplant procedure was bilateral, sequential lung transplantation (59%). Comparisons of demographic characteristics demonstrated no significant differences between the 85 LTx recipients included in this sample and the other 86 subjects (of the total subjects recruited) that were excluded (see Figure 1): sex (Fisher’s exact test p=0.877); race (χ2=2.402, p=0.493); education (χ2=3.305, p=0.192); respiratory diagnosis (χ2=6.465, p=0.264). The immunosuppressive regimen during the study period included tacrolimus, azathioprine and prednisone (31). All patients received daclizumab induction therapy at the time of transplantation. The dosing and levels of immunosuppressive medications were standardized for all patients included in this study. Tacrolimus was dosed at 0.04 mg/kg twice daily with target trough levels between 5–15 ng/ml, azathioprine was administered at 2 mg/kg daily with dose adjustments for leukopenia, and prednisone was tapered to ≤ 10 mg per day by three months post-transplantation. If there was intolerance to a particular immunosuppressive medication, changes in medications were made on an individual basis not to the program protocol.

Pre-Transplant Symptoms

Prior to LTx, SOB with activity, tiring easily, and fatigue were the highest ranked frequently occurring and distressing physical symptoms (see Table 2). Other top 10 pre-transplant symptoms rated as frequently occurring and distressing were coughing, SOB at rest, difficulty clearing secretions chest tightness, sleepiness, and decreased sexual performance. Not feeling rested after sleep was rated as among the top 10 frequently occurring symptoms, but not rated as among the most distressing symptoms. In contrast, muscle weakness of arms and legs was rated among the most distressing symptoms, but not among the top frequently occurring pre-transplant symptoms (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Pre-Lung Transplant Top Rated Frequently Occurring and Distressful Physical Symptoms (N =85)

| Symptom: | Symptom Frequency | Symptom Distress | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean 5-Point Scale (0=never to 4=always) |

95% Confidence Interval | Rating Rank | Mean 5-Point Scale (0=not at all to 4=extremely) |

95% Confidence Interval | Rating Rank | |||

| SOB w Activity | 3.38 *(0.85) | 3.20 | 3.56 | 1 | 2.53 *(1.30) | 2.25 | 2.81 | 1 |

| Tiring easily | 2.49 (1.12) | 2.25 | 2.73 | 2 | 2.01 (1.34) | 1.73 | 2.29 | 2 |

| Fatigue | 2.38 (0.83) | 2.20 | 2.56 | 3 | 1.91 (1.25) | 1.64 | 2.18 | 3 |

| Coughing | 2.21 (1.21) | 1.95 | 2.47 | 4 | 1.42 (1.28) | 1.15 | 1.69 | 6 |

| SOB @ rest | 1.65 (1.02) | 1.43 | 1.87 | 5 | 1.89 (1.33) | 1.61 | 2.17 | 4 |

| Difficulty Clearing Secretions | 1.65 (1.07) | 1.42 | 1.88 | 5 | 1.35 (1.29) | 1.08 | 1.62 | 10 |

| Chest Tightness | 1.64 (1.11) | 1.40 | 1.88 | 7 | 1.39 (1.22) | 1.13 | 1.65 | 7 |

| Sleepiness | 1.61 (1.16) | 1.36 | 1.86 | 8 | 1.36 (1.35) | 1.07 | 1.65 | 9 |

| Decreased Sexual Performance | 1.53 (1.51) | 1.21 | 1.85 | 9 | 1.38 (1.48) | 1.07 | 1.69 | 8 |

| Not feeling Rested after Sleep | 1.39 (1.01) | 1.18 | 1.60 | 10 | 1.18 (1.24) | 0.92 | 1.44 | |

| Muscle Weakness Arms & Legs | 1.32 (1.16) | 1.07 | 1.57 | 1.45 (1.45) | 1.14 | 1.76 | 5 | |

( ) = ± SD

The mean values for pre-LTx psychological symptom frequency and distress were much lower and more variable than the mean values for physical symptoms (See Table 3). The top 10 pre-transplant psychological symptoms ranked highest for being frequently occurring and/or distressing were: decreased interest in sex, feeling a lack of control, feeling restless, feeling depressed, having problems remembering, feeling helpless, having trouble concentrating, feeling nervous/apprehensive, and feeling increased irritability. An increased interest in sex was rated among the 10 most frequently occurring psychological symptoms, but was not ranked among the most distressing symptoms. In contrast, feeling sad and having mood swings were ranked among the 10 most psychologically distressing symptoms, but not rated among the top 10 frequently occurring symptoms (See Table 3).

Table 3.

Pre-Lung Transplant Top Rated Frequently Occurring and Distressful Psychological Symptoms (N =85)

| Symptom | Frequency Mean 5-Point Scale (0=never to 4=always) |

95% Confidence Interval | Rating Rank | Distress Mean 5-Point Scale (0=not at all to 4 = extremely) |

95% Confidence Interval | Rating Rank | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decreased Interest in Sex | 1.48 *(1.50 ) | 1.16 | 1.79 | 1 | 1.15 *(1.14) | 0.91 | 1.39 | 6 |

| Feelings of Lack of Control | 1.29 (1.28 ) | 1.01 | 1.56 | 2 | 1.47 (1.56) | 1.14 | 1.80 | 1 |

| Feeling Restless | 1.19 (1.03) | 0.97 | 1.40 | 3 | 0.87 (1.09) | 0.64 | 1.10 | 9 |

| Feeling Depressed | 1.07 (0.97) | 0.86 | 1.27 | 4 | 1.18 (1.23) | 0.92 | 1.44 | 5 |

| Problems Remembering | 1.06 (1.05) | 0.83 | 1.28 | 5 | 1.34 (1.46) | 1.03 | 1.65 | 2 |

| Feeling Helpless | 1.05 (1.14) | 0.80 | 1.29 | 6 | 1.26 (1.43) | 0.96 | 1.56 | 3 |

| Trouble Concentrating | 0.93 (1.07) | 0.70 | 1.15 | 7 | 1.25 (1.46) | 0.94 | 1.56 | 4 |

| Nervous/Apprehensive | 0.86 (1.01) | 0.64 | 1.07 | 8 | 0.92 (1.24) | 0.66 | 1.18 | 8 |

| Increased Irritability | 0.81 (0.85) | 0.62 | 0.99 | 9 | 0.8 0 (1.07) | 0.57 | 1.03 | 10 |

| Increased Interest in Sex | 0.75 (1.03) | 0.53 | 0.96 | 10 | 0.38 (0.99) | 0.17 | 0.59 | |

| Feeling Sad | 0.92 (0.90) | 0.72 | 1.11 | 0.94 (1.11) | 0.70 | 1.18 | 7 | |

| Mood Swings | 0.71 (0.80) | 0.53 | 0.88 | 0.8 0 1.15) | 0.56 | 1.04 | 10 | |

( ) = ± Standard Deviation

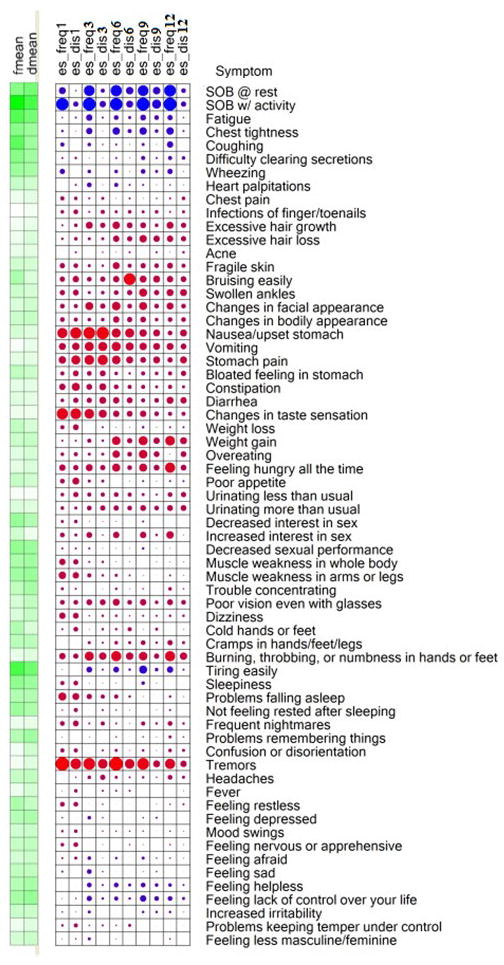

Post-Transplant Symptoms

The use of a bubble graph (Figure 2) illustrates symbolically the frequency and distress mean values of each of the 64 symptoms prior to transplant. Heat intensity mapping was used to represent the pre-LTx symptom mean values using the colors varying from light to dark green. The lighter the green color the lower the pre-LTx mean and the darker the green color the higher the pre-transplant mean. During the first year post-LTx, changes (i.e., calculated ridit effect size difference scores) from the pre-transplant symptom mean values are represented by the size and color of the solid circles (the larger the circle the larger the effect size (ES) change and vice versa. The color blue represents symptom improvement, while the color red represents symptom worsening. The absence of a solid circle represents no ES change. An examination of the patterns of symptom changes show that symptoms rated as most frequent and distressing before LTx markedly improved after transplant and new post-LTx symptoms emerged.

Figure 2. Bubble graph.

Heat intensity mapping was used to represent the pre-transplant symptom rating mean values using the colors varying from light to dark green (i.e., the darker the color green the larger the pre-transplant mean and the lighter the green color reflects the smallness of the pre-transplant symptom rating mean). The effect size change from those pre-transplant mean values during the first year post-LTx are represented by the size and color of the solid circles (the larger the circle the larger the effect size change and vice versa and the color blue represents symptom improvement and the color red represents symptom worsening. The absence of a solid circle indicates the absence of an effect size change

Fmean = pre-transplant symptom frequency mean

Dmean= pre-transplant symptom distress mean

es-Freq = ridit effect size difference of frequency of symptom occurrence

es-Dis = ridit effect size difference of symptom distress

1, 3, 6, 9. And 12 indicates the time period (1, 3, 6, 9, & 12 months) post-transplant

The time varying cohort was: at 1 month (N=80), 3 months (N=79). 6 months (N=77), 9 months (N=74), and 12 months (N=76)

While the bubble graph provides an overall depiction of the pattern of change for each of the 64 symptoms, Table 4 identifies only those symptoms with significant (p<0.05) pre- to post-transplant ES difference scores for frequency and/or distress. Tables 5 and 6 show post-LTx (i.e., 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months) raw ridit ES difference scores for symptom frequency and distress, respectively. These tables include 95% confidence intervals and False Discovery Rates (FDR).

Table 4.

Significant Post-Transplant Ridit Effect Size Changes in Symptom Frequency and/or Symptom Distress

| Symptoms post-transplant | 1 month (N=80) | 3 months (N=79) | 6 months (N=77) | 9 months (N=74) | 12 months (N=76) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOB @ rest | ↓ F* | ↓ F& D† | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D |

| SOB with Activity | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D |

| Fatigue | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D | ↓ F | |

| Chest Tightness | ↓ F | ↓ F | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D |

| Coughing | ↓ F | ↓ F | ↓ F | ↓ F | ↓ F |

| Difficulty Clearing Secretions | ↓ F | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D | ||

| Wheezing | ↓ F | ↓ F | ↓ F | ↓ F& D | ↓ F |

| Heart Palpitations | ↓ F | ↓ F& D | ↓ F | ||

| Excessive hair growth | ↑ F | ||||

| Bruising Easily | ↑ D‡ | ||||

| Swollen ankles | ↑ F | ||||

| Changes in Facial Appearance | ↑ F | ↑ F | ↑ F | ||

| Nausea/Upset Stomach | ↑ F & D | ↑ F & D | ↑ F & D | ↑ F | |

| Vomiting | ↑ F & D | ↑ F & D | |||

| Stomach Pain | ↑ D | ↑ F & D | ↑ F | ||

| Constipation | ↑ D | ||||

| Changes in Taste Sensation | ↑ F & D | ↑ F & D | |||

| Weight Loss | ↓ F | ↓ F& D | |||

| Weight Gain | ↑ F | ↑ F | ↑ F | ||

| Overeating | ↑ F | ↓ F | |||

| Feeling Hungry All of the Time | ↑ F | ↑ F | ↑ F | ||

| Poor Appetite | ↓ F | ↓ F& D | |||

| Decreased Interest in Sex | ↓ F | ||||

| Decreased Sexual Performance | ↓ F | ↓ F | |||

| Burning/Throbbing, or Numbness | ↑ F & D | ↑ F & D | ↑ F | ↑ F | |

| Hands or Feet | |||||

| Tiring Easily | ↓ F & D | ↓ F & D | ↓ F & D | ↓ F& D | |

| Sleepiness | ↓ F | ||||

| Problems Falling Asleep | ↑ F | ||||

| Not Feeling Rested After Sleep | ↓ F | ||||

| Tremors | ↑ F & D | ↑ F & D | ↑ F & D | ↑ F | ↑ F |

| Feeling Depressed | ↓ F | ↓ D | |||

| Feeling Afraid | ↓ F | ↓ F | ↓ F& D | ||

| Feeling Sad | ↓ F& D | ↓ D | |||

| Feeling Helpless | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D | |

| Feeling Lack of Control Over Life | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D | ↓ F& D | |

| Increased Irritability | ↓ F | ↓ F& D | ↓ F | ||

| Feeling Less Masculine/Feminine | ↓ F |

Arrows indicate if there are increases or decreases in ridit effect size difference scores

↑ = Significant (p<0.05) increase

↓ = Significant (p<0.05) decrease

(F) = Symptom Frequency

(D) = Symptom Distress

(F&D) = Symptom Frequency and Distress.

Table 5.

Pre-transplant Symptom Frequency Means and Standard Deviations and Post-transplant Ridit Effect Size Difference Scores (with FDRb adjusted posterior probabilities)

| Symptom Measure | Pre Mean | Pre SD | 1 Month | FDRb | 3 Month | FDR | 6 Month | FDR | 9 Month | FDR | 12 Month | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOB @ rest | 1.65 | 1.02 | −0.60 | <.0001 | −0.82 | <.0001 | −0.87 | <.0001 | −0.85 | <.0001 | −0.89 | <.0001 |

| SOB w/activity | 3.38 | 0.85 | −0.93 | <.0001 | −0.98 | <.0001 | −0.95 | <.0001 | −0.97 | <.0001 | −0.96 | <.0001 |

| Fatigue | 2.38 | 0.83 | −0.26 | 0.0856 | −0.57 | <.0001 | −0.46 | 0.0006 | −0.53 | <.0001 | −0.52 | 0.0001 |

| Chest tightness | 1.64 | 1.11 | −0.32 | 0.0376 | −0.58 | <.0001 | −0.62 | <.0001 | −0.62 | <.0001 | −0.65 | <.0001 |

| Coughing | 2.21 | 1.21 | −0.43 | 0.0013 | −0.39 | 0.0027 | −0.31 | 0.024 | −0.36 | 0.0099 | −0.56 | <.0001 |

| Difficulty clearing secretions | 1.65 | 1.07 | −0.02 | 0.848 | −0.23 | 0.0939 | −0.31 | 0.0245 | −0.44 | 0.0014 | −0.44 | 0.0011 |

| Wheezing | 1.4 | 1.06 | −0.49 | 0.0002 | −0.40 | 0.0022 | −0.41 | 0.0021 | −0.46 | 0.0007 | −0.49 | 0.0002 |

| Heart palpitations | 0.85 | 0.99 | −0.19 | 0.2205 | −0.47 | 0.0003 | −0.43 | 0.0014 | −0.3 | 0.036 | −0.28 | 0.0575 |

| Chest pain | 0.36 | 0.71 | 0.086 | 0.6334 | −0.03 | 0.8688 | −0.09 | 0.535 | −0.1 | 0.5088 | −0.03 | 0.8126 |

| Infections of finger/toenails | 0.12 | 0.55 | 0.063 | 0.7437 | −0.03 | 0.8599 | 0.031 | 0.8393 | 0.039 | 0.7911 | −0.04 | 0.7978 |

| Excessive hair growth | 0.31 | 0.76 | −0.03 | 0.8343 | 0.268 | 0.0591 | 0.297 | 0.0337 | 0.199 | 0.1708 | 0.264 | 0.0744 |

| Excessive hair loss | 0.35 | 0.79 | −0.02 | 0.8753 | 0.025 | 0.9096 | 0.232 | 0.1144 | 0.282 | 0.0508 | 0.225 | 0.1325 |

| Acne | 0.43 | 0.68 | −0.16 | 0.3304 | −0.14 | 0.3346 | −0.09 | 0.5299 | −0.13 | 0.372 | −0.1 | 0.4805 |

| Fragile skin | 0.73 | 1.19 | 0.148 | 0.3913 | 0.007 | 0.9696 | 0.243 | 0.1023 | 0.162 | 0.2642 | 0.183 | 0.224 |

| Bruising easily | 1.2 | 1.34 | 0.148 | 0.3913 | 0.121 | 0.4646 | 0.226 | 0.1186 | 0.256 | 0.0786 | 0.238 | 0.1047 |

| Swollen ankles | 0.78 | 1.05 | 0.151 | 0.3913 | 0.034 | 0.8688 | 0.13 | 0.4123 | 0.309 | 0.0321 | 0.253 | 0.0847 |

| Changes in facial appearance | 0.62 | 1.07 | 0.127 | 0.4852 | 0.315 | 0.0214 | 0.34 | 0.0151 | 0.318 | 0.0286 | 0.252 | 0.0847 |

| Changes in bodily appearance | 0.8 | 1.13 | 0.125 | 0.4852 | 0.059 | 0.7615 | 0.231 | 0.1143 | 0.192 | 0.188 | 0.135 | 0.3842 |

| Nausea/upset stomach | 0.65 | 0.83 | 0.459 | 0.0005 | 0.568 | <.0001 | 0.401 | 0.0031 | 0.283 | 0.0482 | 0.121 | 0.4244 |

| Vomiting | 0.2 | 0.55 | 0.267 | 0.0856 | 0.398 | 0.0023 | 0.392 | 0.0039 | 0.278 | 0.0508 | 0.258 | 0.0804 |

| Stomach pain | 0.46 | 0.73 | 0.301 | 0.0557 | 0.406 | 0.0021 | 0.349 | 0.0122 | 0.201 | 0.1648 | 0.145 | 0.3472 |

| Bloated feeling in stomach | 0.91 | 1.13 | 0.098 | 0.589 | 0.116 | 0.4897 | 0.067 | 0.6604 | 0.08 | 0.5884 | 0.096 | 0.5002 |

| Constipation | 0.47 | 0.73 | 0.223 | 0.1594 | 0.177 | 0.238 | 0.115 | 0.4821 | 0.086 | 0.5553 | 0.097 | 0.5002 |

| Diarrhea | 0.55 | 0.73 | 0.048 | 0.7725 | 0.158 | 0.2984 | 0.213 | 0.1425 | 0.079 | 0.5884 | 0.261 | 0.0786 |

| Changes in taste sensation | 0.33 | 0.71 | 0.506 | 0.0001 | 0.409 | 0.0021 | 0.235 | 0.107 | 0.214 | 0.1446 | 0.086 | 0.5575 |

| Weight loss | 0.94 | 1.14 | 0.08 | 0.6594 | −0.16 | 0.291 | −0.22 | 0.1215 | −0.33 | 0.0177 | −0.29 | 0.0493 |

| Weight gain | 0.82 | 1.04 | −0.03 | 0.8424 | 0.091 | 0.5952 | 0.353 | 0.011 | 0.38 | 0.0067 | 0.427 | 0.0017 |

| Overeating | 0.55 | 0.83 | 0.049 | 0.7725 | 0.014 | 0.9443 | 0.275 | 0.0598 | 0.365 | 0.0099 | −0.25 | 0.0293 |

| Feeling hungry all the time | 0.45 | 0.85 | 0.23 | 0.1559 | 0.244 | 0.0832 | 0.319 | 0.0231 | 0.333 | 0.0189 | 0.439 | 0.0012 |

| Poor appetite | 0.85 | 1.16 | 0.125 | 0.4852 | 0.017 | 0.9376 | −0.12 | 0.4372 | −0.29 | 0.0442 | −0.29 | 0.0493 |

| Urinating less than usual | 0.21 | 0.62 | 0.073 | 0.6834 | 0.094 | 0.5765 | 0.109 | 0.508 | 0.025 | 0.867 | 0.127 | 0.4089 |

| Urinating more than usual | 0.6 | 1.04 | 0.042 | 0.7944 | 0.107 | 0.5346 | 0.161 | 0.3014 | 0.182 | 0.2116 | 0.201 | 0.179 |

| Decreased interest in sex | 1.48 | 1.5 | 0.037 | 0.8343 | −0.25 | 0.0818 | −0.24 | 0.1051 | −0.29 | 0.0465 | −0.2 | 0.196 |

| Increased interest in sex | 0.75 | 1.03 | 0.111 | 0.5549 | 0.19 | 0.2147 | 0.237 | 0.1186 | 0.217 | 0.1578 | 0.284 | 0.0715 |

| Decreased sexual performance | 1.53 | 1.51 | −0.03 | 0.848 | −0.31 | 0.0317 | −0.24 | 0.1144 | −0.32 | 0.036 | −0.24 | 0.1102 |

| Muscle weakness in whole body | 1.21 | 1.17 | 0.234 | 0.149 | −0.04 | 0.8092 | −0.1 | 0.518 | −0.17 | 0.2213 | −0.09 | 0.4936 |

| Muscle weakness in arms or legs | 1.32 | 1.16 | 0.273 | 0.0841 | 0.08 | 0.6424 | 0.011 | 0.9585 | −0.11 | 0.4479 | −0.04 | 0.7978 |

| Trouble concentrating | 0.93 | 1.07 | 0.033 | 0.8343 | −0.13 | 0.3898 | 0.005 | 0.984 | −0.08 | 0.5453 | 0.058 | 0.7025 |

| Poor vision even with glasses | 0.65 | 0.96 | 0.12 | 0.4973 | 0.191 | 0.1969 | 0.257 | 0.083 | 0.223 | 0.1238 | 0.203 | 0.1751 |

| Dizziness | 0.62 | 0.89 | 0.214 | 0.175 | −0.08 | 0.6187 | 0.001 | 0.9869 | −0.04 | 0.7617 | −0.01 | 0.9199 |

| Cold hands or feet | 1.11 | 1.18 | −0.05 | 0.7725 | −0.1 | 0.5502 | −0 | 0.9864 | −0.09 | 0.5088 | −0.19 | 0.196 |

| Cramps in hands/feet/legs | 0.99 | 1.2 | −0.19 | 0.2262 | 0.018 | 0.9376 | 0.053 | 0.7329 | 0.138 | 0.3549 | 0.168 | 0.2708 |

| Burning, throbbing, or numbness in hands or feet | 0.4 | 0.92 | 0.224 | 0.1594 | 0.399 | 0.0023 | 0.443 | 0.0012 | 0.346 | 0.015 | 0.457 | 0.0008 |

| Tiring easily | 2.49 | 1.12 | −0.22 | 0.1564 | −0.53 | <.0001 | −0.54 | <.0001 | −0.67 | <.0001 | −0.57 | <.0001 |

| Sleepiness | 1.61 | 1.16 | 0.096 | 0.5895 | −0.25 | 0.0767 | −0.23 | 0.1051 | −0.39 | 0.0049 | −0.21 | 0.1619 |

| Problems falling asleep | 1.12 | 1.17 | 0.32 | 0.0376 | 0.15 | 0.3217 | 0.078 | 0.6081 | −0.1 | 0.4906 | 0.001 | 0.9915 |

| Not feeling rested after sleeping | 1.39 | 1.01 | −0.07 | 0.6882 | −0.20 | 0.1662 | −0.26 | 0.0718 | −0.16 | 0.2647 | −0.29 | 0.0494 |

| Frequent nightmares | 0.32 | 0.64 | 0.136 | 0.4521 | −0.05 | 0.7799 | −0.03 | 0.8261 | 0.103 | 0.4906 | 0.113 | 0.4448 |

| Problems remembering things | 1.06 | 1.05 | −0.24 | 0.1365 | −0.24 | 0.0818 | −0.06 | 0.6604 | −0.06 | 0.6554 | 0.029 | 0.8459 |

| Confusion or disorientation | 0.29 | 0.67 | 0.09 | 0.6222 | −0.16 | 0.291 | 0.013 | 0.9471 | −0 | 0.9449 | 0.042 | 0.7978 |

| Tremors | 0.28 | 0.7 | 0.644 | <.0001 | 0.549 | <.0001 | 0.671 | <.0001 | 0.548 | <.0001 | 0.448 | 0.001 |

| Headaches | 0.89 | 0.96 | −0.14 | 0.4285 | 0.058 | 0.7615 | 0.026 | 0.8729 | −0.01 | 0.9449 | 0.114 | 0.4448 |

| Fever | 0.38 | 0.69 | −0.09 | 0.5895 | −0.18 | 0.2216 | −0.05 | 0.7329 | −0.14 | 0.3178 | −0.13 | 0.3978 |

| Feeling restless | 1.19 | 1.03 | 0.12 | 0.4973 | −0.12 | 0.4307 | −0.15 | 0.3031 | −0.14 | 0.3178 | −0.08 | 0.5875 |

| Feeling depressed | 1.07 | 0.97 | −0.27 | 0.0841 | −0.39 | 0.0027 | −0.18 | 0.223 | −0.27 | 0.0508 | −0.2 | 0.1626 |

| Mood swings | 0.71 | 0.8 | −0.02 | 0.8753 | −0.20 | 0.1662 | −0.07 | 0.6343 | −0.09 | 0.5307 | −0.07 | 0.6348 |

| Feeling nervous or apprehensive | 0.86 | 1.01 | 0.046 | 0.7748 | −0.20 | 0.1502 | −0.12 | 0.4123 | −0.25 | 0.0786 | −0.06 | 0.6353 |

| Feeling afraid | 0.69 | 0.91 | −0.05 | 0.7725 | −0.40 | 0.0022 | −0.33 | 0.0151 | −0.39 | 0.0053 | −0.28 | 0.0575 |

| Feeling sad | 0.92 | 0.9 | −0.29 | 0.0566 | −0.46 | 0.0003 | −0.21 | 0.1466 | −0.25 | 0.0786 | −0.14 | 0.3354 |

| Feeling helpless | 1.05 | 1.14 | −0.21 | 0.1662 | −0.48 | 0.0002 | −0.47 | 0.0005 | −0.45 | 0.0008 | −0.39 | 0.004 |

| Feeling lack of control over your life | 1.29 | 1.28 | −0.24 | 0.1404 | −0.5 | <.0001 | −0.43 | 0.0013 | −0.56 | <.0001 | −0.45 | 0.0008 |

| Increased irritability | 0.81 | 0.85 | −0.26 | 0.0856 | −0.38 | 0.0028 | −0.22 | 0.1293 | −0.34 | 0.015 | −0.33 | 0.0251 |

| Problems keeping temper under control | 0.34 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 0.9947 | −0.26 | 0.0656 | −0.06 | 0.6585 | −0.18 | 0.2112 | −0.13 | 0.3842 |

| Feeling less masculine/feminine | 0.67 | 0.97 | −0.22 | 0.1564 | −0.36 | 0.005 | −0.25 | 0.0959 | −0.21 | 0.1501 | −0.27 | 0.0688 |

= negative (−) effect size changes indicate improvement from pre transplant symptom mean, while positive effect sizes indicate increases in new symptoms

FDR = False Discovery Rate

Table 6.

Pre-transplant Symptom Distress Means and Standard Deviations and Post-transplant Ridit Effect Size Difference Scores (with FDRb adjusted posterior probabilities)

| Symptom Measure | Pre Mean | Pre SD | 1 Month | FDRb | 3 Month | FDR | 6 Month | FDR | 9 Month | FDR | 12 Month | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOB @ rest | 1.89 | 1.33 | −0.28 | 0.0683 | −0.44 | 0.0007 | −0.63 | <.0001 | −0.64 | <.0001 | −0.48 | 0.0003 |

| SOB w/activity | 2.53 | 1.3 | −0.50 | 0.0001 | −0.57 | <.0001 | −0.59 | <.0001 | −0.74 | <.0001 | −0.52 | 0.0001 |

| Fatigue | 1.91 | 1.25 | −0.29 | 0.0591 | −0.31 | 0.0217 | −0.36 | 0.0085 | −0.46 | 0.0007 | −0.27 | 0.0627 |

| Chest tightness | 1.39 | 1.22 | −0.09 | 0.589 | −0.23 | 0.0939 | −0.45 | 0.0007 | −0.41 | 0.0029 | −0.3 | 0.0481 |

| Coughing | 1.42 | 1.28 | −0.15 | 0.3845 | −0.08 | 0.6171 | −0.09 | 0.5299 | −0.25 | 0.0799 | −0.21 | 0.1565 |

| Difficulty clearing secretions | 1.35 | 1.29 | 0.001 | 0.9947 | −0.10 | 0.5475 | −0.23 | 0.1051 | −0.3 | 0.036 | −0.42 | 0.0018 |

| Wheezing | 1.26 | 1.28 | −0.21 | 0.1662 | −0.17 | 0.2382 | −0.24 | 0.1023 | −0.37 | 0.0088 | −0.24 | 0.0886 |

| Heart palpitations | 0.73 | 1.08 | −0.05 | 0.7725 | −0.24 | 0.0818 | −0.31 | 0.024 | −0.24 | 0.0872 | −0.1 | 0.4854 |

| Chest pain | 0.48 | 0.97 | 0.061 | 0.7523 | 0.015 | 0.9437 | −0.03 | 0.8261 | −0.06 | 0.6554 | 0.05 | 0.7556 |

| Infections of finger/toenails | 0.31 | 0.89 | 0.119 | 0.4973 | 0.074 | 0.6901 | 0.054 | 0.7329 | 0.043 | 0.7733 | 0.029 | 0.8459 |

| Excessive hair growth | 0.41 | 1.05 | 0.052 | 0.7725 | 0.147 | 0.3319 | 0.176 | 0.2498 | 0.05 | 0.7361 | 0.156 | 0.3192 |

| Excessive hair loss | 0.6 | 1.27 | 0.067 | 0.722 | 0.039 | 0.8599 | 0.158 | 0.303 | 0.208 | 0.1616 | 0.155 | 0.3257 |

| Acne | 0.46 | 0.95 | −0.03 | 0.8343 | −0.07 | 0.7098 | −0.03 | 0.8261 | −0.05 | 0.7156 | −0.01 | 0.898 |

| Fragile skin | 0.67 | 1.16 | 0.114 | 0.52 | −0.00 | 0.9691 | 0.082 | 0.5922 | 0.134 | 0.37 | 0.073 | 0.6229 |

| Bruising easily | 0.64 | 1.05 | 0.226 | 0.1564 | 0.156 | 0.2984 | 0.563 | <.0001 | 0.243 | 0.0873 | 0.203 | 0.1751 |

| Swollen ankles | 0.65 | 1.03 | 0.196 | 0.2235 | 0.069 | 0.7108 | 0.159 | 0.3014 | 0.167 | 0.2521 | 0.255 | 0.0837 |

| Changes in facial appearance | 0.76 | 1.21 | 0.098 | 0.589 | 0.155 | 0.3028 | 0.107 | 0.508 | 0.127 | 0.3892 | 0.122 | 0.4244 |

| Changes in bodily appearance | 0.85 | 1.21 | 0.087 | 0.6246 | 0.047 | 0.8123 | 0.163 | 0.2969 | 0.071 | 0.6361 | 0.11 | 0.4504 |

| Nausea/upset stomach | 0.53 | 0.88 | 0.506 | 0.0001 | 0.588 | <.0001 | 0.404 | 0.0029 | 0.239 | 0.0925 | 0.25 | 0.0855 |

| Vomiting | 0.39 | 0.89 | 0.274 | 0.0841 | 0.374 | 0.0043 | 0.314 | 0.024 | 0.254 | 0.0786 | 0.185 | 0.217 |

| Stomach pain | 0.46 | 0.85 | 0.40 | 0.0036 | 0.47 | 0.0003 | 0.245 | 0.1023 | 0.251 | 0.0799 | 0.265 | 0.0744 |

| Bloated feeling in stomach | 0.78 | 1.11 | 0.195 | 0.2235 | 0.202 | 0.1662 | −0 | 0.984 | 0.064 | 0.665 | 0.15 | 0.3346 |

| Constipation | 0.49 | 0.91 | 0.314 | 0.0415 | 0.246 | 0.0818 | 0.106 | 0.508 | 0.012 | 0.9425 | 0.032 | 0.8347 |

| Diarrhea | 0.46 | 0.81 | 0.149 | 0.3913 | 0.264 | 0.0635 | 0.178 | 0.2448 | 0.118 | 0.4265 | 0.224 | 0.1281 |

| Changes in taste sensation | 0.34 | 0.84 | 0.499 | 0.0001 | 0.317 | 0.0211 | 0.175 | 0.2498 | 0.132 | 0.372 | 0.076 | 0.6127 |

| Weight loss | 0.67 | 1.06 | 0.205 | 0.2049 | −0.05 | 0.7799 | −0.09 | 0.535 | −0.25 | 0.0786 | −0.29 | 0.0493 |

| Weight gain | 0.88 | 1.31 | −0.05 | 0.7725 | −0.01 | 0.9376 | 0.164 | 0.2969 | 0.222 | 0.1238 | 0.258 | 0.0804 |

| Overeating | 0.68 | 1.2 | 0.075 | 0.6791 | 0.012 | 0.9459 | 0.131 | 0.4123 | 0.188 | 0.2033 | 0.182 | 0.2266 |

| Feeling hungry all the time | 0.6 | 1.15 | 0.165 | 0.3304 | 0.157 | 0.2984 | 0.113 | 0.4947 | 0.18 | 0.2116 | 0.194 | 0.1945 |

| Poor appetite | 0.71 | 1.06 | 0.245 | 0.1324 | 0.032 | 0.876 | −0.1 | 0.5121 | −0.24 | 0.0853 | −0.29 | 0.0493 |

| Urinating less than usual | 0.24 | 0.73 | 0.146 | 0.3982 | 0.1 | 0.5502 | 0.095 | 0.535 | −0.03 | 0.8303 | 0.169 | 0.2708 |

| Urinating more than usual | 0.53 | 1.08 | 0.022 | 0.8753 | 0.17 | 0.258 | 0.108 | 0.508 | 0.118 | 0.4295 | 0.177 | 0.2416 |

| Decreased interest in sex | 1.15 | 1.14 | 0.052 | 0.7725 | −0.11 | 0.5258 | −0.2 | 0.182 | −0.17 | 0.2521 | −0.13 | 0.4089 |

| Increased interest in sex | 0.38 | 0.99 | 0.008 | 0.9603 | −0.06 | 0.7615 | −0.14 | 0.3767 | −0.01 | 0.9425 | −0.11 | 0.4448 |

| Decreased sexual performance | 1.38 | 1.48 | −0.02 | 0.8524 | −0.22 | 0.1379 | −0.25 | 0.1023 | −0.22 | 0.1523 | −0.12 | 0.4244 |

| Muscle weakness in whole body | 1.35 | 1.46 | 0.166 | 0.3304 | −0.02 | 0.9096 | −0.09 | 0.5292 | −0.22 | 0.1224 | −0.11 | 0.4448 |

| Muscle weakness in arms or legs | 1.45 | 1.45 | 0.234 | 0.149 | −0 | 0.9764 | −0.03 | 0.8261 | −0.19 | 0.1779 | −0.1 | 0.4504 |

| Trouble concentrating | 1.25 | 1.46 | −0.04 | 0.7748 | −0.1 | 0.5435 | −0.11 | 0.4818 | −0.18 | 0.2105 | −0.07 | 0.6208 |

| Poor vision even with glasses | 0.93 | 1.36 | 0.123 | 0.4955 | 0.189 | 0.2004 | 0.132 | 0.4123 | 0.062 | 0.6714 | 0.131 | 0.3978 |

| Dizziness | 0.84 | 1.24 | 0.19 | 0.2336 | 0 | 0.9953 | −0.09 | 0.5414 | −0.05 | 0.7156 | −0 | 0.9825 |

| Cold hands or feet | 0.62 | 1 | 0.121 | 0.4973 | −0 | 0.9953 | 0.093 | 0.535 | 0.028 | 0.8535 | −0.11 | 0.4448 |

| Cramps in hands/feet/legs | 1.02 | 1.31 | −0.15 | 0.3821 | −0.03 | 0.8688 | 0.023 | 0.8877 | −0 | 0.9641 | 0.023 | 0.882 |

| Burning, throbbing, or numbness in hands or feet | 0.56 | 1.15 | 0.165 | 0.3304 | 0.279 | 0.0458 | 0.302 | 0.0323 | 0.148 | 0.3178 | 0.283 | 0.0575 |

| Tiring easily | 2.01 | 1.34 | −0.18 | 0.2493 | −0.31 | 0.0219 | −0.33 | 0.0167 | −0.41 | 0.0029 | −0.32 | 0.0301 |

| Sleepiness | 1.36 | 1.35 | 0.111 | 0.5389 | −0.11 | 0.489 | −0.15 | 0.303 | −0.11 | 0.4446 | −0.19 | 0.1945 |

| Problems falling asleep | 1.15 | 1.35 | 0.256 | 0.1066 | 0.096 | 0.5687 | −0 | 0.9787 | −0.18 | 0.2089 | −0.11 | 0.4396 |

| Not feeling rested after sleeping | 1.18 | 1.24 | 0.10 | 0.589 | −0.02 | 0.9003 | −0.1 | 0.508 | −0.09 | 0.5109 | −0.15 | 0.306 |

| Frequent nightmares | 0.42 | 1.04 | 0.195 | 0.2235 | 0.101 | 0.5502 | −0.1 | 0.518 | −0.01 | 0.941 | 0.001 | 0.9915 |

| Problems remembering things | 1.34 | 1.46 | −0.17 | 0.291 | −0.22 | 0.1222 | −0.13 | 0.3815 | −0.09 | 0.5176 | −0.07 | 0.6348 |

| Confusion or disorientation | 0.71 | 1.37 | 0.077 | 0.6744 | −0.03 | 0.876 | −0.1 | 0.518 | −0.1 | 0.5029 | 0.021 | 0.8868 |

| Tremors | 0.56 | 1.16 | 0.472 | 0.0003 | 0.426 | 0.0012 | 0.405 | 0.0029 | 0.265 | 0.0698 | 0.237 | 0.1047 |

| Headaches | 0.94 | 1.15 | −0.07 | 0.6791 | 0.16 | 0.2949 | −0.03 | 0.8261 | −0.06 | 0.6554 | 0.032 | 0.8347 |

| Fever | 0.67 | 1.21 | 0.05 | 0.7725 | −0.05 | 0.7799 | −0.05 | 0.7329 | −0.13 | 0.372 | −0.11 | 0.4396 |

| Feeling restless | 0.87 | 1.09 | 0.134 | 0.4608 | −0.08 | 0.6351 | −0.15 | 0.303 | −0.12 | 0.4238 | −0.04 | 0.7978 |

| Feeling depressed | 1.18 | 1.23 | −0.20 | 0.2049 | −0.26 | 0.0656 | −0.18 | 0.2237 | −0.31 | 0.0311 | −0.16 | 0.306 |

| Mood swings | 0.8 | 1.15 | 0.05 | 0.7725 | −0.06 | 0.7615 | −0.07 | 0.6081 | −0.13 | 0.3548 | −0.1 | 0.4854 |

| Feeling nervous or apprehensive | 0.92 | 1.24 | 0.106 | 0.5549 | −0.09 | 0.563 | −0.07 | 0.6081 | −0.2 | 0.1626 | −0.12 | 0.4183 |

| Feeling afraid | 0.79 | 1.18 | 0.023 | 0.8723 | −0.23 | 0.1023 | −0.21 | 0.1414 | −0.28 | 0.047 | −0.24 | 0.099 |

| Feeling sad | 0.94 | 1.11 | −0.13 | 0.4624 | −0.27 | 0.0458 | −0.15 | 0.3014 | −0.28 | 0.045 | −0.14 | 0.3691 |

| Feeling helpless | 1.26 | 1.43 | −0.12 | 0.4852 | −0.31 | 0.0219 | −0.35 | 0.01 | −0.4 | 0.0032 | −0.3 | 0.0445 |

| Feeling lack of control over your life | 1.47 | 1.56 | −0.08 | 0.6246 | −0.34 | 0.009 | −0.33 | 0.0151 | −0.49 | 0.0003 | −0.38 | 0.0055 |

| Increased irritability | 0.8 | 1.07 | −0.10 | 0.5549 | −0.19 | 0.1969 | −0.16 | 0.3005 | −0.33 | 0.0189 | −0.23 | 0.1115 |

| Problems keeping temper under control | 0.54 | 1.08 | 0.081 | 0.6558 | −0.03 | 0.8599 | 0.035 | 0.8261 | −0.12 | 0.3847 | −0.14 | 0.3414 |

| Feeling less masculine/feminine | 0.81 | 1.21 | −0.08 | 0.6246 | −0.22 | 0.1222 | −0.2 | 0.1617 | −0.17 | 0.2213 | −0.14 | 0.3414 |

= negative (−) effect size changes indicate improvement from pre transplant symptom mean, while positive effect sizes indicate increases in new symptoms

FDR = False Discovery Rate

For the following discussion, a negative ES difference score indicates improvement of the symptom from the pre-transplant value and a positive ES difference score indicates the symptom is worsening from the pre-transplant value. Only those symptoms that significantly (p< 0.05) changed in both frequency and distress are discussed. As shown in Table 4 (ridit difference scores can be found in Tables 5 and 6), at one month post-LTx significant (p<0.05) negative ES difference scores (i.e., improvement) were found for the following symptoms: SOB with activity at 1 month (symptom frequency/distress = −0.93/−0.50), 3 month (−0.98/−0.57), 6 months (−0.95/−0.59), 9 months (−0.97/−0.74), and 12 months (0.96/−0.52). At 3 months post-LTx, feeling sad (−0.46/−0.27) decreased (p< 0.05). Significantly less fatigue was reported at 3 (−0.57/−0.31), 6 (−0.46/−0.36) and 9 (−0.53/−0.46) months. Significant (p<0.05) improvements were also seen at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months, respectively (see Tables 4, 5 & 6) for the following symptoms: SOB at rest (−0.82/−0.44; −0.87/−0.63; −0.85/−0.64; −0.89/−0.48), tiring easily (−0.53/−0.31; −0.54/−0.33;−0.67/−0.41;−0.57/−0.32), feeling helpless (−0.48/−0.31; −0.47/−0.35; −0.45/−0.40; −0.39/−0.30), and feeling a lack of control (−0.5/−0.34; −0.43/−0.33; −0.56/−0.49;−0.45/−0 38). Marked (p<0.05) improvement in heart palpitations was seen at 6 months (−0.43/−0.31) and significant (p< 0.05) reductions in chest tightness (−0.62/−0.45; −0.62/−0.41; −0.65/−0.30) were found at 6, 9, and 12 months, respectively. Nine months after LTx, improvements (p<0.05) were found for wheezing (−0.46/−0.37), feeling afraid (−0.39/−0.28) and increased irritability (−0.34/−0.33). Difficulty clearing secretions (−0.44/−0.30;−0.44/−0.42) got better (p< 0.05) at 9 and 12 months, respectively. By 12 months post-LTx, weight loss (−0.29/−0.29) and poor appetite (−0.29/−0.29) improved (p<0.05).

While remarkable post-LTx improvements were seen in symptoms that were problematic prior to transplant, new symptoms (See Figure 2 and Tables 4, 5, and 6) emerged. At 1 month post-LTx, significant (p ≤ 0.05) positive (i.e., worsening) ridit ES difference scores for frequency/distress were seen for the frequency and distress of nausea (0.46/0.51), changes in taste (0.51/0.50), and tremors (0.64/0.47). The greatest number of new significant (p ≤ 0.05) frequently occurring and distressful adverse symptoms occurred 3 months after LTx and included nausea (0.57/0.59), changes in taste (0.41/0.32), and tremors (0.55/0.43) as well as the additional symptoms of vomiting (0.40/0.37), stomach pain (0.47/0.47), and burning or numbness of hands and/or feet (0.40/0.28). Six months post-LTx, nausea (0.40/0.40), vomiting (0.39/0.31), tremors 0.67/0.41), and burning or numbness of hands and/or feet (0.44/0.30) continued to be frequently occurring and distressful. However, by 9 and 12 months post-LTx, significant (p<0.05) changes in both frequency and distress of the above symptoms were no longer found. While the preceding discussion of findings identified symptoms that significantly changed in both frequency and distress, several symptoms had significant (p<0.5) ES changes in only the frequency (e.g., the frequency of coughing diminished throughout the 12 month study period) or only in distress (e.g., the distress related to constipation was found only at 1 month post-LTx).

Additional support for the comprehensiveness of the TSI’s list of symptoms was demonstrated in this study since only 12 symptoms were reported in response to the open-ended question requesting the listing of additional symptoms not listed on the TSI. During the pre- to post-transplant study periods only 12 symptoms were added: 10 symptoms were reported once by one subject and two symptoms, (i.e., muscle tightness and urinary incontinence) were reported once by two subjects.

Discussion

Symptom assessment and management are essential to providing quality care (21) and detecting early signs of potential complications. This is the largest longitudinal study to report symptom experiences of patients before and during the first year after lung transplantation. A very unique contribution of this study is the use of ridit analysis and the bubble graph to show the effect size changes (i.e., improving, worsening, or no change) post-LTx in all of the 64 symptoms that were measured.

Before LTx, we found that patients generally rated physical symptoms (e.g., dyspnea) as more frequently occurring and distressing than psychological symptoms. These findings are consistent with the idea that the most essential basic physiological needs, such as being able to breathe, have primacy over other higher level needs (32). In accord with other studies (7, 9, 10, 17, 33, 34) an immediate and sustained improvement in respiratory symptoms (e.g., SOB at rest) was found after LTx. Likewise, the post-LTx marked improvement in fatigue, tiredness, and affective symptoms are also consistent with findings of previous research (7, 9, 17).

Our findings of post-LTx gastrointestinal (e.g., nausea) and neurological (e.g., tremors) symptoms are in line with previous studies (6, 7). However, our design also allowed us to report the symptoms within a context of time. The greatest number of gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms was found early in the post-LTx period when the immunosuppressive medication dosages are typically highest (21). By nine to twelve months post-transplant, when recipients are usually taking maintenance-level dosages of immunosuppressive medications, no significant frequent and distressing gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms were found. Although most of the symptoms that worsened after LTx could be attributed to side-effects of immunosuppressive medications, it must be kept in mind that there may be other contributing factors (e.g., anesthesia, surgery, co-morbid conditions, side-effects associated with other medications, etc.) (17, 21). Throughout the 12-month post-LTx study period, we found that the most frequently occurring symptoms were not always the most distressing or vice versa which concurs with the findings of previous studies (3, 15, 20, 21).

The experience of these frequently occurring and distressing symptoms can have a profound impact on patient outcomes. Previous investigations have suggested a relationship between adverse symptom experience and non-adherence to post-transplant medication regimens (35). Findings from this study provide evidence-based information on patterns of symptom changes that can be used by investigators and clinicians as a guide to understanding when and what kind of symptom changes LTx candidates and recipients can expect to experience. Educating patients about symptoms within a typical time context (e.g., when they may occur or go away) may have an impact on their adherence to their medication regimen. This study demonstrated that patients are willing and able to report their symptoms using the TSI. While it may seem intuitive that patients will report symptoms at clinic visits, using a symptom inventory may empower patients to address symptoms they otherwise might be hesitant to report (e.g. psychological symptoms, change in interest in sex). In addition to preparing the patient for anticipated symptoms, a symptom inventory can also be used by health professionals to teach patients and family members to monitor symptoms which may be indicative of a potential problem. For example, prior knowledge of new onset gastrointestinal symptoms including nausea, abdominal discomfort, and weight gain may encourage patients to report these symptoms earlier in their post-transplant course. This early reporting may, in turn, allow for earlier therapeutic interventions (e.g., anti-emetic medications and proton pump inhibitors, nutritional counseling regarding weight fluctuations, etc.) to alleviate these symptoms and potentially lead to better outcomes. The findings from this study can also assist health care providers to anticipate likely time points that LTx recipients’ symptoms may occur and then work with patients to develop patient-centered strategies to combat the frequency and/or distress associated with those symptoms.

It is difficult to compare studies on symptom frequency and symptom distress because symptom measurement tools and the number of symptom items in the tools vary. However, when the individual symptom items in the symptom frequency and symptom distress questionnaires are reported, as they are in this report and others (3, 7, 11, 17, 36), it is possible to examine similarities in symptom outcomes. The bubble graph (Figure 2) lists all the symptoms included in the TSI. The list of TSI symptoms and Tables 5 and 6 of the ridit ES difference scores can be used for comparisons by future investigators of LTx symptom experiences.

Koller and colleagues (25) used a creative 2-dimensional graph to illustrate the symptom frequency and distress of kidney transplant recipients at 1 year post-transplant. Our study takes innovativeness one step further. Not only do we present a traditional report of significant changes in the symptom experience over time (Tables 4-6), we also used the bubble graph to show 3-dimensional (directionality, magnitude, and time) pattern of changes in all of the symptoms measured.

In conclusion, the post-LTx findings of this study showed recipients’ reports of dramatic and sustained improvement in the pre-transplant symptoms that they rated as frequently occurring and distressing. The emergence and changing patterns of new post-LTx symptoms reported during the first year post-LTx were also presented. Using a prospective, longitudinal design allowed us to follow the same subjects before and after LTx and show that the pattern of significant effect size change (or lack of change) in the frequency and distress of the 64 symptoms is time-dependent. Clinicians can use the findings to help patients and their families anticipate what general changes in symptoms they might encounter and the important role self-monitoring and reporting of symptoms might play in the early detection of potential problems (7).

Study Limitations

Since the analysis of the data focused on patients who were able to complete the TSI before and after LTx, a potential limitation of this study is survivor bias. The generalizability of the findings is influenced by the demographic characteristics of our sample which consists of patients who were treated in the two centers and agreed to participate in the study during the recruitment period (2000–2005). The subjects’ ethnicity and age data are similar to the data reported during the study period by the Organ Procurement and Transplant Service (OPTS) (nationally and for Sites A and Site B), that is, the majority of our subjects were white and between the ages of 50–64 years. However, unlike the OPTS report, the majority of our subjects were female (2). In 2000, when this longitudinal study was implemented, only 3.0 % of LTx recipients were ≥ 65 years so it seemed reasonable to exclude subjects who were 65 years or older. Since then, studies show that the survival of the LTx procedure does not differ significantly by age (37, 38), although elderly patients do have a higher risk of post-LTx complications (39). In 2011, OPTN reported that the percentage of LTx recipients who were ≥ 65 years of age increased to 10.9% (2).

The longitudinal nature of this study, while a strength, also presents potential limitations. Thus, the generalizability of the findings is limited temporally and to similar settings and patient populations.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is based on a project supported by Grant Number # R55-NR04283-01 and RO1-NR052841 from NIH and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. Funding from the Graduate School and the School of Nursing of University of Wisconsin-Madison, as well as the Niehoff School of Nursing and the Stritch School of Medicine, Loyola University of Chicago also supported the project. The Transplant Symptom Inventory (TSI) was developed for this study by Dorothy M. Lanuza, Cheryl A. Lefaiver, and Gabriella Farcas-Chan. The authors are grateful to the lung transplant patients who participated in this study and the nurses at Loyola University Medical Center and the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics, especially Mary McCabe, Mary Francois, and Kelly Radford who helped to implement this study.

Footnotes

Authors contributions: Lanuza, D.M.- secured funding, concept design, study implementation, data collection, analysis interpretation, article authorship; Lefaiver, C.A.- concept design, study implementation, data collection, analysis/interpretation, and co-authorship; Brown, R.- statistical analysis and interpretation, Muehrer, R.- statistical analysis/interpretation and co-authorship, Murray, M.- data collection and co-authorship, Yelle, M.- data collection and co-authorship, & Bhorade, S. – study implementation and co-author.

References

- 1.Cal J. Double and single lung transplantation: An analysis of twenty years of OPT/UNOS registry data. Clinical Transplantation. 2007:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U. S. Department of Health Resources and Services/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. [Accessed December 15, 2011.];U S Department of Health Resources and Services/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/

- 3.Dobbels F, Moons P, Abraham I, Larsen CP, Dupont L, De Geest S. Measuring symptom experience of side-effects of immunosuppressive drugs: the Modified Transplant Symptom Occurrence and Distress Scale. Transpl Int. 2008 Aug;21(8):764–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Geest S, Moons P. The patient’s appraisal of side-effects: the blind spot in quality-of-life assessments in transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000 Apr;15(4):457–459. doi: 10.1093/ndt/15.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drent G, De Geest S, Dobbels F, Kleibeuker JH, Haagsma EB. Symptom experience, nonadherence and quality of life in adult liver transplant recipients. Neth J Med. 2009 May;67(5):161–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kugler C, Fischer S, Gottlieb J, et al. Symptom experience after lung transplantation: impact on quality of life and adherence. Clin Transplant. 2007 Sep-Oct;21(5):590–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2007.00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacNaughton KL, Rodrigue JR, Cicale M, Staples EM. Health-related quality of life and symptom frequency before and after lung transplantation. Clin Transplant. 1998 Aug;12(4):320–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hegyvary ST. Patient care outcomes related to management of symptoms. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 1993;11:145–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kugler C, Strueber M, Tegtbur U, Niedermeyer J, Haverich A. Quality of life 1 year after lung transplantation. Prog Transplant. 2004 Dec;14(4):331–336. doi: 10.1177/152692480401400408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.TenVergert EM, Vermeulen KM, Geertsma A, et al. Quality of life before and after lung transplantation in patients with emphysema versus other indications. Psychol Rep. 2001 Dec;89(3):707–717. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2001.89.3.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Vito Dabbs A, Johnson BA, Wardzinski WT, Iacono AT, Studer SM. Evaluation of the electronic version of the Qustionnaire for Lung Transplant Patients. Prog Transplant. 2007;17(1):29–35. doi: 10.1177/152692480701700104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drent G, Moons P, De Geest S, Kleibeuker JH, Haagsma EB. Symptom experience associated with immunosuppressive drugs after liver transplantation in adults: possible relationship with medication non-compliance? Clin Transplant. 2008 Nov-Dec;22(6):700–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2008.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grady KL, Jalowiec A, Grusk BB, White-Williams C, Robinson JA. Symptom distress in cardiac transplant candidates. Heart Lung. 1992 Sep-Oct;21(5):434–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jalowiec A, Grady KL, White-Williams C, et al. Symptom distress three months after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1997 Jun;16(6):604–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lanuza DM, McCabe M, Norton-Rosko M, Corliss JW, Garrity E. Symptom experiences of lung transplant recipients: comparisons across gender, pretransplantation diagnosis, and type of transplantation. Heart Lung. 1999 Nov-Dec;28(6):429–437. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(99)70032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lough ME, Lindsey AM, Shinn JA, Stotts NA. Impact of symptom frequency and symptom distress on self-reported quality of life in heart transplant recipients. Heart Lung. 1987 Mar;16(2):193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodrigue JR, Baz MA, Kanasky WF, Jr, MacNaughton KL. Does lung transplantation improve health-related quality of life? The University of Florida experience. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005 Jun;24(6):755–763. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhodes VA, Watson PM. Symptom distress--the concept: past and present. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1987 Nov;3(4):242–247. doi: 10.1016/s0749-2081(87)80014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhodes VA, McDaniel RW, Homan SS, Johnson M, Madsen R. An instrument to measure symptom experience. Symptom occurrence and symptom distress. Cancer Nurs. 2000 Feb;23(1):49–54. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200002000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. European Journal of Cancer. 1994;30A(9):1326–1336. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kugler C, Geyer S, Gottlieb J, Simon A, Haverich A, Dracup K. Symptom experience after solid organ transplantation. J Psychosom Res. 2009 Feb;66(2):101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleiss JL, Chilton NW, Wallenstein S. Ridit analysis in dental clinical studies. J Dent Res. 1979 Nov;58(11):2080–2084. doi: 10.1177/00220345790580110701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moons P, De Geest S, Abraham I, Cleemput JV, Van Vanhaecke J. Symptom experience associated with maintenance immunosuppression after heart transplantation: patients’ appraisal of side effects. Heart Lung. 1998 Sep-Oct;27(5):315–325. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(98)90052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moons P, Vanrenterghem Y, Van Hooff JP, et al. Health-related quality of life and symptom experience in tacrolimus-based regimens after renal transplantation: a multicentre study. Transpl Int. 2003 Sep;16(9):653–664. doi: 10.1007/s00147-003-0595-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koller A, Denhaerynck K, Moons P, Steiger J, Bock A, De Geest S. Distress associated with adverse effects of immunosuppressive medication in kidney transplant recipients. Prog Transplant. 2010 Mar;20(1):40–46. doi: 10.1177/152692481002000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donaldson GW. Ridit scores for analysis and interpretation of ordinal pain data. Eur J Pain. 1998;2(3):221–227. doi: 10.1016/s1090-3801(98)90018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bross IDJ. How to use Ridit analysis. Biometrics. 1958;14:18–38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bross IDJ. Ridt analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1978;107:264–264. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1995;57(B):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Storey JD. A direct approach to false discovery rates. J R Statist Soc B. 2002;64(Part 3):479–498. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhorade SM, Villanueva J, Jordan A, Garrity ER., Jr Immunosuppressive regimens in lung transplant recipients. Drugs Today (Barc) 2004;40(12):1003–1012. doi: 10.1358/dot.2004.40.12.872575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bayoumi M. Identification of the Needs of Haemodialysis Patients Using the Concept of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. J Ren Care. 2012 Nov 15;38:43. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2011.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lanuza DM, Lefaiver C, Mc Cabe M, Farcas GA, Garrity E., Jr Prospective study of functional status and quality of life before and after lung transplantation. Chest. 2000 Jul;118(1):115–122. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.TenVergert EM, Essink-Bot ML, Geertsma A, van Enckevort PJ, de Boer WJ, van der Bij W. The effect of lung transplantation on health-related quality of life: a longitudinal study. Chest. 1998 Feb;113(2):358–364. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.2.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chisholm MA. Issues of adherence to immunosuppressant therapy after solid-organ transplantation. Drugs. 2002;62(4):567–575. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200262040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Vito Dabbs A, Kim Y, Vensak J, Studer S, Iacono A. Validation and refinement of the Questionnaire for Lung Transplant Patients. Prog Transplant. 2004;14(4):338–345. doi: 10.1177/152692480401400409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palmer SM, Davis RD, Simsir SA, et al. Successful bilateral lung transplant outcomes in recipients 61 years of age and older. Transplantation. 2006 Mar 27;81(6):862–865. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000203298.00475.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vadnerkar A, Toyoda Y, Crespo M, et al. Age-specific complications among lung transplant recipients 60 years and older. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;30:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gutierrez C, Al-Faifi S, Chaparro C, et al. The effect of recipient’s age on lung transplant outcome. The effect of recipient’s age on lung transplant outcome. 2007 May;7(5):1271–1277. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]