Summary

Background

Airway cilia must be physically oriented along the longitudinal tissue axis for concerted, directional motility that is essential for proper mucociliary clearance.

Results

We show that Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) signaling specifies directionality and orients respiratory cilia. Within all airway epithelial cells a conserved set of PCP proteins shows interdependent, asymmetric junctional localization; non-autonomous signaling coordinates polarization between cells; and a polarized microtubule (MT) network is likely required for asymmetric PCP protein localization. We find that basal bodies dock after polarity of PCP proteins is established, are polarized nearly simultaneously, and refinement of basal body/cilium orientation continues during airway epithelial development. Unique to mature multiciliated cells, we identify PCP-regulated, planar polarized MTs that originate from basal bodies and interact, via their plus ends, with membrane domains associated with the PCP proteins Frizzled and Dishevelled. Disruption of MTs leads to misoriented cilia.

Conclusions

A conserved PCP pathway orients airway cilia by communicating polarity information from asymmetric membrane domains at the apical junctions, through MTs, to orient the MT and actin based network of ciliary basal bodies below the apical surface.

Introduction

The pseudostratified epithelial monolayer of the upper airways comprises multiciliated cells (MCCs) and non-MCCs, including goblet and basal cells. MCCs project hundreds of cilia whose directional, concerted beating clears contaminants from the lungs. Mucociliary clearance requires uniform cilium orientation within individual cells, among neighboring cells, and along the tissue axis. Each cilium consists of a motile axoneme and a basal body that anchors it to the apical cell membrane. Cilia appear during embryogenesis; their initially uncoordinated motility becomes directional and concerted postnatally [1]. Motility defects precipitate or exacerbate airway diseases such as primary ciliary dyskinesia and asthma. Directional ciliary motion is also essential for ependymal, oviduct and embryonic node development and function.

PCP proteins regulate cilium orientation or positioning in several tissues [2]. The PCP pathway was first described in Drosophila, where it orients cuticular hairs, bristles and eye facets [3]. PCP is established by the integration of a global directional cue that defines the polarity axis; a core system that coordinates the polarity of cells with each other; and downstream effectors that control responsive morphogenetic events. To establish molecular asymmetry, the core proteins segregate into distal [Frizzled (Fz), Dishevelled (Dsh), Diego (Dgo), and Flamingo (Fmi)] and proximal [Van Gogh (Vang), Prickle (Pk) and Fmi] complexes at the cell cortex. An intercellular feedback loop across adjacent cell membranes amplifies and propagates asymmetry from cell to cell, coordinating the polarity of neighbors. Downstream factors are cell type-specific and, in some cases, modulate the cytoskeleton.

Vertebrate PCP proteins regulate polarization in both epithelial and nonepithelial cells, controlling convergent extension, bronchiolar branching and cilium, hair follicle and inner ear hair cell orientation [3]. PCP mutations produce hydrocephalus and laterality, neural tube, renal, cardiac and auditory defects. Mechanistic conservation with flies is suggested by asymmetric PCP protein localization in some tissues, but polarization mechanisms remain poorly characterized.

PCP proteins control motile cilium orientation in the embryonic Xenopus epidermis [4] and mammalian ependyma [5]. Some PCP proteins also regulate basal body docking to the apical surface during ciliogenesis [6]. Cilia are oriented both within individual cells (rotational orientation) and along the tissue axis (tissue-level orientation), and evidence suggests that PCP-mediated intercellular communication is required for proper orientation. In ependymal cells, Vangl2 was shown to localize asymmetrically [5], however the mechanism by which PCP signaling orients cilia is unexplored. In addition to PCP, cilium orientation requires directional, hydrodynamic forces generated by ciliary fluid flow, via an unknown mechanism [7].

Here, we demonstrate that airway cilia are oriented by a core PCP mechanism that controls initial polarization and subsequent refinement of cilium orientation. We also propose two functions for MTs in airway epithelial PCP. First, in an earlier function, analogous to flies [8], a polarized apical MT cytoskeleton is required in every cell for asymmetric subcellular localization of core PCP proteins. Second, specifically in MCCs, PCP-dependent, polarized MTs interact with proximal apical junctions and appear to be required to orient ciliary basal bodies distributed within a cytoskeleton network below the surface. We propose that directional information is transmitted from PCP proteins localized asymmetrically at adherens junctions, through planar polarized MTs, to basal bodies, orienting them in the direction of PCP signaling.

Results

PCP components are asymmetrically localized in the airway epithelium

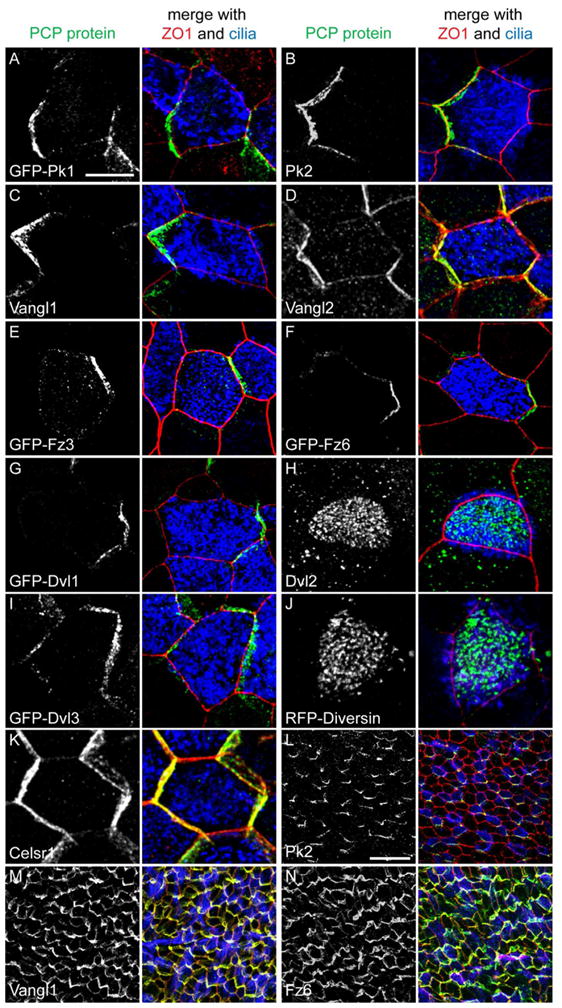

We examined PCP protein localization in fully differentiated air-liquid interface (ALI) primary cultures of mouse tracheal epithelial cells (MTEC) (Fig. S1A,B), which faithfully model the airway epithelium [9]. Consistent with other planar polarized tissues, the core PCP proteins Vang-like1 (Vangl1), Vang-like2 (Vangl2), Prickle2 (Pk2), Frizzled3 (Fz3), Frizzled6 (Fz6), Dishevelled1 (Dvl1), Dishevelled3 (Dvl3), and Celsr1 (Fmi homolog) localize asymmetrically to the cell cortex at the level of the apical junctions (a pattern commonly termed “crescent”), and Dishevelled2 (Dvl2) and Diversin (Dgo homolog) localize to the base of cilia. Prickle1 is not expressed, but GFP-Pk1 can form crescents (Fig. 1A–K). Crescents form both in MCCs and non-MCCs (not Pk2, below), although in mature MTEC antibody labeling is stronger in MCCs (Fig. 1; S1C). Dvl2 and Diversin localize to the centrosome in non-MCCs (not shown). Vangl1, Vangl2, Pk2, Fz6 are similarly asymmetric at the apical junctions in the trachea (Fig. 1L–N and not shown). Asymmetric PCP protein localization is a hallmark of planar polarized epithelia and is thought to be a functional requirement of PCP signaling, suggesting that the PCP pathway is active in the airway epithelium both in vivo and in vitro. In MTEC, although tissue-level polarity is absent, strong local alignment of cell polarities still occurs (Fig. S1D), likely reflecting the ability of the core mechanism to locally coordinate polarity even in the absence of a tissue-wide directional signal [10].

Figure 1. PCP protein localization in mouse tracheal epithelial cells.

(A–K) ALI+14 days MTEC or MTEC infected with epitope-tagged lentivirus labeled with PCP protein or epitope tag (green), ZO1 (red) and Ac. Tubulin (blue) antibody. Adult trachea wholemount labeled for Pk2 (L), Vangl1 (M) and Fz6 (N) (green), ZO1 (red) and Ac. Tubulin (blue) antibody. All trachea images are proximal (oral) side up. Scale bar, A–K, 7.5 μm; L–N, 25 μm. See Figure S1.

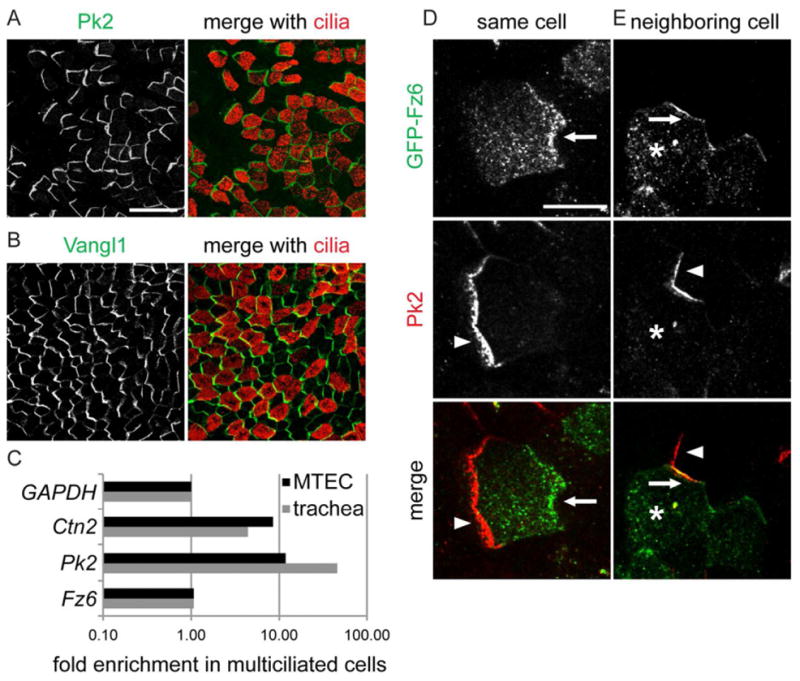

Uniquely, Pk2 is present only in MCCs in trachea and MTEC (Fig. 1B,L; 2A,B). Using RT-PCR, we found that Pk2, but not other core homologs, is enriched in MCCs (Fig. 2C and not shown). We speculate that Pk2 functions specifically in MCCs, perhaps to orient cilia, while other core PCP homologs may communicate polarity information throughout the epithelium. In contrast to other studies [5, 11], we did not detect PCP proteins in the ciliary axoneme. Our results suggest that PCP signaling is likely mediated at the apical junctions in the airway epithelium. To establish the relative localization of PCP proteins, we used the knowledge that Vangl1 [12] and Pk2 are on the distal airway (lung) side of MCCs (Fig. 1L). Within a cell, Pk2 is on the same side as GFP-Vangl1 and -Vangl2 and on the opposite side from GFP-Fz3, -Fz6, -Dvl1 and -Dvl3. The Pk2 crescent of a neighboring cell is adjacent to GFP-Fz3, -Fz6, -Dvl1 and -Dvl3, and distant from GFP-Vangl1 and -Vangl2 (Fig. 2D,E and not shown). This indirectly demonstrates that Vangl homologs and Pk2 are on the distal side, while Fz homologs, and Dvl1 and 3 are on the proximal (oral) side of airway epithelial cells. This is identical to the relationship between the fly homologs in the wing.

Figure 2. Pk2, and relative localization of PCP proteins.

MTEC labeled with Pk2 (A), Vangl1 (B) (green) and Ac. Tubulin (red) antibody. Scale bar, A,B, 25 μm. (C) Realtime PCR from ALI+14 days MTEC sorted for MCCs and non-MCCs. Ctn2 (basal body protein), Pk2, and Fz6 values normalized to GAPDH and plotted as fold enrichment in MCCs. (D and E) MTEC labeled with Pk2 antibody (red; arrowhead) and infected with GFP-Fz6 lentivirus (green; arrow) in the same (D) or an adjacent (E) (asterisk) cell. Scale bar, D,E, 7.5 μm.

PCP protein asymmetry emerges prior to ciliogenesis

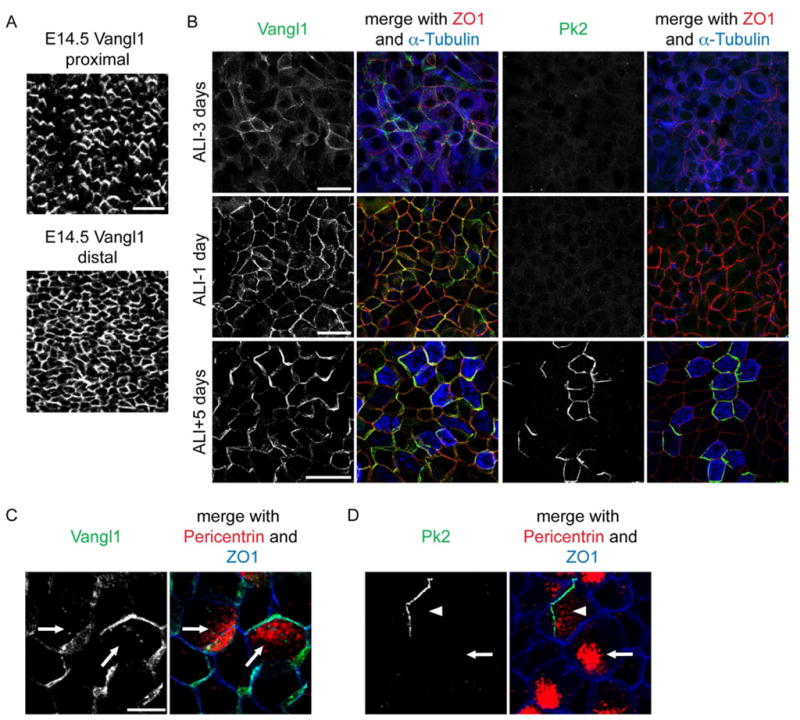

We examined the timing with which PCP protein asymmetry is acquired relative to airway epithelial differentiation and ciliogenesis (Table S1). During development, ciliogenesis spans E16.5 to P15, and directional motility begins at P9 [1]. Initially, Vangl1 and Fz6 localization is uniform at apical junctions, then rapidly becomes asymmetric by E14.5, with a delay from the proximal to the distal airways, reflecting the proximal to distal (P-D) pattern of growth and differentiation [13] (Fig. 3A). At E16.5, when cilia first appear, Vangl1 and Fz6 have already reached their maximum observed asymmetry. A similar sequence is evident during the early stages of MTEC differentiation: as cell-cell junctions start forming, PCP proteins are uniformly membrane localized, then transition, in confluent cells, to asymmetric localization. Vangl1 and Fz6 are asymmetric before nascent basal bodies appear (Fig. 3B and not shown). In contrast, Pk2 crescents first appear at E16.5 in ciliating cells. In MTEC, Pk2 crescents appear only in cells that have already generated their complement of basal bodies (Fig. 3B,D; S1B). Thus, while the asymmetric localization of Vangl1 and Fz6 prior to basal body generation and orientation suggests a possible function in establishing polarity within and between cells, the later appearance of Pk2 solely in ciliating cells suggests a function specifically in MCCs. Unlike in the fly wing and mouse ependyma, [3, 5], asymmetric localization is stably maintained throughout life in the tracheal epithelium. Motile cilia are not themselves necessary for maintaining PCP protein asymmetry (Fig. S2).

Figure 3. Progressive acquisition of PCP protein asymmetry.

(A) E14.5 trachea labeled with Vangl1 antibody; Vangl1 is localized asymmetrically in the proximal (top), but not yet in the distal region (bottom). Scale bar, 25 μm. (B) Differentiating MTEC labeled with Pk2 (right) or Vangl1 (left) (green), ZO1 (red) and α-Tubulin (blue) antibody. Scale bars, 25 μm. (C,D) Ciliating MTEC labeled with Vangl1 (C) and Pk2 (D) (green), Pericentrin (red) and ZO1 (blue) antibody; nascent basal body clusters (C,D; arrows, always abut Vangl1); docked basal bodies (D; arrowhead). Scale bar, C,D, 10 μm. See Figure S2 and Table S1.

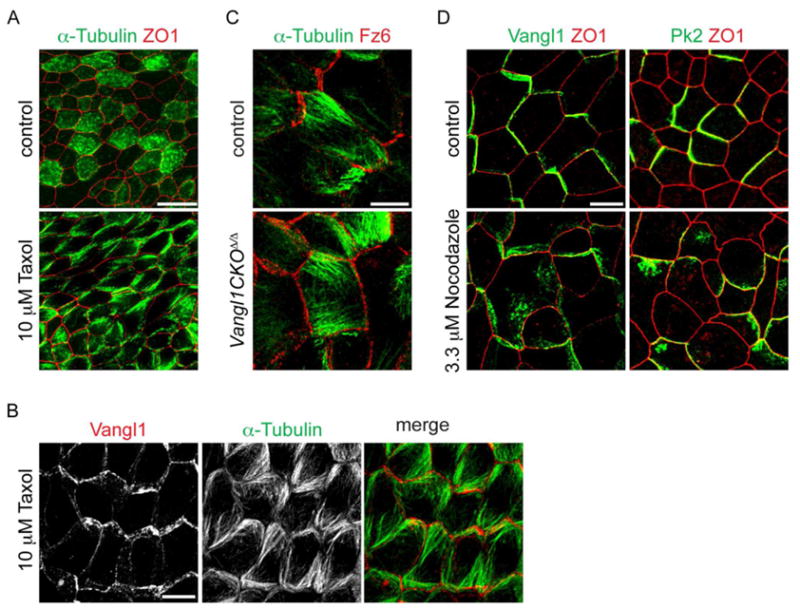

In flies, asymmetric core PCP protein localization is proposed to require directed vesicular transport on planar polarized microtubules (MTs) [8, 14]. Thus, we explored the role of MTs in airway PCP acquisition. When PCP protein asymmetry emerges, we observe apical, polarized MTs in MTEC using anti-α Tubulin antibody labeling (Fig. S3A), though ciliary and other cytoplasmic MTs obscure their visualization. However, after we block ciliogenesis with the MT-stabilizing drug Taxol, we clearly observe planar polarized MT bundles in nearly all cells during PCP establishment (Fig. 4A,B; S3B). As in flies [8], these MTs are unaffected in PCP mutant MTEC in which polarity of core PCP proteins is disrupted (Fig. 4C, S3C). In MTEC treated with the MT-depolymerizing drug Nocodazole, PCP proteins fail to completely target to the apical junctions and sometimes accumulate near the membrane (Fig. 4D, Taxol had no effect, not shown). By analogy with flies, these data suggest that P-D oriented MTs may participate in targeting PCP proteins to the proper membrane domains in airway epithelial cells.

Figure 4. Polarized MTs in airway epithelial cells.

(A) ALI+2 days MTEC treated with 10 μM Taxol for 24 h and labeled with α-Tubulin (green) and ZO1 (red) antibody. Intense signal in some control cells due to accumulation of cytoplasmic MTs in ciliating cells. Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) ALI+2 days MTEC treated with 10 μM Taxol for 24 h labeled with α-Tubulin (green) and Vangl1 (red) antibody. Image is the maximum projection of two consecutive confocal slices selected to show parallel MTs in the central cells. (C) ALI+2 days control and Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ MTEC treated with 10 μM Taxol for 24 h and labeled with -α Tubulin (green) and Fz6 (red) antibody. (D) ALI+2 days MTEC treated with 3.3 μM Nocodazole for 24 h and labeled with Vangl1 (left) or Pk2 (right) (green) and ZO1 (red) antibody. Scale bar, B–D, 7.5 μm. See Figure S3.

Acquisition of cilium polarity during airway development

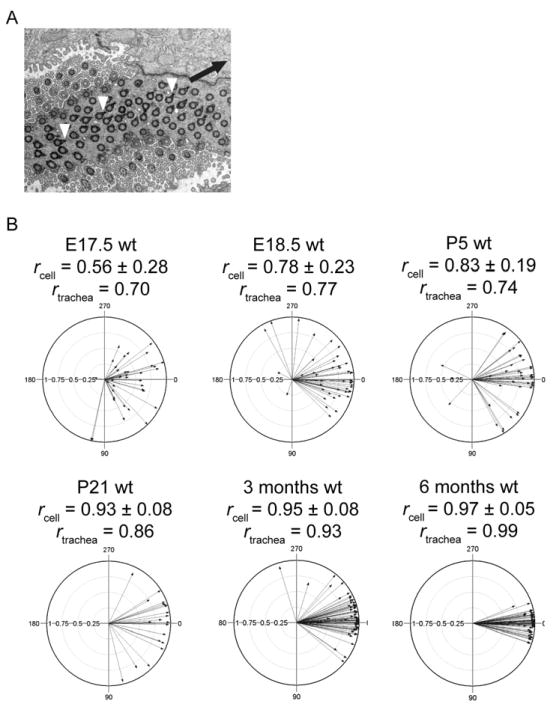

Our results indicate that ciliogenesis occurs in a molecularly planar polarized epithelium. To examine the onset and kinetics of cilium orientation with respect to the emergence of molecular polarity, we measured the orientation of basal feet, basal body appendages that point in the direction of the active stroke, in tracheal TEM cross sections (Fig. 5A). Mean cellular basal foot orientation (rotational orientation) was plotted as a vector with length indicating the uniformity of basal foot orientation (rcell) and tissue-level cilium orientation (rtrachea) was calculated as the average of the cellular mean vectors (Fig. 5B; S4). Immediately upon docking, basal bodies show significant polarity in the proximal (oral) direction. As in other multiciliated epithelia, both rotational and tissue-level cilium polarity refines gradually (Fig. 5B; S4). In other tissues, refinement requires both PCP and directional, ciliary motility-driven fluid flow [7]. Here, we observe substantial refinement before tissue-wide, directional ciliary fluid flow is reported to start at P9 [1]. Additional experiments will be necessary to determine potential contributions of physical forces, including those from uncoordinated local ciliary beating. The timing of molecular and cilium polarization in the airway epithelium is consistent with PCP signaling contributing to initial cilium orientation. MCC polarity was also apparent in the asymmetric placement of the basal body cluster in ciliating cells (Fig. 3C), however the functional relationship between this and future cilium orientation remains unknown.

Figure 5. Refinement of basal body orientation.

(A) TEM of P5 trachea with proximally (arrow) pointing basal feet (arrowheads). All basal bodies appear as cylinders in cross section, indicating they have docked. (B) Circular plots of basal body orientation. Arrow direction represents the mean vector of cilium orientation per cell (proximal direction set at 0°), and arrow length is the length of the mean vector, with longer arrows indicating stronger coordination of orientation. rcell ± SE is the length of the mean vector and describes rotational orientation. rtrachea describes tissue-level orientation. See Figure S4.

Cilium orientation defects in PCP mutant airway epithelium

We found the previously reported Vangl1gt/gt mice [15] to have profound tissue-level cilium orientation defects compared to wildtype littermates (Fig. S5A, rtrachea of 0.14 vs. 0.99). Rotational polarity defects are also present, although much less severe (rcell of 0.82 ± 0.16 vs. 0.97 ± 0.05, p < 1E-09). Unfortunately, the extremely poor viability of these mice prevented characterization of late embryonic and postnatal PCP events. Thus, we generated a conditional allele, Vangl1CKO, that deletes the transmembrane domains in exon 4, producing a truncated, in frame transcript. Homozygous deleted Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ mice are viable, fertile and born in the expected Mendelian ratio with no externally evident developmental defects.

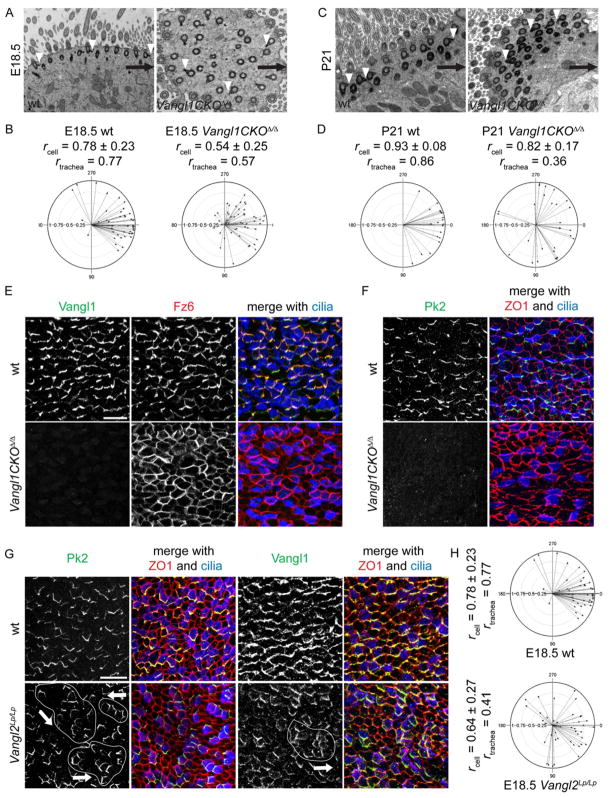

Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ mutants also have a fully penetrant PCP defect, mostly affecting tissue-wide cilium polarity (Fig. 6A–D, Fig. S5A). Cilium misorientation is somewhat less severe than in Vangl1gt/gt mice, suggesting that the Vangl1CKO allele is hypomorphic (Fig. S5A). At E18.5, Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ mutants display rotational (rcell of 0.54 ± 0.25 vs. 0.78 ± 0.23, p < 4E-06) and tissue-level (rtrachea of 0.57 vs. 0.77) cilium misorientation compared to wildtype. Rotational orientation, as in wildtype, refines slightly during development, however, tissue-level orientation deteriorates (Fig. 6A–D, Fig. S5A). We propose that the predominant effect of Vangl1 mutants on tissue-level polarity reflects the function of the PCP mechanism to orient the entire network of basal bodies in a given cell en bloc (see below). Thick mucus covers the Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ tracheal lumen, confirming that poorly coordinated cilium orientation leads to mucociliary clearance defects (Fig. S5F). Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ airways have necrotic cells and fewer MCCs, with some of the remaining MCCs displaying shorter, sparser, although ultrastructurally normal cilia (Fig. S5G–I and not shown). Cilia are similarly affected in Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ MTEC (Fig. S5J). Some PCP proteins have previously been implicated in ciliogenesis [6], and our results indicate that the Vangl1CKO mutation has a mild effect on cilium formation.

Figure 6. Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ and Vangl2Lp/Lp mice have cilium polarity defects.

(A,C) TEM of trachea from Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ (right) and wildtype (left) littermates at E18.5 (A) and P21 (C). Arrows, proximal direction; arrowheads, basal feet. (B,D) Circular plots of cilium orientation in Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ (right) and wildtype (left) at E18.5 (B) and P21 (D). (E) Trachea from Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ (bottom) and wildtype (top) littermates labeled with Vangl1 (green), Fz6 (red) and Ac. Tubulin (blue) antibody. (F) Trachea from Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ (bottom) and wildtype (top) littermates labeled with Pk2 (green), ZO1 (red) and Ac. Tubulin (blue) antibody. Scale bar, E–F, 25 μm. (G) Trachea from Vangl2Lp/Lp (bottom) and wildtype (top) littermates labeled with Pk2 (left) or Vangl1 (right) (green), ZO1 (red) and Ac. Tubulin (blue) antibody. Areas of locally coordinated cell polarity in the mutant are outlined; arrows show direction of polarization. Scale bar, 50 μm. (H) Circular plots of cilium orientation in Vangl2Lp/Lp (bottom) and wildtype (top) at E18.5. See Figure S5.

Cilium misorientation is reflected in underlying changes in PCP protein distribution in Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ mice and MTEC. Vangl2 is dramatically reduced, Fz6 and Celsr1 asymmetry at the membrane is reduced, and Pk2 is absent. Dvl2 is unperturbed at the base of cilia. (Fig. 6E,F; S5K-M and not shown). Therefore, Vangl1 is required for the recruitment and/or stable maintenance of Pk2 and Vangl2, and for restricting Celsr1 and Fz6 to their asymmetric membrane domains. Hence, as in other epithelia, interactions among PCP proteins are needed to achieve stable assembly into appropriate membrane domains.

Mice mutant for the other Vang-like homolog, Vangl2, die at E18.5 with multiple PCP defects [16]. Unlike in Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ mice, asymmetric junctional Pk2, Vangl1 and Fz6 crescents are present in individual Vangl2Lp/Lp airway epithelial cells but, while locally oriented in clusters of cells, they point in varying directions, indicating failure of tissue-level orientation (Fig. 6G and not shown). Both rotational and tissue-level orientation defects were detected in Vangl2Lp/Lp compared to wildtype (Fig. 6H, rcell 0.64 ± 0.27 vs. 0.78 ± 0.23, p < 9E-03; rtrachea 0.41 vs. 0.77). Vangl1CKO+/Δ; Vangl2+/Lp mice also showed loss of tissue level coordination of PCP crescents (Fig. S5N). These results indicate that Vangl1 and Vangl2 regulate cilium PCP together.

Role of the microtubule cytoskeleton in motile cilium orientation

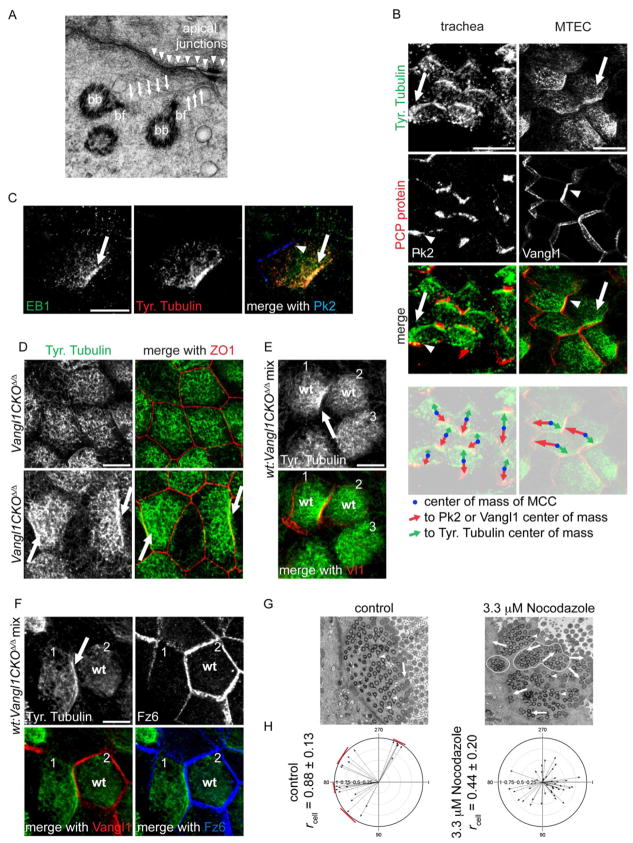

An actin and MT network connects neighboring basal bodies, imparting regular spacing and coordinated rotational orientation to cilia within a MCC [12, 17–19]. The observation that Vangl1 mutants have much more severe tissue-level than rotational misorientation (Fig. 6B,D; S5A), raises the possibility that the PCP mechanism polarizes cilia by orienting the network of internally aligned basal bodies within each cell to a region of the cell cortex defined by the asymmetric accumulation of PCP components. Because the PCP system is known to organize cytoskeletal elements in other contexts [8, 14, 20, 21], we sought clues to whether PCP-driven cytoskeletal organization orients airway cilia along the trachea. Indeed, in TEM sections showing basal bodies near the membrane, we detected MTs, similar to those that span neighboring basal bodies (Fig. S6A), but instead extending from the basal feet toward the proximal (oral) side apical junctions (Fig. 7A). We hypothesize that these MTs may represent a direct link between the basal body layer and the PCP crescent at the cell cortex and thus may orient cilia to the tissue-wide PCP signal.

Figure 7. Planar polarized tyr-MTs and cilium orientation.

(A) TEM of a MCC from adult trachea (MTs, arrows; basal foot, bf; basal bodies, bb; apical junctions, arrowheads). (B) Adult trachea (left) and ALI+14 days MTEC (right) labeled with Tyr. Tubulin (green) and Pk2 (trachea) or Vangl1 (MTEC) (red) antibody (Tyr. Tubulin, arrow; Pk2 or Vangl1, arrowhead). The merged images were overlayed with a schematic showing the center of mass for each MCC (blue dot) and arrows pointing to the center of mass of the Tyr. Tubulin (green arrow) and the Pk2 or Vangl1 (red arrow) signals. Scale bars, left, 25 μm; right, 10 μm. (C) MTEC labeled with EB1 (green), Tyr. Tubulin (red) and Pk2 (blue) antibody (EB1, arrow; Pk2, arrowhead). Basal body signal from EB1 is not captured in this section. Scale bar, 7.5 μm. (D) Mature Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ MTEC labeled with Tyr. Tubulin (green) and ZO1 (red) (Tyr. Tubulin on random sides of cells, arrows). (E,F) MTEC generated from a mixture of Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ and wildtype cells. Presence or absence of Vangl1 signal differentiates between wildtype and Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ cells, wildtype cells marked (wt), all other cells are mutant. (E) MTEC labeled with Tyr. Tubulin (green) and Vangl1 (red). Tyr-tub (arrow) forms only in a cell (cell1) that has a wt neighbor (cell2). (F) MTEC labeled with Tyr. Tubulin (green), Vangl1 (red) and Fz6 (blue). Tyr-tub (arrow) forms only in cells with asymmetric Fz6 (bottom right panel, cell1). Scale bar, D–F, 7.5 μm, MTEC at ALI+14 days. (G) TEM of basal bodies in control (left) and Nocodazole-treated (right) MTEC (basal feet, arrowheads, arrows show polarization direction; clusters outlined). ALI+14 days MTEC were treated with 3.3 μM Nocodazole for 24 h. (H) Circular plots of cilium orientation in control (left) and Nocodazole-treated (right) MTEC. Clustering of mean angles in neighboring control cells (red bars) is due to intercellular coordination (see Fig. S1D). See Figure S6.

To study these cortex-associated MTs, we visualized them at the light level. In mature MTEC and adult trachea, anti-Tyrosinated α-Tubulin antibody labeling (marking newly synthesized MT plus-ends) revealed an enrichment of tyrosinated MTs (tyr-MTs) at proximal-side apical junctions, exclusively in MCCs (Fig. 7B). Tyr-tub crescents are first observed around the time of basal body docking and are less tightly associated with the cortex than PCP proteins (Fig. S6B). Glu Tubulin is not asymmetrically localized (Fig. S6C). Tyr-tub can recruit MT plus-end binding proteins (+TIPs) [22], which can mediate the interaction of MTs with the cortex [23]. Consistently, the +TIPs EB1, APC, p150Glued/Dynactin and STIM1 colocalize with tyr-MTs at the junctions (Fig. 7C; S6D–E). The tyr-tub signal, therefore, appears to represent MTs with plus ends contacting the apical junctions, and likely marks the same population of MTs that were observed by EM (Fig. 7A). We propose that they link the periphery of the basal body layer to the proximal side Fz/Dvl domain, thereby orienting all of the cilia in a given MCC to the tissue-wide direction of polarity.

We asked whether PCP controls the tyr-MTs. Tyr-tub was not asymmetric in most Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ MTEC, and where it was asymmetric, it did not accumulate on the same side in neighboring cells (Fig. 7D; S6F), paralleling the strong tissue-level cilium misorientation in mature Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ trachea (Fig. S5A). Strikingly, tyr-tub asymmetry depends on Vangl1 in a non-cell-autonomous fashion: in mixed MTEC cultures derived from wildtype and Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ trachea, tyr-tub crescents can form in both wildtype and mutant cells, but only if the cell has a wildtype neighbor (Fig. 7E,F; S6G). The interface with the wildtype neighbor defines the location of the tyr-tub crescent. Furthermore, Fz6 crescents always coincide with tyr-tub crescents (Fig. 7F), suggesting that the accumulation of asymmetric tyr-MTs directly depends on an asymmetric Fz6 domain established by interaction with Vangl1 in an adjacent cell. Similar, directional, non-autonomous effects, stemming from the activity of core PCP proteins in opposing, asymmetric junctional domains, are characteristic features of planar polarized tissues [3].

To test the role of MTs in cilium orientation, we depolymerized cytoplasmic MTs in mature MTEC with Nocodazole. This did not affect ciliary MTs nor substantially disrupt PCP protein crescents, as it does in young MTEC (Fig. S6H,I; 4D). Basal bodies in Nocodazole-treated cells were no longer evenly spaced and had decreased rotational polarity (Fig. 7G,H; S6J, rcell = 0.44 ± 0.20 vs. 0.88 ± 0.13, p < 8E-16), suggesting a partial disruption of the cytoskeletal network that links and orients basal bodies to each other. Importantly, tissue-level polarity was severely disrupted, as evidenced by the loss of local, intercellular alignment that occurs in MTEC (Fig. S1D), shown by increased dispersion of the mean cellular vectors among neighboring cells. These observations reveal that MTs not only participate in orienting and spacing basal bodies within a network in each cell, but that they also contribute to orienting the basal body layer to the P-D polarity axis. We propose that the tyr-MTs we observed, that are specific to MCCs, appear only when cilia are present, and are positioned non-autonomously by the PCP system, fulfill this role.

Discussion

A conserved PCP pathway, with unique features, polarizes airway epithelial cells

This report demonstrates that a remarkably well conserved PCP pathway orients airway cilia. In both Drosophila and the mouse airways, planar polarization requires a conserved set of core PCP proteins that display hallmark, interdependent, asymmetric junctional localization [24–26], acts non-autonomously, and requires planar polarized MTs for asymmetric PCP protein localization.

Nonetheless, some surprising features are revealed. While Dvl1 and 3 localize in crescents, Dvl2 is only at basal bodies, suggesting divergent functions. Pk2 is expressed exclusively in MCCs, and only after other core PCP proteins have reached the maximal observed degree of asymmetry; Pk2, therefore, seems dispensable for the asymmetric localization of core components or for intercellular polarity communication. Instead, Pk2 likely functions only within MCCs, perhaps to polarize cilia. This contrasts with the fly, where Pk is expressed in every wing cell and pk (or pk-sple) null cells do not polarize correctly [27]. While we do not detect Pk1 or Pk2 expression when other core PCP proteins are polarizing, additional, uncharacterized Pk-related proteins (LMO6/Pk3 and Pk4) have yet to be examined, leaving open the possibility that they participate in molecular polarization.

We have analyzed the contributions of Vangl1 and Vangl2 to airway PCP. We found that, similar to other tissues [15, 28, 29], they have overlapping but distinct functions. As Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ and Vangl2Lp/Lp mice each show misoriented cilia, they are not fully redundant. Loss of Vangl2 did not randomize polarity, though the Vangl2Lp allele is not a null [30]. The hypomorphic character of the Vangl1CKOΔ allele, together with the non-viability of double mutants, also hampers determining the extent of potential overlapping functions.

PCP and cilia

The relationship between cilia and PCP is unclear, and a role for cilia in PCP signal transduction remains weakly supported [6]. Although Vangl2 has been observed in motile axonemes [5, 11], neither our proven specific antibodies nor GFP-tagged constructs detected such localization for PCP proteins. As in frogs, where Dvl2 is required for basal body docking and orientation, we observed Dvl2 with Diversin at the base of cilia [21, 31], in addition to crescents of Dvl1 and 3 at apical junctions. The presence of junctional and basal body pools suggests that Dvls may participate in two distinct mechanisms that regulate cilium polarity.

We observed short, sparse cilia in some Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ MCCs, indicating that Vangl1 may participate in cilium formation or maintenance. Reports on the role of Vang homologs in ciliogenesis vary from no [5, 16, 29] to a modest effect [4] on cilia. Unlike Inturned, Dvl2 and Celsr, which control basal body docking [6], Vangl1 may be required for cilium maintenance since basal bodies are docked and Dvl2 is properly localized in Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ mutants.

PCP and acquisition of ciliary polarity during airway development

The presence of asymmetric PCP proteins before ciliogenesis demonstrates that polarizing cues already exist when basal bodies dock. Indeed, we detect an immediate polar bias of cilium orientation at E17.5. Thus, basal bodies begin to polarize either before or immediately upon contact with the apical surface (Dvl2, a factor in both docking and orientation, is at basal bodies prior to docking). A similar bias of basal body polarity was demonstrated in the ciliating frog epithelium [32], but in the ependyma, a population of most recently docked basal bodies showed disordered orientation [5].

Following docking, basal body orientation is progressively refined. As in other multiciliated epithelia [5, 32], hydrodynamic forces generated by cilium-driven fluid flow may contribute to refinement, although substantial refinement occurs between E17.5 and P5 prior to the reported onset of tissue-wide, directional ciliary fluid flow. Overlapping with this time is rhythmic, P-D directional fluid flow generated by fetal breathing movements [33] that may also affect cilium orientation.

Microtubules as effectors of basal body polarization

The involvement of MTs in planar polarization has been firmly established [8, 14, 20, 34–36]. Our data suggest that planar polarized MTs act in airway epithelial PCP in two contexts: (1) by analogy to flies, they act in every cell to facilitate trafficking of PCP proteins to generate asymmetry, and (2) later, tyr-MTs interact with and orient basal body networks in MCCs.

In the fly wing, a P-D oriented MT array provides tracks for Fz-containing vesicles to traffic preferentially toward the distal cortex [8, 14]. We find a similarly polarized apical MT cytoskeleton in MTEC. As in Drosophila, where the MTs are organized independently of core PCP proteins, they are unperturbed in Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ MTEC, and MT disruption impairs asymmetric PCP protein localization. These observations suggest the conservation of a directionally biased, MT-based transport mechanism. Future studies of the regulation and function of these MTs will be a high priority.

Apical actin and MTs that connect neighboring basal bodies and thus direct cilium spacing and orientation have been widely documented in MCCs [12, 18, 19, 37]. These linkages could polarize cilia with respect to each other, but an additional mechanism is needed to orient them along the tissue axis. We propose that MTs linking the basal body layer to the Fz/Dvl crescent at the proximal side junctions impart tissue level polarity to cilia. Although our approaches so far have yet to directly demonstrate that the observed population of tyr-MTs orients cilia, our hypothesis is bolstered by several lines of evidence, including their appearance specifically in MCCs at the time of basal body docking, their dependence on the PCP pathway and, most importantly, by the concordance between the effect on tyr-MTs and the basal body orientation defect in Vangl1 mutant mice. Consistent with the substantial tissue-level, but only slight rotational cilium misorientation in Vangl1 mutants, we propose that PCP-dependent tyr-MTs are necessary for tissue-level orientation separate from the cytoskeletal elements that impart rotational polarity.

Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ mosaic experiments demonstrate that the asymmetric accumulation and placement of junctional tyr-tub and Fz6 each depend on contact with a neighboring cell that assembles a Vangl1-containing complex at the interface, but do not depend on Vangl1 cell-autonomously. We propose that intercellular interaction, likely mediated by Celsr [3], communicates the presence of these complexes between neighboring cells. Fz and Dvl regulate MT dynamics in multiple planar polarized systems [38], and may organize the tyr-MTs in MCCs. Given that Fz/Dvl crescents are present in all airway epithelial cells, additional factors that trigger the formation of asymmetric tyr-MTs in MCCs will need to be identified.

The proximal junctional accumulation of +TIPs suggests that tyr-MTs are interacting with the cortex at or near the Fz/Dvl crescent. This implies an intriguing parallel to oriented cell division in several systems in which astral MTs emanating from spindle poles are captured and anchored to a distinct cortical domain by +TIPs to specify the division axis. MT dynamics and cortical motors provide force to reorient MTs and refine spindle position [39]. In MCCs, a similar force may produce an increasingly polarized MT network, thus contributing to the refinement of basal body orientation during airway PCP acquisition.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Vangl1CKOΔ/Δ mice (Fig. S5) were created by mating to the HPRT::Cre deleter line (JAX). Vangl1gt [15] and Vangl2Lp (JAX) mice have been previously described. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for additional mouse lines and unpublished genotyping methods. All procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with established guidelines for animal care.

MTEC culture, lentiviral infection and microscopy

MTEC culture and lentiviral infection were performed as previously described [9, 40]. MTEC and tracheas were processed for immunofluorescence and electron microscopy using standard methods. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

Measurement of basal body orientation

MCC polarity was assessed as previously described [4], see Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details. Circular plots for some wildtype mice are displayed once in the developmental timeline (Fig. 5) and again to compare with mutant littermates (Fig. 6; S5). Data for these figures were derived by crossing Vangl1CKO+/Δ;Vangl2+/Lp or Vangl1CKO+/Δ;Vangl1+/gt mice to produce all necessary genotypes.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

PCP proteins are asymmetric at apical junctions in the airways before ciliogenesis.

PCP protein asymmetry and cilium orientation emerge gradually during development.

Cilium misorientation correlates with loss of PCP protein asymmetry in PCP mutants.

Microtubules appear to organize cilium orientation and PCP protein asymmetry.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tushar Desai, Jill Helms and Larry Ostrowski for mice; Mike Deans for the Vangl2Lp genotyping protocol; Elaine Fuchs, Mireille Montcouquiol and Angela Barth for antibodies; Jeremy Nathans, Anthony Wynshaw-Boris and Sergei Sokol for cDNAs; Patrick Bogard for help with MTEC studies; Klara Fekete and Hermie Manuel for help with animal husbandry; and John Perrino and Lydia Joubert for help with EM. Work was supported by an AP Giannini Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship to EKV, R01 GM059823 and R01 GM098582 to JDA. MPS is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Author contributions

EKV designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the paper; EKV, RDB, AS, and MPS generated the Vangl1CKO mouse line; and JDA supervised the design and analysis of the experiments. All authors edited the paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Francis RJ, Chatterjee B, Loges NT, Zentgraf H, Omran H, Lo CW. Initiation and maturation of cilia-generated flow in newborn and postnatal mouse airway. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2009;296:L1067–1075. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00001.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayly R, Axelrod JD. Pointing in the right direction: new developments in the field of planar cell polarity. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:385–391. doi: 10.1038/nrg2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodrich LV, Strutt D. Principles of planar polarity in animal development. Development. 2011;138:1877–1892. doi: 10.1242/dev.054080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell B, Stubbs JL, Huisman F, Taborek P, Yu C, Kintner C. The PCP pathway instructs the planar orientation of ciliated cells in the Xenopus larval skin. Curr Biol. 2009;19:924–929. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guirao B, Meunier A, Mortaud S, Aguilar A, Corsi JM, Strehl L, Hirota Y, Desoeuvre A, Boutin C, Han YG, et al. Coupling between hydrodynamic forces and planar cell polarity orients mammalian motile cilia. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:341–350. doi: 10.1038/ncb2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallingford JB, Mitchell B. Strange as it may seem: the many links between Wnt signaling, planar cell polarity, and cilia. Genes Dev. 2011;25:201–213. doi: 10.1101/gad.2008011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallingford JB. Planar cell polarity signaling, cilia and polarized ciliary beating. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimada Y, Yonemura S, Ohkura H, Strutt D, Uemura T. Polarized transport of Frizzled along the planar microtubule arrays in Drosophila wing epithelium. Dev Cell. 2006;10:209–222. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.You Y, Richer EJ, Huang T, Brody SL. Growth and differentiation of mouse tracheal epithelial cells: selection of a proliferative population. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L1315–1321. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00169.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma D, Yang CH, McNeill H, Simon MA, Axelrod JD. Fidelity in planar cell polarity signalling. Nature. 2003;421:543–547. doi: 10.1038/nature01366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross AJ, May-Simera H, Eichers ER, Kai M, Hill J, Jagger DJ, Leitch CC, Chapple JP, Munro PM, Fisher S, et al. Disruption of Bardet-Biedl syndrome ciliary proteins perturbs planar cell polarity in vertebrates. Nature genetics. 2005;37:1135–1140. doi: 10.1038/ng1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunimoto K, Yamazaki Y, Nishida T, Shinohara K, Ishikawa H, Hasegawa T, Okanoue T, Hamada H, Noda T, Tamura A, et al. Coordinated ciliary beating requires Odf2-mediated polarization of basal bodies via basal feet. Cell. 2012;148:189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toskala E, Smiley-Jewell SM, Wong VJ, King D, Plopper CG. Temporal and spatial distribution of ciliogenesis in the tracheobronchial airways of mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L454–459. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00036.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harumoto T, Ito M, Shimada Y, Kobayashi TJ, Ueda HR, Lu B, Uemura T. Atypical cadherins Dachsous and Fat control dynamics of noncentrosomal microtubules in planar cell polarity. Developmental cell. 2010;19:389–401. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antic D, Stubbs JL, Suyama K, Kintner C, Scott MP, Axelrod JD. Planar cell polarity enables posterior localization of nodal cilia and left-right axis determination during mouse and Xenopus embryogenesis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montcouquiol M, Rachel RA, Lanford PJ, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Kelley MW. Identification of Vangl2 and Scrb1 as planar polarity genes in mammals. Nature. 2003;423:173–177. doi: 10.1038/nature01618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemullois M, Boisvieux-Ulrich E, Laine MC, Chailley B, Sandoz D. Development and functions of the cytoskeleton during ciliogenesis in metazoa. Biol Cell. 1988;63:195–208. doi: 10.1016/0248-4900(88)90058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reed W, Avolio J, Satir P. The cytoskeleton of the apical border of the lateral cells of freshwater mussel gill: structural integration of microtubule and actin filament-based organelles. Journal of cell science. 1984;68:1–33. doi: 10.1242/jcs.68.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Werner ME, Hwang P, Huisman F, Taborek P, Yu CC, Mitchell BJ. Actin and microtubules drive differential aspects of planar cell polarity in multiciliated cells. The Journal of cell biology. 2011;195:19–26. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201106110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y, Stump RJ, Lovicu FJ, Shimono A, McAvoy JW. Wnt signaling is required for organization of the lens fiber cell cytoskeleton and development of lens three-dimensional architecture. Dev Biol. 2008;324:161–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park TJ, Mitchell BJ, Abitua PB, Kintner C, Wallingford JB. Dishevelled controls apical docking and planar polarization of basal bodies in ciliated epithelial cells. Nat Genet. 2008;40:871–879. doi: 10.1038/ng.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peris L, Thery M, Faure J, Saoudi Y, Lafanechere L, Chilton JK, Gordon-Weeks P, Galjart N, Bornens M, Wordeman L, et al. Tubulin tyrosination is a major factor affecting the recruitment of CAP-Gly proteins at microtubule plus ends. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:839–849. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Tsukita S. “Search-and-capture” of microtubules through plus-end-binding proteins (+TIPs) J Biochem. 2003;134:321–326. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenny A, Darken RS, Wilson PA, Mlodzik M. Prickle and Strabismus form a functional complex to generate a correct axis during planar cell polarity signaling. Embo J. 2003;22:4409–4420. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bastock R, Strutt H, Strutt D. Strabismus is asymmetrically localised and binds to Prickle and Dishevelled during Drosophila planar polarity patterning. Development. 2003;130:3007–3014. doi: 10.1242/dev.00526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strutt DI. Asymmetric localization of frizzled and the establishment of cell polarity in the Drosophila wing. Mol Cell. 2001;7:367–375. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tree DR, Shulman JM, Rousset R, Scott MP, Gubb D, Axelrod JD. Prickle mediates feedback amplification to generate asymmetric planar cell polarity signaling. Cell. 2002;109:371–381. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00715-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torban E, Patenaude AM, Leclerc S, Rakowiecki S, Gauthier S, Andelfinger G, Epstein DJ, Gros P. Genetic interaction between members of the Vangl family causes neural tube defects in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:3449–3454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712126105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song H, Hu J, Chen W, Elliott G, Andre P, Gao B, Yang Y. Planar cell polarity breaks bilateral symmetry by controlling ciliary positioning. Nature. 2010;466:378–382. doi: 10.1038/nature09129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yin H, Copley CO, Goodrich LV, Deans MR. Comparison of phenotypes between different vangl2 mutants demonstrates dominant effects of the Looptail mutation during hair cell development. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yasunaga T, Itoh K, Sokol SY. Regulation of basal body and ciliary functions by Diversin. Mech Dev. 2011;128:376–386. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell B, Jacobs R, Li J, Chien S, Kintner C. A positive feedback mechanism governs the polarity and motion of motile cilia. Nature. 2007;447:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature05771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fortin G, Thoby-Brisson M. Embryonic emergence of the respiratory rhythm generator. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;168:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eaton S, Wepf R, Simons K. Roles for Rac1 and Cdc42 in planar polarization and hair outgrowth in the wing of Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1277–1289. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.5.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sepich DS, Usmani M, Pawlicki S, Solnica-Krezel L. Wnt/PCP signaling controls intracellular position of MTOCs during gastrulation convergence and extension movements. Development. 2011;138:543–552. doi: 10.1242/dev.053959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner CM, Adler PN. Distinct roles for the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons in the morphogenesis of epidermal hairs during wing development in Drosophila. Mech Dev. 1998;70:181–192. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gordon RE. Three-dimensional organization of microtubules and microfilaments of the basal body apparatus of ciliated respiratory epithelium. Cell Motil. 1982;2:385–391. doi: 10.1002/cm.970020407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao C, Chen YG. Dishevelled: The hub of Wnt signaling. Cell Signal. 2010;22:717–727. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahringer J. Control of cell polarity and mitotic spindle positioning in animal cells. Current opinion in cell biology. 2003;15:73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vladar EK, Stearns T. Molecular characterization of centriole assembly in ciliated epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:31–42. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.