Abstract

Elevated blood pressure (BP) and infiltration of the vasculature by monocytes contribute to vascular pathology; but, monocyte migratory characteristics based on differing inflammatory potential under adrenergic activation remains unclear. We compared nonclassical (CD14+CD16++; HLA-DR+), intermediate (CD14++CD16+; HLA-DR++), and classical (CD14++CD16−; HLA-DR+/−) monocyte trafficking and their LPS-stimulated TNF production in response to a physical stressor (20-min treadmill exercise at 65-70% VO2peak) in participants with high prehypertension (PHT), mild PHT or normal BP (NBP). To determine adrenergic receptor (AR) sensitivity, pre-exercise cells were also treated with isoproterenol (Iso). When cells were stimulated with LPS, the CD16 molecules were downregulated, and monocytes subsets were differentiated based on HLA-DR expression. Monocyte subpopulations (as % of total monocytes) and intracellular TNF production were evaluated by flow cytometry. TNF production in all subsets decreased post-exercise and with ex-vivo incubation with Iso, irrespective of BP (p < .001), with nonclassical and intermediate monocytes being a major source of TNF production. Overall, % nonclassical monocytes increased, % intermediate did not change, whereas % classical decreased post-exercise (p < .001). However, % increase in nonclassical monocytes under exercise-induced adrenergic activation was blunted in high PHT individuals (p < .05), but not in individuals with mild PHT and NBP. These findings extend our previous reports by showing that the mobilization of proinflammatory monocytes under physical stress is attenuated with even mild BP elevation. This may be indicative of monocytic AR desensitization and/or greater adhesion of “proinflammatory” monocytes to the vascular endothelium in hypertension with potential clinical implications of vascular pathology.

Keywords: CD16+ monocytes, LPS-stimulated TNF production, Mobilization, Monocyte subsets, Prehypertension, Sympathoadrenergic activation, Treadmill exercise

1. Introduction

High blood pressure (BP) is a major risk factor for developing cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2002; Marinou et al., 2010). Atherosclerosis is a chronic, vascular inflammatory disease where endothelial inflammation and migration of immune cells, such as monocytes, to the inflamed endothelium play an important role in its pathogenesis. While the normal function of monocytes are tissue healing, clearance of pathogens and dead cells, and initiation of adaptive immunity (Ingersoll et al., 2011), they also substantially contribute to vascular inflammation. Monocyte mobilization, recruitment, infiltration, and inflammatory cytokine production (such as tumor necrosis factor [TNF]) are prominently involved in initiation, progression, and complication of the atherosclerotic lesions (Branen et al., 2004; McKellar et al., 2009; Skoog et al., 2002). Elevated BP also contributes to the atherogenic processes through physical damage of the arteries and endothelial inflammation (Khder et al., 1998). However, monocyte migratory characteristics based on differing inflammatory potential (i.e. monocyte subsets with differing inflammatory cytokine production) in hypertension are largely unknown.

Based on the expression levels of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) receptor CD14 and the FcγIII receptor CD16, human monocytes are divided into three major subsets: “classical” CD14++CD16−, “intermediate” CD14++CD16+, and “nonclassical” CD14+CD16++ monocytes (Ziegler-Heitbrock et al., 2010). These three subsets are shown to differ significantly in phenotype, function, and inflammatory and activation potential. The classical CD14++CD16− monocytes (about 90% of total monocytes seen in blood) specialize in phagocytosis, production of reactive oxygen species, and secretion of inflammatory cytokines in response to ligands for extracellular Toll-like receptors (such as the bacterial product LPS) (Saha and Geissmann, 2011). Compared to classical monocytes, the intermediate subset (about 5% of monocytes) displays the characteristics of activated cells. Such cells ha ve a high expression of MHC class II (HLA-DR) antigen and elevated intracytoplasmic levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF (Hristov and Weber, 2011). In contrast, nonclassical monocytes (about 5% of monocytes) do not generate ROS and are weak phagocytes taking-up preferentially oxidised LDL but secrete substantial levels of inflammatory cytokines (TNF and interleukin [IL]-1β) after Toll-like receptor-dependent activation by LPS (Belge et al., 2002) or by viruses and nucleic acids (Cros et al., 2010). Thus, nonclassical monocytes might serve as patrolling immune cells that readily remove virally infected or injured cells and detoxify oxidised LDL (Auffray et al., 2007).

Among patients with chronic inflammation or aging individuals, the percentage of classical monocytes decreases, and subsets of monocytes that express CD16 antigen are expanded (Merino et al., 2011; Ziegler-Heitbrock, 2007). Especially, CD16-expressing nonclassical and intermediate monocytes increase during atherosclerosis and may play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases (Heine et al., 2012) as an important source of TNF and other proinflammatory cytokines (Belge et al., 2002; Hristov and Weber, 2011; Ziegler-Heitbrock, 2007). Furthermore, these subsets express increased levels of vascular adhesion molecules, display a high capacity for adhesion to endothelial cells (Dimitrov et al., 2010) and mobilize preferentially into the circulation during physical stress such as exercise (Hong and Mills, 2008; Steppich et al., 2000). However, little is known about their migratory responses in relation to proinflammatory cytokine production in response to acute stressors, in particular among individuals with elevated BP. Thus, we investigated monocytic TNF production based on the subpopulation (nonclassical, intermediate, or classical monocytes) and their trafficking pattern during physical stress (i.e., a moderate exercise challenge) in participants with elevated BP or normal BP (NBP) in this study.

An acute bout of exercise results in immediate activation of the sympathetic nervous system and markedly increases levels of catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine) in circulating blood, as repeatedly shown in previous studies (Hong and Mills, 2008). Catecholamines mobilize CD16-expressing monocytes from marginal pool in recirculation, in particular, (Steppich et al., 2000) and have a suppressive effect on monocytic TNF production (Dimitrov et al., under review). Examining monocytic proinflammatory cytokine production in response to acute exercise in individuals with elevated BP helps to understand monocytes’ inflammatory potential under the SNS and cardiovascular activation in conjunction with their trafficking pattern. Abnormalities in sympathoadrenergic system are regarded as a key factor in the development and progression of arterial hypertension and may result in adrenergic receptor (AR) desensitization (Grassi et al., 2010). Hence, we also determined AR sensitivity by treating monocytes with isoproterenol (Iso) and assessing the degree of inhibition in LPS-stimulated TNF production. We hypothesize a reduction in the exercise-induced mobilization of nonclassical and intermediate monocytes for subjects with high BP. We also expect a reduction in the exercise-induced inhibition of TNF production in monocyte sub-populations for subjects with high BP, which may be explained by desensitization of ARs expressed on monocytes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

All subjects gave informed consent to the protocol, which was approved by the University of California, San Diego Institutional Review Board. Seventy-seven otherwise healthy men and women with normal or elevated BP were recruited from the local community for a larger study of the role of obesity on vascular inflammation and immune cell activation in PHT. To confirmeligibility, all subjects underwent blood tests for liver, metabolic, lipid, and thyroid panels were obtained, and a normal resting electrocardiogram (ECG) was confirmed before the protocol began. Individuals who had a history of heart disease, liver or renal disease, diabetes, psychosis, severe asthma, pregnancy, or ongoing inflammatory diseases (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, lupus) were excluded. Participants were categorized as “normotensive” (Systolic BP (SBP) ≤120 and/or Diastolic BP (DBP) ≤80 mmHg), “mild prehypertensive” (SBP between 121 and 130 and/or DBP between 81 and 85 mmHg), or “high prehypertensive” (SBP between 131 and 139 and/or DBP between 86 and 89 mmHg) (Chobanian et al., 2003). BP was measured using a Dinamap Compact BP® monitor (Critikon, Tempa, FL) and defined as the average of six seated BP measures taken over two separate days.

2.2. Exercise tests

Participant’s maximal exercise capacity was determined by measuring peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak) by having participants exercise on a treadmill (TMX 425C; Trackmaster Fitness, Eastlake, OH) until maximal exertion (voluntary cessation). The standard Bruce protocol was used where the speed and grade of the treadmill increased gradually by 1.7 mph and 10 % every 3 min. Subject’s expired gas was analyzed using Sensormedics metabolic cart (Sensormedics, Yorba Linda, CA) equipped with Vmax software (Version 6-2A), and the ECG was monitored using Marquette CardioSoft V.3 (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). Participants returned between 9:00 am and 9:30 am 7-14 days later to exercise on the treadmill for 20 min at 65 - 70 % of their VO2peak, normally rated as “somewhat hard” on Borg’s perceived exertion scale. Blood was collected before and immediately after the 20-min exercise challenge through an i.v. catheter inserted into an antecubital vein using minimal tourniquet. Participants refrained from consumingnicotine, caffeine, or alcohol, and from vigorous exercise 24-h prior to the exercise test.

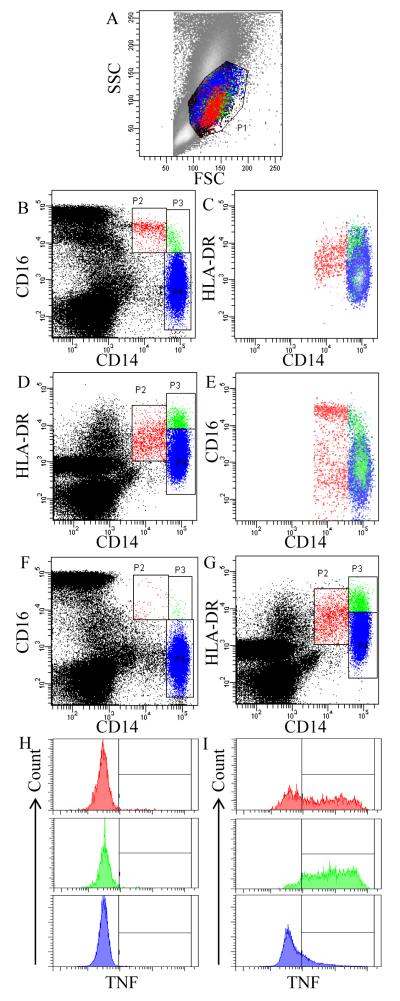

2.3. Surface phenotypic marker expression

The cellular analysis methods for monocyte subsets and TNF expression are depicted in Figure 1. First, monocytes were identified by placing the monocyte gate using a forward and side scatter plot (Fig. 1A). The values of monocyte subsets were expressed as percentages (%) of total monocytes. In determining monocyte subsets, the expression levels of CD16 and HLA-DR among CD14+ cells were used for cells that were unstimulated (Fig. 1A – E) and LPS-stimulated (for TNF expression; Fig. 1F – I), respectively. The use of HLA-DR in place of CD16 for LPS-stimulated monocytes was based on that CD16, but not HLA-DR, is substantially down-regulated upon LPS stimulation. Firstly, and as previously done (Hong and Mills, 2008; Steppich et al., 2000), differential expression levels of CD14 and CD16 was used to distinguish three subpopulations: nonclassical CD14+CD16++, intermediate CD14++CD16+, and classical CD14++CD16− monocytes (Fig. 1B). Alternatively, these three monocyte subpopulations can be differentiated based on the expression levels of CD14 and HLA-DR (Fig. 1D), which approximate nonclassical, intermediate, and classical monocytes. Figures 1 C and E show that distinguishing the monocyte subpopulations based on the CD16 and HLA-DR expression levels is comparable to each other; intermediate monocytes express the highest levels of HLA-DR (HLA-DR++), followed by nonclassical (HLA-DR+), and classical monocytes (HLA-DR+/−).

Fig. 1.

Gating strategy for identifying monocyte subpopulations and analyzing TNF expression from a representative subject with normal blood pressure: in the absence (A - E) or presence (F - I) of LPS. (A) A gate P1 is drawn around putative monocyte populations based on their forward and side scatter (FSC and SSC) characteristics. (B) Differential expression of CD14 and CD16 distinguishes nonclassical CD14+CD16++ (P2), intermediate CD14++CD16+ (P3), and classical CD14++CD16− (P4) monocytes. (C) HLA-DR expression by nonclassical, intermediate, and classical monocytes. (D) Differential expression of CD14 and HLA-DR can also distinguish three monocyte subpopulations: CD14+HLA-DR+ monocytes (P2), CD14++HLA-DR++ (P3), and CD14++HLA-DR+/− (P4). (E) CD16 expression by CD14+HLA-DR+, CD14++HLA-DR++, and CD14++HLA-DR+/− monocytes. (F) LPS-stimulated monocytes down regulate their CD16 expression, but retain the expression of (G) CD14 and HLA-DR. Differential TNF production by CD14+HLA-DR+, CD14++HLA-DR++, and CD14++HLA-DR+/− (top to bottom) in the (H) absence (as a negative control) or (I) presence of anti-TNF antibody.

2.4. Intracellular TNF production and detection

Pre- and post-exercise whole blood was analyzed for LPS-stimulated monocytic TNF production. In addition, to determine the sensitivity of β-ARs to β-agonists, the suppression of monocytic TNF production by Iso (1 × 10−8 M, 1 × 10−9 M and 1 × 10−10 M) in pre-exercise cells was analyzed.

The dose of 200 pg/mL LPS (E. coli 0111:B4, catalog # L4391, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) that is found previously in chronic infections (Kiechl et al., 2001; Wiedermann et al., 1999) and was determined to be appropriate for significant activation of monocytes in preliminary experiments, with 30 to 90 % of cells producing TNF. Peripheral blood cells were incubated in sterile polypropylene plates with or without LPS for 3.5 hours at 37°C with 5 % CO2. To stop cytokine excretion, (allowing intracellular detection), brefeldin A (10 μg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) was added during the last 3 hours of incubation.

Intracellular TNF production of monocytes was evaluated by multiparametric flow cytometry using fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies. Briefly, erythrocytes were lysed using ammonium chloride solution followed by centrifugation (5 min at 500 × g). The cell pellet was washed one time with PBS, containing 0.1 % azide and 0.5 % bovine serum albumin, prior to incubation with monoclonal antibodies (15 min) for monocyte subpopulation identification: HLA-DR/PE (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), CD16/PerCP and CD14/APC (Biolegend, San Diego, CA). After fixation and permeabilization according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit, BD Biosciences), cells were stained intracellularly with TNF/FITC antibody (Biolegend). At least 10,000 gated monocytes were collected for each sample on a dual-laser FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). Because LPS led to significant downregulation of CD16 expression, HLA-DR was used in addition to CD14 to distinguish between nonclassical, intermediate, and classical monocytes (Fig. 1F-G). The percentage of the CD14+HLA-DR+, CD14++HLA-DR++ and CD14++HLA-DR+/− monocytes that were positive for TNF (“% TNF+ monocytes”) from CD14+HLA-DR+, CD14++HLA-DR++ or CD14++HLA-DR+/−, respectively and the median fluorescent intensity (MFI) of TNF, representing the average expression levels, were assessed.

2.5. TNF levels in plasma

Blood for plasma TNF was drawn in EDTA vacutainers before and after the exercise and placed on ice. After centrifugation in a refrigerated centrifuge, plasma was stored at −80°C until the assays were done. Plasma levels of TNF was measured using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD). The intraassay variation was 4.5%.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Three stages of statistical analyses were performed (SPSS Statistical Software 19.0). First, 2 exercise [time: pre and post]-by-3 monocyte subsets or 4 Iso (concentrations: 0, 10−10, 10−9, and 10−8M]-by-3 monocyte subsets repeated measures ANOVA were performed to examine monocyte subset differences in their response to exercise or ex vivo Iso incubation, respectively, in all subjects. Second, in order to examine the responses of each monocyte subset (in terms of TNF expression or % change) to exercise or ex vivo Iso incubation in individuals based on the BP status, interactions were analysed using two-way, 2 exercise [pre and post]-by-3 group [high PHT, mild PHT and NT] or 4 Iso (concentration: 0, 10−10, 10−9, and 10−8M]-by-3 group [high PHT, mild PHT and NT] repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) for each monocyte subset separately. BMI and gender that were previously observed and hypothesized to be different based on BP (Okosun et al., 2004; Tsai et al., 2005) were used as covariates in order to control for the possible effects of them on monocyte responses to exercise. The significance of pre- to post-exercise changes in % monocytes subsets and TNF expression for each BP group was further examined by paired t-test. Skewed data distribution was determined by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and variables not normally distributed were log-transformed. Differences of the gender and race among the BP groups were examined using Pearson’s Chi-squared tests. F and p values are presented based on linear or quadratic function as appropriate. In addition, Pearson correlation analyses were performed to identify relationship between SBP or DBP and, respectively, changes in exercise-induced mobilization and exercise-induced TNF inhibition of monocyte subsets. If normal distribution could not be assumed, Spearman rank correlations were calculated. Data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined at an alpha level of .05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics and metabolic responses during exercise

The demographic characteristics of 75 subjects are presented in Table 1 according to the BP groups. BMI, gender, and resting BP were significantly different between the three groups. High prehypertensive individuals were heaviest and, by definition, showed significantly higher systolic and diastolic BP at rest compared to that of the mild PHT or NT individuals. In addition, gender distribution across the BP groups indicated an equal distribution of men and women in the high prehypertensive group, a higher percentage of men in the mild prehypertensive group, and a higher percentage of women in the normotensive group. There were no differences in the mean age, race, or heart rate at rest. The overall ethnic composition was as follows: 51% Caucasian American, 22% African American, 16% Asian American, 7% Hispanic American, and 4% other.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and metabolic measurements during peak exercise of the study participants with normal and elevated BP.

| Variable | High prehypertensive (N=21) |

Mild prehypertensive (N=28) |

Normotensive (N=26) |

F/χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic BPa (mmHg) at rest | 135.6 ± 0.9 | 124.5 ± 0.9 | 107.1 ± 1.7 | 119.2*** |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) at rest | 81.7 ± 1.8 | 77.3 ± 1.1 | 68.7 ± 1.2 | 23.6*** |

| Heart rate (beats/min) at rest | 72.1 ± 3.1 | 69.2 ± 1.8 | 69.7 ± 2.1 | 0.15 |

| Age (years) | 41.9 ± 2.0 | 40.9 ± 2.2 | 41.7 ± 2.0 | 0.07 |

| Gender (male/female)b | 11/10 | 19/9 | 9/17 | 6.0* |

| Race (White/others)b | 14/7 | 15/13 | 14/12 | 4.4 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 33.3 ± 1.2 | 30.0 ± 0.9 | 26.3 ± 1.3 | 9.5*** |

| VO2peakc (ml/kg/min) | 30.4 ± 2.2 | 34.7 ± 2.1 | 31.8 ± 2.1 | 1.1 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) during exercise | 162.4 ± 5.8 | 154.9 ± 4.2 | 132.2 ± 3.9 | 12.7*** |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) during exercise | 84.5 ± 2.7 | 79.0 ± 2.7 | 71.2 ± 2.3 | 7.2** |

| Heart rate (beats/min) during exercise | 128.7 ± 4.3 | 138.7 ± 4.3 | 133.3 ± 4.0 | 1.1 |

Values are presented as mean ± SEM

indicate p < .05

indicate p < .01

indicate p < .001, respectively

BP, blood pressure

Denotes non-parametric χ2 test

VO2peak, peak oxygen consumption

Cardiovascular fitness adjusted for body mass (VO2peak in ml/kg/min) did not differ between the three BP groups, indicating that the relative difficulty of the exercise challenge was similar for the groups regardless of their BP or fitness levels, as intended (30.4 ± 2.2, 34.7 ± 2.1 and 31.8 ± 2.1, p > .05; for high prehypertensive, mild prehypertensive, and normotensive groups, respectively). During the 20-min moderate exercise, prehypertensive individuals exhibited significantly higher SBP and DBP than normotensive (Table 1).

3.2. Defining monocyte subpopulations using CD16 vs. HLA-DR

When blood monocytes were stimulated with LPS for TNF expression, CD16 molecules were substantially down-regulated such that the subpopulations could not be identified based on the CD16 expression pattern (Fig. 1F). Unlike CD16, the monocytic expression of HLA-DR was intact upon LPS stimulation (Fig. 1G compared to Fig. 1D, unstimulated). Thus, HLA-DR and CD14 were examined to distinguish between nonclassical, intermediate, and classical monocytes as compared to discerning those using CD16 also in unstimulated cells. The majority of CD14+HLA-DR+ nonclassical monocytes expressed CD16, about half of CD14++HLA-DR++ monocytes were intermediate, and CD14++HLA-DR+/− were identical to classical monocytes (Fig. 1E). Table 2 presents the average % of three monocyte subsets based on CD16 and HLA-DR expression levels among all 75 subjects. Cellular patterns depicting monocyte subets from a representative subject with normal BP are shown in Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Average (N=75) % of nonclassical, intermediate, and classical subpopulation of total monocytes defined based on either CD14 and CD16, or CD14 and HLA-DR expression.

| Monocyte subpopulation | Phenotype | % of total monocytes |

Phenotype | % of total monocytes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonclassical | CD14+CD16++ | 4.2 ± 0.3 | CD14+HLA-DR+ | 7.1 ± 0.4 |

| Intermediate | CD14++CD16+ | 4.8 ± 0.3 | CD14++HLA-DR++ | 5.1 ± 0.2 |

| Classical | CD14++CD16− | 87.8 ± 0.6 | CD14++HLA-DR+/− | 85.9 ± 0.5 |

Values are presented as mean ± SEM

3.3. LPS-stimulated TNF expression of monocyte subpopulations

We, then, analyzed LPS-stimulated TNF production in the three monocyte subpopulations based on the HLA-DR expression (Fig. 1G). A typical example of TNF production, from a representative subject with normal BP is shown in Fig. 1 H and I (in the absence or presence of anti-TNF antibody, respectively). In all subjects, the average MFI of TNF expression was 319 ± 20.0 in CD14+HLA-DR+ monocytes, 541 ± 36.9 in CD14++HLA-DR++ monocytes, while CD14++HLA-DR+/− monocytes expressed TNF with an MFI of 54.6 ± 4.8 (p < .001); the TNF expression levels in CD14++HLA-DR+/− monocytes were 6-fold lower than those in CD14+HLA-DR+ monocytes and 10-fold lower than those in CD14++HLA-DR++ monocytes.

Monocyte subpopulations also differed in the % monocytes producing TNF (% TNF+ monocytes). The average % expressing TNF+ was 79.7 ± 1.1 % among CD14+HLA-DR+, 92.1 ± 0.9 % among CD14++HLA-DR++, and 44.8 ± 2.2 among CD14++HLA-DR+/− monocytes (p < .001) in all subjects (N= 75).

3.4. Differences in monocyte subset mobilization responses to a moderate exercise challenge irrespective of blood pressure groups

First, we analyzed the effect of moderate treadmill exercise on circulating monocyte subsets when they are distinguished based on the surface expression of CD14 and CD16 (no LPS). Exercise-by-monocyte subset interaction was significant for % monocyte change (F (2,148) = 35.4, p < .001), indicating different responses to exercise among the three subsets of monocytes: the % nonclassical monocytes of total monocytes increased (4.2 to 5.0 %, pre- to post-exercise), the % intermediate monocytes did not change (4.8 to 5.0 %, pre- to post-exercise), whereas the % classical monocytes decreased (87.9 to 86.7 %, pre- to post-exercise).

In order to confirm the validity of using the HLA-DR expression pattern for LPS-stimulated samples, we also compared the trafficking pattern of monocyte subsets using CD14 and HLA-DR expression to that of using only CD16. Exercise-by-monocyte subset interaction was again significant for the % monocyte change (F (2,148) = 11.8, p < .001), indicating different responses to exercise among the three subsets of monocytes: the % CD14+HLA-DR+ monocytes (of total monocytes) increased (7.1 to 8.1 %, pre- to post-exercise), the % CD14++HLA-DR++ monocytes did not change (5.1 to 4.8 %, pre- to post-exercise), whereas the % CD14++HLA-DR+/− monocytes decreased (86.0 to 84.7 %, pre- to post-exercise).

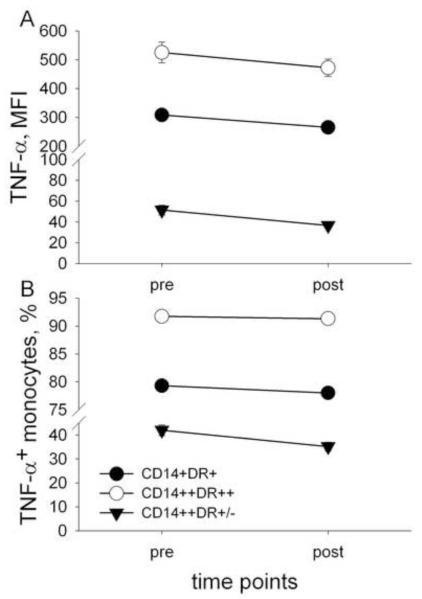

3.4. TNF expression in monocyte subsets in response to exercise irrespective of blood pressure groups

Next, we examined the effect of exercise on LPS-stimulated TNF production by the three subsets of monocytes distinguished based on CD14 and HLA-DR expression. Exercise-by-monocyte subset interaction was significant for MFI of TNF expression (F (2,148) = 18.3, p < .001), indicating different TNF expression levels pre- to post-exercise among the three subsets of monocytes: MFI of TNF of all subsets decreased post-exercise, however this decrease was the largest in CD14 ++HLA-DR+/− (17.6 ± 1.1 %), followed by that of CD14+HLA-DR+ (by 7.5 ± 0.8 %), and CD14++HLA-DR++ monocytes (by 1.7 ± 0.3 %, Fig. 2A) being the smallest.

Fig. 2.

Median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of TNF expression and % TNF+ monocyte subsets after stimulation of blood cells with LPS before and after exercise. The MFI (A) and % TNF+ (B) of all three monocyte subsets (CD14+HLA-DR+, CD14++HLA-DR++, CD14++HLA-DR+/−) decreased with the highest MFI and % TNF+ decrease for CD14++HLA-DR+/− monocytes. (Exercise-by-monocyte subset interaction was significant for both MFI of TNF (p < .05) and % TNF+ monocytes (p < .001).

The exercise-by-subset interaction was also significant for the % TNF+ monocytes (F (2,148) = 43.0, p < .001), and the % TNF+ monocyte of all subsets decreased after exercise. Percentage decrease in the % TNF+ monocytes pre- to post-exercise was the largest, again, for CD14++HLA-DR+/− monocytes (13.9 ± 1.1 %), followed by that of CD14+HLA-DR+ monocytes (by 1.4 ± 0.4 %), and finally by CD14++HLA-DR++ monocytes (by 0.3 ± 0.04 %, Fig. 2B).

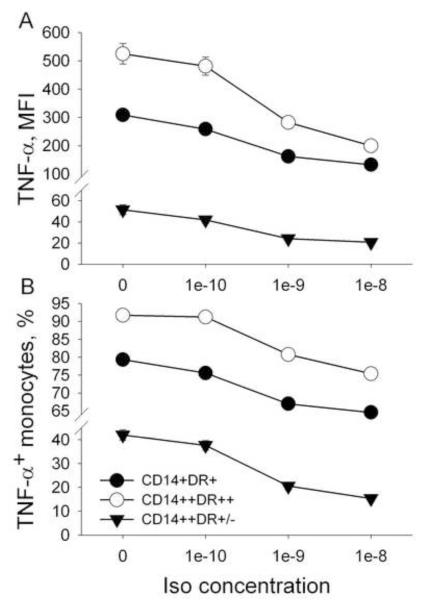

3.5. AR sensitivity: TNF expression in monocyte subsets in response to Iso challenge irrespective of BP groups

Firstly, inhibition of LPS-stimulated monocytic production of TNF by Iso occurred in a dose dependent manner (10−10 to10−8 M). Iso-by-monocyte subset interaction was significant for MFI of TNF (F (6,444) = 4.7, p < .001), indicating different responses to Iso among the three subsets of monocytes. Secondly, this inhibition was most pronounced when Iso was used in a concentration of 10−8 M and the decrease was the largest in CD14++HLA-DR++ monocytes (by 61 ± 6.1%), followed by that of CD14+HLA-DR+ monocytes (by 57 ± 7.1%), and finally by CD14++HLA-DR+/− monocytes (49 ± 5.1%, Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

AR sensitivity of monocyte subsets: Inhibition of MFI of TNF expression and % TNF+ monocyte subsets by increasing concentrations of Isoproterenol (Iso). The MFI and % TNF+ of all three monocyte subsets (CD14+ HLA-DR+, CD14++HLA-DR++, CD14++HLA-DR+/−) decreased with the highest MFI decrease for CD14++HLA-DR++ monocytes and with the highest % TNF+ decrease for CD14++HLA-DR+/ monocytes. (Iso-by-monocyte subset interaction was significant for both MFI of TNF expression (p < .001) and % TNF+ monocytes (p < .001).

The Iso-by-monocyte subset interaction was also significant for the % TNF+ monocytes (F (6,444) = 367, p < .001). This inhibition, again, was most pronounced when Iso was used in a concentration of 10−8 M; however, the decrease was the largest in CD14++HLA-DR+/− monocytes (by 66 ± 4.1%), followed by that of CD14+HLA-DR+ monocytes (by 19 ± 1.1%), and finally by CD14++HLA-DR++ monocytes (18 ± 1.1%, Fig. 3B).

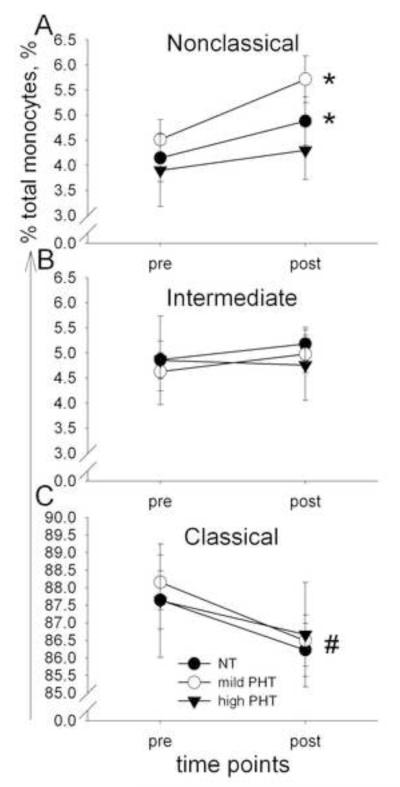

3.6. Effects of BP: Mobilization and LPS-stimulated TNF production of monocyte subsets in response to exercise, and incubation with Iso in participants with high PHT, mild PHT or NBP

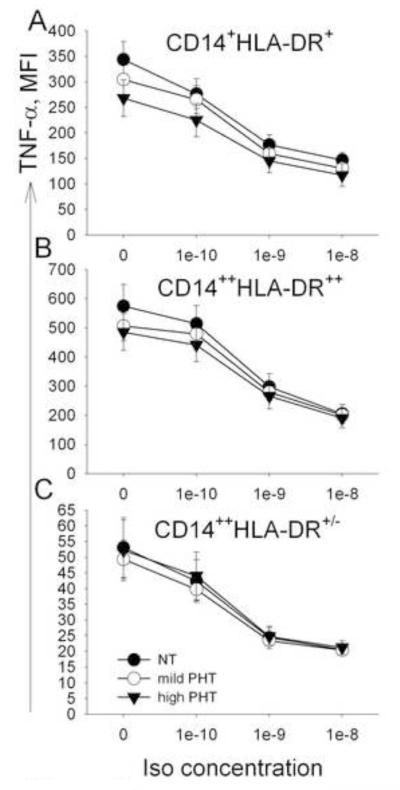

When monocyte subsets were distinguished based on CD14 and CD16 expression, BP significantly affected monocyte trafficking, such that nonclassical monocytes increased in NT and mild PHT, but not in high PHT individuals (p < .05, Fig. 4). Changes in the mobilization of intermediate and classical monocyte subsets did not differ between the three BP groups. When CD14 and HLA-DR markers were used to differentiate monocyte subsets, BP significantly affected only CD14++HLA-DR++ monocytes, such that they decreased in high PHT, but did not change in NT and mild PHT individuals. Trafficking of the other two subpopulation, namely CD14+HLA-DR+, and CD14++HLA-DR+/− monocytes, did not differ between the three BP groups. Inhibition of the LPS-stimulated monocytic TNF production by exercise or incubation with Iso in monocyte subsets was not different between the three BP groups (Fig. 5, for Iso findings).

Fig. 4.

Percentage changes of monocyte subsets before and after exercise in normotensive (NT) vsmild prehypertensive (PHT) vs. high PHT individuals. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of % nonclassical CD14+CD16++ (A), intermediate CD14++CD16+ (B), and classical CD14++CD16+ (C) monocytes. Nonclassical monocytes increased, intermediate did not change, whereas classical decreased. BP significantly affected monocyte trafficking such that nonclassical monocytes increased in NT and mild PHT, but not in high PHT individuals (*p < .05, for statistical differences between pre- and post-exercise values in NT and mild PHT groups (A); #p < .05, for statistical differences between pre- and post-exercise values in all individuals regardless of the BP groups (C)).

Fig. 5.

AR sensitivity by BP groups: Inhibition of MFI of monocytic TNF expression by increasing concentrations of isoproterenol (Iso) in normotensive (NT) vs. mild prehypertensive (mild PHT) vs. high PHT individuals. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of MFI of TNF expression in CD14+HLA-DR+ (A), CD14++HLA-DR++ (B), and CD14++HLA-DR+/− (C) monocytes. There is no Iso-by-BP interaction effect.

3.7. Association between BP and exercise-induced mobilization and inhibition of monocytic TNF production

We examined the nature of the associations between BP levels and the changes in monocytes measures, using Pearson correlation between the SBP or DBP and changes in exercise-induced mobilization and exercise-induced TNF inhibition of monocyte subsets. There was a small negative correlation between SBP and pre- to post-exercise change in mobilization of nonclassical monocytes (r = −0.15, p = 0.1). No other monocyte parameters were significantly correlated with SBP or DBP.

3.8. Spontaneous TNF production by monocytes without LPS and plasma TNF levels

The absence of LPS stimulation resulted only in minimal production of TNF by monocytes, 0.50 ± 0.05 % TNF+ monocytes. Exercise led to a significant decrease in the % TNF+ monocytes to 0.40 ± 0.05 % post-exercise (p < 0.001), regardless of BP groups. Plasma TNF levels also did not differ between BP groups and did not change pre- to post-exercise (7.1 ± 0.4 pg/ml to 7.4 ± 0.4 pg/ml).

4. Discussion

The differential mobilization of monocyte subsets in response to a physical stressor under sympathoadrenergic activation has been reported in the literature, but inflammatory cytokine production by those subsets and their trafficking responses in hypertension are largely unknown. In this study we show that TNF production in all monocyte subsets decreased post-exercise, irrespective of BP, with nonclassical and intermediate monocytes being a major source of LPS-stimulated TNF production. In addition, we show that the % increase in nonclassical monocytes (previously shown as “inflammatory”) was blunted in individuals with elevated BP (high PHT) during a moderate exercise bout in spite of little effects of mild BP elevation on TNF production by monocyte subsets. We also confirmed previously reported findings (Hong and Mills, 2008; Steppich et al., 2000) of preferential mobilization of CD16 expressing monocytes into peripheral blood during a moderate exercise bout in a larger independent sample in this study. We show that among CD16-expressing monocytes, the % CD16++ monocytes (i.e. nonclassical) increased whereas % CD16+ (i.e. intermediate) did not change, implying that nonclassical monocytes that express high levels of CD16 have the greatest capability to mobilize into peripheral blood under sympathoadrenal activation.

We found only a trend toward lower LPS-stimulated TNF production by monocytes in individuals with PHT in comparison to those with NBP. This difference disappeared after controlling for BMI, implying the potential role of adiposity in regulation of stimulated TNF production by monocytes among individuals with mildly elevated BP. It remains to be determined if stimulated TNF production is further impaired among individuals with more established hypertension.

Monocytes were initially defined on the basis of morphology and later by flow cytometry into two distinct monocyte subpopulations: the classical CD16− monocytes and the minor CD14+CD16+/++ subset (Passlick et al., 1989). However, for more recent nomenclature for monocytes, studies highlighted the merit of subdividing the CD16 monocytes into the intermediate (CD14++CD16+) and nonclassical (CD14+CD16++) subsets (Ziegler-Heitbrock et al., 2010). As our results showed, a distinguishing feature of nonclassical and, in particular, intermediate monocytes was the high levels of TNF production in response to LPS stimulation. This finding is consistent with previous studies in which TNF was detected using intracellular staining in whole blood after activation with Toll-like receptor ligands (Belge et al., 2002; Wong et al., 2011). Another characteristic of these two subsets was their high expression of HLA-DR. Taken together, these monocyte subsets appear to have high inflammatory potential and antigen presenting features, implying their primary role in vascular inflammatory diseases.

Our findings of inhibition of LPS-stimulated TNF production by both Iso in-vitro and an exercise challenge in-vivo indicate that sympathoadrenal activation during moderate exercise has a suppressive effect on monocytic TNF production mediated via β2-ARs. Furthermore, our results show that adrenergic agonist-induced inhibition of TNF production was the highest for the intermediate monocytes, suggesting the greatest β2-AR sensitivity to agonists in these monocytes. Whereas, inhibition of TNF production pre- to post-exercise was the greatest in classical monocytes, implying that other mechanisms (such as mobilization of cells with differing β2-AR expression levels to peripheral blood) might play an additional role in differing TNF production by monocyte subsets under adrenergic activation.

We found a blunted mobilization response of nonclassical monocytes during exercise in high PHT individuals. This may be indicative of monocytic AR desensitization and/or greater adhesion of nonclassical monocytes to the vascular endothelium in individuals with elevated BP. Previously, greater increases in adhesion of immune cells to HUVECs were also reported in hypertensive patients post exercise (Mills et al., 2000). Unlike the mobilization response, the degrees of inhibition of TNF production by Iso did not differ between the BP groups, suggesting that our group of healthy individuals with relatively mild BP elevation (compared to clinical hypertension) exhibited little difference in AR sensitivity from normotensive individuals for monocytic TNF production. These findings imply an association between elevated adhesion molecule expression on monocytes and high BP. However, the nature of this association and its clinical implications for vascular pathology by inflammatory monocyte infiltration remain to be further elucidated. Furthermore, the role of sympathoadrenal system in vascular inflammation and hypertension warrants additional investigation.

A growing body of evidence suggests that intermediate monocytes, in particular, contribute to the development of atherosclerosis in the general population as well as in patients with chronic kidney diseases (Heine et al., 2012; Zawada et al., 2011), whereas nonclassical monocytes might be involved in the innate local surveillance of tissues and the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases (Cros et al., 2010). Hence, there may be preferential expansion, activation, and/or migration of the intermediate and nonclassical monocyte subsets under different disease conditions. Our results provide the evidence that sympathoadrenal activation during physical stress preferentially mobilize nonclassical monocytes.

What is the basis for the selectivity of the stress-induced mobilization in nonclassical monocytes? Among all monocyte subtypes nonclassical monocytes express the highest levels of lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) and fractalkine receptor (CX3CR1) (Wong et al., 2011). We believe that this unique profile of adhesion molecule LFA-1 and chemokine receptor CX3CR1 makes nonclassical monocytes residents of the marginal pool, and that changes of these molecules via stimulation of β2-ARs induce their demargination (Chigaev et al., 2008). Strengthening this view, it has previously been shown that nonclassical monocytes patrol the endothelium of blood vessels, in an LFA-1 and CX3CR1-dependent manner (Cros et al., 2010). Moreover, high density of LFA-1 and CX3CR1 is strongly correlated with adrenergic leukocytosis in vivo (Dimitrov et al., 2010).

We show that the mobilization of nonclassical “proinflammatory” monocytes under sympathoadrenal activation is attenuated with even mild BP elevation. The clinical implications of these differential monocyte migration patterns in individuals with elevated BP remain to be further clarified. We found only a trend toward lower LPS-stimulated TNF production by monocytes in individuals with PHT. Future studies in individuals with more established hypertension will likely further clarify the effect of clinically elevated BP on TNF production under acute stress and sympathoadrenal activation and the role of AR sensitivity of inflammatory immune cells.

Research highlight.

This work shows that the mobilization of CD16+ proinflammatory monocytes under physical stress is attenuated in individuals with prehypertension.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the research grants R01HL090975 and HL090975S1 (American Recovery and Reinvestment Act grant) to SH and UL1RR031980 for the UCSD Clinical and Translational Science Awards from the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Reference List

- Auffray C, Fogg D, Garfa M, Elain G, Join-Lambert O, Kayal S, Sarnacki S, Cumano A, Lauvau G, Geissmann F. Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science. 2007;317:666–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1142883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belge KU, Dayyani F, Horelt A, Siedlar M, Frankenberger M, Frankenberger B, Espevik T, Ziegler-Heitbrock L. The proinflammatory CD14+CD16+DR++ monocytes are a major source of TNF. J. Immunol. 2002;168:3536–3542. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branen L, Hovgaard L, Nitulescu M, Bengtsson E, Nilsson J, Jovinge S. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:2137–2142. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000143933.20616.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chigaev A, Waller A, Amit O, Sklar LA. Galphas-coupled receptor signaling actively down-regulates alpha4beta1-integrin affinity: a possible mechanism for cell de-adhesion. BMC. Immunol. 2008;9:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr., Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr., Roccella EJ. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cros J, Cagnard N, Woollard K, Patey N, Zhang SY, Senechal B, Puel A, Biswas SK, Moshous D, Picard C, Jais JP, D’Cruz D, Casanova JL, Trouillet C, Geissmann F. Human CD14dim monocytes patrol and sense nucleic acids and viruses via TLR7 and TLR8 receptors. Immunity. 2010;33:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov S, Lange T, Born J. Selective mobilization of cytotoxic leukocytes by epinephrine. J. Immunol. 2010;184:503–511. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi G, Seravalle G, Quarti-Trevano F. The ‘neuroadrenergic hypothesis’ in hypertension: current evidence. Exp. Physiol. 2010;95:581–586. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.047381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine GH, Ortiz A, Massy ZA, Lindholm B, Wiecek A, Martinez-Castelao A, Covic A, Goldsmith D, Suleymanlar G, London GM, Parati G, Sicari R, Zoccali C, Fliser D. Monocyte subpopulations and cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Mills PJ. Effects of an exercise challenge on mobilization and surface marker expression of monocyte subsets in individuals with normal vs. elevated blood pressure. Brain Behav. Immun. 2008;22:590–599. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hristov M, Weber C. Differential role of monocyte subsets in atherosclerosis. Thromb. Haemost. 2011;106:757–762. doi: 10.1160/TH11-07-0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll MA, Platt AM, Potteaux S, Randolph GJ. Monocyte trafficking in acute and chronic inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:470–477. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khder Y, Briancon S, Petermann R, Quilliot D, Stoltz JF, Drouin P, Zannad F. Shear stress abnormalities contribute to endothelial dysfunction in hypertension but not in type II diabetes. J. Hypertens. 1998;16:1619–1625. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816110-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiechl S, Egger G, Mayr M, Wiedermann CJ, Bonora E, Oberhollenzer F, Muggeo M, Xu Q, Wick G, Poewe W, Willeit J. Chronic infections and the risk of carotid atherosclerosis: prospective results from a large population study. Circulation. 2001;103:1064–1070. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.8.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Larson MG, Leip EP, Beiser A, D’Agostino RB, Kannel WB, Murabito JM, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Lifetime risk for developing congestive heart failure: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2002;106:3068–3072. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039105.49749.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinou K, Tousoulis D, Antonopoulos AS, Stefanadi E, Stefanadis C. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: from pathophysiology to risk stratification. Int. J. Cardiol. 2010;138:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.03.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKellar GE, McCarey DW, Sattar N, McInnes IB. Role for TNF in atherosclerosis? Lessons from autoimmune disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2009;6:410–417. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino A, Buendia P, Martin-Malo A, Aljama P, Ramirez R, Carracedo J. Senescent CD14+CD16+ monocytes exhibit proinflammatory and proatherosclerotic activity. J. Immunol. 2011;186:1809–1815. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills PJ, Maisel AS, Ziegler MG, Dimsdale JE, Carter S, Kennedy B, Woods VL., Jr. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell-endothelial adhesion in human hypertension following exercise. J. Hypertens. 2000;18:1801–1806. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018120-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okosun IS, Boltri JM, Anochie LK, Chandra KM. Racial/ethnic differences in prehypertension in American adults: population and relative attributable risks of abdominal obesity. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2004;18:849–855. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passlick B, Flieger D, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Identification and characterization of a novel monocyte subpopulation in human peripheral blood. Blood. 1989;74:2527–2534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha P, Geissmann F. Toward a functional characterization of blood monocytes. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2011;89:2–4. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoog T, Dichtl W, Boquist S, Skoglund-Andersson C, Karpe F, Tang R, Bond MG, de FU, Nilsson J, Eriksson P, Hamsten A. Plasma tumour necrosis factor-alpha and early carotid atherosclerosis in healthy middle-aged men. Eur. Heart J. 2002;23:376–383. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steppich B, Dayyani F, Gruber R, Lorenz R, Mack M, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Selective mobilization of CD14(+)CD16(+) monocytes by exercise. Am. J. Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C578–C586. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.3.C578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai PS, Ke TL, Huang CJ, Tsai JC, Chen PL, Wang SY, Shyu YK. Prevalence and determinants of prehypertension status in the Taiwanese general population. J. Hypertens. 2005;23:1355–1360. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000173517.68234.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedermann CJ, Kiechl S, Dunzendorfer S, Schratzberger P, Egger G, Oberhollenzer F, Willeit J. Association of endotoxemia with carotid atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease: prospective results from the Bruneck Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1999;34:1975–1981. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KL, Tai JJ, Wong WC, Han H, Sem X, Yeap WH, Kourilsky P, Wong SC. Gene expression profiling reveals the defining features of the classical, intermediate, and nonclassical human monocyte subsets. Blood. 2011;118:e16–e31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-326355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawada AM, Rogacev KS, Rotter B, Winter P, Marell RR, Fliser D, Heine GH. SuperSAGE evidence for CD14++CD16+ monocytes as a third monocyte subset. Blood. 2011;118:e50–e61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-326827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler-Heitbrock L. The CD14+ CD16+ blood monocytes: their role in infection and inflammation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2007;81:584–592. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0806510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, Dalod M, Grau V, Hart DN, Leenen PJ, Liu YJ, MacPherson G, Randolph GJ, Scherberich J, Schmitz J, Shortman K, Sozzani S, Strobl H, Zembala M, Austyn JM, Lutz MB. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood. 2010;116:e74–e80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-258558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]