Abstract

Protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR1) is an unusual G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) that is activated through proteolytic cleavage by extracellular serine proteases. While previous work has shown that inhibiting PAR1 activation is neuroprotective in models of ischemia, traumatic injury, and neurotoxicity, surprisingly little is known about PAR1’s contribution to normal brain function. Here we used PAR1 −/− mice to investigate the contribution of PAR1 function to memory formation and synaptic function. We demonstrate that PAR1 −/− mice have deficits in hippocampus-dependent memory. We also show that while PAR1 −/− mice have normal baseline synaptic transmission at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses, they exhibit severe deficits in N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR)-dependent long-term potentiation (LTP). Mounting evidence indicates that activation of PAR1 leads to potentiation of NMDAR-mediated responses in CA1 pyramidal cells. Taken together, this evidence and our data suggest an important role for PAR1 function in NMDAR-dependent processes subserving memory formation and synaptic plasticity.

Keywords: Protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR1), hippocampus, astrocyte, learning, memory, long-term potentiation (LTP)

Introduction

Protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR1) is a member of a unique family of four GPCRs (PAR1-4) that are activated by proteolytic cleavage of their extracellular amino terminus by serine proteases such as thrombin and plasmin. This cleavage reveals a new amino terminus that acts as a tethered ligand to activate the receptor. Upon activation, PAR1 can couple to Gαq/11, Gαi/o, Gα12/13, and their respective intracellular signaling pathways (Coughlin, 2000; Macfarlane et al., 2001, Ramachandran and Hollenberg, 2008). In the CNS, PAR1 activation has a multitude of effects, ranging from nerve growth factor (NGF) secretion, neurite retraction, and astrocyte proliferation (Noorbakhsh et al., 2003). In mammalian brains, PAR1 is highly expressed in specific neuronal populations in the cortex, the basal ganglia, the striatum, and the nucleus accumbens (Weinstein et al., 1995; Niclou et al., 1998; Striggow et al., 2001). PAR1 is also highly expressed in the amygdala and the hippocampus, areas that are important for learning and memory. Within the hippocampus, PAR1 is expressed predominantly in astrocytes in area CA1 (Weinstein et al., 1995; Striggow et al., 2001; Junge et al., 2004), and has recently been shown to be expressed in dentate granule cells (Han et al., 2011).

PAR1 has been extensively studied for its roles in neuronal damage after ischemic or traumatic injury (Striggow et al., 2001; Guo et al., 2004; Hamill et al., 2005). In models of ischemia and hypoxia, PAR1 ablation or pharmacological inhibition results in reduced infarct volume (Junge et al., 2003; Olson et al., 2004). In a cortical stab wound model, PAR1 activation triggers astrogliosis associated with glial scar formation after traumatic brain injury (Nicole et al., 2005). PAR1 blockade or removal can also protect dopaminergic nerve terminals in the striatum in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease (Hamill et al., 2007).

A few studies have begun to provide some insight into PAR1’s role in normal brain function. In a mouse model of nicotine addiction, activation of PAR1 in dopaminergic neurons regulates nicotine-induced dopamine release and conditioned place preference (Nagai et al., 2006). PAR1 activation can also modulate synaptic responses in the hippocampus. Activation of PAR1 in astrocytes leads to the release of glutamate, which can be sensed by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) in neurons, and can thus potentiate NMDAR function (Gingrich et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2007; Mannaioni et al., 2008; Shigetomi et al., 2008). Furthermore, this enhanced NMDAR response can facilitate the induction of long-term potentiation (LTP; Maggio et al., 2008). Together, these data suggest the possibility that PAR1 activity may influence memory formation and synaptic plasticity.

Here for the first time, we directly tested the hypothesis that PAR1 function is a regulator of NMDAR-dependent memory formation and synaptic function in the hippocampus. Using PAR1 −/− mice (Connolly et al., 1996), we found that loss of PAR1 function results in deficits in hippocampus-dependent memory formation, as well as pronounced loss of NMDAR-dependent long-term potentiation. We propose that PAR1 is a novel regulator of synaptic responses and a modulator of astrocyte-neuron interactions underlying memory formation.

Materials and Methods

Animals

PAR1 −/− and wild-type (WT) mice were obtained by crossing PAR1+/- mice, a gift from Dr. Shaun Coughlin (University of California, San Francisco, CA), with C57BL/6 wild-type mice from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). A colony of homozygous PAR1−/− and WT mice that were >99% C57Bl/6 (>7 back-crossings) were derived from heterozygous breeding pairs. Mice were housed up to five per cage and maintained by the UAB Animal Resources Program. Food and water were available ad libitum. The colony room was maintained on a 12 hour light–dark cycle. All experiments were performed with University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Animal Care and with national regulations and policies.

Cresyl Violet Staining

Mice were deeply anesthetized with an i.p. injection of 100 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital and then transcardially perfused with physiological (0.9%) saline, followed by formalin (10 % v/v of 37% formaldehyde, buffered with sodium phosphate, Fisher Scientific). Whole brains were extracted and post-fixed overnight at 4 °C in formalin + 30% w/v sucrose. Tissue was coronally sectioned at 40μm. Sections were then rehydrated and stained with 0.5% cresyl violet.

Contextual Fear Conditioning

For contextual fear conditioning, adult (>8 weeks old) littermate WT and knockout mice were placed in the training chamber, and after a two minute exploration period, they received a mild foot-shock (0.75 mA, 1 s). This was repeated for a total of three shocks, with two minutes between each shock. After the final shock, the animal remained in the chamber for one minute and was then returned to its home cage (Miller et al., 2007). Fear learning was assessed 24 hours later by recording freezing behavior during a seven minute re-exposure to the fear conditioning chamber. Freezing during the training period was also measured as an index of initial responsiveness and learning.

Electrophysiology

Hippocampi from adult WT and knockout mice were rapidly removed and 400μm-thick transverse slices were prepared on a vibratome (Leica VT1000S) while immersed in an ice-cold cutting solution containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 0.5 CaCl2, 7 MgCl2, 10 D-glucose; pH was adjusted to 7.4, osmolarity to 300 mOsm, and saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2. Slices were maintained for at least 1 hour in an incubation chamber at room temperature in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 D-glucose; pH was adjusted to 7.4, osmolarity to 300 mOsm, and saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2.

Extracellular field recordings were performed at 32 °C in a submersion chamber on an upright microscope (Zeiss Axioskop 2 FS+), and slices were superfused with oxygenated ACSF. Borosilicate glass recording electrodes (A-M systems; 1–3 MΩ resistance) filled with ACSF were placed in stratum radiatum of area CA1, and stimuli were delivered via a nickel dichromate bipolar electrode positioned along the Schaffer collateral afferents from area CA3. Recordings were made with either a MultiClamp 700B or an Axopatch 200B amplifier and digitized with a Digidata 1440A (Axon Instruments). Data were acquired, stored and analyzed using pClamp 10.2 (Axon Instruments) and OriginPro 7 (OriginLab Corp).

For LTP experiments, stimulus intensity was set to 40–50% of the threshold for observing population spikes at the stratum radiatum recording electrode. A minimum of 30 min of baseline stimulation (0.05 Hz) was recorded before LTP induction. LTP was induced by a theta-burst protocol composed of a train of 10 stimulus bursts delivered at 5 Hz, with each burst consisting of four pulses at 100 Hz (Bahr et al., 1997; Kramar et al., 2004). For LTP threshold and saturation experiments, a single burst (four pulses at 100 Hz) was delivered every 15 minutes until no further potentiation was observed.

Electrophysiological data are presented as mean ± SEM, and 10–90% rise slopes of the downward-deflecting field excitatory postsynaptic potential waveform (i.e., fEPSP slopes) were measured. For theta-burst stimulation responses, the areas of the composite responses produced by each theta burst within the train were measured. Areas of bursts 2–10 were then divided by the area of the initial theta burst to produce a relative area (Bahr et al., 1997; Kramar et al., 2004).

Protein extraction and Western Blotting

Tissue homogenization was performed as described by Tongiorgi et al. (2003). Briefly, tissue was homogenized in 1 mL/100 mg homogenization buffer (25 mM Tris HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton-X) with Complete Protease inhibitors (Roche) and PhosSTOP (Roche). After vortexing, samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 minutes. A DC Protein Concentration Assay (Thermo-Scientific) was performed on the supernatant, and the final concentration was adjusted to 2 μg/μL with homogenization buffer.

Samples were incubated at 70 °C for 10 minutes with 5x Lane Marker Sample Buffer (Thermo Scientific) containing 5% BME. 20 μg of protein was run on 8% polyacrylamide gels and transferred overnight to Immobilon-FL PVDF (Millipore). Blots were blocked in Odyssey Blocking Buffer (Li-Cor) and TBS for 1 hour at RT. Blots were incubated for 1h at RT in primary antibodies in TBST, washed in TBST, and incubated for 1h at RT in secondary antibody in 1:2 Odyssey Blocking Buffer and TBST. Primary antibodies were used against the ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits: GluA1 (1 μg/mL, Abcam ab31232), GluA2/3 (1:100, Millipore AB1506), GluN1 (1:1000, Sigma G 8913), GluN2A (1:2000, Millipore AB1555), GluN2B (1:500, Millipore AB1557P) and Beta III Tubulin as a loading control (1:1000, Millipore AB15708). Secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit IRDye 800 (1:15,000, Li-Cor). For stripping, blots were shaken for 10–15 min twice in 25 mM glycine, pH 2.0, containing 1% SDS, and then washed in TBST. Imaging was done to verify efficacy of stripping.

Odyssey Infrared Imaging (LiCor) was used to image all Western blots. Odyssey 2.1 software was used to perform quantification of image intensity. Integrated intensity was calculated for all bands. Values were normalized to tubulin loading control levels, and protein levels in PAR1−/− samples were calculated relative to PAR+/+ controls.

mRNA Isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

Hippocampus and cortex were isolated, immediately frozen and stored at −80 °C. RNA was extracted with AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini kit (Qiagen). Tissue was disrupted and homogenized with mortar and pestle for approximately 90 seconds, and RNA was eluted in 35 μl RNAse-free water and stored at −20 °C. A total of 1.5 μg RNA was used to synthesize cDNA with oligo (dT)18 primers according to protocol (RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit, Fermentas). Samples were diluted to 80 μl with water and amplified with quantitative RT-PCR reactions consisting of 2 μl cDNA, 300 nM each of forward and reverse primer and 2x iQ SYBR Green Supermix in a total sample volume of 20 μl (Bio-Rad). Primers amplifying PAR-1 are as follows: 5′-ACATGTACGCCTCCATCATGCTCA-3′ (Forward) and 5′-CACCCAAATGACCACGCAAGTGAA-3′ (Reverse). Control HPRT primers sequences were: 5′-GGAGTCCTGTTGATGTTGCCAGTA-3′ (Forward) and 5′-GGGACGCAGCAACTGACATTTCTA-3′ (Reverse). PCR reactions were performed with iQ5 real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad) and the following protocol: 95 °C for 3:00, 35 cycles of 95 °C for 0:15 and 59.4 °C for 1:00, and 95°C for 1:00. A melt curve from 55 °C to 95°C was included to verify uniqueness of the amplicon. PCR products were diluted with 6x Gel Loading Dye (NEB), and 8 μl were subjected to electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel with 1 μg/ml ethidium bromide. Gels were analyzed with a UV imager (Bio-Rad).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using two-sample Student’s t-test for comparison of means. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant (* = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01, *** = p<0.001). All errors are expressed as SEM.

Results

PAR1 −/− mice show hippocampus-dependent learning and memory deficits

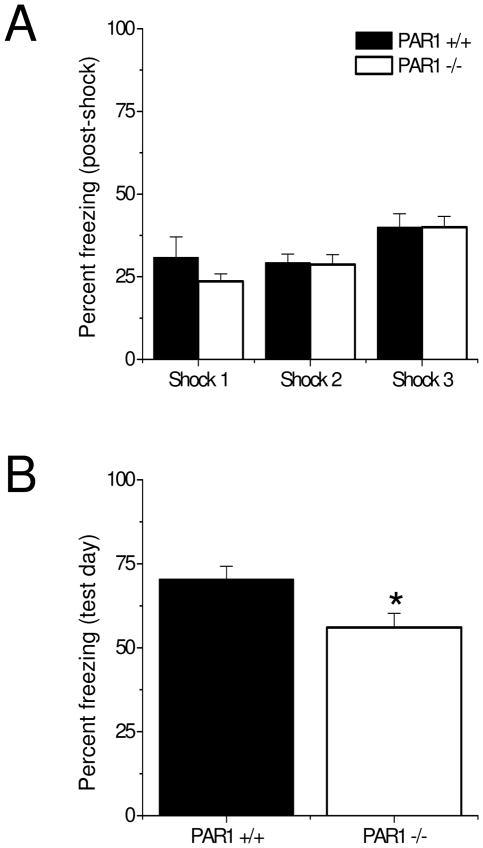

We have previously demonstrated that PAR1 −/− mice have significant impairments in passive avoidance and cued fear conditioning tests when compared to age-matched but non-littermate controls (Almonte et al., 2007). These associative learning paradigms were chosen because they are robust, single-trial tests with reliably measurable behavioral responses correlated with learned behavior (i.e., escape latencies in passive avoidance, and freezing behavior in fear conditioning). Although the amygdala certainly plays a critical role in memory formation in passive avoidance and in fear conditioning (Walker and Davis, 2002; Sweatt, 2010), these paradigms have become useful tests of hippocampus-dependent learning (Whitlock et al., 2006; Sweatt, 2010). We therefore sought to explore further this phenotype by testing WT and littermate PAR1 −/− mice in contextual fear conditioning, a fear conditioning paradigm distinct from the one we used in our prior study.

We first confirmed our previous observation that there were no differences in total distance traveled between littermate WT and PAR1 −/− mice in an open field (data not shown). Next, we tested WT and PAR1 −/− mice in the contextual fear conditioning test, in which animals learn to fear the environment in which they were trained. During the training session, animals are placed in a novel context, allowed to explore for a short time, and then receive a foot shock. During the testing session, the animals are returned to the same context, and freezing behavior is measured (Sweatt, 2010). As shown in Fig. 1A, PAR1 −/− mice showed similar levels of post-shock freezing behavior as littermate WT mice during training. This is consistent with our prior observation that PAR1 −/− mice do not exhibit deficits in foot-shock sensitivity (Almonte et al., 2007). On the test day, however, PAR1 −/− mice displayed significantly less freezing in response to the context than littermate WT mice (Fig. 1B, n=9 mice per genotype, PAR1 +/+: 70.48 ± 3.77, PAR1 −/−: 56.05 ± 4.23). These results suggest that, just as in cued fear conditioning, PAR1 function in the amygdala could regulate the formation of the novel context-foot shock association in the contextual fear conditioning paradigm. Moreover, the deficit in contextual fear conditioning we observed in the present studies supports the idea of a hippocampus-dependent memory deficit in PAR1 −/− mice.

Figure 1. PAR1 −/− mice show significant impairments in contextual fear conditioning.

(A) PAR1 −/− mice show similar freezing behavior after each foot-shock as wild-type mice during training. (B) PAR1 −/− mice show significantly less freezing behavior on the test day (n=9 mice per genotype, PAR1 +/+: 70.48 ± 3.77, PAR1 −/−: 56.05 ± 4.23). Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Taken together, the impairments observed in the PAR1 −/− mice in the passive avoidance, cued fear conditioning (Almonte et al., 2007), and contextual fear conditioning paradigms suggest that intact PAR1 function in the amygdala at a minimum, and likely also in the hippocampus, is necessary for memory formation in multiple forms of associative learning.

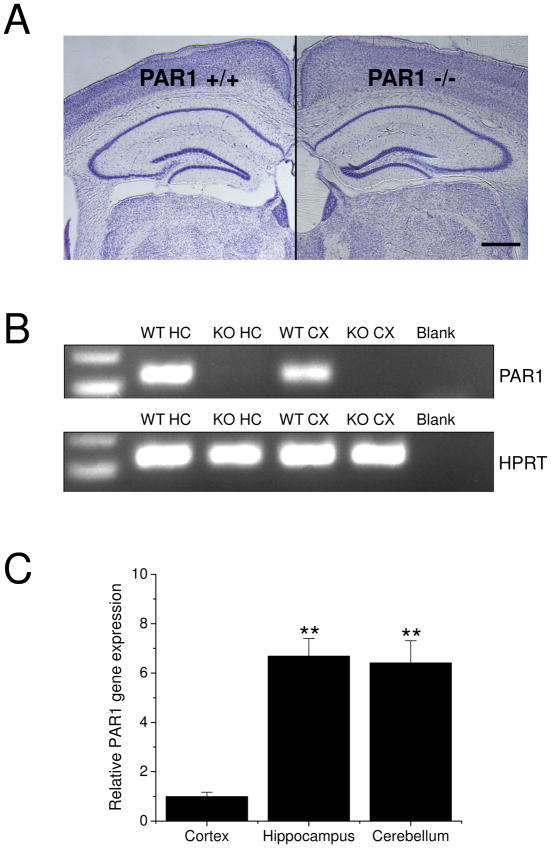

PAR1 −/− mice have normal hippocampal morphology

In order to ascertain if the PAR1 −/− mice exhibited defects in gross hippocampal and CNS anatomy, we prepared WT and PAR1 −/− brains for morphological assessment. Cresyl violet staining showed that PAR1 −/− mice have normal hippocampal morphology (Fig. 2A) and no detectable levels of PAR1 mRNA in hippocampal and cortical tissue (Fig 2B). In WT mouse brains, PAR1 gene expression was especially highly enriched in hippocampus and cerebellum, relative to cortex (Fig. 2C; n=3 brains from WT mice; cortex: 1 ± 0.173, hippocampus: 6.91 ± 0.714, cerebellum: 6.63 ± 0.895).

Figure 2. Loss of PAR1 function does not alter hippocampal morphology.

(A) There are no gross abnormalities in hippocampal morphology as visualized by cresyl violet staining between PAR1+/+ and PAR1 −/− mice. Scale bar: 0.5 mm. (B) PAR1 mRNA expression is present in tissue from PAR1 +/+ (WT) hippocampus (HC) and cortex (CX). There are no detectable levels of PAR1 mRNA in either hippocampal or cortical tissue from PAR1 −/− (KO) mice. (C) In WT mice, PAR1 gene expression is highly enriched in cortex, hippocampus and cerebellum (n=3 brains from WT mice; cortex: 1 ± 0.173, hippocampus: 6.91 ± 0.714, cerebellum: 6.63 ± 0.895). Data are normalized to cortex and presented as mean ± SEM.

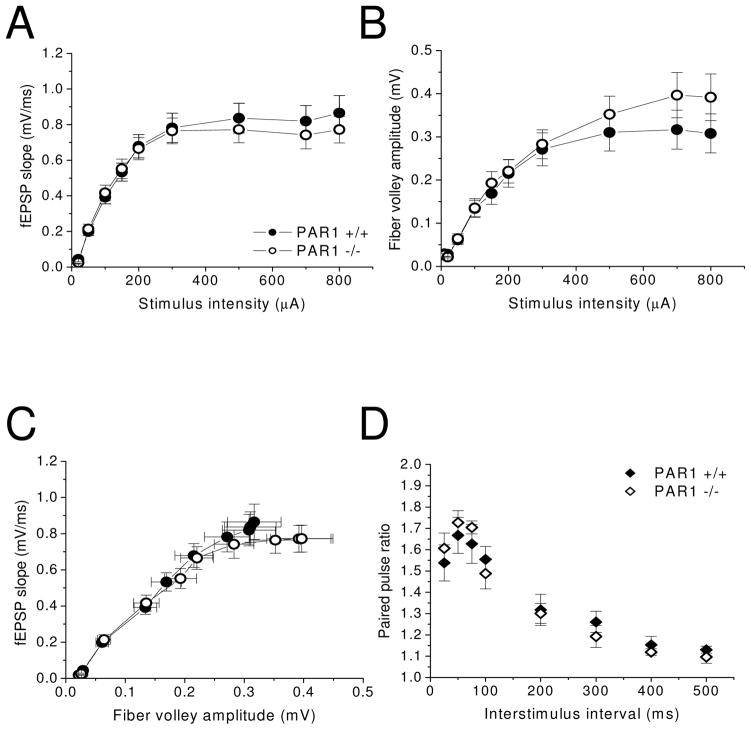

PAR1 −/− mice have normal baseline transmission and short-term plasticity at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses

Given the significance of hippocampal involvement in passive avoidance and contextual fear conditioning, we next investigated the role of PAR1 function at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses. We therefore assessed baseline synaptic transmission and short-term plasticity using extracellular field recording in vitro. The field excitatory postsynaptic potential (fEPSP) magnitudes in response to increasing levels of stimulus intensities were recorded and plotted as input-output curves. These experiments revealed no significant differences in synaptic responses as measured by the rise slope of the fEPSP waveform, (i.e., fEPSP slope) at the tested stimulus intensities between PAR1 −/− mice and WT mice (Fig 3A; PAR1 +/+: n=25 slices from 8 mice; PAR1 −/−: n=25 slices from 7 mice). Additionally, fiber volley amplitudes, which reflect the number of presynaptic axons that are activated to give rise to a synaptic response, were not significantly different between PAR1 −/− and WT mice (Fig. 3B). Plotting fEPSP slope versus fiber volley amplitude, further emphasizes that there are no significant differences in stimulus responses between PAR1 −/− and WT mice (Fig. 3C). Overall, these results indicate that loss of PAR1 function does not adversely affect the number of presynaptic axons that need to be stimulated to elicit a synaptic response at a given stimulus intensity, nor does loss of PAR1 function adversely affect basic postsynaptic mechanisms of excitatory synaptic transmission.

Figure 3. PAR1 −/− mice have normal baseline synaptic transmission and paired-pulse facilitation at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses.

PAR1 −/− mice display comparable baseline synaptic transmission as wild-type mice, as measured by (A–C) input-output curves (PAR1 +/+: n=25 slices from 8 mice; PAR1 −/−: n=25 slices from 7 mice). (D) PAR1 −/− mice also display normal short-term plasticity at these synapses as measured by paired-pulse facilitation (PAR1 +/+: n=11 slices from 4 mice; PAR1 −/−: n=9 slices from 4 mice). Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Short-term plasticity refers to changes in synaptic strength that occur over time scales of milliseconds to minutes, and is generally thought to occur through presynaptic changes in neurotransmitter release (Zucker and Regehr, 2002). Short-term plasticity can be observed by measuring responses to stimulation with pairs of pulses given at various interstimulus intervals. Short-term facilitation occurs when the response to the second pulse is greater than the first pulse, and short-term depression occurs when the response to the second pulse is smaller than the first pulse. Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses typically show short-term facilitation (Dobrunz and Stevens, 1997). The results of our paired-pulse experiments show no significant differences in paired-pulse facilitation between PAR1 −/− mice and WT (Fig. 3D; PAR1 +/+: n=11 slices from 4 mice; PAR1 −/−: n=9 slices from 4 mice). These results indicate that PAR1 does not play a role in basic presynaptic mechanisms of neurotransmitter release.

Taken together, the input-output curves and paired-pulse facilitation measurements indicate that loss of PAR1 function is not detrimental to baseline synaptic transmission or short-term plasticity at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses. Moreover, cresyl violet staining of hippocampal slices from both PAR1 −/− and WT mice show that loss of PAR1 does not alter hippocampal morphology (Fig. 2A). These observations imply that PAR1 does not participate in cellular processes regulating neurotransmitter release at presynaptic terminals or postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptor responses during baseline synaptic transmission. These data further suggest that the memory formation deficits observed in the PAR1 −/− mice in the behavior tests are not due to changes in hippocampal morphology, baseline synaptic responses, or impaired neurotransmitter release.

PAR1 −/− mice have impaired long-term potentiation

LTP at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses requires the activation of NMDA receptors (NMDARs), an influx of Ca2+, activation of intracellular signaling pathways, and gene transcription following transient stimulation (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993; Nicoll and Malenka, 1999; Sweatt, 2001; Sweatt, 2004; Day and Sweatt, 2010). Multiple lines of evidence suggest that activation of PAR1 in hippocampal slices potentiates NMDAR-mediated responses and facilitates the induction of LTP via this mechanism (Gingrich et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2007; Mannaioni et al., 2008; Maggio et al., 2008; Shigetomi et al., 2008). These observations, along with the normal baseline synaptic transmission results discussed above, suggest that PAR1 may modulate activity-dependent processes, such as LTP. We therefore tested the idea that the behavioral phenotype of the PAR1 −/− mice could be explained by impaired LTP.

Theta-burst stimulation (TBS) was chosen as the LTP induction protocol for several reasons. First, because TBS mimics the bursts of activity observed in hippocampal electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings in awake animals during certain learning tasks, it is considered a physiologically-relevant stimulus protocol (Larson and Lynch, 1986; Larson et al., 1986; Larson and Lynch, 1988; Diamond et al., 1988; Bliss and Collingridge, 1993). Second, TBS results in robust, NMDAR-dependent LTP at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses (Larson and Lynch, 1988; Diamond et al., 1988; Muller and Lynch, 1988). Finally, mechanisms underlying TBS-induced LTP at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses have been extensively studied (Larson and Lynch, 1986; Larson et al., 1986; Larson and Lynch, 1988; Muller and Lynch, 1988; Arai and Lynch, 1992; Arai et al., 1994; Arai et al., 2004; Kramar et al., 2004), thereby providing well-characterized parameters for evaluating the effects of the loss of PAR1 function on LTP.

Our LTP studies demonstrate that TBS elicited robust levels of LTP in WT slices, while PAR1 −/− slices displayed a striking, progressive diminution of potentiation throughout the 120 min recording period (Fig. 4A; PAR1 +/+: n=8 slices from 5 mice; PAR1−/−: n=7 slices from 4 mice, #=PAR1 −/− vs. 1.0, p<0.001). Further, Fig. 4B shows that while post-tetanic potentiation (PTP) magnitudes did not differ between genotypes (PAR1 +/+: 2.13 ± 0.07, PAR1 −/−: 1.96 ± 0.04), LTP magnitudes in slices from PAR1 −/− mice were consistently significantly lower than in slices from WT mice at 20 minutes (Fig. 4B; PAR1 +/+: 1.56 ± 0.05, PAR1 −/−: 1.41 ± 0.01), 60 minutes (PAR1 +/+: 1.56 ± 0.03, PAR1 −/−: 1.17 ± 0.02), and 120 minutes post-TBS (PAR1 +/+: 1.56 ± 0.01, PAR1 −/−: 1.17 ± 0.01). Because PTP is another form of short-term plasticity mediated by presynaptic mechanisms (Zucker and Regehr, 2002), the lack of observed differences in PTP magnitudes between genotypes is consistent with the paired-pulse facilitation observations described above (Fig. 3D), and further suggests that PAR1 is not likely involved in presynaptic processes during burst activity. These observations therefore point towards a postsynaptic locus for PAR1 activity.

Figure 4. Loss of PAR1 function results in impaired synaptic plasticity at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses.

(A) PAR1 −/− mice display significantly decreased levels of LTP after induction by theta-burst stimulation (TBS; PAR1 +/+: n=8 slices from 5 mice; PAR1−/−: n=7 slices from 4 mice; #=PAR1 −/− vs. 1.0, p<0.001). LTP magnitudes, measured by averaging normalized fEPSP slopes for the last 10 minutes of recording were: PAR1 +/+: 1.56 ± 0.01, and PAR1 −/−: 1.17 ± 0.01. Insets show representative traces before and after LTP induction. Scale bars: 0.2 mV, 20 ms. (B) PAR1 −/− mice show comparable levels of PTP, but also show significantly less potentiation at 20, 60, and 120 minutes post-TBS. (C, D) PAR1 −/− mice have impaired synaptic responses during TBS. The areas of the composite responses produced by each theta burst within the train were measured. Areas of Bursts 2–10 were then divided by the area of the initial theta burst to produce a relative area. (C) Representative traces for bursts 1, 4, and 10. PAR1 +/+: black traces, PAR1 −/−: gray traces. Scale bars: 0.5 mV, 15 ms. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (E) fEPSP areas and decay times of synaptic responses at 50% of the threshold for eliciting population spikes were not significantly different between wild-type and PAR1 −/− mice (PAR1 +/+: n=27 slices from 9 mice, PAR1 −/−: n=27 slices from 8 mice). Insets show representative traces from each genotype (PAR1 +/+: black trace, PAR1 −/−: gray trace). Scale bars: 0.5 mV, 20 ms.

The lower LTP magnitudes measured in the PAR1 −/− slices indicate a necessity for PAR1 in the induction of LTP at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses. Assuming a postsynaptic locus, PAR1 seems to affect synaptic processes that are engaged during burst activity but not during baseline synaptic transmission. A few possibilities that could explain how loss of PAR1 could result in lower LTP magnitudes include impaired synaptic responses during delivery of the LTP induction protocol, a change in the threshold for LTP, and a change in the number of ionotropic glumate receptors (iGluRs; i.e., AMPARs or NMDARs). To begin to address these possibilities, in the next series of experiments we assessed synaptic responses during the period of theta-burst stimulation. This allowed us to determine if acute synaptic responses (and associated short-term plasticity) were perturbed in the PAR1 −/− synapses.

PAR1 −/− mice have impaired responses to theta-burst stimulation

The effects of loss of PAR1 function during TBS were assessed by measuring the areas of the composite responses produced by each burst within the train. In analyzing these data, areas under the EPSP curve of bursts 2–10 were normalized to the area of the initial theta burst to produce a relative area. This analysis normalizes differences between slices in the area of the initial burst response, thus allowing for the detection of differences that arise during the stimulus train (Bahr et al., 1997; Kramar et al., 2004). As the representative traces in Fig. 4C illustrate, theta-burst response waveforms from PAR1 −/− slices were markedly different than those from WT slices. The summarized data in Fig. 4D further show that theta-burst responses in PAR1 −/− slices were significantly depressed during the train, rather than facilitated, as in the WT slices. The pattern of facilitation during the theta-burst train observed in the WT slices is consistent with descriptions from previous reports (Bahr et al., 1997; Kramar et al., 2004). These results indicate that PAR1 regulates the acute facilitation of synaptic responses that occurs during LTP induction by TBS, an important insight into a potential locus for PAR1 function at excitatory synapses.

For baseline stimulation and delivery of the TBS protocol in these LTP experiments, a stimulation intensity that was 40–50% of the threshold for eliciting population spikes was used. To confirm that this stimulation intensity elicited similar synaptic responses in both WT and PAR1 −/− slices, the area and decay kinetics of the fEPSP waveform were analyzed. As Fig. 4E illustrates, there were no significant differences in the areas under the curve (AUC) of the fEPSP (PAR1 +/+: 5.15 ± 0.79, n=27 slices from 9 mice; PAR1 −/−: 6.42 ± 0.88, n=27 slices from 8 mice) or decay times (PAR1 +/+: 11.7 ± 0.77, PAR1 −/−: ± 12.44 ± 0.78). These data are consistent with the input-output curves (Fig. 3A–C) demonstrating that loss of PAR1 does not affect baseline synaptic transmission but only affects synaptic responses during burst stimulation. These observations lend further support to the idea that PAR1 function is important for the augmentation of synaptic function that occurs during the induction of hippocampal long-term plasticity.

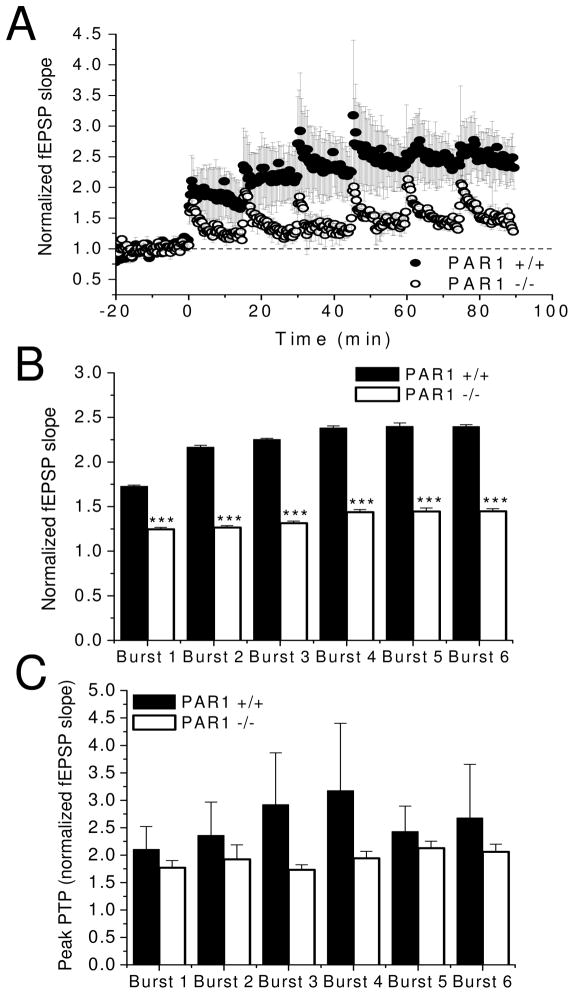

Loss of PAR1 function reduces the ceiling for long-term potentiation

The reduced levels of LTP in PAR1 −/− slices could be due to an increased LTP induction threshold, such that LTP might be recoverable with repeated stimulus trains or with maximally effective levels of stimulation during the TBS. To assess the first possibility, single bursts (4 pulses at 100 Hz) were delivered every 15 minutes until no further potentiation was observed (i.e., potentiation was saturated). As the results from our threshold and saturation experiments demonstrate, both WT and PAR1 −/− slices reached a plateau in potentiation after the fourth burst application (Fig. 5A, B; PAR1 +/+: n=3 slices from 3 mice; PAR1−/−: n=3 slices from 3 mice; p<0.001). Table 1 lists average fEPSP slopes for the last 3 minutes of each burst period. LTP saturation, measured by averaging normalized fEPSP slopes for the last 3 minutes of recording after Bursts 4–6 were: PAR1 +/+: 2.39 ± 0.006, and PAR1−/−: 1.44 ± 0.002. Interestingly, potentiation levels were consistently lower in slices from PAR1 −/− mice, compared to slices from WT mice. As with the PTP measurements from the TBS experiments previously discussed (Fig. 4B), the PTP magnitudes after each burst delivery were not significantly different between genotypes (Fig. 5C, Table 2), further supporting the interpretation that that PAR1 is not likely involved in presynaptic processes during burst activity. Thus, these experiments reveal that the maximal level of LTP (i.e., ceiling) that is achievable is severely diminished in PAR1 −/− slices, as saturated LTP magnitudes were significantly lower than in WT slices despite repeated burst applications. These results support the interpretation that PAR1 mediates the facilitation of synaptic responses to burst stimulation. Moreover, the lowered LTP ceilings in the PAR1 −/− slices indicate that loss of PAR1 attenuates the temporal integration of theta-burst responses during LTP induction.

Figure 5. Loss of PAR1 function reduces the ceiling for LTP.

(A) PAR1 −/− mice have significantly lower saturation levels for LTP (PAR1 +/+: n=3 slices from 3 mice; PAR1 −/−: n=3 slices from 3 mice). (B) PAR1 −/− mice display significantly lower levels of potentiation following each burst. LTP saturation levels were: PAR1 +/+: 2.39 ± 0.006, and PAR1−/−: 1.44 ± 0.002. (C) Peak PTP levels following each burst delivery were not significantly different between wild-type and PAR1 −/− mice.

Table 1.

LTP magnitudes after each delivered burst in threshold and saturation experiments.

| Burst # | PAR1 +/+ avg fEPSP slope | ±SEM | PAR1 −/− avg fEPSP slope | ±SEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.73 | 0.014 | 1.25 | 0.023 |

| 2 | 2.17 | 0.020 | 1.27 | 0.021 |

| 3 | 2.25 | 0.014 | 1.31 | 0.025 |

| 4 | 2.38 | 0.024 | 1.44 | 0.027 |

| 5 | 2.40 | 0.038 | 1.45 | 0.039 |

| 6 | 2.40 | 0.022 | 1.45 | 0.031 |

Table 2.

Peak PTP magnitudes after each delivered burst in threshold and saturation experiments.

| Burst # | PAR1 +/+ avg fEPSP slope | ±SEM | PAR1 −/− avg fEPSP slope | ±SEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.11 | 0.417 | 1.77 | 0.131 |

| 2 | 2.36 | 0.608 | 1.92 | 0.264 |

| 3 | 2.92 | 0.948 | 1.73 | 0.090 |

| 4 | 3.17 | 1.231 | 1.94 | 0.124 |

| 5 | 2.43 | 0.465 | 2.13 | 0.128 |

| 6 | 2.68 | 0.976 | 2.06 | 0.139 |

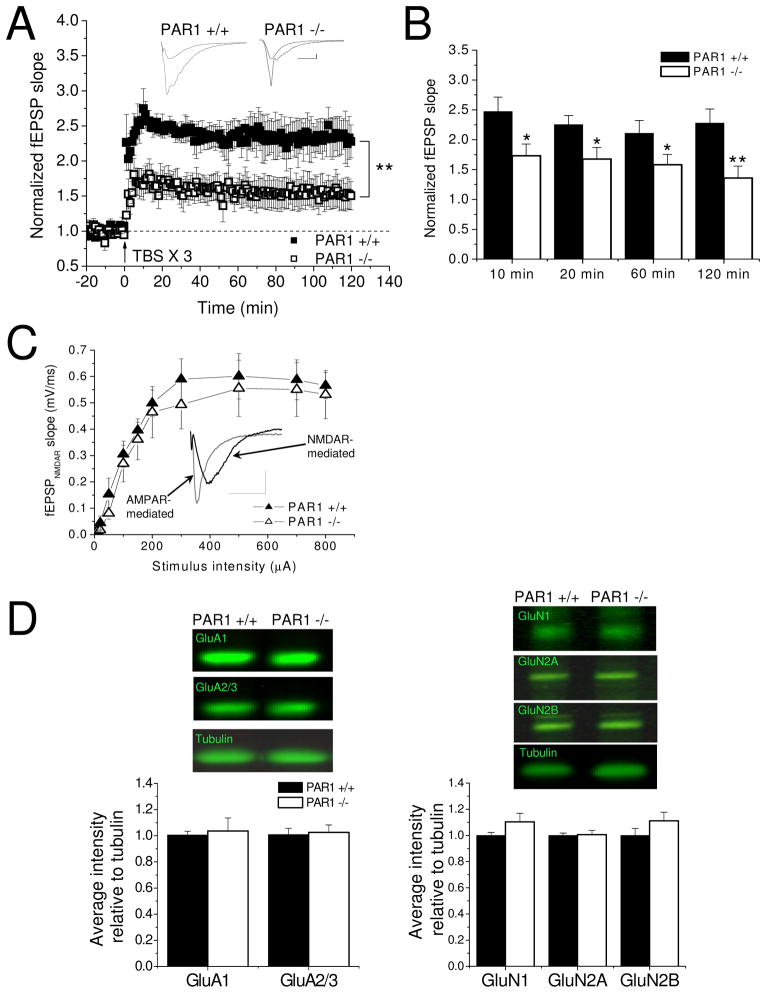

Activation of NMDARs has been previously shown to be critical for induction of TBS-induced LTP (Larson and Lynch, 1986; Larson and Lynch, 1988; Diamond et al., 1988; Muller and Lynch, 1988). Thus, experiments were performed under conditions favoring NMDAR activation to address the possibility that impaired NMDAR function could account for the LTP deficits in the PAR1 −/− mice. In these experiments, 10 μM EDTA was added to the ACSF to relieve Zn2+ inhibition of NMDAR activation (Erreger and Traynelis, 2005; Erreger and Traynelis, 2007), and a robust induction protocol consisting of three TBS trains delivered at 20 second intervals was used (Selcher et al., 2003). Even under conditions of augmented NMDAR function, PAR1-deficient slices still exhibited a large reduction in the level of LTP achievable (Fig. 6A; PAR1 +/+: n=5 slices from 3 mice, PAR1 +/+: n=5 slices from 3 mice, p<0.01). Further, PAR1 −/− slices consistently displayed lower LTP magnitudes at 10 minutes (Fig. 6B; PAR1 +/+: 2.47 ± 0.24; PAR1 −/−: 1.73 ± 0.19), 20 minutes (PAR1 +/+: 2.25 ± 0.15; PAR1 −/−: 1.68 ± 0.19), 60 minutes (PAR1 +/+: 2.11 ± 0.22; PAR1 −/−: 1.58 ± 0.18), and 120 minutes post-TBS (PAR1 +/+: 2.28 ± 0.24; PAR1 −/−: 1.36 ± 0.20). These data further support the idea that PAR1 function is critical in mediating temporal integration of synaptic responses during the induction of and maximum potentiation levels for NMDAR-dependent LTP.

Figure 6. Loss of PAR1 function impairs the induction and ceiling for NMDAR-dependent LTP, but does not impair NMDAR function or expression.

(A) Lower saturation levels in PAR1 −/− mice persist under conditions favoring NMDAR activation (10 μM EDTA added to ACSF, 3 X TBS stimulation; PAR1 +/+: n=5 slices from 3 mice; PAR1 −/−: n=5 slices from 3 mice) Insets show representative traces before and after LTP induction. Scale bars: 0.2 mV, 20 ms. (B) PAR1 −/− mice show significantly less potentiation at 10, 20, 60, and 120 minutes post-TBS. (C) NMDAR-mediated synaptic responses are not impaired in PAR1−/− mice. Inset shows representative AMPAR-mediated response (gray trace) and NMDAR-mediated response (black trace) (PAR1 +/+: n=7 slices from 4 mice; PAR1 −/−: 7 slices from 3 mice). Scale bars: 0.5 mV, 20 ms. (D) AMPAR and NMDAR subunit expression levels are not significantly altered in PAR1 −/− hippocampal whole-cell lysates (n=6 animals per genotype).

To test if the LTP deficits in the PAR1 −/− mice were due to impaired NMDAR-mediated synaptic transmission, input-output curves were recorded in the presence of 0 mM Mg2+, 4 mM Ca2+, and 10 μM CNQX. These recording conditions allow for the isolation of the NMDAR-dependent component of the fEPSP waveform (inset of Fig. 6C). These experiments reveled no significant differences in NMDAR-mediated synaptic responses at various stimulation intensities in PAR1 −/− slices compared to WT slices (Fig. 6C; PAR1 +/+: n=7 slices from 4 mice, PAR1 −/−: n=7 slices from 3 mice). In addition, Western blot analysis showed there were no significant differences in expression levels of AMPAR or NMDAR subunits in hippocampal whole-cell lysates (Fig. 6D, n=6 per genotype). These observations, along with the input-output curves (Fig. 3A–C) and the fEPSP waveform area and decay kinetics (Fig. 6C), indicate that there are no underlying differences in AMPAR and NMDAR expression or function in the PAR1 −/− mice. Moreover, these data suggest that while NMDAR function and expression do not seem to be impaired in PAR1 −/− mice, loss of PAR1 results in severe deficits in the induction and ceiling for NMDAR-dependent LTP. In concert with the memory formation deficits seen in the PAR1 −/− mice in the passive avoidance and fear conditioning tests, these data indicate critical roles for PAR1 function in synaptic responses during burst stimulation subserving long-term memory formation and long-term synaptic plasticity.

Discussion

The most important finding from this study is that PAR1 activity is critical for NMDAR-dependent memory formation and long-term synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. We show that loss of PAR1 function leads to impaired performance in contextual fear conditioning. Extracellular field recordings from hippocampal slices reveal that PAR1 function is critical for the generation of NMDAR-dependent LTP. These results suggest that PAR1 is a novel mediator of activity-dependent processes subserving memory formation and synaptic plasticity.

PAR1 function in hippocampus-dependent memory formation

Previous work has shown that PAR1 activity can regulate the rewarding effects of nicotine and morphine (Nagai et al., 2006; Ito et al., 2007), and that PAR1 −/− mice show deficits in two forms of emotionally motivated learning (Almonte et al., 2007). These studies along with the current findings argue for a critical role for PAR1 in the formation of multiple types of memory. We assessed PAR1 function in contextual fear conditioning and observed significantly less freezing behavior at 24 hours in PAR1 −/− mice. These deficits are not due to impairments in baseline behaviors as PAR1 −/− mice perform comparably to WT mice in various baseline tests including initial responses to foot-shock (Almonte et al., 2007). Multiple lines of evidence indicate that passive avoidance and both cued and contextual fear conditioning all require NMDAR activation (Walker and Davis, 2002; Whitlock et al., 2006). These results suggest that PAR1 function plays a specific role in NMDAR-dependent and hippocampus-dependent memory formation.

PAR1 activity modulates NMDAR-dependent LTP

The activation of NMDARs, Ca2+ influx, activation of intracellular signaling pathways, including the ERK/MAPK cascade, and gene transcription are obligatory events for LTP (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993; Nicoll and Malenka, 1999; Sweatt 2001; Day and Sweatt, 2010). Extracellular field recordings from PAR1 −/− mice demonstrate strikingly decreased TBS-induced LTP, presenting a possible cellular mechanism for the observed behavior phenotype. Further investigation revealed that loss of PAR1 function results in an insurmountable diminution in the maximum level of LTP achievable with repeated TBS. This observation is consistent with previous suggestions that PAR1 activation can affect LTP threshold (Maggio et al., 2008).

Several factors contribute to the effectiveness of TBS in activating NMDARs during LTP induction. First, the synaptic responses to the first burst within the TBS train produces enough neuronal depolarization to relieve the voltage-dependent Mg2+ block of NMDAR activation (Larson and Lynch, 1988; Traynelis et al., 2010). Second, the subsequent bursts within the TBS train lead to the activation of more NMDARs, ultimately resulting in augmented synaptic responses (i.e., synaptic potentiation) (Larson and Lynch, 1988; Muller and Lynch, 1988). Evidence that TBS-induced LTP is NMDAR-dependent come from observations that TBS delivered in the presence of an NMDAR antagonist fail to elicit LTP (Larson and Lynch, 1988; Diamond et al., 1988; Muller and Lynch, 1988; Arai and Lynch, 1992).

The markedly reduced TBS responses observed in the slices from PAR1 −/− mice then, indicate a crucial role for PAR1 in regulating responses to burst stimulation. The loss of PAR1 function would prevent the enhancement of NMDAR-mediated components of the synaptic response that have been observed following PAR1 activation (Gingrich et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2007, Mannaioni et al., 2008; Maggio et al., 2008), resulting in the lack of sufficient summation of neuronal depolarization and impaired augmentation of responses during the later bursts in the train. Alternatively, it has been suggested that constitutive PAR1 activity underlies a tonic activation of extrasynaptic GluN2B-containing NMDARs (Shigetomi et al., 2008); when the Mg2+ block of these receptors is relieved by activation of synaptic NMDARs following PAR1 activation, the resultant response would appear as a potentiation of the NMDAR-mediated component of the EPSP (Lee et al., 2007; Mannaioni et al, 2008). In this context, loss of PAR1 function would result in less tonic activation of extrasynaptic NMDARs, thus impairing synaptic responses during LTP induction. This interpretation is further supported by the observation that an LTP-inducing stimulus delivered in the presence of both ifenprodil, a GluN2B-selective antagonist, and a PAR1 agonist failed to elicit LTP (Maggio et al., 2008). A recent study suggests that PAR1 activation in interneruons leads to an endocannabinoid-mediated suppression of inhibitory transmission (Hashimotodani et al., 2011). Thus, loss of PAR1 function would result in deficits in endocannabinoid-mediated suppression of feedforward inhibition during TBS. Collectively, these scenarios would account for the significantly reduced responses to TBS underlying the impaired LTP observed in PAR1 −/− mice.

Several lines of evidence suggest that loss of PAR1 is not detrimental to NMDAR function per se. First, NMDA-evoked current responses have been shown to be normal in PAR1 −/− mice (Gingrich et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2007). Second, we show here that NMDAR-mediated fEPSP responses and expression levels of NMDAR subunits in PAR1 −/− slices are not impaired. Further investigation is necessary to determine if our observations can be explained by impairments in NMDAR trafficking contributing to homeostatic plasticity (Pérez-Otaño and Ehlers, 2005; Zhao et al., 2008) or insertion of NMDARs in LTP (Grosshans et al., 2002; Watt et al., 2004; Lau and Zukin, 2007; Peng et al., 2010). The results from our LTP studies suggest that PAR1 is a novel mediator of activity-dependent processes.

Relation of results to previous studies

While a number of serine proteases can activate PAR1, the endogenous activator for PAR1 in the CNS has not yet been identified (O’Brien et al., 2001; Macfarlane et al., 2001; Noorbakhsh et al., 2003). A growing body of evidence, however, suggests that the tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)/plasminogen/plasmin system may serve as an endogenous PAR1 activator (Junge et al., 2003; Nagai et al., 2006; Ito et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2007; Mannaioni et al., 2008). In this system, the zymogen plasminogen is cleaved by tPA to the active serine protease, plasmin, which can activate PAR1 (Kuliopulos et al., 1999; Mannaioni et al., 2008).

In support of this idea, it is interesting that the memory formation deficits in the PAR1 −/− mice that we present here and in a previous study (Almonte et al., 2007) are consistent with previous observations that tPA −/− mice have deficits in multiple learning and memory tasks (Huang et al., 1996; Pawlak et al., 2002; Pawlak et al., 2005). Our slice electrophysiology results are also consistent with previously described effects of various components of the tPA/plasminogen/plasmin system. Deletion or inhibition of tPA resulted in impaired LTP in hippocampal slices, while application of exogenous tPA could rescue or enhance LTP (Huang et al., 1996; Baranes et al., 1998; Pang et al., 2004). We show that lack of PAR1 function in hippocampal slices results in significantly reduced LTP, which is attributable, in part, to a change in the absolute capacity for LTP. In support of this, previous work showed that activation of PAR1 through the application of plasminogen/plasmin, thrombin, or a PAR1-specific activating peptide, coupled with a subtreshold LTP stimulus is sufficient to induce LTP (Mizutani et al., 1996; Maggio et al., 2008).

PAR1 in astrocyte-neuron interactions

PAR1 expression in mammalian brains varies widely by region and cell type. In the nucleus accumbens, the ventral tegmental area (Nagai et al. 2006) and the striatum (Hamill et al., 2009), PAR1 is expressed in dopaminergic neurons. In the amygdala, PAR1 expression has been observed in both neurons and astrocytes (Weinstein et al., 1995; Striggow et al., 2001; Bourgognon and Pawlak, 2008). In some brain regions, such as the area CA1 of the hippocampus (Weinstein et al., 1995; Striggow et al., 2001; Junge et al., 2004), the entorhinal cortex (Gomez-Gonzalo et al., 2010), and the nucleus of the solitary tract (Hermann et al., 2009), PAR1 is preferentially expressed in astrocytes. There is a large body of evidence supporting the idea that activation of Gαq-coupled GPCRs in astrocytes can result in the vesicular release of neurotransmitters, such as ATP, glutamate, and D-serine, which can activate their cognate receptors on both presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons. This interplay between astrocytic activity and neuronal function has been called the “tripartite synapse” (for reviews, see Haydon and Carmignoto, 2006; Fellin et al., 2009, but also see Agulhon et al, 2008; Fiacco et al., 2009). Consistent with these observations, activation of PAR1 in astrocytes can lead to the release of ATP (Kreda et al., 2008) and glutamate, which can modulate synaptic responses (Lee et al., 2007; Mannaioni et al., 2008; Shigetomi et al., 2008; Hermann et al., 2009).

In addition to vesicular release, other release mechanisms in astrocytes, such as channel-mediated release, have been proposed (Fiacco et al., 2009; Hamilton and Attwell, 2010). It has recently been demonstrated that activation of astrocytic PAR1 leads to the activation of the calcium-activated anion channel Bestrophin-1, which shows permeability to Cl−, bicarbonate, and large anions such as GABA and glutamate (Park et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2010). These observations strongly suggest that, at least in the hippocampus, PAR1 may be a regulator of mechanisms underlying function of the tripartite synapse. Thus, we posit that PAR1 is a useful model for astrocyte-neuron interactions subserving NMDAR-dependent memory formation and synaptic function in the hippocampus (Almonte and Sweatt, 2011).

With support from recent observations that PAR2 activity can regulate motivational learning (Lohman et al., 2009) and epileptogenesis (Lohman et al., 2008), it is becoming increasingly apparent that PARs and their serine protease activators serve important roles in the formation of memories and in the control of synaptic function and plasticity (Almonte and Sweatt, 2011). A major caveat to the work presented here is that the PAR1−/− mice used in our experiments lack PAR1 in all cell types. Because of this, we cannot rule out compensatory actions by one or more of the other PAR family members. The use of a global knockout also does not allow us to ascertain the relative contributions of neuronal versus astrocytic PAR1 activation. For example, recent reports suggest that activation of neuronal PAR1 may control hippocampal excitability by suppression of inhibition via an endocannabinoid-mediated mechanism (Hashimotodani et al., 2011), or by enhanced depolarization of dentate granule cells (Han et al., 2011). However, additional reports demonstrate hippocampal PAR1 expression and responses only in astrocytes (Niego et al., 2011; Shavit et al., 2011). More work is clearly needed to resolve these observations.

For now, the debate on the physiological role of astrocyte-neuron signaling continues (Wenker, 2010). While the effects on NMDAR-dependent LTP we describe agree with the recent discovery that D-serine release from astrocytes can control LTP (Henneberger et al., 2010), they are in direct contrast to observations that Gαq-coupled GPCR-Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes and the putative vesicular release of neurotransmitters do not modulate LTP in hippocampal slices (Agulhon et al., 2010). Ultimately, the results presented here provide much insight into the contribution of PAR1 activity to normal brain function, and suggest PAR1 as a potential site for developing novel therapeutics for the treatment of addiction, traumatic brain injury, stroke, and cognition disorders.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Brandon Walters, Lynn Dobrunz (University of Alabama at Birmingham), Cendra Agulhon (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), and Stephen Traynelis (Emory University) for helpful discussions. We also thank Christopher Rex (University of California, Irvine) for help with theta-burst response analysis. We thank Kelsey Patterson and Dawn Eason (University of Alabama at Birmingham) for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grants MH57014, AG031722, NS057098, and funds from the Evelyn F. McKnight Brain Research Foundation.

List of abbreviations

- ACSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- AMPAR

α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionate receptor

- CNS

central nervous system

- fEPSP

field excitatory postsynaptic potential

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- NMDAR

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor

- PAR1

protease-activated receptor-1

- PTP

post-tetanic potentiation

- TBS

theta-burst stimulation

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agulhon C, Petravicz J, McMullen AB, Sweger EJ, Taves SR, Casper KB, Fiacco TA, McCarthy KD. What is the role of astrocyte calcium in neurophysiology? Neuron. 2008;59:932–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agulhon C, Fiacco TA, McCarthy KD. Hippocampal short- and long-term plasticity are not modulated by astrocyte Ca2+ signaling. Science. 2010;327:1250–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1184821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almonte AG, Hamill CE, Chhatwal JP, Wingo TS, Barber JA, Lyuboslavsky PN, Sweatt JD, Ressler KJ, White DA, Traynelis SF. Learning and memory deficits in mice lacking protease-activated receptor-1. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;88:295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almonte AG, Sweatt JD. Serine proteases, serine protease inhibitors, and protease-activated receptors: Roles in synaptic function and behavior. Brain Research. 2011;1407:101–22. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai A, Lynch G. Factors regulating the magnitude of long-term potentiation induced by theta pattern stimulation. Brain Research. 1992;598:173–184. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai A, Black J, Lynch G. Origins of the variations in long-term potentiation between synapses in the basal versus apical dendrites of hippocampal neurons. Hippocampus. 1994;4:1–10. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450040103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai AC, Xia YF, Suzuki E. Modulation of AMPA receptor kinetics differentially influences synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2004;123:1011–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahr BA, Staubli U, Xiao P, Chun D, Ji ZX, Esteban ET, Lynch G. Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser-selective adhesion and the stabilization of long-term potentiation: pharmacological studies and the characterization of a candidate matrix receptor. J Neurosci. 1997;14:1320–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-04-01320.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranes D, Lederfein D, Huan YY, Chen M, Bailey CH, Kandel ER. Tissue plasminogen activator contributes to the late phase of LTP and to synaptic growth in the hippocampus mossy fiber pawthway. Neuron. 1998;21:813–25. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31–9. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgognon JM, Pawlak R. Program No. 883.22 2008 Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Vol. 2008. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience; 2008. The role of protease-activated receptor-1 in mouse behavior. Online. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly AJ, Ishihara H, Kahn ML, Farese RV, Jr, Coughlin SR. Role of the thrombin receptor in development and evidence for a second receptor. Nature. 1996;381:516–9. doi: 10.1038/381516a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin SR. Thrombin signaling and protease-activated receptors. Nature. 2000;407:258–64. doi: 10.1038/35025229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JJ, Sweatt JD. DNA methylation and memory formation. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1319–23. doi: 10.1038/nn.2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond DM, Dunwiddie TV, Rose GM. Characteristics of hippocampal primed burst potentiation in vitro and in the awake rat. J Neurosci. 1988;8:4079–88. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-11-04079.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrunz LE, Stevens CF. Heterogeneity of release probability, facilitation, and depletion at central synapses. Neuron. 1997;18:995–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erreger K, Traynelis SF. Allosteric interaction between zinc and glutamate binding domains on NR2A causes desensitization of NMDA receptors. J Physiol. 2005;569:381–93. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.095497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erreger K, Traynelis SF. Zinc inhibition of NR1/NR2A N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. J Physiol. 2007;586:763–78. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellin T. Communication between neurons and astrocytes: relevance to the modulation of synaptic and network activity. J Neurchem. 2009;108:533–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiacco TA, Agulhon C, McCarthy KD. Sorting Out Astrocyte Physiology from Pharmacology. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;49:151–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich MB, Junge CE, Lyuboslavsky P, Traynelis SF. Potentiation of NMDA receptor function by the serine protease thrombin. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4582–95. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04582.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Gonzalo M, Losi G, Chiavegato A, Zonta M, Cammarota M, Brondi M, Vetri F, Uva L, Pozzan T, de Curtis M, Ratto GM, Carmignoto G. An excitatory loop with astrocytes contributes to drive neurons to seizure threshold. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Liu D, Gelbard H, Cheng T, Insalaco R, Fernandez JA, Griffin JH, Zlokovic BV. Activated protein C prevents neuronal apoptosis via protease activated receptors 1 and 3. Neuron. 2004;41:563–72. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans DR, Clayton DA, Coultrap SJ, Browning MD. LTP leads to rapid surface expression of NMDA but not AMPA receptors in adult rat CA1. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:27–33. doi: 10.1038/nn779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill CE, Goldshmidt A, Nicole O, McKeon RJ, Brat DJ, Traynelis SF. Special lecture: gilal reactivity after damage: implications for scar formation and neuronal recovery. Clin Neurosurg. 2005;52:29–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill CE, Caudle WM, Richardson JR, Yuan H, Pennell KD, Greene JG, Miller GW, Traynelis SF. Exacerbation of dopamine terminal damage in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease by the G-protein coupled receptor, PAR1. Mol Pharm. 2007;72:653–64. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.038158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill CE, Mannaioni G, Lyuboslavsky P, Sastre AA, Traynelis SF. Protease-activated recptor 1-dependent neuronal damage involves NMDA receptor function. Exp Neurol. 2009;217:136–46. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton NB, Attwell D. Do astrocytes really exocytose neurotransmitters? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:227–38. doi: 10.1038/nrn2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han KS, Mannaioni G, Hamill CE, Lee J, Junge CE, Lee CJ, Traynelis SF. Activation of protease activated receptor 1 increases the excitability of the dentate granule neurons of hippocampus. Molecular Brain. 2011;4:32. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-4-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimotodani Y, Ohno-Shosaku T, Yamakazi M, Sakimura K, Kano M. Neuronal protease-activated receptor 1 drives synaptic retrograde signaling mediated by the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol. J Neurosci. 2011;31:3104–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6000-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon PG, Carmignoto G. Astrocyte control of synaptic transmission and neurovascular coupling. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:1009–31. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00049.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henneberger C, Papouin T, Oliet SH, Rusakov DA. Long-term potentiation depends on release of D-serine from astrocytes. Nature. 2010;463:232–6. doi: 10.1038/nature08673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann GE, Van Meter MJ, Rood JC, Rogers RC. Proteinase-activated receptors in the nucleus of the solitary tract: evidence for glial-neural interactions in autonomic control of the stomach. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9292–300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6063-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Bach ME, Lipp HP, Zhuo M, Wolfer DP, Hawkins RD, Schoonjans L, Kandel ER, Godfraind JM, Mulligan R, Collen D, Carmeliet P. Mice lacking the gene encoding tissue-type plasminogen activator show a selective interference with late-phase long-term potentiation in both Schaffer collateral and mossy fiber pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8699–704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Nagai T, Mizoguchi H, Fukakusa A, Nakanishi Y, Kamei H, Nabeshima T, Takuma K, Yamada K. Possible involvement of protease-activated receptor-1 in the regulation of morphine-induced dopamine release and hyperlocomotion by the tissue plasminogen activator-plasmin system. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1392–1399. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junge CE, Sugawara T, Mannaioni G, Alargamsy S, Conn PJ, Brat DJ, Chan PH, Traynelis SF. The contribution of protease-activated receptor 1 to neuronal damage caused by transient focal cerebral ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:13019–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235594100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junge CE, Lee CJ, Hubbard KB, Zhang Z, Olson JJ, Hepler JR, Brat DJ, Traynelis SF. Protease-activated receptor-1 in human brain: localization and functional expression in astrocytes. Exp Neurol. 2004;188:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramar EA, Lin B, Lin CY, Arai AC, Gall CM, Lynch G. A novel mechanism for the facilitation of theta-induced long-term potentiation by brain-derived neruotrophic factor. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5151–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0800-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreda SM, Seminario-Vidal L, Heusden CV, Lazarowski ER. Thrombin-promoted release of UDP-glucose from human astrocytoma cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:1528–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuliopulos A, Covic L, Seeley SK, Sheridan PH, Helin J, Costello CE. Plasmin desensitization of the PAR1 thrombin receptor: kinetics, sites of truncation, and implications for thrombolytic therapy. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4572–85. doi: 10.1021/bi9824792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson J, Wong D, Lynch G. Patterned stimulation at the theta frequency is optimal for the induction of hippocampal long-term potentiation. Brain Res. 1986;19:347–50. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson J, Lynch G. Induction of synaptic potentiation in hippocampus by patterened stimulation involves two events. Science. 1986;232:985–8. doi: 10.1126/science.3704635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson J, Lynch Role of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in the induction of synaptic potentiation by burst stimulation patterened after the hippocampal θ-rhythm. Brain Research. 1988;441:111–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91388-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau CG, Zukin RS. NMDA receptor trafficking in synaptic plasticity and neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:413–26. doi: 10.1038/nrn2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CJ, Mannaioni G, Yuan H, Woo DH, Gingrich MB, Traynelis SF. Astrocytic control of synaptic NMDA receptors. J Physiol. 2007;581:1057–81. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.130377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Yoon BE, Berglund K, Oh SJ, Park H, Shin SH, Augustine GJ, Lee CJ. Channel-mediated tonic GABA release from glia. Science. 2010;330:790–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1184334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman RJ, O’Brien TJ, Cocks TM. Protease-activated receptor-2 regulates trypsin expression in the brain and protects against seizures and epileptogenesis. Neurbiol Dis. 2008;30:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman RJ, Jones NC, O’Brien TJ, Cocks TM. A regulatory role for protease-activated receptor-2 in motivational learning in rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;92:301–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane SR, Seatter MJ, Kanke T, Hunter GD, Plevin R. Proteinase-activated receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:245–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggio N, Shavit E, Chapman J, Segal M. Thrombin induces long-term potentiation of reactivity to afferent stimulation and facilitates epileptic seizures in rat hippocampal slices: toward understanding the functional consequences of cerebrovascular insults. J Neurosci. 2008;28:732–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3665-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannaioni G, Orr AG, Hamill CE, Yuan H, Pedone KH, McCoy KL, Palmini RB, Junge CE, Lee CJ, Yepes M, Hepler JR, Traynelis SF. Plasmin Potentiates Synaptic N-Methyl-D-aspartate Receptor Function in Hippocampal Neurons through Activation of Protease-activated Receptor-1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20600–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803015200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CA, Sweatt JD. Covalent modification of DNA regulates memory formation. Neuron. 2007;53:857–69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani A, Saito H, Matsuki N. Possible involvement of plasmin in long-term potentiation of rat hippocampal slices. Brain Res. 1996;739:276–81. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00834-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Lynch G. Long-term potentiation differentially affects two components of synaptic responses in hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:9346–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T, Ito M, Nakamichi N, Mizoguchi H, Kamei H, Fukakusa A, Nabeshima T, Takuma K, Yamada K. The rewards of nicotine: regulation by tissue plasminogen activator-plasmin system through protease activated receptor-1. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12374–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3139-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicole O, Goldshmidt A, Hamill CE, Sorensen SD, Sastre A, Lyuboslavsky P, Hepler JR, McKeon RJ, Traynelis SF. Activation of protease-activated receptor-1 triggers astrogliosis after brain injury. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4319–29. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5200-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Expression mechanisms underlying NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;868:515–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niclou SP, Suidan HS, Pavlik A, Vejsada R, Monard D. Changes in the expression of protease-activated receptor 1 and protease nexin-1 mRNA during rat nervous system development and after nerve lesion. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:1590–607. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niego B, Samson AL, Petersen KU, Medcalf RL. Thrombin-induced activation of astrocytes in mixed rat hippocampal cultures is inhibited by soluble thrombomodulin. Brain Res. 2011;1381:38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noorbakhsh F, Vergnolle N, Hollenberg MD, Power C. Proteinase-activated receptors in the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:981–90. doi: 10.1038/nrn1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien PJ, Molino M, Kahn M, Brass LF. Protease activated receptors: theme and variations. Oncogene. 2001;20:1570–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson EE, Lyuboslavsky P, Traynelis SF, McKeon RJ. PAR-1 deficiency protects against neuronal damage and neurological deficits after unilateral cerebral hypoxia/ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:964–71. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000128266.87474.BF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang PT, Teng HK, Zaitsev E, Woo NT, Sakata K, Zhen S, Teng KK, Yung WH, Hempstead BL, Lu B. Cleavage of proBDNF by tPA/plasmin is essential for long-term hippocampal plasticity. Science. 2004;306:487–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1100135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H, Oh SJ, Han KS, Woo DH, Park H, Mannaioni G, Traynelis SF, Lee CJ. Bestrophin-1 encodes for the Ca2+-activated anion channel in hippocampal astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13063–73. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3193-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak R, Nagai N, Urano T, Napiorkowska-Pawlak D, Ihara H, Takada Y, Collen D, Takada A. Rapid, specific and active site-catalyzed effect of tissue-plasminogen activator on hippocampus-dependent learning in mice. Neuroscience. 2002;113:995–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak R, Rao BS, Melchor P, Chattarji S, McEwen B, Strickland S. Tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen mediate stress-induced decline of neuronal and cognitive functions in the mouse hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18201–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509232102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, Zhao J, Gu QH, Chen RQ, Xu Z, Yan JZ, Wang SH, Liu SY, Chen Z, Lu W. Distinct trafficking and expression mechanisms underlie LTP and LTD of NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic responses. Hippocampus. 2010;20:646–58. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Otaño I, Ehlers MD. Homeostatic plasticity and NMDA receptor trafficking. Trends Neurosci. 2005;25:229–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran R, Hollenberg MD. Proteinases and signalling: pathophysiological and therapeutic implications via PARs and more. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:S263–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selcher JC, Weeber EJ, Christian J, Nekrasova T, Landreth GE, Sweatt JD. A role for ERK MAP kinase in physiologic temporal integration in hippocampal area CA1. Learn Mem. 2003;10:26–39. doi: 10.1101/lm.51103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavit E, Michaelson DM, Chapman J. Anatomical localization of protease-activated receptor-1 and protease-mediated neuroglial crosstalk on peri-synaptic astrocytic endfeet. J Neurochem. 2011;119:460–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigetomi E, Bower DN, Sofroniew MV, Khakh BS. Two forms of astrocyte calcium excitability have distinct effects on NMDA receptor-mediated slow inward currents in pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6659–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1717-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striggow F, Riek-Burchardt M, Kiesel A, Schmidt W, Henrich-Noack P, Breder J, Krug M, Reymann KG, Reiser G. Four different types of protease-activated receptors are widely expressed in the brain and are up-regulated in hippocampus by severe ischemia. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:595–608. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweatt JD. The neuronal MAP kinase cascade: a biochemical signal integration system subserving synaptic plasticity and memory. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweatt JD. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in synaptic plasticity and memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:311–7. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweatt JD. Mechanisms of Memory. 2. London, UK: Elsevier Academic Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tongiori E, Ferrero F, Cattaneo A, Domenici L. Dark-rearing decreases NR2A N-methyl-D-aspartate subunit in all visual cortical layers. Neuroscience. 2003;119:1013–22. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00196-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynelis SF, Wollmuth LP, McBain CJ, Menniti FS, Vance KM, Ogden KK, Hansen KB, Yuan H, Myers SJ, Dingledine R. Glutamate receptor ion channels: structure, regulation, and function. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:405–96. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DL, Davis M. The role of amygdala glutamate receptors in fear learning, fear-potentiated startle, and extinction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:379–92. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt AJ, Sjostrom PH, Hausser M, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. A proportional but slower NMDA potentiation follows AMPA potentiation in LTP. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:518–24. doi: 10.1038/nn1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein JR, Gold SJ, Cunningham DD, Gall CM. Cellular localization of thrombin receptor mRNA in rat brain: expression by mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons and codistribution with prothrombin mRNA. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2906–19. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02906.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenker I. An active role for astrocytes in synaptic plasticity? J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:1216–8. doi: 10.1152/jn.00429.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock JR, Heynen AH, Shuler MG, Bear MF. Learning induces long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Science. 2006;313:1093–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1128134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Peng Y, Xu Z, Chen RQ, Gu QH, Chen Z, Lu W. Synaptic metaplasticity through NMDA receptor lateral diffusion. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3060–70. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5450-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]