Abstract

The question as to why the macula of the retina is prone to an aging disease (age-related macular degeneration) remains unanswered. This unmet challenge has implications since AMD accounts for approximately 54% of blindness in the USA (Swaroop, Chew, Bowes Rickman and Abecasis, 2009). While AMD has onset in the elder years, it likely develops over time. Genetic discovery to date has accounted for approximately 50% of the inheritable component of AMD. The polymorphism that has been most widely studied is the Y402H allele in the complement factor H gene. The implication of this genetic association is that in a subset of AMD cases, unregulated complement activation is permissive for AMD. Given that this gene variant results in an amino acid substitution, it is assumed that this change will have functional consequences although the precise mechanisms are still unknown. Genetic predisposition is not the only factor however, since in this complex disease there is substantial evidence that lifestyle factors such as diet and smoking contribute to risk. Here we provide an overview of current knowledge with respect to factors involved in AMD pathogenesis. Interwoven with these issues is a discussion of the significant role played by aging processes, some of which are unique to the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. One recurring theme is the potential for disease promotion by diverse types of oxidation products.

Keywords: Age-related macular degeneration, Complement system, Drusen, Retinal pigment epithelium

1. Genetic associations with AMD

Susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration is determined by multiple factors that include both inherited and environmental influences. Indications for genetic association were initially provided by several studies linking AMD to multiple chromosomal loci (Seddon et al., 2003; Weeks et al., 2004). This evidence eventually lead to case-control single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis and either genome wide or candidate gene strategies revealing that some of the susceptibility could be assigned to alleles and haplotypes on genes encoding proteins of the complement system. The first complement-related gene to be identified was complement factor H (chromosome 1q31) and several variants and haplotypes have been shown to modify AMD risk. Amongst this group are common alleles conferring increased susceptibility (for instance, Y402H) (Edwards et al., 2005; Hageman et al., 2005; Haines et al., 2005; Klein et al., 2005), variants such as IVS1 and IS6 that are protective (Ferrara et al., 2008), and a rare variant exhibiting high risk (Raychaudhuri et al., 2011). Protective haplotypes on CFH-related proteins (Hageman et al., 2006; Hughes et al., 2006) have also been reported (Edwards et al., 2005; Hageman et al., 2005; Haines et al., 2005; Klein et al., 2005). Two non-synonymous polymorphisms in C3 were also found to be associated with AMD (Yates et al., 2007) as was a single polymorphism in complement factor I (Fagerness et al., 2009). A common haplotype containing genes for both C2 and BF of the classical and alternative pathways, respectively, has been reported to have a protective effect (Gold et al., 2006). Since the associated variants in C2 and BF are in linkage disequilibrium, the genetic studies cannot discriminate between them and involvement of the classical pathway cannot be excluded. In this regard it is worth noting that even in the case of a stimulus that activates complement via the classical pathway, amplification is dependent on the alternative pathway.

A gene or genes on chromosome 10 (10q, ARMS2/HTRA1) have a particularly strong association with AMD (Rivera et al., 2005; Weeks et al., 2004) but the specific gene and its function have not yet been clarified and there is no reason to assume at this time that complement related mechanisms are involved. Additional disease-related genes include an AMD-associated locus at 22q12.3 near the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 gene (Chen et al., 2010), the episilon3 allele of apolipoprotein E (Baird et al., 2004), and the hepatic lipase gene that participates in the high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) pathway (Neale et al., 2010). Smoking, a strongly associated environmental factor, does not interact with known AMD gene loci (Ryu et al., 2010; Sofat et al., 2012) except for apolipoprotein E (Adams et al., 2012). However, together with dietary factors (Seddon et al., 1994), the association with smoking likely indicates that oxidative mechanisms are involved in the disease processes culminating in AMD. Interested readers are referred to the existing literature for a comprehensive review of anti-oxidant status, diet, and smoking as relates to AMD (Cai et al., 2000; Fletcher et al., 2008; Galor and Lee, 2011; Khandhadia and Lotery, 2010; Krishnadev et al., 2010).

2. Bruch’s membrane deposits and drusen in aging and AMD

The genetic evidence for complement pathway involvement in AMD had been preceded by studies indicating ongoing complement activation in Bruch’s membrane and drusen, the focal extracellular deposits that form below RPE cells and that confer increased risk for AMD. Specifically, a number of complement proteins, activation products and negative regulators of complement were detected amongst the molecular constituents of the diffuse and focal deposits (Anderson et al., 2002; Crabb et al., 2002; Donoso et al., 2006; Hageman et al., 2001; Nozaki et al., 2006). Other drusen constituents are consistent with a role for oxidative insult in AMD pathogenesis. The latter group includes carboxyethylpyrrole protein (CEP)-adducts. These protein modifications are generated by fragments released following the oxidation of docosahexaenoate-containing lipids in photoreceptor cells (Crabb et al., 2002). Autoantibodies to CEP are also elevated in blood samples obtained from AMD patients (Gu et al., 2009). Moreover, immunization of mice with albumin adducted to CEP leads to a complement-mediated attack on outer retina/Bruch’s membrane (Hollyfield et al., 2008). Proteins modified by advanced glycation end (AGE)-products are yet another feature of sub-RPE deposits (Cano et al., 2011; Crabb et al., 2002; Farboud et al., 1999; Handa et al., 1998, 1999; Tian et al., 2005; Yamada et al., 2006). More recent findings indicate that the dicarbonyls responsible for AGE-formation are likely bisretinoid photodegradation products released from overlying RPE cells (discussed below).

Bruch’s membrane also undergoes a process of neutral lipid accumulation that is characterized by an abundance of esterified cholesterol that likely originates from RPE cells as components of apoliprotein-B lipoprotein assemblies (Curcio et al., 2011). As lipoproteins are retained in Bruch’s membrane, a lipid wall develops external to the RPE basal lamina, but why this scenario unfolds is not known. Recent evidence has linked AGE-deposition in Bruch’s membrane to mechanisms involved in lipoprotein particle accumulation (Cano et al., 2011). Within the lipoprotein aggregates present in Bruch’s membrane, 7-ketocholesterol has been detected (Rodríguez and Larrayoz, 2010). This oxidized form of cholesterol can form non-enzymatically by reaction with singlet oxygen or by free radical mechanisms involving transition metals. Moreover, 7-ketocholesterol induces the transcription of a number of cytokines and can trigger reactive oxygen production by upregulated NADPH oxidase 4 (Rodríguez and Larrayoz, 2010). Yet another feature of drusen is the deposition of amyloid-β (Dentchev et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2002). This phenotype is replicated in APOE targeted-replacement mice that are fed a cholesterol-enriched high fat diet (Ding et al., 2011). It is significant that amyloid-β is reported to activate complement (Kurji et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2009).

2.1. RPE cells as the nexus

AMD ultimately involves pathology in photoreceptors cells, RPE, Bruch’s membrane and choriocapillaris but RPE cell dysfunctioning and loss is usually considered to be the primary insult in atrophic AMD (Sarks et al., 1988). For example, recent histological studies have shown that the loss of RPE precedes the atrophy of choroidal vasculature (McLeod et al., 2009; Sarks et al., 1988) and at least some constituents of drusen originate from RPE (discussed above). Impairment of antioxidant defense (Newsome et al., 1994), mitochondria dysfunctioning (Jarrett et al., 2008; Karunadharma et al., 2010) and altered proteomic profiles due to modified substrate (Bruch’s membrane) (Glenn et al., 2012) are some of the factors that may contribute to the decline in RPE health.

It is often assumed that the accumulation of lipofuscin by RPE reflects age-related lysosomal dysfunctioning. However, since healthy eyes of all ages amass this fluorescent material, lysosomal failure is not the most parsimonious explanation. The lipofuscin fluorophores that have been identified form by inadvertent reactions of all-trans-retinal in photoreceptor outer segments. This complex mixture of diretinals includes A2E (Sparrow et al., 2011). Since the diretinal compounds of RPE lipofuscin are excited by wavelengths in the visible range, efforts to understand the damaging effects of RPE lipofuscin have lead to studies of the photoreactivity of these fluorescent compounds. Production of singlet oxygen and superoxide anion within RPE lipofuscin has been demonstrated by a number of studies (Ben-Shabat et al., 2002; Gaillard et al., 1995, 2004; Pawlak et al., 2003; Reszka et al., 1995; Rozanowska et al., 1995, 1998; Cantrell et al., 2001; Kanofsky et al., 2003; Lamb et al., 2001; Ragauskaite et al., 2001). It has been suggested that A2E is also excited by energy transfer from other blue-light absorbing lipofuscin fluorophores (Haralampus-Grynaviski et al., 2003); whether the latter agents are other characterized bisretinoids is not known. Lipofuscin bisretinoids such as A2E and all-trans-retinal dimer also react with singlet oxygen (Ben-Shabat et al., 2002; Roberts et al., 2002). It is likely due to this quenching behavior that A2E was previously considered to be a weak photosensitizer of singlet oxygen. There is good evidence indicating that these photooxidative processes described above occur in vivo. Specifically, A2E photooxidized at varying numbers of carbon–carbon double bonds are detected in extracts from human and mouse eyes (Dillon et al., 2004; Jang et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2007; Radu et al., 2004). Bisretinoid photooxidation and photocleavage upon exposure to wavelengths of light that reach the retina, also explains the observation that photobleaching of RPE lipofuscin has been observed during fluorescence imaging of the RPE monolayer in non-human primates (Hunter et al., 2012; Morgan et al., 2009). This photobleaching occurs despite the use of light levels that are well within light safety standards (Hunter et al., 2012; Morgan et al., 2009) and thus may indicate that RPE cells may be more susceptible to these processes than previously thought.

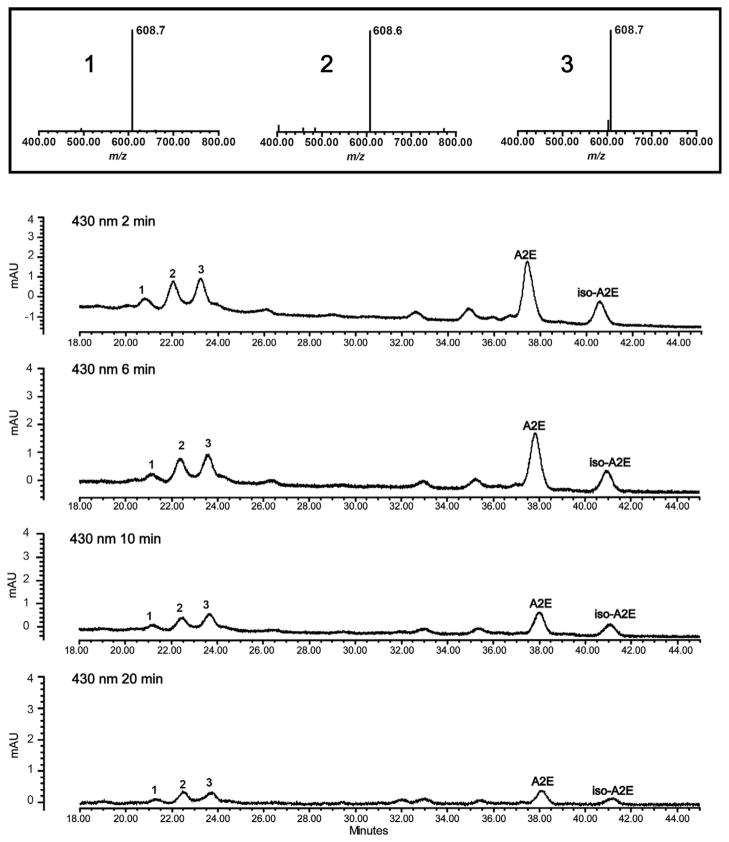

Photooxidized species of A2E do not accumulate with time however, since with continued oxygen addition photofragmentation occurs (Fig. 1). Indeed photolysis of bisretinoid molecules following photooxidation likely explains the observation that photooxidized forms of A2E do not accumulate with age (Grey et al., 2011). Moreover, the harmful effects (Schutt et al., 2000; Sparrow et al., 2000) mediated by the photooxidation of bisretinoid (Ben-Shabat et al., 2002; Sparrow et al., 2002) likely results from photooxidation-induced lysis of bisretinoid resulting in the release of aldehyde-bearing cleavage products (Wang et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2010). The latter includes methylglyoxal and glyoxal, small, reactive oxoaldehydes well known to form advanced glycation end (AGE) products. In chronic diseases such as diabetes and atherosclerosis, methylglyoxal and glyoxal form as intermediates in non-enzymatic glycation and oxidation reactions leading to AGE-modification of proteins (Rabbani and Thornalley, 2008). The release of MG and GO from photodegraded bisretinoid such as A2E is significant since AGE-adducted proteins are also detected in drusen that accumulate below RPE cells in vivo; drusen are a major risk factor for AMD progression (Farboud et al., 1999; Glenn et al., 2007; Handa et al., 1999; Ishibashi et al., 1998). Bisretinoid photocleavage upon exposure to wavelengths of light that reach the retina, is a previously unknown source of methylglyoxal and glyoxal and the most parsimonious explanation for the origin of the dicarbonyls that play a role in drusen formation. These findings also indicate a link between RPE lipofuscin photooxidation and drusen formation.

Fig. 1.

A2E photooxidation and photodegradation. UPLC-ESI/MS, (ultra performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization/mass spectrometry) detection of A2E and oxidized A2E in ARPE-19 cells that accumulated A2E and were irradiated for 2, 6, 10 and 20 min. The more polar photooxidized forms of A2E elute ahead of the parent A2E and isoA2E compounds. Shown are three chromatographic peaks that on the basis of molecular weight (m/z 608; insets above) can be identified as mono-oxidized A2E (molecular weight of A2E, 592; 592 + 16; m/z 608). Reductions in peak areas of A2E/isoA2E under conditions of 430 nm irradiation are indicative of A2E photooxidation/photodegradation. Note that as the duration of irradiation is extended, A2E/isoA2E peak areas decrease as a result of photooxidation; yet the areas of the m/z 608 peaks do not increase because of photodegradation.

3. Complement components in RPE-Bruch’s membrane–choroid complex

3.1. Expression of complement related proteins

The complement cascade is a mechanism for enabling innate immune defense and involves the processing of multiple inactive zymogens to form active proteases or effectors (Zipfel and Skerka, 2009). The latter components are primarily synthesized in the liver with delivery via the circulation, but local production in some tissues can also occur. For instance, quantitative PCR analysis has shown that the RPE-choroid is able to synthesize a broad range of complement components and regulators. RPE expresses the mRNA for complement 3(C3), complement factor B (CFB), CFH, CFD and CFI (Anderson et al., 2010). Complement related proteins expressed within the choroid are of an even broader range and of greater abundance (Anderson et al., 2010). The alternative pathway of complement activates on surfaces unprotected by complement regulatory proteins. Thus the RPE cell also expresses membrane-associated inhibitors such as MCP (membrane cofactor protein, CD46), DAF (decay accelerating factor, CD 55) and lower levels of CD59 (Anderson et al., 2010). ‘Treatment of ARPE-19 cells with hydrogen peroxide in a culture model, has been shown to reduce cell surface content of complement inhibitors DAF, CD55 and CD59 that otherwise are expressed by this cell line (Thurman et al., 2009). This finding suggests that RPE cells exposed to oxidative insult are permissive for complement activation on their surfaces. A recent case-control studies has reported an absence of an association between AMD and gene variants in CD46, CD55 and CD59 (Cipriani et al., 2012).

3.2. Initiating events

Given that dysregulation of the complement system likely underlies AMD pathogenesis in many cases, it has been suggested by some investigators that AMD is a systemic disease with manifestations in the macula (Scholl et al., 2008). Other researchers propose that the disease has a predilection for the macula due to the presence there of specific initiators of complement activity (Swaroop et al., 2009). Activators of the complement alternative pathway can include organic and inorganic particles and microorganisms. Thus, chronic low-grade Chlamydia infection has been considered as a possible trigger. Indeed, some case-control studies have found an association with exposure to Chlamydia pneumonia (Ishida et al., 2003; Kalayoglu et al., 2003), while others have not (Robman et al., 2005). It was also reported that subjects homozygous for the risk allele of CFH (CC) and who also presented with the upper tertile of antibody titers to C. pneumoniae had the highest increased odds of disease progression (11.8-fold) as compared to those with the lowest tertile of antibody titer and the TT genotype (Baird et al., 2008). More recently, no relationship has been found between IgG seropositivity for three Chlamydia (C) species (C. pneumonia, C. trachomatis and C. psittaci) and AMD status or severity in patients carrying risk alleles for CFH or HTRA1 (Khandhadia et al., 2012).

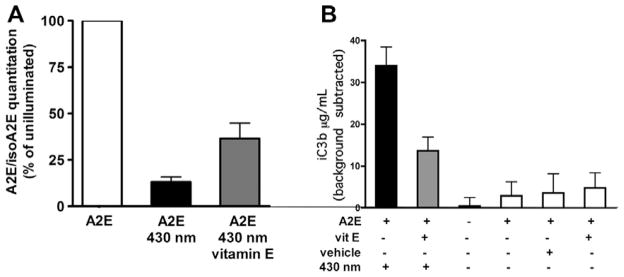

Several constituents of drusen could incite complement activation locally. For instance, as noted above, In AMD patients, amyloid-β is present in drusen (Dentchev et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2002); amyloid is also a known activator of complement. Additionally, 7-ketocholesterol has been shown in a number of systems to be a potent initiator of inflammation and is thus a likely contributor to disease processes within Bruch’s membrane (Rodríguez and Larrayoz, 2010). CEP- and AGE-adducts (discussed above) are additional candidates. We previously suggested that photodegradation products of RPE lipofuscin bisretinoids might trigger complement activation in a sustained low grade manner at the RPE-Bruch’s membrane interface. We demonstrated using both ARPE-19 and human fetal RPE cells that had accumulated A2E, that the generation of iC3b and C3a split products in overlying serum was light exposure dependent, was independent of apoptosis and was inhibited by depletion of factor B (Zhou et al., 2006, 2009). The events leading to complement activation are clearly related to oxidation, since as shown in Fig. 2, pre-treatment of the cells with vitamin E, not only attenuated photooxidation, this antioxidant also suppressed iC3b generation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Vitamin E decreases photooxidation and photodegradation of A2E and suppresses complement activation. ARPE-19 cells that had accumulated A2E were pre-treated or untreated with vitamin E (100 μM) for 24 h before 430 nm irradiation. (A) Pre-treatment with vitamin E reduces A2E photooxidation when cells are irradiated at 430 nm. A2E was quantified by HPLC with reference to known quantities of authentic A2E. The photooxidation of A2E is reflected in the reduced content of A2E in a sample after 430 nm illumination. The loss of A2E was diminished in the presence of vitamin E. (B) iC3b generation in serum overlying A2E-containing RPE was measured by enzyme immunoassay. iC3b production is reduced when the cells had been pre-treated with vitamin E. iC3b content in serum incubated in an otherwise empty well was subtracted as background. Mean ± SEM of five experiments; duplicate wells per experiment.

In experiments complementary to these findings, Radu et al., have reported that in eyecups harvested from Abca4 null mutant mice that exhibit intensified accumulation of RPE lipofuscin pigments such as A2E, increased complement activation relative to wild-type mice is evinced by the presence of C3 protein and its split products (Radu et al., 2011). They also observed a lipofuscin-related increase in C-reactive protein that may be consistent with the ability of C-reactive protein to suppress complement activation in the in vitro assay described above (Zhou et al., 2009). Cell surface negative regulators of complement activity were also downregulated on RPE cells in Abca4−/− mice (Radu et al., 2011).

3.3. Understanding the role of complement factor H

CFH is an important suppressor of the alternative complement pathway and it inhibits in both the fluid phase and at cell surfaces. Despite scores of genetic studies, it is still not known whether or how functional differences between 401H and 402Y contribute to AMD onset and/or progression. CFH is a large (155 kilodaltons) glycoprotein that circulates in human plasma at concentrations that are reported to vary from 250–800 μG/ml (Perkins et al., 2010; Scholl et al., 2008). The CFH gene contains 20 contiguous complement control protein (CCP) modules (short consensus repeats, SCR) each of which encodes peptide domains of approximately 60 amino acids. CFH functions are conferred by sites that extend along 1–4 domains. CCP modules 1–4 in the amino terminus region appear to be responsible for the cofactor (i.e. factor I-mediated conversion of C3b to the inactive iC3b) and decay accelerating (promoting the dis-association of the C3 cleavage enzyme C3bBb) activity of CFH and bind C3b with modest affinity (Boona et al., 2009). At cell surfaces CFH binds via its C-terminus to cell surface polyanions such as sialic acid, heparin and other glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) (Atkinson and Goodship, 2007). This self/non-self discrimination occurs predominantly though binding to CCP modules 7 and/or 19–20 (Aslam and Perkins, 2001; Kirkitadze and Barlow, 2001). The CCP 7 module also houses the single nucleotide polymorphism (T1277C) that results in the amino acid substitution of histidine for tyrosine at amino acid 402 (Atkinson and Goodship, 2007). In persons heterozygous or homozygous for this polymorphism, risk for AMD is increased approximately 5- and 7-fold, respectively (Klein et al., 2005). The CCP 7 domain also contains binding sites for C-reactive protein (CRP), heparin and streptococcal M6 protein (Giannakis et al., 2003). Several studies have shown that recombinant CFH fragments or full length CFH that includes CCP 7 carrying the CFH402H variant exhibit reduced affinity for heparin, CRP, DNA and necrotic cells (Herbert et al., 2007; Laine et al., 2007; Ormsby et al., 2008; Sjoberg et al., 2007). On the other hand, high serum CRP levels and the Y402H polymorphism in CFH are independently associated with AMD risk (Seddon et al., 2010).

Besides being synthesized in liver, factor H protein is secreted locally by RPE cells (Kim et al., 2009). This expression is further increased in response to interferon-γ and reduced under conditions of oxidative stress (Wu et al., 2007). Clearly therefore, RPE cells are able to regulate their production of complement components.

The role of CFH in retina is complex. For instance, mice with a null deletion in CFH exhibit photoreceptor cell degeneration and C3 deposition in association with RPE and photoreceptor outer segments but surprisingly, Bruch’s membrane is thinner than in wild-type mice (Coffey et al., 2007). On the other hand, it was reported that substitution of mouse Cfh domains CCP 6–8 by the human sequence resulted in sub-RPE deposits whether it was the Y402 or 402H variant (Ufret-Vincenty et al., 2010).

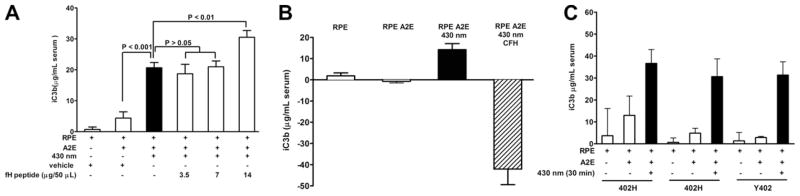

As illustrated in Fig. 3, we investigated the effects of a recombinant peptide encompassing CCP 6, 7 and 8 on iC3b production in serum exposed to ARPE-19 cells undergoing photodegradation. We found that addition of the peptide had no effect on iC3b production when delivered at concentrations of 3.5 and 7 μG/50 μl (Fig. 3A). However, at the higher concentration of 14 μG/50 μl, iC3b levels were increased perhaps because peptide binding interfered with serum CFH binding to the cells. On the other hand, when we delivered whole CFH protein (500 μG/ml) to the cells, iC3b elevation in response to A2E photodegradation was abrogated (Fig. 3B). We also examined for effects of serum obtained from AMD patients homozygous for the CFH H402 variant versus a non-AMD individual carrying the Y402 variant (Fig. 3C). Whether the normal human serum utilized in the assay carried CFH bearing the risk-H402 or Y402 variant, no difference in the production of iC3b was observed. Serum CFH levels in these individuals were 736 (402H), 635 (402H), and 688 (Y402) μG/ml.

Fig. 3.

Complement activation in the presence of complement factor H (CFH) peptide, CFH protein and CFH Y402H polymorphisms. ARPE-19 cells that had accumulated A2E were irradiated to cause photooxidation and photodegradation of A2E. Complement activation was monitored by measuring production of the C3 cleavage product iC3b in normal human serum overlying the RPE cells; iC3b was measured by enzyme immunoassay as described (Zhou et al., 2006). Serum incubated in empty wells was subtracted as background. Mean ± SEM; three experiments, duplicate wells per experiment; +, presence of condition. (A) A recombinant human peptide encompassing CCP 6, 7 and 8 of CFH (gift of Dr. Michael K. Pangburn, University of Texas Health Science Center) was added to normal human serum before irradiation. The Y402H polymorphism resides in CCP 7 and the peptide carried the Y402 form. (B) Whole human CFH (Quidel, San Diego CA) was added to normal human serum before irradiation. (C) Complement activation in the presence of serum obtained from donors with risk CFH 402H polymorphism (genotype 1277CC) and non-risk CFH Y402 variant (genotype 1277TT).

The question remains as to whether the Y402H polymorphism is a causal site or whether because of linkage disequilibrium, it serves as a marker of another causal variant (Sofat et al., 2012). The possibility also remains that CFH subserves non-traditional roles in the RPE-Bruch’s membrane milieu. For instance, CFH can bind malondialdehyde (MDA) (Weismann et al., 2011), a lipid peroxidation product. Interestingly, the 402H polymorphism also reduced the ability of CFH to bind MDA. MDA is postulated to serve as a danger signal to innate immune receptors, is detected in drusen and has been shown to be deposited in an underlying substrate when intra-RPE bisretinoid photodegrades (Zhou et al., 2005).

4. Concluding remarks

A range of treatments are currently under investigation for exudative and atrophic AMD. These include treatments undergoing pre-clinical study and early-stage clinical trials. Evidence that the complement system is permissible for disease development leading to AMD, has captured the interest of investigators who recognize the potential for complement components to be the focus of novel therapeutics. Some of these drugs include a small molecule inhibitor of C3 (POT-4), antibodies and aptamers against C5 and antibodies to factor D (Charbel Issa et al., 2009; Troutbeck et al., 2012; Zarbin and Rosenfeld, 2010). The importance of correcting what might be failed complement regulation in AMD, without adversely suppressing complement-related immunity, is recognized. Other remedies currently under study are visual cycle modulators that target RPE lipofuscin, anti-inflammatory agents, antioxidants and of course anti-angiogenic compounds that could act at any of the various steps involved in antiogenesis (Zarbin and Rosenfeld, 2010). There is also expectation of therapeutic cross-over from other disorders such as diabetes or Alzheimer’s disease. In the case of Alzheimer’s disease, it is interesting that although Alzheimer’s disease and AMD are both disorders of the elderly with some common pathological and biochemical and environmental features (Ohno-Matsui, 2011), the same genetic models do not apply (Proitsi et al., in press). Links between RPE lipofuscin and drusen formation could be reflected in the propensity for RPE lipofuscin photodegradation to release the dicarbonyls that form AGE-adducts on proteins found in drusen. In this case, dicarbonyl trapping agents may have application to AMD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants EY12951 (JRS) and P30EY019007 and a grant from Research to Prevent Blindness to the Department of Ophthalmology.

References

- Adams MK, Simpson JA, Richardson AJ, English DR, Aung KZ, Makeyeva GA, Guymer RH, Giles GG, Hopper J, Robman LD, Baird PN. Apolipoprotein E gene Associations in Age-related macular degeneration: the melbourne collaborative cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175 (6):511–518. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DH, Mullins RF, Hageman GS, Johnson LV. A role for local inflammation in the formation of drusen in the aging eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:411–431. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01624-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DH, Radeke MJ, Gallo NB, Chapin EA, Johnson PT, Curletti CR, Hancox LS, Hu J, Ebright JN, Malek G, Hauser MA, Rickman CB, Bok D, Hageman GS, Johnson LV. The pivotal role of the complement system in aging and age-related macular degeneration: hypothesis re-visited. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29:95–112. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslam M, Perkins SJ. Folded-back solution structure of monomeric factor H of human complement by synchrotron X-ray and neutron scattering, analytical ultracentrifugation and constrained molecular modelling. J Mol Biol. 2001;309:1117–1138. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson JP, Goodship THJ. Complement factor H and the hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Exp Med. 2007;11:1245–1248. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird PN, Guida E, Chu DT, Vu HT, Guymer RH. The epsilon2 and epsilon4 alleles of the apolipoprotein gene are associated with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1311–1315. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird PN, Robman LD, Richardson AJ, Dimitrov PN, Tikellis G, McCarty CA, Guymer RH. Gene environment interaction in progression of AMD: the CFH gene, smoking and exposure to chronic infection. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1299–1305. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shabat S, Itagaki Y, Jockusch S, Sparrow JR, Turro NJ, Nakanishi K. Formation of a nona-oxirane from A2E, a lipofuscin fluorophore related to macular degeneration, and evidence of singlet oxygen involvement. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41 (5):814–817. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020301)41:5<814::aid-anie814>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boona CJF, van de Karb NC, Kleveringa BJ, Keunena JEE, Cremers FPM, Klaver CWC, Hoyng CB, Daha MR, den Hollander AI, Herrmann A. The spectrum of phenotypes caused by variants in the CFH gene. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:1573–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J, Nelson KC, Wu M, Sternberg P, Jones DP. Oxidative damage and protection of the RPE. Prog Ret Eye Res. 2000;19 (2):205–221. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(99)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano M, Fijalkowski N, Kondo N, Dike S, Handa J. Advanced glycation endproduct changes to Bruch’s membrane promotes lipoprotein retention by lipoprotein lipase. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:850–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell A, McGarvey DJ, Roberts J, Sarna T, Truscott TG. Photochemical studies of A2E. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2001;64:162–165. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charbel Issa P, Bolz HJ, Ebermann I, Domeier E, Holz FG, Scholl HP. Characterisation of severe rod-cone dystrophy in a consanguineous family with a splice site mutation in the MERTK gene. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:920–925. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.147397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Stambolian D, Edwards AO, Branham KE, Othman M, Jakobsdottir J, Tosakulwong N, Pericak-Vance MA, Campochiaro PA, Klein ML, Tan PL, Conley YP, Kanda A, Kopplin L, Li Y, Augustaitis KJ, Karoukis AJ, Scott WK, Agarwal A, Kovach JL, Schwartz SG, Postel EA, Brooks M, Baratz KH, Brown WL, Brucker AJ, Orlin A, Brown G, Ho A, Regillo C, Donoso L, Tian L, Kaderli B, Hadley D, Hagstrom SA, Peachey NS, Klein R, Klein BE, Gotoh N, Yamashiro K, Ferris F, III, Fagerness JA, Reynolds R, Farrer LA, Kim IK, Miller JW, Corton M, Carracedo A, Sanchez-Salorio M, Pugh EW, Doheny KF, Brion M, Deangelis MM, Weeks DE, Zack DJ, Chew EY, Heckenlively JR, Yoshimura N, Iyengar SK, Francis PJ, Katsanis N, Seddon JM, Haines JL, Gorin MB, Abecasis GR, Swaroop A. Genetic variants near TIMP3 and high-density lipoprotein-associated loci influence susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107 (16):7401–7406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912702107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani V, Matharu BK, Khan JC, Shahid H, Stanton CM, Hayward C, Wright AF, Bunce C, Clayton DG, Moore AT, Yates JR. Genetic variation in complement regulators and susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Immunobiology. 2012;217:158–161. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey PJ, Gias C, McDermott CJ, Lundh P, Pickering MC, Sethi C, Bird A, Fitzke FW, Maass A, Chen LL, Holder GE, Luthert PJ, Salt TE, Moss SE, Greenwood J. Complement factor H deficiency in aged mice causes retinal abnormalities and visual dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16651–16656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705079104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabb JW, Miyagi M, Gu X, Shadrach K, West KA, Sakaguchi H, Kamei M, Hasan A, Yan L, Raybourn ME, Salomon RG, Hollyfield JG. Drusen proteome analysis: an approach to the etiology of age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14682–14687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222551899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio CA, Johnson M, Rudolf M, Huang JD. The oil spill in ageing Bruch membrane. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:1638–1645. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dentchev T, Milam AH, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ, Dunaief JL. Amyloid-β is found in drusen from some age-related macular degeneration retinas, but not in drusen from normal retinas. Mol Vis. 2003;9:184–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon J, Wang Z, Avalle LB, Gaillard ER. The photochemical oxidation of A2E results in the formation of a 5,8,5′,8′-bis-furanoid oxide. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79 (4):537–542. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding JD, Johnson LV, Herrmann RK, Farsiu S, Smith SG, Groelle M, Mace BE, Sullivan P, Jamison JA, Kelly U, Harrabi O, Bollini SS, Dilley J, Kobayashi D, Kuang B, Li W, Pons J, Lin JC, Bowes Rickman C. Anti-amyloid therapy protects against retinal pigmented epithelium damage and vision loss in a model of age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:E279–E287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100901108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoso LA, Kim D, Frost A, Callahan A, Hageman G. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 2006;51:137–152. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AO, Ritter R, Abel KJ, Manning A, Panhuysen C, Farrer LA. Complement factor H polymorphism and age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:421–424. doi: 10.1126/science.1110189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerness JA, Maller JB, Neale BM, Reynolds RC, Daly MJ, Seddon JM. Variation near complement factor I is associated with risk of advanced AMD. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17 (1):100–104. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farboud B, Aotaki-Keen A, Miyata T, Hjelmeland LM, Handa JT. Development of a polyclonal antibody with broad epitope specificity for advanced glycation end products and localization of these epitopes in Bruch’s membrane of the aging eye. Mol Vis. 1999;5:11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara DC, Merriam JE, Freund KB, Spaide RF, Takahashi BS, Zhitomirsky I, Fine HF, Yannuzzi LA, Allikmets R. Analysis of major alleles associated with age-related macular degeneration in patients with multifocal choroiditis: strong association with complement factor H. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1562–1566. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.11.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher AE, Bentham GC, Agnew M, Young IS, Augood C, Chakravarthy U, de Jong PT, Rahu M, Seland J, Soubrane G, Tomazzoli L, Topouzis F, Vingerling JR, Vioque J. Sunlight exposure, antioxidants, and age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1396–1403. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.10.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard ER, Atherton SJ, Eldred G, Dillon J. Photophysical studies on human retinal lipofuscin. Photochem Photobiol. 1995;61:448–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1995.tb02343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard ER, Avalle LB, Keller LMM, Wang Z, Reszka KJ, Dillon JP. A mechanistic study of the photooxidation of A2E, a component of human retinal lipofuscin. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galor A, Lee DJ. Effects of smoking on ocular health. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22:477–482. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32834bbe7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannakis E, Jokiranta TS, Male DA, Ranganathan S, Ormsby RJ, Fischetti VA, Mold C, Gordon DL. A common site within factor H SCR 7 responsible for binding heparin, C-reactive protein and streptococcal M protein. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:962–969. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn JV, Beattie JR, Barrett L, Frizzell N, Thorpe SR, Boulton ME, McGarvey JJ, Stitt AW. Confocal raman microscopy can quantify advanced glycation end product (AGE) modification in Bruch’s membrane leading to accurate nondestructive prediction of ocular aging. FASEB J. 2007;21:3542–3552. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7896com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn JV, Mahaffy H, Dasari S, Oliver M, Chen M, Boulton ME, Xu H, Curry WJ, Stitt AW. Proteomic profiling of human retinal pigment epithelium exposed to an advanced glycation-modified substrate. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;250 (3):349–359. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1856-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold B, Merriam JE, Zernant J, Hancox LS, Taiber AJ, Gehrs K, Cramer K, Neel J, Bergeron J, Barile GR, Smith RT, Hageman GS, Dean M, Allikmets R AMD Genetics Clinical Study Group. Variation in factor B (BF) and complement component 2 (C2) genes is associated with age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet. 2006;38:458–462. doi: 10.1038/ng1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey AC, Crouch RK, Koutalos Y, Schey KL, Ablonczy Z. Spatial localization of A2E in the retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:3926–3933. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-7020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Pauer GJ, Yue X, Narendra U, Sturgill GM, Bena J, Gu X, Peachey NS, Salomon RG, Hagstrom SA, Crabb JW Group C.G.a.P.A.S. Assessing susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration with proteomic and genomic biomarkers. Mol Cell Proteomic. 2009;8:1338–1349. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800453-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hageman GS, Anderson DH, Johnson LV, Hancox LS, Taiber AJ, Hardisty LI, Hageman JL, Stockman HA, Borchardt JD, Gehrs KM, Smith RJH, Silvestri G, Russell SR, Klaver CCW, Barbazetto I, Chang S, Yannuzzi LA, Barile GR, Merriam JC, Smith RT, Olsh AK, Bergeron J, Zernant J, Merriam JE, Gold B, Dean M, Allikmets R. A common haplotype in the complement regulatory gene factor H (HF1/CFH) predisposes individuals to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7227–7232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501536102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hageman GS, Hancox LS, Taiber AJ, Gehrs KM, Anderson DH, Johnson LV, Radeke MJ, Kavanagh D, Richards A, Atkinson J, Meri S, Bergeron J, Zernant J, Merriam JC, Gold B, Allikmets R, Dean M. Extended haplotypes in the complement factor H (CFH) and CFH-related (CFHR) family of genes protect against age-related macular degeneration: characterization, ethnic distribution and evolutionary implications. Ann Med. 2006;38:592–604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hageman GS, Luthert PJ, Chong NHV, Johnson LV, Anderson DH, Mullins RF. An integrated hypothesis that considers drusen as biomarkers of immune-mediated processes at the RPE-Bruch’s membrane interface in aging and age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20 (6):705–732. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines JL, Hauser MA, Schmidt S, Scott WK, Olson LM, Gallins P, Spencer KL, Kwan SY, Noureddine M, Gilbert JR, Schnetz-Boutaud N, Agarwal A, Postel EA, Pericak-Vance MA. Complement factor H variant increases the risk of age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:419–421. doi: 10.1126/science.1110359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa JT, Reiser KM, Matsunaga H, Hjelmeland LM. The advanced glycation endproduct pentosidine induces the expression of PDGF-β in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 1998;66 (4):411–419. doi: 10.1006/exer.1997.0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa JT, Verzijl N, Matsunaga H, Aotaki-Keen A, Lutty GA, Koppele JM, Miyata T, Hjelmeland LM. Increase in advanced glycation end product pentosidine in Bruch’s membrane with age. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:775–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haralampus-Grynaviski NM, Lamb LE, Clancy CMR, Skumatz C, Burke JM, Sarna T, Simon JD. Spectroscopic and morphological studies of human retinal lipofuscin granules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100 (6):3179–3184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630280100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert AP, Deakin JA, Schmidt CQ, Blaum BS, Egan C, Ferreira VP, Pangburn MK, Lyon M, Uhrín D, Barlow PN. Structure shows that a glycosaminoglycan and protein recognition site in factor H is perturbed by age-related macular degeneration-linked single nucleotide polymorphism. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18960–18968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609636200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollyfield JG, Bonilha VL, Rayborn ME, Yang X, Shadrach KG, Lu L, Ufret RL, Salomon RG, Perez VL. Oxidative damage-induced inflammation initiates age-related macular degeneration. Nat Med. 2008;14:194–198. doi: 10.1038/nm1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AE, Orr N, Esfandiary H, Diaz-Torres M, Goodship T, Chakravarthy U. A common CFH haplotype, with deletion of CFHR1 and CFHR3, is associated with lower risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1173–1177. doi: 10.1038/ng1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter JJ, Morgan JI, Merigan WH, Sliney DH, Sparrow JR, Williams DR. The susceptibility of the retina to photochemical damage from visible light. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012;31:28–42. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi T, Murata T, Hangai M, Nagai R, Horiuchi S, Lopez PF, Hinton DR, Ryan SJ. Advanced glycation end products in age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:1629–1632. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.12.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida O, Oku H, Ikeda T, Nishimura M, Kawagoe K, Nakamura K. Is Chlamydia pneumoniae infection a risk factor for age related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:523–524. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.5.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang YP, Matsuda H, Itagaki Y, Nakanishi K, Sparrow JR. Characterization of peroxy-A2E and furan-A2E photooxidation products and detection in human and mouse retinal pigment epithelial cells lipofuscin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39732–39739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett SG, Lin H, Godley BF, Boulton ME. Mitochondrial DNA damage and its potential role in retinal degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2008;27:596–607. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LV, Leitner WP, Rivest AJ, Staples MK, Radeke MJ, Anderson DH. The Alzheimer’s Aβ-peptide is deposited at sites of complement activation in pathologic deposits associated with aging and age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99 (18):11830–11835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192203399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalayoglu MV, Galvan C, Mahdi OS, Byrne GI, Mansour S. Serological association between Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:478–482. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanofsky JR, Sima PD, Richter C. Singlet-oxygen generation from A2E. Photochem Photobiol. 2003;77 (3):235–242. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2003)077<0235:sogfa>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunadharma PP, Nordgaard CL, Olsen TW, Ferrington DA. Mitochondrial DNA damage as a potential mechanism for age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:5470–5479. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandhadia S, Foster S, Cree A, Griffiths H, Osmond C, Goverdhan S, Lotery A. Chlamydia infection status, genotype, and age-related macular degeneration. Mol Vis. 2012;18:29–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandhadia S, Lotery A. Oxidation and age-related macular degeneration: insights from molecular biology. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2010;12:e34. doi: 10.1017/S146239941000164X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SR, Jang YP, Jockusch S, Fishkin NE, Turro NJ, Sparrow JR. The all-trans-retinal dimer series of lipofuscin pigments in retinal pigment epithelial cells in a recessive Stargardt disease model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19273–19278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708714104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YH, He S, Kase S, Kitamura M, Ryan SJ, Hinton DR. Regulated secretion of complement factor H by RPE and its role in RPE migration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:651–659. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1049-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkitadze MD, Barlow PN. Structure and flexibility of the multiple domain proteins that regulate complement activation. Immunol Rev. 2001;180:146–161. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1800113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RJ, Zeiss C, Chew EY, Tsai JY, Sackler RS, Haynes C, Henning AK, SanGiovanni JP, Mane SM, Mayne ST, Bracken MB, Ferris FL, Ott J, Barnstable C, Hoh J. Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:385–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1109557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnadev N, Meleth AD, Chew EY. Nutritional supplements for age-related macular degeneration. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21:184–189. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32833866ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurji KH, Cui JZ, Lin T, Harriman D, Prasad SS, Kojic L, Matsubara JA. Microarray analysis identifies changes in inflammatory gene expression in response to amyloid-beta stimulation of cultured human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1151–1163. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine M, Jarva H, Seitsonen S, Haapasalo K, Lehtinen MJ, Lindeman N, Anderson DH, Johnson PT, Jarvela I, Jokiranta TS, Hageman GS, Immonen I, Meri S. Y402H polymorphism of complement factor H affects binding affinity to C-reactive protein. J Immunol. 2007;178:3831–3836. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb LE, Ye T, Haralampus-Grynaviski NM, Williams TR, Pawlak A, Sarna T, Simon JD. Primary photophysical properties of A2E in solution. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:11507–11512. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod DS, Grebe R, Bhutto I, Merges C, Baba T, Lutty GA. Relationship between RPE and choriocapillaris in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:4982–4991. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JI, Dubra A, Wolfe R, Merigan WH, Williams DR. In vivo autofluorescence imaging of the human and macaque retinal pigment epithelial cell mosaic. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1350–1359. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale BM, Fagerness J, Reynolds R, Sobrin L, Parker M, Raychaudhuri S, Tan PL, Oh EC, Merriam JE, Souied E, Bernstein PS, Li B, Frederick JM, Zhang K, Brantley MAJ, Lee AY, Zack DJ, Campochiaro B, Campochiaro P, Ripke S, Smith RT, Barile GR, Katsanis N, Allikmets R, Daly MJ, Seddon JM. Genome-wide association study of advanced age-related macular degeneration identifies a role of the hepatic lipase gene (LIPC) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7395–7400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912019107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsome DA, Miceli MV, Liles MR, Tate DJ, Oliver PD. Antioxidants in the retinal pigment epithelium. Prog Ret Eye Res. 1994;13:101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki M, Raisler BJ, Sakurai E, Sarma JV, Barnum SR, Lambris JD, Chen Y, Zhang K, Ambati BK, Baffi JZ, Ambati J. Drusen complement components C3a and C5a promote choroidal neovascularization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2328–2333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408835103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno-Matsui K. Parallel findings in age-related macular degeneration and Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Ret Eye Res. 2011;30:217–238. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormsby RJ, Ranganathan S, Tong JC, Griggs KM, Dimasi DP, Hewitt AW, Burdon KP, Craig JE, Hoh J, Gordon DL. Functional and structural implications of the complement factor H Y402H polymorphism associated with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:1763–1770. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak A, Wrona M, Rozanowska M, Zareba M, Lamb LE, Roberts JE, Simon JD, Sarna T. Comparison of the aerobic photoreactivity of A2E with its precursor retinal. Photochem Photobiol. 2003;77:253–258. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2003)077<0253:cotapo>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins SJ, Nan R, Okemefuna AI, Li K, Khan S, Miller A. Multiple interactions of complement factor H with its ligands in solution: a progress report. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;703:25–47. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5635-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proitsi P, Lupton MK, Dudbridge F, Tsolaki M, Hamilton G, Daniilidou M, Pritchard M, Lord K, Martin BM, Craig D, Todd S, McGuinness B, Hollingworth P, Harold D, Kloszewska I, Soininen H, Mecocci P, Velas B, Gill M, Lawlor B, Rubinsztein DC, Brayne C, Passmore PA, Williams J, Lovestone S, Powell JF. Alzheimer’s disease and age-related macular degeneration have different genetic models for complement gene variation. Neurobiol Aging. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.12.036. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani N, Thornalley PJ. The dicarbonyl proteome. Proteins susceptible to dicarbonyl glycation at functional sites in health, aging and disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1126:124–127. doi: 10.1196/annals.1433.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radu RA, Hu J, Yuan Q, Welch DL, Makshanoff J, Lloyd M, McMullen S, Travis GH, Bok D. Complement system dysregulation and inflammation in the retinal pigment epithelium of a mouse model for Stargardt macular degeneration. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:18593–18601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.191866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radu RA, Mata NL, Bagla A, Travis GH. Light exposure stimulates formation of A2E oxiranes in a mouse model of Stargardt’s macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101 (16):5928–5933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308302101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragauskaite L, Heckathorn RC, Gaillard ER. Environmental effects on the photochemistry of A2E, a component of human retinal lipofuscin. Photochem Photobiol. 2001;74 (3):483–488. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2001)074<0483:eeotpo>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raychaudhuri S, Iartchouk O, Chin K, Tan P, Tai A, Ripke S, Gowrisankar S, Vemuri S, Montgomery K, Yu Y, Reynolds R, Zack DJ, Campochiaro B, Campochiaro P, Katsanis N, Daly MJ, Seddon JM. A rare penetrant mutation in CFH confers high risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1232–1236. doi: 10.1038/ng.976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reszka K, Eldred GE, Wang RH, Chignell C, Dillon J. The photochemistry of human retinal lipofuscin as studied by EPR. Photochem Photobiol. 1995;62 (6):1005–1008. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1995.tb02400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera A, Fisher SA, Fritsche LG, Keilhauer CN, Lichtner P, Meitinger T, Weber BH. Hypothetical LOC387715 is a second major susceptibility gene for age-related macular degeneration, contributing independently of complement factor H to disease risk. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14 (21):3227–3236. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Kukielczak BM, Hu DN, Miller DS, Bilski P, Sik RH, Motten AG, Chignell CF. The role of A2E in prevention or enhancement of light damage in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Photochem Photobiol. 2002;75 (2):184–190. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2002)075<0184:troaip>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robman L, Mahdi O, McCarty C, Dimitrov P, Tikellis G, McNeil J, Byrne G, Taylor H, Guymer RH. Exposure to Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and progression of age-related macular degeneration. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:1013–1019. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez IR, Larrayoz IM. Cholesterol oxidation in the retina: implications of 7KCh formation in chronic inflammation and age-related macular degeneration. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:2847–2862. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R004820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozanowska M, Jarvis-Evans J, Korytowski W, Boulton ME, Burke JM, Sarna T. Blue light-induced reactivity of retinal age pigment. In vitro generation of oxygen-reactive species. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18825–18830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozanowska M, Wessels J, Boulton M, Burke JM, Rodgers MAJ, Truscott TG, Sarna T. Blue light-induced singlet oxygen generation by retinal lipofuscin in non-polar media. Free Rad Biol Med. 1998;24:1107–1112. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00395-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu E, Fridley BL, Tosakulwong N, Bailey KR, Edwards AO. Genome-wide association analyses of genetic, phenotypic, and environmental risks in the age-related eye disease study. Mol Vis. 2010;16:2811–2821. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarks JP, Sarks SH, Killingsworth MC. Evolution of geographic atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. Eye. 1988;2:552–577. doi: 10.1038/eye.1988.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl HPN, Issa PC, Walier M, Janzer S, Pollok-Kopp B, Börncke F, Fritsche LG, Chong NV, Fimmers R, Wienker T, Holz FG, Weber BHF, Oppermann M. Systemic complement activation in age-related macular degeneration. Plos one. 2008;3:e2593. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutt F, Davies S, Kopitz J, Holz FG, Boulton ME. Photodamage to human RPE cells by A2-E, a retinoid component of lipofuscin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41 (8):2303–2308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon JM, Ajani UA, Sperduto RD, Hiller R, Blair N, Burton TC, Farber MD, Gragoudas ES, Haller J, Miller DTea. Dietary carotenoids, vitamins A, C and E and advanced age-related macular degeneration Eye disease case-control study group. JAMA. 1994;272 (18):1413–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon JM, Gensler G, Rosner B. C-reactive protein and CFH, ARMS2/HTRA1 gene variants are independently associated with risk of macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1560–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon JM, Santangelo SL, Book K, Chong S, Cote J. A genomewide scan for age-related macular degeneration provides evidence for linkage to several chromosomal regions. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:780–790. doi: 10.1086/378505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjoberg AP, Trouw LA, Clark S, Sjolander J, Heinegard D, Sim RB, Day AJ, Blom AM. The factor H variant associated with age-related macular degeneration (His-384) and the non-disease-associated form bind differentially to C-reactive protein, fibromodulin, DNA, and necrotic cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282 (15):10894–108900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofat R, Casas JP, Webster AR, Bird AC, Mann SS, Yates JR, Moore AT, Sepp T, Cipriani V, Bunce C, Khan JC, Shahid H, Swaroop A, Abecasis G, Branham KE, Zareparsi S, Bergen AA, Klaver CC, Baas DC, Zhang K, Chen Y, Gibbs D, Weber BH, Keilhauer CN, Fritsche LG, Lotery A, Cree AJ, Griffiths HL, Bhattacharya SS, Chen LL, Jenkins SA, Peto T, Lathrop M, Leveillard T, Gorin MB, Weeks DE, Ortube MC, Ferrell RE, Jakobsdottir J, Conley YP, Rahu M, Seland JH, Soubrane G, Topouzis F, Vioque J, Tomazzoli L, Young I, Whittaker J, Chakravarthy U, de Jong PT, Smeeth L, Fletcher A, Hingorani AD. Complement factor H genetic variant and age-related macular degeneration: effect size, modifiers and relationship to disease subtype. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41 (1):250–262. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow JR, Gregory-Roberts E, Yamamoto K, Blonska A, Ghosh SK, Ueda K, Zhou J. The bisretinoids of retinal pigment epithelium. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2011;31:121–135. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow JR, Nakanishi K, Parish CA. The lipofuscin fluorophore A2E mediates blue light-induced damage to retinal pigmented epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41 (7):1981–1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow JR, Zhou J, Ben-Shabat S, Vollmer H, Itagaki Y, Nakanishi K. Involvement of oxidative mechanisms in blue light induced damage to A2E-laden RPE. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43 (4):1222–1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaroop A, Chew EY, Rickman CB, Abecasis GR. Unraveling a multifactorial late-onset disease: from genetic susceptibility to disease mechanisms for age-related macular degeneration. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:19–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurman JM, Renner B, Kunchithapautham K, Ferreira VP, Pangburn MK, Ablonczy Z, Tomlinson S, Holers VM, Rohrer B. Oxidative stress renders retinal pigment epithelial cells susceptible to complement-mediated injury. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16939–16947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808166200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J, Ishibashi K, Ishibashi K, Reiser K, Grebe R, Biswal S, Gehlbach P, Handa JT. Advanced glycation endproduct-induced aging of the retinal pigment epithelium and choroid: a comprehensive transcriptional response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11846–11851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504759102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troutbeck R, Al-Qureshi S, Guymer RH. Therapeutic targeting of the complement system in age-related macular degeneration: a review. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2012;40:18–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2011.02581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ufret-Vincenty RL, Aredo B, Liu X, McMahon A, Chen PW, Sun H, Niederkorn JY, Kedzierski W. Transgenic mice expressing variants of complement factor H develop AMD-like retinal findings. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:5878–5887. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Ohno-Matsui K, Yoshida T, Shimada N, Ichinose S, Sato T, Mochizuki M, Morita I. Amyloid-beta up-regulates complement factor B in retinal pigment epithelial cells through cytokines released from recruited macrophages/microglia: another mechanism of complement activation in age-related macular degeneration. J Cell Physiol. 2009;220:119–128. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Keller LMM, Dillon J, Gaillard ER. Oxidation of A2E results in the formation of highly reactive aldehydes and ketones. Photochem Photobiol. 2006;82:1251–1257. doi: 10.1562/2006-04-01-RA-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks DE, Conley YP, Tsai HJ, Mah TS, Schmidt S, Postel EA, Agarwal A, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Rosenfeld PJ, Paul TO, Eller AW, Morse LS, Dailey JP, Ferrell RE, Gorin MB. Age-related maculopathy: a genomewide scan with continued evidence of susceptibility loci within the 1q31, 10q26, and 17q25 regions. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:174–189. doi: 10.1086/422476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weismann D, Hartvigsen K, Lauer N, Bennett KL, Scholl HP, Charbel IP, Cano M, Brandstätter H, Tsimikas S, Skerka C, Superti-Furga G, Handa JT, Zipfel PF, Witztum JL, Binder CJ. Complement factor H binds malondialdehyde epitopes and protects from oxidative stress. Nature. 2011;478:76–81. doi: 10.1038/nature10449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Yanase E, Feng X, Siegel MM, Sparrow JR. Structural characterization of bisretinoid A2E photocleavage products and implications for age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:7275–7280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913112107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Lauer TW, Sick A, Hackett SF, Campochiaro PA. Oxidative stress modulates complement factor H expression in retinal pigmented epithelial cells by acetylation of FOXO3. J Biol Chem. 2007;282 (31):22414–22425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y, Ishibashi K, Ishibashi K, Bhutto IA, Tian J, Lutty GA, Handa JT. The expression of advanced glycation endproduct receptors in rpe cells associated with basal deposits in human maculas. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:840–848. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates JR, Sepp T, Matharu BK, Khan JC, Thurlby DA, Shahid H, Clayton DG, Hayward C, Morgan J, Wright AF, Armbrecht AM, Dhillon B, Deary IJ, Redmond E, Bird AC, Moore AT. Complement C3 variant and the risk of age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2007;357 (6):553–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarbin MA, Rosenfeld PJ. Pathway-based therapies for age-related macular degeneration. An integrated survey of emerging treatment alternatives. Retina. 2010;30:1350–1367. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181f57e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Cai B, Jang YP, Pachydaki S, Schmidt AM, Sparrow JR. Mechanisms for the induction of HNE- MDA- and AGE-adducts, RAGE and VEGF in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80:567–580. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Jang YP, Kim SR, Sparrow JR. Complement activation by photooxidation products of A2E, a lipofuscin constituent of the retinal pigment epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16182–16187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604255103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Kim SR, Westlund BS, Sparrow JR. Complement activation by bisretinoid constituents of RPE lipofuscin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1392–1399. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel PF, Skerka C. Complement regulators and inhibitory proteins. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:729–740. doi: 10.1038/nri2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]