Abstract

The abnormal production and accumulation of β-amyloid peptide (Aβ), which is produced from amyloid precursor protein (APP) by the sequential actions of β-secretase and γ-secretase, are thought to be the initial causative events in the development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Accumulating evidence suggests that vascular factors play an important role in the pathogenesis of AD. Specifically, studies have suggested that one vascular factor in particular, oxidized low density lipoprotein (oxLDL), may play an important role in regulating Aβ formation in AD. However, the mechanism by which oxLDL modulates Aβ formation remains elusive. In this study, we report several new findings that provide biochemical evidence suggesting that the cardiovascular risk factor oxLDL may contribute to Alzheimer’s disease by increasing Aβ production. First, we found that lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), the most bioactive component of oxLDL induces increased production of Aβ. Second, our data strongly indicate that LPA induces increased Aβ production via upregulating β-secretase expression. Third, our data strongly support the notion that different isoforms of protein kinase C (PKC) may play different roles in regulating APP processing. Specifically, most PKC members, such as PKCα, PKCβ, and PKCε, are implicated in regulating α-secretase-mediated APP processing; however, PKCδ, a member of the novel PKC subfamily, is involved in LPA-induced upregulation of β-secretase expression and Aβ production. These findings may contribute to a better understanding of the mechanisms by which the cardiovascular risk factor oxLDL is involved in Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Lysophosphatidic acid, Oxidized LDL, β-secretase, Beta-amyloid peptide, Amyloid precursor protein

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized clinically by progressive dementia, including loss of learning and memory. Pathologically, it is characterized by degeneration of neurons and abnormal protein structures, including intracellular deposition of neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) that are composed of the microtubule-associated protein TAU, and extracellular deposits of various types of β amyloid (Aβ), which is a mix of peptides that are 39 to 43 amino acids in length. Several lines of evidence support the hypothesis that progressive accumulation of Aβ is an early and critical event in the pathogenesis of AD [1]. Studies have revealed that the accumulation of Aβ initiates a series of downstream neurotoxic events, including synaptic failure [2] and hyperphosphorylation of TAU, which results in neuronal dysfunction and death [3]. Aβ is proteolytically derived from a large amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β-secretase, which produces the N-terminus of Aβ, and γ-secretase, which produces the C-terminus of Aβ [4]. Thus, it is clear that β- and γ-secretases are the key enzymes in the production of Aβ. Augmented expression of any of these two secretases or APP itself would result in increased production of Aβ. β-secretase (also known as β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1 [BACE1]) has been identified as a type I membrane aspartyl protease [5–8]. γ-cleavage is a complex composed of at least four subunits, namely, presenilin (PS1 or PS2), nicastrin, Aph-1, and Pen-2, of which presenilin may be the putative catalytic subunit [9].

Recent progress in AD etiology studies suggests that vascular factors also play an important role in the pathogenesis of AD [10–12]. Specifically, it has been reported that one vascular factor in particular, oxidized low density lipoprotein (oxLDL), may play an important role in neuronal cell death in AD [13]. In this regard, postmortem analyses revealed that the overall level of oxidative damage to proteins and lipids is elevated in AD [10, 14], and specifically, cerebrospinal fluid lipoproteins are more vulnerable to oxidation in AD and are neurotoxic when oxidized [15]. In this regard, it is also notable that a recent study revealed a positive correlation between the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of Aβ and oxLDL in AD patients, suggesting that oxLDL may contribute to AD by manipulating Aβ production [16]. Studies have further shown that lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), the major bioactive component of oxLDL, can disrupt blood-brain barrier function and cause AD-related cellular events; for review, see [17]. Interestingly, in an effort to study the pathogenetic effect of this bioactive component of oxLDL, we found that LPA can enhance Aβ production in a cultured cell system. Furthermore, our data also demonstrate that LPA induces increased expression of β-secretase (BACE1), suggesting that LPA causes an increase in Aβ production by up-regulating β-secretase expression. This hypothesis is further supported by our finding that LPA induces the activation of the MAPK signaling pathway, which is known to mediate HNE- and LPA-induced gene expression [18, 19]. In addition, we also found that LPA markedly induces activation (phosphorylation) of the transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and induces CREB binding activity. Notably, CREB is one of the possible transcription regulators of the BACE1 gene [20]. Thus, our novel finding that components of oxLDL cause increased production of Aβ opens a new avenue of investigation into the mechanisms by which oxLDL contributes to the development of AD.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. General reagents

Aβ40 and Aβ42 were purchased from American Peptide (Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Monoclonal antibody 6E10 against Aβ and polyclonal antibodies against Aph1α and Pen- 2 were purchased from COVANCE (Dedham, MA, USA). Polyclonal antibody anti-nicastrin (NCT) was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Polyclonal antibodies Anti-PS1N raised against residues 27–50 of PS1 and C15 raised against the C-terminal 15 residues of human APP have been described previously [21, 22]. The polyclonal antibodies against phospho-MEK, phospho-ERK, phospho-p90RSK, phospho-CREB, phospho-ATF2, phospho-PKCα (Ser657), and phospho-PKCδ (Tyr311) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Polyclonal antibodies against proteins of PKCα and PKCδ and monoclonal antibody against β-actin were from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Anti-BACE1 antibody was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). LPA (1-oleoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero- 3-phosphate) was from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). Pertussis toxin (PTX), U0126, and GF109203X were from Biomol International (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA). Protein-A agarose beads and ECL-Plus Western blotting reagents were purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Phosphate buffer was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). TRIzol reagent was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). dCTP-32P was from MP Biochemicals (Solon, OH, USA), and DNA labeling kit was from GE Health Care (Piscataway, NJ, USA).

2.2. Cell culture and treatment

The mouse neuroblastoma N2a cell line (WT-7) stably expressing wild type presenilin 1 (PS1wt) and Swedish mutant APP (APPsw) were kindly provided by Drs. Sangram S. Sisodia and Seong-Hun Kim (University of Chicago) and were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin, and 1% L-glutamine as described previously [23]. For treatment with LPA, cells were starved for 24 h in serum-free DMEM and then treated with LPA in fresh serum-free medium at different concentrations or for a different length of time as indicated in the each related experiment. Cells were treated with PTX overnight and kinase inhibitors for 30 min prior to addition of LPA to examine their effects on the LPA-induced response.

2.3. Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis were carried out as described previously [21]. Secreted Aβ was immunoprecipitated from conditioned medium (CM) using a monoclonal Aβ-specific antibody 6E10 and Protein A beads. The immunoprecipitated Aβ peptides were analyzed by 13% urea (8M) SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting using 6E10. For detection of other proteins, cells were lysed in Western blotting lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, 8 M urea, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, and protease inhibitor) and separated by Tris-glycine SDS-PAGE. After being transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), the blots were probed with specific antibodies, and the immunoreactive bands were visualized using the ECL-Plus reagent.

2.4. Northern blot analysis

Total RNA of the cells was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and subjected to electrophoresis in formaldehyde-agarose gels. RNA was transferred onto nylon membranes (Amersham Biosciences) and hybridized with radiolabeled cDNA probes as described previously [24]. A [α-32P]dCTP-labeled 685-bp fragment of mouse BACE1 cDNA was used as a probe to detect mouse BACE mRNA.

2.5. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

Oligonucleotides AGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCAATGAAGGGGT, AACGGGCCGGGGGGTGGTGGCACACGCCTT, GGTGTTAACCAATGCTGATTCAGGAAAGTG, and TGCACTGGCTCCTGCTATGGGTGGGCTCGG containing the putative CRE, Sp-1, AP-1, and SRE sites of the mouse BACE1 promoter, respectively, were radiolabeled using [γ-32P] dCTP. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed as described previously [24]. All results presented in this study are representative of at least three experiments.

2.6. Data analysis

All Western blots shown are representative of a minimum of three independent experiments. For statistical analysis, the density of each band was quantified using the Gel Digitizing Software UN-SCAN-IT (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT, USA). The ratios of protein levels between treated samples and controls are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3. Comparisons between multiple groups were performed by using a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett posthoc t tests. A single comparison analysis was made using two-tailed unpaired Student t tests. For ANOVA or t tests, p values of ≤ 0.05 or ≤0.01 were considered to be statistically significant. Single and double asterisks indicate significant differences between control and treatment at p<0.05 and 0.01, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. LPA, a bioactive component of oxLDL, induced an increase in Aβ production

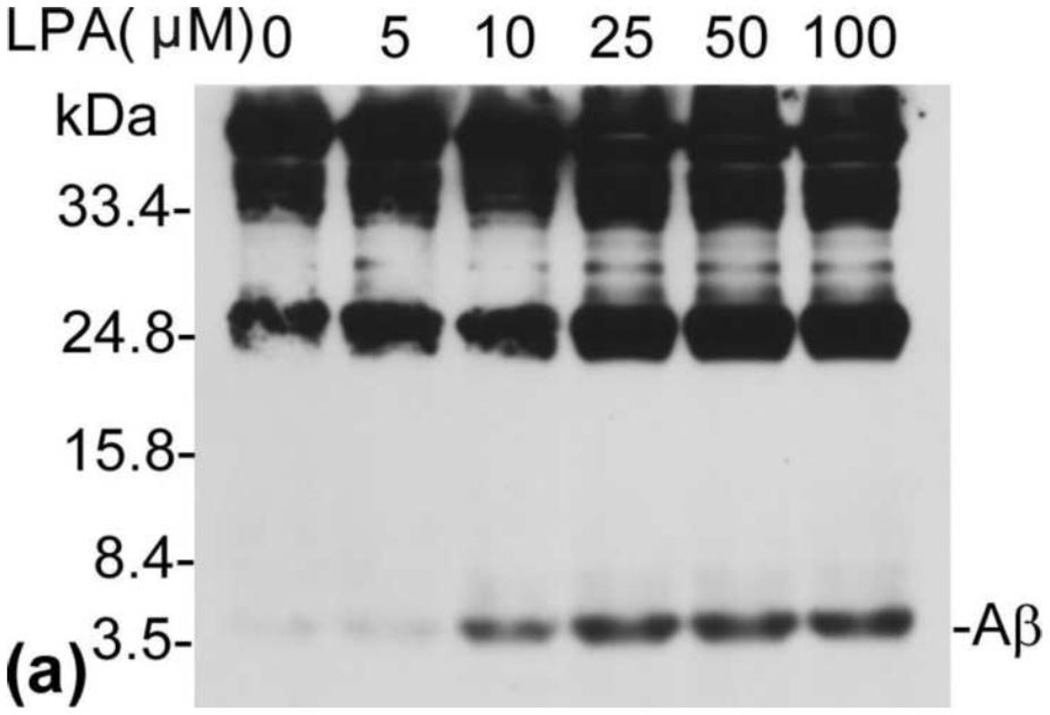

A recent study has shown a positive correlation between CSF levels of Aβ and oxLDL in AD patients, suggesting oxLDL may have effect on Aβ production [16]. Studies have further shown that LPA, the major bioactive component of oxLDL, can disrupt blood-brain barrier function and cause AD-related cellular events [17]. These observations prompted us to determine the effect of LPA on the production of Aβ. N2a neuroblastoma cells, which stably express PS1wt and myc-tagged APPsw, have been used in many previous studies for investigating the mechanism of Aβ production [21, 23, 25]. These cells were starved in a serum-free medium for 24 h and then treated with LPA. The secreted Aβ was immunoprecipitated from CM with 6E10 (COVANCE), a monoclonal antibody that recognizes residues 1–17 of Aβ [26], and analyzed by urea (8M) SDS-PAGE (13%) followed by Western blot using 6E10. As shown in Fig. 1, LPA remarkably induced Aβ production in a dose-dependent manner (top panel), and a peak level of Aβ was reached at 25 µM LPA.

Fig. 1.

LPA induces a dose-dependent increase in Aβ formation. (a) N2a cells were starved in serum-free medium containing 0.5% serum for 24 h and then treated with LPA at various concentrations as indicated. Secreted Aβ was immunoprecipitated from CM with 6E10 and analyzed by urea (8M) SDS-PAGE (13%) followed by Western blot using antibody 6E10. All Western blot data presented in this study are representative of the results obtained from at least three repeated experiments. (b) Quantitative analysis of Western blotting signals of secreted Aβ shown in (a). ANOVA identified a significant induction in secreted Aβ in dose curve experiment. **p≤0.01 vs. untreated control.

3.2. LPA upregulated β-secretase expression, but had no effect on the protein levels of APP and γ-secretase

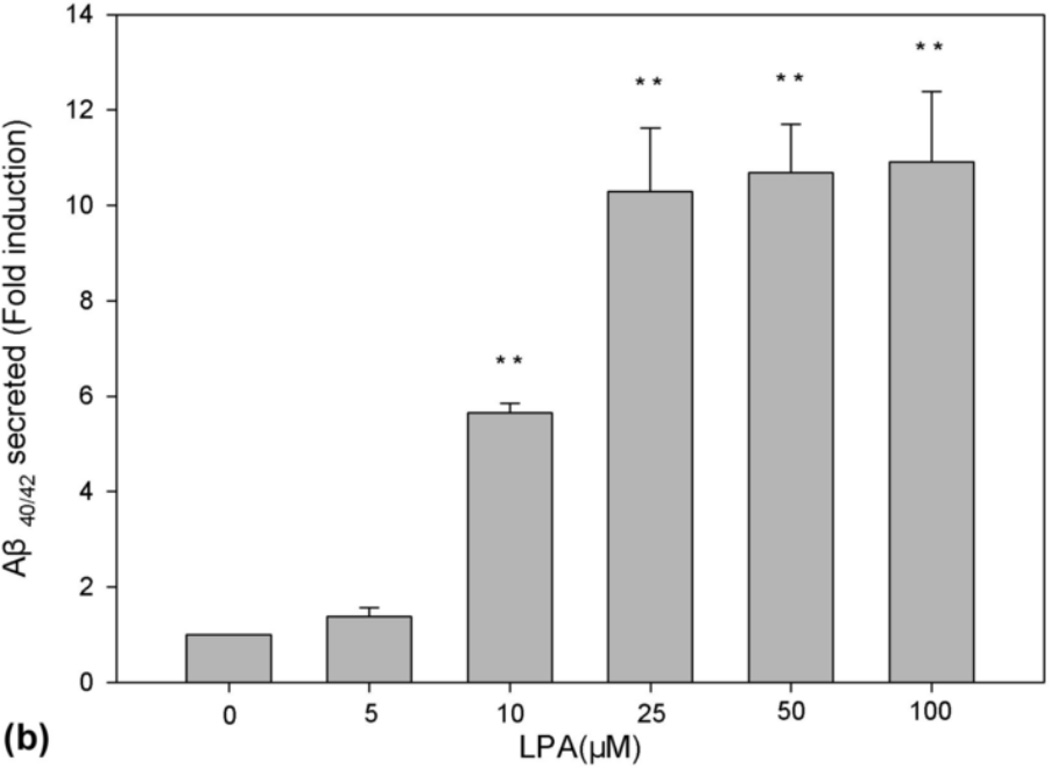

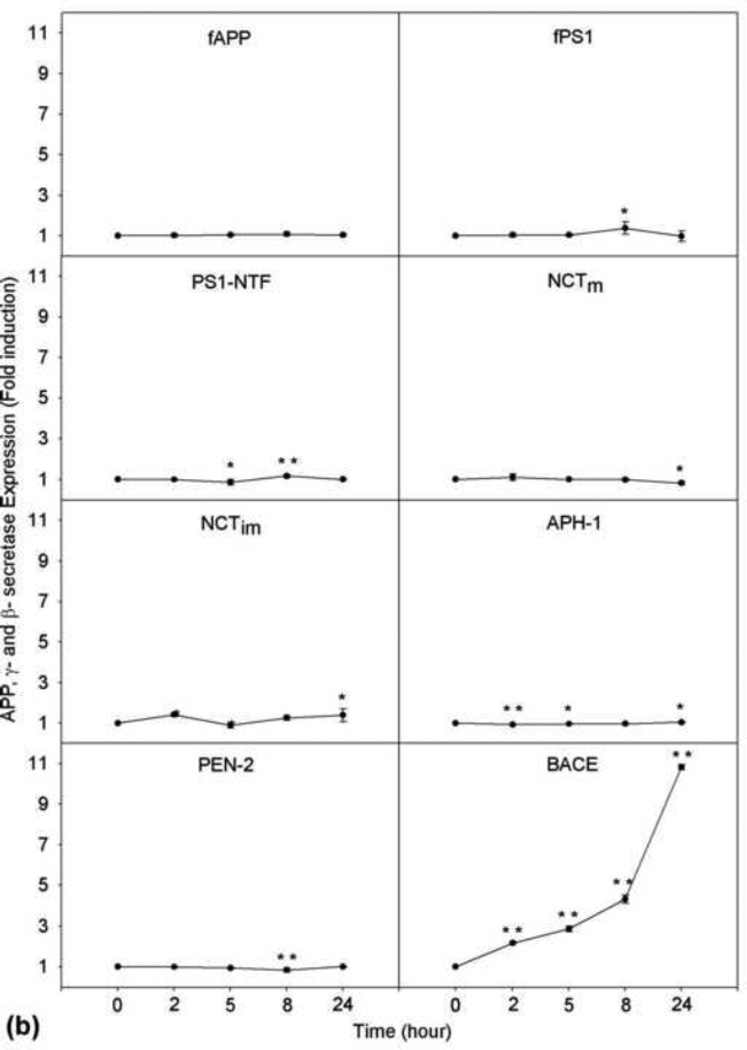

Since Aβ is produced from its large precursor APP by the sequential actions of β-secretase and γ-secretase, enhanced expression of any of these proteins may lead to increased production of Aβ. Thus, next, we determined whether treatment with LPA has any effect on the expression level of APP, β-secretase, and γ-secretase. As shown in Fig. 2a, when the cells were treated with 25 µM of LPA, which was shown to induce significant increases in Aβ (Fig. 1), LPA was found to have no effect on APP expression level in a time course up 24 h (top panel). When these samples were analyzed for the expression levels of the four components of γ-secretase (PS1, NCT, Aph-1α, and PEN-2), as shown in the second to sixth panels, none of these proteins’ levels was altered upon treatment with LPA. However, when these samples were analyzed for β-secretase (BACE1), a time-dependent and statistically significant increase in BACE1 protein level was observed (bottom panel of [a] and bottom panel, right column of [b]). This result strongly suggests that the LPA-induced increase in Aβ formation is mediated by upregulating β-secretase expression.

Fig. 2.

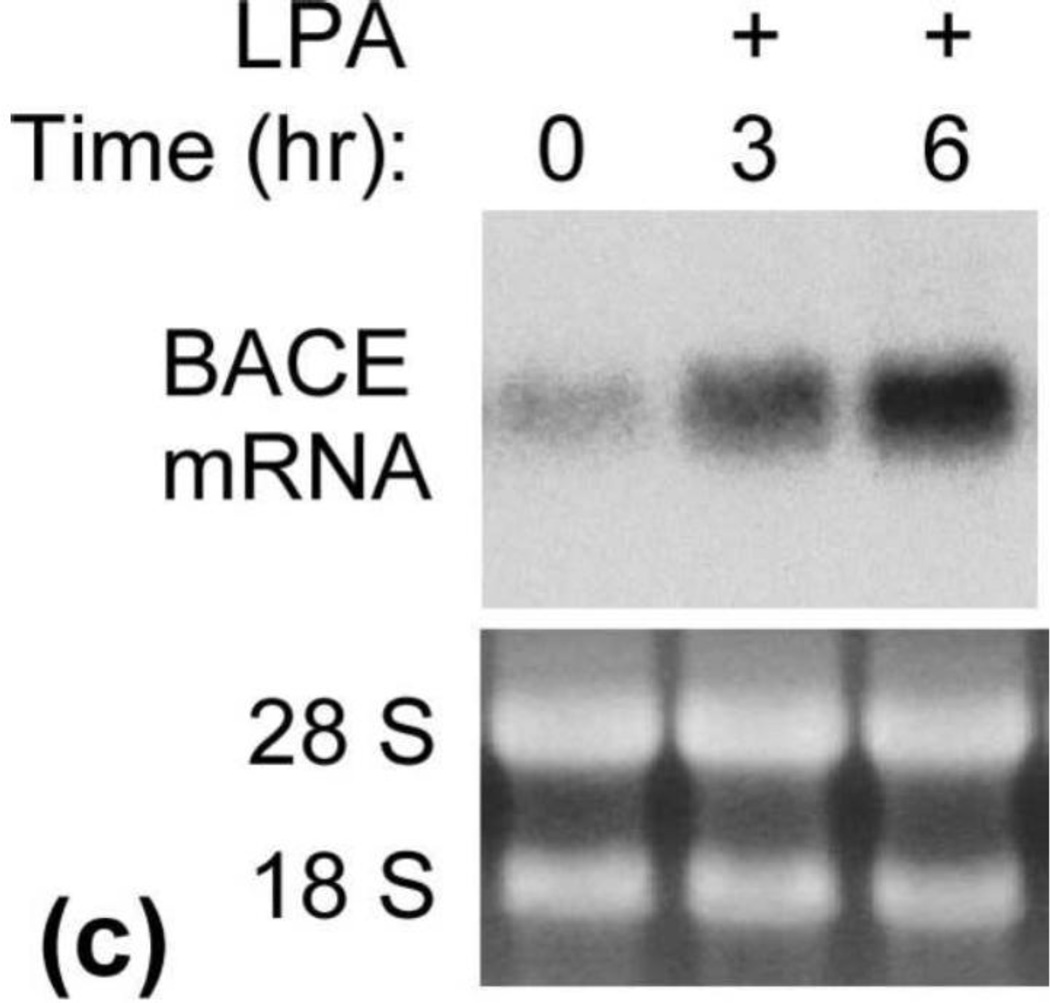

LPA induces increased expression of β-secretase protein. (a) Starved cells were treated with 25 µM LPA for different lengths of time as indicated. Cell lysates collected at each time point were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting assay. Top panel was probed with C15 raised against the C-terminal 15 amino acids to determine the level of full-length APP. Second panel is a blot probed with anti-PS1N to determine the expression level of PS1. Third, fourth, and fifth panels are blots probed with anti-NCT, anti-Aph-1α, and anti-Pen-2 antibodies, respectively, to determine the expression levels of these proteins. The bottom panel is the blot probed with anti-BACE1 antibody to determine the expression level of β-secretase. NCTm and NCTim indicate the mature and immature forms of Nicastrin. (b) Quantitative analysis of Western blotting signals shown in (a) identified a significant induction of BACE1 but not of components of γ-secretase or APP. *p≤0.05; **p≤0.01 vs. untreated control. (c) LPA induction of BACE1 mRNA. Starved cells were treated with 25 μM LPA. At the time points indicated, total RNA was isolated, and Northern blot analysis was performed using mouse BACE1 cDNA as a probe as described in our previous study [19]. Visualized bands of 28S and 18S ribosomal RNA served as loading controls.

3.3. LPA induced an increase in BACE1 mRNA

Next, we determined whether LPA upregulates BACE1 gene expression. To do so, starved cells were treated with 25 µM LPA, and the level of BACE1 mRNA was analyzed by Northern blot assay. As shown in Fig. 2c, LPA induced a time-dependent increase in BACE1 mRNA (top panel). The peak of BACE1 mRNA was observed at the time point of 6 h. The bottom panel shows the levels of 18S and 28S RNA as loading controls. This data suggest that LPA upregulates BACE1 expression at the transcriptional level by increasing the expression level of BACE1 mRNA.

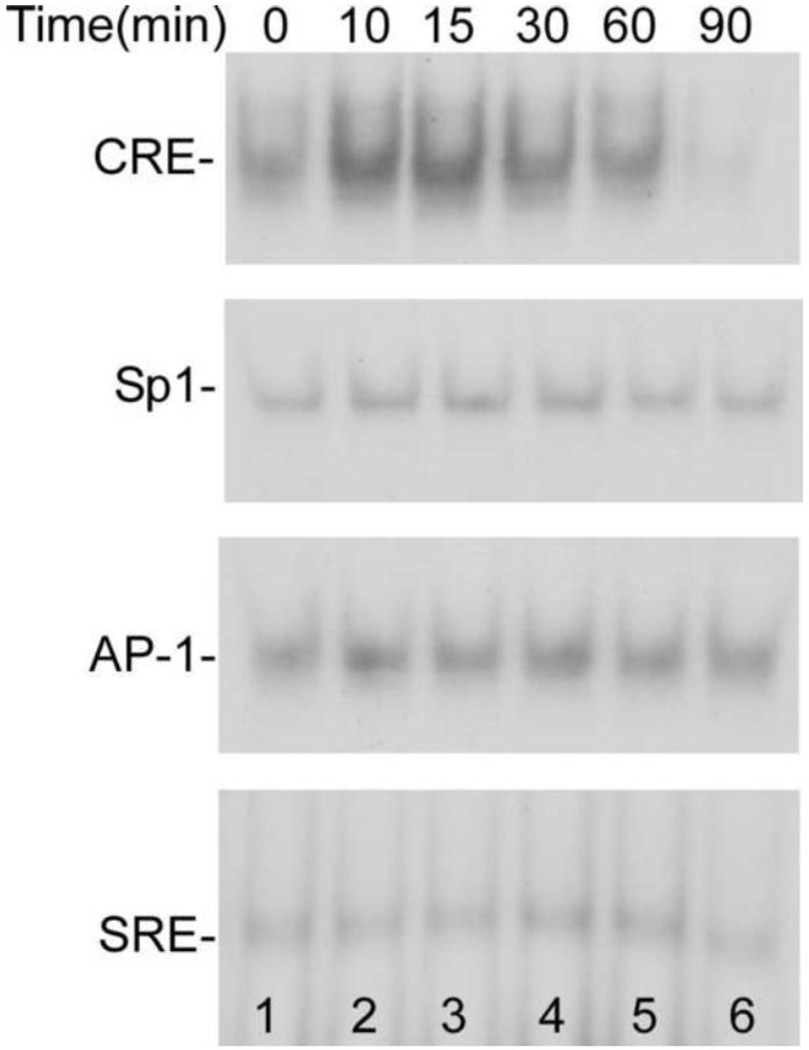

3.4. LPA induced increased binding activity of the transcription factor CREB, but not Sp1, AP-1, and SRF

Sequence analysis revealed that in the promoter region of the BACE1 gene, there are one cAMP responsive element (CRE), one Sp1 site, and several other transcription factors binding sites, such as AP-1, AP-2, AP-3, and SRE (serum response element) [27]. To examine whether these transcription factors play a role in mediating LPA-induced BACE1 gene expression, we determined the effect of LPA on the binding activity of these transcription factors to the BACE1 promoter by EMSA as described in our previous study [28]. Nuclear proteins from cells untreated (0) or treated with 25 μM LPA for indicated times were incubated with radiolabeled oligonucleotides which contain one of the following possible transcription factor binding sites: CRE site, Sp1 site, Ap-1 site, and SRE site of the BACE1 promoter for 20 min before loading onto a 6% TBE acrylamide gel. Interestingly, as shown in Fig. 3, we observed that the binding activity of CREB to the CRE site of the BACE1 promoter was significantly increased upon LPA stimulation (top panel). In contrast, the binding activities of Sp1 (second panel), AP-1 (third panel), and SRE (fourth panel) were not significantly changed. These results suggest that the transcription factor CREB mediates BACE1 regulation in response to LPA.

Fig. 3.

Time course of LPA-induced increase in binding activity of transcriptional factor CREB. LPA-induced binding activities of various transcription factors were analyzed by EMSA. Nuclear proteins from cells untreated (0) or treated with 25 μM LPA for indicated times were incubated with radiolabeled oligonucleotides that contain one of the following possible transcription factor binding sites of BACE1 promoter for 20 min: CRE site (top panel), Sp1 site (second panel), Ap-1 site (third panel), and SRE site (bottom panel). Then, proteins were separated by a 6% TBE acrylamide gel. The protein-nucleic acid complexes were determined by autoradiography of 32P-labeled nucleic acid.

3.5. LPA induced activation of intracellular signaling cascades that may mediate LPA-regulated BACE1 gene expression

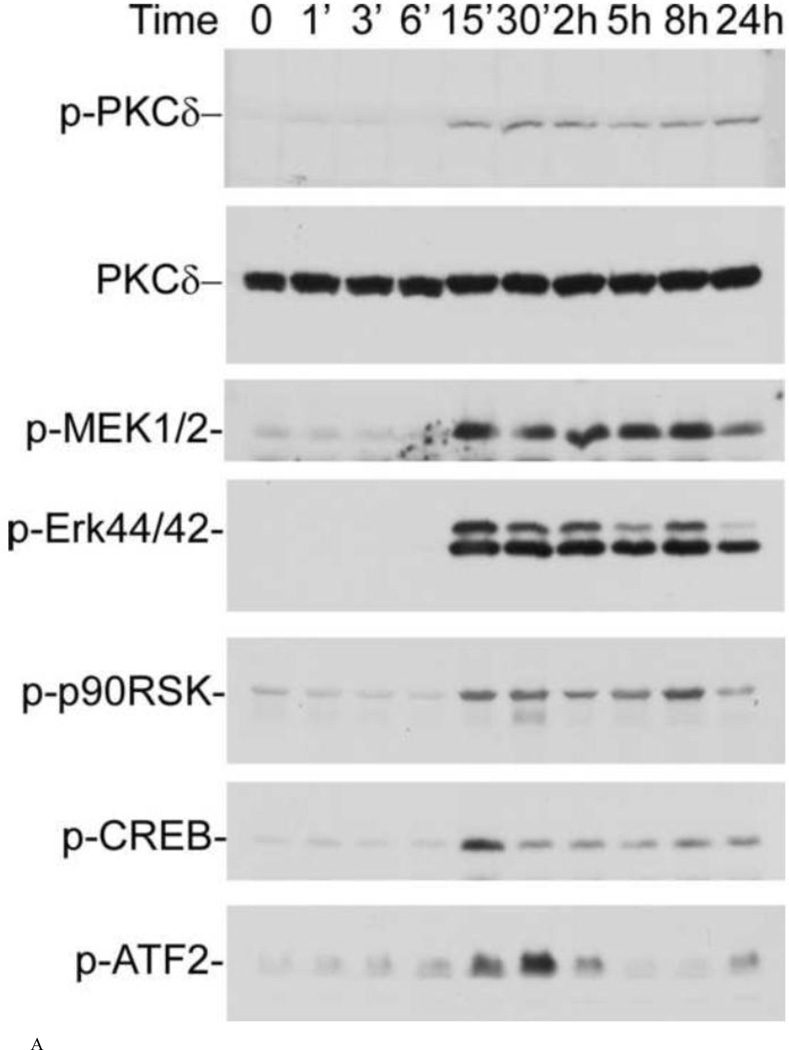

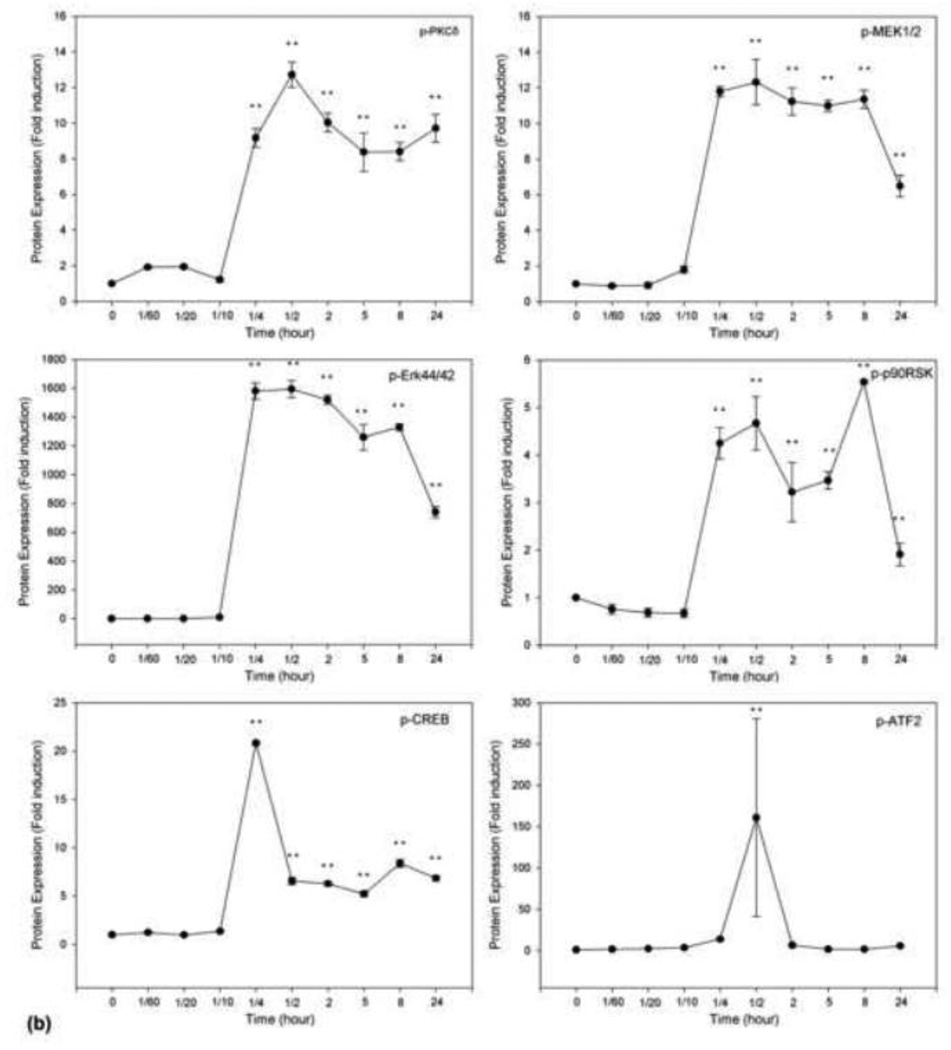

LPA has been shown to induce intracellular signaling through the seven-transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) called LPA receptor that is sensitive to pertussis toxin (PTX), which uncouples GPCR from its Gi/o [29]. To determine the molecular cascades that lead to LPA-induced BACE1 gene expression, we performed a series of experiments to determine which kinases are activated upon LPA stimulation. Starved cells were treated with 25 µM LPA for different lengths of time. As shown in the top panel of Fig. 4a, phosphorylated PKCδ was detected after 15-min treatment with LPA. This membrane was reprobed with antibody against PKCδ protein to confirm the even loading of samples (second panel). When the same samples were analyzed for the activation of other interested molecules, it was found that, in addition to PKCδ, MEK, MAPK (Erk44/42) and p90RSK were rapidly phosphorylated in response to LPA. Moreover, the two transcriptional factors, CREB and ATF2 were also rapidly and transiently phosphorylated. It is notable that both CREB and ATF2 are members of the ATF/CREB transcription factor family [30]. The phosphorylation of these transcription factors by LPA treatment is in agreement with the observation that LPA induced increased CREB binding activity (Fig. 3). Thus, these results strongly suggest that CREB mediates the up-regulation of BACE1 expression by LPA. This speculation is also supported by the observation that p90RSK mediates CREB phosphorylation in response to activation of upstream PKCδ [31].

Fig. 4.

Time course of LPA-induced activation of signaling cascades. N2a cells were stimulated with 25 μM LPA, and, at the time points indicated, cell lysates were analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane. Phosphorylated PKCδ (top panel), MEK1/2 (third panel), MAPK (Erk44/42, fourth panel), p90RSK (fifth panel), CREB (sixth panel), and ATF2 (seventh panel) were detected with antibodies against phospho-MEK1/2 (PMEK1/2) (Ser217/221), phospho-MAPK (P-Erk44/42, Thr202/Tyr204), and phospho-p90RSK (P-p90RSK, Ser381), phosphor-CREB (p-CREB), and phosphor-ATF2 (p-ATF-2), respectively (Cell Signaling Technology). The membranes in the top panel were stripped and re-probed with anti-PKCδ antibody to ensure equal loading. (a) representative of three repeated Western blot results; (b) quantification and statistical analysis of the western blot results shown in (a).

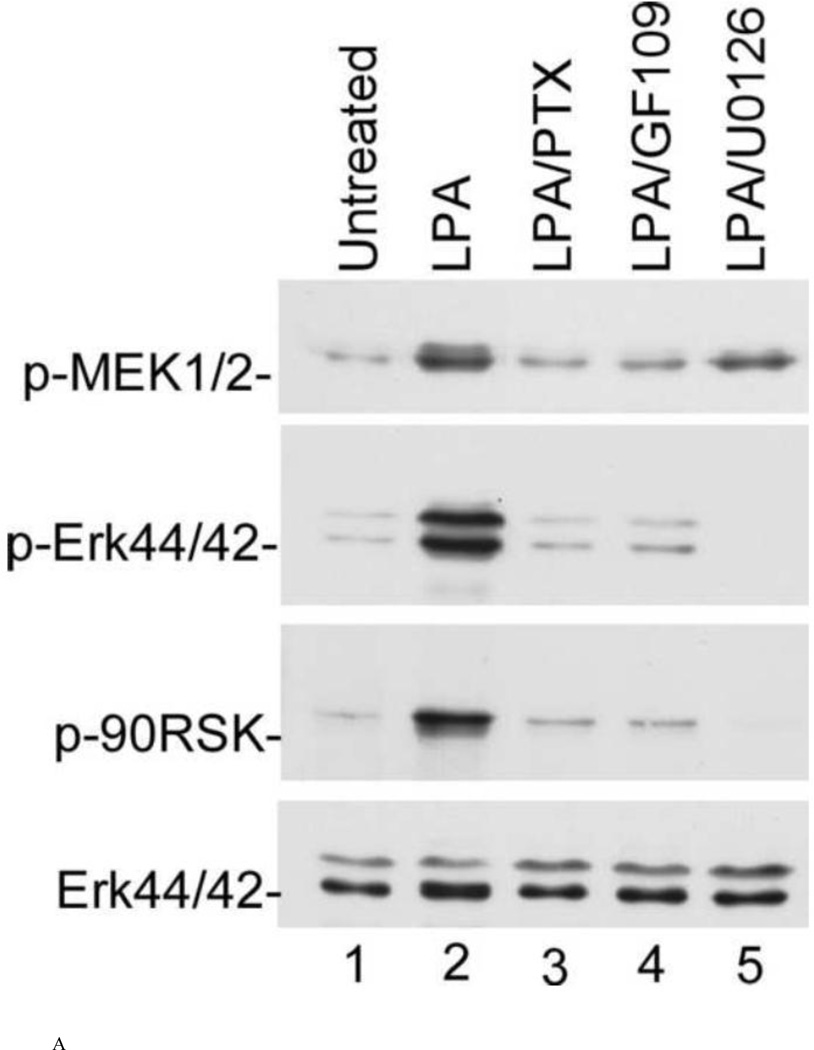

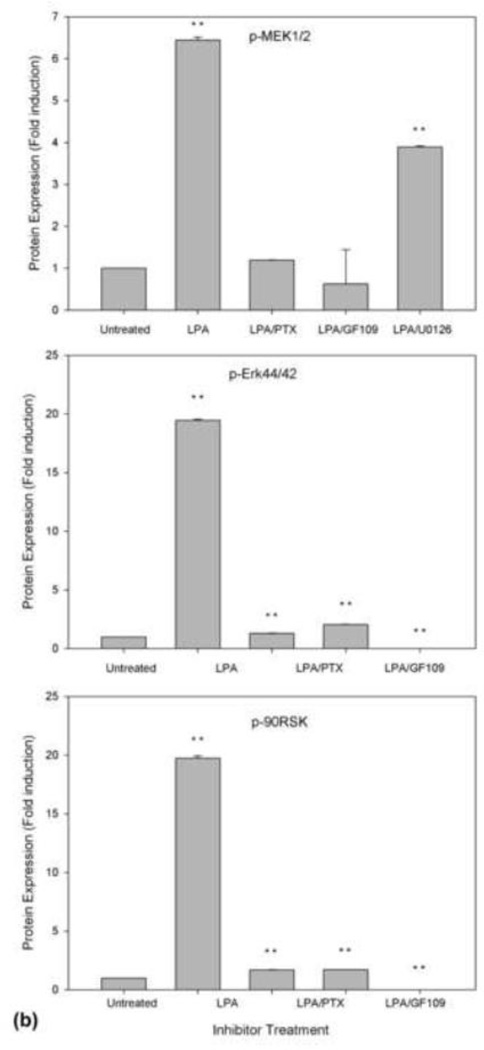

3.6. p90RSK is downstream of PKC and MEK

Next, we performed a series of experiments using specific inhibitors to further determine the sequential relationship of these cascades. To do so, cells were pretreated with appropriate inhibitors for 30 min prior to treatment with 25 µM LPA for 15 min. As shown in Fig. 5, PTX (lane 3), a G-protein inhibitor specific to Gαi, and GF109 (lane 4), a PKC inhibitor, strongly inhibited the phosphorylation of MEK (top panel), MAPK (second panel), and p90RSK (third panel), indicating that MEK, MAPK, and p90RSK are downstream of the PTX-sensitive Gαi subfamily of G-protein and PKC. In addition, when the cells were treated with U0126, an MEK-specific inhibitor, as shown in lane 5, U0126 completely inhibited the activation of MAPK (second panel) and p90RSK (third panel), indicating that activation of MEK is required for activation of MAPK and p90RSK stimulated by LPA. These results indicate that p90RSK is downstream of PKC and MEK. The bottom panel is the reprobe of the membrane in the second panel with an antibody against Erk44/42 protein to confirm the even loading of the samples.

Fig. 5.

Effect of PTX, GF109, and U0126 on the activation of MEK (top panel), MAPK (second panel), and p90RSK (third panel). N2a cells were pretreated with 100 ng/ml pertussis toxin for 16 h or pretreated with 5 µM GF109 or 10 μM U0126 for 30 min prior to the addition of 25 μM LPA for 15 min. The cell lysates were analyzed as described in Fig. 4. The membranes of the second panel were stripped and re-probed with anti-Erk antibody to ensure equal loading. (a) representative of three repeated Western blot results; (b) quantification and statistical analysis of the western blot results shown in (a).

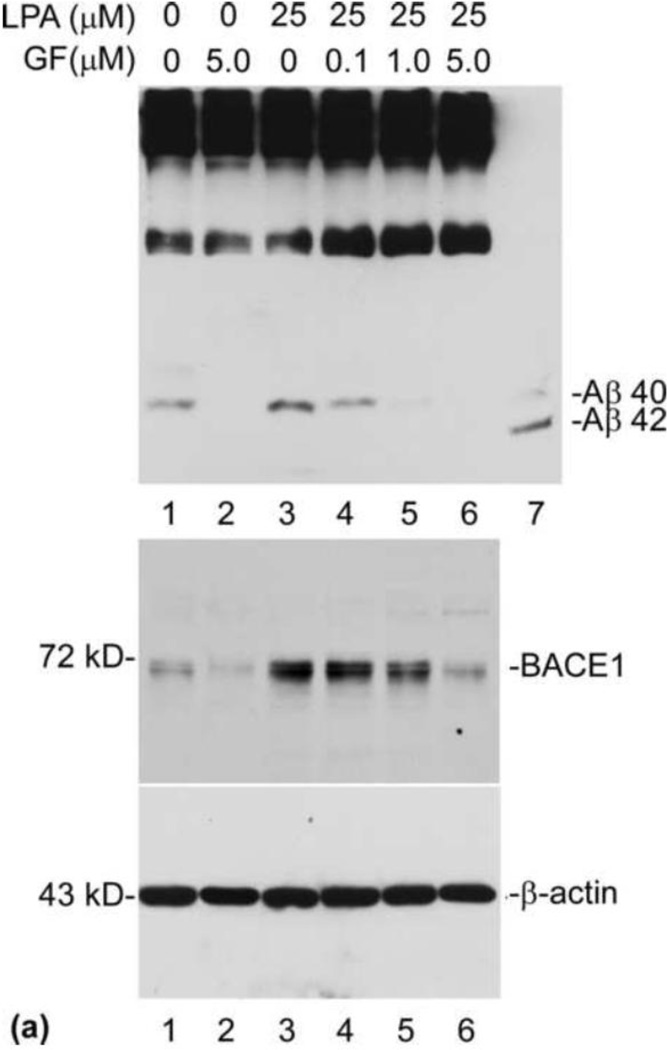

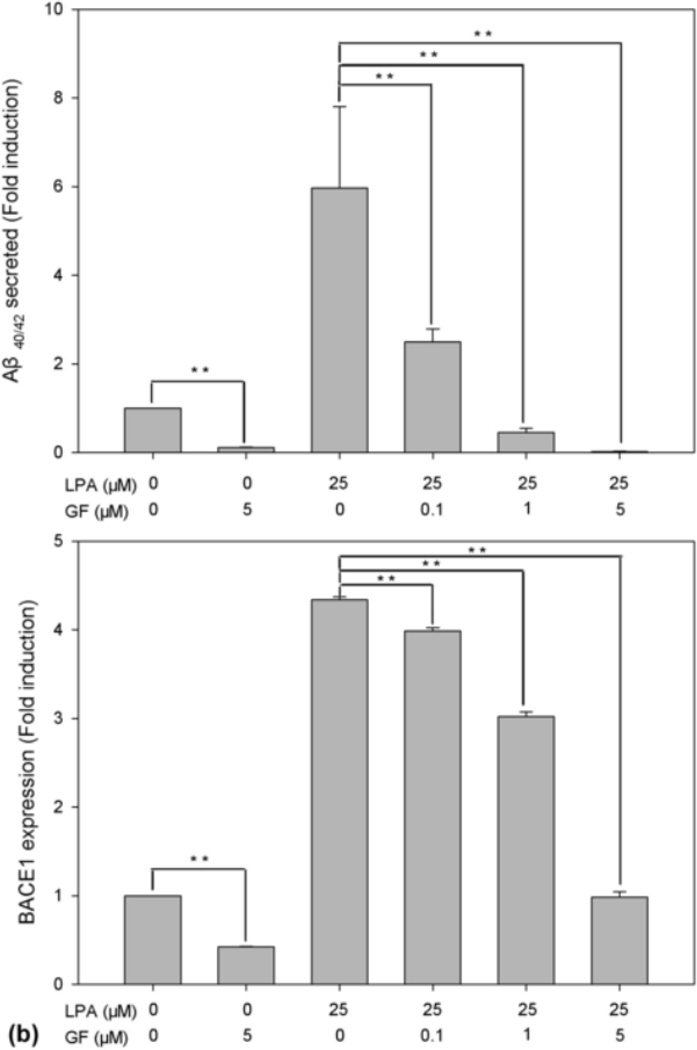

3.7. PKC inhibitor GF attenuated LPA-induced increase in Aβ formation

The data presented above strongly suggest that PKC is an upstream effector in the LPA-induced intracellular signaling cascades that may mediate LPA-induced increase in Aβ formation. Thus, we performed an experiment to determine the effect of PKC inhibitor on LPA-induced Aβ formation. To do so, cells were pretreated with PKC inhibitor GF109203X for 30 min prior to treatment with 25 µM LPA for 24 h. After treatment with LPA for 24 h, Aβ was immunoprecipitated from the CM with 6E10 and analyzed by urea (8M) SDS-PAGE (13%) followed by Western blot using 6E10. As shown in the top panel of Fig. 6a, GF109203X dose-dependently and statistically significantly inhibited LPA-induced Aβ formation (compare lanes 4, 5, and 6 with lane 3 in [a] and as indicated in the upper panel in [b]). It was also noted that, at a high concentration (5 µM), GF109203X also strongly inhibited the basal level of Aβ formation (compare lane 2 with lane 1). Next, we determined the effect of GF109203X on LPA-induced expression of BACE1. The cell lysates from the above dose-curve experiment were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (8 %) followed by Western blot analysis. As shown in the middle panel of (a) and the lower panel of (b), GF109203X caused a dose-dependent and statistically significant decrease in LPA-induced BACE1 expression (compare lanes 4, 5, and 6 with lane 3). Interestingly, it was found that, at a high concentration (5 µM), GF also strongly inhibited the basal level of BACE1 expression (compare lane 2 with lane 1). These results strongly suggest that the inhibitory effect of GF on Aβ formation is mediated by inhibition of BACE1 expression.

Fig. 6.

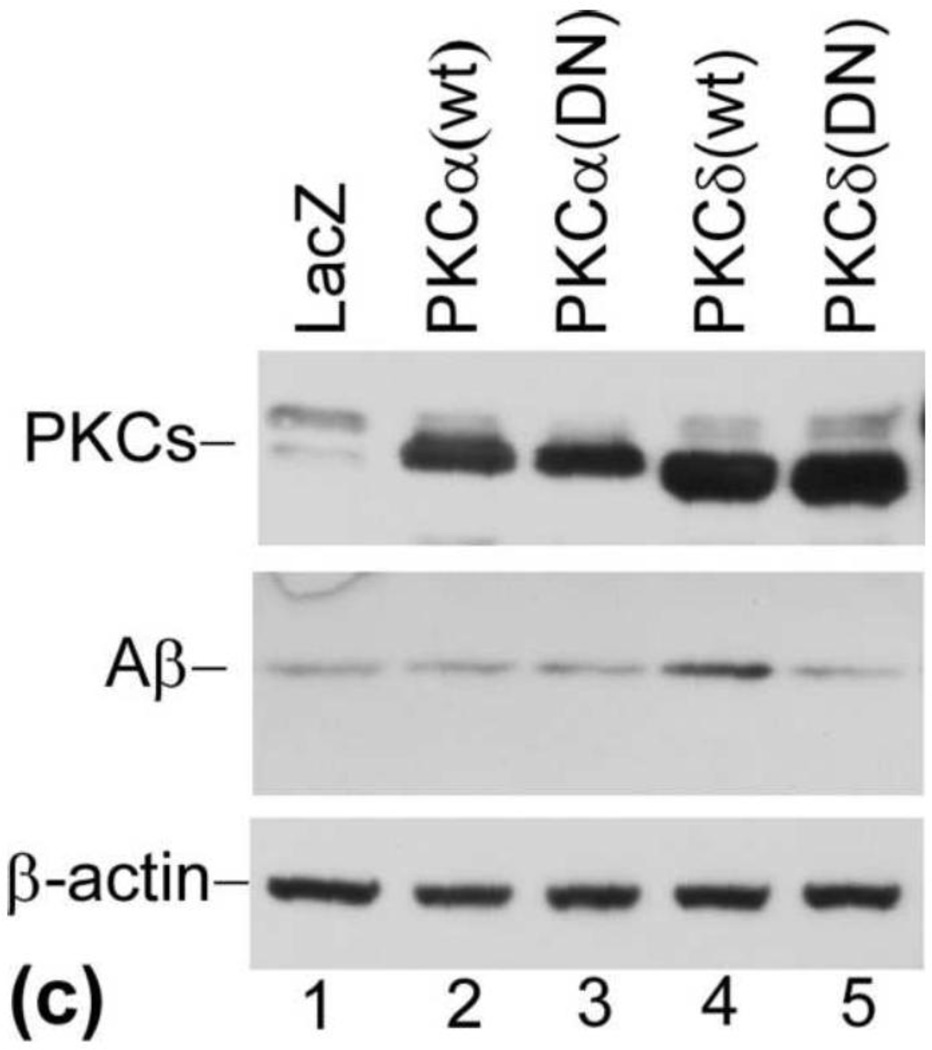

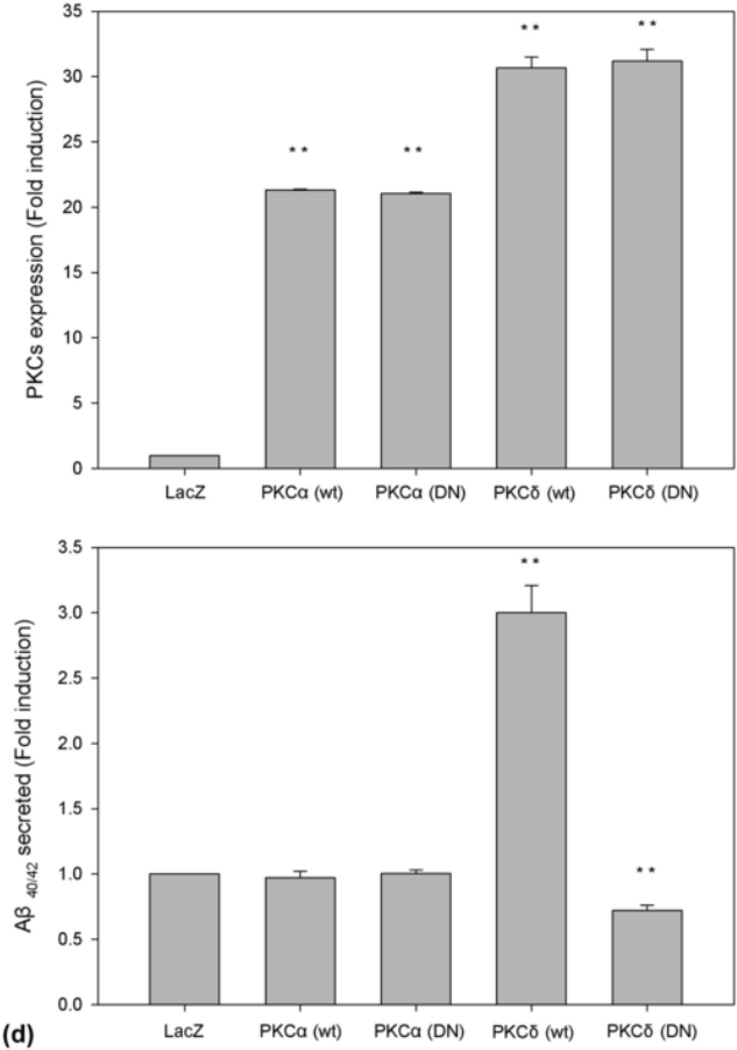

PKCδ regulates Aβ production. (a) PKC inhibitor GF109203X (GF) blocks LPA-induced Aβ formation. Prior to treatment with LPA, cells were pretreated with PKC inhibitor GF at various concentrations for 30 min and then treated with LPA at indicated concentrations for 24 h. Secreted Aβ was immunoprecipitated from CM (top panel) was analyzed by 13 % urea SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting using 6E10. BACE1 expression was determined by direct analyzing the cell lysates (second panel). Third panel is the reprobe of the membrane in the second with anti-β-actin to ensure even loading of the samples. Lane 7 is the Aβ40/42 standard mix. (b) Western blotting signals from three repeated experiments shown in (a) were quantified, and the control and LPA-treated samples compared with GF-treated samples. (c) Overexpression of PKCδ increases Aβ production. Twenty-four hours after infection with recombinant adenovirus-expressing PKC variants, cell lysates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blot analysis using a mix of anti-PKCα and PKCδ antibodies (top panel, Cell Signaling Technology). (d) Quantification and statistical analysis of the Western blot results shown in (c). Aβ was immunoprecipitated from CM (middle panel). Bottom panel is the reprobe of the membrane in the top panel for β-actin. Statistical significances were calculated by GF-treated and non-GF-treated samples. Statistically significant results are indicated: **p≤0.01.

3.8. Overexpression of PKCδ caused an increase in Aβ production

As shown in Fig. 4, our data show that LPA induces PKCδ activation. To further determine the possible role of PKCδ in LPA-induced Aβ production, we examined the effects of overexpression of wild type PKCδ (PKCδ[wt]) and dominant negative mutant PKCδ (PKCδ[DN]) on Aβ production. As controls, wild type PKCα (PKCα[wt]) and dominant negative mutant PKCα (PKCα[DN]) were also included in these experiments. The adenovirus system has been successfully used to deliver genes [high efficiency (99%)] into cultured cells [32–34]. Cells were infected with recombinant adenovirus expressing these PKC variants as described in our previous study [35]. Twenty-four hours after infection, secreted Aβ was immunoprecipitated from conditioned media with 6E10 and analyzed by Western blot using 6E10. Cell lysates were analyzed for the expression of PKC. As shown in Fig. 6c, both PKCα and PKCδ were overexpressed in virus-infected cells (top panel). No differences in the Aβ levels were detected in cells expressing wild type PKCα and dominant negative PKCα in comparison with cells expressing non-related protein LacZ (compare lanes 2 and 3 with lane 1 in the middle panel). Interestingly, an increase in Aβ production was detected in cells expressing wild type PKCδ (compare lane 4 with lanes 1). In contrast, a slightly decrease in Aβ production was detected in cells expressing dominant negative mutant PKCδ (compare lane 5 with lane 1). Quantification of the Western blotting signals indicates the increase in Aβ caused by overexpression of PKCδ is statistically significant (d). These data suggest PKCδ plays a role in regulating Aβ formation.

4. Discussion

LPA is one of the most bioactive components of oxLDL and has been found to be a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease [36]. LPA has also been implicated in AD development by many recent studies, for review see [17]. LPA is present in several biological fluids (serum, plasma, aqueous humor) [37]. As a component of oxLDL, LPA can be formed by mild oxidization of LDL [36] and synthesized and released by several cell types (platelets, fibroblasts, adipocytes, cancer cells) [37]. The key enzyme that governs the synthesis of LPA is lysophospholipase D (lysoPLD), which is identical to autotaxin, a tumor cell motility-stimulating factor [29]. In this regard, it is notable that a recent study revealed that autotaxin expression is enhanced in frontal cortex of AD patients, suggesting that autotaxin and its product LPA may be involved in AD pathology [38]. Interestingly, in an effort to study the pathogenetic effect of oxLDL, our data revealed that LPA, the major bioactive component of oxLDL, can enhance Aβ production. This result prompted us to further determine the mechanism by which LPA upregulates Aβ production. Since Aβ peptide is produced from its precursor APP, we first examined whether LPA treatment has any effect on APP expression. Our data revealed that LPA treatment has no effect on APP expression under our experimental conditions. There are two enzymes play key roles in APP processing and Aβ production, the β-secretase, which produces the N-terminal of Aβ, and γ-secretase, which produces the C-terminal of Aβ [9]. Next, we determined the effect of LPA on the expression levels of these secretases. Our results demonstrated that LPA treatment had no effect on the expression levels of the four components of γ-secretase, PS1, NCT, Aph-1α, and Pen-2. However, our time course experiments clearly showed that LPA induced an increase in the expression level of β-secretase, BACE1. These results strongly suggest that LPA causes an increase in Aβ production by up-regulating β-secretase expression. This finding also suggests that oxLDL may contribute to Alzheimer’s disease, at least in part, via upregulating β-secretase expression and Aβ formation. In support of our findings, HNE, the other component of oxLDL, has been recently shown to induce the expression and activity of BACE1 [39]. Moreover, a recent study has shown that oxidative stress elevates β-secretase protein and activity in vivo in an animal model [40].

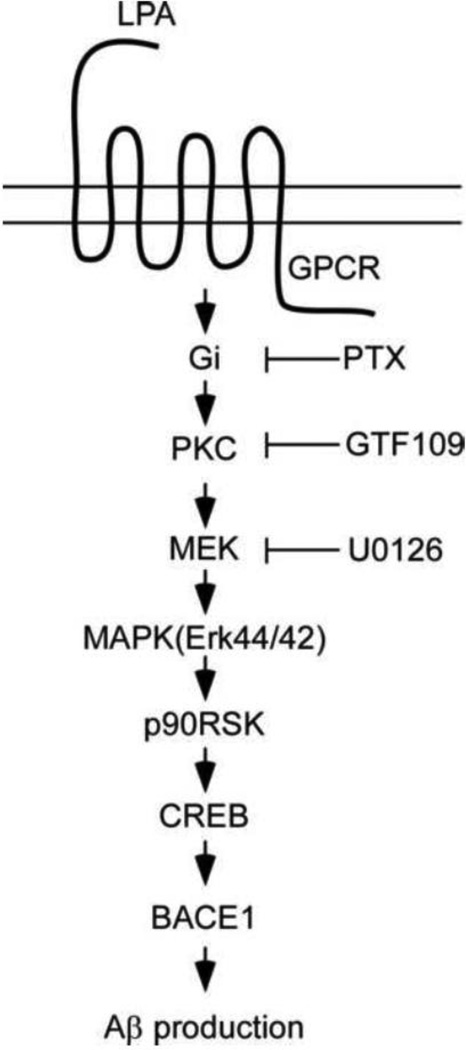

Our data further suggest that LPA upregulates BACE1 expression at the transcriptional level by increasing the expression level of BACE1 mRNA. DNA sequence analysis of the promoter region of BACE1 gene has revealed that there are one CRE site, one Sp1 site, and several other transcription factor binding sites, such as AP-1, AP-2, AP-3, and SRE sites [27]. It was also reported that overexpression of the transcription factor Sp1 potentiates BACE gene expression [27]. To determine which transcriptional factor is responsible for LPA-induced BACE1 expression, we carried out a gel-shift experiment, and our results revealed that the binding activity of CREB to the CRE site of the BACE1 promoter was significantly increased upon LPA treatment, while the binding activities of Sp1, AP-1, and SRF were not changed. These results indicate that BACE1 expression can be regulated by different transcriptional factors under different conditions. Our results that LPA treatment resulted in an increased binding activity of CREB to the BACE1 promoter suggest that in response to LPA stimulation, it is CREB, but not Sp1, AP_1, or SRE, that mediates the upregulation of BACE1 expression. This notion is further strongly supported by our findings that LPA induced the activation of a series of intracellular signaling cascades that led to the activation of CREB. Our results revealed that LPA induced activation of PKC, MEK, MAPK, and p90RSk with PKC as the most upstream and p90RSK as the most downstream elements in the LPA-induced signaling cascades, which are sensitive to PTX, a specific inhibitor of certain G proteins. Given the fact that p90RSK has been reported to mediate CREB phosphorylation in response to activation of upstream PKCδ [31], as summarized in Fig. 7, our data strongly suggest that LPA-induced BCE1 promoter activation is mediated by PKCδ-MEK-MAPK-p90RSK-CREB signaling cascades.

Fig. 7.

A schematic summary of the molecular pathway by which LPA induces Aβ production.

Previous studies have shown that PKC is involved in regulation of α-secretase-mediated APP processing, and specifically, in up-regulation of the secretion of sAPPα generated by α-secretase [41–44]. Studies have also shown that in various types of cells, PKCε is implicated in regulating α-secretase-mediated APP processing [45–47]. In some types of cells, PKCα and PKCβ isoforms may also be involved in the regulation of α-secretase-mediated APP processing [45, 48], but PKCδ is not involved [47, 49]. These studies suggest a possibility that PKC may indirectly regulate Aβ formation by promoting α-secretase-mediated processing of APP. However, whether PKC has any direct regulatory effect on Aβ formation remains unclear. In this study, we examined the effects of these PKC isoforms on Aβ formation. As a result, our data revealed, for the first time, that overexpression of PKCδ, but not PKCα, leads to increased production of Aβ. This finding provided further strong support to our notion that PKCδ functions as an important upstream effector in the LPA-induced intracellular pathway that leads to the activation of the BACE1 promoter and increased expression of β-secretase and eventually results in an increase in the production of Aβ as discussed above. Given the fact that previous studies have shown that activation of PKCδ, unlike PKCα and PKCε, has no effect on α-secretase-mediated APP processing, our data suggest that PKCδ may specifically be involved in β-secretase-mediated APP processing.

In conclusion, the data presented in this study clearly indicate that LPA, the most bioactive component of oxLDL, induces increased production of Aβ. Furthermore, our data indicate that LPA induces increased Aβ production via upregulating β-secretase expression. In addition, our data strongly support the notion that different isoforms of PKC may play different roles in regulating APP processing, and specifically that, different from most other PKC members, such as PKCα, PKCβ, and PKCε, which are implicated in regulating α-secretase-mediated APP processing, PKCδ, a member of the novel PKC subfamily, is involved in LPA-induced upregulation of β-secretase expression and Aβ production. These findings provide biochemical evidence that suggests that the cardiovascular risk factor LPA, a major bioactive lipid component of oxLDL, may contribute to AD by increasing Aβ production and that different isoforms of PKC may regulate APP processing and Aβ production in different ways.

Highlights.

Evidence suggests that vascular factors play an important role in pathogenesis of AD.

First, we found that LPA induces increased production of Aβ;

Second, LPA induces increased Aβ production via upregulating β-secretase expression;

Third, PKCδ is involved in LPA-induced β-secretase expression and Aβ production.

Cardiovascular risk factors may contribute to AD by increasing Aβ production.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R181741110 and R21AG039596, an Alzheimer’s Association grant, and a grant from the American Health Assistance Foundation (to XX) and by NIH grant HL107466 (to M-Z C). We thank Ms. Misty R. Bailey for her critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- NFT

neurofibrillary tangles

- Aβ

β amyloid

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- BACE1

β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1

- oxLDL

oxidized low-density lipoprotein

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- LPA

lysophosphatidic acid

- CREB

cAMP response element-binding protein

- APPsw

Swedish mutant APP

- PS1wt

wild type presenilin 1

- CM

conditioned medium

- SRF

serum response element

- CRE

cAMP-responsive element

- PTX

Pertussis toxin

- wt

wild type

- DN

dominant negative

- lysoPLD

lysophospholipase D

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ. Amyloid-beta oligomers: their production, toxicity and therapeutic inhibition. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002;30:552–557. doi: 10.1042/bst0300552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease is a synaptic failure. Science. 2002;298:789–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1074069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:741–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan R, Bienkowski MJ, Shuck ME, Miao H, Tory MC, Pauley AM, Brashier JR, Stratman NC, Mathews WR, Buhl AE, Carter DB, Tomasselli AG, Parodi LA, Heinrikson RL, Gurney ME. Membrane-anchored aspartyl protease with Alzheimer's disease beta-secretase activity. Nature. 1999;402:533–537. doi: 10.1038/990107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vassar R, Bennett BD, Babu-Khan S, Kahn S, Mendiaz EA, Denis P, Teplow DB, Ross S, Amarante P, Loeloff R, Luo Y, Fisher S, Fuller J, Edenson S, Lile J, Jarosinski MA, Biere AL, Curran E, Burgess T, Louis JC, Collins F, Treanor J, Rogers G, Citron M. Beta-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein by the transmembrane aspartic protease BACE. Science. 1999;286:735–741. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hussain I, Powell D, Howlett DR, Tew DG, Meek TD, Chapman C, Gloger IS, Murphy KE, Southan CD, Ryan DM, Smith TS, Simmons DL, Walsh FS, Dingwall C, Christie G. Identification of a novel aspartic protease (Asp 2) as beta-secretase. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 1999;14:419–427. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinha S, Anderson JP, Barbour R, Basi GS, Caccavello R, Davis D, Doan M, Dovey HF, Frigon N, Hong J, Jacobson-Croak K, Jewett N, Keim P, Knops J, Lieberburg I, Power M, Tan H, Tatsuno G, Tung J, Schenk D, Seubert P, Suomensaari SM, Wang S, Walker D, Zhao J, McConlogue L, John V. Purification and cloning of amyloid precursor protein beta-secretase from human brain. Nature. 1999;402:537–540. doi: 10.1038/990114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu X. γ-Secretase Catalyzes Sequential Cleavages of the AβPP Transmembrane Domain. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2009;16:211–224. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casado A, Encarnacion Lopez-Fernandez M, Concepcion Casado M, de La Torre R. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzyme activities in vascular and Alzheimer dementias. Neurochem. Res. 2008;33:450–458. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9453-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cacabelos R, Fernandez-Novoa L, Lombardi V, Corzo L, Pichel V, Kubota Y. Cerebrovascular risk factors in Alzheimer's disease: brain hemodynamics and pharmacogenomic implications. Neurol. Res. 2003;25:567–580. doi: 10.1179/016164103101202002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panza F, D'Introno A, Colacicco AM, Basile AM, Capurso C, Kehoe PG, Capurso A, Solfrizzi V. Vascular risk and genetics of sporadic late-onset Alzheimer's disease. J. Neural Transm. 2004;111:69–89. doi: 10.1007/s00702-003-0071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Draczynska-Lusiak B, Doung A, Sun AY. Oxidized lipoproteins may play a role in neuronal cell death in Alzheimer disease. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 1998;33:139–148. doi: 10.1007/BF02870187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giasson BI, Ischiropoulos H, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. The relationship between oxidative/nitrative stress and pathological inclusions in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002;32:1264–1275. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00804-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bassett CN, Neely MD, Sidell KR, Markesbery WR, Swift LL, Montine TJ. Cerebrospinal fluid lipoproteins are more vulnerable to oxidation in Alzheimer's disease and are neurotoxic when oxidized ex vivo. Lipids. 1999;34:1273–1280. doi: 10.1007/s11745-999-0478-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun YX, Minthon L, Wallmark A, Warkentin S, Blennow K, Janciauskiene S. Inflammatory markers in matched plasma and cerebrospinal fluid from patients with Alzheimer's disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2003;16:136–144. doi: 10.1159/000071001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frisardi V, Panza F, Seripa D, Farooqui T, Farooqui AA. Glycerophospholipids and glycerophospholipid-derived lipid mediators: A complex meshwork in Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Prog. Lipid Res. 2011;50:313–330. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parola M, Bellomo G, Robino G, Barrera G, Dianzani MU. 4-Hydroxynonenal as a biological signal: molecular basis and pathophysiological implications. Antioxid Redox Signal. 1999;1:255–284. doi: 10.1089/ars.1999.1.3-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui MZ, Zhao G, Winokur AL, Laag E, Bydash JR, Penn MS, Chisolm GM, Xu X. Lysophosphatidic acid induction of tissue factor expression in aortic smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003;23:224–230. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000054660.61191.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ge YW, Maloney B, Sambamurti K, Lahiri DK. Functional characterization of the 5' flanking region of the BACE gene: identification of a 91 bp fragment involved in basal level of BACE promoter expression. FASEB J. 2004;18:1037–1039. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1379fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao G, Mao G, Tan J, Dong Y, Cui M-Z, Kim S-H, Xu X. Identification of a New Presenilindependent ζ-Cleavage Site within the Transmembrane Domain of Amyloid Precursor Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:50647–50650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao G, Cui MZ, Mao G, Dong Y, Tan J, Sun L, Xu X. γ-Cleavage is dependent on ζ-cleavage during the proteolytic processing of amyloid precursor protein within its transmembrane domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:37689–37697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507993200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SH, Leem JY, Lah JJ, Slunt HH, Levey AI, Thinakaran G, Sisodia SS. Multiple effects of aspartate mutant presenilin 1 on the processing and trafficking of amyloid precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:43343–43350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui MZ, Laag E, Sun L, Tan M, Zhao G, Xu X. Lysophosphatidic acid induces early growth response gene 1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells: CRE and SRE mediate the transcription. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006;26:1029–1035. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000214980.90567.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan J, Mao G, Cui MZ, Kang SC, Lamb B, Wong BS, Sy MS, Xu X. Effects of gammasecretase cleavage-region mutations on APP processing and Abeta formation: interpretation with sequential cleavage and alpha-helical model. J. Neurochem. 2008;107:722–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05643.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim KS, Wen GY, Bancher C, Chen CMJ, Sapienza VJ, Hong H, Wisniewski HM. Detection and Quantitation Of Amyloid B-Peptide With 2 Monoclonal Antibodies. Neurosci Res Commun. 1990;7:113–122. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christensen MA, Zhou W, Qing H, Lehman A, Philipsen S, Song W. Transcriptional regulation of BACE1, the beta-amyloid precursor protein beta-secretase, by Sp1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:865–874. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.2.865-874.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cui MZ, Penn MS, Chisolm GM. Native and oxidized low density lipoprotein induction of tissue factor gene expression in smooth muscle cells is mediated by both Egr-1 and Sp1. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:32795–32802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cui MZ. Lysophosphatidic acid effects on atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Clin Lipidol. 2011;6:413–426. doi: 10.2217/clp.11.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chyan Y-J, Rawson TY, Wilson SH. Cloning and characterization of a novel member of the human ATF/CREB family: ATF2 deletion, a potential regulator of the human DNA polymerase [beta] promoter. Gene. 2003;312:117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00607-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blois JT, Mataraza JM, Mecklenbrauker I, Tarakhovsky A, Chiles TC. B cell receptor-induced cAMP-response element-binding protein activation in B lymphocytes requires novel protein kinase Cdelta. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:30123–30132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi T, Kawahara Y, Okuda M, Ueno H, Takeshita A, Yokoyama M. Angiotensin II stimulates mitogen-activated protein kinases and protein synthesis by a Ras-independent pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:16018–16022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.16018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hedges JC, Dechert MA, Yamboliev IA, Martin JL, Hickey E, Weber LA, Gerthoffer WT. A role for p38(MAPK)/HSP27 pathway in smooth muscle cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:24211–24219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miano JM, Carlson MJ, Spencer JA, Misra RP. Serum response factor-dependent regulation of the smooth muscle calponin gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:9814–9822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan M, Xu X, Ohba M, Ogawa W, Cui MZ. Thrombin rapidly induces protein kinase D phosphorylation, and protein kinase C delta mediates the activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:2824–2828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211523200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siess W, Zangl KJ, Essler M, Bauer M, Brandl R, Corrinth C, Bittman R, Tigyi G, Aepfelbacher M. Lysophosphatidic acid mediates the rapid activation of platelets and endothelial cells by mildly oxidized low density lipoprotein and accumulates in human atherosclerotic lesions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:6931–6936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pagès C, Simon M-F, Valet P, Saulnier-Blache JS. Lysophosphatidic acid synthesis and release. Prostaglandins & Other Lipid Mediators. 2001;64:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(01)00110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Umemura K, Yamashita N, Yu X, Arima K, Asada T, Makifuchi T, Murayama S, Saito Y, Kanamaru K, Goto Y, Kohsaka S, Kanazawa I, Kimura H. Autotaxin expression is enhanced in frontal cortex of Alzheimer-type dementia patients. Neurosci. Lett. 2006;400:97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamagno E, Bardini P, Obbili A, Vitali A, Borghi R, Zaccheo D, Pronzato MA, Danni O, Smith MA, Perry G, Tabaton M. Oxidative stress increases expression and activity of BACE in NT2 neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002;10:279–288. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiong K, Cai H, Luo XG, Struble RG, Clough RW, Yan XX. Mitochondrial respiratory inhibition and oxidative stress elevate beta-secretase (BACE1) proteins and activity in vivo in the rat retina. Exp. Brain Res. 2007;181:435–446. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-0943-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buxbaum JD, Oishi M, Chen HI, Pinkas-Kramarski R, Jaffe EA, Gandy SE, Greengard P. Cholinergic agonists and interleukin 1 regulate processing and secretion of the Alzheimer beta/A4 amyloid protein precursor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:10075–10078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nitsch RM, Slack BE, Wurtman RJ, Growdon JH. Release of Alzheimer amyloid precursor derivatives stimulated by activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Science. 1992;258:304–307. doi: 10.1126/science.1411529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolf BA, Wertkin AM, Jolly YC, Yasuda RP, Wolfe BB, Konrad RJ, Manning D, Ravi S, Williamson JR, Lee VM. Muscarinic regulation of Alzheimer's disease amyloid precursor protein secretion and amyloid beta-protein production in human neuronal NT2N cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:4916–4922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee RK, Wurtman RJ, Cox AJ, Nitsch RM. Amyloid precursor protein processing is stimulated by metabotropic glutamate receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:8083–8087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.8083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jolly-Tornetta C, Wolf BA. Regulation of amyloid precursor protein (APP) secretion by protein kinase calpha in human ntera 2 neurons (NT2N) Biochemistry (Mosc) 2000;39:7428–7435. doi: 10.1021/bi0003846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yeon SW, Jung MW, Ha MJ, Kim SU, Huh K, Savage MJ, Masliah E, Mook-Jung I. Blockade of PKC epsilon activation attenuates phorbol ester-induced increase of alpha-secretase-derived secreted form of amyloid precursor protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;280:782–787. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu G, Wang D, Lin YH, McMahon T, Koo EH, Messing RO. Protein kinase C epsilon suppresses Abeta production and promotes activation of alpha-secretase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;285:997–1006. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rossner S, Mendla K, Schliebs R, Bigl V. Protein kinase Calpha and beta1 isoforms are regulators of alpha-secretory proteolytic processing of amyloid precursor protein in vivo. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001;13:1644–1648. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kinouchi T, Sorimachi H, Maruyama K, Mizuno K, Ohno S, Ishiura S, Suzuki K. Conventional protein kinase C (PKC)-alpha and novel PKC epsilon, but not -delta, increase the secretion of an N-terminal fragment of Alzheimer's disease amyloid precursor protein from PKC cDNA transfected 3Y1 fibroblasts. FEBS Lett. 1995;364:203–206. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00392-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]