Abstract

Background

This study examines the prevalence, correlates, and psychiatric disorders of adults with history of child sexual abuse (CSA).

Methods

Data were derived from a large national sample of the U.S. population. More that 34,000 adults aged 18 years and older residing in households were face-to-face interviewed in a survey conducted during the 2004–2005 period. Diagnoses were based on the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV version. Weighted means, frequencies, and odds ratios of sociodemographic correlates and prevalence of psychiatric disorders were computed. Logistic regression models were used to examine the strength of associations between child sexual abuse and psychiatric disorders, adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, risk factors and other axis I psychiatric disorders.

Results

The prevalence of child sexual abuse was 10.14% (24.8% in men, and 75.2% in women). Child physical abuse, maltreatment, and neglect was more prevalent among individuals with CSA than among those without it. Adults with child sexual abuse history had significantly higher rates of any Axis I disorder and suicide attempts. The frequency, type and number of CSA were significantly correlated with psychopathology.

Conclusions

The high correlation rates of CSA with psychopathology and increased risk for suicide attempts in adulthood suggest the need for a systematic assessment of psychiatric disorders and suicide risk in these individuals. The risk factors for CSA emphasize the need for health care initiatives geared towards increasing recognition and development of treatment approaches for the emotional sequelae CSA as well as early preventive approaches.

Keywords: Child abuse, sexual; epidemiology; trauma; psychopathology; suicide

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, child sexual abuse (CSA) affects approximately 16% of men and 25–27% of women[1, 2], with a broad range of prevalence in other countries around the world[3]. It is associated to poor outcomes including increased prevalence of psychiatric disorders[4–35] and risk of suicide, engagement in high-risk behaviors[18, 36–39], and decreased health-related quality of life[1, 35, 40–42]. Reliable epidemiological data about the prevalence and characteristics of CSA and its psychological impact are needed to improve the health of affected individuals and their families and for the development of effective prevention and treatment interventions.

Child sexual abuse is associated with 47% of all childhood onset psychiatric disorders and with 26% to 32% of adult onset disorders[33, 43]. Being raped, knowing the perpetrator and higher frequency of the abuse are associated with increased odds of psychiatric disorders[44]. Psychological outcomes likely vary with the timing, type of abuse and whether it involves use of force[9, 33, 35, 44]. Child sexual abuse often occurs in the context of a dysfunctional family environment, such as separation from parents, parental psychopathology, and other forms of child abuse including physical abuse and neglect[44]. For example, abuse involving physical penetration and abuse involving a father or stepfather is associated with greater long-term harm[35].

Clinical and epidemiological studies have demonstrated that CSA is strongly associated with the onset and persistence of adult mood and substance use disorders[4, 6, 9, 13, 18, 19, 21, 29, 34, 35, 43, 45, 46]. Individuals with history of CSA are also more likely to develop anxiety disorders, particularly post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or experience psychotic symptoms following sexual abuse[23, 32]. Despite this body of knowledge, fundamental questions about the epidemiology of CSA remain. The link between CSA and suicidal behavior is less well understood, as mixed results have been reported[25]. Specifically, little is known about the association of CSA with psychiatric disorders in adulthood and dose-response effects of CSA on psychiatric disorders[19, 45, 47]. Furthermore, there is scant research regarding the effect of CSA on the risk of psychiatric disorders in general population as opposed to clinical samples, whether that risk is uniform or varies by psychiatric disorder.[1, 3, 6, 9, 34]

The current study builds on prior knowledge by assessing the psychiatric morbidity related to CSA in a nationally representative sample from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), which included psychometrically sound measures of a broad range of psychiatric disorders. Specifically, we sought to: 1) assess the prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of CSA in the general population; 2) identify risk factors for developing psychiatric disorders among CSA victims; 3) investigate the association of CSA with broad range of psychiatric disorders; and, 4) examine dose-response relationships between frequency of CSA and the prevalence of lifetime mental disorders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

The NESARC[48, 49], Waves 1 and 2, was the source of data for the present study. The NESARC target population at Wave 1 was the civilian non-institutionalized population of 18 years and older, residing in households and group quarters. Blacks, Hispanics, and adults aged 18–24 years were oversampled at the design phase of the survey to obtain more reliable estimates for these groups, with data adjusted for oversampling, household- and person-level non-response. Interviews were conducted by experienced professional lay interviewers with extensive training and supervision[48, 49]. Interviewers had 5 years experience working on census and other health-related surveys, and they completed a 5-day training session[1, 46, 50–52]. All procedures, including informed consent, received full ethical review and approval from the U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Office of Management and Budget. After excluding respondents who were ineligible for Wave 2 (e.g. deceased), 34,653 respondents were re-interviewed, and sample weights were developed to additionally adjust for Wave 2 non-response. Weighted data were then adjusted to be representative of the civilian population of the USA on socioeconomic variables based on the 2000 Decennial Census[49].

Assessment

Sociodemographic measures

Sociodemographic measures included sex, race-ethnicity, nativity, age, education, marital status, place of residence, region of the country, employment status, personal and family income, and insurance type.

Diagnostic assessment

All psychiatric diagnoses were made according to DSM-IV-TR Criteria[53] using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV (AUDADIS-IV), Wave 2 version[54, 55], a reliable and valid diagnostic interview designed to be used by trained interviewers. Extensive AUDADIS-IV questions covered DSM-IV criteria for alcohol and drug-specific abuse and dependence for 10 classes of substances. The good to excellent (k = 0.70–0.91) test-retest reliability of AUDADIS-IV substance use diagnoses is documented in clinical and general population samples[56, 57]. Convergent, discriminant, and construct validity of AUDADIS-IV substance use disorder criteria and diagnoses were good to excellent[58, 59]. Mood disorders included DSM-IV major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar I and II, and dysthymia. Diagnoses of MDD ruled out bereavement. Anxiety disorders included DSM-IV panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, specific phobias, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). AUDADIS-IV methods to diagnose these disorders are described in detail elsewhere[60–63].

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was assessed at Wave 2 of the NESARC. Consistent with DSM-IV, lifetime and childhood AUDADIS-IV diagnoses of ADHD required the respondent to meet the DSM-IV symptom thresholds. Subtypes were included as well, accordingly to the DSM-IV definition. Twenty symptom items operationalized the 18 ADHD criteria. Conduct disorder was assessed retrospectively through 20 items that yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.72. All questions included in the AUDADIS-IV reflected CD DSM-IV conduct disorder criteria and the 4 dimensions of the disorder (aggression to people and animals, destruction of property, deceitfulness or theft and serious violations of rules) All criteria had to be endorsed before age 15.

All respondents who had gambled five or more times in at least one year of their life were asked about the symptoms of DSM-IV pathological gambling. Consistent with DSM-IV, lifetime AUDADIS-IV diagnoses of pathological gambling required the respondent to meet at least five of the 10 DSM-IV criteria. Fifteen symptom items operationalized the 10 pathological gambling criteria.

The test-retest reliability and validity of AUDADIS-IV DSM-IV disorders is good to excellent[56, 57, 64–70]. Because of concerns over the validity of psychotic diagnoses in general population surveys as well as the length of the interview, possible psychotic disorders were assessed by asking the respondent if he or she was ever told by a doctor or other health professional that he or she had schizophrenia or a psychotic disorder.

The NESARC survey asked individuals the following questions located in the major depressive episode module: During that time when your mood was at its lowest/you enjoyed or cared the least about things, did you: 1) have thoughts of death?; 2) think about committing suicide?; 3) attempt suicide?. We used the third question to assess a lifetime history of suicide attempt.

Child sexual abuse

Child abuse and trauma was assessed in Wave 2. All questions about adverse childhood events (ACEs) are related to respondents’ first 17 years of life. Questions were adapted from the Adverse Childhood Events study[56, 64, 71– 73] and were originally part of an extensive battery of questions from the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS)[74–76] and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)[76, 77]. Response categories for most scale items were 1 = ‘never’, to 5 = ‘very often’. Response category values were summed across items to produce scales.

Child sexual abuse (CSA) was defined by the four questions that the Adverse Childhood Events study used to assess unwanted sexual experiences before age 18[56, 64, 71–73]: “Before you were 18 years old: 1) How often did an adult or other person touch or fondle you in a sexual way when you didn’t want them to or you were too young to know what was happening?; 2) How often did an adult or other person have you touch their body in a sexual way when you didn’t want them to or you were too young to know what was happening?; 3) How often did an adult or other person attempt to have sexual intercourse with you when you didn’t want them to or you were too young to know what was happening?; and, 4) How often did an adult or other person actually have sexual intercourse with you when you didn’t want them to or you were too young to know what was happening?” Responses to all four questions ranged from 1= “never” to 5= “very often”. Individuals who responded never to all these questions were classified as not having a history of CSA. All other individuals were classified as having history of CSA.

Because CSA is frequently associated with a dysfunctional family environment and other types of child abuse, such as physical abuse and neglect[78, 79], the study incorporated measures of known risk factors for CSA. Those included: 1) history of child physical abuse or neglect; 2) parental psychopathology, comprising parental alcohol and drug use, witnessing of domestic violence, parental incarceration, parental psychiatric problems and parental suicide; and, 3) low family support. History of physical abuse or neglect and parental psychopathology were originally part of the CTS[76]. To assess family support all respondents were queried on four questions, rated on a 5-point Likert scale with 1= “never true” and 5= “very often true”: “I felt there was someone in my family who wanted me to be a success”, “There was someone in my family who helped me feel important”, “Someone in my family believed in me”, and “I felt part of a close-knit family”[1, 34, 44, 74]. Individuals who answered 1–2 to all four questions were rated as having low family support. All four questions were originally part of the emotional neglect section of the CTQ[78].

Statistical analysis

Weighted cross-tabulations were used to calculate the prevalence of psychiatric disorders stratified by presence or absence of CSA history. A series of logistic regression analyses yielded odds ratios (OR), indicating associations of sociodemographic characteristics and other risk factors, including other types of abuse and parental psychopathology as predictors and CSA as the outcome variable. A second set of logistic regressions examined CSA as predictor and each lifetime Axis I psychiatric disorder as the outcome. Separate analyses assessed dose-response relationships between number of types of CSA, frequency, and type of CSA and current psychiatric disorders, as well as life time psychiatric disorders. In all sets of analyses, respondents without CSA served as the referent group. To guard against the possibility of sociodemographic characteristics and childhood risk factors influencing the association between CSA and each psychiatric disorder, multiple logistic regressions were computed to yield adjusted odds ratios (AORs) by controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, other comorbid psychiatric disorders, and other potential risk factors, such as parental psychopathology, perceived family support, and other types and number of child abuse (e.g., physical abuse or neglect).

Prevalence, frequency of types of CSA, as well as number of CSA suffered and specific types of CSA and their relationship to different types of psychiatric diagnoses were also computed. Due to low number of cases and similarities between two categories of the variables of frequency of abuse (“fairly often” and “very often”) were merged and named the variable “often.” In order to estimate the independent effect of the different types of CSA, we examined the effect of each type of CSA on the risk of psychiatric disorders, adjusting for all other types of sexual abuse.

We consider two percentage estimates significantly different from each other if their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) do not overlap. Odd ratios (ORs) are considered significant if their 95% CIs do not include 1. All standard errors and 95% CIs were estimated using SUDAAN[73], to adjust for the design effects of the NESARC.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Individuals With and Without a History of Child Sexual Abuse (CSA).

| CSA (N= 3786) |

Non- CSA (N= 30431) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% C.I.) | % | (95% C.I.) | OR | (95% C.I.) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 24.83 | 23.11, 26.64 | 50.65 | 49.92, 51.38 | 0.32 | 0.29, 0.35 |

| Women* | 75.17 | 73.36, 76.89 | 49.35 | 48.62, 50.08 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White* | 69.51 | 66.61, 72.26 | 71.17 | 67.91, 74.23 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Black | 13.41 | 11.53, 15.55 | 10.78 | 9.52, 12.18 | 1.27 | 1.12, 1.45 |

| Asian | 2.06 | 1.41, 3.02 | 4.45 | 3.50, 5.64 | 0.47 | 0.34, 0.66 |

| Native American | 3.76 | 2.97, 4.75 | 1.99 | 1.66, 2.39 | 1.93 | 1.48, 2.53 |

| Hispanic | 11.25 | 9.21, 13.69 | 11.61 | 9.38, 14.28 | 0.99 | 0.86, 1.14 |

| Nativity | ||||||

| Born in the United States* | 90.14 | 87.86, 92.02 | 85.82 | 82.77, 88.4 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Born in a Foreign Country | 9.86 | 7.98, 12.14 | 14.18 | 11.60, 17.23 | 0.66 | 0.57, 0.77 |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married or cohabiting* | 59.33 | 57.45, 61.19 | 64.39 | 63.36, 65.39 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 24.19 | 22.62, 25.84 | 18.16 | 17.61, 18.72 | 1.45 | 1.31, 1.60 |

| Never married | 16.48 | 15.04, 18.02 | 17.46 | 16.53, 18.42 | 1.02 | 0.91, 1.15 |

| Education | ||||||

| < High school | 13.15 | 11.85, 14.57 | 14.02 | 13.12, 14.96 | 0.89 | 0.78, 1.00 |

| High school graduate | 21.41 | 19.62, 23.31 | 24.08 | 23.16, 25.03 | 0.84 | 0.75, 0.94 |

| Some college or higher* | 65.44 | 63.20, 67.63 | 61.90 | 60.73, 63.06 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Urbanicity | ||||||

| Rural | 16.75 | 15.12, 18.53 | 16.24 | 15.14, 17.40 | 1.04 | 0.92, 1.17 |

| Urban* | 83.25 | 81.47, 84.88 | 83.76 | 82.60, 84.86 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 18.12 | 15.42, 21.17 | 17.72 | 15.51, 20.16 | 1.06 | 0.91, 1.23 |

| Midwest | 18.37 | 15.83, 21.20 | 18.55 | 16.46, 20.85 | 1.03 | 0.90, 1.17 |

| South | 39.02 | 35.39, 42.77 | 38.34 | 35.27, 41.50 | 1.05 | 0.94, 1.18 |

| West* | 24.50 | 21.97, 27.21 | 25.39 | 23.57, 27.31 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Insurance | ||||||

| Private* | 74.12 | 72.27, 75.89 | 78.01 | 76.77, 79.20 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Public | 13.75 | 12.32, 15.33 | 10.48 | 9.79, 11.20 | 1.38 | 1.20, 1.59 |

| None | 12.13 | 10.82, 13.57 | 11.51 | 10.73, 12.35 | 1.11 | 0.96, 1.28 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Reference group

The weighted prevalence of sexual abuse before age 18 was 10.14%, of which 24.8% were males and 75.2% females. Compared to individuals with no history of CSA, individuals reporting CSA were more likely to be Black or Native American than Whites; widowed, separated, or divorced than married; and more likely to have public than private insurance. In addition, individuals with history of CSA were less likely to be males, Asian, foreign-born or having completed high school education.

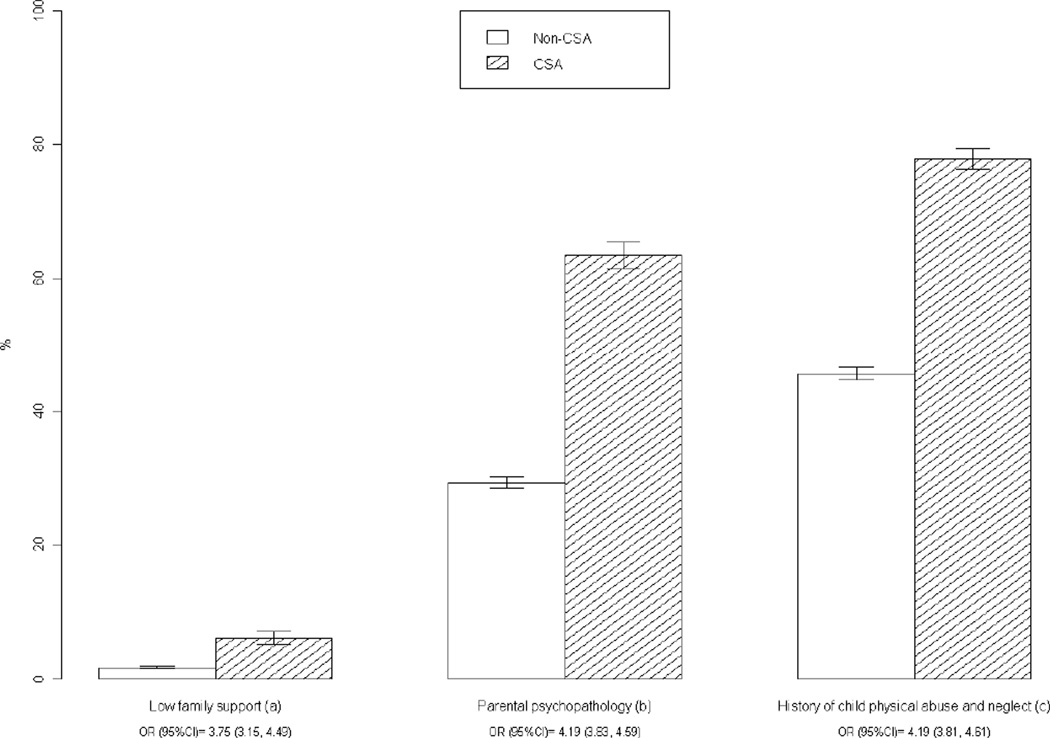

Risk factors of CSA (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Risk Factors of Individuals With and Without a History of Child Sexual Abuse (CSA).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

a History of child physical abuse and neglect = symptoms of child physical abuse/maltreatment, and symptoms of child neglect.

b Parental psychopathology= before age 18 experienced parental alcohol use or drug use, witnessed domestic violence, parent went to prison, parent hospitalized for mental illness, parent committed suicide.

c Low family support (see variable definition in text.)

The prevalence of child physical abuse, maltreatment, and neglect was significantly higher among individuals with CSA than among those without it. Furthermore, respondents with CSA had significantly higher rates of having had a parent with a substance use disorder, witnessing domestic violence, or having had an absent parent before age 18 than respondents without a history of CSA. Child sexual abuse victims had significantly lower levels of perceived family support than those without CSA.

Lifetime psychiatric disorders among individuals with and without CSA (Table 2)

Table 2.

Lifetime Psychiatric Disorders Among Individuals With and Without History of Child Sexual Abuse (CSA).

| CSA (N=3786) |

Non- CSA (N=30431) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | mean (SE) | % | mean (SE) | OR | (95%C.I.) | AORa | (95%C.I.) | |

| Any psychiatric diagnosis | 83.97 | (0.83) | 63.77 | (0.65) | 2.98 | 2.63, 3.37 | 2.21 | 1.93, 2.52 |

| Any Axis I disorder | 81.88 | (0.87) | 61.14 | (0.70) | 2.87 | 2.56, 3.23 | 1.79 | 1.58, 2.03 |

| Any SUD | 55.39 | (1.15) | 44.07 | (0.80) | 1.58 | 1.44, 1.73 | 1.15 | 1.04, 1.28 |

| Nicotine Dependence | 34.19 | (1.10) | 21.87 | (0.51) | 1.86 | 1.69, 2.04 | 1.12 | 1.00, 1.25 |

| Any AUD | 40.53 | (1.16) | 33.94 | (0.76) | 1.33 | 1.21, 1.46 | 0.96 | 0.85, 1.07 |

| Alcohol abuse | 17.93 | (0.85) | 19.48 | (0.53) | 0.90 | 0.80, 1.02 | 1.07 | 0.94, 1.22 |

| Alcohol dependence | 22.60 | (0.89) | 14.47 | (0.39) | 1.73 | 1.55, 1.93 | 1.11 | 0.97, 1.27 |

| Any drug use disorder | 21.31 | (0.83) | 10.95 | (0.33) | 2.20 | 1.99, 2.43 | 1.21 | 1.06, 1.39 |

| Drug abuse | 16.18 | (0.75) | 9.46 | (0.31) | 1.85 | 1.64, 2.08 | 1.08 | 0.93, 1.26 |

| Drug dependence | 8.48 | (0.61) | 2.80 | (0.15) | 3.22 | 2.70, 3.83 | 1.24 | 0.99, 1.57 |

| Any Mood Disorder | 49.15 | (1.00) | 21.14 | (0.37) | 3.61 | 3.31, 3.93 | 1.51 | 1.36, 1.68 |

| Major depressive disorder | 30.35 | (0.96) | 14.80 | (0.29) | 2.51 | 2.28, 2.76 | 1.28 | 1.14, 1.43 |

| Dysthymia | 8.07 | (0.53) | 2.88 | (0.10) | 2.96 | 2.53, 3.47 | 1.19 | 0.97, 1.46 |

| Bipolar disorder | 17.63 | (0.79) | 5.66 | (0.18) | 3.56 | 3.15, 4.03 | 1.33 | 1.14, 1.56 |

| Any anxiety disorder | 55.42 | (1.07) | 26.48 | (0.47) | 3.45 | 3.16, 3.77 | 1.61 | 1.45, 1.78 |

| Panic disorder | 18.17 | (0.83) | 6.16 | (0.19) | 3.38 | 3.00, 3.82 | 1.23 | 1.06, 1.44 |

| Social anxiety disorder | 15.39 | (0.71) | 6.02 | (0.21) | 2.84 | 2.52, 3.20 | 1.02 | 0.87, 1.19 |

| Specific phobia | 27.92 | (0.92) | 13.68 | (0.36) | 2.44 | 2.21, 2.70 | 1.06 | 0.95, 1.20 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 18.81 | (0.82) | 6.36 | (0.21) | 3.41 | 3.02, 3.85 | 1.12 | 0.96, 1.32 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 28.34 | (0.86) | 7.33 | (0.21) | 5.00 | 4.53, 5.52 | 2.05 | 1.82, 2.31 |

| Pathological gambling | 0.59 | (0.13) | 0.38 | (0.05) | 1.57 | 0.96, 2.57 | 0.68 | 0.36, 1.27 |

| Psychotic disorder | 6.12 | (0.47) | 2.85 | (0.18) | 2.22 | 1.81, 2.71 | 1.21 | 0.98, 1.49 |

| ADHD | 7.28 | (0.54) | 1.95 | (0.11) | 3.96 | 3.25, 4.81 | 1.86 | 1.45, 2.38 |

| Conduct disorder | 2.2 | (0.39) | 0.90 | (0.08) | 2.47 | 1.64, 3.70 | 2.13 | 1.36, 3.35 |

| Suicide Attempt | 14.32 | (0.70) | 2.05 | (0.10) | 7.97 | 6.82, 9.30 | 2.60 | 2.13, 3.17 |

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratios; AUD, alcohol use disorder; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SUD, substance use disorder.

Adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, risk factors, and other Axis I comorbid disorders.

Individuals with CSA were significantly more likely than those without CSA to have a psychiatric disorder sometime in their lifetime (OR=2.98, 95% CI: 2.63, 3.37). The most common disorders were nicotine dependence, MDD, PTSD, and specific phobia. In the unadjusted model, individuals with CSA were significantly more likely than those without CSA to have all lifetime axis I disorders, except alcohol abuse and pathological gambling. Individuals with CSA also had higher rates of suicide attempts than those without CSA. The strongest associations were between suicide attempts and PTSD.

Adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, risk factors, and other comorbid psychiatric disorders, decreased the ORs between CSA and all disorders, but the associations remained significant for MDD, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, PTSD, ADHD, conduct disorder, and suicide attempts.

12-Month prevalence of psychiatric disorders among individuals with and without CSA (Table 3)

Table 3.

12-Month Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders Among Individuals With and Without History of Child Sexual Abuse (CSA).

| CSA (N=3786) |

Non- CSA (N=30431) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | mean (SE) | % | mean (SE) | OR | (95% C.I.) | AORa | (95% C.I.) | |

| Any psychiatric diagnosis | 64.64 | (1.11) | 40.30 | (0.52) | 2.71 | 2.44, 3.00 | 1.96 | 1.76, 2.18 |

| Any Axis I disorder | 53.63 | (1.11) | 31.91 | (0.45) | 2.47 | 2.26, 2.70 | 1.81 | 1.65, 1.99 |

| Any SUD | 29.68 | (1.13) | 20.27 | (0.80) | 1.66 | 1.49, 1.85 | 1.28 | 1.14, 1.44 |

| Nicotine Dependence | 21.93 | (1.00) | 13.02 | (0.51) | 1.88 | 1.67, 2.11 | 1.27 | 1.11, 1.45 |

| Any AUD | 11.85 | (0.70) | 9.46 | (0.76) | 1.29 | 1.12, 1.48 | 1.07 | 0.91, 1.26 |

| Alcohol abuse | 5.03 | (0.41) | 5.33 | (0.53) | 0.94 | 0.79, 1.12 | 1.05 | 0.86, 1.29 |

| Alcohol dependence | 6.82 | (0.52) | 4.13 | (0.39) | 1.70 | 1.44, 2.01 | 1.19 | 0.98, 1.45 |

| Any drug use disorder | 4.97 | (0.49) | 2.11 | (0.33) | 2.42 | 1.96, 2.99 | 1.33 | 1.02, 1.74 |

| Drug abuse | 3.14 | (0.38) | 1.55 | (0.31) | 2.07 | 1.58, 2.70 | 1.29 | 0.95, 1.76 |

| Drug dependence | 2.16 | (0.36) | 0.67 | (0.15) | 3.27 | 2.22, 4.81 | 1.36 | 0.84, 2.20 |

| Any Mood Disorder | 22.57 | (0.82) | 8.14 | (0.37) | 3.39 | 2.97, 3.64 | 1.38 | 1.22, 1.57 |

| Major depressive disorder | 11.26 | (0.62) | 5.04 | (0.29) | 2.39 | 2.08, 2.76 | 1.08 | 0.92, 1.28 |

| Dysthymia | 1.79 | (0.30) | 0.64 | (0.10) | 2.83 | 1.98, 4.04 | 1.12 | 0.71, 1.77 |

| Bipolar disorder | 10.79 | (0.62) | 2.86 | (0.18) | 4.10 | 3.50, 4.80 | 1.75 | 1.46, 2.11 |

| Any anxiety disorder | 32.83 | (0.96) | 13.08 | (0.47) | 3.25 | 2.96, 3.58 | 1.72 | 1.54, 1.91 |

| Panic disorder | 7.80 | (0.58) | 1.98 | (0.19) | 3.38 | 3.43, 5.12 | 1.61 | 1.25, 2.09 |

| Social anxiety disorder | 7.04 | (0.53) | 2.00 | (0.21) | 3.71 | 3.09, 4.45 | 1.41 | 1.11, 1.79 |

| Specific phobia | 15.19 | (0.74) | 6.64 | (0.36) | 2.52 | 2.21, 2.87 | 1.21 | 1.04, 1.40 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 9.96 | (0.62) | 3.07 | (0.21) | 3.49 | 2.97, 4.11 | 1.22 | 0.97, 1.53 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 13.06 | (0.67) | 3.48 | (0.21) | 4.16 | 3.63, 4.78 | 1.78 | 1.51, 2.10 |

| Psychotic disorder | 2.06 | (0.30) | 0.44 | (0.18) | 4.74 | 3.32, 6.79 | 2.26 | 1.42, 3.60 |

| Suicide Attempt | 14.32 | (0.70) | 2.05 | (0.10) | 7.97 | 6.82, 9.30 | 3.28 | 2.69, 3.99 |

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratios; AUD, alcohol use disorder; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SUD, substance use disorder.

AORs are adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, risk factors, and other lifetime Axis I comorbid disorders.

Those who reported a history of CSA were significantly more likely than those without CSA to have a psychiatric disorder in the past 12-months (OR=2.71, 95% CI: 2.44, 3.00). The most common disorders were nicotine dependence, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, PTSD, and psychotic disorder. Furthermore, the risk of suicide attempt was higher among those with a history of CSA than those without it (OR= 7.97, 95% CI: 6.82, 9.30).

Adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, risk factors, and other comorbid psychiatric disorders, decreased the ORs between CSA and all disorders, but the associations remained significant for nicotine dependence, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, specific phobia, PTSD, psychotic disorder, and suicide attempts.

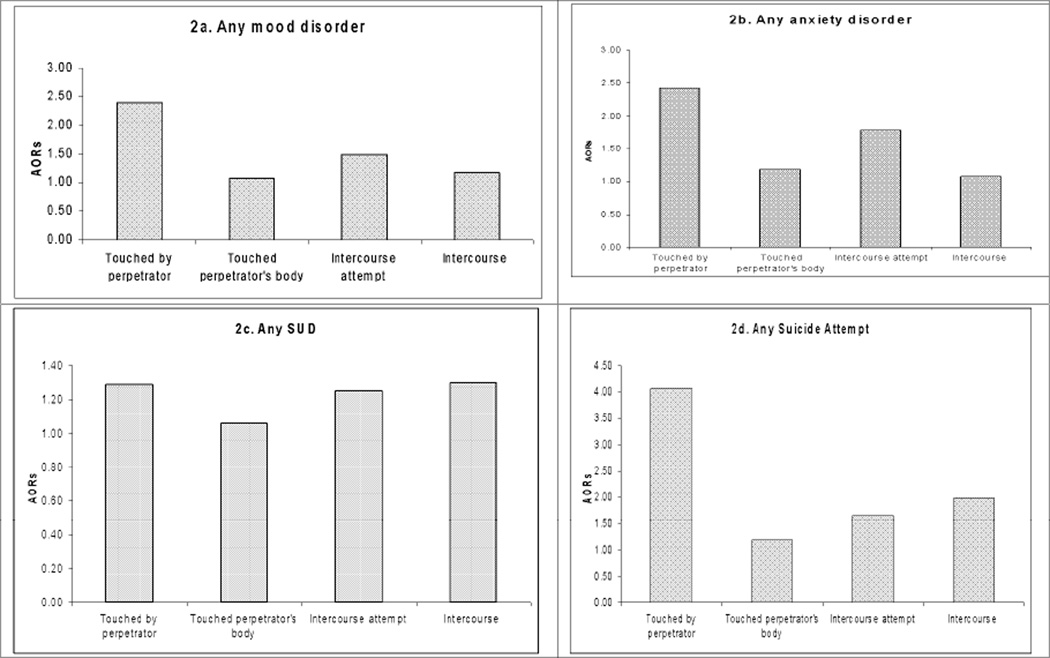

Relationship between frequency, types of CSA, and 12-months psychiatric disorders

After adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, other types of sexual abuse and number of types of sexual abuse, higher frequency of being touched by the perpetrator and having touched the perpetrator‘s body increased the risk of past 12 month mood, anxiety and substance use disorders. A similar association was observed regarding lifetime history of suicide attempt. By contrast, higher frequency of attempted or completed intercourse was associated with increased risk of lifetime history of suicide attempt, but not associated with increased odds of past 12-month mood, anxiety or substance use disorders. Furthermore, there was a dose-response relationship between number of types of child sexual abuse and odds of 12-month mood, anxiety, substance use disorders, as well as suicide attempts (Table 4).

Table 4.

Dose- Response Relationship Between Number of Types and Frequency of CSA and 12-Month Psychiatric Disorders.

| Any mood disorder |

Any anxiety disorder | Any SUD | Any Suicide Attempt |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |||||

| Touched by perpetrator | ||||||||||||

| Never | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Almost never | 1.28 | 0.99 | 1.65 | 1.40 | 1.11 | 1.76 | 1.19 | 0.95 | 1.50 | 1.96 | 1.40 | 2.73 |

| Sometimes | 1.68 | 1.21 | 2.35 | 1.90 | 1.42 | 2.54 | 1.59 | 1.16 | 2.19 | 2.74 | 1.74 | 4.31 |

| Often | 1.75 | 1.09 | 2.82 | 2.07 | 1.38 | 3.11 | 1.81 | 1.15 | 2.84 | 4.09 | 2.38 | 7.04 |

| Touched perpetrator's body | ||||||||||||

| Never | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Almost never | 1.20 | 0.89 | 1.62 | 1.23 | 0.94 | 1.60 | 1.16 | 0.89 | 1.51 | 1.53 | 1.03 | 2.27 |

| Sometimes | 1.54 | 1.09 | 2.18 | 1.32 | 1.51 | 1.09 | 1.38 | 0.96 | 1.98 | 1.68 | 1.07 | 2.64 |

| Often | 1.95 | 1.04 | 3.64 | 1.24 | 2.25 | 1.30 | 1.73 | 1.03 | 2.92 | 1.97 | 1.00 | 3.87 |

| Intercourse attempt | ||||||||||||

| Never | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Almost never | 1.55 | 1.19 | 2.01 | 1.80 | 1.46 | 2.22 | 1.35 | 1.04 | 1.75 | 1.73 | 1.27 | 2.36 |

| Sometimes | 1.47 | 1.01 | 2.13 | 1.62 | 1.19 | 2.21 | 1.01 | 0.70 | 1.47 | 1.73 | 1.09 | 2.76 |

| Often | 1.07 | 0.56 | 2.06 | 1.61 | 0.96 | 2.70 | 1.44 | 0.79 | 2.63 | 2.41 | 1.17 | 4.97 |

| Intercourse | ||||||||||||

| Never | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Almost never | 1.55 | 1.19 | 2.01 | 1.28 | 0.95 | 1.73 | 1.88 | 1.36 | 2.59 | 2.93 | 1.95 | 4.39 |

| Sometimes | 1.50 | 0.96 | 2.35 | 1.32 | 0.91 | 1.92 | 1.62 | 1.10 | 2.39 | 2.81 | 1.66 | 4.78 |

| Often | 1.11 | 0.59 | 2.08 | 1.10 | 0.63 | 1.90 | 1.07 | 0.60 | 1.88 | 2.47 | 1.33 | 4.58 |

| OR | OR | OR | OR | |||||||||

| Number of types of sexual abuse | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 2.85 | 2.40 | 3.40 | 2.71 | 2.34 | 3.13 | 1.43 | 1.21 | 1.70 | 3.58 | 1.44 | 2.72 |

| 2 | 2.83 | 2.34 | 3.42 | 3.18 | 2.70 | 3.74 | 1.46 | 1.20 | 1.71 | 4.53 | 1.59 | 3.01 |

| 3 | 3.84 | 3.05 | 4.84 | 4.60 | 3.81 | 5.56 | 2.10 | 1.67 | 2.63 | 9.15 | 2.45 | 5.21 |

| 4 | 4.19 | 3.48 | 5.04 | 5.22 | 4.33 | 6.29 | 2.01 | 1.67 | 2.43 | 11.89 | 2.63 | 4.60 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; SUD, substance use disorders.

AORs are adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, other types of sexual abuse, and number of types of sexual abuse.

Mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders (SUD) were measured as past 12 months.

Suicide attempt was measured as lifetime.

Being touched by the perpetrator had the highest associations with all psychiatric diagnostic categories: any mood disorder (AOR= 2.40, 95% CI: 1.98, 2.90) (Figure 2a), any anxiety disorder (AOR= 2.43, 95% CI: 2.08, 2.84) (Figure 2b), any SUD (AOR= 1.29, CI: 1.09, 1.53) (Figure 2c), and any suicide attempt (AOR= 4.07, 95% CI: 3.02, 5.48) (Figure 2d). Intercourse attempt significantly increased the risk of having any mood disorder (AOR= 1.49, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.97), any anxiety disorder (AOR= 1.78, 95% CI: 1.47, 2.16), and any suicide attempt (AOR= 1.65, 95% CI: 1.16, 2.35). By contrast, after adjusting for the effect of other types of CSA, touching the perpetrator’s body was not significantly increased the risk any psychiatric disorder.

Figure 2.

a, b, c, d. Relationship Between Type of CSA and Current Psychiatric Disorders.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; SUD, substance use disorders.

a Mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders (SUD) were measured as past 12 months.

b Suicide attempt was measured as lifetime.

AORs are adjusted for other types of sexual abuse (with psychiatric disorders as outcome)

DISCUSSION

In a large, nationally representative sample of US adults, approximately one in 10 individuals had experienced sexual abuse before age 18, in the range of previous epidemiological[33, 34, 38, 44, 80] and clinical studies[12, 13, 21]. The prevalence of CSA was higher among women and among individuals who were widowed, separated or divorced. CSA often co-occurred with child neglect, emotional and physical abuse, as well as parental psychopathology. Individuals with CSA were significantly more likely than those without CSA to meet criteria for a broad range of axis I disorders, and to have a history of suicide attempt. The frequency of the abuse had a dose-response relationship with the odds for psychopathology. The type of the abuse, on the other hand, did not have a strong association with psychopathology.

Consistent with the findings of national and international surveys, CSA was more common among females than males[31, 81], although rates of CSA among males were also high. The true gender distribution of CSA may be obscured by underdetection and underreporting among males, as attention from parents, teachers, pediatricians, and other childcare professionals regarding CSA focuses primarily on girls[34, 44, 81–85]. Boys may be reluctant to disclose sexual abuse due to fear of punishment, stigma against homosexuality, and loss of self esteem, and they may consequently be drawn into the criminal justice or substance abuse treatment systems, contributing to under representation of males with CSA in clinical and community epidemiological studies[86]. Some studies suggest that males may less often report their histories of child sexual abuse than females due to fear of stigma, vulnerability and loss of their masculinity[87, 88]. Despite these sources of potential under-reporting in males, some evidence suggests that boys are sexually abused less often than girls[86]. Men are socialized to behave as sexual initiators and are more often in positions of power, which can sometimes lead to abuse[89, 90]. Women are traditionally expected to show subordination to men, which may make them more vulnerable to abuse perpetrated by male authority figures[90]. Consistent with this interpretation, girls but not boys, are at higher risk of experiencing sexual abuse if they have a stepfather[91]. Nevertheless, prevention and intervention programs should target both genders.

Although no specific psychopathological syndrome has been described as sequelae from CSA in adulthood, our findings indicate that CSA was associated with higher probability of being widowed, separated or divorced[38]. Victims of CSA fear revictimization,[92–95] encounter sexual difficulties, relationship dissatisfaction, and distrust of others, which may interfere with forming and maintaining intimate relations that often characterize marriage[4]. Disturbances in the child’s attachment style may also help explain these relationship difficulties in adulthood[94–96]. Attachment style, emotional support and healthy and positive relationships may play an important role in recovery from CSA[97].

CSA was associated with a broad range of psychiatric disorders particularly PTSD, mood disorders, and ADHD. This pattern suggests that the association of CSA with psychiatric disorders includes general and disorder-specific components. Symptoms of children victims of sexual abuse include feelings of guilt, academic and behavioral problems, increasing the risk for mood disorders[98, 99]. Moreover, genetic characteristics may modulate children’s exposure to environmental insults or their sensitivity to the insults once they experience them[100]. Gene-environment studies have reported interactions between specific genetic characteristics and childhood adversities with development of PTSD[101], antisocial behavior[102, 103], externalizing disorders in general[104], and major depressive disorder[105]. A range of candidate genes, such as 5HTTLPR, MAOA, and DRD1–DRD4, and various others implicated in the central nervous system, have been implicated in psychiatric comorbidity[106]. When looking at the association between CSA and past year psychiatric disorders, we found psychotic disorder has high risk, as compared to the association between CSA and lifetime psychiatric diagnoses. These results shed light on the devastating long term effects of CSA. Since victims of CSA are at risk for revictimization, an explanation can be that accumulation of repeated abuses leads to higher risks of developing a more severe psychopathology.

Suicide attempts were also significantly elevated among individuals with CSA. This association persisted following adjustment for comorbid psychiatric disorders, indicating that CSA is associated with higher odds of suicide attempt even after taking into account the effect of psychiatric disorders. CSA survivors often have feelings of isolation and stigma[107–109], and poor self-esteem[110], which may lead to suicidal behaviors when they are reactivated by similar situations in adulthood[111]. Amygdala abnormalities associated with severe early trauma can also predispose to impulsivity, impaired decision making, and suicidal behavior[112]. Disruptions in the amygdala and other parts of the limbic system and the level of support that a CSA victims receive may be important determinants of long-term adjustment[113].

In accord with previous studies[110], the frequency of abuse was strongly associated with the odds of having a psychiatric disorder. We found the frequency of one type of abuse being strongly associated with developing psychopathology. We also found that frequency of attempted or completed intercourse was not associated with higher odds of psychopathology. This might suggest that some types of CSA, such as attempted or completed intercourse, are so severe that the consequences of a single occurrence are as severe as those of multiple occurrences. At the same time, we found that being touched by the perpetrator was highly associated with any psychiatric disorder, as opposed to having been raped. Thus, the experience of abuse may be more important for the victim than the specific type abuse, leading different types of abuse to generate similar stress. Re-experiencing the abuse may trigger anxiety and contribute to depressed mood or suicidal thoughts and behaviors[9, 35, 114]. Forms of abuse that may appear less severe can have serious consequences on adult mental health if they occur repeatedly, possibly related to enduring dysfunction in brain circuits activated by stress[115], or psychological changes leading to poorer emotional and impulse control regulation[113].

Our study has clinical and preventive implications. The initial effects of CSA include internalizing behaviors such as sleep and eating disturbances, fears and phobias, depression, shame, guilt, anger and hostility and externalizing behaviors such as school problems, truancy, running away, and inappropriate sexual behavior[113]. Therefore, clinical screening for CSA is important for early treatment to reduce the impact of psychological trauma. Children who have a diagnosis of conduct disorder, ADHD, or children who show a variety of externalizing behaviors could be screened by the school or the clinicians for the presence of history of CSA.

Existing brief screening questionnaires can be used in emergency departments, general pediatric clinics, and child mental health agencies and followed up with more comprehensive assessments among children with positive screens[116]. From a broader perspective, training in assessment and mandatory reporting procedures, standard data collection processes, adequate reimbursement, triage and coordination between health care professionals, social work, child protection agencies, law enforcement, and the child's parent or guardian are likely key aspects of successful public policy in this area.

Some psychological interventions have been shown in short-term clinical trials to ameliorate the consequences of CSA. Specifically, trauma-focused CBT with the child and non-offending parent has demonstrated efficacy in adverse psychological effects of sexually abused children[117]. However, much remains to be learned about the optimal balance among different components of trauma-focused CBT, appropriate involvement of non-offending parents in treatment, effectiveness for younger child victims, and for boys[118]. Important questions also remain concerning the appropriate clinical approach to children who following sexual abuse present with few or no symptoms[119], but are nevertheless at high risk over time to deteriorate in their psychological functioning[113]. In addition to psychotherapy, school-based child education programs can help teach children CSA concepts and coping skills for self-defense. Home visitation programs may help to reduce child abuse and neglect by providing the knowledge, skills, and support and improving parenting skills[113].

Our study sheds light on the broad clinical picture that is likely to arise later in life among CSA victims within the general population. It also reflects how certain and frequent psychopathological manifestations, such as suicidal behavior, may be independently linked to CSA. Treatment for adults survivors of CSA include psychopharmacology and psychotherapy to address their self-harmful behaviors, poor sense of self, anxiety disorders and substance abuse and to reduce the possibility of revictimization. Psychotherapy with adult victims of CSA should ideally integrate several techniques to address the patient’s needs appropriately, as well as providing psychoeducation to the patient’s partner into the effects of CSA trauma. Couples that include an individual, who is a survivor of CSA, are at increased risk for a variety of relationship problems, mental health problems, dysfunctional sexual relationships or revictimization. Therefore, couples therapists need an awareness and understanding of the long-term impact of such trauma and be familiarized with the specific interventions that might minimize the damaging effects on intimate relationships.

This study has the limitations common to most large-scale surveys. First, to limit respondent burden, the NESARC assessed CSA with only four questions. Several potential predictors (e.g., support at the time of the abuse) and consequences (e.g., sexual functioning, eating disorders) of CSA were not examined. Second, although the NESARC survey design included group quarters, some special populations, such as those under 18 or respondents in jail or hospitalized at the time of the interview, were not included in the sample. Third, our results are based on data that require recall of lifetime traumatic events and symptoms subsequent to exposure to such trauma, and are subject to the possibility of recall bias. An extensive literature describes false memories related to traumatic events [120]. Fourth, because the exact timing of the abuse is unknown, it is possible that in some cases the onset of the disorder may have preceded the time of the abuse. However, the results of the 12-month prevalence analyses suggest that the influence of this potential bias is likely to be small.

In summary, the national prevalence of CSA is high and it is associated with increased prevalence of psychiatric disorders and suicide attempts. Furthermore, higher odds of psychiatric disorders are associated with the frequency of the abuse. Our study has important clinical implications for pediatricians, psychiatrists, and other mental health professionals who work with children, as early detection and treatment of child abuse might help reduce the onset, persistence or severity of a psychiatric disorder and ameliorate functional impairment. Interventions that prevent and treat CSA can greatly decrease the suffering of the victims and contribute to improved mental health.

Acknowledgments

The NESARC was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). This study is supported by NIH grants NIH grants DA019606, DA020783, DA023200, DA023973, and MH082773 (Dr. Blanco), and the New York State Psychiatric Institute (Dr. Blanco).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Molnar BE, Berkman LF, Buka SL. Psychopathology, childhood sexual abuse and other childhood adversities: relative links to subsequent suicidal behaviour in the US. Psychol Med. 2001 Aug;31(6):965–977. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. Centers for Disease Control. Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. [cited April 22, 2010];1997 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/ace/prevalence.htm.

- 3.Pereda N, Guilera G, Forns M, Gomez-Benito J. The international epidemiology of child sexual abuse: a continuation of Finkelhor (1994) Child Abuse Negl. 2009 Jun;33(6):331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briere J. The long-term clinical correlates of childhood sexual victimization. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1988;528:327–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb50874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briere J. Dissociative symptoms and trauma exposure: specificity, affect dysregulation, and posttraumatic stress. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2006;194(2):78–82. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000198139.47371.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Briere J, Elliott DM. Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-reported childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population sample of men and women. Child Abuse Negl. 2003 Oct;27(10):1205–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briere J, Jordan CE. Violence against women: outcome complexity and implications for assessment and treatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19(11):1252–1276. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269682. [see comment]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briere J, Rickards S. Self-awareness, affect regulation, and relatedness: differential sequels of childhood versus adult victimization experiences. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2007;195(6):497–503. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31803044e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Briere J, Runtz M. Symptomatology associated with childhood sexual victimization in a nonclinical adult sample. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1988;12(1):51–59. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(88)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briere J, Runtz M. The long-term effects of sexual abuse: a review and synthesis. New Directions for Mental Health Services. 1991;(51):3–13. doi: 10.1002/yd.23319915103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Briere J, Scott C. Assessment of trauma symptoms in eating-disordered populations. Brunner-Mazel Eating Disorders Monograph Series. 2007;15(4):347–358. doi: 10.1080/10640260701454360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briere J, Zaidi LY. Sexual abuse histories and sequelae in female psychiatric emergency room patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;146(12):1602–1606. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.12.1602. [see comment]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryer JBNB, Miller JB, Krol PA. Childhood sexual and physical abuse as factors in adult psychiatric illness. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1426–1430. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.11.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carmen EH, Rieker PP, Mills T. Victims of violence and psychiatric illness. Am J Psychiatry. 1984 Mar;141(3):378–383. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen LPMM, Paras ML, Goranson EN, Colbenson KM, Sattler AL, Elamin MB, Seime RJ, Prokop LJ, Zirakzadeh A. Sexual abuse associated with lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Minnesota: Mayo Clinic; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott DM, Briere J. Sexual abuse trauma among professional women: validating the Trauma Symptom Checklist-40 (TSC-40) Child Abuse & Neglect. 1992;16(3):391–398. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90048-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enns MW, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, De Graaf R, Ten Have M, Sareen J. Childhood adversities and risk for suicidal ideation and attempts: a longitudinal population-based study. Psychol Med. 2006 Dec;36(12):1769–1778. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to childhood sexual and physical abuse and adjustment in early adulthood. Child Abuse Negl. 2008 Jun;32(6):607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, Hettema JM, Myers J, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: an epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000 Oct;57(10):953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler RC, Davis CG, Kendler KS. Childhood adversity and adult psychiatric disorder in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Psychol Med. 1997 Sep;27(5):1101–1119. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lanktree C, Briere J, Zaidi L. Incidence and impact of sexual abuse in a child outpatient sample: the role of direct inquiry. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1991;15(4):447–453. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(91)90028-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLeer SV, Deblinger E, Henry D, Orvaschel H. Sexually abused children at high risk for post-traumatic stress disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31(5):875–879. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199209000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLeer SV, Callaghan M, Henry D, Wallen J. Psychiatric disorders in sexually abused children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994 Mar-Apr;33(3):313–319. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199403000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nurcombe B. Child sexual abuse I: psychopathology. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000 Feb;34(1):85–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2000.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Read J, Agar K, Argyle N, Aderhold V. Sexual and physical abuse during childhood and adulthood as predictors of hallucinations, delusions and thought disorder. Psychology & Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice. 2003;76(1):1–22. doi: 10.1348/14760830260569210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Read J, Argyle N. Hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorder among adult psychiatric inpatients with a history of child abuse. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50(11):1467–1472. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.11.1467. [see comment]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reza A, Breiding MJ, Gulaid J, et al. Sexual violence and its health consequences for female children in Swaziland: a cluster survey study. Lancet. 2009 Jun 6;373(9679):1966–1972. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohde P, Ichikawa L, Simon GE, et al. Associations of child sexual and physical abuse with obesity and depression in middle-aged women. Child Abuse Negl. 2008 Sep;32(9):878–887. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romans SE, Gendall KA, Martin JL, Mullen PE. Child sexual abuse and later disordered eating: a New Zealand epidemiological study. Int J Eat Disord. 2001 May;29(4):380–392. doi: 10.1002/eat.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruggiero KJ, McLeer SV, Dixon JF. Sexual abuse characteristics associated with survivor psychopathology. Child Abuse Negl. 2000 Jul;24(7):951–964. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spataro J, Mullen PE, Burgess PM, Wells DL, Moss SA. Impact of child sexual abuse on mental health: prospective study in males and females. Br J Psychiatry. 2004 May;184:416–421. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.5.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Widom CS. Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up. Am J Psychiatry. 1999 Aug;156(8):1223–1229. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilsnack SC, Vogeltanz ND, Klassen AD, Harris TR. Childhood sexual abuse and women's substance abuse: national survey findings. J Stud Alcohol. 1997 May;58(3):264–271. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molnar BE, Buka SL, Kessler RC. Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Public Health. 2001 May;91(5):753–760. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beitchman JH, Zucker KJ, Hood JE, daCosta GA, Akman D, Cassavia E. A review of the long-term effects of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1992;16(1):101–118. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90011-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fleming J, Mullen PE, Sibthorpe B, Bammer G. The long-term impact of childhood sexual abuse in Australian women. Child abuse & neglect. 1999 Feb;23(2):145–159. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wyatt GE, Guthrie D, Notgrass CM. Differential effects of women's child sexual abuse and subsequent sexual revictimization. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1992 Apr;60(2):167–173. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finkelhor D, Hotaling G, Lewis IA, Smith C. Sexual abuse in a national survey of adult men and women: prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors. Child abuse & neglect. 1990;14(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(90)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Widom CS, Kuhns JB. Childhood victimization and subsequent risk for promiscuity, prostitution, and teenage pregnancy: a prospective study. American journal of public health. 1996 Nov;86(11):1607–1612. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.11.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Briere J, Runtz M. Differential adult symptomatology associated with three types of child abuse histories. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1990;14(3):357–364. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(90)90007-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Briere J, Evans D, Runtz M, Wall T. Symptomatology in men who were molested as children: a comparison study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1988;58(3):457–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1988.tb01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Afifi TO, Enns MW, Cox BJ, de Graaf R, ten Have M, Sareen J. Child abuse and health-related quality of life in adulthood. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007 Oct;195(10):797–804. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181567fdd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Feb;67(2):113–123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Finkelhor D. Current information on the scope and nature of child sexual abuse. Future Child. 1994 Summer-Fall;4(2):31–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mullen PE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, Romans SE, Herbison GP. Childhood sexual abuse and mental health in adult life. Br J Psychiatry. 1993 Dec;163:721–732. doi: 10.1192/bjp.163.6.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson JG, Smailes EM. Childhood abuse and neglect: specificity of effects on adolescent and young adult depression and suicidality. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999 Dec;38(12):1490–1496. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. Childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in young adulthood: I. Prevalence of sexual abuse and factors associated with sexual abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996 Oct;35(10):1355–1364. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199610000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP. Co-occurrence of 12-month alcohol and drug use disorders and personality disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004 Apr;61(4):361–368. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, et al. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Mol Psychiatry. 2009 Nov;14(11):1051–1066. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Afifi TO, Boman J, Fleisher W, Sareen J. The relationship between child abuse, parental divorce, and lifetime mental disorders and suicidality in a nationally representative adult sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2009 Mar;33(3):139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sedney MA, Brooks B. Factors associated with a history of childhood sexual experience in a nonclinical female population. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1984 Mar;23(2):215–218. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198403000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peters SD. Child sexual abuse and later psychological problems. In: Wyatt GEaP GJ, editor. Lasting effects of child sexual abuse. Newbury Park: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 53.American Psychiatric Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Fourth ed. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grant BFDD, Hasin DS. The wave 2 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule - DSMIV version. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grant B, Kaplan K, Moore T, Kimball J. 2004–2005 Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions: Source and Accuracy Statement. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2003 Jul 20;71(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hasin DCK, McCloud S, Smith M, Grant BF. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a clinical sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;44(2–3):133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hasin DSGB, Endicott J. The natural history of alcohol abuse: implications for definitions of alcohol use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;(147):1537–1541. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.11.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hasin DSSM, Martin CS, Grant BF, Bucholz KK, Helzer JE. The validity of DSM-IV alcohol dependence: what do we know and what do we need to know? Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;(27):244–252. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000060878.61384.ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grant BFDD. Introduction to the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;(29):74–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004 Aug;61(8):807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grant BFHD, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Smith S, et al. The epidemiology of DSM-IV panic disorder and agoraphobia in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;(67):363–374. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grant BFHD, Blanco C, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, et al. The epidemiology of social anxiety disorder in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;(66):1351–1361. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Canino G, Bravo M, Ramirez R, et al. The Spanish Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability and concordance with clinical diagnoses in a Hispanic population. J Stud Alcohol. 1999 Nov;60(6):790–799. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cottler LB, Grant BF, Blaine J, et al. Concordance of DSM-IV alcohol and drug use disorder criteria and diagnoses as measured by AUDADIS-ADR, CIDI and SCAN. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997 Sep 25;47(3):195–205. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grant BFDD, Hasin DS. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule–DSM-IV Version. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grant BFMT, Shepard J, Kaplan K. Source and Accuracy Statement: Wave 1 of the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grant BFSF, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RPKK. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. J Psychosom Res. 1967 Aug;11(2):213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Institute RT. Research Triangle Institute. Software for Survey Data Analysis (SUDAAN) 9.0. ed. NC: Research Triangle Park; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, Chou PS, Pickering RP. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug and alcohol dependence. 1995 Jul;39(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01134-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hasin D, Carpenter KM, McCloud S, Smith M, Grant BF. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a clinical sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997 Mar 14;44(2–3):133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, et al. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2008 Jan 1;92(1–3):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dong M, Anda RF, Dube SR, Giles WH, Felitti VJ. The relationship of exposure to childhood sexual abuse to other forms of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction during childhood. Child Abuse Negl. 2003 Jun;27(6):625–639. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(03)00105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Giles WH, Anda RF. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health problems: evidence from four birth cohorts dating back to 1900. Prev Med. 2003 Sep;37(3):268–277. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Straus MGR. Physical violence in American families: risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. New Brunswick: Transaction Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry. 1994 Aug;151(8):1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wyatt GE. The sexual abuse of Afro-American and white-American women in childhood. Child Abuse Negl. 1985;9(4):507–519. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(85)90060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Finkelhor D, Dziuba-Leatherman J. Children as victims of violence: a national survey. Pediatrics. 1994 Oct;94(4 Pt 1):413–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wyatt GE, Peters SD. Methodological considerations in research on the prevalence of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1986;10(2):241–251. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(86)90085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Maikovich-Fong AK, Jaffee SR. Sex differences in childhood sexual abuse characteristics and victims' emotional and behavioral problems: Findings from a national sample of youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2010 Apr 16; doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Farber ED, Showers J, Johnson JA, Oshins L. The sexual abuse of children: A comparison of male and female victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1984;13:294–297. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Finkelhor D, Browne A. The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: a conceptualization. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1985 Oct;55(4):530–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Putnam FW. Ten-year research update review: child sexual abuse. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003 Mar;42(3):269–278. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Valente SM. Sexual abuse of boys. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2005 Jan-Mar;18(1):10–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2005.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lab DD, Feigenbaum JD, De Silva P. Mental health professionals' attitudes and practices towards male childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2000 Mar;24(3):391–409. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Finkelhor D. Epidemiological factors in the clinical identification of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1993 Jan-Feb;17(1):67–70. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(93)90009-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Holmes WC, Slap GB. Sexual abuse of boys: definition, prevalence, correlates, sequelae, and management. Jama. 1998 Dec 2;280(21):1855–1862. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.21.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Browne A, Finkelhor D. Impact of child sexual abuse: a review of the research. Psychol Bull. 1986 Jan;99(1):66–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Finkelhor D. Risk factors in the sexual victimization of children. Child Abuse Negl. 1980;4(4):265–273. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Finestone HM, Stenn P, Davies F, Stalker C, Fry R, Koumanis J. Chronic pain and health care utilization in women with a history of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2000 Apr;24(4):547–556. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nelson EC, Heath AC, Madden PA, et al. Association between self-reported childhood sexual abuse and adverse psychosocial outcomes: results from a twin study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002 Feb;59(2):139–145. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Colman RA, Widom CS. Childhood abuse and neglect and adult intimate relationships: a prospective study. Child Abuse Negl. 2004 Nov;28(11):1133–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Finkelhor D, Hotaling GT, Lewis IA, Smith C. Sexual abuse and its relationship to later sexual satisfaction, marital status, religion, and attitudes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1989;4(4):379–399. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rumstein-McKean O, Hunsley J. Interpersonal and family functioning of female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Clin Psychol Rev. 2001 Apr;21(3):471–490. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Alexander PC. Application of attachment theory to the study of sexual abuse. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1992 Apr;60(2):185–195. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Romans SE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, O'Shea ML, Mullen PE. Factors that mediate between child sexual abuse and adult psychological outcome. Psychol Med. 1995 Jan;25(1):127–142. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700028154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shapiro DL, Levendosky AA. Adolescent survivors of childhood sexual abuse: the mediating role of attachment style and coping in psychological and interpersonal functioning. Child Abuse Negl. 1999 Nov;23(11):1175–1191. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kendall-Tackett KA, Williams LM, Finkelhor D. Impact of sexual absue on children: A review and syntheiss of recent empirical studies. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113(1):164–180. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Gene-environment interactions in psychiatry: joining forces with neuroscience. Nature reviews. 2006 Jul;7(7):583–590. doi: 10.1038/nrn1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nelson EC, Agrawal A, Pergadia ML, et al. Association of childhood trauma exposure and GABRA2 polymorphisms with risk of posttraumatic stress disorder in adults. Molecular psychiatry. 2009 Mar;14(3):234–235. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Koenen KC, Saxe G, Purcell S, et al. Polymorphisms in FKBP5 are associated with peritraumatic dissociation in medically injured children. Molecular psychiatry. 2005 Dec;10(12):1058–1059. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt TE, et al. Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science (New York NY. 2002 Aug 2;297(5582):851–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1072290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hicks BM, South SC, Dirago AC, Iacono WG, McGue M. Environmental adversity and increasing genetic risk for externalizing disorders. Archives of general psychiatry. 2009 Jun;66(6):640–648. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cerda M, Sagdeo A, Johnson J, Galea S. Genetic and environmental influences on psychiatric comorbidity: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2010 Oct;126(1–2):14–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science (New York, NY. 2003 Jul 18;301(5631):386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kaufman J, Yang BZ, Douglas-Palumberi H, et al. Social supports and serotonin transporter gene moderate depression in maltreated children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004 Dec 7;101(49):17316–17321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404376101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bradley RG, Binder EB, Epstein MP, et al. Influence of child abuse on adult depression: moderation by the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene. Archives of general psychiatry. 2008 Feb;65(2):190–200. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Coffey P, Leitenberg H, Henning K, Turner T, Bennett RT. Mediators of the long-term impact of child sexual abuse: perceived stigma, betrayal, powerlessness, and self-blame. Child Abuse Negl. 1996 May;20(5):447–455. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Cole PM, Putnam FW. Effect of incest on self and social functioning: a developmental psychopathology perspective. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992 Apr;60(2):174–184. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Briere J, Gil E. Self-mutilation in clinical and general population samples: prevalence, correlates, and functions. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1998 Oct;68(4):609–620. doi: 10.1037/h0080369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Braquehais MD, Oquendo MA, Baca-Garcia E, Sher L. Is impulsivity a link between childhood abuse and suicide? Compr Psychiatry. 2010 Mar-Apr;51(2):121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Briere J, Kaltman S, Green BL. Accumulated childhood trauma and symptom complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21(2):223–226. doi: 10.1002/jts.20317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bagley C, Wood M, Young L. Victim to abuser: mental health and behavioral sequels of child sexual abuse in a community survey of young adult males. Child Abuse Negl. 1994 Aug;18(8):683–697. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Palusci VJ, Palusci JV. Screening tools for child sexual abuse. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2006 Nov-Dec;82(6):409–410. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Macdonald GM, Higgins JP, Ramchandani P. Cognitive-behavioural interventions for children who have been sexually abused. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001930.pub2. CD001930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Stallard P. Psychological interventions for post-traumatic reactions in children and young people: a review of randomised controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006 Nov;26(7):895–911. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Finkelhor D, Berliner L. Research on the treatment of sexually abused children: a review and recommendations. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995 Nov;34(11):1408–1423. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199511000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Laney C, Loftus EF. Traumatic memories are not necessarily accurate memories. Can J Psychiatry. 2005 Nov;50(13):823–828. doi: 10.1177/070674370505001303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]