Abstract

The prevalence of stroke worldwide and the paucity of effective therapies have triggered interest in the use of transcranial ultrasound as an adjuvant to thrombolytic therapy. Previous studies have shown that 120-kHz ultrasound enhanced thrombolysis and allowed efficient penetration through the temporal bone. The objective of our study was to develop an accurate finite-difference model of acoustic propagation through the skull based on computed tomography (CT) images. The computational approach, which neglected shear waves, was compared with a simple analytical model including shear waves. Acoustic pressure fields from a two-element annular array (120 kHz and 60 kHz) were acquired in vitro in four human skulls. Simulations were performed using registered CT scans and a source term determined by acoustic holography. Mean errors below 14% were found between simulated pressure fields and corresponding measurements. Intracranial peak pressures were systematically underestimated and reflections from the contralateral bone were overestimated. Determination of the acoustic impedance of the bone from the CT images was the likely source of error. High correlation between predictions and measurements (R2=0.93 and R2=0.88 for transmitted and reflected waves amplitude, respectively) demonstrated that this model is suitable for quantitative estimation of acoustic fields generated during 40-200 kHz ultrasound-enhanced ischemic stroke treatment.

Keywords: Transcranial ultrasound, Finite-difference simulation, Computed Tomography, Thrombolysis

1. Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of death and disability in the world. Contemporary estimates of occurrence are about 795,000 strokes per year in the United States of America (Roger et al 2012). Approximately 80% of these strokes entail interruption of the blood supply, classified as acute ischemic stroke (Broderick et al 1998, Williams et al 1999). Multiple studies have confirmed that clinical outcomes in acute ischemic stroke strongly depend on how rapidly occluded cerebral arteries are reperfused (Hacke et al 2004, Lansberg et al 2009, Khatri et al 2009). Intravenous injection of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) is an established treatment, supported by randomized clinical trials (The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group 1995, Kwiatkowski et al 1999, Adams et al 2007). Ultrasound is a promising adjuvant to thrombolysis with rtPA. The efficiency of ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis (UET) has been demonstrated by several groups and recent advances in this field are reviewed by Holland et al (2011) and Meairs et al (2012). Although the mechanisms involved in UET are not fully understood, cavitation is thought to play an important role. In vitro studies demonstrated that a higher thrombolytic efficacy was obtained with a sustained stable cavitation regime than with an inertial cavitation regime or no cavitation activity (Datta et al 2006, 2008). Therefore, a narrow acoustic pressure range is required in situ to maintain a sustainable cavitation regime maximizing ultrasound-enhanced rtPA thrombolysis. The upper limit of this range is of particular concern as high acoustic pressures can lead to negative bioeffects (Schneider et al 2006). A high occurrence of severe intra-cerebral hemorrhages was reported during the Transcranial Low-Frequency Ultrasound-Mediated Thrombolysis in Brain Ischemia (TRUMBI) clinical study (Daffertshofer et al 2005). Pressure levels above the inertial cavitation threshold with potential harmful effects were suspected retrospectively (Wang, Z et al 2008b, Baron et al 2009).

Generating the ultrasound field required for safe and efficient UET through the skull is challenging. The ultrasound waves are partially reflected, attenuated and distorted when they propagate through the skull. Variation of the geometry and the mechanical properties of skull between subjects may induce a significant variability in transcranial ultrasound fields. Insufficient temporal bone window prevents adequate 2-MHz transcranial Doppler (TCD) diagnostics in about 20% of patients (Wijnhoud et al 2008). In a clinical study, the application of 2-MHz TCD improved rtPA thrombolysis (Alexandrov 2004). However, the efficiency was likely limited for patients with an insufficient temporal bone window. Ultrasound frequencies in the 20-800 kHz range were chosen in several recent UET studies (Daffertshofer et al 2005, Schneider et al 2006, Datta et al 2006, Wang, Z et al 2008, Wang, B et al 2008, Shimizu et al 2012). This frequency range allows efficient penetration through the skull (Fry and Barger 1978, Ammi et al 2008). This frequency range also promotes mechanical effects and avoids thermal effects, which is preferable for UET. Techniques for precise transcranial spatial targeting with transducer arrays have been developed (Hynynen and Sun 1999, Clement and Hynynen 2002, Aubry et al 2003, Haworth et al 2008). However, these techniques may not be necessary for the emergency treatment of ischemic stroke. In particular, standard non-contrast CT images are typically acquired to facilitate diagnosis and management of stroke patients (Adams et al 2007). Once the side of the brain containing the thrombus is established, an unfocused broad beam which encompasses the occluded circulation may suffice for UET. Therefore, collimated ultrasound beams have been chosen as an alternative approach. However, sub-megahertz unfocused ultrasound insonation may induce a strong interference pattern inside the skull, potentially causing harmful effects (Baron et al 2009).

Transcranial ultrasound numerical models using CT images of the skulls as input have been used for a wide range of purposes (Aubry et al 2003, Yin and Hynynen 2005, Baron et al 2009, Deffieux and Konofagou 2010, Pulkkinen et al 2011, Pinton et al 2012b). A computational model using clinical CT-scans can be applied to the study of acoustic fields generated during UET. Simulations of ultrasound fields generated during 300-kHz UET were performed using a single head CT scan (Baron et al 2009, Pinton et al 2012b). However, the lack of quantitative validation of transcranial propagation numerical models limits their application to qualitative analysis. An experimentally validated, accurate numerical model would be valuable to predict acoustic fields produced during UET in humans. The purpose of this study is to develop a numerical model for the prediction of acoustic propagation in the skull from CT scans, and to evaluate quantitatively its accuracy. The model is first validated against a single-plate analytical model. Registered simulations are also compared with in vitro experimental measurements in four human skulls. Previous work has shown significant thrombolytic enhancement at 120 kHz (Datta et al 2006, 2008, Hitchcock et al 2011). This frequency also allows high transmission through the skull (about 80%) and potentially low inter-patient variability (Ammi et al 2008). In this study, experiments with120-kHz ultrasound exposures of the temporal bone, relevant for UET, were conducted to validate the numerical model. Measurements of the intracranial field from 60-kHz insonification through the temporal bone and 120-kHz insonification through the parietal bone were also performed to extend the validation.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Transcranial ultrasound finite-difference model

Following the method described by Blanch (1995), the wave propagation through both skull and water was modeled by a strain-stress relation, the momentum conservation equation, and a memory equation:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where p is the acoustic pressure, v the particle velocity, M the longitudinal modulus, ρ the density, s a source term, and r a memory variable. A single relaxation mechanism with stress and strain relaxation times τζ and τε was used to model frequency-dependent attenuation. Shear wave transmission was neglected, as the transducer was relatively parallel to the bone. Nonlinear propagation was not taken into account as low peak pressure amplitudes (below 1 MPa) are generally used in UET studies (for example, Datta et al 2006, 2008, Hitchcock et al 2011).

These equations were solved using a staggered-grid finite-difference scheme with second and fourth order approximation for time derivatives and spatial derivatives, respectively (Blanch 1995, Bohlen 2002). The spatial step of finite-difference grid, h, and the simulation time step, Δt, were determined according to the criteria given by Blanch (1995), in order to ensure low numerical dispersion and stability:

| (4) |

| (5) |

where fmax is the maximum frequency, cmin and cmax are the minimum and maximum speed of sound in the computational grid, respectively. For this study fmax was set to 400 kHz, cmin to 1490 m/s, and cmax to 4000 m/s. Thus a 0.6 mm grid step and a 74 ns time step were employed. The boundaries of the computational domain were coated with perfectly matched layers, using the method described by Chew and Weedon (1994). This finite-difference method was implemented in Matlab (R2011b, Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) and in C using multi-threading in order to take advantage of multi-core processors. The simulations were run on a PC computer with 10 GB memory and a 3.4-GHz processor with four cores.

Density maps were estimated from CT images expressed in Hounsfield units (HU) by applying a linear relation obtained from the measured HU of air and water and their known densities (Connor et al 2002). The speed of sound and acoustic attenuation maps were determined from the density maps using the relations established experimentally by Pichardo et al (2011). These relations between speed of sound, attenuation and density, expressed as spline coefficients, were applied to the density maps obtained from CT images. Data measured at 270 kHz, the lowest frequency available in Pichardo et al (2011), were used. Furthermore, a linear frequency-dependence of attenuation was assumed over the 0-270 kHz frequency range. A speed of sound of 1490 m/s, and a null value for attenuation were assigned to water. The propagation speed, c, and the attenuation,, for a harmonic wave with angular frequency ω can be determined from equations 1, 2 and 3:

| (6) |

| (7) |

The parameters M, τσ and τσ used in the model (equations 1, 2 and 3) were estimated from the speed of sound, density and attenuation maps for each voxel. Following a method similar to the one described by Bohlen (2002), τσ and τε were found by minimizing the mean squared error between α evaluated with equation 7 and the targeted frequency-dependent attenuation. The longitudinal modulus, M, was determined using equation 6, in order to obtain the targeted speed of sound at the insonification center frequency.

2.2. Single plate analytical model

The finite-difference model and the CT data preprocessing were first validated using the one-dimensional analytical ultrasound model derived by Folds (1977). This model was implemented in order to compute the transmission and reflection coefficients of a single bone plate in water insonified by a plane harmonic wave with oblique incidence. Phantom CT images of 20 × 20 cm2 thin homogeneous bone-mimicking plates were generated. The value of the voxels on the boundary of the plate was proportional to the bone to water volume ratio within these voxels, to mimic the partial volume effect inherent to CT scans. The synthetic CT image was transformed to attenuation and speed of sound maps, using the method based on Pichardo et al (2011), described previously. A uniform piston source (20 cm diameter) with a Ricker wavelet velocity excitation (-6dB bandwidth: 60-220 kHz) was modeled. The lateral dimensions of the plate and the source were chosen in order to satisfy the plane wave assumption required by the analytical model. The transmitted and reflected beam waveforms were computed using the finite difference model. Transmission and reflection coefficients were obtained by dividing the Fourier-transformed transmitted and reflected waveforms by the spectrum of the excitation wavelet.

For each finite-difference simulation, corresponding transmission and reflection coefficients were computed with the analytical model, using the same plate thickness, density, speed of sound, and acoustic attenuation. The analytic computations were performed twice: shear wave conversion in the plate was first neglected, and then included. The propagation speed of shear waves in the bone plate was set to 1500 m/s, and a 75 Np/m shear-wave attenuation at 120 kHz was extrapolated from the measurements in skull bone of White et al (2006). The coefficients of transmission and reflection were computed for frequencies ranging from 0 to 240 kHz.

Finite-difference simulations and corresponding analytic model computations were conducted for several bone-mimicking plates. Thicknesses ranged from 0.5 mm to 7 mm, and a 20° angle of incidence was chosen. To cover several types of bone (trabecular and cortical), plates with three densities were considered: 1500 kg/m3, 1875 kg/m3 and 2250 kg/m3. Conversion of these densities to speeds of sound gave: 1939 m/s, 2264 m/s and 2813 m/s, respectively. Similarly, the corresponding attenuations at 120 kHz were: 27 Np/m, 8 Np/m and 24 Np/m.

2.3. Skulls preparation and CT acquisition

Four desiccated human skulls were obtained from the Body Donation Program of the University of Cincinnati. Skullcaps were removed to provide direct access for hydrophone measurements. Six fiducial markers (polytetrafluoroethylene, approximate dimensions: 5×5×1 mm3) were affixed to each skull with silicone rubber. The skulls were mounted on a frame and immersed in a polypropylene container full of deionized water. The container was exposed to vacuum for 24 hours (-0.9 bar). CT scans of the skulls in their container were obtained with a LightSpeed Pro 16 scanner (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St Giles, UK). Skulls were oriented to obtain axial imaging parallel to the orbitomeatal plane. The field of view was chosen to include the complete skull and all fiducials. Scan parameters consisted of a slice thickness of 1.25 mm at 0.625 mm intervals and a 0.5 × 0.5 mm2 spatial resolution. The tube voltage was 120 KVp and the maximum X-ray tube current was set to maximize the signal to noise ratio (from 600 to 700 mA). The standard bone reconstruction kernel of the CT scanner was applied.

2.4. Ultrasound field measurements in skulls

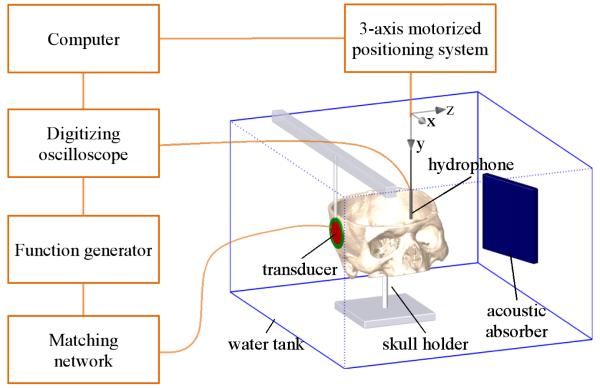

The degassed skulls were mounted in a 97 × 57 × 54 cm3 acrylic tank filled with deionized, degassed water (22°C) for ultrasound field measurements. The experimental setup is depicted in figure 1. A flat cylindrical two-element piezocomposite transducer designed for UET was used to insonify the skull (Sonic Concepts Inc., Seattle, WA, USA). The central element, designed for therapeutic emission, had a 30 mm active diameter. The center frequency was 120 kHz, the −12 dB bandwidth was 60-200 kHz, and the focal distance in water was 18 mm. The annular element, designed for subharmonic passive cavitation detection but used for transmission here, had a nominal frequency of 60 kHz and a −12 dB bandwidth from 40 kHz to 95 kHz. Its inner and outer diameters were 31 mm and 40 mm, respectively.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup.

Intracranial acoustic field measurements were acquired using a calibrated hydrophone with a 10-800 kHz nominal frequency range (TC4038, Reson, Goleta, CA, USA) mounted on a three-axis computer-controlled positioning system (Velmex NF90 Series, Velmex, Inc. Bloomfield, NY, USA). Fields obtained through two locations of the skulls were acquired. First, the skull was positioned with the transducer directed toward the temporal bone and the anterior clinoid processes. This region corresponds to the origin of the middle cerebral artery, a probable site for clot in acute ischemic stroke (Ammi et al 2008). In order to evaluate ultrasound penetration through bone thicker than the temporal bone, a second location in the parietal bone was used. In both cases the skull-transducer distance was approximately 1 cm. The temporal and the parietal locations are illustrated in figure 2. An acoustic absorber was placed in the tank opposite the transducer, to minimize reflections.

Figure 2.

Registered skull CT data, transducer, and measurement zone. The locations of the fiducial markers are marked by a ‘o’. The box in the skull represents the measurement zone. The dotted-line frame indicates the extents of the computational domain. Two examples are shown: (a) the transducer is positioned at the temporal location; (b) the transducer is at the parietal location.

Ultrasound fields generated by the 120-kHz transducer element of the transducer were acquired for both temporal and parietal locations. The transducer was excited with a single sinusoidal cycle at 120-kHz with a signal generator (model 33250A, Agilent Technology, Palo Alto, CA, USA) through a custom electrical matching network. The signal generator was set to 10 V peak to peak. No amplifier was necessary as the study was conducted in a low amplitude, linear regime. Ultrasound fields generated by the annular element excited with one sinusoidal cycle at 60 kHz were acquired for the temporal location only. For each skull location, the hydrophone was moved such that its tip touched the center of the fiducial markers in order to record their coordinates. The ultrasound fields were acquired in a large region from the ipsilateral to the contralateral bones (figure 2). The scanning steps along x, y and z axes (shown in figure 1) were 2.5 mm, 5-9 mm and 5 mm, respectively. At each measurement position, the hydrophone signal was digitized using a 2-MHz sampling frequency (LT 584 oscilloscope, Lecroy, Chestnut Ridge, NY, USA) and transferred to a computer. After each experiment, the skull was removed, and the ultrasound field in water was acquired in the same conditions. An additional free-field map was acquired in a 16×16 cm2 zone along the xy plane, at a distance of 4 cm from the transducer. This field was needed to build the source term of the numerical model, as described below.

2.5. Simulations

For each acoustic field measurement, a corresponding simulation was performed using the finite-difference model. The positions of the fiducial markers were determined in the CT image. The rigid transformation minimizing the distance with the corresponding positions measured in the computer-controlled positioning system was applied to the acoustic parameter maps obtained from CT images. During this registration process, the acoustic parameter maps were also resampled at the computational grid step size (0.6 mm).

The source term (s, in equation 2) was determined using the xy plane free-field acoustic pressure measurement. The distance between the transducer and the measurement plane was estimated from the acoustic time of flight and the temperature in the water (22°C). The orientation of the transducer surface was assessed using the phase information. The transient acoustic holography method (Sapozhnikov et al 2006) was applied in order to reconstruct the time-domain velocity distribution on the transducer surface. The reconstructed velocity source was used in the finite-difference model. Therefore, the source was modeled as a transparent transducer (with no reflection on its surface), assuming that the response of the transducer, measured in water, is not affected by the presence of the skull.

The simulated pressure fields were compared to the corresponding experimental hydrophone measurements. The relative prediction error in peak amplitude was defined as:

| (8) |

where psimu(x,y,z,t) is the simulated acoustic pressure, and pmeas(x,y,z,t) is the corresponding pressure measurement. For each experiment, the average and standard deviation of the relative error in the measurement volume were evaluated. To supplement this global error measurement, two points of interest of the acoustic field were considered. The first point of interest was the position of the measured peak free-field pressure. The second point of interest was the position of the peak amplitude measured in the beam reflected on the contralateral bone. To determine the position of this point, the peak pressure amplitude measured for t > tout was localized, where tout is the time needed for the transmitted pulse to traverse the measurement zone. Simulated peak acoustic pressures were compared with measurements at these two locations for all the experiments.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison between the finite difference model and the analytical model

The transmission and reflection coefficients obtained with the finite-difference model were compared with the corresponding analytic calculations (figure 3). For all the thicknesses, material parameters, and frequencies that were considered, the transmission and reflection coefficients estimated by the finite-difference model were in very good agreement with those obtained with the analytical model with no shear waves (root mean square errors 0.7% and 1.2% for transmission and reflection, respectively). Discrepancies were larger when comparing the finite-difference model results with the analytical model taking into account shear waves (root mean square errors 2.1% and 4.6%). The discrepancies tended to increase with plate thickness and the frequency.

Figure 3.

Transmission and reflection coefficients for a solid plate immersed in water and insonified by a plane wave with a 20° angle of incidence. The transmission coefficient (a), and the reflection coefficient (b) at 120 kHz are shown for various material properties as a function of plate thickness. The transmission and reflection coefficient as functions of frequency (c) are shown for a 4 mm thick plate, with mass density 1875 kg/m3. The transmission and reflection coefficient were estimated using: the analytical model without shear waves ‘- -’, the analytical model with shear waves ‘…’, and the finite difference model ‘–’.

3.2. Skull CT images

For all the skulls, the average error in the fiducial marker positions after registration was below 0.9 mm. The position and orientation of the transducer in the experimental coordinate system was estimated from free-field measurements. Figure 2 shows the CT data from a skull and the transducer registered in the computational coordinate system. Bone thickness and mean density (determined from the CT data) were estimated along the acoustic axis of the transducer (table 1). The angle between the acoustic axis of the transducer and the normal to the outer surface of the bone was also estimated and is reported in table 1.

Table 1.

Bone thickness, mean mass density and angle of incidence estimated along the acoustic axis of the transducer from the CT images.

| Transducer location |

Skull | Bone thickness mm |

Mean density kg/m3 |

Incidence angle degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal | 1 | 3.5 | 2216 | 14 |

| 2 | 1.7 | 2115 | 20 | |

| 3 | 3 | 1685 | 24 | |

| 4 | 3.7 | 1923 | 23 | |

|

| ||||

| Parietal | 1 | 3.5 | 2356 | 8 |

| 2 | 5.1 | 2228 | 17 | |

| 3 | 6.3 | 1658 | 15 | |

| 4 | 6 | 2127 | 17 | |

3.3. Free field measurements and acoustic holography method

Using the source term obtained with the acoustic holography technique, full three-dimensional time-dependent acoustic pressure fields in water were simulated (figure 4). The simulations were compared with free-field measurements that were acquired after each experiment with the skull removed from the tank. The error in the predicted pressure amplitude averaged over the scanning zone was below 1.5% (standard deviation 1.6%) for all experiments.

Figure 4.

Ultrasound field in water for the two elements of the transducer excited with 1 cycle sine pulses.

3.4. Acoustic fields in the skull

The acoustic fields in the four skulls, for both locations (parietal and temporal bone) and using both the 60-kHz and the 120-kHz elements of the transducer were simulated and compared with the corresponding measurements (figure 5). In addition to xz maps of the peak pressures, measured and simulated acoustic waveforms are shown for the two points of interest: the position of the maximum peak pressure measured in the free-field (marked with an ‘o’ in figure 5) and in the reflected beam (marked with an ‘x’). For all experiments, both measurements and simulations indicated that the spatial shift of the maximum of pressure amplitude induced by the skull was below 2.5 mm (the scanning step). An acoustic reflection on the contralateral bone was observed for all the skulls in both predicted and measured fields. In the first example shown in figure 5 (skull 1, 120 kHz, temporal bone), a first reflection (from the contralateral bone) was visible from 100 μs to 150 μs, as well as second and third reflections after 250 μs (from ipsilateral and contralateral bones, respectively). A movie showing the measured and simulated propagation of the ultrasound pulse for this skull is available as a supplementary file. In the second example (skull 2, 120 kHz, parietal bone), both simulated and measured time-waveforms showed a weak reflection after 90 μs. In the third example (skull 3, 60 kHz, temporal bone), the predicted reflection (after 120 μs), was overestimated in amplitude (42%), and a −1.8 μs time lag was observed. In the last example (skull 4, 120 kHz temporal bone), the simulated peak pressure field and waveform shapes are in good agreement with the hydrophone measurements.

Figure 5.

Acoustic field measurements and corresponding simulations for four representative experiments. The peak pressure spatial distributions are normalized by the peak free field amplitude in the measurement zone (visualized by a rectangle). The red line indicates the location of the transducer. The position of the peak pressure amplitude measured in the skull is marked by an ‘o’. The position of the peak amplitude measured in the reflected wave is marked by an ‘x’. The pressure waveforms measured and simulated at these two locations are shown on the right hand side.

The mean of the error defined in equation 8 and its standard deviation were evaluated for all the experiments and are reported in table 2. The predicted pressure was generally underestimated (negative mean errors). The degree of underestimation depended on the frequency and the bone location. Averaged over the 4 skulls for each location and frequency, the mean error was 4% for temporal bone at 120 kHz, 9% for parietal bone at 120 kHz, and 1% for temporal bone at 60 kHz. The standard deviation of the error was consistently around 5% for all the experiments.

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation of the relative error in predicted peak amplitude for all the experiments.

| Frequency kHz |

Location | Skull | Error in pressure amplitude Field in skull |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean % | Std. % | |||

| 120 | Temporal | 1 | −7.6 | 5.4 |

| 2 | −3.4 | 5.6 | ||

| 3 | −3.5 | 6.4 | ||

| 4 | −0.9 | 3.6 | ||

|

| ||||

| 120 | Parietal | 1 | −5.8 | 4.6 |

| 2 | −9.2 | 4.9 | ||

| 3 | −8.1 | 2.7 | ||

| 4 | −13.6 | 6.0 | ||

|

| ||||

| 60 | Temporal | 1 | −2.3 | 4.1 |

| 2 | 0.9 | 3.2 | ||

| 3 | −0.5 | 4.4 | ||

| 4 | 1.0 | 4.8 | ||

3.5. Amplitude of the transmitted and reflected waves

The maximum pressure amplitudes at the two points of interest (peak amplitudes measured in the transmitted beam and in the reflected beam) were extracted for all the hydrophone measurements and the corresponding simulations. Pressure amplitudes measured and predicted at these points were compared. In order to analyze all the experiments together, the acoustic pressure amplitudes were normalized. The maximum transmitted pressures were divided by the free field pressures at the same location. Similarly, the maximum amplitudes in the reflected beam were divided by the peak amplitude in the transmitted beam. The simulated relative transmitted and reflected pressure amplitudes are shown as a function of corresponding measurements in figure 6. For both transmission and reflection, a curve of the form y-1-1=a(x-1-1) was fitted to the data in a least-squares sense. The form of this equation was chosen because it describes the deviation of the data from a line designating perfect agreement between the simulated and measured data (y=x). This form is relevant for both the transmission and reflection cases: a=1 corresponds to the ideal case where predictions and measurements are equal, a>1 indicates underestimation, and a<1 overestimation. The correlation coefficient was 0.94 for the maximum transmitted amplitude (p<0.0001), and 0.88 for the relative reflection amplitude (p<0.0001). In all the experiments, the maximum pressure amplitude in the skull was underestimated (a=1.73, 95% confidence interval: 1.54-1.92), as shown in figure 6a. Conversely, the ratio between the peak amplitude in the reflected beam and the maximum amplitude in the skull was overestimated by the simulations (a=0.63, 95% confidence interval: 0.52-0.74), as seen in figure 6b.

Figure 6.

Simulated relative pressure amplitude as a function of corresponding measurements, (a) at the position of the maximum amplitude in the skull, (b) at the position of the maximum amplitude of the wave reflected by the contra-lateral bone. The ideal case is represented by the dotted line (simulation=measurement). The solid curve is fitted to the data points in a least-squares sense, and the grey dashed lines show the 95% confidence interval.

The time lags between the simulated and measured pressure waveforms at the location of the peak transmitted amplitude were estimated using a cross-correlation algorithm. At 120 kHz, the simulated signal preceded the measured signal for seven cases out of eight. The time lags ranged from −270 ns to 100 ns for the temporal bone transducer location, and from −610 ns to −350 ns for the parietal bone location.

4. Discussion

Comparisons with the analytical model confirmed that the finite-difference scheme could accurately model bone-mimicking plates insonified with 0-240 kHz ultrasound at a 20° angle of incidence. Although the spatial grid step (0.6 mm) was relatively large compared to the thickness of the plates (0.5 mm to 7 mm), no artifact due to discretization or partial volume effect was observed. Transmission and reflection coefficients were in very good agreement when shear waves were neglected in the analytical model. Larger but moderate discrepancies were found when shear waves were included in the analytical model. At 120 kHz, for bone plate thicknesses from 1.7 mm to 3.7 mm (temporal bone thicknesses in this study), the relative error was below 4.1% for the transmission coefficient and below 9.7 % for the reflection coefficient. These results suggest that for the experimental conditions of this study (incidence angle below 24°, 40-200 kHz frequency range covered by the transducer elements), the shear waves could be neglected in the finite-difference model with limited error. Taking into account shear wave propagation is feasible with the finite-difference scheme chosen in this study (Bohlen 2002, Pinton et al 2012a). Although accuracy could be enhanced, modeling shear waves would increase the computational cost substantially, as more variables and a finer gird spacing are required (Vossen et al 2002).

The transient acoustic holography method was successfully applied to build the source used in finite-difference simulations. The accuracy of the free-field predictions were verified against hydrophone measurements of the field. The velocity source was applied in water, neglecting the reflections on the transducer surface. Such reflections were not experimentally observed during the hydrophone measurements in skulls.

The four skulls and the two transducer locations used in this study covered a wide range of densities (1658 kg/m3 to 2228 kg/m3) and thicknesses (1.7-6.3 mm). For all the experiments, a good agreement between simulations and hydrophone measurements of intracranial acoustic fields was found (mean error below 14%). Spatial peak pressure distributions showed that both transmission through the proximal temporal bone and reflection on the contralateral bone were predicted correctly. The waveform shapes obtained by simulation were also in agreement with hydrophone measurements. Second and third reflections inside the skull were simulated and confirmed by measurements. In some experiments, relatively large time lags (<1.8 μs) between the measured and simulated reflected pulses (e.g. skull 3 shown in figure 5) may have been caused by inaccurate CT image registration, which can also induce error in the predicted peak amplitude.

Quantitative error estimation of the simulated pressure amplitude indicated an overall underestimation in the predictions, which depended on the frequency and the skull thickness. Additional information was supplied by the analysis of the maximum pressures in the transmitted and reflected beams. The simulated transmitted beam amplitude was underestimated in all the experiments whereas the relative reflected beam amplitude was overestimated. This error was likely due to a systematically overestimated acoustic impedance of the bone. For most of the experiments, the simulated waveforms were found to precede the measured waveforms by up to 610 ns after propagation through the bone. Therefore, the speed of sound in bone was likely overestimated. A speed of sound overestimation of 17% on average (standard deviation 12%) can be estimated from the time lags between simulations and measurements, by considering that the bone has homogeneous thickness, speed of sound and density.

The acoustic parameter maps were obtained from CT images using the relations determined by Pichardo et al (2011). Other methods for estimating acoustic parameters and density from CT data have been used (Aubry et al 2003, Deffieux and Konofagou 2010, Pinton et al 2011). However, these methods require an a priori estimate of the maximum density and speed of sound in bone. The density-speed of sound and density-attenuation relations established by Pichardo et al (2011) relied on empirical measurements performed in several skulls and were in good agreement with similar relations determined by Connor et al (2002). Therefore, these robustly established relations required no preliminary assumption and were applied in our study. The frequency range investigated here (40-200 kHz) was below 270 kHz, the lowest frequency addressed by Pichardo et al (2011). Dispersion may be a cause of the inaccurate estimation of speed of sound. Moreover, desiccated skulls were used in the experiments presented here, whereas skulls fixed in a formalin buffer were used by Pichardo et al (2011). Fry and Barger (1978) showed that the acoustic properties of bone are maintained in time by tissue fixation. White et al (2007) showed in a porcine skull model that the desiccation process leads to a higher speed of sound at 1 MHz. However, the speed of sound increase due to desiccation found by them (2.3 %) is too small to fully explain the transmitted pressure underestimation. The standard deviation of the error in prediction (table 2) was around 5 % for all experiments. This root mean square error characterized the accuracy of spatial peak pressure distribution without systematic error. This suggested that most of the error in pressure amplitude prediction was due to the bias in the estimation of bone acoustic parameters from CT scans. To reduce this error, relations between speed of sound, attenuation, density and CT Hounsfield unit values could be established in our frequency range (40-200 kHz), using the methods described by Connor et al (2002) and Pichardo et al (2011). Despite this moderate systematic error estimation, high correlation coefficients between predictions and measurements were found for both reflected (R2=0.88) and transmitted (R2=0.93) amplitudes. Thus the comparison of simulated ultrasound fields in several skulls of different geometries and material properties is relevant.

The ultrasound beam transmitted through each skull was weakly distorted both in terms of spatial distribution and waveform shape, in comparison to the free field. For 120-kHz transmission through the temporal bone, the pressure reduction ranged from 15% to 33% and the shift in peak pressure position was below 2.5 mm. For continuous 120-kHz ultrasound transmission through the temporal bone, Ammi et al (2008) reported a larger variability in intracranial acoustic pressure (from 1% to 45% reduction compared to free field) and up to 22 mm shifts in the position of the peak pressure. These larger distortions were likely due to acoustic interference in the skull. As single cycle excitations were used in our study, interference patterns were limited to a small zone near the contralateral bone. Nevertheless, important reflections depending on the geometry and material properties of the skull were observed by simulation and measurement. The maximum amplitude measured in the reflected beam ranged from 18% to 67% of the peak amplitude in the transmitted beam. More than one reflection was observed in some experiments (for example skull 1 in figure 5). Only one reflection was visible in other experiments because the second reflection was probably directed outside the measurement zone (for example skull 4 in figure 1). With longer acoustic pulses or continuous excitation, the reflected waves would combine with the transmitted wave and cause interferences. An example of a continuous wave pressure amplitude field deduced from the simulation for skull 1 exposed to 120-kHz ultrasound through the temporal bone is given in figure 7. An interference pattern was clearly visible, similar to measurements by Ammi et al (2008) at the same frequency, or to simulations conducted with the TRUMBI trial parameters at 300 kHz (Baron et al 2009).

Figure 7.

Amplitude (in dB) of the 120 kHz component extracted from the pulsed wave simulation for skull 1, transmission through the temporal bone with the 120-kHz transducer element.

The model was validated for the 40-200 kHz frequency range covered by the two elements of the transducer. When frequency increases, larger attenuation and phase aberration are expected, and neglecting shear wave conversion in the bone may also cause more significant discrepancies (figure 3c). Therefore, the prediction accuracy may be decreased at higher frequencies. Deffieux and Konofagou (2010) found good agreement between finite-difference simulations and in vitro measurements in a human skull at 550 kHz and a primate skull at 800 kHz. However, a study comparing simulations and measurements in several skulls is needed to evaluate the quality of the predictions at these frequencies. The accuracy of the simulation of transcranial ultrasound fields obtained in this study can be seen as an advantage of the investigated frequency range (<200 kHz). Moreover a relatively coarse computational grid can be used, allowing fast full-skull simulations when shear-waves are neglected (20 to 90 minutes). This computational time can be further reduced by increasing the number of processors (Bohlen 2002). These relatively fast and accurate simulations can be used for design and validation steps of an ultrasound setup for UET, for which patient CT scans can be used retrospectively. Furthermore, diagnostic CT-scans of presenting patients can be utilized for assessing appropriate transducer excitation parameters before UET treatments. The simulation time is compatible with the 45 minutes maximum door to image interpretation time recommended for acute stroke patients (Adams et al 2007).

5. Conclusion

A finite difference model for the simulation of transcranial ultrasound based on CT scans was implemented. Comparisons with an analytical model showed shear wave conversion in the temporal bone can be neglected for the experimental conditions of this study (incidence angle below 24°, 40-200 kHz frequency range). Accurate predictions were obtained with a relatively coarse CT resolution (0.5 mm × 0.5 mm, slice thickness 1.25 mm) and computational grid step (0.6 mm) in comparison with the bone thickness (0.5 mm – 7 mm). Acoustic fields in 4 human skulls insonified with short 60-kHz and 120-kHz pulses were acquired to evaluate the accuracy of corresponding finite-difference simulations. Registered parameter maps obtained from CT scans and a source term determined by transient acoustic holography were used as the input of the model. Simulations were in good agreement with the measurements in terms of spatial distribution, waveform shapes, and peak pressure (mean error of prediction was less than 14%). The amplitude of the wave transmitted through the bone was consistently underestimated, and the amplitude of the reflected wave was overestimated. This error indicated an overall overestimation of bone acoustic impedance. The relations used to assess acoustic properties maps from CT data were determined by Pichardo et al (2011) for formalin-fixed skulls at 270 kHz, whereas we used desiccated skulls in the 40-200 kHz frequency range. This difference may explain this systematic bias. High correlation coefficients were found between simulations and measurements of pressure amplitudes of the waves transmitted through the ipsilateral bone (R2=0.94) and the reflection on the contralateral bone (R2=0.88). These results show that it is feasible to use a finite-difference model based on head CT scans to quantitatively evaluate ultrasound fields produced in the skull during 40-200 kHz UET.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Bruce Giffin from the Body Donation Program of the University of Cincinnati for providing the skull specimens. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Health (number R01 NS047603).

Footnotes

PACS numbers: 43.20.Gp, 43.80.Ev, 43.60.Sx, 87.59.bd

References

- Adams HP, Zoppo GD, Alberts MJ, Bhatt DL, BrassL FurlanA, Grubb RL, Higashida RT, Jauch EC, Kidwell C, Lyden PD, Morgenstern LB, Qureshi AI, Rosenwasser RH, Scott PA, Wijdicks EFM. Guidelines for the Early Management of Adults With Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2007;38:1655–711. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.181486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov AV. Ultrasound identification and lysis of clots. Stroke. 2004;35:2722–5. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000143321.37482.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammi AY, Mast TD, Huang I-H, Abruzzo TA, Coussios C-C, Shaw GJ, Holland CK. Characterization of Ultrasound Propagation Through Ex-vivo Human Temporal Bone. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2008;34:1578–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubry JF, Tanter M, Pernot M, Thomas J-L, Fink M. Experimental demonstration of noninvasive transskull adaptive focusing based on prior computed tomography scans. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2003;113:84. doi: 10.1121/1.1529663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron C, Aubry J-F, Tanter M, Meairs S, Fink M. Simulation of Intracranial Acoustic Fields in Clinical Trials of Sonothrombolysis. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2009;35:1148–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanch JO. A study of viscous effects in seismic modeling, imaging, and inversion: Methodology, computational aspects, and sensitivity. Rice University; 1995. Online: http://hdl.handle.net/1911/16968. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlen T. Parallel 3-D viscoelastic finite difference seismic modelling. Computers & Geosciences. 2002;28:887–99. [Google Scholar]

- Broderick J, Brott T, Kothari R, Miller R, Khoury J, Pancioli A, Gebel J, Mills D, Minneci L, Shukla R. The Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Study: preliminary first-ever and total incidence rates of stroke among blacks. Stroke. 1998;29:415–21. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.2.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew WC, Weedon WH. A 3D perfectly matched medium from modified maxwell’s equations with stretched coordinates. Microwave and Optical Technology Letters. 1994;7:599–604. [Google Scholar]

- Clement GT, Hynynen K. A non-invasive method for focusing ultrasound through the human skull. Phys Med Biol. 2002;47:1219–36. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/47/8/301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor CW, Clement GT, Hynynen K. A unified model for the speed of sound in cranial bone based on genetic algorithm optimization. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2002;47:3925–44. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/47/22/302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daffertshofer M, Gass A, Ringleb P, Sitzer M, Sliwka U, Els T, Sedlaczek O, Koroshetz WJ, Hennerici MG. Transcranial Low-Frequency Ultrasound-Mediated Thrombolysis in Brain Ischemia. Stroke. 2005;36:1441–1446. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000170707.86793.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Coussios C-C, Ammi AY, Mast TD, de Courten-Myers GM, Holland CK. Ultrasound-enhanced thrombolysis using Definity® as a cavitation nucleation agent. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:1421–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Coussios C-C, McAdory LE, Tan J, Porter T, De Courten-Myers G, Holland CK. Correlation of cavitation with ultrasound enhancement of thrombolysis. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2006;32:1257–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deffieux T, Konofagou EE. Numerical study of a simple transcranial focused ultrasound system applied to blood-brain barrier opening. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control. 2010;57:2637–53. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2010.1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folds DL. Transmission and reflection of ultrasonic waves in layered media. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1977;62:1102. [Google Scholar]

- Fry FJ, Barger JE. Acoustical properties of the human skull. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1978;63:1576. doi: 10.1121/1.381852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacke W, Donnan G, Fieschi C, Kaste M, von Kummer R, Broderick JP, Brott T, Frankel M, Grotta JC, Haley EC, Jr, Kwiatkowski T, Levine SR, Lewandowski C, Lu M, Lyden P, Marler JR, Patel S, Tilley BC, Albers G, Bluhmki E, Wilhelm M, Hamilton S. Association of outcome with early stroke treatment: pooled analysis of ATLANTIS, ECASS, and NINDS rt-PA stroke trials. Lancet. 2004;363:768–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15692-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth KJ, Fowlkes JB, Carson PL, Kripfgans OD. Towards aberration correction of transcranial ultrasound using acoustic droplet vaporization. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:435–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock KE, Ivancevich NM, Haworth KJ, Caudell Stamper DN, Vela DC, Sutton JT, Pyne-Geithman GJ, Holland CK. Ultrasound-Enhanced rt-PA Thrombolysis in an ex vivo Porcine Carotid Artery Model. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2011;37:1240–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland CK, Shaw GJ, Datta S. Therapeutic Ultrasound: Mechanisms to Applications. Nova Science Publishers; Hauppauge, NY: 2011. Ultrasound-Enhanced Thrombolysis. [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen K, Sun J. Trans-skull ultrasound therapy: the feasibility of using image-derived skull thickness information to correct the phase distortion. Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control, IEEE Transactions on. 1999;46:752–755. doi: 10.1109/58.764862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri P, Abruzzo T, Yeatts SD, Nichols C, Broderick JP, Tomsick TA. Good clinical outcome after ischemic stroke with successful revascularization is time-dependent. Neurology. 2009;73:1066–72. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b9c847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski TG, Libman RB, Frankel M, Tilley BC, Morgenstern LB, Lu M, Broderick JP, Lewandowski CA, Marler JR, Levine SR, Brott T, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator Stroke Study Group Effects of tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke at one year. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340:1781–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906103402302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansberg MG, Schrooten M, Bluhmki E, Thijs VN, Saver JL. Treatment time-specific number needed to treat estimates for tissue plasminogen activator therapy in acute stroke based on shifts over the entire range of the modified Rankin Scale. Stroke. 2009;40:2079–84. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.540708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meairs S, Alonso A, Hennerici MG. Progress in Sonothrombolysis for the Treatment of Stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:1706–10. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.636332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichardo S, Sin VW, Hynynen K. Multi-frequency characterization of the speed of sound and attenuation coefficient for longitudinal transmission of freshly excised human skulls. Phys Med Biol. 2011;56:219–50. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/1/014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinton G, Aubry J-F, Bossy E, Muller M, Pernot M, Tanter M. Attenuation, scattering, and absorption of ultrasound in the skull bone. Medical Physics. 2012a;39:299. doi: 10.1118/1.3668316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinton G, Aubry J-F, Fink M, Tanter M. Effects of nonlinear ultrasound propagation on high intensity brain therapy. Medical Physics. 2011;38:1207. doi: 10.1118/1.3531553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinton G, Aubry J-F, Fink M, Tanter M. Numerical prediction of frequency dependent 3D maps of mechanical index thresholds in ultrasonic brain therapy. Med Phys. 2012b;39:455–67. doi: 10.1118/1.3670376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulkkinen A, Huang Y, Song J, Hynynen K. Simulations and measurements of transcranial low-frequency ultrasound therapy: skull-base heating and effective area of treatment. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2011;56:4661–83. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/15/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Soliman EZ, Sorlie PD, Sotoodehnia N, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2012 Update A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapozhnikov O, Ponomarev A, Smagin M. Transient acoustic holography for reconstructing the particle velocity of the surface of an acoustic transducer. Acoustical Physics. 2006;52:324–30. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider F, Gerriets T, Walberer M, Mueller C, Rolke R, Eicke BM, Bohl J, Kempski O, Kaps M, Bachmann G, Dieterich M, Nedelmann M. Brain edema and intracerebral necrosis caused by transcranial low-frequency 20-kHz ultrasound: a safety study in rats. Stroke. 2006;37:1301–6. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000217329.16739.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu J, Fukuda T, Abe T, Ogihara M, Kubota J, Sasaki A, Azuma T, Sasaki K, Shimizu K, Oishi T, Umemura S, Furuhata H. Ultrasound Safety with Midfrequency Transcranial Sonothrombolysis: Preliminary Study on Normal Macaca Monkey Brain. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2012;38:1040–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1581–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossen RV, Robertsson JOA, Chapman CH. Finite-Difference Modeling of Wave Propagation in a Fluid-Solid Configuration. Geophysics. 2002;67:618–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Wang L, Zhou X-B, Liu Y-M, Wang M, Qin H, Wang C-B, Liu J, Yu X-J, Zang W-J. Thrombolysis effect of a novel targeted microbubble with low-frequency ultrasound in vivo. Thromb. Haemost. 2008;100:356–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Moehring MA, Voie AH, Furuhata H. In Vitro Evaluation of Dual Mode Ultrasonic Thrombolysis Method for Transcranial Application with an Occlusive Thrombosis Model. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2008;34:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PJ, Clement GT, Hynynen K. Longitudinal and shear mode ultrasound propagation in human skull bone. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2006;32:1085–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PJ, Palchaudhuri S, Hynynen K, Clement GT. The Effects of Desiccation on Skull Bone Sound Speed in Porcine Models. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control. 2007;54:1708–10. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2007.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijnhoud AD, Franckena M, van der Lugt A, Koudstaal PJ, Dippel EDWJ. Inadequate acoustical temporal bone window in patients with a transient ischemic attack or minor stroke: role of skull thickness and bone density. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:923–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GR, Jiang JG, Matchar DB, Samsa GP. Incidence and Occurrence of Total (First-Ever and Recurrent) Stroke. Stroke. 1999;30:2523–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.12.2523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Hynynen K. A numerical study of transcranial focused ultrasound beam propagation at low frequency. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50:1821–36. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/8/013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.