Abstract

We investigated the association between yes/no sentence comprehension and dysfunction in anterior and posterior left-hemisphere cortical regions in acute stroke patients. More specifically, we manipulated whether questions were Nonreversible (e.g., Are limes sour?) or Reversible (e.g., Is a horse larger than a dog?) to investigate the regions associated with semantic and syntactic processing. In addition, we administered lexical tasks (i.e., Picture-Word Verification, Picture Naming) to help determine the extent to which deficits in sentence processing were related to deficits in lexical processing. We found that errors on the lexical tasks were associated with ischemia in posterior-temporal Brodmann Areas (BA 21, 22, 37) and inferior parietal regions (BA 39, 40). Nonreversible question comprehension was associated with volume of tissue dysfunction, while Reversible question comprehension was associated with posterior regions (BA 39, 40) as well as one anterior region (BA 6). We conclude that deficits in Nonreversible questions required extensive dysfunction that affected language processing across multiple levels, while Reversible question comprehension was associated with regions involved in semantics as well as working memory that indirectly influenced syntactic processing. Overall, this suggests that yes/no question comprehension relies on multiple regions and that the importance of certain regions increases in relation to semantic, phonological, and syntactic complexity.

Keywords: acute stroke, lesion analysis, sentence comprehension, yes/no questions, semantics, syntax

1. Introduction

The ability to comprehend questions is a crucial aspect of language processing. Imagine the consequence of being unable to comprehend questions such as, “Are you hungry?”, “Is the temperature too hot for you?”, or “Do you understand the instructions of this task?”. The first two examples represent questions that can lead to dire health consequences if answered incorrectly. The final example represents questions that can lead to dire consequences in a research study. In the current study, we investigated the relationship between yes/no question comprehension (i.e., questions that can be answered, “yes” or “no”) and dysfunction in cortical brain regions in the left hemisphere of patients with acute stroke.

Questions were categorized as either Nonreversible (1a, below) or Reversible (2a). Nonreversible questions inquired about a semantic property of the subject noun (e.g., sourness, color), while Reversible questions inquired about the relationship between the subject and object nouns along a particular semantic dimension (e.g., size, time). Reversible questions are so called because it is possible to form grammatical and plausible sentences even when the subject and object nouns reverse their positions (e.g., “Is a horse larger than a dog?” vs. “Is a dog larger than a horse?”). In contrast, with Nonreversible questions, there is no chance to reverse positions since the subject is the only noun. In general for yes/no questions, the copula (represented by “are” and “is”, in the examples below) is believed to move from its position just before the verb in the declarative form (1b & 2b) to the beginning of the sentence in the question.

1a) Are limes sour?

1b) Limes are sour.

2a) Is a horse lager than a dog?

2b) A horse is larger than a dog.

Our choice of stimuli allowed us to explore the relationship between cortical dysfunction and semantic and syntactic processing under conditions that differ from those in most studies of sentence comprehension, which mostly focus on declarative sentences (e.g., “The horse kicked the dog”, “The dog was kicked by the horse”). Studies employing declaratives usually involve picture-sentence matching (selecting one of two pictures that match a sentence) or picture verification (responding “True” or “False”, as to whether the sentence matches a picture of a scene). In contrast, our stimuli ask about entities that are not within view of the listener, forcing them to rely on their internal representations instead of continuous information from visual input. Furthermore, our task seems more natural since questions are more likely to occur than picture matching or verification, when outside of the lab. This difference in task demands might result in more natural processing.

Another important difference is that while most sentences in studies with declaratives include a verb, most often an action verb, our stimuli do not. In addition to providing semantic information about action, verbs provide syntactic information through argument structure and morphology that helps to identify the thematic roles (Agent, Patient, Theme, etc.), of the nouns. For example, in active sentences (“The horse kicked the dog”), the subject (horse) is also the agent, while the object (dog) is also the patient. As the majority of sentences are active, listeners can often use word order to determine the thematic roles of the nouns. However for passive sentences (“The dog was kicked by the horse”), word order is not a reliable cue as the subject is the patient while the object is the agent. Although passive sentences tend to be more difficult to comprehend, listeners can use the form of the verb (was kicked by) to determine who did what to whom.

In contrast to declaratives with verbs, for the questions in this study, listeners must rely on semantic knowledge about the relationship between the adjective and the nouns, along with word order to determine the correct answer. Nonreversible questions can be answered correctly by focusing on the semantic representation of the words. For example, in (1a) sourness is a semantic property of limes. Therefore, if the semantic representation of “lime” and “sour” are intact, then patients should, in most instances, be able to answer accurately.

The Reversible questions require knowledge of syntax (in addition to semantic knowledge) to determine the relationship between the nouns in question. For example, in (2a) the semantic property of “largeness” is not intrinsic to a horse or a dog in the way that “sourness” is intrinsic to limes. That is, a horse is larger than many objects (dog, pencil, hat), and smaller than many others (house, airplane, elephant). Therefore, syntax is required to understand that because “horse” comes before “larger”, the question pertains to whether the “horse” has the property of being larger than the “dog” and not the opposite.

In addition to the Question task, we also investigated performance on lexical tasks (i.e., Picture-Word Verification and Picture Naming). Similar to the Question task, we were interested in the relationship between cortical dysfunction and lexical performance. Furthermore, we were interested in behavioral performance across tasks. Including lexical tasks allowed us to determine whether regions participate in multiple tasks and, more generally, the degree to which problems with question comprehension were related to broader processing deficits that also affect lexical comprehension.

Finally, to provide better insight into the structure/function relationship in the brain, we chose patients whose stroke was acute in that imaging and language testing took place within roughly the day of stroke presentation. In such cases, language recovery due to either reorganization of the brain or strategies learned through rehabilitation is minimized in comparison to patients with chronic stroke. Furthermore, patients received both diffusion and perfusion weighted imaging to account for the entire dysfunctional brain. Diffusion weighted imaging reveals areas of ischemia, which approximates infarct or tissue death. Perfusion weighted imaging reveals regions of hypoperfusion, or low blood flow, which causes impaired function of the tissue even before, or without, cell death.

In the following, we provide a brief overview of studies that investigated the relationship between cortical dysfunction and sentence processing. All of these studies manipulated syntactic factors and most employed declaratives. We used this literature as a guidepost for the design and expectations in our own study.

It has long been believed that Broca's area is involved in processing syntactically complex sentences (Caramazza and Zurif, 1976). The exact role of Broca's area is highly debated with theories that include a role of BA 44 and/or 45 in working memory (Caplan, Alpert, Waters and Olvieri, 2000; Rogalsky, Matchin & Hickok, 2008), thematic role assignment (Caplan, Chen and Waters, 2008; Caplan, Stanczak, et al., 2008), or specific syntactic processes such as the Trace Deletion Hypothesis (Grodzinsky, 2000) (cf. Rogalsky and Hickock, 2011, for review). We found some evidence for dependence on Broca's area for processing reversible, but not non-reversible, sentences in a case study of an acute stroke patient with transient hypoperfusion to Broca's area (BA 44, 45) (Davis et al., 2008). The patient participated, before and after reperfusion, in a battery of tests that included: Nonreversible and Reversible yes/no questions, Video-Sentence Matching that included reversible declarative sentences (e.g., “The boy kicked the girl” vs. The girl was kicked by the boy”), and lexical tasks (reading, spelling, and naming). Before reperfusion, the patient had difficulty answering Reversible questions and declarative Reversible sentences but had relatively normal performance with Nonreversible questions. Additionally, he had difficulty with spelling and naming. After reperfusion, performance on all of these tasks was at ceiling. As the authors indicate, these data suggest that processing in these tasks relied to some extent on Broca's area, at least for this patient.

However, accumulating evidence indicates that regions beyond Broca's area (most notably the temporal-parietal-occipital region, which encompasses BA 22, 39, and 40, are also involved in sentence processing (Caplan, et al., 2004; Friederici, Ruschemeyer, Hane, & Fiebach, 2003; Vigneau et al., 2006). Most notably, these posterior regions seem to be involved in working memory. In fact, some studies report the involvement of these areas, but not Broca's area, in sentence comprehension (Dronkers et al., 2004).

In a recent study of acute stroke (Newhart et al., 2011), we did not find a strong relationship between ischemia in BA 44 or BA 45 and in a pattern of “asyntactic comprehension” (i.e., chance performance on passive reversible structures, more impaired performance for object-cleft than subject-cleft sentences, and more impaired performance for reversible than nonreversible sentences). However, we did find that ischemia in angular gyrus was associated with both asyntactic comprehension and impaired working memory in acute stroke. Also, in a continuous analysis, patients with ischemia in left BA 45 were more impaired in comprehending certain syntactically complex sentences (e.g. passive reversible sentences) than patients without ischemia in BA 45; they also had shorter backward digit spans than those without ischemia in BA 45. In contrast, patients with ischemia in left BA 44 had shorter forward digit spans only.

Dronkers et al. (2004) did not find an association between sentence comprehension and Broca's area. Instead, they found that performance was associated with dysfunction in: left frontal cortex (BA 46, 47), anterior superior temporal gyrus, superior temporal sulcus, and the angular gyrus. Deficits in comprehension of simple sentences were associated with lesions in BA 21, a region that was also associated with deficits on lexical tasks. Furthermore, among other regions, they found that deficits on syntactically complex sentences were associated with dysfunction of the angular gyrus, an area that they argued was involved in of working memory. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to evaluate whether BA 44 or 45 or other regions (e.g., areas implicated in working memory, such as BA 39 or 40) were critical for understanding reversible and nonreversible questions. We included frontal (BA 6, 44, 45, 46), temporal (BA 21, 22, 37) and parietal (BA 39, 40) regions in our investigation. In summary, we believe that question comprehension, as studied here, can provide greater insight into the relationship between various cortical regions of the left-hemisphere and language processing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

We studied a series of 38 patients (17 women), within 24 hours of hospital admission for symptoms of acute left hemisphere stroke, who were able to provide informed consent or indicate a family member to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: left-handedness (as reported by the patient or a close relative), history of previous neurological disease, history of uncorrected visual or hearing loss, or lack of premorbid proficiency in English, per the patient or family, reduced level of consciousness or sedation, or failure to obtain DWI or PWI imaging. All patients or their family members provided informed consent for the study, using methods and consent forms approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board. The mean age of the participants was 57 years (Range = 19-86; SD = 16) and the mean years of education was 13 (Range = 7-21; SD = 3.5).

2.2. Design

We presented patients with a battery of language tests for lexical and sentence processing. Here we focus on: Questions (yes/no), Oral Naming, and Name Comprehension. For each task the dependent variable was percent error.

2.2.1. Yes/No Questions

Patients were presented with 10 yes/no questions (i.e., questions that can be answered either “yes” or “no”; see Appendix). Six of these questions were Nonreversible (e.g., Are limes sour?), while four of these questions were Reversible (e.g., Is a horse larger than a dog?). For each question type, the correct answer for half of the questions was “yes”. In order to be counted as correct, patients had to answer “yes” or “no”. They could not answer for example, “A horse is larger”, for although this answer does display understanding of the semantic relation, it reflects difficulty understanding the question as posed.

2.2.2. Picture-Word Verification

Participants were presented with a picture (e.g., comb) that corresponded either to a correct visual depiction of the word (comb), a semantically related foil (brush), or a phonologically related foil (coat). Participants were asked to judge whether or not the word and picture matched. The series of 17 items were presented three times (such that each item appeared once in a series of 17 trials); each time a given item was presented with a different foil or target (in random order across stimuli).

2.2.3. Picture Naming

We asked participants to orally name 17 pictures of common objects (e.g., chair). Synonyms were scored as correct (seat for chair); however, responses were scored as incorrect if they were superordinate (furniture for chair) or subordinate (recliner for chair) to the item.

2.3. Imaging

Magnetic Resonance Imaging included Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) with or without T1 and T2 (to rule out old infarcts), Susceptibility Weighted Images (to rule out hemorrhage), diffusion-weighted images (DWI), Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) maps, and dynamic-susceptibility contrast echo-planar Perfusion Weighted Images (PWI) obtained parallel to the AC-PC line on Siemens 1.5 Tesla clinical scanner or Philips 3 Tesla research scanner. Slice thickness was 5 mm for most sequences acquired; however, some patients had 1 mm isotropic MPRAGE sequence instead of a T1-weighted sequence. PWI was obtained with power-injection of a weight based dose of Gadolinium at 5 cc/sec. Five mm thick slices, usually 17-20 slices to achieve whole brain coverage, were obtained typically with a TR of 1570 msec and a TE of 30 msec. DWI typically had a TR of 5100 and a TE of 90 msec. ADC maps were generated from B0 and B1000 diffusion scans. Scans were analyzed to evaluate for ischemia (infarct and/or hypoperfusion) in nine Brodmann areas (6, 21, 22, 37, 39, 40, 44, 45, 46), on a standard atlas, (Damasio & Damasio, 1989) by two technicians masked to the language scores (100% agreement). Dysfunctional tissue was defined as bright on DWI and dark on ADC and/or hypoperfused on PWI (mean of >4 sec delay in time to peak arrival of Gadolinium to the region of interest compared to the homologous region in the right hemisphere). This degree of hypoperfusion corresponds to dysfunctional tissue defined by PET (Zaro-Weber, et al. 2010; Sobesky, et al. 2004) and correlates well with severity of deficits associated with tissue dysfunction (Hillis et al., 2001). For each patient, the volume of infarct and volume of hypoperfusion were determined by tracing and measuring the dysfunctional tissue on each slice using the ImageJ software http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/download.html, multiplying the area by slice thickness, and adding the volume of each slice.

There are presently many ways of selecting regions of interest, including using anatomical landmarks such as specific gyri, approximate locations Brodmann's areas on a published atlas (based on locations of where majority of a small number of people at autopsy were found to have a particular cytoarchitecture), defining ROIs using coordinates of a single brain e.g. Talairach space or average population based MNI Space (Mazziotta et al., 2001, Mori et al., 2008), specifying anatomical parcels (Mori et al., 2008), or even individual voxels on a given atlas to which the patient's scans are registered (Bates, et al., 2003). However, all of these methods have strengths and weaknesses and all are limited by the individual variability in sizes and shapes of brains and variability of the sulci and gyri (Fischl et al., 2008; Eickhoff et al., 2005, Amunts et al., 2007, Eickhoff et al., 2007; Leonard et al., 1998). We chose to use Brodmann areas as our regions of interest, using a published atlas to define the approximate locations (Damasio and Damasio, 1989), because (1) we have established high inter-rater reliability (>95% point-to point percent agreement) in scoring presence/absence of dysfunction in these BAs using this atlas; (2) autopsy studies show that there is remarkable reliability in the approximate locations of the cytoarchitectural fields, but not the precise architectural fields based on landmarks at autopsy; Amunts et al., 2007); and (3) cytoarchitecture likely corresponds to some degree to function (in terms of some role in a functional network). However, we recognize that we have no way of knowing that an individual had a particular cytoarchitecture (or only that particular cytoarchitecture) in a given BA that we identified using anatomical landmarks.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

To evaluate the effect of ischemia on error scores, we conducted Mann-Whitney tests (two-tailed) to compare patients with ischemia vs. patients without ischemia in each Brodmann area. We applied a Bonferroni correction for 9 comparisons (9 Brodmann areas), so that an alpha level of .006 or less was considered above chance. Furthermore, we also conducted regression analyses to determine whether volume of dysfunctional tissue (infarct, hypoperfusion), predicted performance across tasks.

In addition, for regions with a significant association between error scores and ischemia, we wanted to determine whether the factors Age and Education and could also account for that outcome. Therefore, we conducted Mann-Whitney tests to investigate whether there was also an association between Age or Education and ischemia. A Bonferroni correction to control for multiple comparisons (9 Brodmann Regions) resulted in an alpha level of .006.

Finally, in addition to the analyses that test for the relationship between performance and dysfunction, we performed analyses to compare behavioral performance across tasks. The goal was to gain a more precise understanding of the relationship between error rate on the lexical and question tasks. As presented in Table 1, correlation analyses indicated that there was a significant positive correlation between all tasks (p <.01). On closer inspection of the data, we found that patients fell into one of three groups based on performance of Nonreversible and Reversible questions: No-Error (no errors; N=14), Reversible-Only (errors on Reversible questions only; N=14), and Nonreversible-Reversible (errors on both Nonreversible and Reversible questions; N=10). We then conducted Mann-Whitney tests (two-tailed) to investigate whether there were significant differences between these groups on performance in the lexical tasks. A Bonferroni correction to control for multiple comparisons between groups resulted in an alpha level of 0.02. If groups that are worse at question tasks are also significantly worse at the lexical tasks, it would provide further evidence that question comprehension is intertwined to some degree with processing required for lexical tasks.

Table 1. Correlation Matrix of Behavioral Tasks.

| Picture Naming | Picture-Word Verification | Nonreversible Questions | Reversible Questions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Picture Naming | 1 | .58* | .45* | .56* |

| Picture-Word Verification | .58* | 1 | .64* | .65* |

| Nonreversible Questions | .45* | .64* | 1 | .47* |

| Reversible Questions | .56* | .65* | .47* | 1 |

Note. After correcting for multiple comparisons, results were considered significant if p < 0.01

Before continuing to the results it is worth noting that because the Mann-Whitney test is non-parametric and analyzes ordinal data, it is more appropriate to discuss the results as they relate to median and the range of values rather than the mean and standard deviation (Olsen, 2003). Therefore, we report the median and range of the percentage of errors for patients with and without ischemia, respectively.

3. Results

Table 2 presents, for each task, descriptive statistics that detail the distribution of scores for patients with and without ischemia in each Brodmann Area and also whether the performance of these groups was significantly different. Overall, patients had a median of 0% (Range = 0-83.3) errors on Nonreversible questions, and 25% (Range = 0-100) errors on Reversible questions. Interestingly, 48% and 74% of errors occurred when the answer was “no” for the Nonreversible and Reversible questions respectively. Finally, patients had a median of 12% (Range = 0-100) errors for Picture Naming and 26% (Range = 0-100) errors for Picture-Word Verification.

Table 2. For each Task, Decriptive Statistics and p-value for each Broadmann Area (BA).

| Dysfunctional | Intact | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Task & BA | N | Range | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | N | Range | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | P-Value |

| Nonreversible Comprehesion | |||||||||||

| BA 6 | 11 | 0-83 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 27 | 0-50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.22 |

| BA 44 | 9 | 0-83 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 29 | 0-50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 |

| BA 45 | 5 | 0-33 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 33 | 0-83 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.73 |

| BA 46 | 6 | 0-33 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 32 | 0-83 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0.8 |

| BA 21 | 10 | 0-83 | 0 | 25 | 33 | 28 | 0-50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 |

| BA 22 | 17 | 0-83 | 0 | 25 | 33 | 21 | 0-50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.06 |

| BA 37 | 15 | 0-83 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 23 | 0-50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.08 |

| BA 39 | 14 | 0-83 | 0 | 17 | 33 | 24 | 0-50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 |

| BA 40 | 16 | 0-83 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 22 | 0-50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.09 |

| Reversible Comprehesion | |||||||||||

| BA 6 | — | 0-100 | 38 | 50 | 63 | — | 0-75 | 0 | 25 | 38 | 0.006* |

| BA 44 | — | 0-100 | 25 | 50 | 50 | — | 0-75 | 0 | 25 | 50 | 0.04 |

| BA 45 | — | 0-100 | 25 | 50 | 50 | — | 0-100 | 0 | 25 | 50 | 0.33 |

| BA 46 | — | 0-100 | 25 | 38 | 69 | — | 0-75 | 0 | 25 | 50 | 0.22 |

| BA 21 | — | 0-100 | 31 | 50 | 50 | — | 0-75 | 0 | 25 | 50 | 0.02 |

| BA 22 | — | 0-100 | 25 | 50 | 50 | — | 0-75 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 0.009 |

| BA 37 | — | 0-100 | 25 | 50 | 50 | — | 0-75 | 0 | 25 | 38 | 0.09 |

| BA 39 | — | 0-100 | 31 | 50 | 50 | — | 0-75 | 0 | 24 | 25 | 0.005* |

| BA 40 | — | 0-100 | 25 | 50 | 56 | — | 0-50 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 0.001* |

| Picture-Word Verification | |||||||||||

| BA 6 | — | 0-100 | 24 | 41 | 53 | — | 0-100 | 0 | 6 | 30 | 0.05 |

| BA 44 | — | 0-100 | 35 | 41 | 59 | — | 0-100 | 0 | 6 | 35 | 0.02 |

| BA 45 | — | 0-100 | 12 | 41 | 41 | — | 0-100 | 0 | 6 | 41 | 0.36 |

| BA 46 | — | 0-100 | 19 | 44 | 85 | — | 0-100 | 0 | 6 | 41 | 0.09 |

| BA 21 | — | 0-100 | 37 | 44 | 85 | — | 0-100 | 0 | 6 | 18 | 0.003* |

| BA 22 | — | 0-100 | 12 | 41 | 59 | — | 0-71 | 0 | 6 | 12 | 0.008 |

| BA 37 | — | 0-100 | 9 | 41 | 53 | — | 0-100 | 0 | 6 | 27 | 0.01 |

| BA 39 | — | 0-100 | 35 | 44 | 88 | — | 0-47 | 0 | 6 | 14 | < 0.001* |

| BA 40 | — | 0-100 | 29 | 44 | 77 | — | 0-41 | 0 | 6 | 12 | < 0.001* |

| Picture Naming | |||||||||||

| BA 6 | — | 0-100 | 65 | 86 | 94 | — | 0-100 | 0 | 24 | 74 | 0.11 |

| BA 44 | — | 0-100 | 76 | 86 | 94 | — | 0-100 | 0 | 24 | 83 | 0.2 |

| BA 45 | — | 0-100 | 76 | 86 | 100 | — | 0-100 | 0 | 24 | 88 | 0.23 |

| BA 46 | — | 0-100 | 87 | 91 | 99 | — | 0-100 | 0 | 24 | 83 | 0.1 |

| BA 21 | — | 0-100 | 84 | 95 | 100 | — | 0-100 | 0 | 24 | 68 | 0.03 |

| BA 22 | — | 0-100 | 76 | 94 | 100 | — | 0-100 | 0 | 12 | 24 | 0.001* |

| BA 37 | — | 0-100 | 47 | 88 | 100 | — | 0-100 | 0 | 12 | 42 | 0.004* |

| BA 39 | — | 0-100 | 39 | 92 | 100 | — | 0-100 | 0 | 14 | 56 | 0.007 |

| BA 40 | — | 0-100 | 46 | 91 | 100 | — | 0-100 | 0 | 12 | 30 | 0.003* |

Note. N = number of patients, Range = minimum and maximum score. Q1 = first quartile, Q2 = median, Q3 = third quartile. The N for each region was the same across all tasks. Scores represent error percentage. After correcting for multiple comparisons, results were considred significant (indicated by asterisk), if p <= 0.006.

3.1. Nonreversible Questions

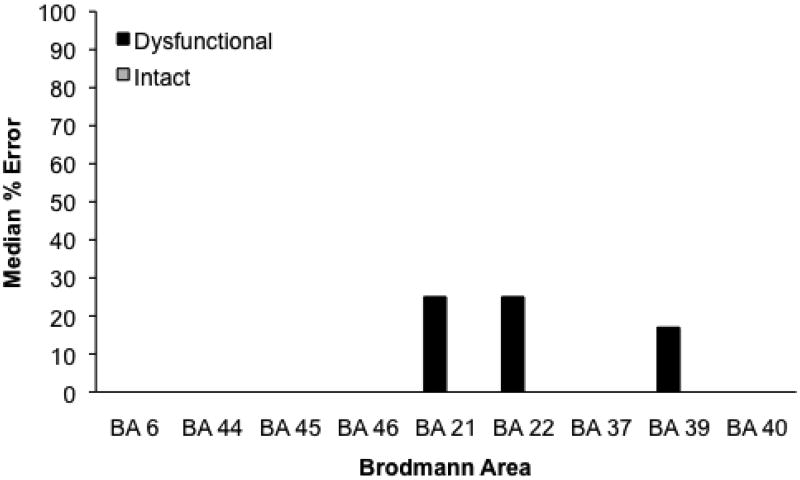

Figure 1 presents the median percent of errors for each Brodmann area. There was no association between performance and particular regions with ischemia. However, for both infarct and hypoperfusion, an increase in volume significantly predicted an increase in errors (error rate = 1.36 + InfarctVolume × 0.5; r2 = .33, p < .001; error rate = 2.92 + HypoperfusionVolume × 0.4, r2 = 0.5, p < .001). Finally, there was no association between error rate and Age or Education.

Figure 1.

Median percentage of errors on Nonreversible questions for patients with and without ischemia in each Brodmann area. A significant difference by the Mann-Whitney test is marked by an asterisk.

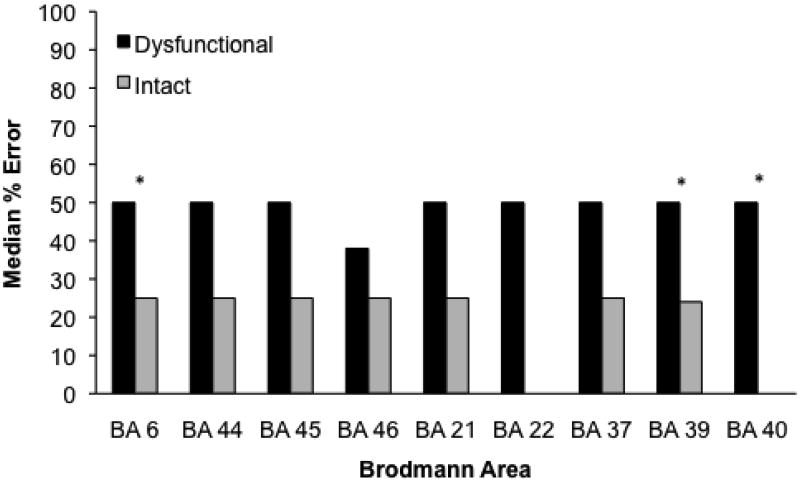

3.2. Reversible Questions

Figure 2 presents the median percent of errors for each Brodmann area. Errors were associated with ischemia in BA 6 (Mdn = 50, Range = 0-100 vs. 25, 0-75; Mann Whitney, Z = 2.75, p = .006), BA 39 (Mdn = 50, Range = 0-100 vs. 12.5, 0-75; Mann-Whitney, Z = 2.8, p = .005), and BA 40 (Mdn = 50, Range = 0-100 vs. 0, 0-50; Mann-Whitney, Z = 3.21, p = .001), for patients with and without ischemia in each BA, respectively. For both infarct and hypoperfusion, an increase in volume significantly predicted an increase in errors (error rate = 21 + InfarctVolume × 0.4, r2= .12, p = .02; error rate = 24 + HypoperfusionVolume × 0.3, r2 = .11, p = .03) There was no association between error rate and Age or Education.

Figure 2.

Median percentage of errors on Reversible questions for patients with and without ischemia in each Brodmann area. A significant difference by the Mann-Whitney test is marked by an asterisk.

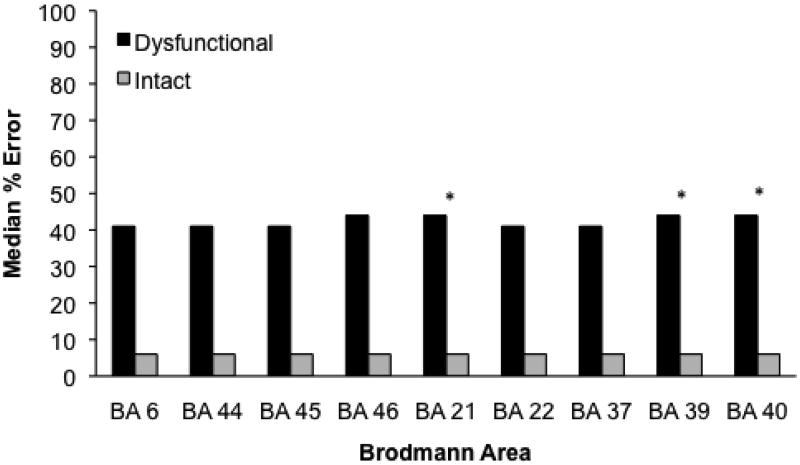

3.3. Picture-Word Verification

Figure 3 presents the median percent of errors for each Brodmann area. Errors were associated with ischemia in BA 21 (Mdn = 44, Range = 0-100 vs. 6, 0-100; Mann-Whitney, Z = 2.95, p = .003), BA 39 (Mdn = 44, Range = 0-100 vs. 6, 0-47; Mann-Whitney, Z = 3.46, p < .001), and BA40 (Mdn = 44, Range = 0-100 vs. 6, 0-41; Mann-Whitney, Z = 3.34, p < .001). In addition, only Volume of infarct predicted error (error = 11.27 + InfarctVolume × 0.8, r2 = .38, p < .001. There was no association between error rate and Age, or Education.

Figure 3.

Median percentage of errors on Picture-Word Verification for patients with and without ischemia in each Brodmann area. A significant difference by the Mann-Whitney test is marked by an asterisk.

Table 3 presents descriptive statistics that detail the distribution of error scores and volume of tissue dysfunction (infarct, hypoperfusion) for each group (No-Error, Reversible-Only, NonReversible-Reversible), and also whether performance or volume of dysfunction between these groups is significantly different. The Nonreversible-Reversible, Reversible-Only, and No-Error groups committed median error scores of: 65% (Range = 6-100), 18% (Range = 0-47), and 0% (Range = 0-12) errors, respectively. The Nonreversible-Reversible group committed significantly more errors than both the Reversible-Only group (Mann-Whitney, Z = 2.72, p = .007) and the No-Error group (Mann-Whitney, Z = 3.92 p < .001). Furthermore, the Reversible-Only group committed significantly more errors than the No-Error group (Mann-Whitney, Z = 2.94, p = .003).

Table 3. For each Task and Volume of Tissue Dysfunciton, Decriptive Statistics and p-value for each group.

| Task/Volume of Tissue Dysfunction | N | Range | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | No-Error | Reversible-Only | NonReversible-Reversible |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NonReversible Comprehension | ||||||||

| No-Error | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | 1 | < 0.001* |

| Reversible-Only | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | < 0.001* |

| NonReversible-Reversible | 10 | 17-83 | 33 | 33 | 46 | — | — | — |

| Reversible Comprehension | ||||||||

| No-Error | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | < 0.001* | < 0.001* |

| Reversible-Only | — | 25-75 | 25 | 25 | 50 | — | — | 0.07 |

| NonReversible-Reversible | — | 25-100 | 50 | 50 | 50 | — | — | — |

| Picture-Word Verification | ||||||||

| No-Error | — | 0-12 | 0 | 0 | 5 | — | 0.003* | <.001* |

| Reversible-Only | — | 0-47 | 8 | 18 | 41 | — | — | 0.007* |

| NonReversible-Reversible | — | 6-100 | 41 | 65 | 99 | — | — | — |

| Picture Naming | ||||||||

| No-Error | — | 0-100 | 0 | 6 | 14 | — | 0.03 | <0.00l* |

| Reversible-Only | — | 0-100 | 10 | 41 | 99 | — | — | 0.19 |

| NonReversible-Reversible | — | 24-100 | 78 | 87 | 99 | — | — | — |

| Infarct Volume | ||||||||

| No-Error | — | 0-60 | 0.3 | 3 | 7 | — | 0.04 | 0.002* |

| Reversible-Only | — | 0-27 | 4 | 14 | 17 | — | — | 0.001* |

| NonReversible-Reversible | — | 0.75-129 | 29 | 38 | 44 | — | — | — |

| Hypoperfusion Volume | ||||||||

| No-Error | — | 0-13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | 0.02 | 0.008* |

| Reversible-Only | — | 0-53 | 0 | 2 | 29 | — | — | 0.13 |

| NonReversible-Reversible | — | 0-122 | 4 | 36 | 68 | — | — | — |

Note. No-Error = no error on NonReversible or Reversible questions, Reversibe-Only = Errors only on Reversible questions, NonReversible-Reversible = Errors on both Nonreversible and Reversible questions. The number of subjects in each group was constant across tasks. Volume of lesion was measure in cubic centimeters. After correcting for multiple comparisons, results were considred significant (indicated by asterisk), if p <= 0.02.

In regards to volume of dysfunction, as measured in cubic centimeters, the NonReversible-Reversible group had a greater volume of infarct than both the No-Error group (Mdn = 38, Range = .75-129 vs. 14, 0-27; Mann-Whitney, Z = 3.13, p = .002), and the Reversible-Only group (Mdn = 38, Range = 75-129 vs. 3, 0-60; Mann-Whitney, Z = 3.25, p = .001). Additionally, the NonReversible-Reversible group had a greater amount of hypoperfusion than the No-Error group (Mdn = 36, Range = 0-122 vs.006, 0-13; Mann-Whitney, Z = 2.66, p = .008).

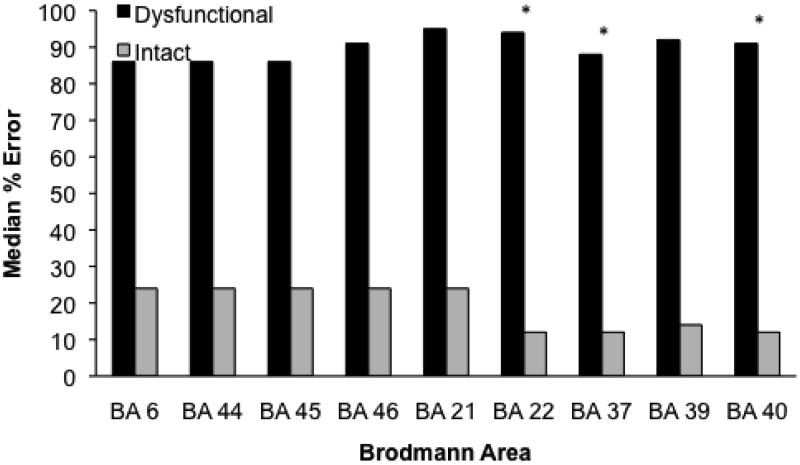

3.4. Picture Naming

Figure 5 presents the median percent of errors for each Brodmann area. Errors were associated with ischemia in BA 22 (Mdn = 95, Range = 0-100 vs. 12, 0-100; Mann-Whitney, Z = 13.26, p < .001), BA 37 (Mdn = 88, Range = 0-100 vs. 12, 0-100; Mann-Whitney, Z = 2.91, p = .004), and BA 40 (Mdn = 91, Range = 0-100 vs. 12, 0-100; Mann-Whitney, Z = 3, p = .003). In addition, only volume of infarct predicted error rate (error rate = 30.71 + InfarctVolume × 0.8, r2 = .2, p < .003). There was no association between error rate and volume of hypoperfusion, Age, or Education.

The Nonreversible-Reversible, Reversible-Only, and No-Error groups committed median error scores of: 87% (Range = 24-100), 40.5% (Range = 0-100), and 6% (Range = 0-100), respectively. The Nonreversible-Reversible group committed significantly more errors than the No-Error Group (Mann-Whitney, Z = 3.48, p < .001). There were no other significant differences.

4. Discussion

We tested patients with acute stroke to investigate the relationship between yes/no question comprehension and left hemisphere cortical brain damage. In addition, we administered lexical tasks (i.e., Picture-Word Verification & Picture Naming) to determine whether the deficits were strictly related to sentence processing or whether they also encompassed lexical processing. We found that, for Nonreversible questions, errors were only associated with volume of infarct and hypoperfusion. For Reversible questions, errors were associated with tissue dysfunction in BA 6, 39, and 40, as well as volume of infarct and hypoperfusion. For the Picture-Word Verification task, errors were associated with dysfunction in BA 21, 39, and 40, as well as volume of infarct. Finally, for Picture-Naming, errors were associated with dysfunction in BA 22, 37, and 40, as well as volume of infarct. In the rest of this section, we discuss the role of these regions in relation to the question comprehension tasks.

For Nonreversible questions the results suggest that errors stem from tissue dysfunction that leads to deficits across multiple levels of language processing (i.e., lexical, simple sentence, and syntactic processing). This is highlighted by the results indicating that the NonReversible-Reversible group made significantly more errors than — the No-Error and Reversible-Only groups on Picture-Word Verification, the No-Error group on Naming, and the Reversible-Only group on Reversible questions. This pattern of performance is likely due to the fact that the NonReversible-Reversible patients had a greater volume of ischemia than other patients, as an increase in the volume of infarct was related to an increase in errors for each task. In this light, it makes sense that patients with the highest volumes of ischemia would generally have the worst performance, as there is a greater chance of dysfunction in regions associated with a particular task. Therefore, due to their relative ease of processing, Nonreversible questions seemed to show deterioration only with a high volume of ischemia that affected language processing more globally.

For Reversible questions, similar to the situation with Nonreversible questions, the results suggest errors stem from tissue dysfunction that leads to deficits in both lexical and syntactic processing. However, in this case performance is more closely associated with dysfunction in particular regions. Deficits in semantic processing are highlighted by the fact that the Reversible-Only group made significantly more errors than the No-Error group on Picture-Word Verification. Furthermore, two of the regions associated with Reversible questions were also associated with lexical tasks (BA 39 with Picture-Word Verification, BA 40 with both the verification and naming tasks). Syntactic processing deficits are also highlighted by the regions associated with task performance. In particular, BA 6 was only associated with Reversible question comprehension.

Evidence from the literature suggests that BA 39, and 40 are involved in mapping between phonology and semantics (DeLeon et al. 2007; Graves, Grabowski, Mehta, & Gupta, 2008; Hickok & Poeppel, 2004; Okada & Hickok, 2006; Vigneau et al., 2006). BA 39 receives input from multiple modalities (auditory, visual, tactile, etc.), and is noted as a region involved in semantic processing, at least in tasks that involve lexical decision (Binder, Desai, Graves, & Conant, 2009; Mummery, Patterson, Hodges, & Price, 1998). In our previous study of syntactic processing (Newhart et al., 2011), we found that BA 39 was associated with complex sentence processing as well as working memory tasks (i.e., forward and backward digit span). Overall, this suggests that this region became more crucial as the semantic, syntactic and phonological complexity increased with the Reversible sentences, which in effect increased demands on working memory.

In contrast, BA 40 may be more involved in phonological processing. BA 40 is often associated with phonological working memory, often as a site for phonological storage (Jonides et al., 1998; Moser, Baker, Sanchez, Rorden, & Fridriksson, 2009; Romero, Walsh, & Papagno, 2006 Stoeckel, Gough, Watkins, & Devlin, 2009; Vigneau et al., 2006). As in the case of BA 39, as working memory demands increase for the Reversible questions, so too does the importance of processing in BA 40.

Finally, BA 6 was the only region associated with Reversible question comprehension and, in addition, was not associated with any other task. These results are similar to our recent findings with passive and active reversible sentences in patients with acute stroke (Newhart et al., 2011). In that study, we also found an association between asyntactic comprehension and BA 6 but not with either BA 44 or BA 45. However, these results contrast with Davis et al. 2008, which found impairment on yes/no questions when BA 44 and BA 45 were hypoperfused and improvement when these regions were reperfused. One potential reason for this discrepancy is that for the current study, there were very few patients with dysfunction in these regions (BA 44 = 9, BA 45 = 6), which raises the possibility that we did not have sufficient power to detect a significant relationship between ischemia in these regions and comprehension of Reversible questions. It is possible then, that we would find a relationship between performance and dysfunction in these regions with a larger pool of patients.

BA 6 is often associated with articulatory planning and therefore is thought to be involved in the phonological rehearsal (Swartz, et al., 1996; D'Esposito et al., 1999; D'Esposito & Postle, 1999; Hickok & Poeppel, 2004). Indeed, in our previous study we found that BA 6 was associated with forward and backward digit span, which test short-term and working memory respectively. Therefore, although these results do not completely rule out the possibility that BA 6 is directly involved with syntactic processing, we believe that these results converge to suggest that BA 6 influenced comprehension of the Reversible sentences through phonological rehearsal. As sentence complexity increases, rehearsal helps to remember the words and word order - two aspects that are necessary to build and maintain syntactic structure. Further research is required to reconcile the role of regions in the inferior frontal gyrus (i.e., Broca's area) and adjacent areas, such as BA 6, in syntactic processing during question comprehension.

A deterioration of working memory provides a plausible explanation as to why patients performed better on Reversible questions when the correct answer was “yes” then when it was “no”. For these items, the subject-noun was, for lack of a better term, the agent when the correct answer was “yes”, and the patient when the correct answer was “no”. If there is a bias to consider the first noun as the agent, as is often observed with declarative sentences, then “no” questions would be more likely to require reanalysis. Additional analysis increases reliance on working memory, an aspect of processing that seems to be lacking in these patients. In effect, these results are similar to studies of active (e.g., The horse kicked the dog) versus passive sentences (e.g., The horse was kicked by the dog). Patients are generally better at comprehending active sentences in which the subject-noun is the agent than passive sentences in which the subject-noun is the patient. As we argue with the Reversible “no” questions, errors in passives are often attributed to listeners assigning the subject-noun to the role of agent.

5. Conclusion

Our goal was to investigate cortical regions associated with the comprehension of Nonreversible and Reversible questions. Our motivation to use questions came from an interest in observing the relation between cortical regions and performance when the sentence structure is different from declaratives and when the task demands are different (due to the nature of asking a questions and the fact that our items do not contain verbs). The pattern of results indicates that multiple interacting regions participate in both lexical and sentence processing. However, these regions seem to vary in the extent that they processes semantics, phonology, and syntax. Therefore, as task demands change so too does the necessity of involvement across regions.

Performance on the lexical tasks was associated with posterior-temporal and inferior-parietal regions, which, in turn, are associated with semantic and phonological processing. Nonreversible question comprehension seemed to be relatively insulated from errors, as deterioration in performance required more tissue dysfunction than Reversible questions that affected multiple levels of processing. In contrast, Reversible questions are more complex in that they require knowledge of syntax in addition to semantic knowledge. This additional complexity puts more pressure on working memory, which is involved in integrating semantic and phonological representations. This is reflected by the fact that two posterior areas (BA 39, 40), as well as BA 6 (an anterior region that is often considered crucial for phonological working memory), were associated with Reversible but not Nonreversible questions. BA 39 is a multimodal area that plays a role in linking between semantics and phonology, while BA 6, and BA 40 are associated with aspects of phonology (storage, and rehearsal). Ultimately, each of these regions are involved in aspects of processing that become more important as syntactic processing difficulty increases. In sum, the pattern of errors is associated with the effect of task demands over interacting cortical regions. As processing demands in a task increase across aspects of language, areas associated with those aspects become critical to performance.

Overall, the results are similar to what has been found in the literature with declaratives. This is comforting, as it seems unlikely that question comprehension would require radically different processing than declaratives. However, as this is one of a limited number of question comprehension studies, it will take further research to determine whether there are any crucial differences. Either way, a greater understanding of sentence comprehension, will provide a clearer picture as to sentence processing in general.

Figure 4.

Median percentage of errors on Picture-Naming for patients with and without ischemia in each Brodmann area. A significant difference by the Mann-Whitney test is marked by an asterisk.

We examined the relationship between ischemia and performance on yes/no questions.

Nonreversibles (Are limes sour?) are associated with volume of tissue dysfunction.

Reversibles (Is a horse larger than a dog?) are associated with BA 6, 39, 40.

Nonreversible errors related to more global processing deficits.

Reversible errors associated with semantic and working memory deficits.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH/NIDCD R01 DC05375 and R01 DC 03681. We gratefully acknowledge this support, and the participation of the patients.

Appendix. NonReversible and Reversible Questions

NonReversible Questions

Are limes sour? (yes)

Does a zebra have stripes? (yes)

Do most people have two eyes? (yes)

Are bananas red? (no)

Do dogs normally fly? (no)

Do cats bark? (no)

Reversible Questions

Is a horse larger than a dog? (yes)

Does May come before June? (yes)

Is a grapefruit larger than a watermelon? (no)

Does Friday come after Saturday? (no)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amunts K, Schleicher A, Zilles K. Cytoarchitecture of the cerebral cortex-More than localization. Neuroimage. 2007;37:1061–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates E, Wilson SM, Saygin AP, Dick F, Sereno MI, Knight RT, Dronkers NF. Voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping. Nature Neuroscience. 2003;6:448–450. doi: 10.1038/nn1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder JR, Desai RH, Graves WW, Conant LL. Where is the semantic system? A critical review and meta-analysis of 120 functional neuroimaging studies. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19:2767–2796. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caramazza A, Zurif EB. Dissociation of algorithmic and heuristic processes in language comprehension: Evidence from aphasia. Brain and Language. 1976;3:572–582. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(76)90048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D, Alpert N, Waters G, Olivieri A. Activation of Broca s area by syntactic processing under conditions of concurrent articulation. Human Brain Mapping. 2000;9:65–71. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(200002)9:2<65::AID-HBM1>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D, Chen E, Waters G. Task-dependent and task-independent neurovascular responses to syntactic processing. Cortex. 2008;44:257–275. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D, Stanczak L, Waters G. Syntactic and thematic constraint effects on blood oxygenation level dependent signal correlates of comprehension of relative clauses. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;20:643–656. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio H, Damasio A. Lesion analysis in neuropsychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Kleinman JT, Newhart M, Gingis L, Pawlak M, Hillis AE. Speech and language functions that require a functioning Broca's area. Brain and Language. 2008;105:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon J, Gottesman RF, Kleinman JT, Newhart M, Davis C, Heidler-Gary J, et al. Hillis AE. Neural regions essential for distinct cognitive processes underlying picture naming. Brain. 2007;130:1408–1422. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Esposito M, Postle BR. The dependence of span and delayed-response performance on prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychologia. 1999;37:1303–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(99)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Esposito M, Postle BR, Ballard D, Lease J. Maintenance versus manipulation of information held in working memory: an event related fMRI study. Brain and Cognition. 1999;41:66–86. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1999.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dronkers N, Wilkin D, Van Valin R, Redfern B, Jaeger J. Lesion analysis of the brain areas involved in language comprehension. Cognition. 2004;92:145–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Rajendran N, Busa E, Augustinack J, Hinds O, Yeo BT, Mohlberg H, Amunts K, Zilles K. Cortical folding patterns and predicting cytoarchitecture. Cerebral Cortex. 2008;18:1973–1980. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Paus T, Caspers S, Grosbras MH, Evans AC, Zilles K, Amunts K. Assignment of functional activations to probabilistic cytoarchitectonic areas revisited. Neuroimage. 2007;36:511–521. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Stephan KE, Mohlberg H, Grefkes C, Fink GR, Amunts K, Zilles K. A new SPM toolbox for combining probabilistic cytoarchitectonic maps and functional imaging data. Neuroimage. 2005;25:1325–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friederici AD, Ruschemeyer SA, Hahne A, Fiebach CJ. The role of left inferior frontal and superior temporal cortex in sentence comprehension: Localizing syntactic and semantic processes. Cerebral Cortex. 2003;13:170–177. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves WW, Grabowski TJ, Mehta S, Gupta P. The left posterior superior temporal gyrus participates specifically in accessing lexical phonology. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;20:1698–1710. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodzinsky Y. The neurology of syntax: Language use without Broca s area. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2000;23:1–21. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x00002399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickok G, Poeppel D. Dorsal and ventral streams: a framework for understanding aspects of the functional anatomy of language. Cognition. 2004;92:67–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis AE, Wityk RJ, Tuffiash E, Beauchamp NJ, Jacobs MA, Barker PB, Seines OA. Hypoperfusion of Wernicke's area predicts severity of semantic deficit in acute stroke. Annals of Neurology. 2001;50:561–566. doi: 10.1002/ana.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonides J, Schumacher EH, Smith EE, Koeppe RA, Awh E, Reuter-Lorenz PA, et al. Willis CR. The role of parietal cortex in verbal working memory. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:5026–5034. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-13-05026.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard CM, Puranik C, Kuldau JM, Lombardino LJ. Normal variation in the frequency and location of human auditory cortex landmarks. Heschl's gyrus: Where is it? Cerebral Cortex. 1998;8:397–406. doi: 10.1093/cercor/8.5.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazziotta J, Toga A, Evans A, Fox P, Lancaster J, Zilles K, et al. A probabilistic atlas and reference system for the human brain: International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM) Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences. 2001;356:1293–1322. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Oishi K, Jiang H, Jiang L, Li X, Akhter K, et al. Mazziotta J. Stereotaxic white matter atlas based on diffusion tensor imaging in an ICBM template. Neuroimage. 2008;40:570–582. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser D, Baker JM, Sanchez CE, Rorden C, Fridriksson J. Temporal Order Processing of Syllables in the Left Parietal Lobe. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:12568–12573. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5934-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mummery CJ, Patterson K, Hodges JR, Price CJ. Functional neuroanatomy of the semantic system: Divisible by what? Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1998;10:766–777. doi: 10.1162/089892998563059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhart M, Trupe LA, Gomez Y, Cloutman L, Molitoris JJ, Davis C, et al. Hillis AE. Asyntactic comprehension, working memory, and acute ischemia in Broca's area versus angular gyrus. Cortex. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.09.009. Published ahead of print on October 11, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen CH. Review of the use of statistics in Infection and Immunity. Infection and Immunity. 2003;71:6689–6692. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.12.6689-6692.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada K, Hickok G. Left posterior auditory-related cortices participate both in speech perception and speech production: Neural overlap revealed by fMRI. Brain and Language. 2006;98:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogalsky C, Hickok G. The role of Broca's area in sentence comprehension. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011;23:1664–80. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2010.21530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogalsky C, Matchin W, Hickok G. Broca s area, sentence comprehension, and working memory: An fMRI study. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2008;2:14. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.014.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero L, Walsh V, Papagno C. The neural correlates of phonological short-term memory: A repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2006;18:1147–1155. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.7.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobesky J, Zaro-Weber O, Lehnhardt FG, Hesselmann V, Thiel A, Dohmen C, et al. Heiss WD. Which time-to-peak threshold best identifies penumbral flow? A comparison of perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:2843–2847. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000147043.29399.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeckel C, Gough PM, Watkins KE, Devlin JT. Supramarginal gyrus involvement in visual word recognition. Cortex. 2009;45:1091–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz BE, Halgren E, Simpkins F, Mandelkern M. Studies of working memory using 18FDG-positron emission tomography in normal controls and subjects with epilepsy. Life Sciences. 1996;58(22):2057–2064. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigneau M, Beaucousin V, Herve PY, Duffau H, Crivello F, Houde O, et al. Tzourio-Mazoyer N. Meta-analyzing left hemisphere language areas: Phonology, semantics, and sentence processing. Neuroimage. 2006;30:1414–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaro-Weber O, Moeller-Hartmann W, Heiss WD, Sobesky J. Maps of time to maximum and time to peak for mismatch definition in clinical stroke studies validated with positron emission tomography. Stroke. 2010;41:2817–2821. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.594432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]