Abstract

Introduction. Mycetoma is a localized, chronic, progressive, granulomatous, inflammatory, non contagious, tumour-like lesion with sinuses discharging different types of granules. The organisms are usually inoculated into any body part subject to trauma-usually the foot. Treatment is medical and/or surgical. Prognosis is good in early cases with high recurrences in late cases or those inadequately treated. The authors describe the successful treatment of a severe case of leg mycetoma, with combined surgical and medical therapies.

1. Introduction

Mycetoma is also called maduromycosis, kirinagra, and Madura foot [1]. It is a clinical entity characterized by a chronic, localized, progressive, granulomatous, inflammatory, noncontagious, tumour-like lesion, common in the tropics and subtropics [2]. The highest incidence is in Sudan and it is 4 times more common in males, most often in farmers and field workers who are frequently exposed to minor penetrating wounds by thorns and splinters [3]. 75% of the lesions occur in the lower limbs [3]. It usually involves the foot especially in those who walk barefoot. The trauma results in the classic triad tumefaction, multiple sinuses discharging different types of granules. The grains are an aggregation of organisms, either fungi (Eumycetes) Schizomycetes (gram-positive filamentous bacteria, true bacteria {botryomycosis}), or in combination. Diagnosis entails clinical exam, high index of suspicion, and isolation of the organism [4].

2. Case Presentation

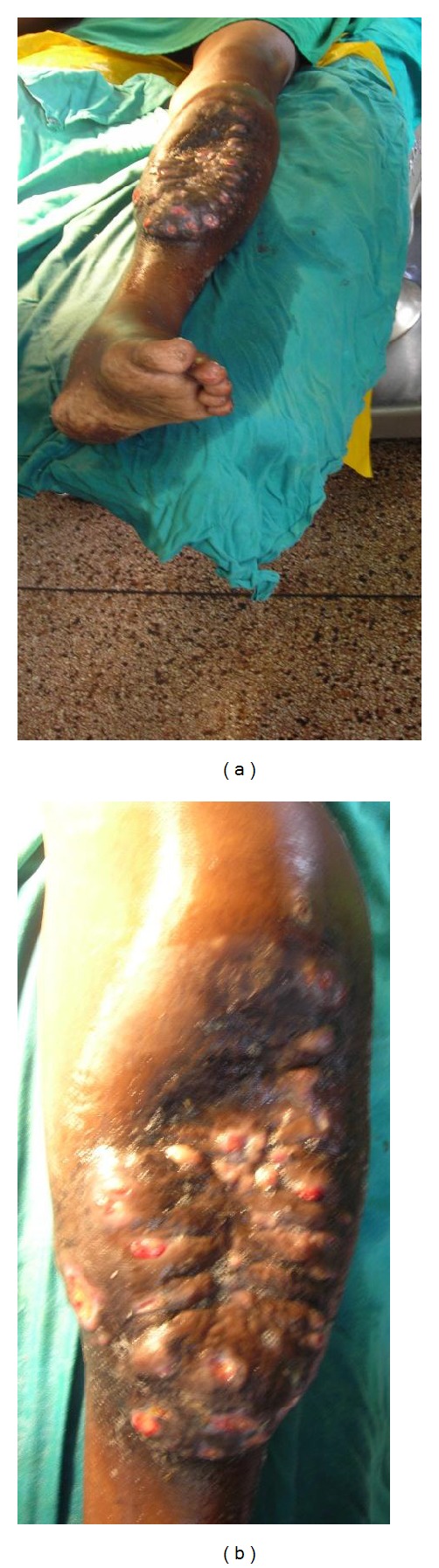

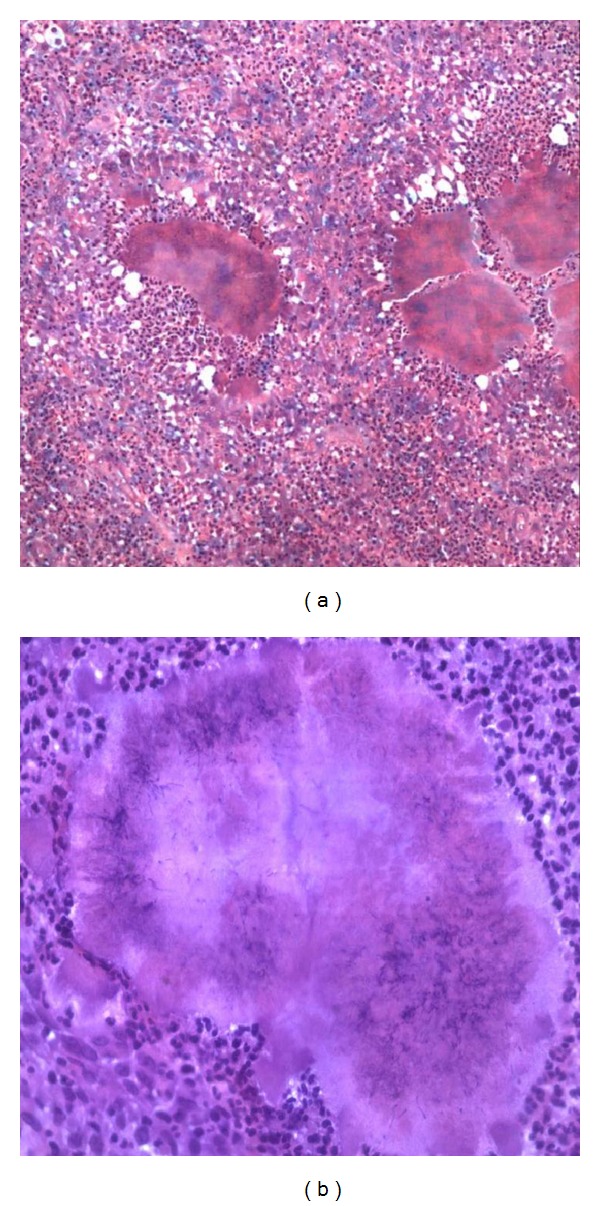

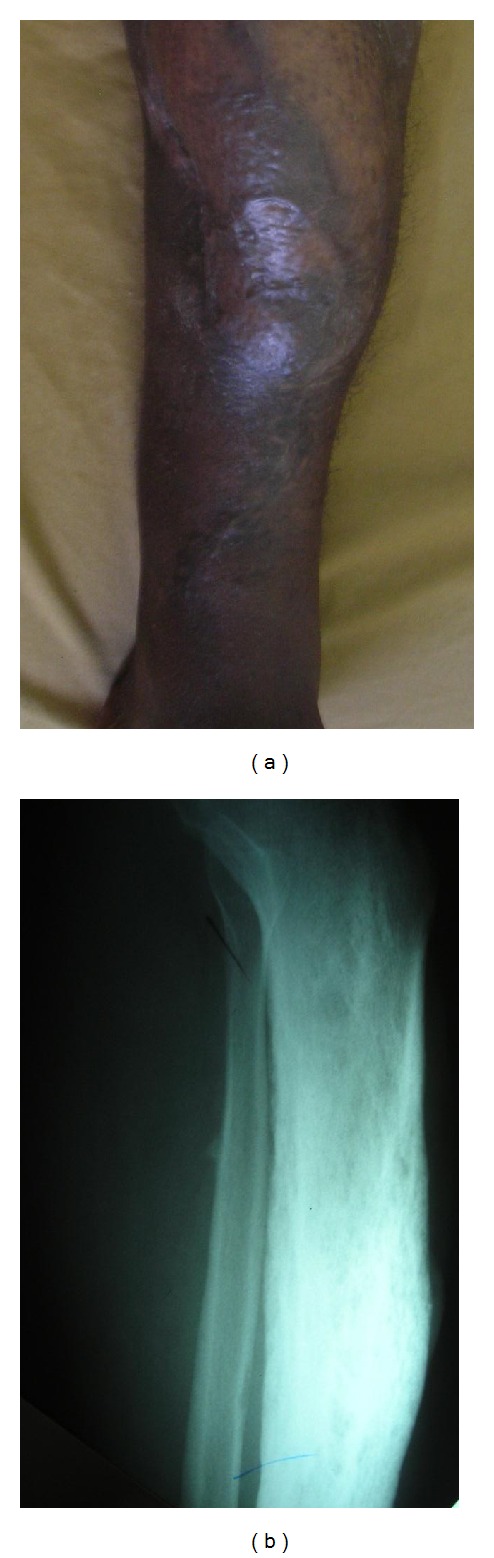

A 34-year-old nomadic patient presented to the AIC Kijabe Hospital with a left leg anteromedial swelling associated with multiple sinuses discharging yellowish granules which had developed over the previous 4 years (Figures 1(a) and 1(b)). He denied any preceding trauma. He also had lost weight over the same period. There was pain localized to the lesion and progressive inability to use the limb. The foot and ankle had normal function. He also had right testicular pain that was successfully treated as epididymo-orchitis with ciprofloxacin. Radiographs revealed tibial superficial cortical lytic defects without periosteal reaction (Figure 2). He had a normocytic, normochromic anemia (5.4 g/dL) that warranted blood transfusion (10.9 g/dL) before surgery and a leucocytosis (15,500/mm3). The HIV test was negative. An incisional biopsy revealed both actinomycetoma and eumycetoma with abscesses (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)). Definitively, excision was done with gastrocsoleus flaps and STSG filling the defect. Pre- and postoperatively he was treated with itraconazole and ciprofloxacin initially for 2.5 months then itraconazole and penicillin V for 8 months, with complete resolution (Figures 4(a) and 4(b)). After 2.5 months of treatment, the leukocytosis had resolved (7,400/mm3) and the patient was ambulant full weight-bearing. No signs of recurrence have been noted to date.

Figure 1.

(a) Gross view of left leg anteromedial swelling sparing the knee, distal leg, ankle, and foot; (b) Closer view of the swelling showing the pouting sinuses.

Figure 2.

Lateral X-ray of the left tibia-fibula showing cortical lytic defects with no periosteal reaction (‘‘moth-eaten” appearance).

Figure 3.

(a) Slide showing several clusters of mycetoma organisms surrounded by reactive zone of leucocytes (granulomas) ×10, H&E stain. (b) Closer look at a mycetoma granuloma showing the clusters of the organisms centrally and the surrounding leucocytes ×20, H&E stain.

Figure 4.

(a) shows the good take of the skin graft and gastrocsoleus flaps; the sinuses have not recurred. (b) Lateral X-ray of the left tibia-fibula showing the resolution of the lytic defects in the tibia.

3. Discussion

Mycetoma is invasive and crippling and recurrence rates after treatment are high [4]. The duration of lesions vary from a few months to years and a history of a thorn prick or trauma is available in about 25% of cases [4]. All mycetoma agents have a similar clinical appearance, but atypical presentation in 10–15%, for example, cystic mass [1]. Thus, the diagnosis is mainly clinical and identification of the specific organism is the only further task. Bacterial mycetoma can usually be managed effectively with antibacterials alone (50–80% cure rates), while infections with fungi require antifungal medication and surgery [2, 4]. Without proper treatment, mycetoma can lead to deformity, amputation, and death [2]. There is no consensus on treatment regimes that are often prolonged with numerous relapses [4]. In eumycetoma, ketoconazole or itraconazole and surgery are the regime of choice [5, 6]. For actinomycetoma, various antibiotics have been used with good reported outcomes—Septrin, dapsone, amikacin, and penicillin V. Our patient who had both Eumycetes and actinomycetes as causative agents was treated with surgery (excision) and antimicrobials (itraconazole, ciprofloxacin and penicillin V). Ketoconazole is the treatment of choice for Madurella mycetomatis (most common cause of eumycetoma in hot areas) [6]. The choice of itraconazole was due to the higher likelihood of liver toxicity with ketoconazole.

4. Conclusion

This patient presented with a solitary leg mycetoma that was in Stage C (Table 1). The previous cases at our hospital with the same stage ended up with amputations due to their diffuse nature. Therefore, the localized (albeit deep) nature mitigated against an amputation. Moreover, the presence of a functional foot and the necessary medicosurgical armamentarium saved the day. Thus, as much it presents with invasion into deeper tissues in the late stages, amputation should not always be the first choice; treatment should be individualized and guided by the causative organism [5, 6], stage of disease, and whether diffuse or localized/solitary lesion(s). This paper presents a late stage of leg mycetoma that was successfully treated with limb and function preservation.

Table 1.

Staging-classification of mycetoma: a continuum of worsening disease from Stage A to D.

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| A | Swelling, no sinuses |

| B | Woody induration with pustules/sinuses |

| C | Bone involvement on X-ray |

| D | Spread to other sites/multiple lesions |

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and the accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contribution

M. Maina followed up the patient from admission to discharge from clinic and collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data. J. Theuri collected and assisted in the interpretation of the data. Both authors performed the surgery. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Acknowledgment

The authors do acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Peter M. Nthumba in editing the paper.

Abbreviations

- AIC:

African Inland Church

- HIV:

Human immunodeficiency virus

- STSG:

Split-thickness skin graft.

References

- 1.Suneet S, Anurag K, editors. Surgical Diseases in Tropical Countries. New Delhi, India: Jaypee Brothers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lichon V, Khachemoune A. Mycetoma: a review. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 2006;7(5):315–321. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahgoob ES. Mycetoma. In: Gurrent RL, Walker DH, Weller PF, editors. Tropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Pathogens and Practice. 1st edition. New York, NY, USA: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. pp. 616–620. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajkumar SA, Angamuthu N. Multiple foot sinuses due to shizomycetes. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2005;39(2):125–126. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Develoux M, Dieng MT, Kane A, Ndiaye B. Management of mycetoma in West-Africa. Bulletin de la Societe de Pathologie Exotique. 2004;96(5):376–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodríguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Current Topics in Medical Mycology. 1995;6:47–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]