Abstract

Background

Bronchial asthma is a chronic airways disease and is considered to be one of the major health problems in the Western world. During the last decade, a significant increase in the use of β2-agonists in combination with inhaled corticosteroids has been observed. The aim of this study was to assess the appropriateness of expenditure on these agents in an asthmatic population treated in a real practice setting.

Methods

This study used data for a resident population of 635,906 citizens in the integrated patient database (Banca Dati Assistito) of a local health care unit (Milano 2 Azienda Sanitaria Locale) in the Lombardy region over 3 years (2007–2009). The sample included 3787–4808 patients selected from all citizens aged ≥ 18 years entitled to social security benefits, having a prescription for a corticosteroid + β2-agonist combination, and an ATC code corresponding to R03AK, divided into three groups, ie, pressurized (spray) drugs, inhaled powders, and extrafine formulations. Patients with chronic obstructive lung disease were excluded. Indicators of appropriateness were 1–3 packs per year (underdosed, inappropriate), 4–12 packs per year (presumably appropriate), and ≥13 packs per year (overtreatment, inappropriate).

Results

The corticosteroid + β2-agonist combination per treated asthmatic patient increased from 37% in 2007 to 45% in 2009 for the total of prescribed antiasthma drugs, and 28%–32% of patients used the drugs in an appropriate manner (4–12 packs per years). The cost of inappropriately used packs increased combination drug expenditure by about 40%, leading to inefficient use of health care resources. This trend improved during the 3-year observation period. The mean annual cost per patient was higher for powders (€223.95) and sprays (€224.83) than for extrafine formulation (€142.71).

Conclusion

Based on this analysis, we suggest implementation of better health care planning and more appropriate prescription practices aimed at optimizing use of health care resources for the treatment of bronchial asthma. The results of our study should be extended to other regional/national reference local health care units, in order to define and compare average standard costs per pathology, and consolidated through the wide sample considered.

Keywords: asthma, antiasthma drugs, general medicine, appropriateness, pharmacoeconomics, health economics

Introduction

Asthma is considered to be one of the main health care problems in the Western world. In the US, 9–12 million people were estimated to have asthma in the late 1980s, with a prevalence of around 4.2%.1 In Italy, the prevalence was estimated to be 3.3%–5.5% during the same period. More recent studies report prevalence data ranging from 4% to 7% of the general population.2–5 These large estimate ranges are partly due to the difficulty in differentiating between asthma and other medical conditions, such as chronic bronchitis, and especially chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This implies the presence of undiagnosed and therefore inadequately treated patients. The socioeconomic burden of asthma is substantial in Europe, and is strongly associated with disease severity and diminished quality of life.6 According to a study carried out in Italy,5 the average annual cost of drug treatment for an adult patient suffering from asthma is about €1434. Directs costs account for 85.6% of this amount, while the rest (14.4%) is made up of indirect costs due to loss of productivity,5 with drugs contributing 27.8% of the total annual cost. The most widely used drugs are short-acting β2-agonists (80% of patients), inhaled corticosteroids (64%), and long-acting β2-agonists (34%). Every asthmatic patient of working age loses 8 working days a year on average.4 Overall, these costs are similar to those in other industrialized countries, and are mainly due to improper use of diagnostic resources and to a lack of control of the disease.7–12

In the context of reduction and optimization of national health care expenditure, our local health care unit has developed tools for monitoring health care and drug expenditure, with the aim of controlling expenditure and assessing the achievement of targets in national and regional health care planning.13 The local/regional health service units currently have the following digital databases:

Personal detail databases containing all personal information on physicians and citizens entitled to social security benefits from the health service unit (fiscal code, date of birth, gender, district).

Pharmaceutical databases, registering the volume of expenditure relating to reimbursed drugs (so-called “fascia A” drugs, ie, essential drugs and drugs for chronic illnesses, completely paid for by the public health care system). This type of database collects all reimbursement requests issued by pharmacies. Data available in the local pharmaceutical databases include the patient’s health service code, the prescribing physician’s code, marketing authorization number, number of packs, date of prescription, and date of dispensing.

Hospital illness databases, collecting hospital admissions based on diagnosis at discharge and coded according to the International Classification of Diseases and the diagnosis recorded on the hospital discharge form. This type of database contains some administrative and clinical information on hospitalizations, such as the patient’s identifying code, dates of admission and discharge, department of admission and discharge, dates and departments of any transfer within the hospital, main diagnosis, concomitant diagnoses, condition at discharge, the assigned diagnosis-related group, and the reimbursement fee for hospitalization.

These sources and their integration are a powerful tool supporting conventional methods used in epidemiological studies.14 In this paper, we analyzed patterns in antiasthma drug use in a local health care unit, ie, Milano 2 Azienda Sanitaria Locale (ASL), in the Lombardy region in Italy, with the objective of evaluating the appropriateness and cost of treatment in a large sample of the Italian asthmatic population treated in general practice.

Materials and methods

We analyzed the prescriptions for patients using antiasthma medications (ATCR03, drugs for obstructive airway disease), with particular reference to the use of corticosteroid + β2-agonist combinations of the R03AK subgroup (adrenergics and other drugs for obstructive airway diseases). Our aim was to evaluate the cost of treatment for this disease and study the prescribing habits of general practitioners, with the aim of assessing the appropriateness and cost per patient in real practice for a population covered by a local health care unit (Milano 2 ASL) in the years 2007–2009. The appropriateness indicator chosen was the number of packs used, given that both the data sheets for these antiasthma drugs and the relevant guidelines15,16 recommend following a daily regimen in order to achieve and maintain asthma control.17 Each pack means an inhaler, that if used properly, would result in a patient requiring six (one every 2 months) or 12 packs a year (ie, about one per month), depending on the dose. Therefore, in order to assess prescribing of R03AK medications, we considered the following indicators of appropriateness:

From 1–3 packs per year (underdosed, inappropriate)

From 4–12 packs per year (presumably appropriate)

13 packs and over per year (overtreatment, inappropriate)

Indeed, prescription of over 12 packs per year of these drugs by the physician may expose the patient to side effects due to overdosing, with a consequent waste of health care resources.16 The use of fewer than four packs per year is also to be considered inappropriate, because drug treatment must be constant in order to achieve control of the disease and avoid exacerbations.17 Poor adherence to inhaled corticosteroid therapy is recognized as contributing to failure of antiasthma treatment, with a consequent increase in morbidity, mortality, and consumption of health care resources. In view of the importance of continuing drug therapy, especially in chronic diseases such as asthma, we decided to quantify the number of patients who were genuinely persistent in taking their R03 medications. To this end, we considered “persistent” with treatment to mean all patients who received at least one prescription of antiasthma drugs for 2 successive years or for 3 years.

Information sources

The integrated patient database (Banca Dati Assistito) of our local health care unit (Milano 2 ASL) was used as our statistical source. This health service unit covers the south-east area of Milan which, as of January 1, 2010, is subdivided into eight districts, and includes 57 municipalities for a resident population of 635,906 people as of December 31, 2009. Data were collected from the vital records registries of the 57 municipalities of the area served by Milano 2 ASL, where information flows update the relevant database as of December 31 of each reference year, based on a collaboration model which has been implemented by the municipal administration for years.18 The main information recorded relates to the details of medical prescriptions and health care services. The database for pharmaceutical services was the starting point of our analytic process. By studying prescriptions, it is indeed possible to identify indications and/or needs that are real, recommended, or perceived, to analyze pressures and trends in the market, and to identify different prescription profiles.13 Through integration of the various databases, a complex of factors can be attributed to each individual patient (date of birth, gender, any drug prescriptions, and any hospital stays). The final result of this process is, for the single patient, the definition of a clinical, analytical, and chronological profile, and for the cluster, the creation of a population epidemiologic database.14

Population sample and period of observation

The sample was created by considering eligible all the patients aged ≥ 18 years who received at least one prescription of ATC R03 medication for obstructive airway diseases. The period of observation for this study was 3 years (2007–2009). We started by analyzing the cohort of patients for the year 2007, ie, 39,025 subjects. We then identified and excluded patients with COPD,19 because these patients may use the same drugs as patients with asthma, and thereby create confusion. The following patients were excluded from the study:

patients exempt from any drug payment because of COPD

patients with COPD criteria observed by general practitioners (these patients were previously reported as COPD patients by general practitioners involved in other ASL research)20

patients aged over 40 years with at least one prescription for tiotropium bromide (ATC R03BB04, the active ingredient in this anticholinergic drug is indeed specific for COPD)

patients aged over 40 years in need of oxygen therapy.

After applying these criteria, the sample included 30,777 patients, or 4.83% of the ASL population (635,906 citizens). The same selection criteria were also applied for the years 2008 and 2009. Because there was no certainty that the selected sample of 30,777 patients in 2007 year were all really suffering from asthma, we decided to apply further criteria to select the patient cohort. Given that persistence with taking medication and use of specific combinations of active ingredients are important in the control of asthma symptoms,17,21 it was decided to take into consideration only patients who used the drugs for at least 2 consecutive years, and among these, only those who used one of the combinations (corticosteroid + β2-agonist) with an ATC code of R03AK (adrenergics and other drugs for obstructive lung disease), as shown in Table 1. The patients identified were then subdivided in three groups on the basis of use of the following inhaled drug combinations: pressurized (spray) drugs, inhaled powders, and extrafine formulations.

Table 1.

List of products containing the various analyzed combinations (ATC R03AK, adrenergics and other drugs for obstructive airway diseases)

| Active ingredients | Brand name | ATC | Recommended dosage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluticasone + salmeterol | 25/125 mcg/inha | 120 dose | Spray | Aliflus | R03AK06 | 2 inhalations twice/daily |

| Seretide | R03AK06 | |||||

| Fluticasone + salmeterol | 25/250 mcg/inha | 120 dose | Spray | Aliflus | R03AK06 | 2 inhalations twice/daily |

| Seretide | R03AK06 | |||||

| Fluticasone + salmeterol | 25/50 mcg/inhal | 120 dose | Spray | Aliflus | R03AK06 | 2 inhalations twice/daily |

| Seretide | R03AK06 | |||||

| Fluticasone + salmeterol | 50/100 mcg/inha | 60 doses | Powder | Aliflus Diskus | R03AK06 | 1 inhalation twice/daily |

| Seretide Diskus | R03AK06 | |||||

| Fluticasone + salmeterol | 50/250 mcg/inha | 60 doses | Powder | Aliflus Diskus | R03AK06 | 1 inhalation twice/daily |

| Seretide Diskus | R03AK06 | |||||

| Fluticasone + salmeterol | 50/500 mcg/inha | 60 doses | Powder | Aliflus Diskus | R03AK06 | 1 inhalation twice/daily |

| Seretide Diskus | R03AK06 | |||||

| Budenoside + formoterol | 160 mcg + 4.5 mcg | 120 dose | Powder | Assieme | R03AK07 | 1 or 2 inhalations twice/daily |

| Symbicort | R03AK07 | |||||

| Sinestic Turbohaler | R03AK07 | |||||

| Budenoside + formoterol | 320 mcg + 9 mcg | 60 doses | Powder | Symbicort | R03AK07 | 1 inhalation twice/daily |

| Sinestic Turbohaler | R03AK07 | |||||

| Budenoside + formoterol | 80 mcg + 4.5 mcg | 120 dose | Powder | Assieme Mite | R03AK07 | 1 or 2 inhalations twice/daily |

| Symbicort Mite | R03AK07 | |||||

| Sinestic Mite | R03AK07 | |||||

| Beclometasone + formoterol | 100/6 mcg | 120 dose | Extrafine | Formodual | R03AK07 | 1 or 2 inhalations twice/daily |

| Foster | R03AK07 | |||||

| Inuver | R03AK07 |

Abbreviations: ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System.

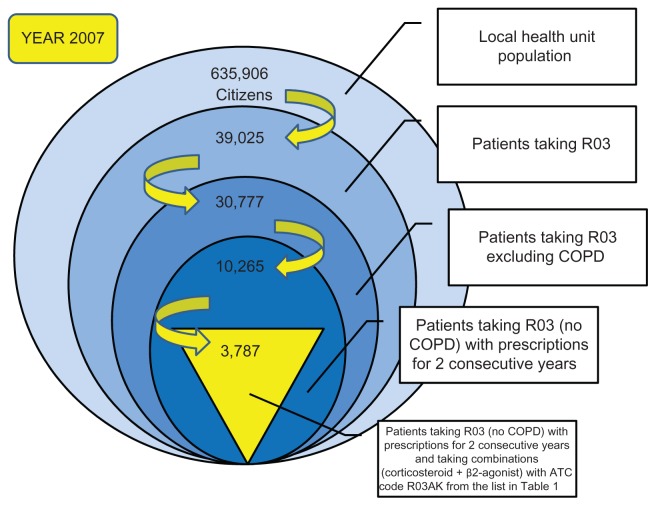

Thus, the cohort selected comprised 3787 patients suffering from asthma in 2007, with 4393 in 2008 and 4808 in 2009 (Table 2). These patients were used as the final sample for this study. Figure 1 is a schematic of the process followed to reach this number of patients for 2007; the same selection criteria were used for the subsequent 2 years. In accordance with Italian privacy law (code concerning the protection of personal data, 30 June 2003, n.196) patients were assigned identification numbers for the study, thus eliminating the patient health service codes and avoiding the risk of identifying patients personally.

Table 2.

Samples of asthmatic patients for the 2007–2009 study period

| Number of patients analyzed – total sample (*) | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| 3787 | 100% | 4393 | 100% | 4808 | 100% | |

| Number of male | 1747 | 46% | 1965 | 45% | 2190 | 46% |

| Number of female | 2040 | 54% | 2428 | 55% | 2618 | 54% |

| Number of patients Aged 18 to 40 years | 1549 | 41% | 1734 | 39% | 1894 | 39% |

| Number of patients Aged over 40 years | 2238 | 59% | 2659 | 61% | 2914 | 61% |

Note: (*) Patients taking the combinations (corticosteroid + β2-agonist – ATC code R03AK) from the list in Table 1 with prescriptions for 2 consecutive years.

Abbreviations: ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System.

Figure 1.

Terms and criteria used for selection of the study patients (year 2007).

Abbreviations: ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Results

Patient characteristics and antiasthma prescriptions

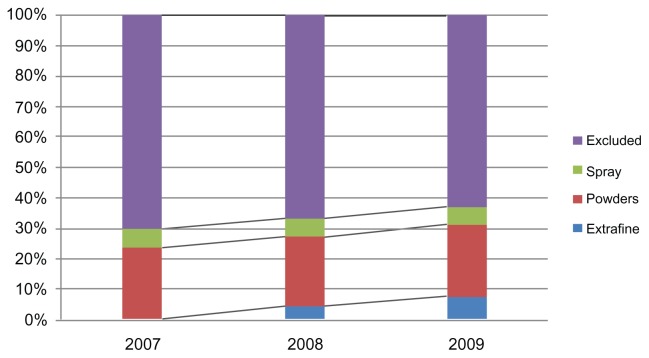

The patients identified as suffering from asthma were divided in three groups according to whether they were taking extrafine formulations, powders, or spray combinations (Table 1). We calculated the number of patients using each group of drugs and number of packs used, with their relative percentages for the years 2007–2009. Table 2 and Figures 2 and 3 show the data extracted. There was an increase in the percentage of patients using the combinations over the study period, during which the percentage went from 37% in 2007 to 45% in 2009. Antiasthma corticosteroid + β2-agonist combinations increasingly replaced other drugs, as seen in Figure 2, which shows the distribution of prescriptions for combination therapies (sprays, powders, and extrafine formulations) and other R03 drugs (excluded). Of note, the extrafine formulation was launched at the end of 2007. It is interesting that there was an increase in the use of combinations, probably due to their higher efficacy in achieving control of disease exacerbations with respect to exclusive use of drugs such as short-acting beta agonists, which are widely used as needed.10

Figure 2.

Percentages of prescriptions of R03 medications in the Milano 2 ASL in 2007–2009.

Abbreviation: ASL, Azienda Sanitaria Locale.

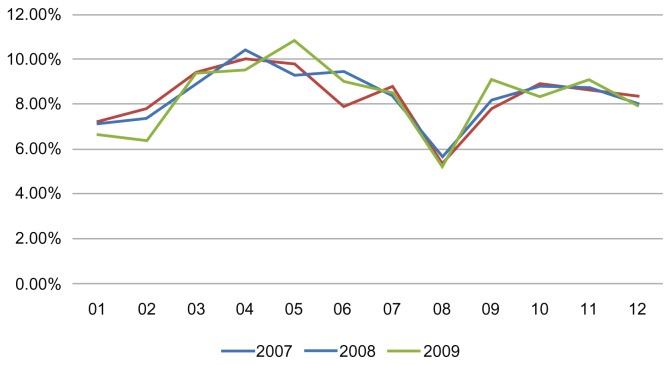

Figure 3.

Monthly distribution of drug combination prescription during the 3 years of observation.

About 54% of patients using the study drug combinations were women and 46% were men, while patients aged over 40 years comprised about 60% and patients aged 18–40 years comprised the remaining 40% (Table 2). Analysis of trends in the prescription of the study drug combinations during the year showed “prescription peaks” in the months of April–May and OctoberNovember (Figure 3), as reported elsewhere.7 It is worth noting that the prescription rate was particularly low in January. Younger patients (18–40 years) tended to use the combinations more than older patients, especially in the peak allergy months (around April), but no difference in the use of these drugs was observed between men and women.

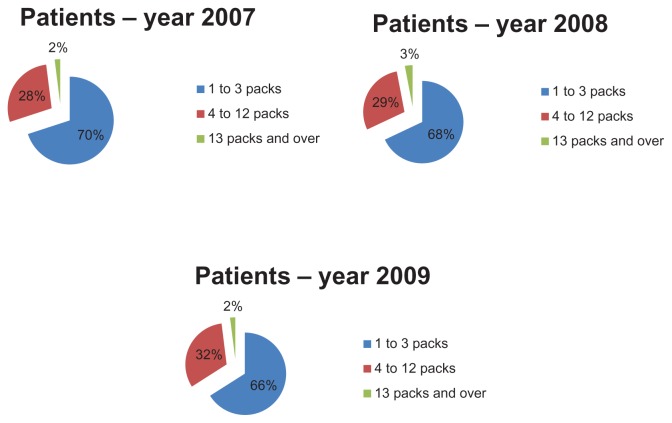

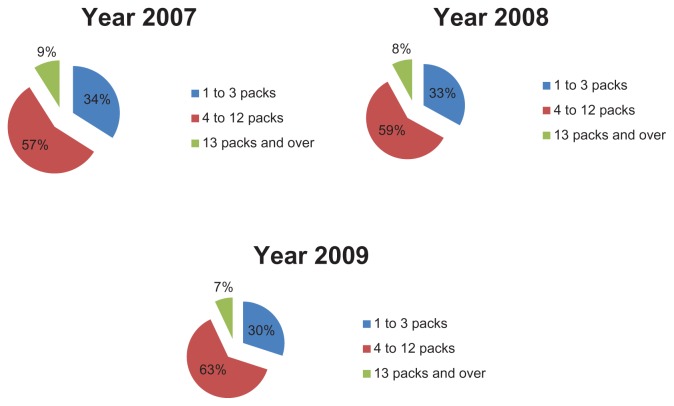

In order to evaluate therapeutic appropriateness on the basis of the indicators defined earlier, we calculated the number of packs used by each patient. In particular, we calculated the number of antiasthma drug packs used per patient and their relative percentages (ie, the number of patients taking one pack per year, those taking 2 packs per year, and so on). These data were used to construct graphs that give a more direct idea of the number of packs consumed by each patient. Figures 4 and 5 show how patients managed their therapy during the year, ie, if they use medication on a constant or occasional basis. The majority of patients (about 70% in 2007) used 1–3 packs of antiasthma medication per year; the trend is similar for the three types of drug combinations (sprays, powders, and extrafine formulations). Therefore, if we consider a drug prescription of 4–12 packs to be appropriate, it can be said that only about 28% of the asthmatic patients analyzed followed correct and appropriate treatment (Figure 4). Therefore, we can assume that a high percentage of patients (about 70%) used their medications in an inappropriate way. However, the tendency to use drug combinations in an inappropriate manner decreased slightly during the study period. The percentage of patients using 4–12 packs increased from 28% in 2007 to 32% in 2009.

Figure 4.

Assessment of prescription appropriateness: number of packs per patient in the study years.

Figure 5.

Impact of inappropriate use on expenditure. Results for the study years.

Figure 5 shows the distribution of total expenditure for drug combinations in terms of number of packs, with the aim of assessing the impact of this inappropriate use of expenditure. A high percentage (37%–43%) of the total cost for drug combinations was allocated to purchasing packs that were inappropriately consumed (ie, 1–3 packs, or over 12 packs a year). The cost of inappropriately used packs accounted for about 40% of the expenditure on drug combinations (Figure 5). However, the situation appeared to improve during the study period, with an increase in expenditure for appropriately used packs from 57% (in 2007) to 63% (in 2009).

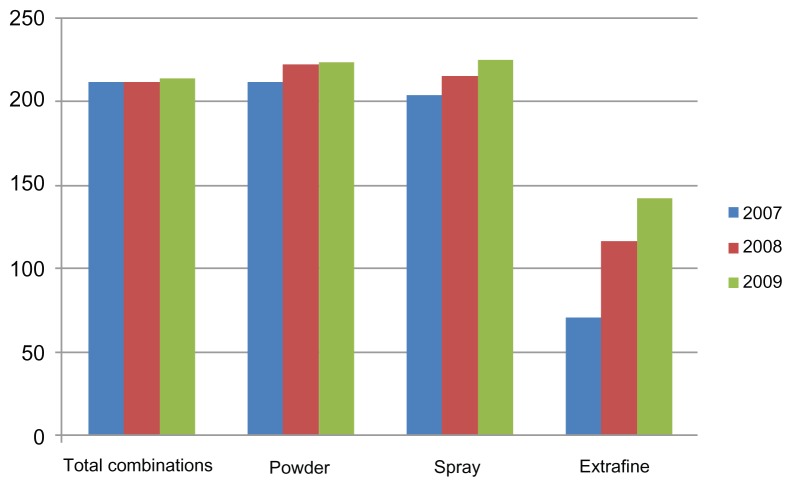

Figure 6 shows the average cost per patient during the observation period. These data indicate that powders and sprays cost more than the extrafine formulations, accounting for an average expenditure per patient of about €142.00 in 2009, when their use reached levels similar to those for the other formulations. In spite of the fact that use of extrafine formulations increased in 2009, and surpassed use of spray prescriptions, the expenditure on extrafine formulations (which have been marketed only since 2007) was equal to or even lower than that for sprays.

Figure 6.

Mean yearly cost of antiasthma drugs per patient for 2007–2009.

Discussion

Bronchial asthma is a chronic airway disorder and it is considered to be one of the major health problems in the Western world. For about 20 years, until the 1990s, the prevalence of asthma was increasing steadily in many countries, and especially in children.16 The diagnosis of asthma is made after accurate history-taking from the patient and a clinic visit, along with lung function tests including spirometry, a bronchial obstruction reversibility test, and a nonspecific bronchial challenge test.11 The decision to start regular treatment depends on the severity of asthma at the time of diagnosis, and on the frequency and severity of exacerbations. A progressive, stepwise approach to drug therapy is recommended, with selection of the best options for the individual patient based on disease severity. A significant increase in the use of β2-agonists in combination with inhaled corticosteroids was observed during the last decade. These drugs are recommended as first-line treatment for moderate to severe asthma, because they control symptoms efficiently.16 Drugs used in the treatment of asthma are also used in the treatment of obstructive airway disease (R03), which makes up about 8% of total drug expenditure by the national health care system in Italy,22 and an amount in line with that spent by the Milano 2 ASL.

Due to the importance of this disease, expenditure on its treatment, and the current need to keep public health care expenditure in check, we deemed it necessary to investigate the prescription of these drugs in terms of appropriateness and sustainability of expenditure using the real population of a local health care unit. The public health care system has been using patient databases for years, mostly for administrative purposes and to keep expenditure under control.13 The information contained in administrative databases is a byproduct of economic and/or administrative operations, and so characterizes patients as “consumers” of health care services. The main information recorded relates to medical prescriptions and health care services provided.

Assessment of drug utilization as shown in the patient database of the Milano 2 ASL allowed us to identify prescribing patterns in an important sample of the asthmatic population, to define the total and per capita costs of this disease, and to suggest policies aimed at appropriateness and optimization of expenditure by defining benchmarks between districts, physicians, different time periods, prescriptions by age and gender, and territorial spread of the disease. As regards prescription trends, we observed that combinations of corticosteroids + β2-agonists are increasingly replacing the use of single active ingredients. Furthermore, medication use varied widely during the year, with peaks in prescription of drug combinations in the months of April–May and October–November, especially in the younger population aged 18–40 years, which is in line with international research on this topic.7 This may be further evidence of correct selection of only asthmatic patients and exclusion of patients potentially suffering from COPD.

In recent years, researchers have pointed to the persistence of problems connected with drug use, such as choosing the wrong medication, incorrect duration of treatment, inadequate dosage regimens, and undertreatment.23,24 For this reason, an analysis was also carried out on the appropriateness of prescribing for this category of patients by general practitioners. Our analysis showed that about 70% of patients were using their medications inappropriately. Total packs used inappropriately comprised about 45% of the total packs used by patients in our study. About 40% of the cost to the health care system of this inappropriateness related to antiasthma combination therapy, even though the situation slightly improved during the study period. For instance, 2% of patients using over 12 packs a year have a 7% impact on the total expenditure for this type of drug treatment. Our results showed that increasing the use of extrafine formulations in these patients would have resulted in reduced expenditure, without simultaneous worsening of the health status in the treated population, because of the lower cost of these drugs, the effectiveness of which is equivalent to that of the other formulations. Indeed, in 2009, in spite of the fact that prescriptions for the extrafine formulations increased until they overtook prescriptions for sprays, expenditure on extrafine formulations remained equal or even lower than the expenditure for spray drugs.

However, it is important to highlight that use of administrative databases also implies some limitations. The data collected come directly from pharmacy invoices, meaning that they provide a true estimate of medications dispensed, but not of the actual prescriptions written by physicians. The main limitation of administrative databases is indeed the lack of clinical data; because they are created for accounting purposes, they omit data on factors such as patient lifestyle, symptoms, diagnoses, and intermediate outcome indicators, including vital signs and results of biochemical investigations. Therefore, given that patient diagnoses are not available, we cannot be completely certain that our study patients were really suffering from asthma. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the selection of the sample of asthmatic patients to be studied were based on the terms of prescription, ie, the kind of drugs used, treatment duration, need for oxygen therapy, and patient age.

In conclusion, based on the results obtained by observing medication use among asthmatic patients in the Milano 2 ASL, we can assert that there is a high level of inappropriate drug expenditure. However, it is improving, which has had a clear impact on both expenditure and patient health, given the potential for exacerbations over time. Being able to measure and understand the concept of appropriateness of therapy are not only critical to determining the effectiveness and safety of a certain drug, but they are also important for the creation of programs aimed at improving the quality of drug use. The appropriateness indicator chosen was the number of packs used, because the data sheets for these antiasthma products as well as the relevant guidelines15,16 recommend following a daily dosing regimen in order to achieve and maintain asthma control.17 The data reported here suggest that we need to define a maximum number of yearly drug combination prescriptions that can be written by general practitioners, with the recommendation that these therapies be used in a more continuous way, as is suggested in the scientific literature.16 In the light of the above results, we hope to be able to implement better health care planning and improve prescribing practices in the treatment of patients with asthma in Italy. The results of this study could be extended to other regional and/or national reference local health care units, in order to define and compare average standard costs per pathology, consolidated through the wide sample considered. Appropriate drug prescribing is of critical importance in order to achieve therapeutic objectives and to optimize use of resources by modern health care systems.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible by cooperation of the local health care unit (Milano 2 ASL), the University of Pavia School of Pharmacy, and Studi Analisi Valutazioni Economiche, a Milan-based research company, thanks to an unrestricted educational grant by Chiesi Farmaceutici, Parma.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors otherwise report no conflicts of interests in this work.

References

- 1.Evans R, Mullally DI, Wilson RW. National trends in the morbidity and mortality of asthma in the US: prevalence, hospitalization and death from asthma over two decades 1965–1984. Chest. 1987;91( Suppl):64S–65S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viegi G, Baldacci S, Vellutini M, et al. Prevalence rates of diagnosis of asthma in general population samples of Northern and Central Italy. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 1994;49:191–196. Italian. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Community Respiratory Health Survey. Prevalence of asthma and asthma symptoms in a general population sample from Northern Italy. Allergy. 1995;50:755–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1995.tb01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lucioni C, Mazzi S, Serra G, Vaghi A. The societal cost of asthma in adults in Italy. Rassegna di Patologia dell’Apparato Respiratorio. 2001;16:90–103. Italian. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dal Negro RW, Micheletto C, Tosatto R, Dionisi M, Turco P, Donner CF. Costs of asthma in Italy: results of the SIRIO (Social Impact of Respiratory Integrated Outcomes) study. Respir Med. 2007;101:2511–2519. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Accordini S, Corsico A, Cerveri I, et al. The socioeconomic burden of asthma is substantial in Europe. Allergy. 2008;63:116–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyter AC, Steinke DT. Changes in prescribing of inhaled corticosteroids (1999–2002) in Scotland. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:203–209. doi: 10.1002/pds.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman KR. Impact of ‘mild’ asthma on health outcomes: findings of a systematic search of the literature. Respir Med. 2005;99:1350–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stock S, Redaelli M, Luengen M, Wendland G, Civello D, Lauterbach KW. Asthma: prevalence and cost of illness. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:47–53. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00116203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas M, Cleland J, Price D. Database studies in asthma pharmacoeconomics: uses, limitations and quality markers. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2003;4:351–358. doi: 10.1517/14656566.4.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Amato G, Paggiaro P. Rapporto del Gruppo di Lavoro “GINA e Progetto Mondiale Asma”, adattato per il nostro Paese dal gruppo di esperti GINA – Italia 2008 [The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA)] Rassegna di Patologia dell’Apparato Respiratorio. 2008;23:254–268. Italian. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucioni C, Mangrella M, Mazzi S, Negrini C, Vaghi A. Treatment of patients with asthma with a fixed combination of budesonide and formoterol: a pharmacoeconomic evaluation vs some therapeutic alternatives. PharmacoEconomics Italian Research Articles. 2002;4:15–23. Italian. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cerra C, Lottaroli S. Utilizzo di banche dati amministrative per il calcolo dei costi di patologie croniche e/o degenerative. [Use of administrative databases for calculating the cost of chronic pathologies]. PharmacoEconomics Italian Research Articles. 2004;6:141–149. Italian. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casula M, Tragni E, Catapano AL. I database amministrativi come fonti di dati per la ricerca farmaco epidemiologica. [The administrative databases as data sources for epidemiological research drug]. CARE ICARE I. 2011:33–36. Italian. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Triggiani M, Senna G. Asthma Control Test. Uno strumento per il monitoraggio del livello di controllo e per l’ottimizzazione della terapia. [Asthma Control Test: a survey for assessing asthma control and optimizing treatment]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;16:116–121. Italian. [Google Scholar]

- 16.GINA, progetto mondiale asma 2010, Italian Guidelines. Linee guida Italiane, Modena 4–7/3/2010. [Accessed June 12, 2012]. http://www.ginasma.it. Italian.

- 17.Stempel DA, Stoloff SW, Carranza Rosenzweig JR, Stanford RH, Ryskina KL, Legorreta AP. Adherence to asthma controller medication regimen. Respir Med. 2005;99:1263–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ASL Milano 2. Il contesto: quadro epidemiologico e caratteristiche socio demografiche. Available from: http://www.aslmi2.it/web/download.nsf/91579AA161295A1686257814008092FB/$FILE/1-epidemiologia.pdf. Italian.

- 19.Global initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Italian Guidelines for COPD - Progetto mondiale BPCO 2010 - Linee guida italiane, Modena 4–7/3/2010. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/other-resources-gold-teaching-slide-set.html.

- 20.Progetto QuADRO (Qualità, Audit, Dati, Ricerca e Outcome), suppl to Il sole 24 ore sanità. Nov, 2011. Available from: http://www.sanita.ilsole24ore.com/

- 21.Bettoncelli C, Magnoni MS, Fassari C, et al. PACIS Il controllo dell’asma in italia misurato con ACT. Available from: http://www.simg.it/Documenti/Rivista/2006/06_2006/3.pdf. Italian.

- 22.AIFA, L’uso dei farmaci in Italia. Rapporto nazionale anno 2011. Available from: http://www.governo.it/GovernoInforma/Dossier/ddl_ssn/Rapporto_OSMED_2011.pdf. Italian.

- 23.Borghi C, Cicero AFG. Aderenza e persistenza in terapia, Giornale Italiano di farmacoeconomia e farmaco utilizzazione. Adherence and persistence in therapy. 2008;1(2):5–13. Italian. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Catapano AL, Casula M, Tragni E. Ndicatori di appropriatezza prescrittiva per la valutazione della qualità assistenziale. [Indicators of appropriateness for the assessment of quality of care]. CARE. 2010;6:33–35. Italian. [Google Scholar]