Abstract

Background:

The quality of sleep in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patient from India has not been studied. Aim of this study was evaluation of subjective assessment of sleep quality in stable COPD patients and its relationship with associated depression.

Materials and Methods:

Forty clinically stable COPD patients were recruited from outpatient department and their disease status was classified as per Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease guideline. Presence of depression was assessed by administering Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 and subjective quality of sleep was measured by Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).

Results:

All study subjects were male and mean age of study population was 62.2 ± 9.2 years, 12 patients (30%) in stage II, 19 patients (47.5%) in stage III and 9 patients (22.5%) in stage IV were enrolled. All subjects had poor sleep quality with the median global Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index score 11. PHQ-9 score was significantly correlated with daytime function and global PSQI score (P<0.01). No correlation of global PSQI score with severity of COPD was observed.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of poor sleep quality among COPD patients is high. Irrespective of severity of airflow obstruction, the presence of depression in COPD is a risk factor for poor sleep quality.

KEY WORDS: COPD, depression, PHQ-9, PSQI, sleep quality

INTRODUCTION

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are often associated with multiple extra pulmonary comorbidities and these comorbidities contribute to the severity of individual patients.[1] Thus, the management of COPD should not only to be concentrated on controlling respiratory symptoms, but also to be addressed the management of associated co morbidities. Polysomnographic recordings of COPD patients had demonstrated low total sleep time, frequent arousals and awakenings, reduced amounts of slow wave and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.[2] Poor quality of sleep with higher prevalence of insomnia among COPD patients are well reported.[3,4] Poor sleep quality in COPD patients are considered as consequence of multiple contributing factors e.g., higher age, severity of COPD, concomitant medications, underlying depression and any underlying sleep related breathing disorders. Depressive disorders are often associated with poor quality of sleep and thus the presence of depression in COPD may have additive effects on sleep quality. Quality of sleep is also a major determinant of health-related quality of life in COPD and their daytime of symptoms.[5] Thus, increased efforts to diagnose and to treat poor sleep quality in COPD patients may improve their quality of life.

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 is a nine-item self-report measure of depression in primary care setting. Hindi translation of PHQ-9 is well validated to assess the presence of depression in Indian population.[6] Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) is a 19-item self-rating scale designed to measure the quality of sleep during the previous month using seven components of sleep i.e., sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency and sleep disturbance, use of sleep medications and daytime dysfunction.[7] It is brief, reliable, valid and standardized self-reported measure of sleep quality. Higher PSQI scores represent worse sleep quality. To the best of our knowledge, no study from India had evaluated the effect of depression on sleep quality among COPD patients. Aim of this study was evaluation of subjective assessment of sleep quality in clinically stable COPD patients using PSQI and to assess the relationship of PSQI score with depression score and severity of airflow obstruction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective cross sectional study was carried out on consecutive clinically stable COPD patients during their outpatient department visit to collect their free medications in a tertiary care hospital in central India between January 2009 and August 2009. The subjects were recruited on the basis of written informed consent.

Subjects who were either ex or current smoker with smoking history of more than 10 pack years with post bronchodilator FEV1/FVC<0.70 and FEV1 fails to increase absolute volume >200 ml or 12% after 200 βg of salbutamol inhalation were recruited in this study. Those who had acute exacerbation of COPD in 4 weeks prior, history of depression or had other chronic systemic illness like malignancy, diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease, renal or hepatic disease were excluded from the study. All patients were on regular long or short-acting inhaled bronchodilator, inhaled steroid (fluticasone propionate and salmeterol combination, tiotropium bromide and salbutamol) and oral theophylline.

Depending on the post bronchodilator FEV1 value, the severity of COPD were classified as per global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease (GOLD) recommendation i.e., stage I (FEV1 %≥80), stage II (50%≤FEV1 %<80), stage III (30≤FEV1 %<30-49) and stage IV (FEV1 %<30).[1]

Hindi translations of PSQI and PHQ-9 questions were either self administered or recorded by a paramedical staff. The nine items of PHQ-9 were scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Total score can range from 0 to 27. Depending upon total score, the severity of depression was classified as: None (0-4), mild (5-9), moderate (10-14), moderately severe (15-19) and severe (20-27). Major depression was diagnosed if 5 or more of the 9 depressive symptom criteria were present for at least “more than half the days” in the past 2 weeks, and one of the symptoms was depressed mood or anhedonia. Other depression was diagnosed if 2, 3, or 4 depressive symptoms were present for at least “more than half the days” in the past 2 weeks, and one of the symptoms was depressed mood or anhedonia.

Each of seven components of PSQI was scored from 0 to 3, and global score of PSQI was calculated using PSQI scoring database (http://www.sleep.pitt.edu). Global PSQI score can vary from 0 to 21 and scores greater than 5 are indicative of poor sleep quality.

Data analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for data analysis. Continuous variables are presented as mean±SD and noncontinuous variables as median with inter quartile range (IQR). Bivariate relationships between the variables were assessed by the Spearman rank-correlation coefficient(r). Multivariate linear regression analysis was used to investigate the relationship between global PSQI scores and other independent variables. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

Forty COPD patients were enrolled in this study and the characteristic of the study population is shown in Table 1. There were 12 patients (30%) in stage II, 19 patients (47.5%) were in stage III and 9 patients (22.5%) in stage IV.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

Median PHQ-9 score of study population was 15 and 50% study population was suffering from major depression or other depression. Poor quality of sleep i.e., global PSQI score (>5) were observed in all cases with median PSQI global scores of study population was 11. The median time to fall asleep and median hours of sleep of study population was 20 minutes and 5 hours, respectively.

Analysis of PSQI components demonstrated that 67.5% subjects had to wake up at night or early morning (three or more times a week) and 47.5% had either breathing difficulty or cough during night (three or more times a week). Sleep medicine were never used by 90% subjects and 77.5% subjects rated their sleep quality during past month as very good or fairly good. Lack of enthusiasm over last one month was as a major problem felt by 50% of study population.

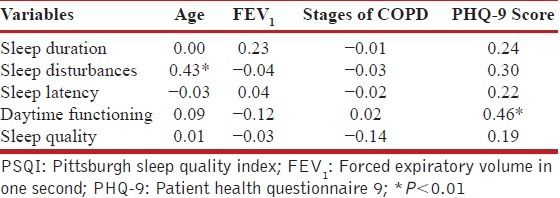

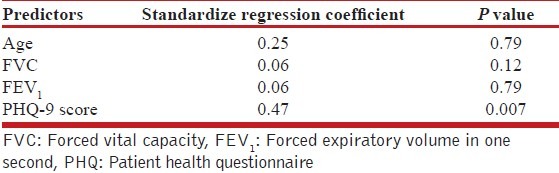

Bivariate associations between components of PSQI with age, FEV1, stages of COPD and depression score were analyzed. As shown in Table 2, a significant correlation with the daytime function and depression score (r=0.46, P<0.01) and sleep disturbance with increasing age (r=0.43, P<0.01) was observed. Age, FVC, FEV 1 and PHQ-9 scores were considered as independent variables to predict global PSQI scores. Multivariate analysis showed PHQ-9 is an independent predictor of global PSQI scoring (adjusted R square=0.16, P=0.007; Table 3).

Table 2.

Bivariate correlation of PSQI parameters with age, FEV1, stages of COPD and depression score.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of global PSQI score with age, FEV1, FVC and PHQ-9 score

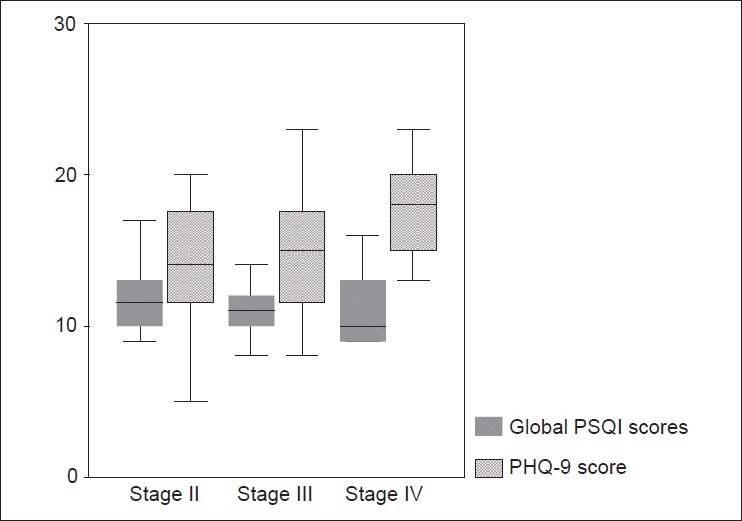

The depression scores increased with the severity of COPD, whereas global PSQI score were not different in different stages of COPD as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Box and Whisker plot of PHQ-9 and global PSQI score with severity of COPD. The boxes represent interquartile range while whisker displays the range

DISCUSSION

The extra pulmonary co-morbidities of COPD are responsible for increased morbidity among COPD patients. Prevalence of sleep disturbance in COPD patients are high and it causes nonspecific daytime symptoms of chronic fatigue, lethargy and overall impairment in quality of life.[5] Poor health related quality of life in COPD patient is an important risk factor for subsequent hospitalization and increased mortality. PSQI Index was found to an independent predictor of quality of life in COPD patients.[8] Thus, adequate diagnosis and management of sleep abnormalities in COPD patients can improve their overall sense of well being.

During sleep especially during REM, the respiratory muscle function and the responsiveness of the respiratory centre to chemical stimulants decrease. Thus COPD patients are at higher risk of developing nocturnal desaturation. Desaturation during sleep was considered as a major determinant of disturbed sleep among COPD patients. But, Lewis et al. demonstrated that isolated nocturnal desaturation (more than 30% nights with a saturation of less than 90%) in COPD were not associated with impairment of sleep quality, daytime function or health related quality of life.[9] McKeon et al., also observed that supplemental oxygen, though improve nocturnal oxygenation, does not improve the quality of sleep in COPD patients.[10] COPD patients are at higher risk of having obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and OSA related symptoms. When both the COPD and OSA occur together it is known as overlap syndrome. Patients with overlap syndrome used to have higher Epworth sleepiness scores, lower total sleep time, lower sleep efficiency, and a higher arousal index compared to those with COPD alone.[11]

Subjective quality of sleep can be assessed by administration of questionnaire, clinical interviews and sleep diaries. The objective sleep quality are obtained by polysomnography (laboratory or home based), and actigraphy. Even in mild to moderate COPD, polysmogrpahic evaluation had demonstrated low quantity and quality of sleep.[12] Sleep is largely subjective in nature and depressive symptoms are found to be strongly associated with subjective sleep quality and moderately associated with objective sleep quality.[13] Ninety percent of patients with depression complain about poor sleep quality and sleep symptoms precede an episode of depression in 40% of cases.[14] Although PSQI has not been specifically validated for COPD patients, it had widely been used to assess subjective quality of sleep in COPD patients.[5,8,9] Using a cut-off global score of 5, the PSQI has 89.6% sensitivity and 86.5% specificity for identifying “good” and “bad” sleep.[7]

Previous studies had demonstrated higher prevalence of poor sleeps quality among COPD patients. In a study of 59 moderate to severe COPD patients, Lewis et al., found that 61% had poor quality sleep (PSQI>5) irrespective of their advanced age.[9] Nunes et al., observed 70% of COPD patients in their study population had poor quality of sleep.[5] Scharf et al., evaluated 180 COPD patients and observed 71% of the patients had PSQI scores 5 with median score 12 and demonstrated that PSQI score had no relationship with GOLD classification of COPD.[8] Bellia et al., failed to observe any relationship between sleep score with insomnia complaints and severity of airflow obstruction in obstructive airway disease due to either asthma or COPD.[15] The median global PSQI scores in our study was 11 and all patients had poor quality of sleep (PSQI>5). Consistent with previous studies, we also failed to observe any significant correlation with global PSQI scores with the severity of COPD. However, we observed discrepancy between self-reported sleep quality rating and global PSQI scores and this was either due to unawareness of the subjects or subjects were habituated with poor sleep quality.

Medications used for treatment of COPD e.g., salbutamol, theophylline, ipratropium bromide can affect the sleep quality. However, studies had failed to identify any correlation with sleep quality and concurrent use of these medications in COPD.[16–18]

Even after adjusting for demographic factors, health status, and psychosocial characteristics, socio economic status is a potential predictor of PSQI score.[19] Poor socioeconomic status of COPD patient is also an independent risk factor for disease severity and functional limitation.[20] We did not assess the effect of socioeconomic status of our study population. However, all our patients were from middle to low income group and this might have additive effects for poor sleep quality.

Our study had limitations which warrant discussion. Firstly, small sample size and all the subjects were male as no female had smoking history to include in this study. As polysomnographic evaluation was not done in our study, the presence of underlying OSA can not be ruled out. Some of our subjects were illiterate and for them these questioners were readout and recorded by paramedical staff. The possibility of difference between self reported and recorded finding may be present.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated high prevalence of poor quality of sleep among Indian COPD patients and no relationship with severity of COPD and the subjective sleep quality was observed. However, the presence of depression in COPD is a risk factor for poor sleep quality and decreased daytime function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author is thankful to Mapi Institute (www.mapi-institute.com) for providing Hindi translation of PSQI questionnaires.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Global initiative for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Updated. 2010. [accessed on 2011 Feb 25]. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.com .

- 2.McNicholas WT. Sleep in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir Mon. 2006;38:325–36. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hynninen MJ, Pallesen S, Nordhus IH. Factors affecting health status in COPD patients with co-morbid anxiety or depression. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2007;2:323–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klink M, Quan SF. Prevalence of reported sleep disturbances in a general population and their relationship to obstructive airways diseases. Chest. 1987;91:540–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.91.4.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nunes DM, Mota RM, de Pontes Neto OL, Pereira ED, de Bruin VM, de Bruin PF. Impaired sleep reduces quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lung. 2009;187:159–63. doi: 10.1007/s00408-009-9147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kochhar PH, Rajadhyaksha SS, Suvarna VR. Translation and validation of brief patient health questionnaire against DSM IV as a tool to diagnose major depressive disorder in Indian patients. J Psotgrad Med. 2007;53:102–7. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.32209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buysee DJ, Reynods CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–13. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scharf SM, Maimon N, Simon-Tuval T, Bernhard-Scharf BJ, Reuveni H, Tarasiuk A. Sleep quality predicts quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;6:1–12. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S15666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis CA, Fergusson W, Eaton T, Zeng I, Kolbe J. Isolated nocturnal desaturation in COPD: Prevalence and impact on quality of life and sleep. Thorax. 2009;64:133–8. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.088930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKeon JL, Murree-Allen K, Saunders NA. Supplemental oxygen and quality of sleep in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Thorax. 1989;44:184–8. doi: 10.1136/thx.44.3.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders MH, Newman AB, Haggerty CL, Redline S, Lebowitz M, Samet J, et al. Sleep and sleep-disordered breathing in adults with predominantly mild obstructive airway disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:7–14. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2203046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valipour A, Lavie P, Lothaller H, Mikulic I, Chris Burghuber O. Sleep profile and symptoms of sleep disorders in patients with stable mild to moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Sleep Med. 2001;12:367–72. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paudel ML, Taylor BC, Diem SJ, Stone KL, Ancoli-Israel S, Redline S, et al. Association between depressive symptoms and sleep disturbances among community-dwelling older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1228–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuno N, Besset A, Ritchie K. Sleep and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1254–69. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellia V, Catalano F, Scichilone N, Incalzi RA, Spatafora M, Vergani C, et al. Sleep disorders in the elderly with and without chronic airflow obstruction: The SARA Study. Sleep. 2003;26:318–23. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Man GC, Champman KR, Ali SH, Darke AC. Sleep quality and nocturnal respiratory function with once-daily theophylline (Uniphyl) and inhaled salbutamol in patients with COPD. Chest. 1996;110:648–53. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.3.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin RJ, Bartelson BL, Smith P, Hudgel DW, Lewis D, Pohl G, et al. Effect of ipratropium bromide treatment on oxygen saturation and sleep quality in COPD. Chest. 1999;115:1338–45. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.5.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McNicholas WT, Calverley PM, Lee A, Edwards JC. Tiotropium sleep study in COPD investigators.Long-acting inhaled anticholinergic therapy improves sleeping oxygen saturation in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:825–31. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00085804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mezick EJ, Matthews KA, Hall M, Strollo PJ, Jr, Buysse DJ, Kamarck TW, et al. Influence of race and socioeconomic status on sleep: Pittsburgh Sleep SCORE project. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:410–6. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816fdf21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisner MD, Blanc PD, Omachi TA, Yelin EH, Sidney S, Katz PP, et al. Socioeconomic status, race and COPD health outcomes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:26–34. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.089722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]