Sir,

Brain death refers to the irreversible loss of cerebral and brainstem functions with the cessation of intracerebral blood flow. The recognition of brain death is important as once it is ascertained, the life supports can be withdrawn and organ harvesting can be planned.

Recommendations for the declaration of brain death proposed by America Academy of Neurology[1] mandates fulfillment of clinical criteria along with one ancillary test.

The ancillary techniques involve either measuring the neurophysiological function of the brain or measuring the cerebral blood flow. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA), computed tomography angiography (CTA), transcranial Doppler (TCD), and radionuclide perfusion tests measure the cerebral blood flow.

DSA is considered as the gold standard; however, CTA is equally efficient and noninvasive in determining brain death.

In the setting of trauma, brain death is not an uncommon occurrence; however, many cases of brain death are left unrecognized thus providing unnecessary treatment and indiscriminate use of life-supporting devices. We came across four patients with polytrauma who were diagnosed brain dead with DSA and/or CTA done for a different purpose in our department.

Two patients had severe orofacial injuries with uncontrollable bleeding, and were taken for emergency DSA. Both of them showed contrast extravasations from branches of the external carotid artery which were embolized. Incidentally, nonopacification of the bilateral internal carotid artery (ICA) was noted in one patient and nonclearance of the contrast with layering from both ICAs in the other patient, which raised the suspicion of brain death and was promptly conveyed to the treating surgeon. A subsequent clinical examination showed a positive apnea test with unresponsiveness to any external stimuli. Brain stem reflexes could not be reliably elicited in both patients as there were severe orofacial injuries. Despite the resuscitative measure, both patients died within 8 h of DSA. In the other two patients, CTA of the brain was performed for evaluation of intraventricular and subarachnoid hemorrhages as they presented in an unconscious state. CTA in both these patients revealed the nonopacification of the bilateral ICA, which raised the suspicion of brain death. A subsequent clinical examination also showed a positive apnea test with absent brain stem reflexes which confirmed brain death in both patients. Both patients died within 7 h of CTA.

The summary of imaging findings of brain death in our case series is follows:

DSA

Nonclearance and layering of the contrast from the bilateral ICA on delayed frames indicating stasis

Stasis filling of horizontal segments of bilateral middle cerebral arteries.[2]

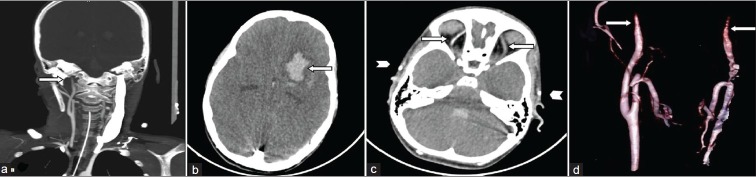

Figure 1.

DSA of a 16-year-old male patient. (a) Selective left common carotid artery (CCA) angiogram shows the opacification of only the proximal part of the ICA with distal nonfilling (arrow). (b) Selective right CCA angiogram shows nonfilling of the distal ICA (white arrow) with an active leak from the internal maxillary artery (black arrow)

CTA

Nonopacification of the bilateral ICA and intracerebral branches [Figure 2a and b]

Normal opacification of extracranial vessels such as superficial temporal arteries [Figure 2c]

Prominent bilateral superior ophthalmic vein enhancement [Figure 2c].

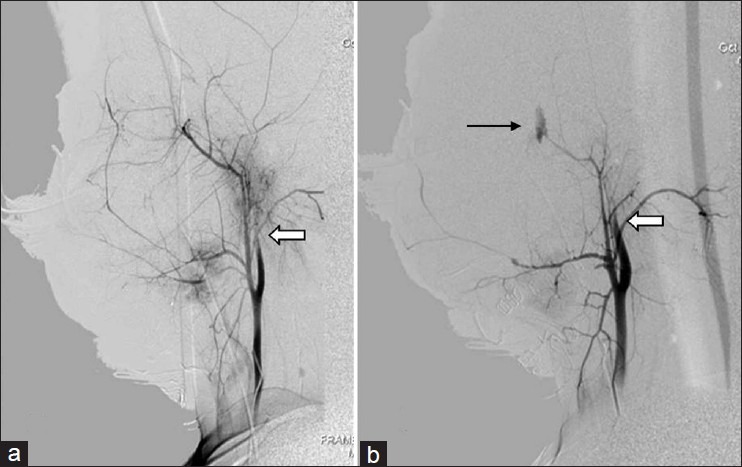

Figure 2.

CTA of a 10-year-old male patient. (a) Coronal MIP image shows the nonopacification of the bilateral ICA and intracranial arteries. (b) Axial section showing the nonopacification of intracranial arteries and left frontoparietal hematoma (arrow). (c) Axial section at the level of orbits shows bilateral prominent superior ophthalmic veins (arrow). There is normal opacification of bilateral superficial temporal arteries (arrowhead) suggestive of an adequate technique of CTA. (d) Volume rendered image showing the nonopacification of distal parts of the bilateral ICA (arrows)

The proposed cause of the nonfilling of the ICA in brain death is increased intracranial tension. The development of high resistance to the flow leads to nonopacification and/or stasis.

Though DSA is considered the gold standard,[3] it is invasive, expensive, and time consuming, and needs expertise and transfer of patients to the radiology department. CTA being noninvasive is a viable alternative. Dupas et al.[4] proposed a CTA scoring method analyzing the opacification of seven intracranial vessels. Frampas et al.[2] modified the criteria and proposed a simpler scoring system using four vessels and concluded that the four-point scoring appears highly sensitive for confirming brain death, maintaining a specificity of 100%. Being noninvasive and less time consuming, it could possibly replace DSA.[4] However, this modality is not well validated, and sensitivity also varies widely between various studies. Also, in comparison with DSA, the divergence rate was found to be 30% for CTA.[5] Moreover, as both these modalities are based on the demonstration of the absence of cerebral perfusion due to raised intracranial tension, false negative results can occur in conditions where intracranial pressure is lowered by some decompressive mechanism like craniotomy, fracture, and ventriculoperitoneal shunt, and in young infants, with open fontanalles and sutures. Both these modalities also require the administration of the contrast which may provoke allergic reactions, or renal damage, and possibly increased transplant rejection.[6] Moreover, false positive cases have also been reported for CTA.[7]

We feel that in the setting of polytrauma with a low Glasgow coma scale, the DSA/CTA when done must be carefully assessed for signs of brain death. The early recognition of brain death facilitates organ harvesting and termination of unnecessary treatment and life support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wijdicks EF, Varelas PN, Gronseth GS, Greer DM. American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline update: Determining brain death in adults: Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2010;74:1911–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e242a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frampas E, Videcoq M, de Kerviler E, Ricolfi F, Kuoch V, Mourey F, et al. CT angiography for brain death diagnosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1566–70. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vatne K, Nakstad P, Lundar T. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) in the evaluation of brain death.A comparison of conventional cerebral angiography with intravenous and intra-arterial DSA. Neuroradiology. 1985;27:155–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00343787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dupas B, Gayet-Delacroix M, Villers D, Antonioli D, Veccherini MF, Soulillou JP. Diagnosis of brain death using two-phase spiral CT. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:641–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Combes JC, Chomel A, Ricolfi F, d’Athis P, Freysz M. Reliability of computed tomographic angiography in the diagnosisof brain death. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.10.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wijdicks EF. Determining brain death in adults. Neurology. 1995;45:1003–11. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.5.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greer DM, Strozyk D, Schwamm LH. False positive CT angiography in brain death. Neurocrit Care. 2009;11:272–5. doi: 10.1007/s12028-009-9220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]