Abstract

In this report, we describe a 15-year-old Malaysian male patient with a de novo SCN1A mutation who experienced prolonged febrile seizures after his first seizure at 6 months of age. This boy had generalized tonic clonic seizure (GTCS) which occurred with and without fever. Sequencing analysis of voltage-gated sodium channel a1-subunit gene, SCN1A, confirmed a homozygous A to G change at nucleotide 5197 (c.5197A > G) in exon 26 resulting in amino acid substitution of asparagines to aspartate at codon 1733 of sodium channel. The mutation identified in this patient is located in the pore-forming loop of SCN1A and this case report suggests missense mutation in pore-forming loop causes generalized epilepsy with febrile seizure plus (GEFS+) with clinically more severe neurologic phenotype including intellectual disabilities (mental retardation and autism features) and neuropsychiatric disease (anxiety disorder).

Keywords: Anxiety disorder, GEFS+, GTCS, mental retardation, SCN1A

Introduction

Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizure plus (GEFS+) which was firstly described by Scheffer and Berkovic (1997) is a familial epilepsy syndrome characterized by heterogenous phenotypes of focal and generalized epileptic seizures and genetically heterogenous.[1–3] Individuals with GEFS+ developed febrile seizures in early childhood (less than 6 months of age) and continues beyond 6 years of age with the presence and absence of fever.[4] The clinical phenotype is variable and ranges from mild febrile seizures, febrile seizure plus (FS+) to less commonly; afebrile seizures with atonic, myoclonic, or absences seizures.[3–7] GEFS+ is genetically heterogenous with evidence of the involvement of various sodium channels; SCN1A, SCN1B, and SCN2A (encoding alpha 1, alpha 2, and beta 1 voltage-gated sodium channel subunits) and GABAA receptors; GABRG2 and GABRD subunit identified to date that cause GEFS+.[8–11] Most significant GEFS+ gene, SCN1A, accounts for more than 300 mutations associated with the broader spectrum of GEFS+ including myoclonic-astatic epilepsy, severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (Dravet syndrome), and infantile spasms.[3,7,12] A 15-year-old boy with GEFS+ harboring a novel point c.5197A > G in exon 26 of SCN1A who presented variable phenotypic expression is described.

Case Report

This 15-year-old Malay boy born to non-consanguineous healthy parents presented seizure and developmental regression. He was well until 6 months of age when he developed fever associated with one episode of seizure. Since the age of 2 years, he started to have frequent episodes of generalized tonic clonic seizures (GTCS) without fever (afebrile seizures). His general physical and neurological examination was normal. His psychological examination revealed a good space-temporal orientation and social interaction. Motor examination revealed normal strength and muscle tone in all extremities. By the age of 2 years 6 month, he had experienced approximately 10 episodes of GTCS per day with 1-hour interval between seizures, lasting 1–2 minutes. His seizures had improved with 400 mg sodium valproate and 150 mg syrup carbamazepine. The frequency of his seizures had varied from seizure free to several episodes per day. His parents had noticed that his seizures were exacerbated 5–6 am during his sleeping and at day time. Since then, he gradually experienced acute cerebellar ataxia with instability during walking and his developmental and speech gradually regressed and there were no signs of improvement. At the same time, his speech worsened from few words to bubbling. His electroencephalogram (EEG), computed tomography (CT) scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain at 8 years of age were normal. Currently, he continues to experience GTCS approximately 2–3 times every month, with abrupt onset and characterized by impairment of consciousness. Those seizures lasted about 1–2 minutes and aborted spontaneously. The doses of carbamazepine were increased to 300 mg and topiramate 25 mg was added to control the seizure, which did not decrease the frequency of the seizures. His current intellectual disabilities revealed mental retardation, developmental delay and autism features. At 11 years, he was still unable to speak with no verbal communication. His other neurological impairments included motor skills, social interaction skills, processing skills, learning, and memory. During our observations, he enjoys playing by himself and was not aware of his surroundings. His repeated EEG at 11 years of age showed abnormal record with a slowing of the background for age with absence of alpha activity, and the abnormal epileptic record showed frequent burst of epileptic discharges over both centro-parietal regions. At 15 years of age, his motor skill had improved with physiotherapy. Currently, he is able to walk without support. Unfortunately, his social skills remain poor, as he still has no social interaction. He did not attend school and his carbamazepine has been substituted to carbamazepine CR 400 mg and increased topiramate doses of 37.5 mg to reduce the symptomatology. His chromosomal karyotype showed no abnormalities (46, XY). Mutational analysis for SCN1A revealed a novel heterozygous point mutation a c.5197 A > G transition in exon 26 of SCN1A. Consequently, the mutation was considered to be a pathogenic and de novo mutation.

Discussion

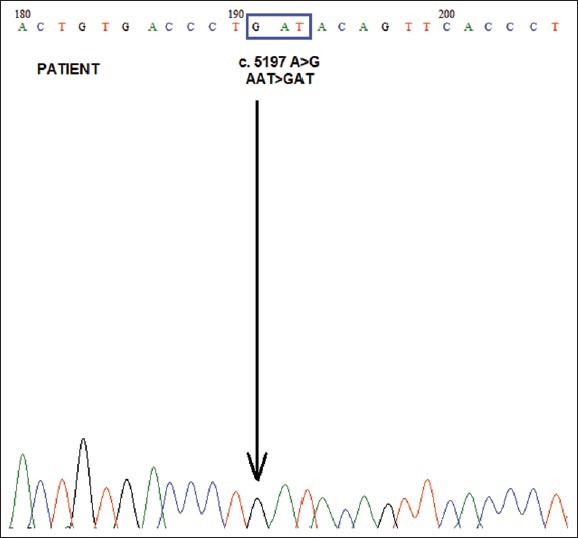

In the GEFS+ syndrome, the most common generalized epilepsy phenotypes were febrile seizure plus (FS+).[3] SCN1A is the most widely reported and clinically relevant gene for GEFS+ spectrum and also have been associated with a spectrum of epilepsy phenotype that includes severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (SMEI) and infantile spasms.[7,12] In addition to FS+, there are various generalized epilepsy phenotypes such as absences, myoclonic seizures, and myoclonic-astatic epilepsy. Here, we describe a patient with a novel de novo missense mutation (c.5197A > G) [Figure 1], which is inferred to have caused substitution of amino acid asparagines to aspartate in SCN1A. The clinical manifestation of the patient was consistent with febrile seizures and afebrile GTCS. Other clinical presentations were observed including a developmental delay, mental retardation, social anxiety and autism features.

Figure 1.

Direct DNA sequencing of SCN1A exon 26. The patient carried a c.5197A > G in SCN1A exon 26, which led to substitution of asparagines with aspartate at amino acid 1733 (P. N1733D). The arrow indicates c.5197A > G

We report a comprehensive clinical and genetic study of a patient with no history of GEFS+; our mutation analysis study revealed that our patient has a de novo heterozygous c.5197A > G transition in exon 26 SCN1A molecule (domain IV, S5-S6; N1733D), located in the functionally pore regions of SCN1A (S4-S6). Certainly, we want to highlight the identification of a novel N1733D mutation for this unfortunate patient in the loop between segments S5 and S6 in the pore-forming region of domain IV of sodium channel which is consistent with the previous findings that occurrence mutation in the pore regions of SCN1A can lead to severe epileptic phenotypes as in previous literature by Pineda-Trujillo N et al. (2005). Interestingly, this boy also had the same variants like that observed in six patients with autism.[13,14] Reported by Kanai K. et al. in 2004, the majority of mutation in the pore-forming loop regions between S5 and S6 have been identified in patients with SMEI. That previous study reported that missense mutation in the pore regions of SCN1A was associated with a more severe phenotype because of the alteration of the pore and significantly affects the function of the sodium channel.[15] The study from the French group in 2009 has brought new evidence that highly conserved amino acids located in ion transport sequences were affected by missense mutation which lead to chemical changes in amino acid and its functioning.[16]

Four other reports of missense mutation in SCN1A gene associated with GEFS+ located in the loop between segments S5 and S6 are identified to date. The first mutation was discovered by Sugawara et al. in 2001: in GEFS+ patients with febrile seizures exhibiting afebrile partial epilepsy (domain III, S5-S6;V1428, C4283T).[9] The second mutation was reported in a South American family: sequencing of the SCN1A gene revealed a novel missense mutation of aspartic acid to glycine, the amino acid replacement located in the pore-forming region of domain IV of SCN1A (domain IV, S5-S6;D1742G). The variable phenotypic expressions were observed including febrile seizures, GTCS, and mental retardation.[17] The third mutation was identified in a patient with no family history available. The patient now is 6 years old with well controlled seizures and normal neurological development (domain I, S5-S6;R377Q).[18] The fourth mutation identified by Mahoney et al. in 2009 also described a variable neurologic phenotype in a GEFS+ family that expanding the GEFS+ spectrum to include neuropsychiatric disease with a novel c1162T > C mutation in SCN1A molecule (domain I, S5-S6;Y388H).[19]

The variable expressivity observed in GEFS+ associated with SCN1A mutations remains a big challenge and interesting to discover in future. Further investigation is necessary to elucidate how the disease phenotype is determined in GEFS+ spectrum where many mechanisms, environmental factors or genetic factors could be involved in altering the sodium channel properties and function that lead to various clinical manifestation of GEFS+.[15,17] The presence of this case is important as a starting point for genetic testing in idiopathic generalized epilepsies, i.e., generalized epilepsy with febrile seizure plus (GEFS+), to prepare us for the possibility of exact diagnosis and challenges in counseling the families of the patients in future.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Ito M, Nagafuji H, Okazawa H, Yamakawa K, Sugawara T, Mazaki-Mayazaki E, et al. Autosomal dominant epilepsy with febrile seizure pluswith missense mutations of the (Na+)- channel alpha 1 subunit gene, SCN1A. Epilepsy Res. 2002;48:15–23. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(01)00313-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkovic SF, Scheffer IE. Genetics of the epilepsies. Epilepsia. 2001;42(Suppl 5):16–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.0420s5016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF. Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus. A genetic disorder with heterogeneous clinical phenotypes. Brain. 1997;120:479–90. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Escayg A, MacDonald BT, Meisler MH, Baulac S, Huberfeld G, An-Gourfinkel I, et al. Mutations of SCN1A, encoding a neuronal sodium channel, in two families with GEFS+2. Nat Genet. 2000;24:343–5. doi: 10.1038/74159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ceulemans BPGM, Claes LRF, Lagae LG. Clinical correlations of mutations in the SCN1A gene: From febrile seizures to severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;30:236–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh R, Andermann E, Whitehouse WP, Harvey AS, Keene DL, Seni MH, et al. Severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy: Extended spectrum of GEFS+ Epilepsia. 2001;42:837–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.042007837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harkin LA, McMahon JM, Iona X, Dibbens L, Pelekanos JT, Zuberi SM. The spectrum of SCN1A related infantile epileptic encephalopathies. Brain. 2007;130:843–52. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallace RH, Wang DW, Singh R, Scheffer IE, George AL, Jr, Phillips HA, et al. Febrile seizures and generalized epilepsy associated with a mutation in the Na+-channel beta1 subunit gene SCN1B. Nat Genet. 1998;19:366–70. doi: 10.1038/1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugawara T, Mizaki-Miyazaki E, Ito M, Nagafuji H, Fukuma G, Mitsudome A, et al. Nav 1.1 mutations cause febrile seizures associated with afebrile partial seizures. Neurology. 2001;57:703–5. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.4.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baulac S, Huberfeld G, Gourfinkel-An I, Mitropoulou G, Beranger A, Prud’-homme JF, et al. First genetic evidence of GABA (A) receptor dysfunction in epilepsy: A mutation in the gamma2-subunit gene. Nat Genet. 2001;28:46–8. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dibbens LM, Feng HJ, Richards MC, Harkin LA, Hodgson BL, Scott D, et al. GABRD encoding a protein for extra- or peri-synaptic GABAA receptors is a susceptibility locus for generalized epilepsies. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1315–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace RH, Hodgson BL, Grinton BE, Gardiner RM, Robinson R, Rodriguez-Casero V, et al. Sodium channel alpha1-subunit mutations in severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy and infantile spasms. Neurology. 2003;61:765–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000086379.71183.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osaka H, Ogiwara I, Mazaki E, Okamura N, Yamashita S, Iai M, et al. Patients with a sodium channel alpha 1 gene mutation show wide phenotypic variation. Epilepsy Res. 2007;75:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss LA, Escayg A, Kearney JA, Trudeau M, MacDonald BT, Mori M, et al. Sodium channels SCN1A, SCN2A and SCN3A in familial autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:186–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanai K, Hirose S, Ogunu H, Fukuma G, Shirasaka Y, Miyajima T, et al. Effect of localization of missense mutations in SCN1A on epilepsy phenotype severity. Neurology. 2004;63:329–34. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000129829.31179.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Depienne C, Trouillard O, Saint-Martin C, Gourfinkel-An I, Bouteiller D, Carpentier W, et al. Spectrum of SCN1A gene mutations associated with dravet syndrome: Analysis of 333 patients. J Med Genet. 2009;46:183–91. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.062323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pineda-Trujillo N, Carrizosa J, Cornejo W, Arias W, Franco C, Cabrera D, et al. A novel SCN1A mutations associated with severe GEFS+ in a large South American pedigree. Seizure. 2005;14:123–8. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zucca C, Redaelli F, Epifanio R, Zanotta N, Romeo A, Lodi M, et al. Cryptogenic epileptic syndromes related to SCN1A: Twelve novel mutations identified. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:489–94. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.4.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahoney K, Moore SJ, Buckley D, Alam M, Parfrey P, Penney S, et al. Variable neurologic phenotype in a GEFS+ family with a novel mutation in SCN1A. Seizure. 2009;18:492–7. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]