Abstract

Background:

Timed up and go (TUG) is a quick test used in clinical practice as an outcome measure to assess functional ambulatory mobility or dynamic balance in adults. However, little information is available on TUG test used in cerebral palsy. Hence, the purpose of our study was to assess the intra-rater reliability of TUG test in cerebral palsy children.

Aim and Objective:

To assess within–session and test-retest reliability after 1 week of TUG test in cerebral palsy children. Setting and Design: It was an a cross-sectional observational study conducted in a neurorehabilitation unit, with 30 cerebral palsy children of 4–12 years, within Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) level I, II, III, and with an IQ ≥50.The sampling technique used was purposive sampling excluding children with cognitive deficit.

Materials and Methods:

Subjects performed TUG on three occasions – Initial assessment (time 1), 30 min after initial assessment (time 2), and 1 week after initial assessment (time 3). Three trails were conducted for each of the three occasions. The mean score of three trials was documented as the final score. Within-session and test–retest reliability were analyzed using scores of time 1 and 2, and time 1 and 3, respectively.

Statistical Analysis:

The documented data were analyzed for within-session and test–retest reliability after 1 week of TUG test by using intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

Results:

Reliability of TUG test was high, with ICC of 0.99 for within-session reliability and 0.99 for test–retest reliability.

Conclusion:

Intra-rater reliability of TUG test in cerebral palsy children was found to be high.

Keywords: Cerebral palsy, intra-rater reliability, timed up and go test

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is “a group of permanent disorders of development of movement and posture, causing activity limitation, which is attributed to non-progressive disturbances occurring in developing fetal or infant brain.”[1] Common impairments are abnormal tone, posture, and movement, which limit ambulation.[1,2] Spastic diplegia is the commonest form of CP in which there is more involvement of lower than upper limb.[3,4] Timed up and go (TUG) test assesses mobility and dynamic balance in adults.[5–8] However, little information is available on TUG test used in CP.[9–14] Hence, the purpose of this study was to assess within-session and test-retest reliability after 1 week of TUG test in CP children.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional observational study to assess within-session reliability and test-retest reliability (after 1 week) of TUG test in children diagnosed as CP within the age group of 3–12 years, with preserved comprehensions, and within Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) level I, II, III.

The study was carried out at a 950-bedded tertiary care teaching hospital with well-equipped medical and surgical intensive care unit and neurorehabilitation unit.

The subjects included in this study satisfied the following inclusion criteria: diagnosed as CP within the age group of 3–12 years; with preserved comprehensions; those within GMFCS level I, II, III; and subjects having IQ ≥50. Those with cognitive deficit only were excluded from study. Based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, 40 subjects were selected. Out of these, four subjects were not willing to participate in the study and six subjects did not turn up for follow-up assessment (third assessment). Only 30 subjects could finally be studied.

Main outcome measure

Modified TUG test: Testing was conducted in rehabilitation set-up with the child's parent present.The test began with the subject sitting on a stable stool, which was selected according to the height of subjects. The stool was positioned such that it would not move when the subject moved from sitting to standing. Subject was seated with feet flat on the floor in such a way that hip and knee remained in 90° of flexion. A marking tape was used to stick star mark on the wall at a distance of 3 m from the chair.

A concrete task was used, wherein the subject was asked to touch the target (star) on the wall, instead of the more abstract verbal instructions of the standard TUG test. Abstract instructions have been shown to limit performance in children with CP.[15]

The following instructions were delivered to the subject slowly and clearly: “This test is to see how you can stand up, walk, and touch the star, then come back to sit down. The stopwatch (of cell phone) is to time you.” Subjects wore their regular footwear or orthosis, and were allowed to use walking aid, but were not allowed to be assisted by another person during the performance of the test. There was no time limit for the performance of the test, and they may stop and take rest (but not sit down) if they needed to do so. Instructions given were “After I say ‘go,’ stand up, walk up to and touch the star, and then come back and sit down. Remember to wait until I say ‘go.’ This is not a race; you must walk and not run, and I will time you. Don’t forget to touch the star, come back and sit down.” Timing was started as the child left the seat, rather than on the instruction “go” and stopped as the subject's bottom touched the seat, in order to measure “movement time” only. A practice trial was given to the subject. Thereafter, the test was conducted thrice and respective time was recorded. The time was measured in seconds. The mean of three values was documented and used for analysis. The investigator sat on a chair in clear view of the subject. Subjects were tested in small groups. Every completed TUG test was scored and noted. The same investigator conducted all the testing procedures for the study.

Modified TUG is version of TUG test , procedure for TUG test:The TUG test measure is the time taken, in seconds, by an individual to stand up from a standard arm chair, walk a distance of 3 m, turn, walk back to the chair, and sit down again.

The subject wears his/her regular footwear. If participants usually use assistive devices such as cane or walker, they should use them during the test, but this should be indicated on the data collection form. No physical assistance is given.

Setting up the test area

Determine a path free from obstruction

Place a chair with arms at one end of the path

Mark off a 3-m distance using tape.

Start the test

Speak clearly and slowly

Inform participant of the sequence and outcome

“When I say go, you will stand up from chair, walk to the mark on floor, turn around, walk back to chair and sit down.“ “I will be timing you using the stopwatch.” Ask participants to repeat the instructions to make sure they understood the instructions.

Gross motor function classification system

The GMFCS was developed by Robert Palisano, Peter Rosenbaum, Stephen Walter, Dianne Russell, Ellen Wood, and Barbara Galuppi in the year 1997 at the CanChild Centre for Childhood Disability Research. The GMFCS for CP is based on self-initiated movement with particular emphasis on sitting (trunk control) and walking. GMFCS features a 5-level ordinal scale which reflects, in a decreasing order, the level of independence and functionality of children with CP. The focus is on determining which level best represents the child's present abilities and limitations in motor function. Emphasis is on the child's usual performance at home, school, and community settings. It is therefore important to classify on ordinary performance (not best capacity) and not to include judgments about prognosis. Remember the purpose is to classify a child's present gross motor function, not to judge quality of movement or potential for improvement.

General headings for each level

Level I Walks without limitations

Level II Walks with limitations

Level III Walks using a hand-held mobility device

Level IV Self-mobility with limitations; may use powered mobility

Level V Transported in a manual wheelchair

Procedure

The synopsis of the study was submitted to the Institutional Ethical Committee (IEC) for approval. After obtaining the ethical committee approval, subjects were selected on the basis of selection criteria. The purpose of the study was explained to the subjects and they were informed about their right to opt out of the study anytime, during the course of the study, without giving reason for doing so. A written informed consent (vernacular language) was obtained from the child's parents/guardian who voluntarily agreed for inclusion of their child in the proposed study.

Performance of subjects on TUG test was observed and documented on three occasions. During each occasion, three test trails were conducted, and the mean score of the three trials was recorded for analysis.

1st occasion – Initial assessment (time 1)

2nd occasion – 30 min after the initial assessment (time 2)

3rd occasion – 1 week after the initial assessment (time 3)

For analyzing within-session reliability, the score obtained at time 1 and time 2 was considered. For analyzing test-retest reliability, the score obtained at time 1 and time 3 was considered.

Data collection

Between December 2009 and September 2010, a cross-sectional observational study was carried out in subjects with CP who fitted in the selection criteria. The performance scores of TUG test on initial assessment (time 1), 30 min after the initial assessment (time 2), and 1 week after the initial assessment (time 3) for all subjects were documented and were subjected to appropriate statistical analysis.

Data analysis

Data from all the subjects based on the performance of TUG test were entered into a computer database and analyzed with SPSS statistical package (version 14.0). The documented data were analyzed by using intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) to assess the within-session reliability and test-retest reliability after 1 week for TUG test in children. To find the mean score of TUG test with respect to GMFCS level, the mean of scores of TUG test of all the subjects within the particular GMFCS levels was calculated.

Results

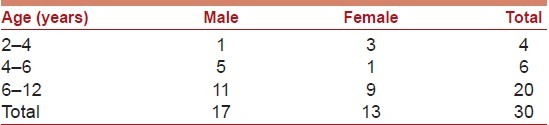

Of the 30 subjects, 17 were males and 13 were females; of these, there were 1 male and 3 females in the age group of 2–4 years. In the age group of 4–6 years, five were males and one was female. In the age group of 6–12 years, 11 were males and 9 were females. Mean age of patients was 8.16 years ±2.76 (age range 2–12 years) [Table 1, Graph 1].

Table 1.

Age and gender wise distribution of subjects

Graph 1.

Age and gender wise distribution of subjects

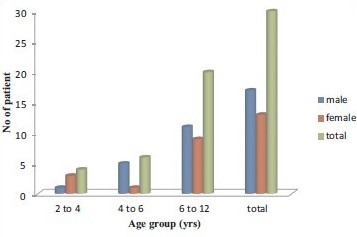

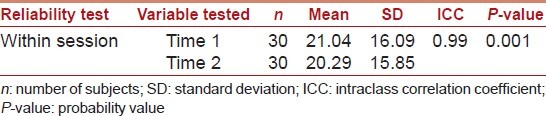

The mean score of time 1 and time 2 was 21.04 (±16.09) and 20.29 (±15.85), respectively. Within-session reliability (response stability) of TUG test (time 1 and time 2) was found to be good using ICC (0.99; P < 0.001) [Table 2, Graph 2].

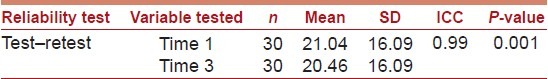

Table 2.

Within-session reliability of “timed up and go test” (using time 1 and time 2)

Graph 2.

Within-session reliability of “timed up and go test” (using time 1 and time 2)

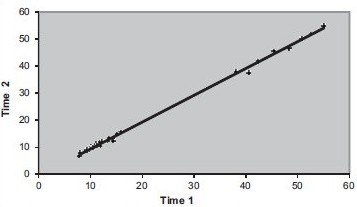

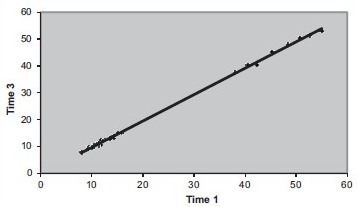

The mean score of time 1 and time 3 was 21.04 (±16.09) and 20.46 (±16.09), respectively. Test–retest reliability of TUG test (time 1 and time 3) was found to be good using ICC (0.99; P < 0.001) [Table 3, Graph 3].

Table 3.

Test–retest reliability of “timed up and go test” (using time 1 and time 3)

Graph 3.

Test–retest reliability of “timed up and go test” (using time 1 and time 3)

Discussion

The present study was carried out with the following aims: (1) To assess within-session reliability of TUG test in children diagnosed as CP and (2) to assess the test–retest reliability of TUG test in children diagnosed as CP, after 1 week.

The result of the present study indicates that the mean score of time 1, 2, and 3 was 21.04 (±16.09), 20.29 (±15.85), and 20.46 (±16.09), respectively. Reliability of the TUG test was found to be high, with ICC of 0.99 (at P < 0.001) for within-session reliability (time 1 and time 2) and 0.99 (at P < 0.001) for test-retest reliability (time 1 and time 3) in CP children of the age group 3–12 years.

The results of our study are in accordance with those of Sue-Mae Gan, Li-Chen Tung, Yue-Her Tang, and Chun-Hou Wang, who studied the intra-rater reliability of three functional balance measures, including TUG test in children with CP within GMFCS level of I–IV, wherein they concluded that TUG test had excellent test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.98–1.00).[16]

Our results are also comparable with those of Michal Katz-Leurer, Hemda Rotem, Hana Lewitus, Ofer Keren, and Shirley Meyer, who conducted a study to assess the within-session reliability of the modified functional reach test as well as TUG test in children with traumatic brain injury (TBI) and children with typical development (TD), and reported that within-session reliability for the TUG test was good in children with TBI [ICC (1,1) = 0.86] and in children with TD [ICC (1,1) = 0.85].[17]

Another study was conducted by Galea et al. (2005) to investigate the reliability and validity of TUG test in normal children and physically disabled wherein they reported that reliability of the TUG test was high, with ICC of 0.89 for within-session reliability and 0.83 for test–retest reliability in normal children of the age group 3–9 years. They also revealed that within-session reliability of the TUG test was very high (ICC = 0.99) in physically disabled children of the age group 3–19 years, which is in accordance with the results of our study.[14]

However, it is difficult to compare the results in totality with the above studies due to the difference in sample size, demographic characteristics, selection criteria, as well as the modification in TUG test.

The excellent reliability of TUG test observed in our study can be attributed to the modification of TUG test by using a concrete task wherein the subject was asked to touch the target (star) on the wall instead of the more abstract verbal instructions of the standard TUG test. Abstract instructions have been shown to limit performance in children with CP.[15]

Limitations

The limitations of our study were that the number of participants was small and the participants were a convenience sample, and therefore may not be representative of a wider population. Our sample consisted of a heterogeneous group of CP children, spread over a wide range of age, and some of the children were very young, which may have influenced the results.

Suggestion

Studies should be conducted in a larger group representative of wider population and in different age groups of CP children. Further studies in this population are recommended for establishing inter-rater reliability, concurrent validity, and responsiveness of TUG test.

Clinical implication

The TUG test is found to be a meaningful, reliable, quick, and practical objective outcome measure which can be used in clinical setting for assessing functional mobility in CP children.

Further, on establishing the responsiveness of TUG test, it can also be used to assess the efficacy of various therapeutic interventions.

CONCLUSION

We conclude that the modified TUG test has excellent within-session and test–retest reliability in children diagnosed as CP within the range of 3–12 years of age, provided that the child can understand instructions. The TUG test integrates transitions and walking skills, and provides a measure of capability that is meaningful to most people; and thus it can be used as a reliable outcome measure for assessing functional mobility in CP children.

Based on further analysis of TUG test score with respect to GMFCS level, we observed significant variation in the TUG test score for the different levels of GMFCS.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Mutch L, Alberman E, Hagberg B, Kodama K, Perat MV. Cerebral palsy epidemiology: where are we now and where are we going? Dev Med Child Neurol. 1992;34:547–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1992.tb11479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosen MG, Dickinson JC. The incidence of cerebral palsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:417–23. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)91422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson KB. Can we prevent cerebral palsy? N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1765–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb035364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuban KC, Leviton A. Cerebral palsy. N Engl J Med. 1994;33:188–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199401203300308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takarini NT, Williams EN, Denehy L. TUG in Indonesian children. Paper presented at the World Confederation of Physical Therapists Congress, Barcelona. 2003 Jun 2-12th; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson C, Grooten W, Hellsten M, Kaping K, Mattson E. Adults with cerebral palsy: Walking ability after progressive strength training. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45:220–8. doi: 10.1017/s0012162203000446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed ‘up and go’: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shumway-Cook A, Brauer S, Woollacott M. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the Timed Up & Go Test. Phys Ther. 2000;80:896–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Habib Z, Westcott S. Assessment of anthropometric factors on balance tests in children. Ped Phys Ther. 1998;10:101–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Habib Z, Westcott S, Valvano J. Assessment of balance abilities in Pakistani children: a cultural perspective. Ped Phys Ther. 1999;11:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams EN, Carroll SR. The timed up-and-go test in normal children of different ages. Paper presented at the National Paediatric Physiotherapy Conference, Sydney, Australia. 1999 Sep 7-10th; [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. WHO family of international classifications. 2001. [accessed 10th May 2005]. http://www.who.int/classification/

- 13.Morris S, Morris ME, Iansek R. Reliability of measurements obtained with the timed ‘up & go’ test in people with Parkinson disease. Phys Ther. 2001;81:810–8. doi: 10.1093/ptj/81.2.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galea MP, Phillips BA, et al. Investigation of the timed ‘Up & Go’ test in children. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2005;47:518–24. doi: 10.1017/s0012162205001027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van der Weel FR, Van der Meer AL, Lee DN. Effect of task on movement control in cerebral palsy: Implications for assessment and therapy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1991;33:419–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1991.tb14902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alison Cargeeg AM. Blackmore, Effects of circuit training for adolescents and young adults with spastic diplegia in pediatric physical therapy. 2008;20:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz-Leurer M, Rotem H, Lewitus H, Keren O, Meyer S. Functional balance tests for children with traumatic brain injury: Within-session reliability. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2008;20:254–8. doi: 10.1097/PEP.0b013e3181820dd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]