Abstract

Most bladder tumors are derived from the urothelium. Benign mesenchymal tumors are rare. Leiomyomas account for less than 0.43% of all bladder tumors. Genitourinary leiomyomata may arise in any anatomic structure containing smooth muscle. They have been reported to involve single or multiple organs. Since they may also mimic malignant lesions, they should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of any pelvic mass, with a possibility of being asymptomatic and discovered incidentally by radiographic imaging. We, herein, report a case illustrating clinical and pathological features in particular immunohistochemistry, and discuss its etiology and differential diagnosis.

Keywords: Differential diagnosis, leiyomyoma, leiyomyosarcomas

INTRODUCTION

Mesenchymal tumors of the bladder, leiomyomas in special manner, are relatively rare and heterogenous group of neoplasms arising from the mesenchymal tissues normally found in the bladder, and constitute 1-5% of all bladder neoplasms. Leiomyomas account for less than 0.43% of all bladder tumors.[1] About 250 cases of leiomyoma of the bladder have been previously reported in scientific literature in English language.[2] The incidence of leiomyoma of the bladder is approximately three times higher in women than in men.[3] Typically, it occurs in the fourth and fifth decades of life. They include leiomyoma, granular cell myoblastoma, hemangioma, lymphangioma, giant cell tumor, paraganglioma, and neurofibroma.[4] Leiomyoma is the most frequent one, and occurs mainly in young and adult females. The patients complain about nonspecific urinary symptoms or pelvic pain.[5] We present a case of benign bladder leiomyoma with typical clinical and pathological features, and discuss its possible etiopathology. The most common presenting complaints are urinary voiding symptoms such as obstruction and irritation. We describe here a case of urinary bladder leiomyoma in a middle-aged woman who did not display any urinary symptoms. Although not initially suspected, the diagnosis of urinary bladder leiomyoma was subsequently histologically confirmed.

CASE REPORT

A 49-year-old female had been hospitalized due to hepatitis in internal medicine ward. During her ultrasonographical (USG) examination, incidentally, a mass in left side wall of the bladder was revealed. The patient was referred to the urology service examination; however, there were none of the syptoms including dysuria, urgency, nocturia, incontinence, pollakiuria, macroscopic hematuria, and obstructive complaints, and nor had she any abnormality in the biochemical values. USG and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed the presence of a mass in the left side of the bladder wall without evidence to extravesical extension [Figures 1 and 2]. On cystoscopy, an intraluminally protruding solid mass, 3 cm in diameter and covered by normal bladder mucosa, was seen. Partial resection was performed with at least a 5-mm margin around the tumor. Pathological examination revealed 3×2,5×2 cm of burgundy-pink-colored leiomyoma of the bladder. The tumor was firm, had a smooth and shiny surface. The cut surface of the tumor was white-gray in color and displayed a whorled pattern. They were fixed in formalin, paraffin-embedded, and 5-mm-thick cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin; immunostains for actin-smooth-muscle (SMA) were performed using the avidinbiotin-peroxidase complex method.

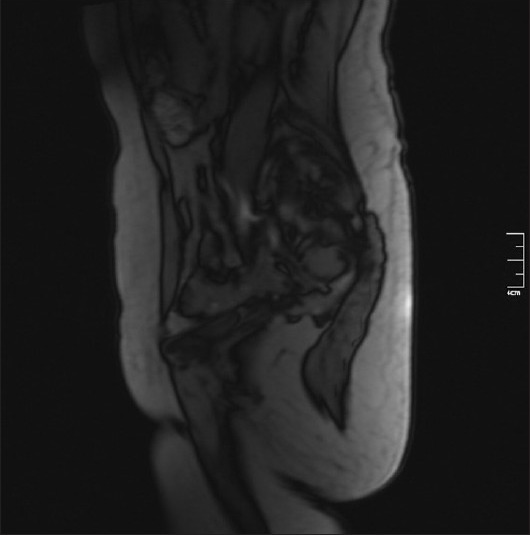

Figure 1.

MRI of the pelvis shows intraluminal polypoidal enhancing mass projecting into the bladder lumen

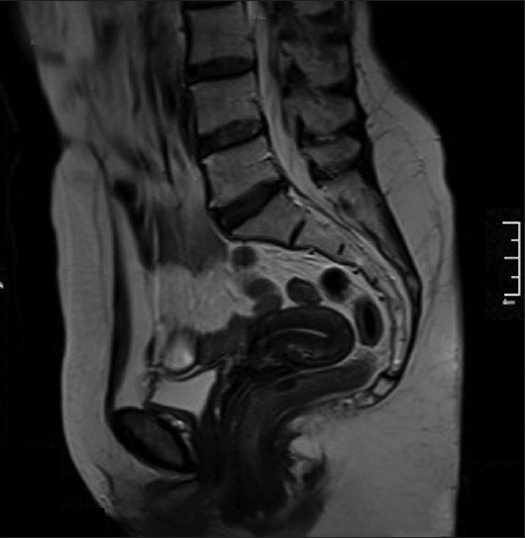

Figure 2.

MRI of the pelvis shows enhancing mass projecting into the bladder lumen (second MRI)

Microscopically, all the fragments showed the same view composed of spindle cells and fibers arranged in fascicles separated by scant hyaline stroma [Figure 3]. The nuclei of the cells were cigar-shaped and centrally located. There was no evidence of atypia, necrosis or mitosis. In a few fragments, an intact urothelial mucosa with lamina propria was seen. The spindle cells demonstrated a smooth-muscle differentiation by positive staining with SMA and negative with CD 117 [Figures 4 and 5].

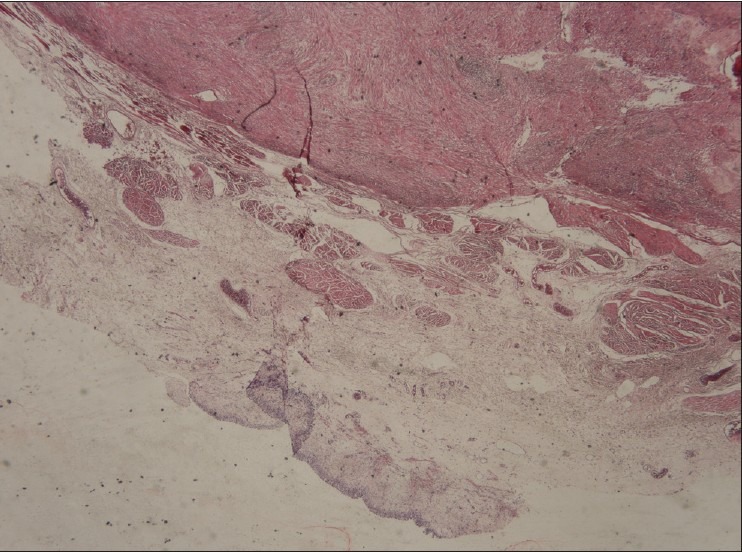

Figure 3.

Microscopically, the tumor was composed of whorled interlacing fascicles of typical smooth muscle cells without pleomorphism or mitotic figures, and the lumen was covered with urotelial epithelial cells (H and E, ×200)

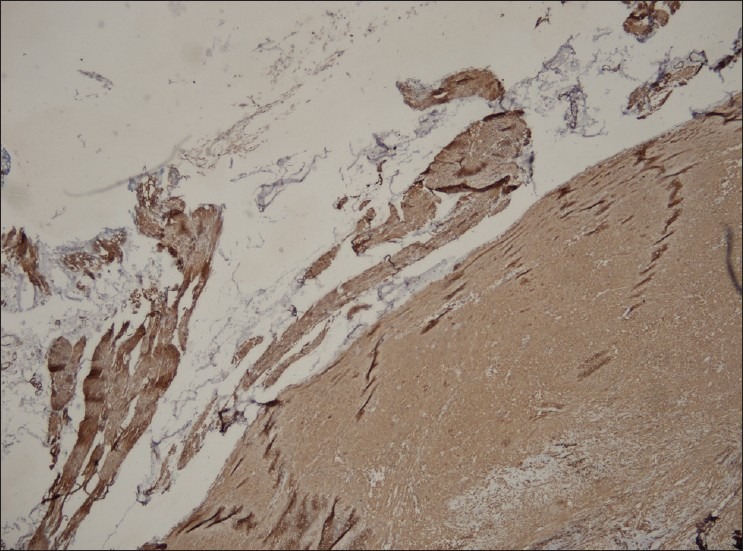

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were positive for smooth muscle actin (IHC stain, ×200)

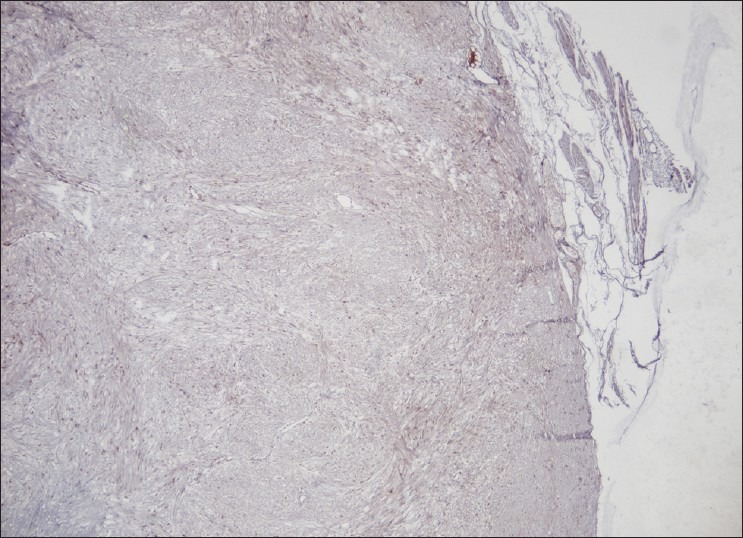

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were negative for CD117 (IHC stain, ×200)

DISCUSSION

Bladder leiomyomas show no predilection for gender or age. They can be extravesical, intramural or endovesical in location.[6] The endovesical type is present in 63%, the intramural type in 7%, and the extravesical type in 30% of the reported cases.[7] Park et al. presented endovesical lesion to all tumors.[8] Endovesical type is the most common, and is apt to cause more symptoms. However, intramural form is rare, and causes symptoms depending on its size and location. This form increases gradually in size and cause symptoms only when it reaches huge size, reported as maximum of 25 cm.[9,10] In our case, the patient was asymptomatic until the mass reached 3 cm. From a diagnostic standpoint, leiomyomas can be suspected on US and cystoscopy. However, MRI can differentiate mesenchymal tumors from the more common transitional cell tumors and even their malignant counterpart leiomyosarcoma.[10] Thus, cystoscopy and biopsy of the lesion are necessary prior to exploration. However, in the presented case, both cystoscopic and transrectal biopsies failed to put the exact diagnosis. The etiology of these tumors still remains unknown. It is proposed that leiomyomas may arise from chromosomal abnormalities, hormonal influences, bladder musculature infection, perivascular inflammation or dysontogenesis.[10,11] Leiomyomas may be asymptomatic but usually present with obstructive symptoms (49%), irritative symptoms (38%) and hematuria (11%).[10] Based on cystoscopy findings, an intramural leiomyoma can be distinguished from an endovesical tumor. Endovesical tumors refer to the submucosal growth of leiomyoma, first described by Campbell and Gislason, and are usually pedunclated or polypoid while intramural myomas are generally well-encapsulated and surrounded by bladder wall muscle.[6] The endovesical form usually causes irritative or obstructive symptoms or gross hematuria that results in detection. Intramural form, especially small tumor, may not produce symptoms as in present case.[6,11,12] The etiology of the urinary bladder leiomyoma is still inglourious. Several hypothesis have been proposed such as a hormonal-related lesion, embryonic rests’ tumor, postinflammatory myomatous metaplasia, localized infection and “wandering” fibroid resembling a parasitic uterine leiomyoma. The female predominance at a reproductive age suggests hormonal influence more than the other possibilities. Differential diagnosis prior and after intervention is essential between benign and malignant tumor when the neoplasm is poorly determined or extends beyond the wall of the bladder. Sections of the entire lesion with pushing and well-defined borders and the lack of atypia, nuclear pleomorphism, mitosis and necrosis rule-out the rare diagnosis of atypical cellular leiomyoma, or leiomyosarcoma. The latter is more frequent than leiomyoma in the wall or submucosa of the urinary bladder. Inflammatory pseudotumor and postoperative stromal tumor can be difficult to diagnose preoperatively. Since most tumors are well encapsulated, total enucleation by transurethral resection is the treatment of choice.[4]

Silva-Ramos et al. preformed a pooled analysis of 90 cases of leiomyomas. A laparotomy was performed in 56 patients (62.2%), with enucleation in 29 (32.2%), partial cystectomy in 25 (27.8%) and total cystectomy in two (2.2%). A transurethral resection was preformed in 27 (30%) and a transvaginal resection in five (5.6%). Two patients underwent conservative treatment.[13] This case was treatment partial resection . The follow-up of the cases published in the literature has shown no evidence of recurrence up to 20 years after surgery or malignant transformation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Gomez Vegas A, Silmi Moyano A, Fernandez Lucas C, Blazquez Izquierdo J, Delgado Martin JA, Corral Rosillo J, et al. Leiomyoma of the lower urinary tract. Arch Esp Urol. 1991;44:795–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saunders SE, Conjeski JM, Zaslau S, Williams J, Kandzari SJ. Leiomyoma of the urinary bladder presenting as urinary retention in the female. Can J Urol. 2009;16:4762–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chassagne S, Bernier PA, Haab F, Roehrborn CG, Reisch JS, Zimmern PE. Proposed cutoff values to define bladder outlet obstruction in women. Urology. 1998;51:408–11. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00634-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brande SD, Katz S. In: Non-epithelial tumors of the ureters and urinary bladder, in Uropathology. Hill GS, editor. Churchill Livingstone; 1989. pp. 861–72. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLukas B, Stein J. Bladder leiomyoma: A rare cause of pelvic pain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153:896. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(85)90701-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell EW, Gislason GJ. Benign mesothelial tumors of the urinary bladder: Review of literature and a report of a case of leiomyoma. J Urol. 1953;70:733–42. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)67977-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knoll LD, Segura JW, Scheithauer BW. Leiomyoma of the bladder. J Urol. 1986;136:906–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park JW, Jeong BC, Seo SI, Jeon SS, Kwon GY, Lee HM. Leiomyoma of the urinary bladder: A series of nine cases and review of the literature. Urology. 2010;76:1425–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirsh EJ, Sudakoff G, Steinberg GD, Straus FH, 2nd, Gerber GS. Leiomyoma of the bladder causing ureteral and bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol. 1997;157:1843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goluboff ET, O’Toole K, Sawczuk IS. Leiomyoma of bladder: Report of case and review of literature. Urology. 1994;43:238–41. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(94)90053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornella JL, Larson TR, Lee RA, Magrina JF, Kammerer-Doak Leiomyoma of the female urethra and bladder: Report of twenty-three patients and review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:1278–85. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70346-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen M, Lipson SA, Hricak H. MR imaging evaluation of benign mesenchymal tumors of the urinary bladder. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:399–403. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.2.9016215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva-Ramos M, Massó P, Versos R, Soares J, Pimenta A. Leiomyoma of the bladder. Analysis of a collection of 90 cases. Actas Urol Esp. 2003;27:581–6. doi: 10.1016/s0210-4806(03)72979-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]