Abstract

Purpose:

To estimate the burden of blindness and visual impairment due to cataract in Egbedore Local Government Area of Osun State, Nigeria.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty clusters of 60 individuals who were 50 years or older were selected by systematic random sampling from the entire community. A total of 1,183 persons were examined.

Results:

The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of bilateral cataract-related blindness (visual acuity (VA) < 3/60) in people of 50 years and older was 2.0% (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.6–2.4%). The Cataract Surgical Coverage (CSC) (persons) was 12.1% and Couching Coverage (persons) was 11.8%. The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of bilateral operable cataract (VA < 6/60) in people of 50 years and older was 2.7% (95% CI: 2.3–3.1%). In this last group, the cataract intervention (surgery + couching) coverage was 22.2%. The proportion of patients who could not attain 6/60 vision after surgery were 12.5, 87.5, and 92.9%, respectively, for patients who underwent intraocular lens (IOL) implantation, cataract surgery without IOL implantation and those who underwent couching. “Lack of awareness” (30.4%), “no need for surgery” (17.6%), cost (14.6%), fear (10.2%), “waiting for cataract to mature” (8.8%), AND “surgical services not available” (5.8%) were reasons why individuals with operable cataract did not undergo cataract surgery.

Conclusions:

Over 600 operable cataracts exist in this region of Nigeria. There is an urgent need for an effective, affordable, and accessible cataract outreach program. Sustained efforts have to be made to increase the number of IOL surgeries, by making IOL surgery available locally at an affordable cost, if not completely free.

Keywords: Barriers, Cataract Blindness, Nigeria, Prevalence, Surgery

INTRODUCTION

Cataract blindness presents an enormous problem in terms of magnitude,1 functional disability, loss of self-esteem,2,3 considerable economic loss, and social burden.4–6 It has been estimated that cataract accounted for 47.8% of the 37 million people who were blind worldwide in 2002.1 Age-related cataract constitutes more than 80% of all cataracts, and a large proportion of the burden is borne by elderly people who live in remote underserved rural communities of most developing countries.7 In developed and even some developing countries, declining total fertility rate and increased life expectancy result in sharp increase in the number of people aged 60 and above.8 In many of these countries, as the mean and median ages of the population increase, the prevalence of cataract and other age-related causes of blindness will increase, resulting in an increase demand for cataract surgery.9

The results from the recent national blindness and visual impairment survey revealed that 1.8% of adult Nigerians aged 40 and above had cataract-related blindness.10 However, surveys conducted earlier showed that the prevalence of cataract blindness among people aged 50 and above ranged between 2.1 and 3.8% in Northern Nigeria11–13 and 4.1% in the Niger Delta.14 It was 0.84% in South-Western Nigeria.15

Egbedore is one of the 30 Local Government Areas (LGAs) in Osun State, Nigeria. It is located in the South-Western part of Nigeria between Latitudes 07° 40” and 07° 55” N; and Longitudes 04° 20” and 04° 35” E. It covers an area of about 102 km2. It shares borders with Irepodun (north), Ede North LGA (south), Ejigbo LGA (west), and Olorunda/Osogbo LGAs (east). Awo, the headquarters of the LGA, is about 5 km from Osogbo, the Osun State capital. While other settlements such as Okinni, Ido-Osun, Ofatedo, and Olorunsogo are near to Osogbo and are peri-urban, the remaining settlements are essentially rural. The vegetation is that of the southern lowlands and tropical rain forest. The climate is mainly tropical with the long wet season stretching from March to November.16 Ophthalmic services for the LGA are provided mainly by five consultant ophthalmologists who work at Osogbo. Four of these ophthalmologists work at Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Teaching Hospital (LTH), Osogbo; one works at the General Hospital, Osogbo. All the ophthalmologists perform cataract surgeries, even though only LTH is well equipped for microsurgery. All the five ophthalmologists performed fewer than 100 cataract surgeries in 2005. A surgical eye camp has never been held in the LGA.

The aim of this study was to estimate the contribution of cataract to the burden of blindness and visual impairment in Egbedore LGA of Osun State in order to provide baseline data for developing and conducting viable cataract surgical services for the area.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a population-based cross-sectional survey that was conducted in the months of May, June, and October 2005. Persons aged 50 years and above who had resided in the LGA for at least 6 months at the time of this study formed the target population.

According to the 1991 population census data,17 the total population of Egbedore LGA was 40,293 and the annual growth rate was 3%. Although census data by sex and age group were not available for the LGA, from the national population estimates, 9.31% of the Nigerian population represented people aged 50 and above.18 Thus, the 2005 projected population of the LGA was 59,823 people, of whom 5,570 were adults aged 50 and older. The results of a population-based survey19 conducted in Egbedore LGA in 1998 indicated that 1.18% of the examined population of all age groups were bilaterally blind with visual acuity (VA) of less than 3/60. Of all blindness, 47.4% was caused by cataract. Thus, the prevalence of cataract blindness in Egbedore LGA would be 0.56%. Assuming that cataract blindness in individuals younger than 50 years is negligible, the prevalence of bilateral cataract blindness in people aged 50 and older is expected to be 0.56/9.31% = 6.01%.

We allowed for a precision of ±30% of the likely prevalence of bilateral cataract blindness, i.e., worst acceptable prevalence of 4.21% with a probability of 95%. For logistic reasons, we selected a cluster size of 60 with design effect of 1.7 for cluster random sampling. Thus, the calculated sample size using the sample size menu of Epi-info 6.04 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA) was 1,017. Allowing for a 10% non-response rate, the minimum sample size was 1,130. Thus, 20 clusters of 60 eligible subjects each were randomly selected from the community.

Clusters were selected from a census list of all settlements in the entire Egbedore LGA and their respective populations. A column with the cumulative population was added from which 20 clusters were selected through systematic random sampling. Following this procedure, clusters were selected with a probability proportional to the size of the population. The sampling method was designed to provide reliable estimates for the entire LGA. No stratification was made between rural and peri-urban settlements because there was homogeneity of the study population with respect to the risk of developing age-related cataract.

In each cluster, the starting point was selected randomly by spinning a bottle in the middle of the community and moving in the direction of the tip of the fallen bottle. All eligible subjects in all the households along that direction were enrolled until the required 60 persons had been registered. In each cluster, the local guide ensured that persons who were not members of selected households were not enrolled. Such persons were examined but were not included in the study. In clusters where fewer than 60 subjects were registered, eligible subjects were enrolled and examined from the nearest settlements to make up the required number.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Research and Ethical Committee of LTH.

The field work was carried out by a team which consisted of an ophthalmologist, three assistants (secondary school leavers) who were trained to register the subjects, measure and record VA, and record the general information section on the survey form, and a local guide for each settlement who was a member of the community.

Oral informed consent was obtained from each subject before data collection. A standard survey record form developed for Rapid Assessment of Cataract Surgical Services (RACSS)20 by the WHO Prevention of Blindness and Deafness Programme was modified and completed for each participant. The form has seven different sections: General information; vision and pinhole examination; lens examination; principal cause of vision < 6/18; history, if not examined; why cataract surgery has not been done; and details about cataract operation.

The first stage of data collection involved registration of all eligible subjects. Information obtained included name, age, sex, occupation, and educational qualifications of the subjects. During the second stage, VA was measured in each eye of subjects at 6 m in full day light, in the courtyard with available correction. Snellen illiterate “E” optotype was used for the illiterate subjects and the alphabet optotype for the literate ones. All aphakics presenting without their correction had their VA tested with +10 D lens. All eyes with presenting VA < 6/18 had their VA tested with pinhole.

In the third stage, each subject was taken inside a room or dimly-lit area for lens and fundus examination. The lens was examined with a pentorch, binocular magnifying loupe and direct ophthalmoscope at 20–30 cm. The lens was examined to determine whether it was normal, had obvious opacity, or was completely absent. The presence of intraocular lenses (IOLs) with or without posterior capsule opacification was noted. Inability to view the lens owing to the presence of dense corneal opacity, phthisis bulbi, or absent globe was also noted. Subjects with VA < 6/18 in one or both eyes with available correction or pinhole were examined further to establish the possible cause of the low vision. The posterior segments were examined with direct ophthalmoscope without dilatation because most of our subjects would not permit instillation of mydriatics into their eyes for fear of losing their sight. Intraocular pressure was measured in all subjects with suspicious discs (Cup/Disc ratio > 0.8) with the Perkins hand-held tonometer. Causes of low vision or blindness most amenable to treatment or prevention were adjudged to be the likely principal cause of problem for each eye and each subject in accordance with WHO convention.

During the last stage, subjects with operable cataract were asked why cataract surgery had not been performed. Further information was requested from those with aphakia, pseudophakia, or couched eye where and when the procedure was done, mode of payment, and whether or not they were given glasses. They also were asked whether an IOL was implanted during the surgery.

All subjects with cataracts or any other serious eye conditions were referred to LTH for treatment. Subjects with minor eye problems were given prescriptions during the survey.

OPERATION DEFINITIONS

For the purpose of this study, the following definitions were applied:

Aphakia: Status of an eye that has undergone conventional cataract surgery without implantation of an IOL.

Blindness: Presenting VA of less than 3/60 in the better eye.

Borderline postoperative outcome: Presenting postoperative VA of 6/18-6/60.

Cataract blindness: Presenting VA of less than 3/60 in an eye caused by lens opacity. A person was said to be cataract blind if both eyes met this criterion.

Couching: A traditional operative form of treating cataract which is done by using blunt or sharp instruments to dislocate the lens into the vitreous.

Good postoperative outcome: Presenting postoperative VA of 6/18 or better.

Non-response: Inability to obtain information on a subject due to either non-availability of subject or subject's refusal to co-operate. At least two attempts/visits were made to obtain information before a subject was categorized as a non-responder.

Operable cataract: Presenting VA of less than 6/60 in an eye caused by lens opacity.

Poor postoperative outcome: Presenting postoperative VA worse than 6/60.

Posterior segment disorders: Referred to diabetic retinopathy, macular degeneration, and any other posterior segment disorders.

Pseudoaphakia: Status of an eye that has undergone couching.

Pseudophakia: Status of an eye that has undergone conventional cataract surgery with implantation of an IOL.

Uncorrected aphakia: refers to an aphakic eye whose vision improves to better than 3/60 with +10 D lens.

Severe visual impairment: Presenting VA 6/60 to >3/60 in the better eye with available correction.

Visual impairment: Presenting VA 6/18 to >6/60 in the better eye with available correction.

DATA ANALYSIS

A special software program (RACSS version 1.01)20 for data entry and automatic standardized data analysis has been developed in Epi-Info version 6.04. After data entry was completed, the required level of vision (VA < 3/60, VA < 6/60, or VA < 6/18) were selected, and then the required analysis report was generated using the menu system.

By dividing the number of cataract surgeries (number of people with bilateral pseudophakia/aphakia/pseudoaphakia plus number of people with unilateral pseudophakia/aphakia/pseudoaphakia and unilateral visually significant cataract) by the sum of the number of surgeries plus the number of persons who are visually impaired from cataract, we calculated the Cataract Surgical/Couching Coverage and Cataract Intervention (surgery + couching) Coverage for persons. We also calculated Cataract Surgical/Couching Coverage and Intervention Coverage for eyes. This represents the proportion of all cataract blind people, or eyes, that have been provided with cataract surgery/couching, independent of the visual outcome. This was calculated for various levels of VA, for males and females. It indicated which proportion of the cataract blindness has been covered so far by surgery and also gave an idea about the availability and accessibility of the cataract surgical services to the population of the survey area. Means with standard deviation and odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated where appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

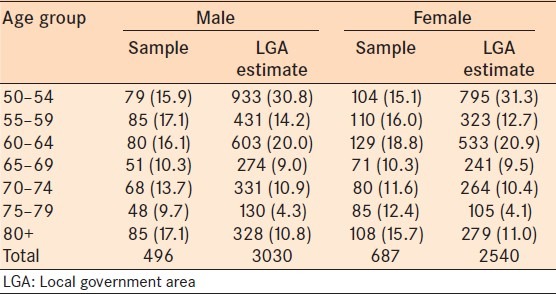

A total of 1,200 persons aged 50 and above were eligible for examination, of whom 1,183 persons (98.6%) were examined: 496 (41.9%) males and 687 females, giving a male:female ratio of 1:1.4. The age and sex distribution of the sample is presented in Table 1. The age range was 50–99 years with a mean age of 65.9 ± 11.4 years. The modal age group was 60–64 years. There was underrepresentation of people in the 50–54 years age group and slight overrepresentation of people aged 75 and above in the sample. Seventeen persons either refused or were absent during the survey period despite two repeated visits. Information about their visual status was obtained from their relatives or neighbors. These data were not included in the analysis.

Table 1.

Age group and sex distribution of sample and LGA estimates

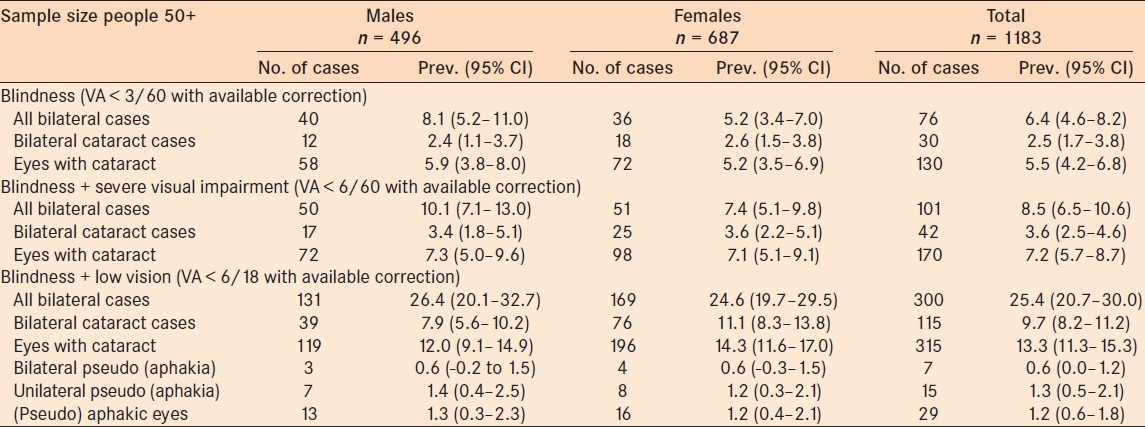

The prevalence of all-cause blindness in the sample was 6.4%. In the sample, 30 (2.5%) subjects were bilaterally blind due to cataract. Forty-two (3.6%) persons in the sample had operable cataract [Table 2]. The prevalence of cataract blindness increased with age in both sexes. There was no statistically significant gender difference in the prevalence of bilateral cataract blindness in the sample (odds ratio (OR) = 0.92 (95% CI = 0.41 – 2.03); P = 0.98).

Table 2.

Prevalence of blindness and visual impairment in the survey sample, by gender

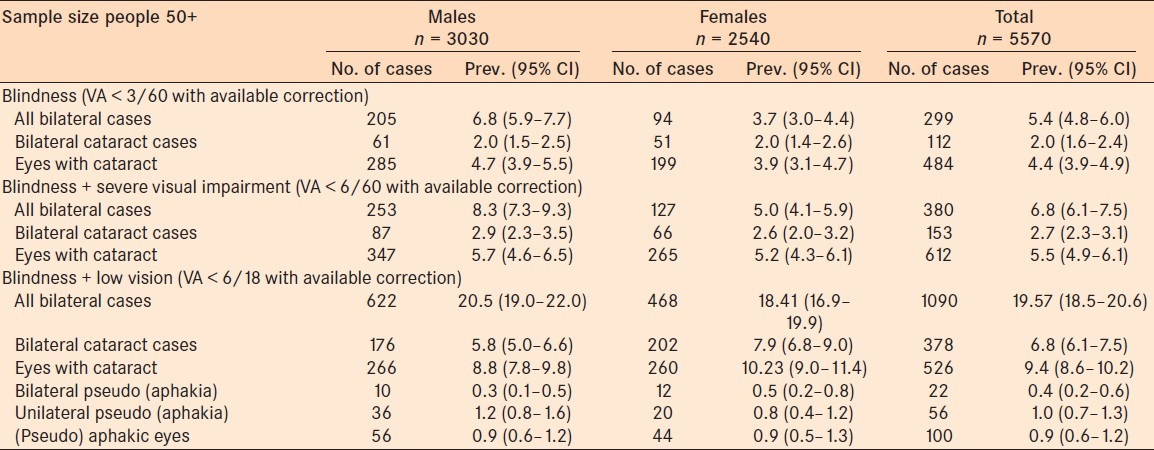

When the survey results were extrapolated to the target population in Egbedore, approximately 112 persons aged 50 and above were bilaterally blind from cataract in the LGA. In the same vein, about 484 eyes of persons aged 50 and above were blind as a result of cataract in the area. There were an estimated 612 operable cataracts among persons 50 years and older in the LGA [Table 3]. The cumulative prevalence of presenting VA < 6/18 due to cataract was 6.8% (95% CI = 6.1 – 7.5%). The age-and gender-adjusted prevalence of bilateral cataract blindness was 2.0% (95% CI = 1.6 – 2.4%) and that of bilateral operable cataract, 2.7% (95% CI = 2.3 – 3.1%).

Table 3.

Estimates of prevalence of blindness and visual impairment in Egbedore LGA, Nigeria, after applying rates observed by age and gender in a survey

The major barriers to uptake of cataract services in the area were lack of awareness (30.4%), “need not felt” (17.6%), cost of surgery (14.6%), fear (10%), “waiting for cataract to mature” (8.8%), and surgical services not available (5.8%). Others such as “no one to accompany,” fatalism, and presence of diseases making cataract surgery not feasible accounted for 12.6%.

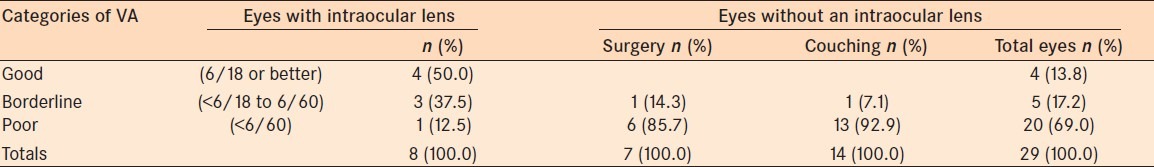

In the sample, 29 eyes of 22 persons had undergone either conventional cataract surgery or couching. Fourteen eyes (48.3%) had couching, 8 (27.6%) had IOL implants, while 7 (24.1%) had no IOL implant.

Couching was performed in unhygienic facilities as described by the patients (48.3% eyes), 24.1% had cataract surgery in government hospitals, and 13.8% each were operated in voluntary and private hospitals. Of note, no eye was operated in a surgical eye camp. Surgery was fully paid for by patients or their relations in 89.7% eyes while 10.3% eyes were operated on free of charge. More than 80% of the operated patients were not using glasses. Of all the cataract surgeries/couching, 22 (75.9%) were performed on the “first” eyes and 7 (24.1%) on the fellow eyes.

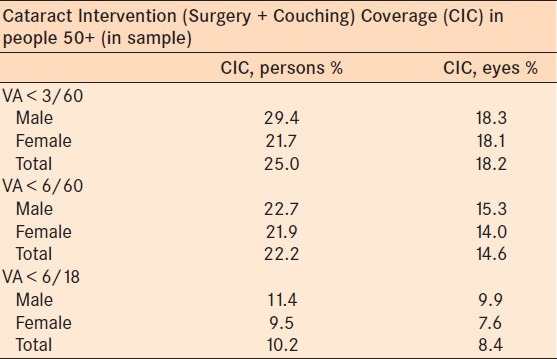

The CSC at VA < 3/60 was low; CSC (persons) and Couching Coverage (persons) had similar value of 14.3%. Cataract Intervention Coverage (CIC) for persons was 25.0% (male: 29.4%; female: 21.7%). CSC (eyes) and Couching Coverage (eyes) were 10.3 and 9.7%, respectively. The CIC (eyes) was 18.2% [Table 4]. In essence, 75% of persons with cataract in one or both eyes (and >80% of cataract blind eyes) have neither had surgery nor couching.

Table 4.

Cataract intervention coverage in Egbedore LGA, Nigeria

VA was measured in all aphakic, pseudoaphakic, and pseudophakic eyes in the sample [Table 5] to document the visual outcome after cataract surgery and couching. Eyes with IOL implants had better visual outcome than eyes without IOL implants; all the four eyes with postoperative VA ≥ 6/18 had IOL implants. With pinhole, seven eyes with IOL implants attained VA ≥ 6/18; one eye still had VA < 6/60 due to optic atrophy. Among the couched eyes, only one achieved VA = 6/18 with +10 D lens; 3 eyes had borderline outcome and 10 eyes had poor postoperative visual outcome. No improvement in VA was achieved among the eyes operated without IOL implants with either pinhole or +10 D lens. Twenty (69%) eyes had presenting VA < 6/60 (poor outcome). Cataract surgery-related complications were indicated as the cause of poor outcome in 12 (60%) eyes, posterior segment disorders in 5 (25%) eyes, and uncorrected aphakia in 3 (15%) eyes.

Table 5.

Visual acuity of eyes with or without an intraocular lens

DISCUSSIONS

Individuals who were - 50 years and older formed the target population in this study because there is a higher prevalence of age-related cataract in this age group compared to younger individuals.20 Using a lower age group, for example, 40 years old and above, would increase the sample size by 60–70% to arrive at the same level of precision,20 and this was not logistically feasible as there was only one survey team.

The survey coverage of 98.6% in this study was very high. This was made possible by the immense support given by the community leaders and the entire Egbedore people in mobilizing and encouraging eligible subjects to participate in the survey. In addition, the survey was conducted around the farming period when most of the eligible subjects were near their settlements.

The sample prevalence of bilateral cataract blindness (2.5%) and that of operable cataract of 3.6% in Egbedore LGA were higher than the National prevalence of 1.8%,10 implying that there was a huge backlog of operable cataract in the community. This is surprising in view of the fact that there are two ophthalmic centers within 60 km from the farthest village in the LGA. Studies21–23 have shown that presence of facilities do not translate automatically to utilization. In this study, lack of awareness of the existence of these facilities and poverty hampered the people from accessing the service.

High prevalence of cataract blindness with attendant low cataract surgical coverage had been reported in studies from different parts of Nigeria.11–14 The lower prevalence from Akinyele LGA15 was due to the fact that there was a good referral system between a Primary Care facility in that community and an active tertiary eye center at Ibadan. The prevalence of cataract blindness in this study was, however, lower than African estimates for individuals ≥50 years old which ranged between 4.5% and 4.95% in 2002.1 Similarly, high prevalence of cataract blindness (2.5%) was reported from Malawi24 and Zanzibar25 where uptake of cataract was as low as found in this study in spite of availability of cataract surgical service. In a similar study in rural Ethiopia,26 the prevalence of cataract blindness was as high as 3.2% despite higher cataract surgical coverage (47.8%) than Egbedore LGA. Lower prevalence of cataract blindness was, however, reported from similar studies in South-western parts of Cameroon (1%),27 Kenya (0.84%),28 Rwanda (1.2%),29 Kilimanjaro, Tanzania (1.2%),30 Pakistan (2.0%),31 Turkmenistan (0.5%),32 and Oman (0.5%)33 probably because these countries had well established and better cataract intervention programs and higher cataract surgical coverage than Egbedore LGA. Apart from differences in service uptake, the observed variations in prevalence of cataract blindness might be related to varying climatic and genetic factors in various communities; future researches might elucidate these. Most of the inhabitants of Egbedore LGA, an agrarian community, are engaged in outdoor activities most times of the day with attendant prolonged exposure to ultraviolet light rays which might increase their risk of developing cataract.

As in other related studies11–15,22,23 conducted in developing countries, lack of awareness, “need not felt,” and “cannot afford” were the most cited reason why surgery had not been done. These are followed by fear, “waiting for cataract to mature,” “surgical services not available,” and others. Ophthalmologists at Osogbo need to work in concert with the authority of the LGA to establish viable and subsidized cataract outreach program to deal with the cataract backlog in this community.

At VA < 3/60, couching was being performed in Egbedore at almost the same rate as conventional cataract surgery. This indicates that patients who were blind due to cataract consulted couchers at about the same rate as they consulted ophthalmologists for treatment of cataract. This might be due to lack of awareness of where to get conventional cataract surgery done. Conventional cataract surgery has been shown to have superior outcome over couching.34 Besides, prohibitive direct and indirect costs hamperered the cataract blind persons from accessing good quality surgeries in government and private hospitals. They therefore approached couchers who were readily available in their locality and who allowed more flexible mode of payment in cash, kind, or by installments. Additionally, the lower cost ($35 to $75 for couching vs. $125 to $160 for cataract surgery) for couching was a factor in the selection of couching. All but one couched eyes encountered during this survey had VA < 6/60 (poor outcome), whereas only one (12.5%) pseudophakic eye had a poor outcome. There is a need for public enlightenment on the drawbacks of couching. Appropriate health education on cataract, with emphasis on the availability and affordability of available cataract services, needs to be instituted in this community.

Twenty-two (75.9%) of all 29 cataract intervention procedures performed in this study were carried out on the first eyes. Most likely, the majority were so dissatisfied with the postoperative visual outcome that they considered surgery in the second eyes worthless. In addition, most of the subjects who had surgery in this study area are elderly retirees and farmers who resided in rural settlements and had little or no formal education. Therefore, the need for good binocular vision for their routine activities might not be very strong.

With 69.0% of the operated eyes unable to see 6/60, the outcomes of cataract surgery in this survey are in the same range as reported in other surveys in Nigeria11–14 and other parts of Africa.26–29 It is important to realize that these cases included eyes operated recently as well as decades earlier, by skilled as well as less skilled surgeons under optimal as well as less optimal conditions. The outcomes in the current study were worse than those reported in surveys conducted in Pakistan,31 Turkmenistan,32 Nepal,2 and China.35 The high couching rate with associated visually disabling postoperative complications and very low IOL implantation rate (27.6%) made achievement of good postoperative visual outcome almost impossible in this study area. It is comforting to note that all the five ophthalmologists at Osogbo are well trained in cataract surgery with IOL implantation. Efforts have to be made to increase the number of IOL surgeries through better utilization of available surgical facilities and making IOL surgery available locally at an affordable price. They also need to introduce self-auditing and assessments of outcomes in order to identify and address the causes of poor outcome to improve the quality of their cataract surgeries.

CONCLUSION

This study showed that more than 600 operable cataract existed among persons aged 50 and above in the study area. The existing Cataract Surgical Services only covers less than one-fifth of the need for cataract surgery. This is due to the fact that majority of the blind members of the community were unaware of the fact that their sight could be restored by surgery. A few of them could not afford the cost of surgery; those who could afford surgery were ignorant of where to obtain quality surgery. There is an urgent need for an effective, affordable, and accessible cataract outreach program in this community. The results from this survey could be very useful in starting a planning exercise involving all eye care providers in order to optimize the utilization of all eye care resources located close to the community.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We appreciate Dr. C. D. Mpyet, Dr. K. S. Oluwadiya and Dr. Asekun-Olarinmoye for their constructive criticisms. We also thank the former Chairman and the staff of the Health department of Egbedore Local Government Area for their support. The support of the survey participants and the survey team is highly appreciated.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No

REFERENCES

- 1.Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Etya’ale D, Kocur I, Pararajasegaram R, Pokharel GP, et al. Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:844–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pokharel GP, Selvaraj S, Ellwein LB. Visual function and quality of life outcomes among cataract operated and unoperated blind populations in Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:606–10. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.6.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fletcher AE, Ellwein LB, Selvaraj S, Vijaykumar V, Rahmathullah R, Thulasiraj RD. Measurements of vision function and quality of life in patients with cataracts in southern India.Report of instrument development. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:767–74. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150769013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frick KD, Foster A. The magnitude and cost of global blindness: An increasing problem that can be alleviated. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:471–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)02110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith AF, Smith JG. The economic burden of global blindness: A price too high. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:276–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.4.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rein D, Zhang P, Wirth KE, Lee PP, Hoerger TJ, McCall N, et al. The economic burden of major adult visual disorders in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1754–60. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.12.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osuntokun O. Fourth Faculty of Ophthalmology Lecture. Lagos: National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria; 2001. Blindness in Nigeria: The challenge of cataract blindness; pp. 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalache A. Ageing: A global perspective. Community Eye Health. 1999;12:1–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster A. Vision 2020: The cataract challenge. Community Eye Health. 2000;13:17–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdull MM, Sivasubramaniam S, Murthy GVS, Gilbert C, Abubakar T, Ezelum C, et al. Causes of blindness and visual impairment in Nigeria: The nigeria national blindness and visual impairment survey. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:4114–20. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabiu MM, Muhammed N. Rapid assessment of cataract surgical services in Birnin-Kebbi local government area of Kebbi State, Nigeria. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15:359–65. doi: 10.1080/09286580802399078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabiu MM. Cataract blindness and barriers to uptake of cataract surgery in a rural community of northern Nigeria. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:776–80. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.7.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ndife TI. Fellowship Dissertation. Lagos: National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria;; 2003. Rapid assessment of cataract surgical services at Giwa local government area of Kaduna State; pp. 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patrick-Ferife G, Ashaye AO, Osuntokun OO. Rapid assessment of cataract blindness among Ughelli clan in an urban/rural district of Delta State, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2005;4:52–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oluleye TS. Cataract blindness and barriers to cataract surgical intervention in three rural communities of Oyo State, Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2004;13:156–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Awo: Egbedore Local Government; 2004. Egbedore Local Government Local Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (LEEDS) 2004-2007 Handbook; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.1995 ed. Lagos: Federal Office of Statistics; 1995. Annual abstract of statistics; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abuja: National Population Commission; 1998. 1991 Population census of the Federal Republic of Nigeria: Analytical report at the national level; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adeoti CO. Prevalence and causes of blindness in a tropical African population. West Afr J Med. 2004;23:249–52. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v23i3.28132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Limburg H. World Health Organisation (WHO) Prevention of Blindness and Deafness. Geneva: World Health Organisation (WHO); 2001. Estimating Cataract Surgical Services in National Programmes. Computer software. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stock R. Distance and utilisation of health facilities in rural Nigeria. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17:563–70. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snellingen T, Shrestha BR, Gharti MP, Shrestha JK, Upadhyay MP, Pokhrel RP. Socioeconomic barriers to cataract surgery in Nepal: The South Asian cataract management study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:1424–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.12.1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson JG, Goode V, Faal H. Barriers to uptake of cataract surgery. Trop Doct. 1998;28:218–20. doi: 10.1177/004947559802800410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eloff J, Foster A. Cataract surgical coverage: Results of a population-based survey at Nkhoma, Malawi. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2000;7:219–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kikira S. Rapid assessment of avoidable blindness in Pemba and Unguja islands, Zanzibar. M.Sc. London: CEH dissertation; 2007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bejiga A, Tadesse S. Cataract surgical coverage and outcome in Goro district, Central Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2008;46:205–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oye JE, Kuper H, Dineen B, Befidi-Mengue R, Foster A. Prevalence and causes of blindness and visual impairment in Muyuka: A rural health district in South West Province, Cameroon. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:538–42. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.082271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathenge W, Kuper H, Limburg H, Polack S, Onyango O, Nyaga G, et al. Rapid assessment of avoidable blindness in Nakuru district, Kenya. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathenge W, Nkurikiye J, Limburg H, Kuper H. Rapid assessment of avoidable blindness in Western Rwanda: Blindness in a postconflict setting. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Habiyakire C, Kabona G, Courtright P, Lewallen S. Rapid assessment of avoidable blindness and cataract surgical services in Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010;17:90–4. doi: 10.3109/09286580903453514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haider S, Hussain A, Limburg H. Cataract blindness in Chakwal district, Pakistan: Results of a survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2003;10:249–58. doi: 10.1076/opep.10.4.249.15907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amansakhatov S, Volokhovskaya ZP, Afanasyeva AN, Limburg H. Cataract blindness in Turkmenistan: Results of a national survey. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:1207–10. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.11.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khandekar R, Mohammed AJ. Cataract prevalence, cataract surgical coverage and its contribution to the reduction of visual disability in Oman. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2004;11:181–9. doi: 10.1080/09286580490514487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schémann JF, Bakayoko S, Coulibaly S. Traditional couching is not an effective alternative procedure for cataract surgery in Mali. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2000;7:271–83. doi: 10.1076/opep.7.4.271.4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He M, Xu J, Li S, Wu K, Munoz SR, Ellwein LB. Visual acuity and quality of life in patients with cataract in Doumen County, China. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1609–15. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]