Abstract

Purpose:

The aim of this study is to determine the prevalence of low vision among students attending all the schools for the blind in Oyo State, Nigeria. The study set out to determine the proportion of students with low vision/severe visual impairment after best correction, to determine the causes of the low vision, to document the associated pathologies, to determine the types of treatment and visual aid devices required, and to provide the visual aids needed to the students in the schools.

Materials and Methods:

All schools students for the blind in Oyo State were evaluated between August 2007 and January 2008. All the students underwent a thorough ophthalmic examination that included measurement of visual acuity, retinoscopy and subjective refraction, tests for visual aids where indicated, and a structured questionnaire was administered.

Results:

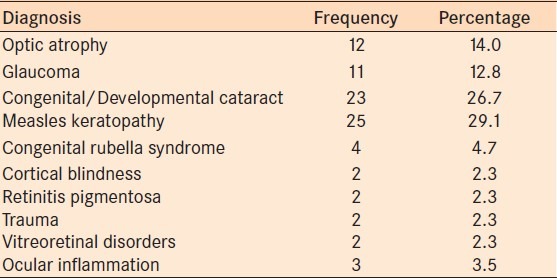

A total of 86 students were included in the study and the mean age was 19.4 ± 8.19 years. Twenty six (30%) were under 16 years of age. The most common cause of blindness was bilateral measles keratopathy/vitamin A deficiency (VAD) in 25 students (29.1%). The most common site affected was the cornea in 25 students (29.1%), the lens in 23 (26.7%), and the retina/optic nerve in 16 (18.6%). Preventable blindness was mainly from measles keratopathy/VAD (29.1%). Eleven students benefited from refraction and correction with visual aids; two having severe visual impairment (SVI), and nine having visual impairment (VI) after correction.

Conclusion:

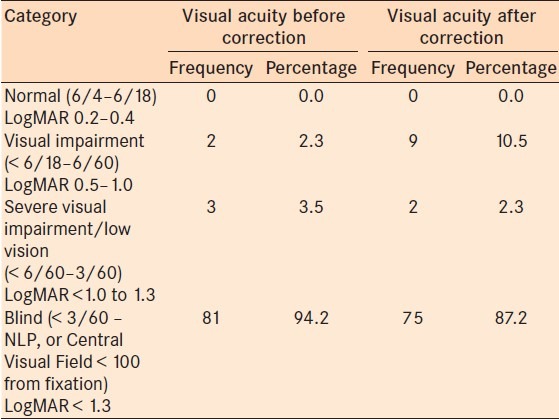

The prevalence of low vision in the schools for the blind in Oyo State is 2.3%, while the prevalence of visual impairment is 10.5%. These results suggest that preventable and treatable ocular conditions are the source of significant childhood blindness in Oyo State.

Keywords: Blind, Childhood Blindness, Low Vision, Measles Keratopathy, Oyo State, Vitamin A Deficiency

INTRODUCTION

Many of the students in schools for the blind fall below the age of 16 years (i.e., children). The provision of low vision services and low vision aids to these students with low vision, who are classified as being blind, can help enhance their residual vision and improve their quality of life. Childhood blindness is considered a priority of “Vision 2020 – The Right to Sight”.1,2 This is a global initiative for the elimination of avoidable blindness. Of the 45 million people estimated to be blind worldwide, 1.4 million are estimated to be children.3 Of this number, 1 million live in Asia and approximately 300,000 in Africa.1,2 Elimination of childhood blindness is a priority because blind children have a lifetime of blindness and deprivation ahead of them.1,2 This includes fewer opportunities for education, employment, earning potential, and social relationships.1,2 Early onset blindness can also have adverse effects on social, emotional, and psychomotor development.1,2 It is a well documented fact that blind children have a higher death rate than their sighted counterparts.1,2

An estimated 500,000 children become blind each year; 60% of the blind children in developing countries die within a year of becoming blind.1,2 Almost half of all the blindness in children in the developing countries of Africa and Asia are due to avoidable causes that can easily be treated or prevented.1,2 The prevalence of blindness is higher in developing countries because of the prevalence of potentially blinding yet avoidable conditions, which are poorly managed due to inadequate health facilities and trained medical personnel.1,2 These conditions include vitamin A deficiency (VAD), measles (which is usually related to VAD), poorly managed eye infections, and the use of harmful traditional eye medications with the sequelae of corneal opacity.1,2 Others are congenital rubella, cataract, and ophthalmia neonatorum.1,2

Facilities and skilled personnel for managing conditions that require surgery especially in the young are severely lacking in developing countries.2,3 Other causes of poor vision in these children are retinopathy of prematurity, hereditary retinal dystrophies, disorders of the central nervous system, and congenital anomalies; however, these are more common in developed countries because of the better medical facilities to treat and prevent the avoidable causes of blindness.2,3 Children that are younger than 5 years of age need to be treated as soon visual impairment is discovered to mitigate the risk of amblyopia.2,3 Correction with spectacles for refractive errors and low vision services for children with incurable visual loss should also be a priority.2,3

Though visual rehabilitation in children could be difficult, all efforts to achieve the best attainable vision are highly desirable. Multidisciplinary collaboration will be required over the long-term with comprehensive service delivery that should encompass health promotion, specific preventive measures, optical, medical, surgical services as well as low vision care, special education, and rehabilitation. Overall, this helps in improving the social status of the people involved, development of self-confidence, alleviates poverty, and reduces dependence on the community. This translates to improvement in the quality of life and attendant economic buoyancy of the community.

This study evaluated students admitted to all the schools for the blind in Oyo state, Nigeria, and determined which of these children would benefit from low vision aids that would enhance their residual vision.

RATIONALE FOR THE STUDY

The schools for the blind are filled with different categories of supposedly “blind” people. Some are legally blind in accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of blindness and deserve to be in these schools. Some have severe visual impairment; these students could benefit from visual aids that enhances their residual vision and makes them less dependent. These children could be taught to read and write without necessarily having to resort to Braille. They could learn to appreciate their surrounding and improve themselves academically, socially, occupationally, physically, and economically.

Improved vision will improve their self-confidence, give a psychological boost, and increase their employment opportunities in fields that would have otherwise been impossible for the blind.

They could be removed from the schools for the blind and be incorporated into “regular” schools. This reduces the dependence on the facilities of the schools for the blind. This will result in less dependence on the parents/guardians, and the community. Instead they could be a “bread winner” for their family/community.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

Oyo State is located in the southwestern region of Nigeria and is one of the 36 states in the country. It consists of 33 local government areas and has a population of 5.6 million people (National Population Census 2006). The major ethnic group is Yoruba, although other ethnic groups are also present in the state. Ibadan is the capital of Oyo State. Most of the people who reside in urban areas are civil servants, while those who reside in the suburban regions are civil servants, artisans, traders, and farmers. There are a total of four Schools of the Blind in Oyo State, as declared by the Oyo State Ministry of Education, Special Education Unit.

The study was carried out in all the schools of the blind in Oyo State, a list of which was obtained from the Oyo State Ministry of Education, Special Education Unit. These schools are in Ogbomosho, Oyo, Ibadan, and Eruwa.

Study design

This was a descriptive, interventional, cross-sectional study of all the students in the schools for the blind in Oyo State. A sample size was determined by using the Kish and Leslie formula for estimating a single proportion.

This is expressed as n = Zα 2pq/d2,

Where;

n = minimum sample size

Zα = standard normal deviate when α is 0.05 = 1.96

α = probability of having a type I error

p = prevalence of low vision amongst blind students in a 2003 study in eastern Nigeria = 2.4% (Ezegwui et al.)4

q = 1-p

d = level of precision = 5%

This calculation provided a minimum sample size of 36. Allowing for a nonresponse rate of 10%, the minimum sample size was 40. To cover the whole state, all the students in the schools for the blind in the state were included, the total number exceeding the calculated sample size.

Data collection procedure

Permission was obtained from the school authorities and consent was obtained from the parents of the subjects. Local ethical clearance was obtained from both the Ethical Committees of the University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan, and the Ethical Review Committee of the Oyo State Ministry of Health. The study was explained to the parents, teachers, students and school authorities, and their consent and cooperation sought.

The investigators administered and filled in the questionnaires, obtained relevant history from the students, and also noted associated disabilities. Confidentiality was ensured.

Vision was assessed by the investigator using the logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (LogMAR) charts for distance and near vision. Where this is not possible, other charts (illiterate E chart, Lea picture charts, near visual acuity charts) and the pen torch were used.

The distance visual acuity assessment was performed in well lit classrooms, and the charts were well illuminated. The students were positioned at appropriate distances away from the acuity charts (4 m from the LogMAR chart and 6 m from a Snellen chart). Each eye was assessed separately.

Vision was then assessed with a pinhole to check for any improvement in students with visual impairment. Acuity for near vision was assessed with Near Charts placed about 25 cm away from the eye. Each eye was assessed separately. Inability to read or identify symbols or pictures was followed by attempting to assess vision by count fingers, hand movement, or light perception.

Students whose vision improved with pinhole, underwent retinoscopy by the investigators (for best corrected vision), followed by subjective refraction. Crayola® colored crayons were used for color identification.

The anterior segments were examined by the investigators with a pen torch in well illuminated classrooms. The posterior segments were then examined with the direct and/or indirect ophthalmoscope where appropriate with the pupils widely dilated with either the phenylephrine hydrochloride drops or tropicamide 1% drops.

Intraocular pressure was obtained by the investigator with a hand held Perkins® tonometer; using tetracaine hydrochloride 0.5% anesthetic drops and fluorescein dye. Students with severe visual impairment or visual impairment had low vision assessment using telescopes, hand held, and stand magnifiers. Based on the best corrected vision, the students were classified into the following categories of visual acuities: blind, severe visual impairment (SVI) or low vision, visual impairment (VI), and normal as defined by WHO.

Low vision: Refers to patients with the best corrected vision in the better eye of less than 6/60 (LogMAR 1.0) and equal to or better than 3/60 (LogMAR 1.3) on the Snellen's Chart, or a visual field less than 10 degrees from the point of fixation, for which treatment is not possible, but who use, or are potentially able to use, vision for the planning and/or execution of tasks for which vision is essential.

Blindness: Is visual acuity worse/less than 3/60 or < LogMAR 1.3 (including light perception and nil light perception) in the better eye with the best corrected vision.

Visual impairment:This is best corrected visual acuity in the better eye of between 6/18 and 6/60 (Snellen's) or 0.5–1.0 (LogMAR).

Normal vision:is between 6/4 and 6/18 (Snellen's) or 0.1–0.5 (LogMAR).

The format used by the investigators in the examination and categorization of the students studied in the schools for the blind in Oyo State was fashioned using the WHO/PBL Eye Examination Record for Children with Blindness and Low Vision (ERCB),5 which was developed by the WHO Program for the Prevention of Blindness with the International Centre for Eye Health, a WHO collaborating center.

The investigators then counseled the students and the teachers. Low vision aids were issued to those whose vision improved with them. The teachers were taught how to use low vision aids and they were advised to encourage the low vision students to use the devices. Those students with treatable conditions were promptly referred to UCH, Ibadan.

Data management and analysis

Data were checked for errors by the investigators. It was then entered into SPSS version 10 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) statistical packages. Variables were summarized using means and standard deviation for quantitative variables and frequencies and proportions for qualitative variables.

Distribution of the types of blindness, causes, associated pathologies, and types of visual aid devices needed were summarized by the investigators using proportions. The relationship between low vision and socio-demographic characteristics of the students were tested using the chi square test at 5% level of significance.

RESULTS

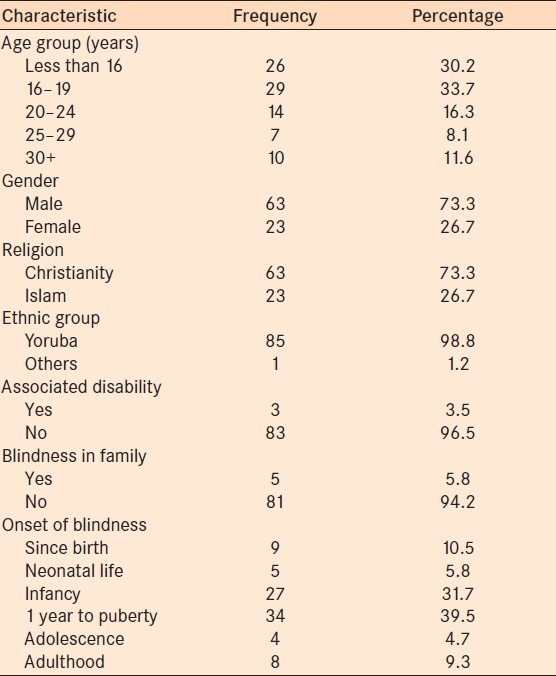

A total of 86 students were studied in the four schools for the blind in Oyo State. Two students (2.3%) were studied in Eruwa, 22 (25.6%) in Ibadan, 11 (12.8%) in Oyo Town and 51 (59.1%) in Ogbomosho. The mean age of the students was 19.4 ± 8.19 years. In all, 30% were less than 16 years of age [Table 1]. There were more males (73.3%) than females. The age–sex distribution is summarized in Figure 1. Christians constituted 73.3% of students while Muslims made up the remainder. The majority were of the Yoruba ethnic group (98.9%). None of the students declined to be examined.

Table 1.

Profile of the 86 students attending schools for the blind in Oyo State

Figure 1.

The age–sex distribution of the 86 students attending schools for the blind in Oyo State

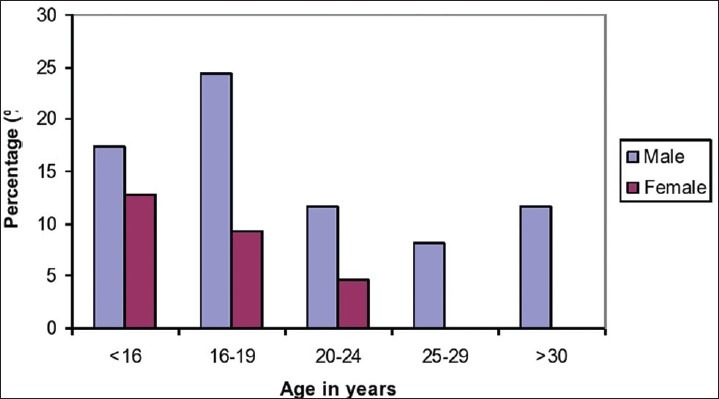

The major etiological causes of blindness were: bilateral measles keratopathy/VAD in 25 (29.1%) of the students, bilateral congenital or developmental cataracts in 23 (26.7%), bilateral optic atrophy in 12 (14%), and bilateral congenital/infantile or juvenile onset glaucoma in 11 (12.8%) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Etiology of blindness and low vision among the 86 students attending schools for the blind in Oyo State

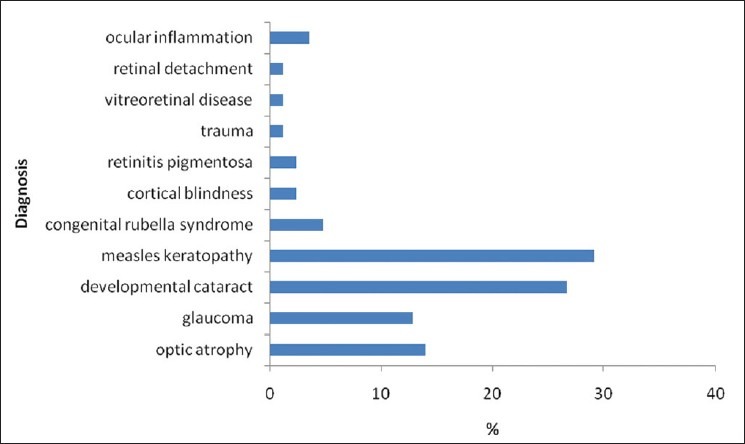

Anatomical classification showed that 21 (24.4%) of the students had bilateral phthisis bulbi, of which 16 cases were due to measles keratopathy/VAD and 5 due to congenital/developmental cataracts. Figure 3 presents the classification according to the anatomical structure involved. The cornea was the primary site in 25 students (29.1%), the lens in 23 (26.7%), the retina/optic nerve in 16 (18.6%), glaucoma in 11 (12.8%), the globe in 9 (10.5%), and cortical blindness in 2 (2.3%).

Figure 3.

Primary anatomical sites involved among the 86 students attending schools for the blind in Oyo State

Using the WHO/PBL ERCB format,5 glaucoma was diagnosed in the students by the presence of bilateral pale and totally cupped discs, and/or the presence of buphthalmos, with or without elevated intraocular pressure (IOP); congenital rubella syndrome was inferred by the presence of microphthalmia and bilateral congenital cataracts,5 and optic nerve disorders were diagnosed by the presence of bilateral optic atrophy without cupping, with or without a history of fever preceding the onset of blindness. Three students were diagnosed as being mentally retarded (using the WHO/PBL ERCB, these are students with a mental status that impedes orientation, communication, independence, personal care and establishment of relationships)5 and were thus excluded from the study.

The most common period of onset of blindness was between 1 year of age and puberty (approximately 10 years of age) in 39.5%, followed by infancy (first year of life) in 31.7% of the students. Onset of blindness in adolescence (period between the onset of puberty and onset of adulthood, essentially the teen years) was recorded in 4.7% of the students. Surgeries had been performed in the past on 9 (10.5%) of the students (before admission in the schools). Four were bilaterally pseudophakic, one was bilaterally aphakic, three had bilateral trabeculectomy, and one had a peripheral iridectomy in one eye and needling of cataract in the other eye. None of the students had undergone any surgery since enrolment in the schools for the blind. Blindness in the family was reported in 5 (5.8%) of the students.

Almost all students (97.7%) could read Braille, while 11.1% could read normal prints. Referrals to UCH, Ibadan were provided for 10 (11.6%) of the students; 9 due to bilateral congenital or developmental cataracts, and one for postuveitic cataracts. Table 2 summarizes the etiology of blindness and low vision in all the students studied in the schools for the blind in Oyo State.

Table 2.

Etiology of blindness and low vision in the 86 students studied in the schools for the blind in Oyo State

The most common cause of VI/SVI was bilateral congenital or developmental cataracts in 7 (54.4%), bilateral optic atrophy in 3 (36.4%), and retinitis pigmentosa in 1 (9.1%). The most common period of onset of VI/SVI was between 1 year and puberty in 6 (54.5%), infancy in 4 (36.4%), and adolescence in 1 (9.1%). There was 1 (9.1%) reported case of a positive family history of blindness, and 2 (18.2%) students had surgery in the past, one being bilaterally pseudophakic and the other bilaterally aphakic. All could read Braille and 8 (72.7%) could read normal prints. Distant visual aids were prescribed for 10 students (90.9%), while all 11 benefited from near visual aids. Five were referred to UCH due to bilateral congenital/developmental cataracts. None of the students were wearing spectacles or using any form of visual aids.

Distribution of visual category - prevalence of low vision/severe visual impairment and visual impairment

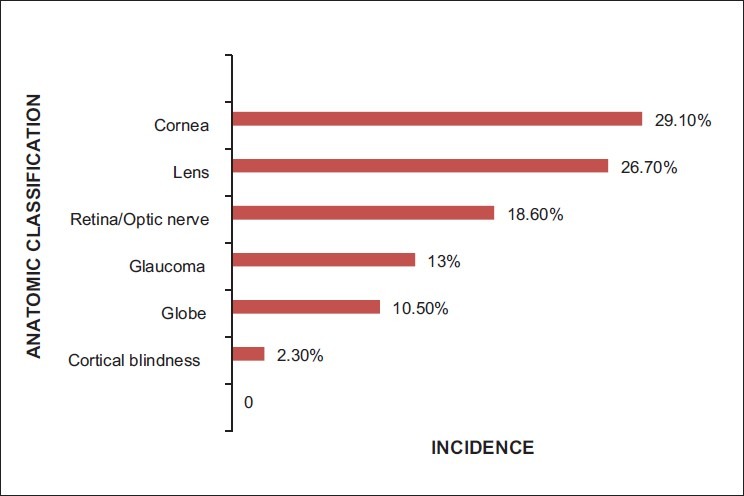

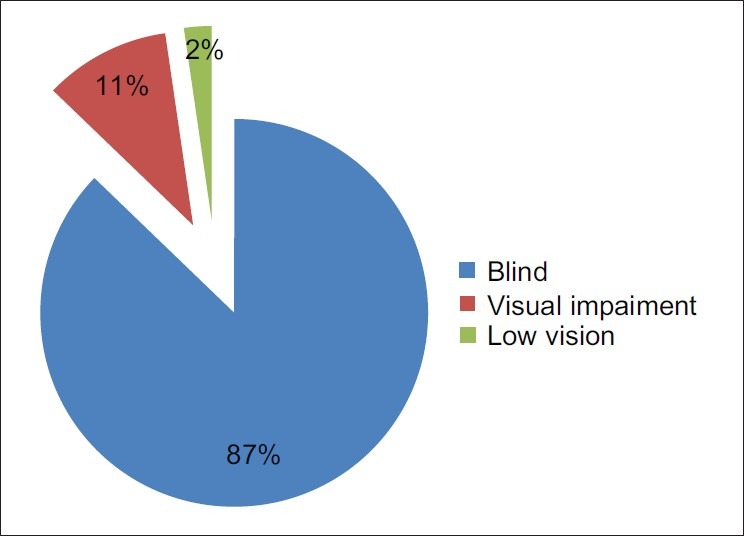

Table 3 presents the distribution of the visual categories of students before and after correction. Figure 4 shows the distribution of the visual categories of the students after correction. Most (94.2%) of the children had visual acuity in the range 3/60—no light perception (NLP) before correction but this reduced to 87.2% after correction either with refraction or with visual aids. Unaided visual acuity between 6/60 and 3/60 was found in three (3.5%) students before correction while two (2.3%) reach this range of visual acuity after correction, both coming from the category of those that were blind before correction, giving a low vision prevalence of 2.3%. A small proportion of students (2.3%) had uncorrected visual acuity between 6/18 and 6/60. The proportion in this visual acuity category improved to 10.5% after correction of some of the subjects with uncorrected visual acuity of between 6/60 and NLP, giving a proportion of visual impairment of 10.5%. None of the students was using any form of visual aids prior to the investigator's visit.

Table 3.

Visual profile of the 86 students in the schools for the blind in Oyo State

Figure 4.

Visual categories of students in the schools for the blind in Oyo State after correction

General profile of students with low vision - causes and associated characteristics

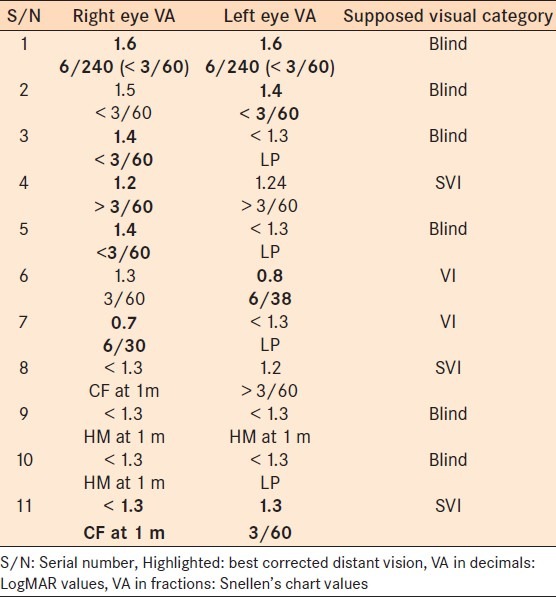

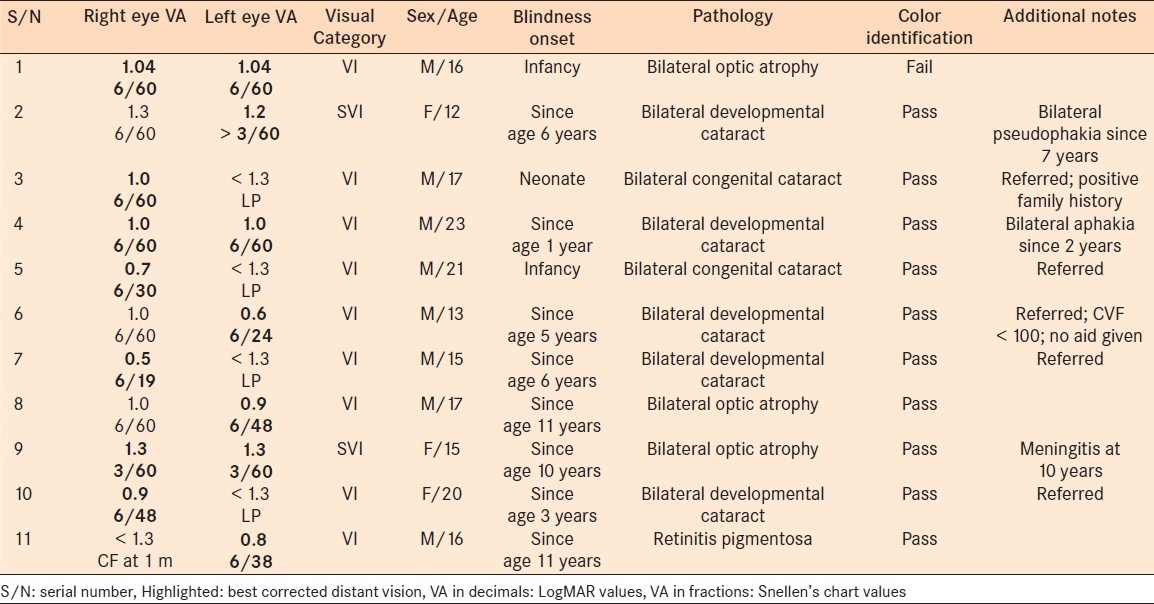

Two female students after correction had low vision, and they were aged 12 and 15 [panels 2 and 9 on Tables 4 and 5]. They could read both Braille and normal prints. Onset of blindness was at 6 and 10 years, respectively. Cause of VI/SVI was reported to be cataract and optic atrophy, respectively. The students had cataracts but were now bilaterally pseudophakic. Both were able to identify colors and read prints. Table 4 shows the uncorrected visual acuities of the 11 students that had improvement in vision with correction, and Table 5 shows the best corrected vision and other characteristics of these 11 students.

Table 4.

Uncorrected distant visual acuities (VA) in the 11 corrected students in the schools for the blind in Oyo State

Table 5.

Information about the 11 students in the schools for the blind in Oyo State with best corrected distant vision in the (severe visual impairment) SVI and (visual impairment) VI categories

General profile of students with visual impairment - causes and associated characteristics

Table 5 shows that nine students were categorized as having visual impairment, with a mean age of 17.6 years. Eight were male and one was female. All but three [panels 1, 3, and 10 of Table 5] could read normal print, however, all could read Braille. Cause of blindness was reported to be bilateral congenital/developmental cataracts in 6, bilateral optic atrophy in 2 and retinitis pigmentosa in 1 student. Onset of blindness in one was during the neonatal period, three were blind as infants, three between 1 year of age and puberty, and two during adolescence. All but one could identify colors correctly. Five of them (all with cataracts) were referred to UCH for further management. Only one did not have a distant visual aid prescribed due to a constricted visual field of < 100.

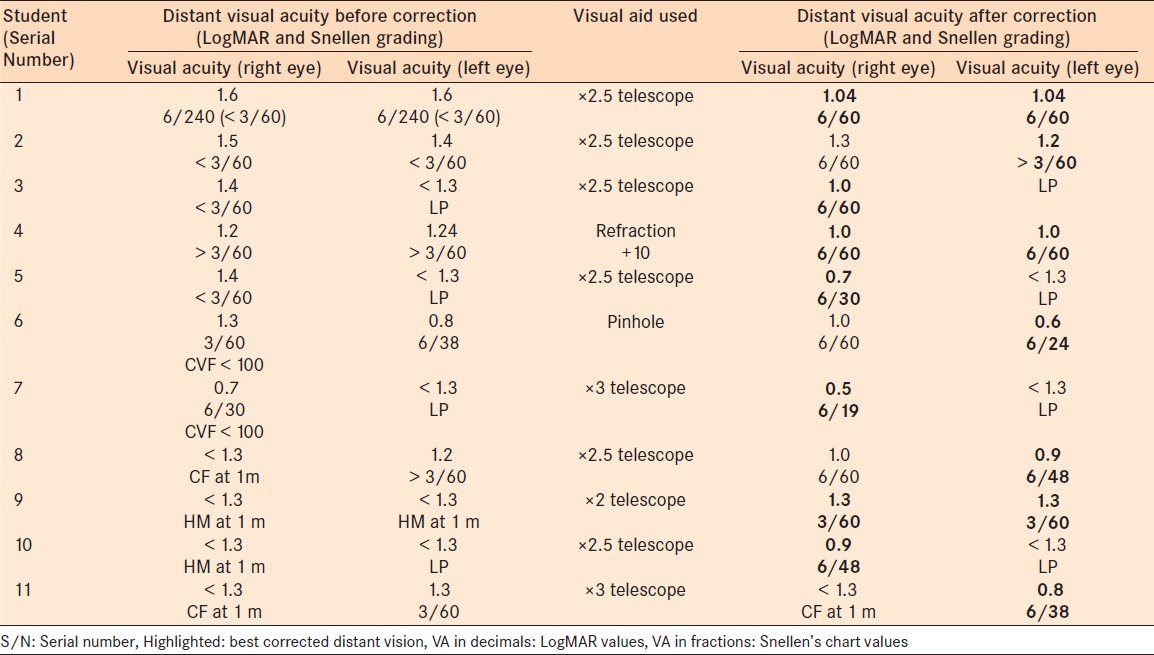

Correction of distance vision and visual aid devices prescribed

Table 6 shows the distant visual acuity (LogMAR and Snellen values) for the 11 students that had improvements in visual acuity following refraction or with the use of visual aids. The ×2.5 telescope was used in 6 of the 11 students, ×3 telescope in 2, ×2 telescope in 1, and a +10 D spherical error pair of spectacles in 1 of the students. One had his vision slightly improved with the use of a pinhole but the improvement in vision was not significant to warrant a correction; the student was, however, referred to UCH for further management.

Table 6.

Distant visual acuities (VA) before and after correction, and visual aids used for the 11 corrected students in the schools for the blind in Oyo State

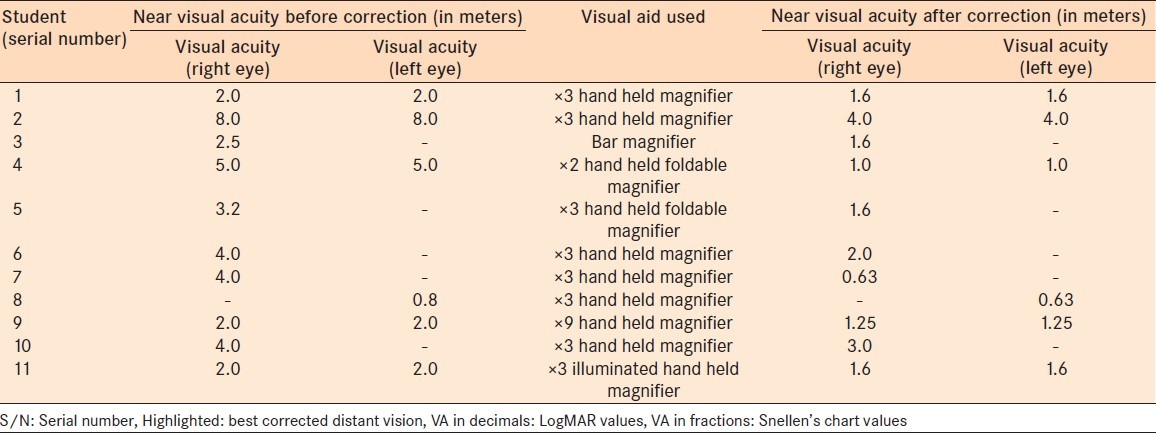

Correction of near vision and visual aid devices prescribed

Table 7 shows the near visual acuity (in meters) for the 11 students listed above. All had improved near visual acuity with the use of near visual aids. The ×3 hand held magnifier was used for 6 of the 11 students, a ×3 foldable hand held magnifier for 1, a ×3 illuminated hand held magnifier for 1, ×2 foldable hand held magnifier for 1, ×9 hand held magnifier for 1, and a bar magnifier for 1 of the students.

Table 7.

Near visual acuities before and after correction, and visual aids used for the 11 corrected students in the schools for the blind in Oyo State

DISCUSSION

This study assessed the prevalence of low vision in all four schools for the blind in Oyo State. This study, in addition to similar studies,6 went further in determining the best corrected vision and dispensing appropriate low visual aids.

In a developing country such as Nigeria, very little has been done in this field of study. In studies by Akinsola and Ajaiyeoba7,8 carried out in a school for the blind in Lagos, Nigeria, 26 children aged below 16 years who were identified as having low vision and blindness were examined to determine the causes. The authors recommend that these children be identified early, through low vision care program and those with avoidable causes treated accordingly, and also that appropriate educational facilities, optical and nonoptical devices should also be provided particularly for low vision children to enable them to achieve their optimal potential in life.7,8

Ezegwui et al.4 carried out a cross sectional study to identify the major causes of severe visual impairment/blindness (SVI/BL) among students in schools for the blind in south eastern Nigeria. In over 74% of all the students, blindness was considered avoidable.4,6

Numerous studies have been carried out in the United States. Wilkinson et al.9 and DeCarlo et al.10 showed that ongoing, comprehensive multidisciplinary low vision services are necessary to help children with visual impairments meet their educational, vocational, and other needs.9,10

Thirty percent of the students were under 16 years of age, which was relevant bearing in mind the WHO reports1–3 on childhood blindness. The high male to female ratio is similar to other studies4,7,8 carried out in developing countries and may be related to the traditional belief that education is more important for the male than for the female child. Hence, by adolescence the female students would have dropped out of school to get married or possibly start a trade. However, the age of the student, age of onset of blindness, gender, religion, ethnicity, associated disability, and family history of blindness obtained in this study were not statistically significant in the overall analysis, which compares to similar African studies.4,7,8,11

Etiologically, bilateral corneal opacities was the most common cause of blindness in the students, which correlates with results from other African studies11,12 and also in Asian studies13,14 where healthcare delivery is poor, especially in the rural and suburban regions, with a high prevalence of measles keratopathy and VAD. Where services are available they are either not accessible or unaffordable.1–3 Corneal scarring from measles keratopathy/VAD is the most common cause of childhood blindness worldwide (mainly due to the high prevalence in developing countries).1–3 Corneal scarring accounted for most cases of phthisis bulbi in this study. Poor immunization services/coverage, poor maternal and child health care, poor health education, poor nutrition, lack of clean water, poor environmental sanitation, unavailability of essential drugs, and the tendency to use traditional topical medication in treating ocular infections account for this high prevalence of corneal scarring.1–3 Blindness from cataracts was mainly from early childhood and comprised of both congenital and developmental cataracts. This was also a common cause in the African studies15–17 and was the most common cause in the south eastern Nigerian study.4 Late presentation by the parents/guardians either due to ignorance, fear, or both, and the lack of facilities and skilled personnel for managing conditions requiring surgery in developing countries contribute to the high incidence of blindness from cataracts. Low cataract surgical coverage in children with congenital/developmental cataract is also attributed to local belief that the child has to grow older before surgery can be performed, and by the time the child presents for surgery, amblyopia would have set in.1–3 Amblyopia and nystagmus were found in most of the students with treatable causes of blindness, of which cataract was a major cause. None of the students had amblyopia or nystagmus due to uncorrected refractive error. Other studies18–20 show that some success can be achieved by performing surgery or correcting amblyopia in students with low vision due to congenital/developmental cataracts and aphakia, however, success depends on the severity/density of the amblyopia and nystagmus and the time of intervention in relation to the onset of blindness.

Interestingly, apart from a Sri Lankan study,21 Asian studies rated cataract blindness lower than blindness from retinal disease. The incidence of cataract-related blindness is reducing in Asia (especially India and China) due to the rapidly improving health care services and coverage in these regions and the resultant increase in the diagnosis and treatment of these avoidable causes of blindness.3 In this study, optic atrophy, glaucoma, and retinal conditions were not as common as corneal and lens diseases, which concurs with other African studies.4,12,15,16,22 Optic atrophy diagnosed in this study was due mainly to previous episodes of meningitis or cerebral malaria. Glaucoma was classified as congenital, infantile, or juvenile, depending on the period of onset, and three children had undergone bilateral trabeculectomy. These glaucoma sufferers were not on any form of medication. The students with congenital rubella syndrome had microphthalmia and congenital bilateral cataracts; their intraocular pressures were, however, within normal limits and they had no associated macrocephaly or mental retardation.

The anatomical findings in this study correlate with the etiological findings. Corneal scarring occurred more frequently due to measles keratopathy/VAD, closely followed by lens pathologies. Corneal (preventable) and lens (treatable) pathologies account for more than half of all cases of blindness in the students examined in this study and together they are regarded as avoidable causes of blindness. Similar studies in Africa8 and Asia23–25 also used the same classification with the magnitude of the problem being mainly in these regions.12,18,26,27

Onset of blindness in this study was mainly between the first year of life and puberty and this was a result of the high incidence of corneal lesions commonly found during this period due to measles/VAD from poor immunization services/coverage, inadequate child health care, poor nutrition, lack of clean water, poor environmental sanitation, and the use traditional eye medication to treat ocular infections.1,2

Surgery had been performed on some of the students before admission into the schools for the blind. In the current study, the aphakia improved with refraction and also benefited from near vision aid. One of the pseudophakics had improved vision with both distance and near visual aids, comparable to a study from Thailand.28 It was difficult to tell if the students who had surgery came from more educated families or if their families had a higher social status. Most of the students were referred to the base hospital (UCH, Ibadan) for congenital/developmental cataracts and half of these have useful corrected vision. None of the students had undergone surgery since admission into the schools.

All the students studied in Braille in accordance with their curriculum and irrespective of their visual acuities and ability to read print. The schools in Ibadan and Ogbomosho have been partially incorporated into regular schools, which should aid educational, vocational, and social development as noted in similar studies.4,9,10,29,30 Eleven of the students could read print which they learnt before losing their sight. As with similar studies,31 students with mental retardation were excluded from the study.32

The most common pathology associated with the students who had vision improvement with visual aids and refraction was cataracts, which compares with other studies,4,9,22,27,33 and most of them were referred to the base hospital for management. The response to the base hospital referral was, however, poor despite the optimism of the teachers and students; this was due to the reluctance of the parents (despite being assured of a 50% discount of the surgery bill). Seventy three percent of this small group of students lost vision before puberty. Two thirds of these students with improved vision could read print and most of them had good color perception. Nine of these students were corrected with telescopes for distant vision and one (aphakic) had +10 DS aphakic spectacle correction. All of them had magnifiers for correction of near vision, and 4 of the 11 were under 16 years of age. All the telescopes and magnifiers were provided for the students by the investigator at no cost to the students. Numerous studies9,12,13,17,18,20,22,25,29,30,33–37 have shown that a significant number of students in schools for the blind benefit from visual aids.

The students were followed up monthly for 6 months to assess the impact of the low vision devices on their academic performance and daily activities. They all found the devices very helpful in studying in school and carrying out tasks at home. The beneficiaries of telescopes claimed it took some time for them to get accustomed to the magnification provided by the devices.

Some limitations were encountered in this study including poor history by some students and parents/guardians of the precise period of onset, cause, and process of blindness; this made correlation of findings and determining the exact diagnosis difficult. Also, further evaluation was hampered by unavailability of electrophysiological devices and a portable ocular ultrasound device.

A surprising and significant finding was that 9 (82%) of the 11 students corrected fell within the visual impairment category, while the remaining were corrected to the low vision category. This study shows that the prevalence of low vision in the schools for the blind in Oyo State is 2.3%, which is similar to the eastern Nigerian4 and an Indian study.25 Additionally, the prevalence of visual impairment was higher at 10.5%. This shows that more studies and visual assessment need to be carried out on students in blind schools to determine which students can benefit from distance and near visual aids.

Footnotes

Source of Support: None

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Global initiative for the elimination of avoidable blindness. Geneva: WHO; 1998. WHO; pp. 1–2. (WHO/PBL/9761) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Preventing blindness in children: Report of a WHO/IAPB scientific meeting. Geneva: WHO; 2000. WHO; p. 1. (WHO/PBL/0077) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert C, Foster A. Childhood blindness in the context of VISION 2020 - The Right to Sight. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:227–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ezegwui IR, Umeh RE. Causes of childhood blindness: Result from schools of the blind in South Eastern Nigeria. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:20–3. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO/PBL Eye Examination Record for Children with Blindness and Low Vision (ERCB) Coding instructions and manual for data entry in EPI-INFO. [Last accessed in 2007 Aug]. Available from: http://www.who.int/ncd/vision2020_actionplan/documents/CodingInstructions2.pdf .

- 6.Gilbert C, Anderton L, Dandona L. Prevalence of blindness and visual impairment in children- a review of available data. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1999;6:73–81. doi: 10.1076/opep.6.1.73.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akinsola FB, Ajaiyeoba AI. Causes of low vision and blindness in children in a blind school in Lagos Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2002;21:63–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akinsola FB, Ajaiyeoba AI. Assessment of educational services available to blind and low vision school children in Lagos, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2002;21:37–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilkinson ME, Stewart IW. Iowa's pediatric low vision services. J Am Optom Assoc. 1996;67:397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeCarlo DK, Nowakowski R. Causes of visual impairment among students at the Alabama School for the Blind. J Am Optom Assoc. 1999;70:647–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silver J, Gilbert CE, Spoerer E, Foster A. Low vision in East African blind schools: Need for optical low vision devices. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:814–20. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.9.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kello AB, Gilbert C. Causes of severe visual impairment and blindness in children in schools for the blind in Ethiopia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:526–30. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.5.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalikivayi V, Naduvilath TJ, Bansal AK, Dandona L. Visual impairment in school children in Southern India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1997;45:129–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sitorus RS, Abidin MS, Prihartono J. Causes and temporal trends of childhood blindness in Indonesia: Study at schools for the blind in Java. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1109–13. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.110445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster A. Medical report to the Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. 1986 (Unpublished report) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert CE, Wood M, Waddel K, Foster A. Causes of childhood blindness in east Africa: Results in 491 pupils attending 17 schools for the blind in Malawi, Kenya and Uganda. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1995;2:77–84. doi: 10.3109/09286589509057086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waddell KM. Childhood blindness and low vision in Uganda. Eye (Lond) 1998;12(Pt 2):184–92. doi: 10.1038/eye.1998.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gothwal V, Herse P. Characteristics of a low vision population in a private eye hospital in India. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2000;20:212–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng Y, Sun B, Cui T. Use of visual aids for vision of disabled children. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 1999;35:459–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gogate P, Deshpande M, Sudrik S, Taras S, Kishore H, Gilbert C. Changing pattern of childhood blindness in Maharashtra, India. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:8–12. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.094433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilbert C, Foster A. Causes of blindness in children attending four schools for the blind in Thailand and the Philippines. A comparison between urban and rural blind school populations. Int Ophthalmol. 1993;17:229–34. doi: 10.1007/BF01007745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan DS, Lai TY, Cheung EY, Lam DS. Causes of childhood blindness in a school for the visually impaired in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2005;11:85–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirdehghan SA, Dehghan MH, Mohammadpour M, Heidari K, Khosravi M. Causes of severe visual impairment and blindness in schools for visually handicapped children in Iran. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:612–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.050799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi Y, Xu Z. An investigation on causes of blindness of children in seven blind schools in East China. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2002;38:747–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hornby SJ, Adolph S, Gothwal VK, Gilbert CE, Dandona L, Foster A. Requirements for optical services in children with microphthalmos, coloboma and microcornea in southern India. Eye (Lond) 2000;14(Pt 2):219–24. doi: 10.1038/eye.2000.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kocura I, Kuchynkaa P, Rodnýa S, Barákováa D, Schwartzb EC. Causes of severe visual impairment and blindness in children attending schools of the visually handicapped in the Czech Republic. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:1149–52. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.10.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sloan LL. Reading aids for the partially sighted: Factors which determine success or failure. Arch Ophthalmol. 1968;80:35–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1968.00980050037005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prabriputaloong A, Yospaiboon Y, Kittiponghansa S, Viwathanatepa M, Sangveejit J. Causes of blindness and restoration of sight for the students in Schools for the Blind, Khon Kaen. J Med Assoc Thai. 1989;72:606–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Honby SJ, Adolf S, Gothwal VK, Gilbert CE, Dandona L, Foster A. Evaluation of children in six blind schools in Andhra Pradesh. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2000;48:195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pal N, Titiyal JS, Tandon R, Vajpayee RB, Gupta S, Murthy GV. Need for optical and low vision services for children in schools for the blind in North India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2006;54:189–93. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.27071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu B, Huang W, He M, Zheng Y. An investigation on the cause of blindness and low vision of students in blind school in Guangzhou. Yan Ke Xue Bao. 2007;23:117–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Dijk K. Providing care for children with low vision. Community Eye Health. 2007;20:24–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hornby SJ, Xiao Y, Gilbert CE, Foster A, Wang X, Liang X, et al. Causes of childhood blindness in the Peoples Republic of China: Result from 1131 blind school students in 18 provinces. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:929–32. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.8.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ingelse J, Steele G. Characteristics of the pediatric/adolescent low-vision population at the Illinois School for the Visually Impaired. Optometry. 2001;72:761–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silver J, Gould E. A study of some factors concerned in the schooling of visually handicapped children. Child Care Health Dev. 1976;2:145–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.1976.tb00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faye EE, Padula WV, Padula JB. Clinical low vision. 2nd ed. Boston, USA: 1984. The low vision child; pp. 437–75. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leat S, Rumney NJ. Use and non-use of low vision aids by visually impaired children. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1991;11:10–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]