Abstract

Background:

The purpose of the study was to evaluate the oral and dental findings of uremic patients receiving hemodialysis and to compare the Results between diabetic and non-diabetic groups.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 100 patients undergoing hemodialysis were classified into diabetic and non-diabetic groups and examined for uremic oral manifestations, dental caries (DMFT), and periodontal status (CPITN). Mann-Whitney test of significance has been applied for analyzing DMFT score and chi-square test is used for analyzing CPITN score.

Results:

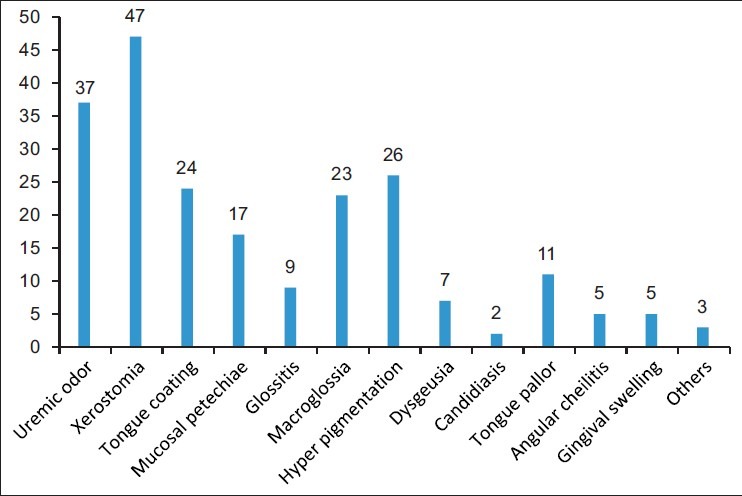

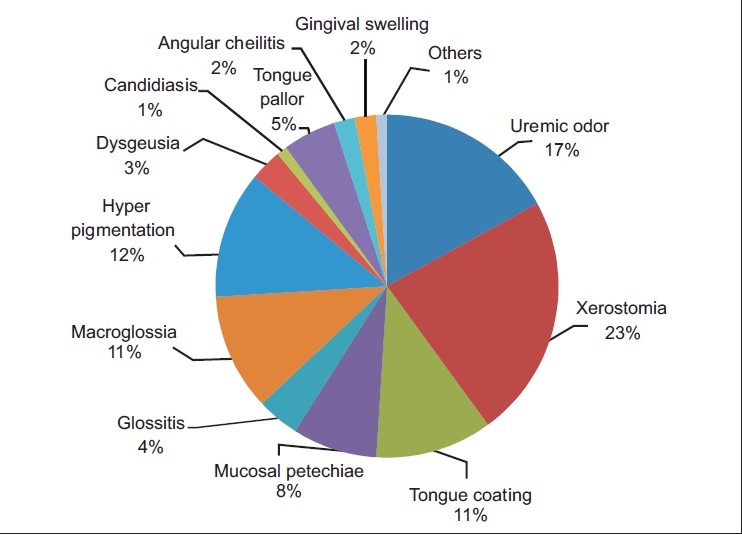

Of the study group, 46% were diabetic and only 11% of them did not have any oral manifestation. Oral manifestations observed were xerostomia and uremic odor, which contributed to 47 (23%) and 37 (17%), respectively. Hyperpigmentation was present in 26 (12%), macroglossia in 23 (11%), and uremic tongue coating in 24 (11%). Mucosal petechiae were seen in 17 patients contributing to 8% of total patients. Eleven patients had tongue pallor (5%), 9 patients had glossitis with depapillation (4%), and 7 patients had dysgeusia (3%). Angular cheilitis and gingival swelling were seen in 5 patients (2%).

Conclusion:

The oral and dental manifestations were higher in prevalence in the study group. However, there was no significant difference between the two groups.

Keywords: Diabetic nephropathy, hemodialysis, hyperpigmentation, uremic coating

INTRODUCTION

The increasing prevalence of type II diabetes in industrialized countries can be seen as an increase in the number of patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). The number of patients with renal disease undergoing dialysis treatment and kidney transplant patients is increasing and, consequently, more such patients are also seen in the dental office. The progressive loss of renal function Results in an array of biochemical and clinical manifestations. These include aggravation of hypertension, retention of nitrogenous waste products, anemia due to erythropoietin deficiency, tendency to acidosis, and disturbed calcium-phosphorous-vitamin D metabolism that often leads to excessive secretion of the parathyroid hormone. Patients with chronic renal failure and patients with kidney transplants have an increased risk of oral diseases and symptoms that show in the mouth. Chronic renal failure is characterized by progressive loss of nephrons and simultaneous progressive loss of renal function. The disease goes through five stages: a preclinical stage and four clinical stages of progressive renal failure, from mild to moderate to severe and ultimately ends in uremia. As the biochemical environment deteriorates with decreasing glomerular filtration rate, changes inevitably occur in a variety of organ systems. In the mild stage, the excretory and regulatory functions of the kidney are minimally affected. The moderate stage is represented by mild azotemia, inability to concentrate urine, and mild anemia. In the severe stage, the anemia becomes advanced and is accompanied by metabolic acidosis, disturbances in sodium levels, and edema. In the uremic stage, the cardiovascular, neuromuscular, and hematopoietic systems are affected. Osseous abnormalities and endocrine imbalances also occur. Chronic renal failure is often complicated by multiple infections. This increased susceptibility to infection is due to impairments in both specific and non-specific host defenses.[1] The aim of the study is to examine the dental and oral manifestations in diabetic and non-diabetic uremic patients undergoing hemodialysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this study, a total of 100 ESRD patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis were examined. The patients were divided into diabetic and non-diabetic groups according to their medical history. A detailed case history was taken for all the patients, which included general examination and intra-oral and extra-oral examination; and blood investigation reports of hemoglobin, packed cell volume (PCV) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine were also noted.

Following this, the patients were examined for objective, known and described manifestations including uremic odor, uremic coating, mucosal petechiae or ecchymosis, macroglossia, xerostomia, enamel hypocalcification and other findings.

Objective findings were recorded as presence or absence of the manifestations and were photographed. Radiographs of patients with a history of renal osteodystrophy were taken to observe any changes in the jaw bone and analyzed. Assessment of the dental health consisted of 2 parts: DMFT index for the incidence of dental caries and the community periodontal index (CPI) for appraising need for periodontal treatment. Both dental examinations were performed with a WHO probe and mouth mirror. For the examination of DMFT index, the sum of decayed (D), missing (M), and filled (F) teeth was obtained. Review of the patients was done periodically to observe the persistence of oral lesions. According to World Health Organization (WHO) protocol, the dentition was divided into sextants, and the following CPI was used.

Code 0: Healthy periodontium without pathologic changes.

Code 1: Bleeding on gentle probing.

Code 2: Calculus deposition.

Code 3: Probing depth of 4 to 5 mm.

Code 4: Probing depth 6 mm or deeper.

Code x: 3 or more missing teeth.

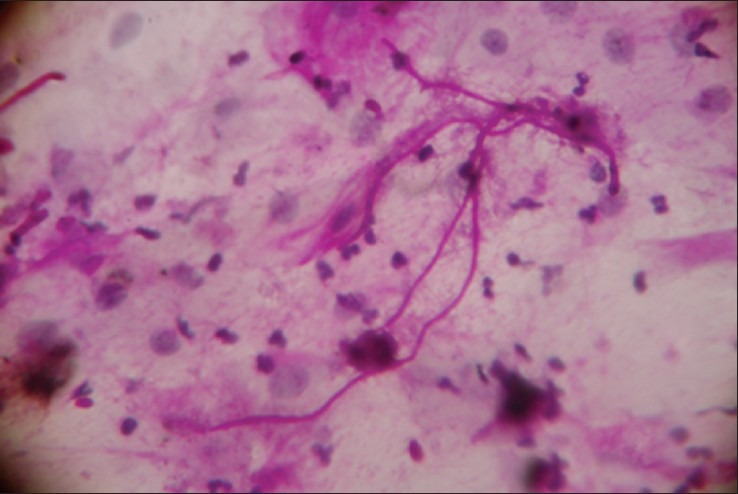

The highest code in the sextant was recorded to identify the periodontal condition. Exfoliative cytology was done for patients who were suspected for oral candidiasis. The smears after fixation in absolute alcohol were stained by periodic acid schiff (PAS) reagent for demonstration of the fungi.

RESULTS

The study group included a total of 100 patients out of which 62% were males and 38% were females.

The age range of patients varied from 25 to 79 years. Between the range of 25 and 35 years, males and females are equal, whereas males predominate between 35 and 75 group. No females were present beyond 75 years of age. In this study, 46% were diabetic and 64% were non-diabetic. The prevalence of oral manifestations among them was 89% and so 11% of them did not have any oral manifestation.

The BUN level in the study group ranged from 100 to 134 mg/ dL with mean ± SD (Standard Deviation) of 109.76±7.928 without a considerable amount of wide deviation away from the normal width of the normal curve.

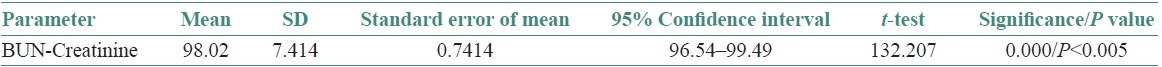

The creatinine level in the study group ranged from 2 to 20 mg/dL with mean ± SD of 11.74±7.3.42486 with minimal amount of less negative skewness, and comparison between the two parameters by Student t test is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of bun and creatinine levels

As the BUN level increases, there is also rise in creatinine level and the difference is statistically significant were P<0.005.

Oral manifestations observed were xerostomia and uremic odor, which contributed to 47 (23%) and 37 (17%), respectively. Hyperpigmentation [Figure 1] was present in 26 individuals (12%), macroglossia [Figure 2] in 23 individuals (11%), and uremic tongue coating [Figure 3] in 24 individuals (11%). Mucosal petechiae [Figure 4] were seen in 17 patients contributing to 8% of total patients. Eleven patients had tongue pallor (5%), 9 patients had glossitis with depapillation [Figure 5] (4%), and 7 patients had dysgeusia (3%). Angular cheilitis and gingival swelling were seen in 5 patients (2%). Candidiasis [Figures 6 and 7] was seen in 2 patients (1%). “Other diseases” included 1 patient having denture stomatitis, enamel hypoplasia, and fissured tongue each [Figures 8 and 9].

Figure 1.

Hyperpigmentation

Figure 2.

Macroglossia with crenations in the lateral border

Figure 3.

Uremic tongue coating

Figure 4.

Mucosal petechiae

Figure 5.

Glossitis with depapillation of tongue

Figure 6.

Candidiasis

Figure 7.

Smear showing candidal hyphae along with mixed inflammatory cells (PAS stain, 40 × magnification)

Figure 8.

Bar diagram showing distribution of the various oral manifestations

Figure 9.

Pie chart showing percentage of distribution of the various oral manifestations

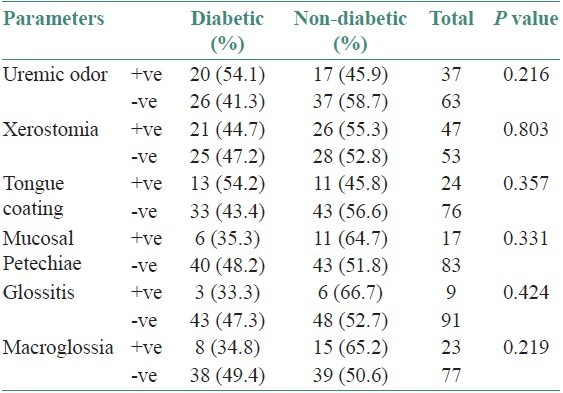

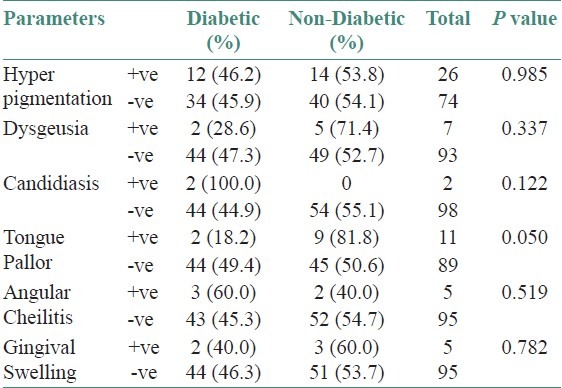

On analyzing the data of this study in relationship to oral manifestations among uremic patients who have been categorized into diabetic and non-diabetic individuals, it has been observed that patients who are having uremic odor, xerostomia, tongue coating, mucosal petechiae, glossitis, macroglossia, hyperpigmentation, dysgeusia, candidiasis, angular cheilitis, and gingival swelling did not have significant difference.

Tongue pallor was the only manifestation where P value <0.05 showing significant difference among diabetic and non-diabetic uremic patients [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 2.

Oral and dental manifestations of diabetic and non-diabetic patients

Table 3.

Oral and dental manifestations in diabetic and non- diabetic patients

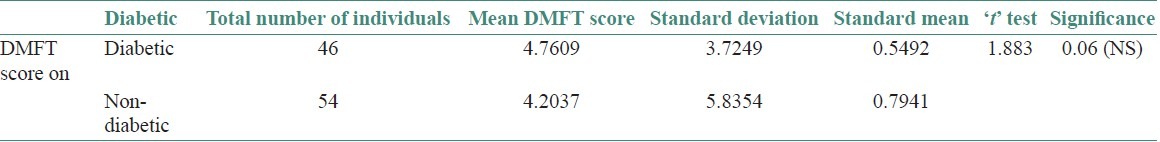

Among diabetic and non-diabetic individuals who had DMFT score, it was observed that a total of 46 diabetics had increase in DMFT score and comparatively 54 non-diabetics had significant DMFT score. The mean DMFT score was 4.7607 in diabetics and 4.2037 in non-diabetics. Hence, Mann-Whitney test of significance was applied and P was > 0.05 and there was no significant difference observed between the two groups [Table 4].

Table 4.

Analysis of DMFT score using Mann- Whitney test

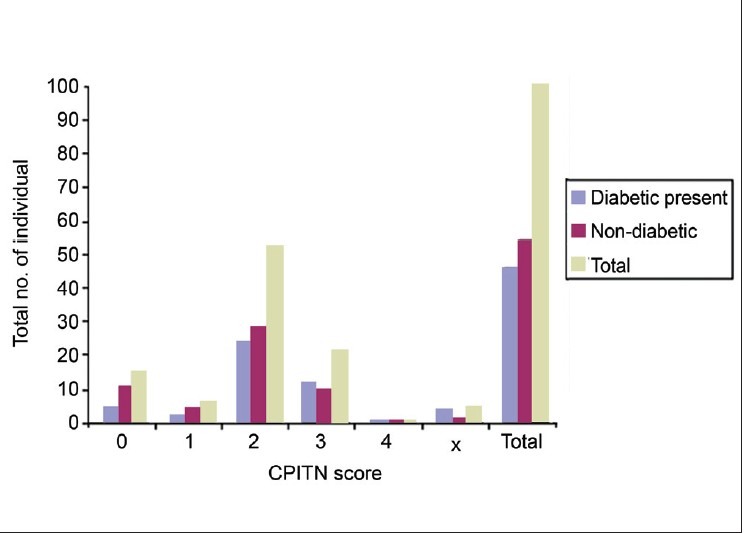

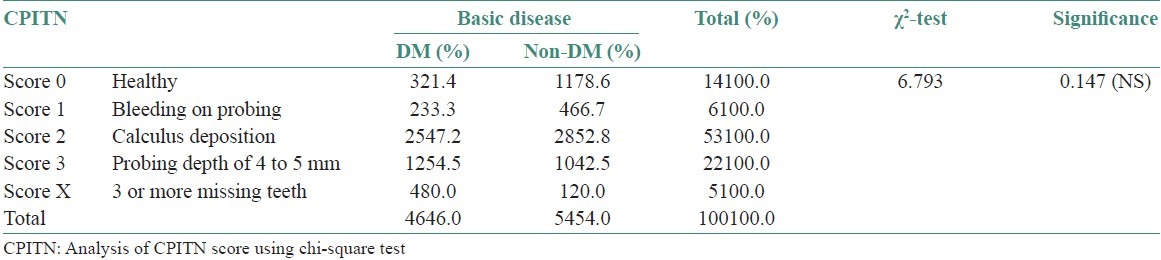

The highest CPITN code was taken from diabetic and non-diabetic uremic patients. Code 0; Code 1, and Code 2 were more in the non-diabetic group whereas Code 3 and Code x were more in the diabetic group. Code 4 was not observed in both the groups. Chi-square test was used to analyze the various CPITN codes among diabetic and non-diabetic uremic patients where P > 0.05. Thus, no significant difference was observed between the two groups [Figure 10, Table 5].

Figure 10.

Comparison of CPITN scores in diabetic and non-diabetic uremic patients

Table 5.

Analysis of CPITN score using chi-square test

DISCUSSION

Chronic renal failure (CRF) progressively and irreversibly leads to uremia. Uremic patient must receive dialysis or renal transplantation to maintain their normal body homeostasis. As renal function deteriorates, patients with CRF may suffer a number of medical problems in the metabolic-endocrine, hematologic-immunologic, dermatologic, cardiovascular, neuromuscular, and gastrointestinal systems. Uremic syndrome from kidney failure also includes changes in the oral cavity. In the present study, there was a higher predilection of males (62%) when compared with females (38%). The study group had an age range of 25–79 years. The peak age range was between 45 and 65 years. The study group comprised 54% non-diabetics and 46% diabetics. In the study, all patients were on hemodialysis, so when the linearity difference was compared, the curve projected an increase in order of occurrence and it clearly showed that all patients had a severe degree of uremic dysfunction. Out of 100 patients, 89 patients had oral manifestations and 11 patients did not have any oral manifestations. The oral manifestations included xerostomia, uremic odor, hyperpigmentation, macroglossia, tongue coating, tongue pallor and mucosal petechiae commonly whereas dysgeusia, angular cheilitis, gingival swelling, glossitis, and candidiasis were observed less commonly. There was one patient each with fissured tongue, enamel hypoplasia and denture stomatitis. Features like xerostomia, dysgeusia, and uremic tongue correlated with the study by Chuang et al.[2] A combination of direct uremic involvement of the salivary glands, chemical inflammation, and dehydration from restricted fluid intake leads to decreased salivary flow. Kellet[3] has also reported 4 cases with non-ulcerative uremic stomatitis in different parts of the oral mucosa. In this study, uremic coating was found only in the dorsal aspect of tongue; however, they were also non-ulcerative. Although its exact cause is uncertain, uremic stomatitis can be regarded as a chemical burn or as a general loss of tissue resistance and inability to withstand normal or traumatic influences.[4] Gingival or crevicular fluid contains urea at a higher concentration than plasma or mixed saliva.[3] In the study done by Kho et al.,[5] 34.1% patients had uremic odor, 32.9% had xerostomia, 31.7% had taste change, and 12.2% had tongue/mucosa pain. Mucosal petechiae and tongue coating were seen in 12.2% of patients. In addition, enamel hypoplasia and oral ulcers were found in 3.7% and 1.2% patients, respectively. All the features present in this study were also present in our group of patients except for the feature that only one patient exhibited enamel hypoplasia. The rarity of this dental defect may reflect a late onset of renal disease that occurred after the maturation of dentition in these patients, because enamel hypoplasia according to Davidovich and Koch et al.[6] is evident in the deciduous dentition, indicating the possibility of a congenital disease. The mucosal petechiae/ecchymosis is associated with the anticoagulants in hemodialysis sessions.[2] The severity of hypoplasia correlates with age and the duration of ESRD and dialysis suggesting that CRF may influence dental morphogenesis. Hyperpigmentation is the third most common feature observed in this study but none has been reported so far. However, it is one of the dermatologic manifestation of the uremic syndrome.[4] Angular cheilitis has been described in up to 4% of renal allograft recipients.[7,8] Other symptoms include taste change and macroglossia, which is more likely related to anemia and retained uremic toxins. Abnormal taste perception has also been attributed to zinc deficiency or part of the general neurological disturbance of CRF.[9] Uremic odor is caused by a high concentration of urea in the saliva; the urea is broken to ammonia.[4,5] Lorato[10] reported that the accumulation of ammonia might irritate the oral mucosa resulting in glossitis and stomatitis, and that oral mucosal change might be only a phase of generalized mucosal breakdown. Candidiasis was positive in two patients, both of whom were diabetic. Candida infection is being regarded as characteristic of CRF,[8] with incidence as high as 37%; here the influence of diabetes mellitus could also be a contributing factor.[11] Gingival enlargement secondary to drug therapy is the most reported oral manifestation of renal disease.[8] However, in this study a total of five patients were reported to have gingival swelling. In this study, there was no significant difference in the DMFT index and CPITN index between the diabetic and non diabetics. According to Scott De Rossi and Michael Glick,[12] the low caries rate in spite of xerostomia is attributed to the inhibition of plaque and bacteria by high levels of salivary urea. The finding might be explained by the fact that high amount of urea in the saliva can lead to an increase in its buffering ability as a result of high concentration of ammonia arising from urea hydrolyzation.[4,2] The CPITN scores revealed that code 0, code 1, and code 2 were more in the non-diabetic group whereas code 3 and code x were more in the diabetic group. Code 3 indicates pocket depth of 4 to 5 mm and code x indicates 3 or more missing teeth, indicating diabetics have increase in missing teeth and peridontitis compared with non-diabetics. Although biological difference was seen, statistical analysis showed no significance.

CONCLUSION

The oral and dental manifestations appear to be higher in prevalence in the study group. There was no significant difference between the diabetic and non-diabetic groups. Further research is needed to clarify the combined influence of diabetic nephropathy on oral health.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Khocht A. Periodontitis associated with chronic renal failure: A case report. J Periodontal. 1996;67:1206–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.11.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chuang SF, Sung JM, Kuo SC, Huang JJ, Lee SY. Oral and dental manifestations in diabetic and non diabetic uremic patients receiving hemodialysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radio Endod. 2005;99:689–95. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.06.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kellet M. Oral white plaques in uremic patients Br. Dent J. 1983;154:366–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4805094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenberg G. 10th ed. Hamilton, Ontario: BCDeckerInc; 2003. Burkett's oral medicine, diagnosis and treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kho HS, Lee SW, Chung SC, Kim YK. Oral manifestations and salivary flow rate, ph, and buffer capacity in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis. Oral Surg Oral med Oral Pathol Radiol Endod. 1999;88:316–9. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidovich E, Schwartz Z, Davidovitah M, Eidelmon E, Binstein E. Oral findings and periodontal status in children, adolescents and young adults suffering from renal failure. J Clin Periodontal. 2005;32:1076–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klassen JT, Krasko BM. The dental health status of dialysis patients. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:34–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Proctor R, Kumar N, Stein A, Moles D, Porter S. Oral and dental aspects of chronic renal failure. J Dent Res. 2005;84:199–208. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burge JC, Schemmel RA, Park HS, Green JA. Taste acuity and zinc status in chronic renal disease. J Am Diet Assoc. 1984;84:1203–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larato DC. Uremic stomatitis: Report of a case. J Periodontal. 1975;46:731–3. doi: 10.1902/jop.1975.46.12.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guggenheimer J, Moore PA, Rossie K, Myers D, Mongelluzzo MB, Block HM, et al. Insulin-dependant diabetes mellitus and oral soft tissue pathologies. I prevalence and characteristics of non-candidal lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Radiol Endo. 2000;89:563–9. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.104476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Rossi SS, Glick M. Dental considerations for the patient with renal disease receiving hemodialysis. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:211–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]