Abstract

Sensitive skin syndrome (SSS) is a common and challenging condition, yet little is known about its underlying pathophysiology. Patients with SSS often present with subjective complaints of severe facial irritation, burning, and/or stinging after application of cosmetic products. These complaints are out of proportion to the objective clinical findings. Defined as a self-diagnosed condition lacking any specific objective findings, SSS is by definition difficult to quantify and, therefore, the scientific community has yet to identify an acceptable objective screening test. In this overview we review recent epidemiological studies, present current thinking on the pathophysiology leading to SSS, discuss the challenges SSS presents, and recommend a commonsense approach to management.

Keywords: Cosmetic intolerance syndrome, sensitive skin syndrome, status cosmeticus

Introduction

What was known?

Sensitive skin syndrome is a common and challenging condition, yet little is known about its underlying pathophysiology.

Sensitive skin is a common term used by patients and clinicians, as well as the cosmetic industry, and represents a complex clinical challenge faced by dermatologists and other skin care professionals. Patients with sensitive skin often present with subjective complaints that are out of proportion to the objective clinical findings. The patients complain of severe facial irritation, burning, and/or stinging after application of cosmetic products and toiletries such as sunscreens and soaps, yet they do not demonstrate the clinical stigmata of scaling, induration, and/or erythema that would be expected in known inflammatory or allergic processes.[1,2] The condition is often worsened by specific climatic conditions and may affect areas other than the face.[3,4] Maibach described the cosmetic intolerance syndrome (CIS), which probably covers the bulk of the clinical presentation of the sensitive skin syndrome (SSS).[1] Fisher is credited with coining the term status cosmeticus to describe one extreme of the natural history of the CIS in which the patient gradually becomes completely intolerant to the application of any cosmetic product.[5] Fundamentally, SSS is a state of hyperreactivity to environmental stimuli, presenting with a clear clinical picture and resulting from a single underlying pathology or a combination of pathologies.[3]

The Sensitive Skin Syndrome - Catch 22

Defined as a self-diagnosed condition, SSS is by definition difficult to quantify. Some of the contradictions between investigators could be explained by flawed methodologies since the scientific community has yet to identify an acceptable objective screening test for sensitive skin.[6] However, it is not only the subjective nature of the complaints that make SSS difficult to diagnose. Robinson, by performing patch testing with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and looking for intra-individual response patterns, found that there is significant positive correlation between SDS and other irritants but noted overall low correlation coefficients. He therefore deduced that it is inappropriate to define a subject's reaction to a chemical based on his or her response to another irritant.[7] Marriott reinforced this idea by testing the same fundamental problem. She skin-tested 58 subjects with history of strong positive SDS or lactic acid response. The subjects were tested with irritants and a sensory perception assessment was performed. The investigators showed that even in this ‘SDS- or lactic acid-positive’ group, a reaction to one irritant could not predict a reaction with another.[8] To further complicate matters there is evidence to suggest that no correlation exists between the lactic acid stinging test and the response to SDS.[9] This data resonate the idea that even the reference irritants commonly used in studies of this topic do not correlate with each other and with hyperreactivity tendencies. Finally, Judge tested 22 nonatopic adults with varying doses of SDS and found marked inter-individual variation in the response threshold.[10] These findings point to the complex nature of SSS. Applied clinically, this complexityreinforces the need for a thorough diagnostic algorithm and, specifically, the need to test patients with multiple, repeated and complete (i.e. all cosmetics applied by the patient at home) patch testing before making a diagnosis.

Epidemiological Data

In order to formulate a systematic clinical approach, the medical and cosmetic communities have attempted to characterize the condition. Lacking an objective screening test, investigators resorted to epidemiological studies using patient surveys. In a large epidemiological study in the UK (n = 2316), a staggering 51.4% of women and 38.2% of men self-reported themselves as having sensitive skin.[11] Of note, race and age were not reported in this study. Interestingly, atopy did not appear to predict self-perceived sensitivity in the participating women. In addition, in the same study self-reports of SSS symptoms were statistically over-represented in the ‘self-reported sensitive’ cohort compared to the ‘self-reported nonsensitive’ cohort. This finding validates the link between self-perception of sensitive skin and neurosensory discomfort. This link has been validated in previous studies.[12] Two recent studies in the US and Europe made similar observations. In the US, the overall prevalence of sensitive skin was 44.6%. Females were significantly more concerned about sensitive skin than men; however, no age or ethnic differences were found.[13] The European study reported an overall sensitive skin prevalence of 38.4% and found no ethnic differences.[14] The European study, once again, demonstrated that people who reported having sensitive skin were significantly more likely to experience SSS symptoms. Of note, both the American and European studies used large samples (n = 994 and n = 4506, respectively); however, they were both limited by a phone survey methodology and the lack of any objective assessment.

In light of the increased incidence of self-reported hypersensitivity in females, Robinson's effort to objectively determine hyperreactivity draws interesting conclusions. He compared the patch test responses of 384 patients to SDS as the positive control and found increased reactivity in males compared to females.[15] Lammintausta tested seven males and seven females with sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) and then performed visual inspections, transepidermal water loss measurements, and dielectric water content measurements but like other investigators found no reactivity differences between males and females,[16,17] adding to the overall controversy. Female self-perception of sensitivity is consistently increased compared to that of males, yet when put through objective reactivity testing the trend is unclear.

This epidemiologic controversy also appears to pertain to ethnic tendencies towards hyperreactivity. Ethnic differences in skin reactivity have been explored through the years, leading to the clinical hypothesis that black skin is less reactive than Caucasian skin, which is in turn less reactive than Asian skin.[18] However, an epidemiological telephone survey performed in the US (n = 811) revealed similar incidence of self-reported sensitive skin across four major ethnic groups (Afro-Americans, Asians, Euro- American, and Hispanics). The incidence rate of 52% is comparable to the incidence found in the UK (see above). The investigators did, however, find minimally statistically significant ethnic differences in the self-reported triggers and symptoms of sensitivity: Afro-Americans reacted less to environmental and alcoholic triggers; Hispanics reacted less to alcohol; Asians reacted more to wind, spices, and alcohol; and Euro-American reacted more to wind. In terms of symptomology, statistically significant increase in recurrent itching on the face was noted in the Asian population, and fewer Euro-American avoided certain cosmetics due to skin reactivity.[19] These findings were supported in a critical literature review, which showed that the evidence supporting the ethnic difference hypothesis using objective tests rarely reaches statistical significance and is often biased by subjective endpoints.[18,20]

Recent data looking into age-related differences in hyperreactivity are showing more consistent results. Whorl performed patch testing with 34 irritants on 2776 patients and found that young patients were more reactive than old patients.[21] Robinson's findings also corroboratedthe trend towards increased reactivity in the young subjects compared to the old subjects.[15]

Current Thinking on Pathophysiology

The mechanism leading to the SSS has been debated in the literature, but the leading hypothesis relates to increased stratum corneum permeability.[3] Fundamentally, SSS appears to be an orthergic phenomenon rather than an immunological response.[22] There is a known inverse relationship between corneocyte size and stratum corneum thickness and the permeability of the skin, and changes in this mechanical barrier result in abnormal skin penetration by irritants.[23,24] This phenomenon has been linked to hyperreactors.[25] In addition, low levels of ceramides in the stratum corneum have been linked to increased severity of SLS-induced irritant contact dermatitis, pointing toward barrier compromise in sensitive skin.[26] Seidenari linked self-reported hyperreactivity to decreased skin capacitance (indicating decreased water content), objectively suggesting increased absorption of irritants by the sensitive-skin population.[27] In the same study, increased erythema was objectively measured in hyperreacting subjects suggesting involvement of some baseline vascular component, and leading more recent investigators to propose the involvement of cutaneus sensory innervation in the pathogenesis of SSS.[2]

Clinical Approach

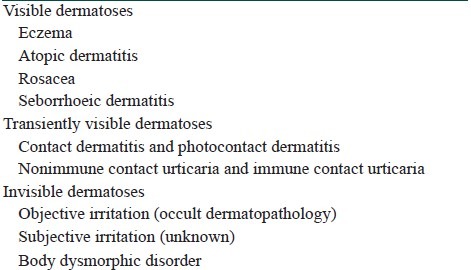

As with many syndromes, the management scheme presented here emphasizes the diagnostic framework [Table 1]. The clinical approach to the SSS demands a thorough process of eliminating obvious as well as more subtle diagnoses. Once the diagnosis is made, deriving the appropriate treatment becomes a relatively simple task. Note that since much of the mechanisms of SSS are unknown, the clinician must be comfortable with a certain degree of ambiguity and uncertainty.

Table 1.

Underlying mechanisms of sensitive skin syndrome

It is reasonable to organize the differential diagnosis by dividing SSS into visible and invisible SSS. Some dermatoses that most clinicians find simple to diagnose may have atypical presentation and as a result lack the ‘expected’ morphology. Eczema, atopic dermatitis, and rosacea are likely the three most common causes of SSS related to barrier defect.[28] Seborrheic dermatitis should probably be included in that category as well.[29] Full discussion of these conditions is beyond the scope of this overview but we will highlight some common clinical features. Careful history, including family history and occupational history, combined with a detailed physical exam will often reveal the diagnosis. In the history particular consideration should be given to culprits such as the masking effect of other topical agents applied by the patient. The physical exam should include scrutiny of the face and scalp for subtle signs of minor inflammation, which are often masked in SSS with underlying endogenous dermatoses.[1] In all of these conditions the patients are likely over-exfoliating their skin and thus exacerbating the barrier dysfunction. Therefore, following specific treatment to halt the acute pathological process, preventing recurrence with a proper skin care regimen is indicated. In eczema and atopic dermatitis, the careful clinician may resort to short-term (2-week) use of corticosteroids to stop the inflammatory process. Calcineurin inhibitors are alternatively indicated for delicate areas on the face.[30] In an effort to control histamine release in atopic dermatitis, antihistamines can be added and a relatively allergen-free environment should be created. In rosacea, the mainstay of treatment is oral and topical antibiotics. In seborrhoeic dermatitis, azoles are the mainstay of treatment and low potency corticosteroids and emollients can be added acutely to treat the inflammatory process.[31,32]

Contact dermatitis (CD) and photocontact dermatitis (PCD), as well as nonimmune contact urticaria (NICU) and immune contact urticaria (ICU), are all conditions that may elicit SSS symptomology, with transient objective findings on physical exam. Therefore, careful testing should be performed. CD and PCD can be visualized with skin patch and photopatch testing. Once the allergen has been identified, avoidance should lead to symptom resolution. Allergen-free products are now available and should be included as part of further skin care regimen in these patients. The main reason why NICU is often a missed diagnosis in patients presenting with the SSS is the transient nature of the reaction. Thus, after testing with small amounts of product on the skin, the patient should be carefully examined using minimal magnification: The lesions will be typically revealed within 20 minutes. Common trigger agents are fragrances (e.g. cinnamic aldehyde) and preservatives such as sorbic and benzoic acids.[1] Once triggers are identified, simple avoidance defines the management. ICU can be demonstrated with open and occluded testing, followed by prick testing with appropriate positive and negative controls if no response is elicited.[33] Various foods, latex, parabens, and other chemicals have been implicated in the causation of ICU.[34]

However, there are cases in which no clinical clue is provided by the physical exam. In these cases, a 2-week trial of appropriate-strength corticosteroid may solve the mystery by pointing to an eczematous process in the case of symptoms resolution. Nonetheless, the careful clinician should consider avoiding prolonged use of topical corticosteroids since there is anecdotal clinical experience of topical corticosteroids inducing SSS[35] and, at least in the case of barrier dysfunction, earlier and complete steroid tachyphylaxis has been demonstrated.[36] If no symptomatic relief is observed, the patient's SSS is likely due to an invisible underlying cause.

The elusive category of invisible causes of SSS comprises subjective and objective irritation. In both of these cases defined by Maibach, no signs are present or can be elicited on the skin. In objective irritation the cause is presumed subclinical inflammation due to occult dermatopathology. In subjective irritation the mechanism is unknown and this diagnosis likely bundles more than one pathological process in it. Interestingly (and clinically frustratingly), Maibach considers subjective irritation to be the most common cause of CIS.[1]

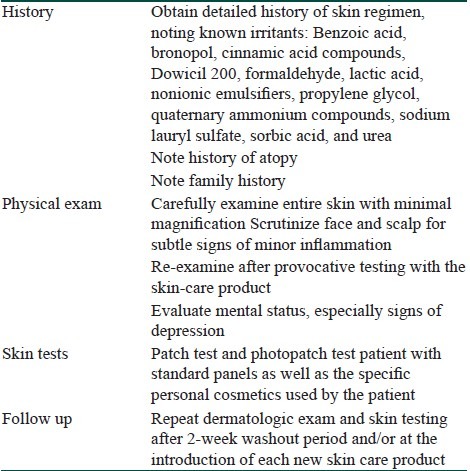

Finally, body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) should always be considered by the dermatologist when assessing skin complaints without objective findings. A recent cross-sectional study found a prevalence of 14% among patients in a cosmetic dermatology clinic.[35] In the context of SSS, dermatologists should be aware that facial irritation complaints without any findings on exam are a common presentation in the dysmorphic patients and therefore extra caution is warranted. Referral to a mental health professional is indicated since these patients are at risk of suicidal behavior.[36,37] Maibach notes that patients suspected of having BDD often require a detailed diagnostic process in order to build the trust needed to safely refer them to the mental health professional.[1] Table 2 summarizes the steps in the evaluation of a patient suspected to have SSS.

Table 2.

Systematic evaluation of sensitive skin syndrome

Management

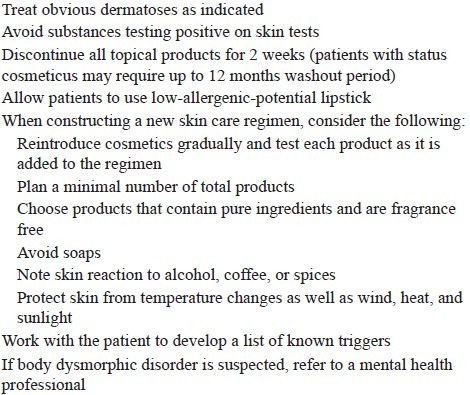

Specific algorithms have been developed for the management of SSS but they are the result of accumulated clinical experience and lack experimental evidence to support their use. Nonetheless, algorithmic thinking may aid in ensuring complete assessment. These algorithms include four basic steps: Discontinuation, assessment, testing, and slow re-introduction. Discontinuation of all topical medication and/or products, as well as elimination of activities and clothing resulting in skin friction, should be initiated and may need to last up to 12 months. The patient should then be assessed (as described above) for the occurrence of any visible dermatoses. If no clear pathology has emerged, rigorous testing is the next step. Testing should include patch and photopatch testing of routine allergens as well as of all of the patient's skin care items. Specific testing for contact urticaria should be a part of the testing protocol. Finally, when all these tests are negative, evaluation of mental status is warranted. The next step in management is slow re-introduction of the ‘minimally necessary’ skin care products. For females, recommend adding low-allergenic- potential cosmetic products one at a time in the following order: Lipstick, face powder, and blush. For all products re- introduced, recommend testing by applying the product to a 2-cm area lateral to the eye for five consecutive nights and documenting the positive and/or negative result. This exhausting process is not only a rational solution from a clinical management standpoint but may also aid in diagnosing the specific culprit in cases of invisible SSS. Table 3 summarizes the general approach to managing SSS.

Table 3.

General approach to managing sensitive skin syndrome

Conclusion

SSS is very common and poses a challenge to physicians and patients alike. We are still far from understanding the underlying mechanisms involved. Therefore, more basic science research is warranted. Understanding the underlying mechanisms may lead to the development of a well-standardized screening test. This will allow clinical studies to rely on objective findings rather than self-reports and this, in turn, may result in more comprehensive and efficient management strategies.

What is new?

1. Fundamentally, SSS appears to be an orthergic phenomenon rather than an immunological response.

2. Female self-perception of sensitivity is consistently increased compared to that of males, yet when put through objective reactivity testing the trend is unclear.

3. It is reasonable to organize the differential diagnosis by dividing SSS into visible and invisible SSS.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Maibach HI. The cosmetic intolerance syndrome. Ear Nose Throat J. 1987;66:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pons-Guiraud A. Sensitive skin: A complex and multifactorial syndrome. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2004;3:145–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2130.2004.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berardesca E, Fluhr JW, Maibach HI. What is sensitive skin? In: Berardesca E, Fluhr JW, Maibach HI, editors. Dermatology: Clinical and Basic Science Series, Sensitive Skin Syndrome. New York: Taylor and Francis Group; 2006. pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saint-Martory C, Roguedas-Contios AM, Sibaud V, Degouy A, Schmitt AM, Misery L. Sensitive skin is not limited to the face. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:130–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher AA. ‘Status cosmeticus’: A cosmetic intolerance syndrome. Cutis. 1990;46:109–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yosipovitch G. Evaluating subjective irritation and sensitive skin. Cosmet Toiletries. 1999;114:41–2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson MK. Intra-individual variations in acute and cumulative skin irritation responses. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;45:75–83. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.045002075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marriott M, Holmes J, Peters L, Cooper K, Rowson M, Basketter DA. The complex problem of sensitive skin. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;53:93–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basketter DA, Griffiths HA. A study of the relationship between susceptibility to skin stinging and skin irritation. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;29:185–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1993.tb03534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Judge MR, Griffiths HA, Basketter DA, White IR, Rycroft RJ, McFadden JP. Variation in response of human skin to irritant challenge. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;34:115–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willis CM, Shaw S, De Lacharrière O, Baverel M, Reiche L, Jourdain R, et al. Sensitive skin: An epidemiological study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:258–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Issachar N, Gall Y, Borell MT, Poelman MC. pH measurements during lactic acid stinging test in normal and sensitive skin. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;36:152–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1997.tb00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Misery L, Sibaud V, Merial-Kieny C, Taieb C. Sensitive skin in the American population: Prevalence, clinical data, and role of the dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:961–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.04884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Misery L, Boussetta S, Nocera T, Perez-Cullell N, Taieb C. Sensitive skin in Europe. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:376–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.03037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson MK. Population differences in acute skin irritation responses. Race, sex, age, sensitive skin and repeat subject comparisons. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;46:86–93. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.460205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lammintausta K, Maibach HI, Wilson D. Irritant reactivity in males and females. Contact Dermatitis. 1987;17:276–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1987.tb01477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Björnberg A. Skin reactions to primary irritants in men and women. Acta Derm Venereol. 1975;55:191–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Modjtahedi SP, Maibach HI. Ethnicity as a possible endogenous factor in irritant contact dermatitis: Comparing the irritant response among Caucasians, blacks, and Asians. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:272–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jourdain R, de Lacharrière O, Bastien P, Maibach HI. Ethnic variations in self-perceived sensitive skin: Epidemiological survey. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;46:162–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.460307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aramaki J, Kawana S, Effendy I, Happle R, Löffler H. Differences of skin irritation between Japanese and European women. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:1052–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wöhrl S, Hemmer W, Focke M, Götz M, Jarisch R. Patch testing in children, adults, and the elderly: Influence of age and sex on sensitization patterns. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:119–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2003.20204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Lacharrière O, Jourdain R, Bastien P, Garrigue JL. Sensitive skin is not a subclinical expression of contact allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:131–2. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.440210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitson N, Thewalt JL. Hypothesis: The epidermal permeability barrier is a porous medium. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 2000;208:12–5. doi: 10.1080/000155500750042808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Machado M, Hadgraft J, Lane ME. Assessment of the variation of skin barrier function with anatomic site, age, gender and ethnicity. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2010;32:397–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2494.2010.00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamami I, Marks R. Structural determinants of the response of the skin to chemical irritants. Contact Dermatitis. 1988;18:71–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1988.tb02742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.di Nardo A, Sugino K, Wertz P, Ademola J, Maibach HI. Sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) induced irritant contact dermatitis: A correlation study between ceramides and in vivo parameters of irritation. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;35:86–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seidenari S, Francomano M, Mantovani L. Baseline biophysical parameters in subjects with sensitive skin. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;38:311–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Draelos ZD. Treatments for sensitive skin: An update. In: Berardesca E, Fluhr Joachim W, Maibach Howard I, editors. Dermatology: Clinical and Basic Science Series, Sensitive Skin Syndrome. New York: Taylor and Francis Group; 2006. pp. 245–53. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maibach HI, Engasser P. Management of cosmetic intolerance syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 1988;6:102–7. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(88)90038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darsow U, Wollenberg A, Simon D, Taïeb A, Werfel T, Oranje A, et al. ETFAD/EADV eczema task force 2009 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:317–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naldi L, Rebora A. Clinical practice. Seborrheic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:387–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0806464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fritsch PO, Reider N. Other eczematous eruptions. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini R, et al., editors. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Mosby: 2008. pp. 197–200. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedmann P, Wilkinson M. Occupational dermatoses. In: Bolongnia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini R, et al., editors. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Mosby: 2008. pp. 236–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henry JC, Tschen EH, Becker LE. Contact urticaria to parabens. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1231–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Personal communication. Lev-Tov H. 2012 Mar [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh S, Gupta A, Pandey SS, Singh G. Tachyphylaxis to histamine-induced wheal suppression by topical 0.05% clobetasol propionate in normal versus croton oil-induced dermatitic skin. Dermatology. 1996;193:121–3. doi: 10.1159/000246225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conrado LA, Hounie AG, Diniz JB, Fossaluza V, Torres AR, Miguel EC, et al. Body dysmorphic disorder among dermatologic patients: Prevalence and clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:235–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]