Abstract

Background:

Chronic urticaria (CU) is defined as urticaria persisting daily as or almost daily for more than 6 weeks and affecting 0.1% of the population. Mast cell degranulation and histamine release is of central importance in the pathogenesis of CU. About 40-50% of the patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria demonstrate an immediate wheal and flare response to intra-dermal injected autologous serum. This led to the concept of autoimmune urticaria.

Aims:

To determine the occurrence, clinical features, associated clinical conditions, comorbidities of autoimmune urticaria and to compare this with chronic spontaneous urticaria. This study aimed to find the frequency of autologous serum skin test (ASST) positive patients among patients with CU and to identify the clinical and laboratory parameters associated with positive ASST.

Materials and Methods:

Prospective correlation study was done on 80 chronic urticaria patients, more than 6 weeks duration, attending outpatient department of dermatology during a period of November 2007 to January 2010. Patients were subjected to ASST, complete blood count, urine routine examination, liver function tests, renal function tests, thyroid function tests, H. pylori antibody tests, C3 and C4 complement level estimation, antinuclear antibody, and urine analysis.

Results:

ASST was positive in 58.75% and negative in 41.25% of the patients, respectively. Out of 33 patients with history of angioedema, 9 (27.3%) patients were in ASST negative group and 24 were in positive group, this was statistically significant. Both groups showed no statistically significant difference for epidemiological details.

Conclusion:

ASST is considered a screening test for an autoimmune urticaria, which decreases the rate of diagnosis of “idiopathic” form of chronic urticaria. Patients with an autoimmune urticaria have more severe urticaria, more prolonged duration, more frequent attacks, and angioedema. Identification of autoimmune urticaria may permit the use of an immunotherapy in severe disease unresponsive to anti-histamine therapy.

Keywords: Angioedema, autoimmune, autologous serum skin test, chronic, urticaria

Introduction

What was known?

ASST positive and ASST negative patients showed no difference in terms of duration of attack, frequency of attacks and angioedema in earlier studies.

Chronic urticaria (CU) is defined as urticaria persisting daily or almost daily for more than 6 weeks or more and affecting 0.1% of the population.[1,2] About 50% of the chronic urticaria patients who demonstrate IgG auto antibodies directed against epitopes expressed on a chain of the high affinity receptor of IgE (FceRI) or IgE itself, often termed as autoimmune urticaria cases, tend to have a high itch and wheal score, systemic symptoms, and other associated autoimmune diseases.[3–5] An angioedema also occurs concurrently with chronic urticaria in 87% of patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU) and is also frequent in autoimmune urticaria.[6] Chronic urticaria is an often disabling condition, which can prevent patient to perform daily activities.[7] Autologous serum skin test (ASST) provides an easy, inexpensive investigation in CU and helps direct attention to underlying systemic auto immune diseases.[8] ASST has a sensitivity of approximately 70% and a specificity of 80% for in vitro basophil histamine release when the serum response is at least 1.5 mm greater than the control saline skin test at 30 min.[9,10]

Materials and Methods

This study included 80 patients of chronic urticaria of more than 6 weeks duration, compliant patients, patients aged above 10 years. Non-compliant patients, patients below the age group of 10, patients on anti-histamines are excluded from the study. In all patients, physical urticaria, food and drug allergies, as well as urticarial vasculitis were ruled out after taking detailed history, relevant laboratory investigations, and biopsy were done when necessary. In all patients, anti-histamines were withdrawn 2 days prior, doxepin 2 weeks prior, corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents were withdrawn 6 weeks prior to ASST.[9–11] Clinical details of all patients were recorded using a standard format. Details including duration of disease in months, duration of individual wheals in hours, frequency of attacks, distribution of wheals, associated systemic symptoms (fever, wheeze, shortness of breath, joint, and abdominal pain), provoking physical factors, food and drug intolerance, seasonal variation and angioedema were recorded.

An informed consent was taken from all patients. Patients were subjected to a physical provocation test and laboratory investigations based on an individual history. In patients with clinical features suggestive of systemic involvement, appropriate laboratory tests were done, these included: Complete blood count (CBC), urine routine examination, liver function tests (LFT), renal function tests (RFT), thyroid function tests (TFT), C3 and C4 complement level estimation, H. pylori antibody tests, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) and ASST. All the patients diagnosed as chronic urticaria were sent to the laboratory, and samples of 1 ml of venous blood were collected in sterile container. Serum was centrifuged.

Samples of serum were brought back to the department, and the test was done. Samples of 0.05 ml of autologous serum and 0.05 ml of 0.9% sterile normal saline was injected separately intradermally into the volar aspect of the right and left forearm with a gap of 2 inches below the flexor region.[5,12]

They were labeled as serum and saline on the respective forearms. Wheal and flare response was measured at 30 minutes. ASST was considered positive if a serum-induced wheal, which was both red and raised, which had a diameter bigger than a saline, induced response by ≥1.5 mm when seen at 30 min. When diagnosis was established as autoimmune and chronic urticaria, all the patients diagnosed as autoimmune urticaria were grouped together as one group, and all the other patients were grouped as chronic spontaneous urticaria. Then, both the groups were compared for their clinical features and their associated comorbidities. Then, the data was analyzed, and conclusion was drawn based on the data, such as what percentage of urticaria population had autoimmune urticaria, of which what percentage had associated clinical features of other comorbidities.

Results

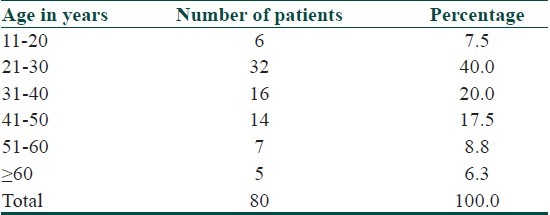

Out of 80 patients enrolled for the study, the minimum age was 14 years and maximum age was 75 years. The average age observed was 35.36 years. Majority of the patients were in reproductive age group [Table 1]. 36 (45%) patients were males, and 44 (55%) patients were females. The male: female ratio is 1:1.22. 39 patients (48.8%) presented within 6 months of onset of disease. The minimum duration of an illness was 2 months while maximum was 144 months. An average duration of illness was 19.93 months. Duration of each attack varied from minimum of half-an-hour to a maximum of more than 12 hours but less than 24 hours. The average duration of each urticarial attack lasted for about 6.5 hours. In 53.75% of the patients, each attack of urticaria lasted for about 6-12 hours.

Table 1.

Age distribution of patients studied

33 (41.3%) patients had history of angioedema. Out of 33 patients, 24 patients had history of angioedema affecting both eyes and lips. Out of 80 patients, 10% of patients had history of difficulty in breathing during attacks of urticaria. 90% patients did not have any history of difficulty in breathing. 33 patients out of 80 had other associated conditions. Out of which, headache was commonest, which was seen in 17 (21.25%) patients, followed by white discharge per vagina in 7 (8.75%), throat pain in 7 (8.75%), sinusitis in 5 (5.46%), abdominal pain in 5 (5.46%), vomiting in 3 (3.75%), fever in 3 (3.75%), diarrhea in 3 (3.75%), urinary tract infection in 2 (2.5%), and rheumatoid arthritis in 1 (1.25%) patient. Out of 80 patients, 13 (16.3%) patients gave history of taking medications. 61.3% (49) of patients did not have any diurnal variations. 23.8% (19) patients had exacerbations in the evening, 10% (8) in the night, 5% (4) patients had in the early morning. 61 (76.3%) patients had no provocative factors. 19 patients had history of provoking factors to various substances such as food, pollen, and drugs. Pollen was the commonest factor seen in 5 (6.3%) patients followed by food substances and drugs like sulfonamides and penicillin. 93.8% (75) of patients had persistent urticaria throughout the year without any variations in seasons. 5 (6.3%) patients had exacerbations in winter season. 18 (22.5%) patients had various medical conditions. Diabetes mellitus was seen in 5 (6.3%) patients, 4 (5%) had gastritis, 3 (3.8%) had hypertension, 2 (2.5%) were hypothyroid. 74 patients did not have any history of surgeries. 6 (7.5%) had undergone surgery. 15 (18.8%) patients had history of an atopy. 65 (81.3%) patients did not have history of atopy. 27 (33.8%) patients had family history of various autoimmune conditions. 66.3% patients did not have any family history of an autoimmune disease.

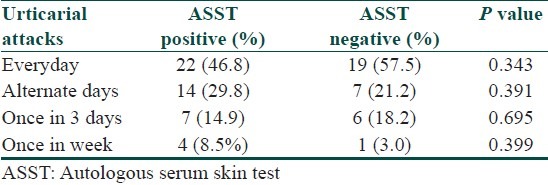

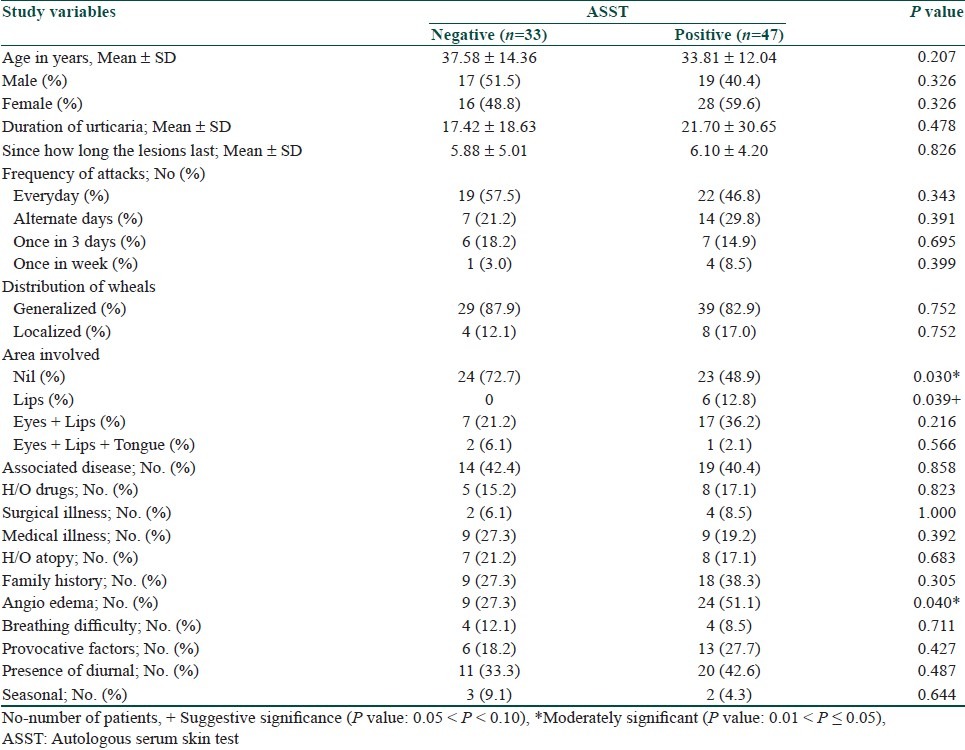

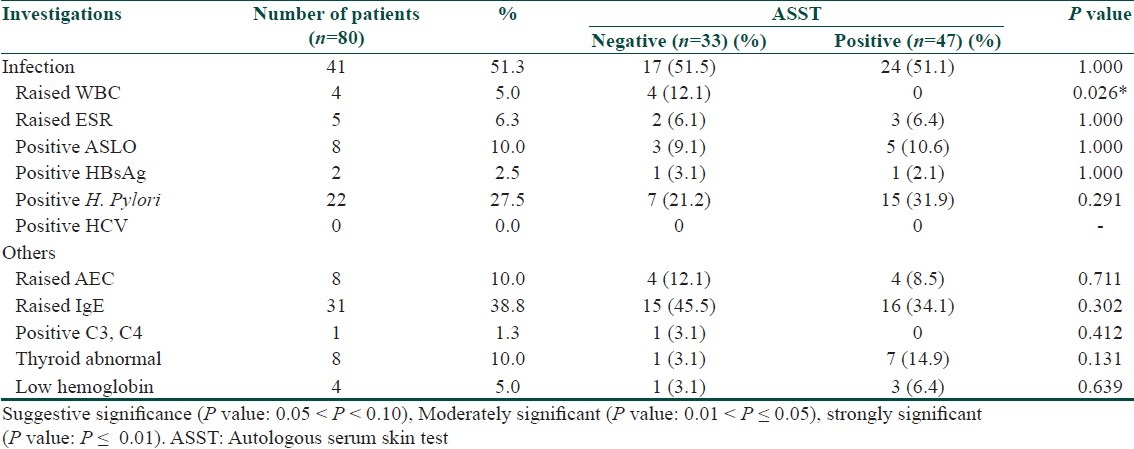

Out of 80 patients, 58.75% were tested positive for ASST, 41.25% were negative. Frequency of urticarial attacks in both ASST positive and ASST negative did not show any statistical significance [Table 2]. The clinical differences between both ASST positive and ASST negative patients did not show any statistical significance, except for angioedema was moderately significant (P = 0.040) [Table 3]. Investigations in both ASST positive and ASST negative patients did not show any statistical significance [Table 4].

Table 2.

Frequency of urticarial attacks in ASST positive and ASST negative patients

Table 3.

Comparison of study variables between ASST positive and ASST negative

Table 4.

Investigations in ASST positive and ASST negative patients

Statistical software

The Statistical software namely SPSS 15.0, Stata 8.0, MedCalc 9.0.1 and Systat 11.0 were used for the analysis of the data, and Microsoft word and Excel have been used to generate graphs, tables, and charts.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistical analysis has been carried out in the present study. Results on continuous measurements are presented on Mean ± SD (Min-Max), and results on categorical measurements are presented in Number (%). Significance is assessed at 5% level of significance. Chi-square/Fisher Exact test has been used to find the significance of study parameters on Categorical scale between 2 or more groups. Student t-test (2-tailed, independent) has been used to find the significance of study parameters on continuous scale between 2 groups Inter group analysis.

Discussion

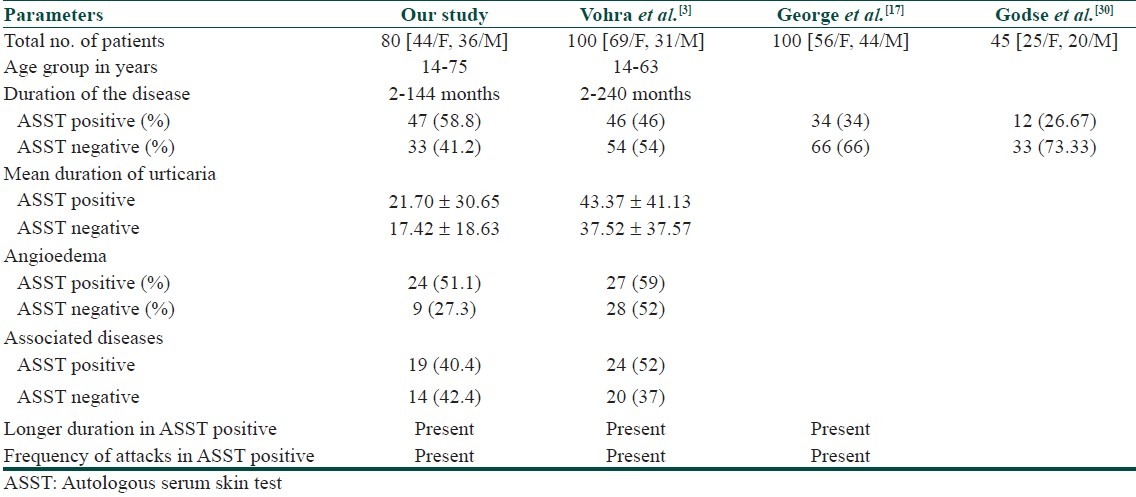

The basophil histamine release assay is currently the gold standard for detecting these functional auto-antibodies in the serum of patients with chronic urticaria. However, this bioassay is difficult to standardize because it requires fresh basophils from healthy donors, is time-consuming and it remains confined to research centers. Western blot, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and flow cytometry may be useful for screening in the future, but they need to be validated. ASST is the simplest and the best in vivo clinical test for detection of basophil histamine releasing activity. ASST is simple, semi-invasive, inexpensive, and easy to perform. Results can be obtained within 30 minutes. Draws attention towards underlying systemic autoimmune and infective conditions. Provides evidence for rational use of immunomodulators to modify the course of chronic urticaria. The ASST positivity of 58.75% in our patients appears comparable with the 27-60% positivity reported previously.[3,13–21] This finding was comparable with other studies done by various authors and also the clinical parameters in ASST positive and negative patients [Table 5]. In this study, patients with ASST positive on further evaluation did not show any significance with H. pylori antibodies, thyroid antibodies, ANA. Duration of the disease was significantly longer in patients with positive ASST than in patients with negative ASST in studies done by Sabroe et al.[9] and by Azim et al.[22] These findings suggest us that it is difficult to control chronic autoimmune urticaria (CAU) as stated by Boguniewicz,[23] and in other chronic urticarias, underlying factors such as infections, drugs, allergies are keeping the disease active. In our study, we used various parameters such as diurnal variations, family history of autoimmunity, seasonal variations, associations with medical conditions, drugs; all these parameters did not have any significance in the study. These findings were similar to a study done by George et al.[17] The above findings suggest us that patient cannot be distinguished clinically.

Table 5.

Comparison with other studies

The association of chronic urticaria with thyroid autoimmunity has been studied by Leznoff et al.[24] and postulated that thyroid autoimmunity may play a role in the pathogenesis of chronic urticaria and angioedema. A study done by Noemi Bakos et al.[16] observed a relationship between autoimmune urticaria and autoimmune thyroiditis. He reported a possible role of H. Pylori in triggering autoimmune urticaria in at least a select group of patients. In a study done by Krupashankar et al.[8] significant higher incidence of H. pylori antibodies and thyroid antibodies were detected in ASST positive patients in comparison to ASST negative patients. Autoimmune diseases like thyroid disease, vitiligo, diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, and rheumatoid arthritis were reported more commonly in patients with autoimmune urticaria.[25,26] However, in contrast with previous studies, George et al.[17] and our study did not find any difference in the incidence of thyroid disease. Studies of the diurnal distribution of pruritus in chronic urticaria revealed that an itching is most prominent in the evening and at night; it is an important consideration when outlining a treatment strategy. The cause of the nocturnal preponderance is unclear but may be due to warmth of the skin and to psychophysiological factors.[27–28]

Immunomodulatory drugs, while their use is not justified in chronic idiopathic urticaria (except in anti-histamine refractory chronic urticaria cases), are therapeutic benefit in recalcitrant to therapy autoimmune urticaria patients having significantly impaired quality life.[29] The present study has evaluated 80 patients with CU by autologous serum skin testing and compared the clinical features of patients with positive and negative ASST results.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that ASST positive and ASST negative groups showed no statistically significant difference for epidemiological details, except for the duration of the disease, frequency of attacks, diurnal variation, and angioedema.

What is new?

Our study suggests that ASST positive and ASST negative groups showed significant difference in terms of duration, frequency of attacks and angioedema.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Goh CL, Tan KT. Chronic autoimmune urticaria: Where we stand? Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:269–74. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.55640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greaves MW. Chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1767–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506293322608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vohra S, Sharma NL, Mahajan VK, Shanker V. Clinicoepidemiologic features of chronic urticaria in patients having positive versus negative autologous serum skin test: A study of 100 Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:156–9. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.77454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabroe RA, Greaves MW. Chronic idiopathic urticaria with functional autoantibodies: 12 years on. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:813–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grattan CE. Autoimmune urticaria. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2004;24:163–81. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greaves MW, Sabroe RA. Allergy and the skin. BMJ. 1998;316:1447–50. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7138.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godse KV. Quality of life in chronic urticaria. Indian J Dermatol. 2006;51:155–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krupashankar DS, Ramnane M, Rajouria EA. Etiological approach to chronic urticaria. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:33–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.60348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabroe RA, Grattan CE, Francis DM, Barr RM, Black AK, Greaves MW. The autologous serum skin test: A screening test for autoantibodies in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:446–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konstantinou GN, Asero A, Maurer M, Sabroe RA, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Grattan CE. EAACI/GA2 LEN task force consensus report: The autologous serum skin test in urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1256–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vohra S, Sharma NL, Mahajan VK. Autologous serum skin test: Methodology, interpretation and clinical applications. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:545–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.55424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan AP. Chronic urticaria: Pathogenesis and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:465–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabroe RA, Fiebiger E, Francis DM, Maurer D, Seed PT, Grattan CE, et al. Classification of anti-FceRI and anti-IgE autoantibodies in chronic idiopathic urticaria and correlation with disease severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:492–9. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.126782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toubi E, Kessel A, Avshovich N, Bamberger E, Sabo E, Nusem D, et al. Clinical and laboratory parameters in predicting chronic urticaria duration: A prospective study of 139 patients. Allergy. 2004;59:869–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Donnell BF, Francis DM, Swana GT, Seed PT, Black AK, Greaves MW. Thyroid autoimmunity in chronic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:331–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakos N, Hillander M. Comparison of chronic autoimmune urticaria with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:613–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.George M, Balachandran C, Prabhu S. Chronic idiopathic urticaria: Comparison of clinical features with positive autologous serum skin test. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:105–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.39690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nettis E, Dambra P, D’Oronzio L, Cavallo E, Loria MP, Fanelli M, et al. Reactivity to autologous serum skin test and clinical features in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:29–31. doi: 10.1046/j.0307-6938.2001.00962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fusari A, Colangelo C, Bonifazi F, Antonicelli L. The autologous serum skin test in the follow-up of patients with chronic urticaria. Allergy. 2005;60:256–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godse K. Methotrexate in autoimmune urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baskan EB, Turker T, Gulten M, Sukran T. Lack of correlation between Helicobacter pylori infection and autologous serum skin test in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:993–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boguniewicz M. The autoimmune nature of chronic urticaria. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2008;29:433–8. doi: 10.2500/aap.2008.29.3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leznoff A, Josse RG, Denburg J, Dolovich J. Association of chronic urticaria and angioedema with thyroid autoimmunity. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:636–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabroe RA, Seed PT, Francis DM, Barr RM, Black AK, Greaves MW. Chronic idiopathic urticaria: Comparison of the clinical features of patients with and without anti-FcεRI or anti-IgE autoantibodies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:443–50. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Donnell BF, Lawlor F, Simpson J, Morgan M, Greaves MW. The impact of chronic urticaria on the quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greaves MW. Recent advances in pathophysiology and current management of itch. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2007;36:788–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yosipovitch G, Greaves MW, Schmelz M. Itch. Lancet. 2003;361:690–94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inamadar AC, Palit A. Management of autoimmune urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:89–91. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.39686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Godse KV. Autologous serum skin test in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:283–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azim ZA, Mongy SE, Salem H. Autologous serum skin test in chronic idiopathic urticaria: Comparative study in patients with positive versus negative test. J Egypt Women Dermatol Soc. 2010;7:129–33. [Google Scholar]