Abstract

Background:

The incidence of tattoos has been increased markedly during the last 20 years.

Aims:

To analyze the patient files for severe adverse medical reactions related to tattooing.

Settings:

Academic Teaching Hospital in South-East Germany.

Materials and Methods:

Retrospective investigation from March 2001 to May 2012.

Results:

The incidence of severe adverse medical reactions has been estimated as 0.02%. Infectious and non-infectious severe reactions have been observed. The consequences were medical drug therapies and surgery.

Conclusions:

Tattooing may be associated with severe adverse medical reactions with significant morbidity. Regulations, education and at least hygienic controls are tools to increase consumer safety.

Keywords: Abscess formation, atypical mycobacteria, body art, edema, granulomatous reaction, multiresistant staphylococcus aureus, scarring alopecia, tattoo, ulceration

Introduction

What was known?

Tattooing is getting more popular. Motives for tattooing are complex. Understanding of real health risk is limited.

Body art or body modification consists of various techniques to modify appearance and/or to express individuality. In history, tribal art and religions used the procedures. In more recent times, sailors, soldiers, prison inmates and gang members identified themselves by the use of body art. Just at the turn of the century, body art gained tremendous popularity and became a part of fashion and anti-fashion, mass culture and self-portraying.[1–4]

Major types of body art include painting and tattooing, piercing, scarring and branding, just to name a few. All of them might be accompanied by adverse effects. In the present study, we will focus on tattooing and severe medical adverse effects only.

Materials and Methods

We analyzed the files of the Department of Dermatology and Allergology, Academic Teaching Hospital Dresden-Friedrichstadt from March 2001 to May 2012 for adverse reactions after tattooing leading to medical treatment. The city of Dresden is the capital of Saxony, with about half a million inhabitants. We excluded contact allergic reactions to false Henna tattoos and minor temporary reactions.

Results

The following case series represents the identified cases and types of severe adverse reactions due to tattooing. Based on the numbers of patients treated per annum, the incidence is estimated as 0.02%. Two patients, i.e. no. 4 and no. 7, had been published in case reports before.[5,6]

Local persistent inflammatory reaction

A 27-year-old, otherwise healthy female, presented with a circumscribed inflammatory lichenoid skin reaction in an older tattoo on her foot that developed about 3 weeks after completion with red ink. The reaction was limited to those areas tattooed red but persistent [Figure 1a and b].

Figure 1.

Persistent lichenoid reaction to red ink. (a) Overview, (b) detail

Patch testing was not possible as the ink could not be identified. Based on clinical findings, the reaction was classified as persistent inflammatory foreign body reaction, although an allergic reaction to red ink components was suspected. Topical corticosteroids were prescribed.

Granulomas followed by acute facial edema

A 45-year-old female presented with pruritic nules in a pre-existent black permanent tattoo that developed within 2 weeks after color-correction using a red ink [Figure 2a]. She was treated with topical corticosteroids but stopped regular use after partial remission. Within another week, she presented with an acute facial edema [Figure 2b]. Systemic corticosteroids were prescribed and remission was seen the next week.

Figure 2.

(a) Granulomatous reaction, followed by (b) delayed facial edema

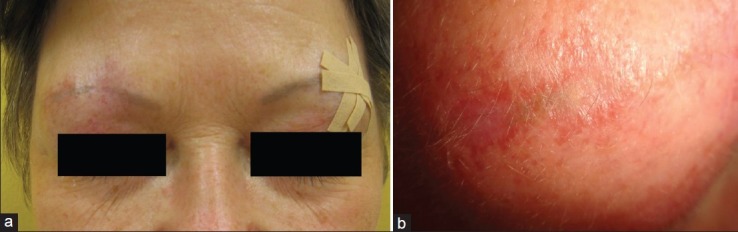

Granulomas with persistent edema and scarring alopecia

A 62-year-old, insulin-dependent diabetic female developed granulomas and glabellar edema with delayed scarring alopecia of the eyebrow 3 years after tattooing for eyebrow permanent make-up [Figure 3a and b]. Histopathological examination of a deep skin biopsy revealed epithelioid granulomas of the whole dermis and giant cells of both the Langhans and foreign body-type accompanied by perivascular and interstitial lympho-histiocytic inflammatory infiltrates. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for atypical mycobacteria was negative. Acid fast bacteria were not found. Laboratory investigations showed an increased concentration of angiotensin-converting enzyme of 124.0 U/L (normal range: 8–53). T-SPOT tuberculosis test was negative. Thoracic X-ray was unremarkable.

Figure 3.

(a) Granulomatous reaction, followed by (b) scarring alopecia

The diagnosis of sarcoidal reaction after permanent tattooing was made. Topical betamethasone cream was prescribed with delayed response.

Persistent inflammatory granulomatous reaction with erythema nodosum

A 17-year-old healthy female presented with a severe partly bullous inflammatory reaction with marked circumscribed edema, shivering, nausea and vomiting a couple of days after tattooing with a red ink [Figure 4a]. She had had a black tattoo for months without any adverse events.

Figure 4.

(a) Intense inflammatory reaction to red ink, followed by (b) erythema nodosum

Patch test with German standard series, textile dyes, leather, dental materials and topical compounds were all negative. A diagnostic biopsy demonstrated a dermal granulomatous reaction with some foreign body-type giant cells and macrophages accompanied by a dense lymphohistocytic inflammatory infiltrate.

We prescribed topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus 0.1% ointment with delayed response.

Two months later, she developed general malaise with painful nodules on the pretibial lower legs with raised temperature (between 38 and 39°C) [Figure 4b]. Laboratory investigations demonstrated elevated C-reactive protein of 27.5 mg/L (normal range <5), and the blood sedimentation rate was 58 in the first hour. Thoracic X-ray was unremarkable.

We made the diagnosis of erythema nodosum and prescribed 40 mg methyl prednisolone/day. After general health improvement, we tapered down the dose. She recovered within 3 weeks.

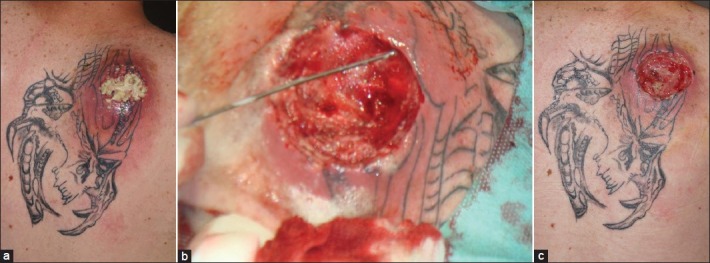

Severe acute absceding infection

A 31-year-old male presented with a painful abscess formation on the right shoulder. He felt general malaise and pain. The oozing lesion was situated within the incomplete tattoo [Figure 5a].

Figure 5.

Abscess formation, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus positive. (a) Initial presentation, (b) after abscess surgey, (c) after systemic antibiosis and negative pressure wound therapy

A swap was taken from it for bacterial culture, which demonstrated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). We treated him with a combination of systemic antibiosis and surgery [Figure 5b]. The large resulting defect after de-roofing the abscess was further treated by vacuum-assisted closure, resulting in decrease of wound depth and area [Figure 5c].

Severe chronic infection

A 46-year-old female presented with several nodules on the left side of the forehead and temple. She reported that these nodules had developed about 8 weeks after she visited a parlour saloon in South Asia for brow permanent make-up. The nodules were arranged in a sporotrichoid pattern [Figure 6a]. Pre-treatment with topical and systemic antibiosis and topical corticosteroids had failed.

Figure 6.

Sporotrichoid atypical mycobacteriosis. (a) Before triple therapy and (b) at the end of triple therapy

Microbial swaps for bacterial cultures remained negative. A deep biopsy was performed for microbiology and histopathology. Histopathology disclosed a chronic dermal and subdermal granulomatous reaction with giant cells of Touton type and numerous foam cells. Epithelioid histiocytes were arranged around a leukocyte-rich abscess. Acid-fast bacteria were not found. PCR identified Mycobacterium haemophilum. Cultures for tuberculosis were all negative.

The diagnosis of atypical mycobacteriosis was confirmed and a triple antibiosis (rifampicin, clarithromycine and ciprofloxacin) was initiated. After 3 months, we switched to rifampicin monotherapy for another 3 months, and gained a complete remission [Figure 6b].

Cutaneous ulceration after tattoo

A 33-year-old male presented with a superficial ulceration about 4 weeks after a red tattoo on his forearm [Figure 7]. Microbial swabs remained negative. His medical history was uneventful. He was of good general health, and no reason for this uncommon reaction could be identified. We suggested a local allergic reaction with transdermal elimination of the pigment. He refused a biopsy.

Figure 7.

Large ulceration in a tattoo

Discussion

Tattooing has become a common procedure in the Western World, no longer restricted to outlaws, prisoners, sailors or gang members. It is part of a culture using body modifying techniques. Although tattoos are more frequent among youngsters and young adults, there seems to be no age-limit. Both tattooing and removal of tattoos has become a business, with the latter less successful but more expensive than the former.[7]

With the growing interest in tattoos, there is also a need of awareness for unwanted adverse effects. Concerns are growing by official bodies and dermatologists.[8,9] Foreign body reactions, mostly of the granulomatous type or pseudolymphomatous type, are seen commonly. Most of them resolve either spontaneously or after treatment with topical corticosteroids.[10,11] Sometimes, they can cause more severe problems like uveitis, disseminated granulomatous reactions or perforating granulomatous reaction.[12–14] We observed long-term problems with edema formation or erythema nodosum development.[5] Laser treatment in such cases may increase the risk of further adverse effects.[15]

Although the risk of infection is known for a long time, new germs possess new risks. Ink and other tattoo equipment are related possible infections.[16] Community-acquired, lifestock-associated and healthcare-associated MRSA infection have become a reality. In Germany, about 20% of Staphylococcus aureus cultures are MRSA positive. The incidence in 2011 has been calculated as high as 5 per 100,000 inhabitants.[17] We described an MRSA– abscess after tattooing. Unsterile equipment and ineffective measures for infection control have been identified as major causes.[18] Tattoo-acquired MRSA has been identified as a cause of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in a 16 year-old boy.[19]

For a long time, atypical mycobacterial infections were seen only in high-risk populations such as patients after organ transplantation, immunodeficient patients or diabetic patients, etc.[20] In the last decade, the number of immunocompetent patients affected by atypical mycobacterial disease is growing.[21] This has also led to growing numbers of tattoo-induced infections, with ink as the major source of infection.[22–27]

Ulcers are uncommon adverse effects of tattooing. Two cases have been observed in patients with leukemia.[28,29] We were unable to identify a definite cause in our case, but suppose that an allergic reaction to the red ink might have been responsible.

The series of patients demonstrates that severe adverse reactions can be seen after tattooing, and physicians should be aware of this. Furthermore, there is a need of regulations for inks and other equipment and for parlour or tattoo saloons for consumer safety.[7]

What is new?

Tattooing has become a risk factor for severe adverse reactions related to inks, procedures and settings. Both infectious and non-infectious adverse reactions have been observed among otherwise healthy people with significant morbidity.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Rubin A. Artistic transformation of the human body. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 1988. Marks of Civilization. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sweetman P. Anchoring the (postmodern) self? Body modification, fashion and identity. Body Soc. 1999;5:51–76. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gröning K. A cultural history of body art. 2nd ed. Munich: Frederking and Thaler; 2001. Decorated Sin. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ecco U. Storia della Belleza. Milano: Bompiani; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wollina U, Gruner M, Schönlebe J. Granulomatous tattoo reaction and erythema nodosum in a young woman: Common cause or coincidence? J Cosmet Dermatol. 2008;7:84–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2008.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wollina U. Nodular skin reactions in eyebrow permanent makeup: Two case reports and an infection by Mycobacterium haemophilum. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10:235–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2011.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wollina U, De Cuyper C. Tattoo removal. In: Maibach H, Gorouhi F, editors. Evidence Based Dermatology. 2nd ed. Shelton/ CT: PMPH-USA; 2011. pp. 557–70. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortiz AE, Alster TS. Rising concern over cosmetic tattoos. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:424–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kluger N. Cutaneous complications related to permanent decorative tattoing. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010;6:363–71. doi: 10.1586/eci.10.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones B, Oh C, Egan CA. Spontaneous resolution of a delayed granulomatous reaction to cosmetic tattoo. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:59–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kluger N, Vermeulen C, Moguelet P, Cotten H, Koeb MH, Balme B, et al. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma) in tattoos: A case series of seven patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:208–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barabasi Z, Kiss E, Balaton G, Vajo Z. Cutaneous granuloma and uveitis caused by a tattoo. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2008;120:18. doi: 10.1007/s00508-007-0900-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulz J, Lonsdorf A, Jappe U, Hartschuh W. Disseminated granulomatous type IV reaction after a tattoo. Hautarzt. 2008;59:567–70. doi: 10.1007/s00105-007-1428-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sweeney SA, Hicks LD, Ranallo N, Iv NS, Soldano AC. Perforating granulomatous dermatitis reaction to exogenous tattoo pigment: A case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011 doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e318209f117. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaur RR, Kirby W, Maibach H. Cutaneous allergic reactions to tattoo ink. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8:295–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2009.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kluger N, Terru D, Godreuil S. Bacterial and fungal survey of commercial tattoo inks used in daily practise in a tattoo parlor. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1230–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becker K, Sunderkötter C. Skin infections with MRSA. Epidemiology and clinical features. Hautarzt. 2012;63:371–80. doi: 10.1007/s00105-011-2255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections among tattoo recipients--Ohio, Kentucky, and Vermont, 2004-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:677–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chalmers D, Marietti S, Kim C. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in an adolescent. Urology. 2010;76:1472–4. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer TW, Assefa S, Bauer HI, Graefe T, Scholz M, Pfister W, et al. Diagnostic odyssey of a cutaneous mycobacteriosis rare in central Europe. Dermatology. 2002;205:289–92. doi: 10.1159/000065854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhambri S, Bhambri A, Del Rosso JQ. Atypical mycobacterial cutaneous infections. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kay MK, Perti TR, Duchin JS. Tattoo-associated Mycobacterium haemophilum skin infection in immunocompetent adult, 2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1734–6. doi: 10.3201/eid1709.102011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Binić I, Janković A, Ljubenović M, Gligorijević J, Jančić S, Janković D. Mycobacterium chelonae infection due to black tattoo ink dilution. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:404–6. doi: 10.2165/11589500-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell CB, Isenstein A, Burkhart CN, Groben P, Morrell DS. Infection with Mycobacterium immunogenum following a tattoo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:e70–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamsch C, Hartschuh W, Enk A, Flux K. A Chinese tattoo paint as a vector of atypical mycobacteria-outbreak in 7 patients in Germany. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:63–4. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drage LA, Ecker PM, Orenstein R, Phillips PK, Edson RS. An outbreak of Mycobacterium chelonae infections in tattoos. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:501–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kluger N, Muller C, Gral N. Atypical mycobacteria infection following tattooing: Review of an outbreak in 8 patients in a French tattoo parlor. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:941–2. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.7.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tendas A, Niscola P, Barbati R, Abruzzese E, Cuppelli L, Giovannini M, et al. Tattoo related pyoderma/ectyma gangrenous as presenting feature of relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia: An exceptionally rare observation. Injury. 2011;42:546–7. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobson S, Martin DB, Deng A, Cooper JZ. Pyoderma gangrenosum following tattoo placement in a patint with acute myelogenous leukemia. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:58–60. doi: 10.1080/09546630701713501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]