Abstract

Many of the more than 20 mammalian proteins with N-BAR domains1-2 control cell architecture3 and endocytosis4-5 by associating with curved sections of the plasma membrane (PM)6. It is not well understood whether N-BAR proteins are recruited directly by processes that mechanically curve the PM or indirectly by PM-associated adaptor proteins that recruit proteins with N-BAR domains that then induce membrane curvature. Here, we show that externally-induced inward deformation of the PM by cone-shaped nanostructures (Nanocones) and internally-induced inward deformation by contracting actin cables both trigger recruitment of isolated N-BAR domains to the curved PM. Markedly, live-cell imaging in adherent cells showed selective recruitment of full length N-BAR proteins and isolated N-BAR domains to PM sub-regions above Nanocone stripes. Electron microscopy confirmed that N-BAR domains are recruited to local membrane sites curved by Nanocones. We further showed that N-BAR domains are periodically recruited to curved PM sites during local lamellipodia retraction in the front of migrating cells. Recruitment required Myosin II-generated force applied to PM connected actin cables. Together, our study shows that N-BAR domains can be directly recruited to the PM by external push or internal pull forces that locally curve the PM.

N-BAR domains are versatile membrane-binding regulatory elements that function in a wide range of cellular processes including regulation of cortical actin structures3 and Clathrin-mediated endocytosis4-5. Although the cellular functions of many N-BAR domain proteins have been extensively studied, the fundamental chicken and egg causality dilemma whether they primarily sense or form curvature is not resolved. This question applies to all curvature binding domains but is particularly relevant for N-BAR domain proteins where in vitro assays showed that they selectively bind to6 as well as form7 membranes of high positive curvature. During endocytosis, where N-BAR domains have been most extensively studied, the N-BAR domain proteins Amphiphysin1, Endophilin2, and Bin2 are only recruited after the assembly of Clathrin-coated pits in a step that preceded vesicle scission8. This raised the question whether N-BAR domain proteins are recruited directly by curved membranes created by Clathrin-mediated formation of a tubular neck or indirectly by first binding to adaptor proteins that then recruit N-BAR domains to curve the membrane. Similarly, it is not clear how N-BAR domain proteins that bind N-WASP9-10 and other actin binding proteins11-12 are recruited to actin rich regions of the PM to then in turn regulate the actin architecture.

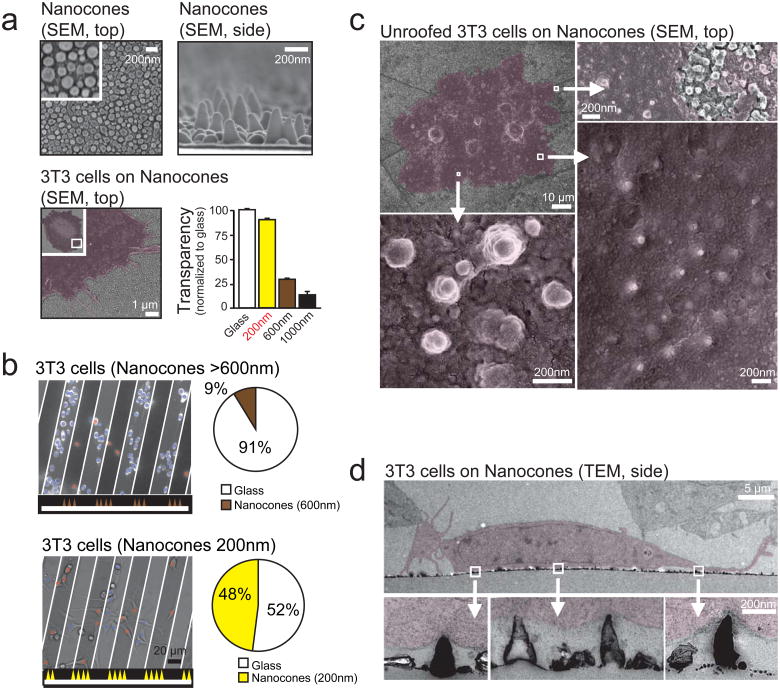

Our study aimed to distinguish between sensing and forming curved membranes by investigating recruitment of N-BAR domain protein to the PM in living cells. We focused on two examples of N-BAR domains, the one from Nadrin23,13, a regulator of actin polymerization, and the one from Amphiphysin14, a regulator of endocytosis. We developed a method to directly deform the PM in live cells using cone-shaped tinoxide nanostructures14 (Nanocones). The top panels in Fig. 1a show top and side scanning electron microscopy views of the formed Nanocones and the bottom left panel shows a cell growing on top of the Nanocone surface.

Figure 1. Nanocones induce inward curved PM deformations at the basal PM of adherent cells.

(a) Scanning electron micrographs of Nanocones on glass substrate shown from the top (top, left) and the side (top, right). SEM of 3T3 cells (red) grown on 200nm Nanocones (bottom, left). Transparency of Nanocones decreases with increasing cone height (bottom, right). For each height, transparency was measured at 8 different regions of the sample. Error bars represent s.e.m. of the mean value. (b) 3T3 cells cultured on 20μm wide stripes of 600nm Nanocones (top) and 200nm Nanocones (bottom). The sawtooth symbols at the bottom of the panels and the white lines depict the location of the Nanocone stripes. After 48h cell density on 600nm cones (brown) is significantly lower compared to adjacent glass surface while no changes are visible for 200nm Nanocones (yellow). Analysis of cell density for Nanocones of 600nm (n=1484 cells, top) and 200mn (n=780 cells, bottom) height are shown to the right. (c) Scanning electron micrographs of the inner side of the PM of cells grown on 200nm Nanocones. Cells were sonicated to remove all but the PM of cells grown on Nanocones (red). Note the Nanocone-induced deformation of the PM (d) Transmitted electron micrographs of 3T3 cells grown on 200nm Nanocones. Cells are colored in red. Note that Nanocones do not penetrate the PM. Scale bars; (a), top panels 200nm, bottom panel 1μm; (b), 20 μm; (c), top left panel 10 μm, all other 200nm; (d), top panel 5 μm, bottom panels 200nm.

We tested an array of cone sizes that can be formed by this process and found an optimal height of 200 nm with a diameter of 50 nm at the base. 200 nm Nanocones had a 90% transparency compared to glass without Nanocones (Fig. 1a, bottom right). When cultured on 200 nm but not on 600 nm Nanocones, cells showed no significant preference between Nanocone and flat surfaces (Fig. 1b) and freely migrated across 20 μm wide bands of Nanocones (data not shown). When culturing cells on these Nanocones, we found small diameter positively curved sections (inward bend) in the basal PM of ‘unroofed’ cells in scanning electron micrographs (Fig. 1c), and in transmission electron micrographs of cross-sections of the basal PM (Fig. 1d).

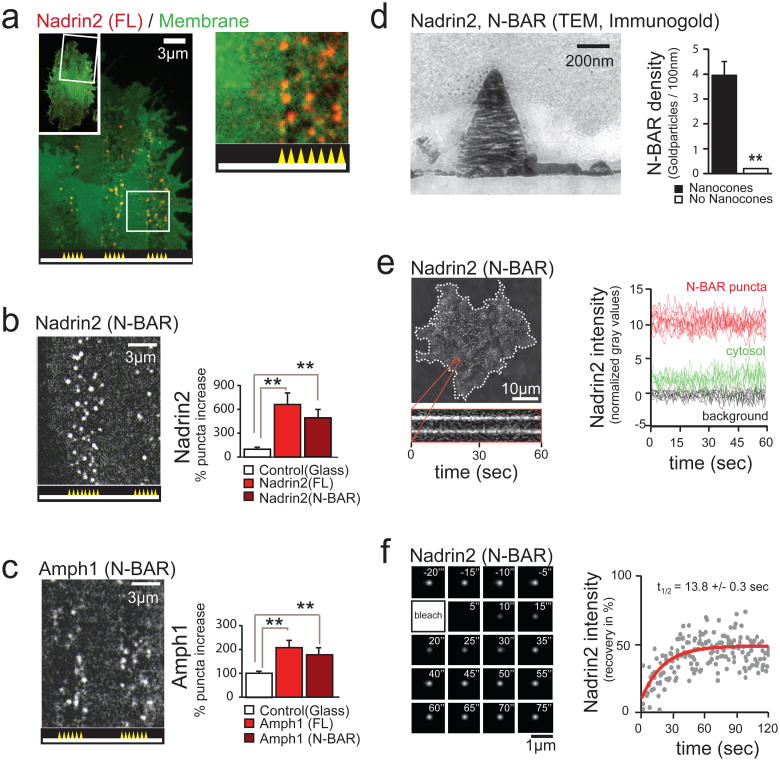

To compare the effect of Nanocone-induced PM curvatures on N-BAR domain recruitment within the same cell, we designed a pattern of 3 μm-wide stripes, alternating between smooth and Nanocone-coated surfaces, plated 3T3 cells expressing fluorescently tagged N-BAR proteins on these patterned nanostructures, and imaged them with a confocal microscope. Markedly, we found puncta selectively over Nanocone stripes when we expressed the YFP-conjugated N-BAR protein Nadrin2 (Fig. 2a). Control experiments showed that the average local increase in Nadrin2 intensity in puncta was 113 +/− 9% over a uniform cytosolic background while a PM marker increased at the same sites only by 45 +/ −3%, arguing that Nadrin2 is recruited to local sites within the PM. A correlation analysis resulted in the same conclusion (Supplementary Figs. S1a, b).

Figure 2. Nanocone-induced membrane deformation triggers N-BAR domain recruitment to the PM.

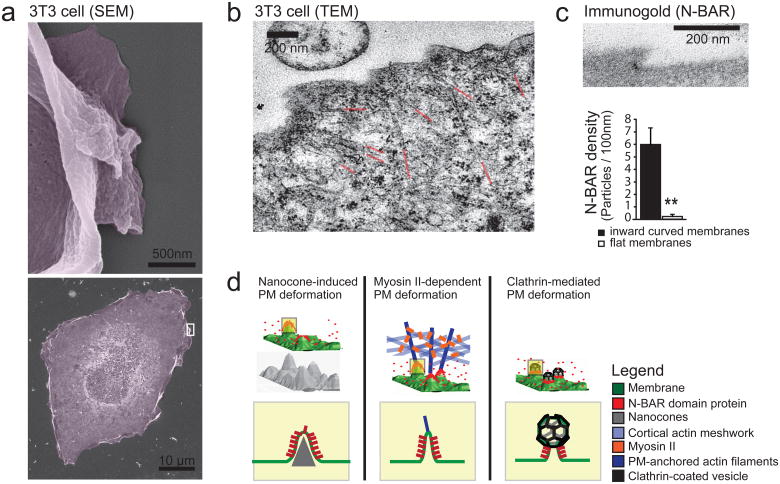

(a) Nadrin2 forms puncta over Nanocones. 3T3 cells were grown on 3μm wide stripes of Nanocones and transfected with Nadrin2 (red) together with membrane marker CAAX (green). Nadrin2 puncta formation was selectively observed over Nanocone stripes. Magnification of a selected region (white box) is shown next to it. (b, c) The N-BAR domain is sufficient for puncta formation. Quantitative analysis of the increase in puncta density induced by Nanocones for full length (FL, light red, n=14 cells) and the isolated N-BAR domain (N-BAR, dark red, n=12 cells) of Nadrin2 (b) and full length (FL, light red, n=10 cells) and the isolated N-BAR domain (N-BAR, dark red, n=12 cells) of Amphiphysin1 (c), respectively. Error bars represent s.e.m. of the mean value (d) Transmitted electron micrograph show that the N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 accumulates on membrane deformations induced by Nanocones. 3T3 cells were transfected with fluorescently tagged N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 fixed and incubated with primary antibody directed against the fluorescent tag. Note that gold-conjugated secondary antibody accumulate over Nanocone-induced inward membrane deformations. Immunogold density was measured over Nanocones (n = 25) where deformation of the PM was observed and compared to adjacent regions within the same image. Error bars represent s.e.m. of the mean value. (e) Nanocone-induced N-BAR domain puncta of Nadrin2 are stationary and long-lived. 3T3 cell plated on Nanocones was transfected with fluorescently tagged N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 and imaged every 500ms for 60 seconds. Kymograph of two representative puncta (orange) is shown below. To the right, a graph depicting traces of individual N-BAR domain puncta (red), cytosol (green) and background (black) are shown. (f) FRAP analysis indicates a stable, long-lasting and a dynamic fraction of comparable sizes over individual Nanocones. Magnified area showing a time-series following a single Nanocone-induced N-BAR domain accumulation through a FRAP cycle (top) and analysis of multiple experiments (bottom) are shown. Scale bars (a-c), 3 μm; (d), 200nm; (e), 10μm; (f), 1 μm; ** P < 0.01.

We then showed that the N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 is sufficient to mediate the punctuate recruitment to the regions with Nanocone stripes (Fig. 2b). In a quantitative single cell analysis, full-length protein and isolated N-BAR-domain generated significant more puncta in the PM over Nanocone stripes compared to the PM over the flat surfaces (Fig. 2b, right panel). This recruitment by Nanocone stripes was not restricted to the N-BAR domain of Nadrin2, but also applied to the isolated N-BAR domain of Amphiphysin1 (Fig. 2c).

Using electron micrographs, we then validated the precise localization of the N-BAR domain over Nanocones. Staining cells transfected with the YFP-tagged N-BAR domain of Nadrin 2 with an antibody directed against the fluorescent tag showed a significant enrichment of gold particles over Nanocones (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Fig. S1c). Next, we measured the persistence of N-BAR domain puncta over Nanocones in live cells. We found the puncta themselves to be stable for periods longer than 1 minute (Fig. 2e) whereas about half of the BAR domains within the puncta exchanged with a time constant of 14 seconds, as shown in fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments (Fig. 2f).

Since many N-BAR domain proteins have roles in endocytosis4-5, we determined, as a control, whether the observed puncta reflect endocytotic sites that might be induced by Nanocones. We did not observe a Nanocone-dependent increase in the average endocytosis rate (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Although, Clathrin light chain and Dynamin both enriched over stripes of Nanocones (Supplementary Figs. S2b, c), co-expression experiments with Nadrin2 and Clathrin light chain showed only minimal overlap (Supplementary Fig. S2d), arguing that N-BAR domain recruitment by Nanocones can be induced independent of endocytosis. This low correlation was confirmed in a spatial cross-correlation analysis where the co-localization of the near identical CFP-tagged Nadrin2 and YFP-tagged Nadrin2 was used as a reference (Supplementary Figs. S2e, f). Tracking individual CFP-Clathrin light chain puncta over Nanocones over time provided no evidence for sequential co-localization, ruling out that N-BAR domain recruitment follows Clathrin accumulation with a delay (Supplementary Fig. S2g). Together, this argues that Nanocones provide an external local push force that induces stable membrane deformations and that an inward curved PM is sufficient to recruit N-BAR domains.

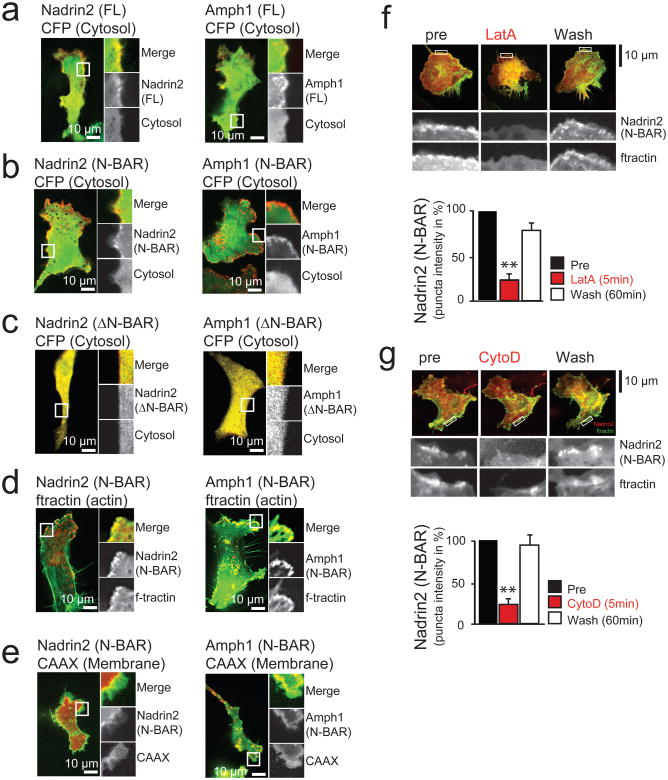

We then considered that internal forces that pull on a local membrane sites during actin reorganization or endocytosis might be equally capable in inducing the high inward curvatures necessary for N-BAR domain recruitment. We tested this hypothesis by focusing on migrating cells that experience significant membrane deformation at the leading edge15. As shown in Fig. 3a, the PM-localized N-BAR domain proteins Nadrin2 and Amphiphysin1 were enriched in the actin-rich front of polarized migrating 3T3 cells. This localization only required the N-BAR domain, since the same polarized localization was observed for full length and isolated N-BAR domains of Nadrin2 and Amphiphysin1 (Fig. 3b). Deletion of the amphipatic helix, a sequence motif required for binding and stabilization of curved membranes7,16-17, prevented enrichment of the N-BAR domain protein, arguing that localization critically depends on this structural feature required for membrane binding and present in all N-BAR domain proteins (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3. N-BAR domains are dynamically recruited to local membrane sites at the leading edge of migrating 3T3 cells.

(a) The proteins Nadrin2 and Amphiphysin1 are enriched in the leading edge of migrating 3T3 cells. (b) Enrichment in the leading edge is dependent on the N-BAR domain. Cells expressing a cytosolic marker (CFP, green) and the isolated N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 (left, red) and Amphiphysin1 (right, red). Note the polarized localization of the isolated N-BAR domain to the leading edge. (c) Enrichment in the leading edge is dependent on the amphipatic helix. Cells expressing a cytosolic marker (CFP, green) and the isolated N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 (left, red) and Amphiphysin1 (right, red) that is lacking the amino-terminal amphipatic helix show no polarized localization to the leading edge. (d) N-BAR domain patches show significant overlap with marker for filamentous actin. 3T3 cells were transfected with a marker for filamentous actin (f-tractin, green) and the N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 (left, red) or Amphiphysin1 (right, red), respectively. (e) N-BAR domain and a PM marker only partially overlap. 3T3 cells transfected with a membrane marker (CAAX, green) and the N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 (left, red) and Amphiphysin1 (right, red) are shown. (f) Addition of the actin polymerization inhibitor LatA reversibly inhibits N-BAR domain puncta formation. 1303 individual puncta from 12 cells were analyzed for the drug washout experiments. (g) Addition of the actin polymerization inhibitor CytoD reversibly inhibits N-BAR domain puncta formation. 428 puncta from 8 cells were analyzed for the drug washout experiments. Scale bars (a-g), 10μm. Error bars represent s.e.m. of the mean value. ** P < 0.01.

We observed an overlap between membrane regions with high cortical actin and either Nadrin2 or Amphiphysin1 N-BAR domains, suggesting that curved membrane sites are created above cortical actin networks (Fig. 3d). Control experiments with markers for the cytoplasm and the PM showed that this partial co-localization of N-BAR domains with cortical actin was not caused by variability in cell thickness or membrane accumulation (Figs. 3a, b and e). Furthermore, the N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 did not co-localize with a marker for Clathrin-mediated endocytosis at the leading edge (Supplementary Fig. S2h). However, we observed transient co-localization with Clathrin puncta behind the leading edge, suggestive of temporary recruitment of the isolated N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 to these internal sites during endocytosis8,18, (Supplementary Fig. S2i). Together, this argued that N-BAR domain proteins are recruited to the actin-rich leading edge membrane in a process that does not involve endocytosis and can be mediated by their N-BAR domains alone.

To more directly test the effect of peripheral actin polymerization on the localization of N-BAR domains in the front, we transiently changed actin dynamics in live cells. First, we monitored N-BAR domain puncta at the leading edge of 3T3 cells upon depolymerization of actin filaments. N-BAR domain puncta disappeared within less than 5 minutes after addition of 4μM Latrunculin A (Fig. 3f) or 5μM Cytochalasin D (Fig. 3g) and reappeared once the drug was washed out. In a complementary experiment, we rapidly triggered actin polymerization taking advantage of an assay based on inducible translocation of TIAM1, an exchange factor for Rac19. 3T3 cells were co-transfected with a fluorescently tagged N-BAR domain together with a construct containing FKBP fused to TIAM1 and a membrane-anchored FRB domain. Addition of rapamycin triggered dimerization of FRB and FKBP, rapidly recruiting TIAM1 to the PM, and causing the activation of the small GTPase Rac1. This led to increased levels of Rac-GTP at the PM causing extensive actin polymerizations and, with a delay, the translocation of the isolated N-BAR domain to the PM (Supplementary Fig. S3). A comparable result was observed when a photoactivatible version of the small GTPase Rac1 (LOV-Rac120) was used to trigger actin polymerization (Supplementary Fig. S4). Together, these experiments argue that increases in dynamic cortical actin polymerization result, with a delay, in the recruitment of curvature-sensing N-BAR domain proteins.

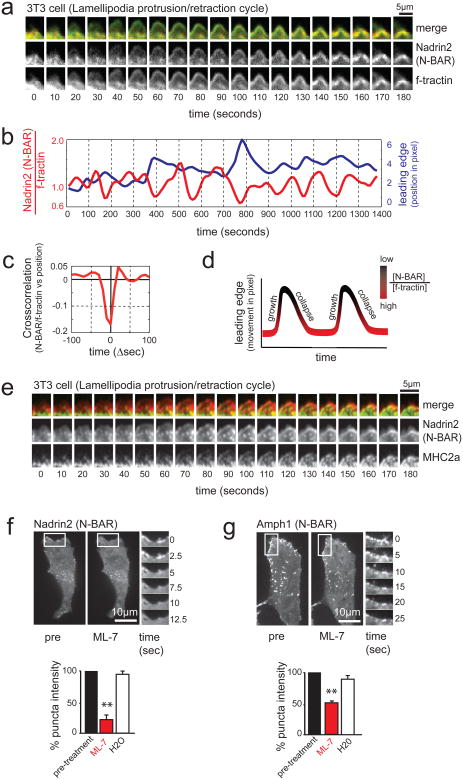

Cortical actin polymerization often occurs in cycles where a polymerization phase that extends the lamellipodia outward is followed by a retraction phase whereby the actin motor Myosin II pulls lamellipodia partially back before the next extension21-23. Markedly, time lapse imaging of cyclic lamellipodia in the front of polarized 3T3 cells showed that N-BAR recruitment occurs primarily during the retraction phase rather than the extension/polymerization phase (Fig. 4a). A time-course analysis over multiple expansion-retraction cycles showed that the concentration of the N-BAR domain (normalized to the total amount of actin filaments) remained low as the lamellipodia moved outward and only increased as it was retracted (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Movie S1). This observation was confirmed using an autocorrelation analysis comparing normalized N-BAR domain concentration and lamellipodia position (Fig. 4c, d). This cyclic nature of N-BAR domain recruitment during extension and retraction is schematically shown in Fig. 4d.

Figure 4. MyosinII-dependent contraction of actin cables induces N-BAR domain recruitment to the lamellipodia PM.

(a) N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 recruits to contracting lamellipodia. Montage depicting expansion/collapse cycle in 3T3 cells lamellipodia. Merged image of N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 (red) and f-tractin (green) at an interval of 10 seconds are shown in the top row. For clarification, separate channels of the fluorescently tagged N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 (middle row) and f-tractin (bottom row) are shown below. Note the delayed accumulation of Nadrin2 during the retractive phase of lamellipodia. (b) Comparison of normalized N-BAR domain intensity during expansion/collapse cycle of the lamellipodia. Correlation of the N-BAR domain concentration normalized to f-tractin (red) and lamellipodia position (blue) are show for an individual position on the leading edge monitored over an interval of 1400 seconds. (c) Fluorescent level of N-BAR domain (after normalization to f-tractin intensity) anti-correlate with expansion of the leading edge. Graph depicting average cross-correlation of normalized N-BAR concentration at the leading edge with the position of the leading edge over time. (d) Model of the normalized N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 concentration as a function of the leading edge position. (e) MHC2a and the N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 both enrich during lamellipodia retraction, N-BAR close to the front and MyosinII a bit further back. Montage of a 3T3 cell expressing Nadrin2 (red) and MHC2a (green) shows accumulation of both proteins during lamella retraction. (f, g) Inhibition of MyosinII causes rapid disassembly of N-BAR domain puncta at the leading edge of 3T3 cells. Addition of the MLCK inhibitor ML-7 triggers rapid disassembly of the N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 (f, red, n=8 cells) and Amphiphysin1 (g, red, n=12 cells) puncta, respectively. In contrast, no effect was visible upon addition of water (white, n=6 cells). For better visualization, a montage of a magnified section is depicted next to the pictures. Scale bars (a, e), 5 μm; (f, g), 10 μm. Error bars represent s.e.m. of the mean value, ** P < 0.01.

We hypothesized that Myosin II-mediated lamellipodia retraction involves pulling forces applied to the PM via membrane-anchored actin cables that cause local inward membrane curvature while the distributed surrounding actin meshwork resists the retraction. Consistent with such a role of Myosin II, we observed during lamellipodia retraction a parallel increase of the N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 at the front and of the heavy chain of non-muscle Myosin II (MHC2a) in a region closely behind where the lamellipodia transitions into the lamella (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Movie S2). To further validate the hypothesis that Myosin II may pull on actin cables to promote retraction, we used ML-7, an inhibitor of Myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) that controls Myosin II activity of non-muscle cells. Consistent with a key role of MLCK and Myosin II in the process of N-BAR domain recruitment, the patches of the respective N-BAR domains of Nadrin2 and Amphiphysin1 rapidly disappeared upon addition of the inhibitor (Fig. 4f, g).

This suggested that Myosin II-mediate force on actin cables induces local inward deformations of the PM at sites where the cables contact the leading edge PM. We used electron microscopy24 to analyze the topography of the PM of migrating cells and observed significant inward curved sections along the leading edge (Fig. 5a). Actin cables oriented perpendicular to the PM often pointed to the inward curved section of the PM (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. S5a), suggesting that force applied to these actin cables was responsible for the deformation. Furthermore, immune gold localization showed that the isolated N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 locally enriched at these inward curved membrane sites (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. S5b). Together, these findings introduce a recruitment mechanism whereby MLCK and Myosin II-mediated actin-contraction pulls on local PM-actin cable contact sites to create local inward curved membrane sites that then recruit N-BAR domain proteins. Notably, N-BAR puncta disappeared when PM tension was increased by lowering the external osmotic strength (Supplementary Fig. S5c). Correspondingly, lowering membrane tension with high osmotic pressure or the surface relaxant Deoxycholate25 both triggered puncta formation (Supplementary Figs. S5d, e), suggesting that N-BAR recruitment can further be regulated by changes in the global PM tension parameter.

Figure 5. External push and internal pull forces applied to local PM sites recruit N-BAR domains to inward curved membrane.

(a) Scanning Electron micrographs depicting membrane deformation at the leading edge. For better visualization, a magnification of a selected region (white box, bottom) depicting a lamellipodium is shown (top). (b) TEM of 3T3 cell parallel to the glass plane indicating actin filaments pulling at the PM as a source of plasma deformation. For better visualization the ends of individual actin cables are highlighted in red. (c) N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 accumulates on membrane deformations at the leading edge. 3T3 cells were transfected with fluorescently tagged N-BAR domain of Nadrin2, fixed and incubated with primary antibody directed against the fluorescent tag. Enrichment of Immunogold particles to curved sites was measured (n= 15 cells) and compared to adjacent regions within the same image. Note that gold-conjugated secondary antibody is significantly enriched on inward curved membrane sites (graph, bottom). (d) Different types of force-dependent membrane deformations recruit N-BAR domain proteins. N-BAR domain proteins (red) sense positive (inward) membrane curvature induced by external force such as the Nanocone substrate (left), during MyosinII triggered actin contraction (middle), and during endocytosis (right). Error bars represent s.e.m. of the mean value; ** P < 0.01.

Our results argue that different modes of mechanical deformation of the PM exist that trigger the recruitment of N-BAR domain containing regulatory proteins. First, the ability of external Nanocones to directly trigger N-BAR domain recruitment suggests that a receptor-independent mechanical signaling mechanism may exist whereby extracellular matrix components of sufficient stiffness can trigger local deformations of the PM to directly recruit and activate intracellular signaling proteins with N-BAR domains (Fig. 5d, left). Second, our results with actin and Myosin II argued that internal force applied to membrane connected actin cables can exert sufficient pull force to curve the PM and cause N-BAR domain recruitment (Fig. 5d, middle), a finding that has broad implications in actin-dependent processes such as cell polarization and migration. Third, our results also likely applies to endocytosis where Clathrin coats may provide the force that recruits N-BAR domains by creating a neck with a curved membrane tube that connects the forming Clathrin vesicle to the rest of the PM8 (Fig. 5, right). While these different recruitment mechanisms argue that local force application and induction of membrane curvature are needed to trigger the initial N-BAR domain recruitment in live cells, we would like to note that it is likely that N-BAR domains, once recruited, have a complementary role in stabilizing the curved membrane section.

In summary, our study shows that cytosolic N-BAR domains continuously scan the PM for highly inward curved sections and accumulate at sites where the membrane is sufficiently deformed by local forces. Our study further suggests that any type of push force applied to local PM sites from the outside or pull force applied to local sites from the inside will induce N-BAR domain recruitment as long as the local force is sufficiently strong and is counteracted by distributed forces on the membrane in the opposing direction. Finally, different force generating mechanism involving Clathrin, microtubules, actin cables or extracellular matrix may create in different contexts either inward (positive) or outward (negative) curved PM that likely provide only two types of distinct recruitment signals. To gain specificity, additional co-regulatory mechanisms are likely needed to link specific mechanical deformations to distinct signaling pathways and cell functions.

Methods

Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/naturecellbiology.

Supplementary Material

Movie S1 Recruitment of the curvature-sensor Nadrin2 to the leading edge of migrating 3T3 cells. 3T3 cells transfected with the isolated N-BAR domain of Nadrin (red) and the actin marker f-tractin (green) are shown. Interval between frames is 10 seconds. Playback rate is 25 frames per seconds. Scale bar is 10μm.

Movie S2 3D reconstruction of 3T3 lamella with actin (blue), N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 (red) and MHC2a (green). Playback rate is 25 frames per seconds. Scale bar is 1 μm.

Movie S3 Recruitment of the N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 (red) and MHC2a (green) to the retracting lamella in 3T3 cells. Interval between frames is 10 seconds. Playback rate is 10 frames per seconds. Scale bar is 1 μm.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the Meyer lab for comments and discussion. M.G. was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation (No. PBBSP3-123159), Novartis Jubilaeumsstiftung and Stanford Deans Postdoctoral Fellowship. S.J. was supported by the Korea Foundation for Advanced Studies graduate fellowship. Y.C. acknowledges the partial support from a DOE-EFRC at Stanford: Center on Nanostructuring for Efficient Energy Conversion (No. DE-SC0001060). T.M. acknowledges funding from the National Institute of Health, MH064801, MH095087 and GM063702.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: M.G. performed all experiments and analyzed the data. FC T. developed the temporal cross-correlation analysis. S.J. and Y.C. designed the Nanocones. LM J helped with the SEM. YI W and KM H developed the PA-Rac construct. M.G. and T.M. designed the experiments, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed results and manuscript. T.M. supervised the study.

Competing Financial Interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Habermann B. The BAR-domain family of proteins: a case of bending and binding? EMBO Rep. 2004;5:250–255. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.74001057400105[pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suetsugu S, Toyooka K, Senju Y. Subcellular membrane curvature mediated by the BAR domain superfamily proteins. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:340–349. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.12.002. S1084-9521 (09)00247-X [pii] 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rollason R, Korolchuk V, Hamilton C, Jepson M, Banting G. A CD317/tetherin-RICH2 complex plays a critical role in the organization of the subapical actin cytoskeleton in polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:721–736. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200804154. jcb.200804154 [pii] 10.1083/jcb.200804154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David C, McPherson PS, Mundigl O, de Camilli P. A role of amphiphysin in synaptic vesicle endocytosis suggested by its binding to dynamin in nerve terminals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:331–335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ringstad N, et al. Endophilin/SH3p4 is required for the transition from early to late stages in clathrin-mediated synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Neuron. 1999;24:143–154. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80828-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatia VK, et al. Amphipathic motifs in BAR domains are essential for membrane curvature sensing. Embo J. 2009;28:3303–3314. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peter BJ, et al. BAR domains as sensors of membrane curvature: the amphiphysin BAR structure. Science. 2004;303:495–499. doi: 10.1126/science.1092586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor MJ, Perrais D, Merrifield CJ. A high precision survey of the molecular dynamics of mammalian clathrin-mediated endocytosis. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamada H, et al. Dynamic interaction of amphiphysin with N-WASP regulates actin assembly. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34244–34256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yarar D, Waterman-Storer CM, Schmid SL. SNX9 couples actin assembly to phosphoinositide signals and is required for membrane remodeling during endocytosis. Dev Cell. 2007;13:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rocca DL, Martin S, Jenkins EL, Hanley JG. Inhibition of Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization by PICK1 regulates neuronal morphology and AMPA receptor endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:259–271. doi: 10.1038/ncb1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salazar MA, et al. Tuba, a novel protein containing bin/amphiphysin/Rvs and Dbl homology domains, links dynamin to regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49031–49043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richnau N, Aspenstrom P. Rich, a rho GTPase-activating protein domain-containing protein involved in signaling by Cdc42 and Rac1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35060–35070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103540200M103540200[pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeong S, McDowell MT, Cui Y. Low-Temperature Self-Catalytic Growth of Tin Oxide Nanocones over Large Areas. ACS Nano. 2011;5:5800–5807. doi: 10.1021/nn2015216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giannone G, et al. Periodic lamellipodial contractions correlate with rearward actin waves. Cell. 2004;116:431–443. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00058-3. S0092867404000583 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallop JL, et al. Mechanism of endophilin N-BAR domain-mediated membrane curvature. EMBO J. 2006;25:2898–2910. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601174. 7601174 [pii] 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masuda M, et al. Endophilin BAR domain drives membrane curvature by two newly identified structure-based mechanisms. EMBO J. 2006;25:2889–2897. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601176. 7601176 [pii] 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferguson SM, et al. Coordinated actions of actin and BAR proteins upstream of dynamin at endocytic clathrin-coated pits. Dev Cell. 2009;17:811–822. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.11.005. S1534-5807(09)00479-1 [pii] 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue T, Meyer T. Synthetic activation of endogenous PI3K and Rac identifies an AND-gate switch for cell polarization and migration. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu YI, et al. A genetically encoded photoactivatable Rac controls the motility of living cells. Nature. 2009;461:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature08241. nature08241 [pii] 10.1038/nature08241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burnette DT, et al. A role for actin arcs in the leading-edge advance of migrating cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:371–381. doi: 10.1038/ncb2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Machacek M, et al. Coordination of Rho GTPase activities during cell protrusion. Nature. 2009;461:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature08242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giannone G, et al. Lamellipodial actin mechanically links myosin activity with adhesion-site formation. Cell. 2007;128:561–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abercrombie M, Heaysman JE, Pegrum SM. The locomotion of fibroblasts in culture. IV. Electron microscopy of the leading lamella. Exp Cell Res. 1971;67:359–367. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(71)90420-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raucher D, Sheetz MP. Cell spreading and lamellipodial extension rate is regulated by membrane tension. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:127–136. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.1.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimada A, et al. Curved EFC/F-BAR-domain dimers are joined end to end into a filament for membrane invagination in endocytosis. Cell. 2007;129:761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.040. S0092-8674(07)00456-4 [pii] 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henne WM, et al. Structure and analysis of FCHo2 F-BAR domain: a dimerizing and membrane recruitment module that effects membrane curvature. Structure. 2007;15:839–852. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.05.002. S0969-2126(07)00181-5 [pii] 10.1016/j.str.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Millard TH, et al. Structural basis of filopodia formation induced by the IRSp53/MIM homology domain of human IRSp53. EMBO J. 2005;24:240–250. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600535. 7600535 [pii] 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson HW, Schell MJ. Neuronal IP3 3-kinase is an F-actin-bundling protein: role in dendritic targeting and regulation of spine morphology. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:5166–5180. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-01-0083. E09-01-0083 [pii] 10.1091/mbc.E09-01-0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riedl J, et al. Lifeact: a versatile marker to visualize F-actin. Nature methods. 2008;5:605–607. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1220. nmeth.1220 [pii] 10.1038/nmeth.1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inoue T, Heo WD, Grimley JS, Wandless TJ, Meyer T. An inducible translocation strategy to rapidly activate and inhibit small GTPase signaling pathways. Nat Methods. 2005;2:415–418. doi: 10.1038/nmeth763. nmeth763 [pii] 10.1038/nmeth763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei Q, Adelstein RS. Conditional expression of a truncated fragment of nonmuscle myosin II-A alters cell shape but not cytokinesis in HeLa cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3617–3627. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsai FC, Meyer T. Ca(2+) Pulses Control Local Cycles of Lamellipodia Retraction and Adhesion along the Front of Migrating Cells. Curr Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.037. S0960-9822(12)00324-7 [pii] 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movie S1 Recruitment of the curvature-sensor Nadrin2 to the leading edge of migrating 3T3 cells. 3T3 cells transfected with the isolated N-BAR domain of Nadrin (red) and the actin marker f-tractin (green) are shown. Interval between frames is 10 seconds. Playback rate is 25 frames per seconds. Scale bar is 10μm.

Movie S2 3D reconstruction of 3T3 lamella with actin (blue), N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 (red) and MHC2a (green). Playback rate is 25 frames per seconds. Scale bar is 1 μm.

Movie S3 Recruitment of the N-BAR domain of Nadrin2 (red) and MHC2a (green) to the retracting lamella in 3T3 cells. Interval between frames is 10 seconds. Playback rate is 10 frames per seconds. Scale bar is 1 μm.