Abstract

Objectives. We assessed whether geographic information available at the time of asthma admission predicts time to reutilization (readmission or emergency department revisit).

Methods. For a prospective cohort of children hospitalized with asthma in 2008 and 2009 in Cincinnati, Ohio, we constructed a geographic social risk index from geocoded home addresses linked to census tract extreme poverty and high school graduation rates and median home values. We examined geographic risk associations with reutilization and caregiver report of hardship.

Results. Thirty-nine percent of patients reutilized within 12 months. Compared with those in the lowest geographic risk stratum, those at medium and high risk had 1.3 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.9, 1.9) and 1.8 (95% CI = 1.4, 2.4) the risk of reutilization, respectively. Caregivers of children at highest geographic risk were 5 times as likely to report more than 2 financial hardships (P < .001) and 3 times as likely to report psychological distress (P = .001).

Conclusions. A geographic social risk index may help identify asthmatic children likely to return to the hospital. Targeting social risk assessments and interventions through geographic information may help to improve outcomes and reduce disparities.

Asthma morbidity and acute health service utilization vary geographically.1–7 Neighborhood characteristics, including socioeconomic status, have been shown to be strongly associated with asthma morbidity.3,4,7–10 Studies demonstrate that area-based, or geographic, socioeconomic characteristics approximate individual-level characteristics.11,12 Such measures are used to illustrate and monitor socioeconomic inequalities and demonstrate strong gradients for multiple health outcomes.13–16 The use of geographic data to understand population-level rates of disease is a powerful tool, but to our knowledge, such information has not been used to inform care at the individual level.

Individual-level differences in socioeconomic status are strongly associated with disparate outcomes in pediatric asthma morbidity.5,17,18 Still, clinical care guidelines do little to identify and mitigate underlying social and economic risks.19 Early identification of children at increased risk could allow for more effective targeting of resources prior to discharge. Efficiently targeting scarce hospital and community resources is increasingly important as clinicians seek to reduce acute health service utilization without increasing costs or lengths of stay.20

We assessed a novel and efficient way to stratify children with asthma at the time of admission to identify those at highest risk of further morbidity. Specifically, we examined whether area-based socioeconomic measures could be used to identify children at highest risk for further asthma-related utilization (readmission or return to the emergency department [ED]). We also assessed whether risk level derived from geographic data was associated with actual household-level financial hardships and caregiver psychological distress, factors that are associated with asthma morbidity and potentially amenable to intervention.5,21,22

METHODS

We conducted a secondary analysis of a prospective, observational cohort at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, a large, urban, academic stand-alone pediatric facility. We analyzed data from 601 patients, aged 1 to 16 years, who were enrolled between April 2008 and May 2009 after admission for asthma or wheezing. We identified patients by admission diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification 493.xx)23 and the evidence-based clinical pathway for acute asthma care by the admitting physician. The pathway includes orders for medications, delivery devices, education, and the standardized bronchodilator-weaning protocol used by respiratory therapists. Quality assurance data show the order set is used for more than 98% of all children admitted with asthma. We excluded patients who were removed from the asthma pathway after further diagnostic consideration by the attending physician. Other exclusion criteria included diagnosis of cystic fibrosis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, or congenital heart defect; having a caregiver who could not consent or participate in written or oral English; and home address outside of the hospital’s 8-county primary service area.

We enrolled 60% of eligible children who were admitted on days staffed by research personnel. Among the remainder, 11% declined participation, and 29% did not have caregivers present or staff able to complete the consent or survey process.

The primary outcome was time to first asthma-related hospital readmission or return to the ED. This was captured by classification codes of primary or secondary discharge diagnoses recorded in hospital billing data (493.xx); we hand reviewed 10% of charts to validate data accuracy (κ = 1.0). We calculated time to reutilization as the interval between the index admission and the first asthma-related hospital readmission or ED revisit. Censoring occurred at the end of the follow-up period (June 2010).

Predictors

Potential predictors were area-based socioeconomic measures that could be available at the time of hospital registration. To obtain such measures, we hired an outside firm to geocode addresses. The firm geocoded all 601 addresses with certainty to identify the census tract in which the patient lived. The 2000 US Census Bureau Summary Tape File 3 provides detailed population and housing information at the census tract level.24 Census tract socioeconomic characteristics have been conceptualized as both proxies for individual characteristics and descriptions of contextual factors. They have shown population-level gradients in health outcomes such as prematurity and lead poisoning.14,15,25

We chose 10 socioeconomic census tract variables for accessibility and availability within the public record and from a review of previous work.14,15,25–29 We used measures of poverty, ownership (home and car), housing (vacancy, value, and crowding), marriage, and education (Table 1). We dichotomized each variable at the national median value to improve generalizability to other cohorts from different geographic regions. We compared those living in census tracts above the median with those living below it.24

TABLE 1—

Risk of Reutilization (Readmission to Hospital or Emergency Department Revisit) by Geographic Socioeconomic Measures Among Children Hospitalized for Asthma: Greater Cincinnati, OH, 2008–2009

| Census Variable | Operational Definition | National Median Cutpoint,a % or $ | HRb (95% CI) |

| Poverty | |||

| 50% | Percentage of persons at < 50% of poverty line | 3.3 | 1.65 (1.30, 2.09) |

| 100% | Percentage of persons at < 100% of poverty line | 10.0 | 1.60 (1.27, 2.01) |

| Income | Median household income in 1999 | 39 882 | 1.40 (1.10, 1.77) |

| Ownership | |||

| Home | Percentage of persons who rent their home | 28.2 | 1.43 (1.12, 1.82) |

| Car | Percentage of persons who do not own a car | 6.7 | 1.39 (1.08, 1.77) |

| Housing | |||

| Vacancy | Percentage of housing units that are unoccupied | 6.1 | 1.31 (1.04, 1.65) |

| Value | Median value of owner-occupied housing units | 106 700 | 1.46 (1.14, 1.88) |

| Crowding | Percentage of households with ≥ 1 person/room | 3.2 | 1.24 (0.98, 1.57) |

| Marriage | Percentage of persons aged ≥ 25 y who have never married | 24.6 | 1.57 (1.21, 2.03) |

| Education | Percentage of persons aged ≥ 25 y with < 12th- grade education | 17.8 | 1.44 (1.15, 1.82) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio.

National median calculated for the 65 443 census tracts within the United States.

Obtained by Cox proportional hazards regression; referent group was participants living on the low-risk side of the national median.

We obtained patient demographic variables and household risks from a face-to-face survey with each patient’s caregiver. We used 5 questions, validated in national surveys, to describe family-level financial hardships (Table 2).30–33 The material and home environmental risks they predict have been linked to asthma morbidity.5,21 We also selected these hardships because patients and families experiencing them might benefit from specific clinical interventions (e.g., social work consultation, connection to pertinent community resources) if identified by the inpatient care team. Because they formed a potential criterion for referral to social work, we analyzed responses to the questions as a single dichotomous variable, assessing those reporting 2 or more hardships and those reporting fewer than 2 hardships. A sensitivity analysis assessed those reporting 1 or more hardship.

TABLE 2—

Baseline Characteristics of Sample of Children Hospitalized for Asthma: Greater Cincinnati, OH, 2008–2009

| Characteristic | Mean ±SD or No. (%) |

| Age, y | 5.9 ±4.0 |

| Male gender | 385 (64.1) |

| Race | |

| White | 234 (38.9) |

| Black | 317 (52.8) |

| Other | 50 (8.3) |

| Health insurance | |

| Private | 232 (38.6) |

| Public | 366 (60.9) |

| Self-pay | 25 (4.2) |

| Reutilizationa | 237 (39.4) |

| Family financial strain | |

| Not enough money to make ends meet | 225 (37.5) |

| Not enough food to eat | 68 (11.3) |

| Not able to pay full rent/mortgage | 137 (22.8) |

| Not able to pay full utilities | 234 (39.0) |

| Forced to move in with others for financial reasons | 80 (13.3) |

| Financial hardshipb | |

| ≥ 1 | 325 (54.1) |

| ≥ 2 | 192 (32.0) |

| Caregiver at increased risk for psychological distressc | 91 (15.1) |

Readmission to hospital or emergency department revisit within 12 months of index admission.

Positive answers, out of 5 questions.

Score on Kessler 6 scale ≥ 10; possible score = 0–24.

During the face-to-face survey, we assessed caregiver risk of psychological distress with the Kessler 6 scale, a short screening scale validated in several national surveys that assesses whether a respondent has felt, over the preceding 30 days, nervous, hopeless, restless or fidgety, depressed, that everything was an effort, or worthless.34 Each item is scored from 0 to 4 points on a Likert-based scale. Items are summed to yield a 0 to 24 score, with higher scores indicating an increased risk of psychological distress. We analyzed the Kessler 6 score as a dichotomous variable split at 10, a cutpoint that has been shown previously to effectively balance the scale’s sensitivity and specificity for detection of depression.35

Statistical Analyses

We assessed bivariate associations between each geographic variable and time to first reutilization by Cox proportional hazards regression, with the proportional hazards assumption verified with Schoenfeld residuals. We kept variables meeting statistical significance (P < .05) for further analysis. We then ranked each remaining variable in order of effect size. We identified correlations between variables with the Pearson correlation coefficient. If 2 variables were highly correlated (a priori cutoff of r > 0.60), we retained the variable with the larger effect size. Therefore, all variables remaining had correlation coefficients less than 0.60 with one another. With the goal of a useful clinical tool, we constructed a geographic social risk index from the remaining geographic variables. We gave each geographic risk identified 1 point and calculated a simple sum. To simulate a tool that could be easily used in the inpatient setting, we stratified the index into 3 risk groups. We determined cutpoints by reviewing Kaplan–Meier curves at each risk level.

We assessed the association between the geographic index and time to reutilization with the log-rank test and Cox proportional hazards regression to adjust for covariates (race, age, gender, and insurance). We assessed associations between the index and household-level factors by logistic regression.

Because racial disparities in asthma are frequently noted, we assessed the degree to which geographic factors explained the effect of race by comparing changes in the parameter estimates from different sets of Cox models (models with just caregiver-reported race and models with race, geographic index, and other covariates).36 We also assessed changes in the parameter estimates for those at high geographic risk after adjustment for additional covariates.

We performed all analyses with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Because participants might have clustered within census tracts, we applied the survey type of Cox proportional hazards modeling with the surveyphreg procedure. We captured face-to-face data with Research Electronic Data Capture, a secure, Web-based application.37

RESULTS

Our sample was 64% male, 53% Black, and 61% publicly insured, and the mean age was 5.9 years (Table 2). Seventy-two percent of the sample had an address in Hamilton County, the site of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Of the 601 children enrolled, 237 (39.4%) were readmitted or returned to the ED within 12 months. Approximately one third of caregivers reported 2 or more financial hardships, and 15.1% scored at risk for psychological distress. Enrolled and eligible but unenrolled children did not differ in age, gender, race, insurance, or likelihood of reutilization.

Patients in the sample came from 286 census tracts (1–12 patients/tract). The socioeconomic characteristics of these census tracts varied. For example, some children were from census tracts where fewer than 1% of individuals lived in extreme poverty; others lived in census tracts where more than 50% lived in extreme poverty (range = 0.3%–52.6%).

Geography and Reutilization

Nine of the 10 dichotomized geographic variables were significantly associated with time to reutilization (Table 1). For example, compared with individuals living in census tracts where the extreme poverty rate was below the national median (3.3%), individuals living in census tracts above the national median had a 65% increased risk of reutilization (P < .001). Similarly, compared with individuals living in census tracts where the median home value was above the national median ($106 700), individuals living in census tracts below the national median had a 46% increased risk of reutilization (P = .003). Finally, compared with those living in census tracts where the rate of adults without a high school education was below the national median (17.8%), individuals living in census tracts with rates above the national median had a 44% increased risk of reutilization (P = .002).

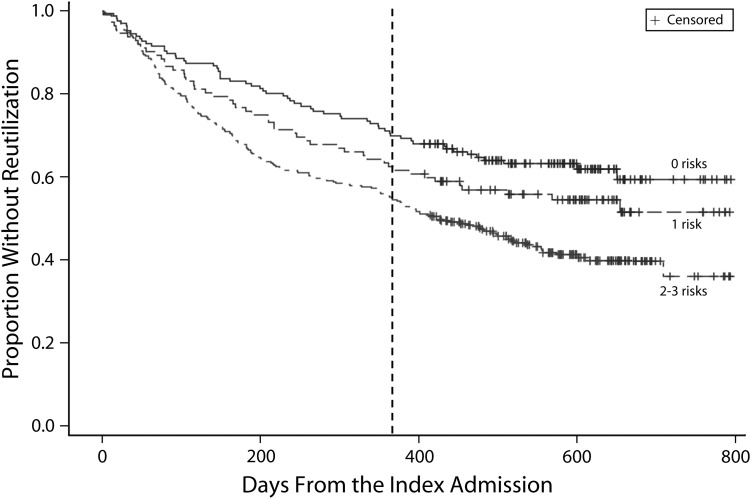

The geographic index incorporated census tract extreme poverty rate, median home value, and rate of adults who had not received a high school or equivalent degree. We based our selection of these variables on effect size and our correlation analysis. We assigned 1 point if a child lived in a census tract in which the extreme poverty rate was above the national median, the median home value was below the national median, or the rate of adults with less than a high school degree was above the national median (total score range = 0–3). Because the Kaplan–Meier curves for participants with 2 and 3 risks were very close, we stratified the index into 3 risk groups: low (0 risks), medium (1 risk), and high (2–3 risks). Roughly 27% of children were classified as low, 19% as medium, and 54% as high risk.

The unadjusted geographic index was associated with time to reutilization in a graded fashion (Figure 1). At 12 months following index admission, 30% of those at low, 38% at medium, and 45% at high risk had reutilized (P = .006). Children at medium geographic risk had a 1.30 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.90, 1.88) and children at high geographic risk had a 1.83 (95% CI = 1.37, 2.44) likelihood of reutilization relative to children at low risk (Table 2). We observed a similar graded effect for hospital readmission alone (excluding ED revisit): children at medium geographic risk had a 1.34 (95% CI = 0.83, 2.17) and children at high geographic risk had a 1.76 (95% CI = 1.20, 2.58) likelihood of readmission compared with low-risk children. Adjustment for age, gender, insurance, and clustering at the census tract level did not change effect sizes. Similarly, limiting our sample to children living in Hamilton County produced no significant change in observed effect.

FIGURE 1—

Survival curve for time to reutilization (readmission to hospital or emergency department revisit) among children hospitalized for asthma, stratified by the geographic social risk index: Greater Cincinnati, OH, 2008–2009.

Note. Index comprised census tract extreme poverty rate, rate of adults with < high school graduation, and median home value; strata significantly differed (P < .001).

Association of Geographic- and Individual-Level Risks

Children in families reporting 2 or more financial hardships were at significantly increased risk of reutilization within 12 months compared with those with fewer hardships (47% vs 36%; hazard ratio [HR] = 1.57; 95% CI = 1.24, 1.98). Families of 14% of children at low geographic risk, 29% at medium risk, and 42% at high risk had 2 or more financial hardships (P < .001). Those at medium geographic risk had a 2.49 odds ratio (OR; 95% CI = 1.36, 4.54) and those at high geographic risk had a 4.58 OR (95% CI = 2.80, 7.49) of reporting 2 or more hardships. Similarly, those at medium geographic risk had a 4.32 OR (95% CI = 2.59, 7.20) and those at high geographic risk had a 5.07 OR (95% CI = 3.36, 7.65) of reporting 1 or more hardships.

Children of caregivers at risk for psychological distress according to their Kessler 6 scores had higher rates of reutilization than did children whose caregivers had lower risk (48% vs 38%; HR = 1.45; 95% CI = 1.09, 1.93). Eight percent of caregivers in the low-risk, 14% in the medium-risk, and 20% in the high-risk geographic strata were at risk for psychological distress (P = .003). Children at medium and high geographic risk had a 1.82 OR (95% CI = 0.83, 3.99) and 2.85 OR (95% CI = 1.52, 5.35), respectively, of having caregivers at risk for psychological distress.

Black children were significantly more likely than White children to be classified as high risk according to the geographic index (73% vs 27%; P < .001). However, when we stratified patients for risk by race alone, 62 White children and 87 Black children, or 25% of the entire sample, were misclassified. Black children were more likely than White children to return to the hospital or ED (HR = 1.82; 95% CI = 1.41, 2.35). The parameter estimates for race and children at high geographic risk both decreased by 32% when incorporated into the same model (Table 3). Age, gender, and insurance, other data readily available on admission, had no significant impact on the parameter estimates for race or the index.

TABLE 3—

Adjusted Associations Between Geographic Index and Time to Reutilization (Readmission to Hospital or Emergency Department Revisit) Among Children Hospitalized for Asthma: Greater Cincinnati, OH, 2008–2009

| Geographic Risk Index | Model 1,a Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Model 2,b Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Model 3,c Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

| Low (0 risks; Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medium (1 risk) | 1.30 (0.90, 1.88) | 1.14 (0.76, 1.71) | 1.13 (0.75, 1.71) |

| High (2–3 risks) | 1.83 (1.37, 2.44) | 1.51 (1.06, 2.14) | 1.49 (1.03, 2.15) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio.

Included unadjusted geographic index.

Included index and race (32.1% decrease in parameter estimate for those at high geographic risk, compared with model 1).

Included index, race, age, gender, and insurance (34.3% decrease in parameter estimate for those at high geographic risk, compared with model 1).

DISCUSSION

Disparities in children's asthma morbidity and health care utilization remain deep and persistent. In our geographic social risk index, extreme poverty, lower home value, and fewer adults with a high school degree were strongly associated with asthma-related reutilization. Such population-level data were also strongly associated with caregiver report of financial hardship and psychological distress, both of which are linked to adverse asthma outcomes.5,21,22 Thus, the geographic index identifies a large segment of children at high risk for further morbidity and points to potential areas for family-level assessment and intervention.

Geographic Risk and Reutilization

Census tract socioeconomic variables were significantly associated with an individual’s risk of reutilization. The association between geographic risk and reutilization at the patient level was similar to previously described associations at the population level. Krieger et al. have consistently shown strong associations between area-based socioeconomic measures and health outcomes.13–16,38 Others have identified area-level hospitalization hot spots characterized by factors such as low household income and inadequate housing.39–41 Previous studies assessed at-risk areas for population-level disease and disparity surveillance. They did not, however, routinely associate them with an individual patient’s health risk prospectively.

With the aim of developing a useful clinical tool, we constructed a geographic risk index from census tract data available on admission. We stratified data into 3 risk domains and found that those at highest geographic risk were 80% more likely to reutilize than were those at lowest risk, highlighting a clinical population that may benefit from further assessments and interventions. In the hospital, this geographic risk index could be used to inform targeted patient-level solutions to prevent reutilization, especially if such data could be integrated into evolving electronic health records.42 The use of freely available geographic data might also inform preventative approaches, highlighting neighborhood hot spots that could benefit from community-based interventions.

Factors Amenable to Intervention

The association we found between the geographic index and time to reutilization may be partially explained by differences in household-level social factors linked to asthma morbidity. Our unadjusted geographic index revealed that children classified as high risk were nearly 5 times as likely as other children to have 2 or more financial hardships (as well as 5 times as likely to have ≥ 1 financial hardships), and nearly 3 times as likely to have caregivers experiencing psychological distress. Because the effect of geography is likely mediated through household- and area-level factors that affect medication adherence, trigger exposure, and physiologic manifestations of disease,5,21,22,43,44 the index has potential as a triage tool that can serve to better identify children at highest risk.

Improved ability to detect competing household priorities and toxic physical environments such as household-level financial and psychological strains could be clinically powerful. Screening with geographic data could lead to more complete and pertinent social histories and more efficient linkage to such interventions as social work consultation, case management, and use of community resources (e.g., medical–legal partnerships or mental health providers).45 After discharge, geographic data could also be integrated into the chronic asthma care plan.

Geographic Risk and Race

We conceptualized the effect of race as being explained, in part, by social and economic factors captured by the geographic data. The association between race and asthma reutilization decreased by 32% when we incorporated both factors into the same model as the geographic index.46 Although collecting data on a patient’s race or ethnicity is being encouraged for purposes of identifying disparities in health care service delivery,47 we believe its use for patient-level risk stratification and treatment is still inappropriate.48 It is difficult to justify ethically the provision of different care to one patient over another on the sole basis of racial or ethnic background. Moreover, our data suggest that classifying social risk by race alone would misclassify a significant number of children. Geographic measures of socioeconomic status may be especially useful because race is often a poor proxy for poverty, racial/ethnic diversity makes distinctions more difficult, and data on race are often not reliably or accurately collected.49,50

Adding available and accessible census data on admission allows for a more complete assessment of a patient’s social risk status, reflecting contextual markers of poverty, environmental exposures, and accessibility of resources.15 In an era of rare physician home visits, mapping geographic data to the patient could be an important first step in bringing neighborhood context back to the bedside. This virtual home visit could identify opportunities in the clinical care context to reduce disparities.

Limitations

Validation of this index with a second data set is needed. Still, we believe that the associations between the geographic index and a patient’s characteristics suggest that the index is measuring something intrinsic and provides reassurance that we are capturing something relevant at the patient level.

Although the recruitment of our sample took place in 2008 and 2009, data came from the 2000 US Census. However, population and neighborhood shifts in Greater Cincinnati since the 2000 Census have been minimal.24

Our results may be subject to the ecological fallacy. If an individual lived in a census tract characterized by poverty, we assigned an area-based value to that individual. We believe that the homogeneity of census tracts makes it a relatively robust assumption, and we tested the validity of that assumption with household-level factors.15 Still, additional, unmeasured social and environmental factors commonly associated with poverty (e.g., access to care, exposure to cockroaches, exposure to tobacco smoke) may further exacerbate a child’s symptoms and increase the risk of reutilization.51

Our sample was drawn from a single health system, so children could seek care elsewhere. Because we excluded children living outside of our primary service area, the number of children seeking care outside our system likely did not significantly affect our results. A sensitivity analysis, assessing just those children living in our institution’s home county, with even lower rates of loss to follow-up, showed no significant change in our findings.

Finally, our cohort excluded families with limited English proficiency (< 2% of admissions). Consequently, our findings may not be generalizable to asthma populations in other regions or with different demographic characteristics.

Conclusions

Geographic information available at admission predicts future asthma-related utilization. It also identifies families who are likely to report financial or psychological hardships. The use of geographic data to target social risk assessments and interventions may help inform clinical decisions and reduce disparities.

We plan to validate this geographic index in a second asthma cohort that is currently being enrolled. We also will evaluate whether environmental, crime, or other geographic data (e.g., distance to clinic or pharmacy) add useful information that could make this more a virtual neighborhood visit than just a virtual home visit. We will also assess geographic data’s associations with other asthma outcomes (e.g., intensive care unit admissions, access to primary care, medication adherence) and other conditions (e.g., diabetes mellitus). Ultimately, we plan to assess whether the introduction of geographic data into clinical care leads to more in-depth and reliable triage of patients according to future risk. Similarly, we plan to evaluate whether clinical availability of geographic socioeconomic measures facilitates efficient linkages to available hospital- or community-based interventions for those patients most likely to benefit.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Bureau of Health Professions (BHPR), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), under the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Primary Care Research Fellowship in Child and Adolescent Health (T32HP10027). Cohort recruitment and database assembly were supported by a Thrasher Research Fund New Investigator Award (to J. M. S. and R. S. K.) and a CCHMC Outcomes Research Award (to J. M. S., A. F. B., and R. S. K.). Further support came from a Robert Wood Johnson Faculty Scholars Award and the National Institutes of Health (grant 1R01AI88116 to Robert S. Kahn). Use of Research Electronic Data Capture was supported by the Center for Clinical and Translational Science and Training (grant NCRR/NIH UL1-RR026314-01).

These data were presented in abstract form at the Pediatric Academic Societies, April 30–May 3, 2011, Denver, CO, and Pediatric Hospital Medicine, July 27–31, 2012, Kansas City, MO.

We thank Stacey Rieck and Hadley Sauers (clinical research coordinators, CCHMC) for dedication to study recruitment, and data management. Patrick Conway, MD MSc, Katherine Auger, MD, Karen Jerardi, MD, and Hadley Sauers, BA, assisted with manuscript editing.

Note. The information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by the BHPR, HRSA, DHHS or the US Government.

Human Participant Protection

This study was reviewed and approved by the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center institutional review board. Informed consent of human participants was obtained.

References

- 1.Gupta RS, Zhang X, Sharp LK, Shannon JJ, Weiss KB. Geographic variability in childhood asthma prevalence in Chicago. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(3):639–645e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saha C, Riner ME, Liu G. Individual and neighborhood-level factors in predicting asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(8):759–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Claudio L, Tulton L, Doucette J, Landrigan PJ. Socioeconomic factors and asthma hospitalization rates in New York City. J Asthma. 1999;36(4):343–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu SY, Pearlman DN. Hospital readmissions for childhood asthma: the role of individual and neighborhood factors. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(1):65–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams DR, Sternthal M, Wright RJ. Social determinants: taking the social context of asthma seriously. Pediatrics. 2009;123(suppl 3):S174–S184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright RJ, Subramanian SV. Advancing a multilevel framework for epidemiologic research on asthma disparities. Chest. 2007;132(5 suppl):757S–769S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shankardass K, Jerrett M, Milam J, Richardson J, Berhane K, McConnell R. Social environment and asthma: associations with crime and No Child Left Behind programmes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(10):859–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith LA, Hatcher-Ross JL, Wertheimer R, Kahn RS. Rethinking race/ethnicity, income, and childhood asthma: racial/ethnic disparities concentrated among the very poor. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(2):109–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claudio L, Stingone JA, Godbold J. Prevalence of childhood asthma in urban communities: the impact of ethnicity and income. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(5):332–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Litonjua AA, Carey VJ, Weiss ST, Gold DR. Race, socioeconomic factors, and area of residence are associated with asthma prevalence. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999;28(6):394–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Subramanian SV, Chen JT, Rehkopf DH, Waterman PD, Krieger N. Comparing individual- and area-based socioeconomic measures for the surveillance of health disparities: a multilevel analysis of Massachusetts births, 1989–1991. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(9):823–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rehkopf DH, Haughton LT, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Subramanian SV, Krieger N. Monitoring socioeconomic disparities in death: comparing individual-level education and area-based socioeconomic measures. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2135–2138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Rehkopf DH, Subramanian SV. Painting a truer picture of US socioeconomic and racial/ethnic health inequalities: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(2):312–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Rehkopf DH, Subramanian SV. Race/ethnicity, gender, and monitoring socioeconomic gradients in health: a comparison of area-based socioeconomic measures—the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1655–1671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV, Carson R. Choosing area based socioeconomic measures to monitor social inequalities in low birth weight and childhood lead poisoning: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project (US). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(3):186–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krieger N, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV. Monitoring socioeconomic inequalities in sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, and violence: geocoding and choice of area-based socioeconomic measures—the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project (US). Public Health Rep. 2003;118(3):240–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akinbami LJ, LaFleur BJ, Schoendorf KC. Racial and income disparities in childhood asthma in the United States. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2(5):382–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ash M, Brandt S. Disparities in asthma hospitalization in Massachusetts. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(2):358–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma—Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5 suppl):S94–S138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sulman J, Savage D, Way S. Retooling social work practice for high volume, short stay. Soc Work Health Care. 2001;34(3–4):315–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright RJ. Epidemiology of stress and asthma: from constricting communities and fragile families to epigenetics. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2011;31(1):19–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weil CM, Wade SL, Bauman LJ, Lynn H, Mitchell H, Lavigne J. The relationship between psychosocial factors and asthma morbidity in inner-city children with asthma. Pediatrics. 1999;104(6):1274–1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1980. DHHS publication PHS 80-1260 [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Census Bureau. American Factfinder, decennial census. 2000; Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DatasetMainPageServlet?_program=DEC&_submenuId=datasets_0&_lang=en. Accessed May 28, 2010.

- 25.Eibner C, Sturm R. US-based indices of area-level deprivation: results from HealthCare for Communities. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(2):348–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carstairs V. Deprivation indices: their interpretation and use in relation to health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49(suppl 2):S3–S8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jarman B. Identification of underprivileged areas. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286(6379):1705–1709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Messer LC, Laraia BA, Kaufman JSet al. The development of a standardized neighborhood deprivation index. J Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1041–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh GK. Area deprivation and widening inequalities in US mortality, 1969–1998. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(7):1137–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danziger S, Corcoran M, Danziger S, Heflin CM. Work, income, and material hardship after welfare reform. J Consum Aff. 2000;34(1):6–30 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayer SE, Jencks C. Poverty and the distribution of material hardship. J Hum Resour. 1989;24(1):88–114 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Short K, Shea M. Beyond Poverty, Extended Measures of Well-Being, 1992. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 1995. Current Population Reports, P20-50RV [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ouellette T, Burstein N, Long D, Beecroft E. Measures of Material Hardship: Final Report. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJet al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baggaley RF, Ganaba R, Filippi Vet al. Detecting depression after pregnancy: the validity of the K10 and K6 in Burkina Faso. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12(10):1225–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin DY, Fleming TR, De Gruttola V. Estimating the proportion of treatment effect explained by a surrogate marker. Stat Med. 1997;16(13):1515–1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV, Carson R. Geocoding and monitoring of US socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and cancer incidence: does the choice of area-based measure and geographic level matter?: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(5):471–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corburn J, Osleeb J, Porter M. Urban asthma and the neighbourhood environment in New York City. Health Place. 2006;12(2):167–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gottlieb DJ, Beiser AS, O’Connor GT. Poverty, race, and medication use are correlates of asthma hospitalization rates. A small area analysis in Boston. Chest. 1995;108(1):28–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castro M, Schechtman KB, Halstead J, Bloomberg G. Risk factors for asthma morbidity and mortality in a large metropolitan city. J Asthma. 2001;38(8):625–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Comer KF, Grannis S, Dixon BE, Bodenhamer DJ, Wiehe SE. Incorporating geospatial capacity within clinical data systems to address social determinants of health. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(suppl 3):54–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith LA, Bokhour B, Hohman KHet al. Modifiable risk factors for suboptimal control and controller medication underuse among children with asthma. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4):760–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen E, Bloomberg GR, Fisher EB, Jr, Strunk RC. Predictors of repeat hospitalizations in children with asthma: the role of psychosocial and socioenvironmental factors. Health Psychol. 2003;22(1):12–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kenyon C, Sandel M, Silverstein M, Shakir A, Zuckerman B. Revisiting the social history for child health. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3):e734–e738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krieger N. Refiguring “race”: epidemiology, racialized biology, and biological expressions of race relations. Int J Health Serv. 2000;30(1):211–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorsey R, Graham G. New HHS data standards for race, ethnicity, sex, primary language, and disability status. JAMA. 2011;306(21):2378–2379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thorlby R, Jorgensen S, Siegel B, Ayanian JZ. How health care organizations are using data on patients’ race and ethnicity to improve quality of care. Milbank Q. 2011;89(2):226–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kawachi I, Daniels N, Robinson DE. Health disparities by race and class: why both matter. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):343–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kressin NR, Chang BH, Hendricks A, Kazis LE. Agreement between administrative data and patients’ self-reports of race/ethnicity. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1734–1739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kattan M, Mitchell H, Eggleston Pet al. Characteristics of inner-city children with asthma: the National Cooperative Inner-City Asthma Study. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1997;24(4):253–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]