Comparative effectiveness studies of medical products outside of experimental research settings often derive from secondary data sources, such as insurance claims, that include data from many geographic regions and sometimes the entire country. The large source population available through these data sources allows investigators to study uncommon outcomes or exposures. Indeed, such considerations are important for the FDA’s Sentinel Initiative, which aims to create a coordinated national electronic medical product safety surveillance system, covering 100 million patients from disparate data sources and thereby geographic regions by mid 2012. A recent publication1, however, has cast doubt on the validity of this venture, owing to potential biases arising from regional variations in medical practice intensity.

Well documented geographic variation in US health care

Research has shown a more than two-fold variation in health care utilization and in per capita Medicare spending in different regions of the US.2 Research on the causes of these differences has found that higher use and spending is due largely to the overall intensity of discretionary care provided to similar patients: how much time they spend in the hospital, how frequently they see physicians, and how many diagnostic tests and minor procedures they receive.3 That is, the variations cannot be explained by other legitimate factors that also vary across regions or hospitals, such as differences in price paid per procedure4, poverty5–7 or severity of illness6. Moreover, evidence suggests that hospitals and regions that provide more care to Medicare patients also provide more for their non-Medicare patients.8, 9 For example, a high correlation was found between Part B (physician) spending for the elderly and the rate of Cesarean sections among normal birth weight babies, suggesting the way doctors and hospitals deliver care is similar in any given region, regardless of who is paying.2

Emerging concern: Regional variation as a source of misclassification of study variables threatens the validity of comparative effectiveness research

Recently, an important concern has been raised regarding the implications of regional variation in medical practice intensity for the validity of comparative effectiveness research. Song et al1 categorized 306 US hospital referral regions into quintiles based on the end-of-life expenditure index (EoLEI) to measure intensity of medical care. The EoLEI is calculated as age-sex-race-adjusted spending (measured with standardized national prices) on hospital and physician services provided to Medicare enrollees who were in their last 6 months of life in each hospital referral regions in mid 1994 to 1997. The authors compared trends with respect to diagnoses, laboratory testing, imaging, and the assignment of Hierarchical Condition Categories (HCCs) among beneficiaries who moved, and found greater increases among beneficiaries who moved to regions with a higher intensity of practice than among those who moved to regions with the same or lower intensity of practice. These differences across the regions in diagnostic practices that were independent of patients’ underlying health status led the authors to conclude that “the use of clinical or claims-based diagnoses in risk adjustment may introduce important biases in comparative effectiveness studies”.

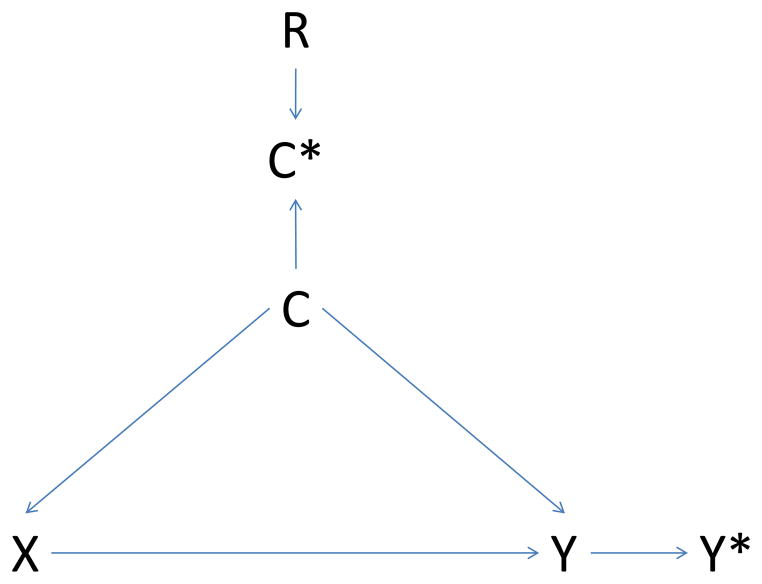

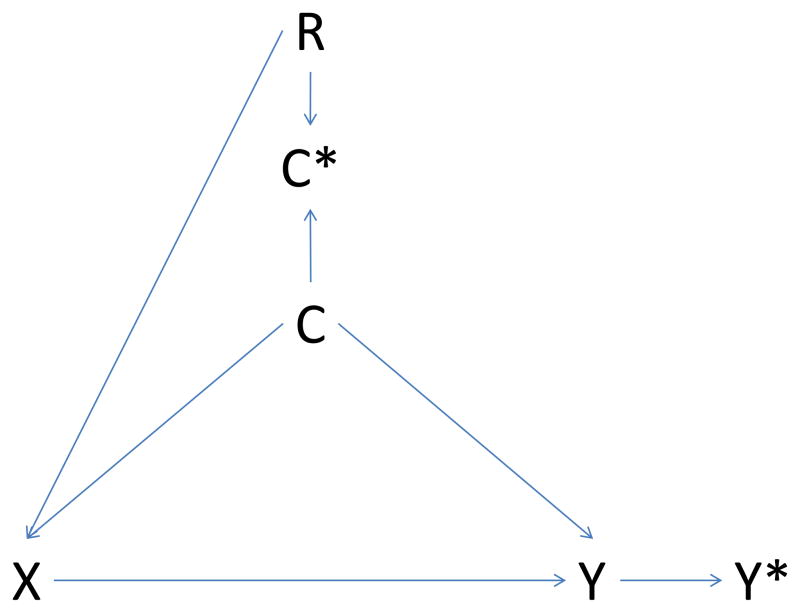

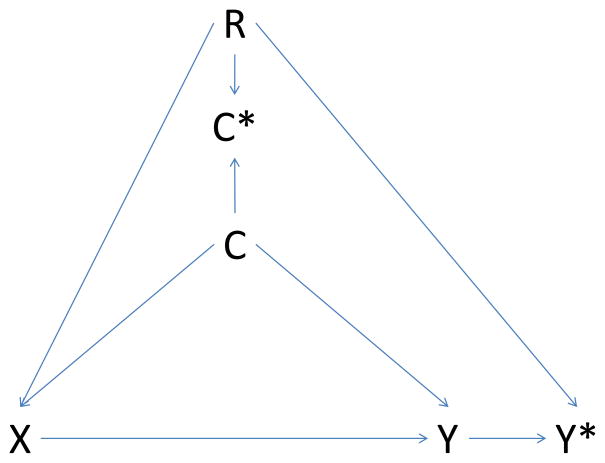

Variation in the quantity of healthcare utilization translates into variation in the opportunity to capture diagnoses in claims databases. These differences in turn result in differences in covariate ascertainment by region, thereby reducing the effectiveness of confounding control.10 The conclusion of Song et al that such misclassification will introduce a bias is only justified, however, if regions that differ on covariate ascertainment also differ with respect to presence of the study exposure (i.e., if the misclassification is differential). If that is the case, then region will have to be taken into account to remove any additional bias introduced (Figure 1). Using the terminology of causal diagrams, conditioning on region closes the backdoor path from exposure to outcome through region.11

Figure 1. Causal diagram illustrating potential bias introduced by regional variation in intensity of care.

Panel A – non-differential misclassification of confounder

Panel B – differential misclassification of confounder

Panel C – differential misclassification of confounder and outcome

X: exposure; Y: outcome; C: confounder; C*: measured confounder; Y*: measured outcome; R: region

Causal diagrams visually encode the causal relations among the exposure, outcomes, and covariates. In a causal graph, the only sources of marginal association between variables are the open paths between them. A path is a sequence traced out along connectors. A path is considered ‘open’ if there is no variable on the path where two arrowheads meet (known as a collider variable). For example, in Panel A the two open paths between exposure X and measured outcome Y* are X→Y→Y* and X→C→Y→Y*. Conditioning on the collider C* (e.g., adjustment for the measured confounder C*) opens the path at C*. Consequently, if region is associated with exposure (R → X, Panel B), and we condition on the measured confounder C*, then region may act as a confounder through the pathway X → R → C* → C → Y → Y*. If region is also associated with outcome measurement (R → Y*, Panel C), the path X → R → Y* opens as well. Conditioning on the noncollider R will block both paths

Empirical studies to examine effect of accounting for variation in medical practice intensity

To gain insight in the practical relevance of potential covariate misclassification owing to regional variation in medical practice, we evaluated three studies – one of which has previously been published12 - to see whether the conditions for bias were met and whether accounting for region using quintiles of the proposed EoLEI would alter effect estimates (implying the presence of bias). These studies derive from two different data sources each incorporating regions with different medical care intensity: (i) a population of patients ≥65 years enrolled in both Medicare and the Pennsylvania Pharmaceutical Assistance Contract for the Elderly (PACE) programs between 1995 and 2002 (Pennsylvania, Example 1); and (ii) a population of patients ≥65 years enrolled in Medicare with prescription drug coverage through either a stand-alone Part D plan or a retiree drug plan in 2005–2007 that was administered by a pharmacy benefits management company (all US states, Examples 2 and 3). All three analyses used an intent-to-treat approach with initial exposure status as determined from pharmacy claims carried forward until censoring at end of follow-up or the occurrence of the outcome of interest, whichever came first. All patients were new users, defined as not having a prescription for the medication of interest in the prior 180 days. Baseline covariates were assessed using healthcare utilization data within the 6 months before treatment initiation. Time to death was ascertained using Medicare claims, which are routinely cross-checked with Social Security data. Myocardial infarction was defined as a hospitalization ≥3 days (unless the subject died during the hospitalization) with a principal or secondary diagnosis of ICD-9-CM 410.x1. We implemented a high-dimensional propensity score (hdPS) algorithm to adjust for confounding using claims-based clinical covariate information.12, 13 Healthcare utilization or claims data indirectly describe the health status of patients through the lenses of healthcare providers operating under the constraints of a specific healthcare system. Measuring a large battery of variables should increase the likelihood that in combination they will serve as a good proxy for relevant unobserved confounding factors. The hdPS algorithm identifies thousands of diagnoses, procedures, and pharmacy claim codes, eliminates covariates of very low prevalence and minimal potential for causing confounding using well-established methods,14, 15 and then uses propensity score techniques to adjust for a large number of target covariates. These newly-identified covariates can result in better confounding adjustment and opportunity for valid causal inference than conventional approaches based solely on investigator-defined covariates.13, 16, 17 Despite these advantages, it should be noted that any systematic difference between regions in intensity of healthcare use will be transferred to the hdPS as it is estimated using diagnoses and procedures documented during and medication use resulting from actual encounters with the healthcare system.

Table 1 provides a basic description of the study populations. Both datasets include hospital referral regions with different medical care intensity. All 306 hospital referral regions are represented in the nationwide data (Examples 2 and 3), versus only 23 regions in the regional dataset (Example 1). In both of these datasets, variation in medical care intensity across regions similar to that reported by Song is seen, but the differences are less pronounced for the regional dataset. The distributions of treatments studied, however, did not differ meaningfully by region. To assess the effect of accounting for region, we mapped each patient’s zip code of residence to one of the 306 US hospital referral regions linked to a quintile of the EoLEI, and compared the exposure-outcome associations of interest (Table 2) adjusted for the hdPS with the associations adjusted for both the hdPS and EoLEI-quintiles. The respective outcome models (logistic regression for example 1 and Cox proportional hazard regression for examples 2 and 3) adjusted for deciles of the estimated hdPS were stratified by EoLEI-quintile. Within the context of these data sources and clinical scenarios, and after adjustment of confounding by claims-based clinical information, further adjustment for regional variations in healthcare intensity did not lead to meaningful changes in study results, indicating that confounder misclassification owing to regional variation in practice is not an important source of additional bias (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study populations

| Song | Regional Data (Example 1) | Nationwide Data (Examples 2 and 3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 2,931,319 | 36,106 | 221,734 |

|

| |||

| EoLEI quintiles

| |||

| Quintile 1 | |||

| Number of Hospital Referral Regions | 93 | 4 | 93 |

| % of patients | 20.5 | 10.2 | 15.2 |

| Quintile 2 | |||

| Number of Hospital Referral Regions | 60 | 6 | 60 |

| % of patients | 19.9 | 9.3 | 20.2 |

| Quintile 3 | |||

| Number of Hospital Referral Regions | 58 | 6 | 58 |

| % of patients | 20.2 | 20.4 | 20.6 |

| Quintile 4 | |||

| Number of Hospital Referral Regions | 52 | 3 | 52 |

| % of patients | 21.3 | 12.7 | 17.7 |

| Quintile 5 | |||

| Number of Hospital Referral Regions | 43 | 4 | 43 |

| % of patients | 18.1 | 47.4 | 26.4 |

|

| |||

| Demographic Characteristics

| |||

| Age, year | 75.5 | 77.7 | 74.9 |

| Female Sex, % | 61.0 | 81.8 | 59.9 |

| Black Race, % | 6.6 | 7.4 | 9.7 |

|

| |||

| Variation in intensity of medical care(1) by EoLEI-Quintile (Quintile 5/Quintile 1) | |||

|

| |||

| Doctor visits | 1.53 | 1.19 | 1.48 |

| Laboratory tests | 1.74 | 1.67 | 1.85 |

| Imaging services | 1.31 | 1.21 | 1.40 |

| Diagnoses | 1.49 | 1.12 | 1.41 |

| Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) risk score | 1.17 | 1.06 | 1.20 |

Defined as described by Song et al1

Table 2.

The impact of accounting for region on measures of association in three examples

| HR (95% CI) Adjusted for hdPS | HR (95% CI) Adjusted for hdPS and EoLEI-quintiles* | |

|---|---|---|

| Regional Medicare claims data with pharmacy assistance program data on medications | ||

| Example 1: Statin versus glaucoma drug initiators and 1-year risk of mortality | 0.89 (0.78 – 1.02)12 | 0.88 (0.79 – 1.02) |

|

| ||

| Nationwide Medicare claims data with Medicare Part D data on medications | ||

| Example 2: High- versus low-intensity statin initiators and 180-day risk of myocardial infarction or mortality | 1.01 (0.95 – 1.07) | 1.01 (0.95 – 1.07) |

| Example 3: Vytorin versus simvastatin initiators and 180-day risk of myocardial infarction | 0.92 (0.73 – 1.17) | 0.91 (0.72 – 1.16) |

EoLEI-quintile accounted for through stratification

Sensitivity analyses to explore conditions for meaningful bias

Although we examined different data sources, exposures and outcomes, the skeptical reader might question the generalizability of conclusions drawn from these three specific examples and using a particular measure of medical care intensity which is not without controversy.18 We therefore conducted sensitivity analyses to explore more generally the conditions under which regional variation in intensity of care could introduce meaningful bias, which we defined as a ≥10% change in effect estimate. We examined various scenarios defined by the strength of the associations between region, confounder, exposure and outcome. As indicated earlier, if the exposure prevalence does not differ across regions (Figure 1, Panel A), the problem described by Song et al reduces to that of non-differential misclassification of a confounder, which yields incomplete confounding adjustment.10 In this situation, additional adjustment for region does not reduce the residual confounding; instead, the effect of the confounder misclassification on the study findings could be explored using quantitative bias analyses19, or regression calibration techniques.20 If the exposure distribution differs by region but the outcome ascertainment does not (as would be expected for hard endpoints such as mortality) (Figure 1, Panel B), our sensitivity analyses indicated that extremely strong associations between region and exposure and between confounder and outcome (i.e., RR ≥6) would be required for regional variation to result in meaningful additional bias. Such strong associations are likely to be rare. If, on the other hand, outcome ascertainment also varies by region (for example, earlier diagnosis of abnormal liver function through closer monitoring of blood test values in high-intensity regions) (Figure 1, Panel C), regional variations in healthcare intensity may result in meaningful additional bias under a range of scenarios, provided the association between region and exposure is also moderately strong (i.e., RR ≥1.5). These conclusions are independent of the specific measure chosen to quantify differences in medical care intensity.

Conclusion

So what is the practical import for researchers conducting comparative effectiveness studies that include regions with differing medical care intensity, or policy makers evaluating such studies? In most instances, regional variation will be one of many potential mechanisms through which non-differential misclassification of confounders might occur. If the data indicate that exposure prevalence varies substantially across regions of different medical care intensity and sizeable differences in outcome ascertainment by region are possible, then it would be advisable to account for region in the analyses to eliminate the additional bias that might arise from this source. Nevertheless, based on the three typical example studies and our sensitivity analyses, we believe that the conditions for important bias will be rare, and the practical implications of regional variation in medical practice intensity – as a proxy for confounder misclassification - will typically be negligible.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources:

The research was supported in part by grant NHLBI RC4-HL106376, issued under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

None

References

- 1.Song Y, Skinner J, Bynum J, Sutherland J, Wennberg JE, Fisher ES. Regional variations in diagnostic practices. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:45–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0910881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skinner J, Fisher E. Reflections on Geographic Variation in US Health Care. 2010 (available at http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/press/Skinner_Fisher_DA_05_10.pdf)

- 3.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel T, Gottlieb DJ. Variations In The Longitudinal Efficiency Of Academic Medical Centers. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2004;(Suppl Web Exclusive):VAR 19–32. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.var.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottlieb D, Zhou W, Song Y, Andrews K, Skinner J, Sutherland J. Prices don’t drive regional Medicare spending variations. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2010;29:537–543. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClellan M, Skinner J. The incidence of Medicare. Journal of Public Economics. 2006;90:257–276. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutherland J, Fisher E, Skinner J. Getting past denial--the high cost of health care in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361:1227–1230. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0907172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuckerman S, Waidmann T, Berenson R, Hadley J. Clarifying Sources of Geographic Differences in Medicare Spending. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:54–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0909253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker L, Fisher E, Wennberg J. Variations in hospital resource use for medicare and privately insured populations in California. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2008;27:w123–134. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.w123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chernew M, Sabik L, Chandra A, Gibson T, Newhouse J. Geographic correlation between large-firm commercial spending and Medicare spending. American Journal of Managed Care. 2010;16:131–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothman K, Greenland S, Lash T. Validity in Epidemiologic Studies. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash T, editors. Modern Epidemiology. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. pp. 128–147. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glymour MM, Greenland S. Causal Diagrams. In: Rothman K, Greenland S, Lash T, editors. Modern Epidemiology. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. pp. 183–209. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneeweiss S, Rassen J, Glynn R, Avorn J, Mogun H, Brookhart M. High-dimensional propensity score adjustment in studies of treatment effects using health care claims data. Epidemiology. 2009;20:512–522. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a663cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rassen J, Glynn R, Brookhart M, Schneeweiss S. Covariate selection in high-dimensional propensity score analyses of treatment effects in small samples. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2011;173:1404–1413. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bross I. Spurious effects from an extraneous variable. J Chronic Dis. 1966;19:637–647. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(66)90062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneeweiss S. Sensitivity analysis and external adjustment for unmeasured confounders in epidemiologic database studies of therapeutics. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:291–303. doi: 10.1002/pds.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spiegelman D, Schneeweiss S, AM Measurement error correction for logistic regression models with an “alloyed gold standard”. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;145:184–196. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rassen JA, Choudhry NK, Avorn J, Schneeweiss S. Cardiovascular Outcomes and Mortality in Patients Using Clopidogrel With Proton Pump Inhibitors After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention or Acute Coronary Syndrome. Circulation. 2009;120:2322–2329. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.873497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuberg G. The cost of end-of-life care: A new efficiency measure falls short of AHA/ACC standards. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:127–133. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.829960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lash TL, Fox MP, Fink AK. Applying Quantitative Bias Analysis to Epidemiologic Data. 1. Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carroll R, Ruppert D, Stefanski L, Crainiceanu C. Measurement Error in Nonlinear Models: A Modern Perspective. 2. Boca Raton, Florida: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2006. [Google Scholar]