Abstract

Purpose

To assess outcomes of language, verbal memory, cognitive efficiency and mental flexibility, mood, and quality of life (QOL) in a prospective, multicenter pilot study of Gamma Knife radiosurgery (RS) for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (MTLE).

Methods

RS, randomized to 20 Gy or 24 Gy comprising 5.5-7.5mL at the 50% isodose volume, was performed on mesial temporal structures of patients with unilateral MTLE. Neuropsychological evaluations were performed at preoperative baseline, and mean change scores were described at 12 and 24 months postoperatively. QOL data were also available at 36 months.

Key Findings

30 patients were treated and 26 were available for the final 24 month neuropsychological evaluation. Neither language (Boston Naming Test), verbal memory (California Verbal Learning Test and Logical Memory subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised), cognitive efficiency and mental flexibility (Trail Making Test), nor mood (Beck Depression Inventory) differed from baseline. QOL scores improved at 24 and 36 months, with those patients attaining seizure remission by month 24 accounting for the majority of the improvement.

Significance

The serial changes in cognitive outcomes, mood, and QOL are unremarkable following RS for MTLE. RS may provide an alternative to open surgery especially in those patients at risk of cognitive impairment or who desire a noninvasive alternative to open surgery.

Keywords: epilepsy surgery, radiosurgery, verbal memory, language, depression, quality of life

Introduction

Gamma Knife radiosurgery (RS) has been reported as an alternative to open surgery in patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (MTLE). Although small case series vary in dose protocols and success in terms of seizure remission (for review see (Quigg and Barbaro 2008)), larger, multicenter studies demonstrate consistent positive results. A European, multicenter, prospective study demonstrates a two-year rate of seizure remission of 65% with the use of a 24 Gy 50% isodose volume encompassing the amygdala, anterior hippocampus, and the parahippocampal gyrus (Regis, et al. 2004). Our recent multicenter trial in which patients were randomized by dose and followed for three years reports a 59% remission rate in a 20 Gy group and a 77% remission in a 24 Gy group for an overall remission rate after three years of 67% (Barbaro, et al. 2009).

Cognitive outcomes from RS for MTLE are less well documented. Our initial report (Barbaro, et al. 2009) detailed verbal memory outcome quantified by two measures in terms of relative change indices that categorized patients by significant improvement, decline, or lack of change from pre-operative baselines. Of the 12 patients treated in the language-dominant temporal lobe, 3 (25%) experienced a significant decline on one measure of verbal memory, and 2 (16%) significantly improved in one.

The purpose of this report is to describe the details of the neuropsychological outcomes in our three-year pilot study of RS for MTLE (Barbaro, et al. 2009). This will include information regarding verbal memory testing, as well as other important measures such as language, cognitive efficiency and mental flexibility, mood, and quality of life (QOL). These secondary outcomes are important in evaluating the risks and benefits of this selective, noninvasive alternative to open surgery for MTLE.

Methods

Protocol and participants

Study design, protocols, and patient demographics are discussed in detail elsewhere (Barbaro, et al. 2009). This prospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of our multicenter group with patients providing informed consent. Briefly, patients had unilateral MTLE defined as complex partial seizures arising from a single temporal focus determined by video-EEG concordant to unilateral hippocampal sclerosis on MRI. Patients were randomized to treatment with either a 20 Gy (low dose) or 24 Gy (high dose) protocol of Gamma Knife RS (Elekta AB, Stockholm, Sweden) containing a 50% isodose volume ranging from 5.5-7.5 mL comprising the amygdala, anterior hippocampus, and parahippocampal gyrus. The hemisphere of language dominance was evaluated with bilateral intracarotid amobarbital test (Wada test); “dominant” surgery refers to RS performed ipsilateral to the language-dominant hemisphere and “nondominant” refers to surgery on the language nondominant hemisphere. Neither “strength” of language lateralization nor memory lateralization were reported by treatment centers.

Patients maintained a standardized seizure diary that was reviewed with study personnel. Patients were designated “seizure-free” if they reported no seizures, excluding auras, equivalent to Engel’s outcome category Ib or better (Vickrey, et al. 1995) between postoperative months 18-24. This definition of seizure remission differed from the 24-36 month period used in our earlier report (Barbaro, et al. 2009) because of the corresponding postoperative duration of neuropsychological data used in the current study. In addition, the number of participants who had complete neuropsychological data differed from those with completed seizure diaries; therefore, the number of patients at each time point may differ from those reported earlier since only those who completed neuropsychological data were included in this analysis. Participants were administered a battery of neuropsychological tests at a preoperative baseline visit and at 12 and 24 months. QOL data were available at an additional 36 month assessment.

Cognitive efficiency and mental flexibility

To assess dominant hemisphere language function, we used the Boston Naming Test (BNT) as a measure of confrontation naming (Goodglass and Kaplan 1983). Verbal memory was assessed with the long delay free recall score of the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT-LDFR) (Delis, et al. 1987) and the delayed recall score of the Logical Memory subtest from the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised (WMSR-DR) (Wechsler 1987)). We assigned cut-off values for scores both to account for test-retest and practice effects. Accordingly, we designated patients as having “significant improvement”, “no change”, and “significant impairment” based on relative change indices (RCI) developed and validated in epilepsy populations (Hermann, et al. 1996, Sawrie, et al. 1996, Stroup, et al. 2003). Cut-off values for pre- to postoperative changes were as follows: CVLT-LDFR = (≤-3, ≥+7) and WMS-R-DR = (≤-7, ≥+13). We used the Trail Making Test Parts A and B (TMT-A, TMT-B) to measure simple and complex cognitive processing speed and mental flexibility as a marker of overall cerebral integrity (Reitan and Wolfson 1993). Only the original forms of these measures were used (i.e., alternate forms were not administered).

Mood

We assessed depressive symptoms with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). The BDI (Beck and Steer 1987) is a self-administered measure of individual depressive symptoms graded from absent to severe on a four point scale, with overall results ranging from 0 (not depressed) to 63 (maximally depressed). We used a cut-off score of depression (BDI ≥ 16) (Beck and Steer 1987, Devinsky, et al. 2005)to calculate the incidence of clinically significant depression (Beck and Steer 1987, Devinsky, et al. 2005).

QOL

We measured QOL with the use of a self-administered questionnaire, the Quality of Life in Epilepsy-10 (QOLIE-10). The QOLIE-10 (Cramer, et al. 1996) is derived from the longer QOLIE-89 (Devinsky, et al. 1995) and consists of ten questions scaled from 1 (best) to 5 (worst) regarding energy, mood, driving status, memory, employment status, social relationships, physical and mental symptoms and side effects, fear of impending events, and overall quality of life. The total QOLIE-10 score, ranging from 10-50, was determined from the sum of the individual 1–5 point scales, with lower numbers indicating better quality of life.

Data analysis

Means and standard deviations were used to describe baseline values and changes from baselines at 12, 24 and 36 months. Changes were expressed in terms of both absolute and percentage changes (the absolute change divided by baseline). Because of the limited number of patients in this pilot study (especially given the subgroups of RS side, dose, and seizure-remission), we chose to simply describe mean changes rather than conduct statistical hypothesis testing. To describe change scores in seizure-remission subgroups, patients were designated “seizure-free” if no complex partial seizures occurred in the preceding follow-up examination period so that patients at 12 months had to have no seizures between months 9-12, at 24 months between months 18-24, and at 36 months between months 24-36. The relationship of the seizure-free duration and QOL at the end of the three years was examined in the ordinary regression model, in which the QOL value assessed at 36 months is related to the patient’s seizure-free duration (in months) prior to the 36 months, adjusting for the side of surgery and QOL baseline value.

Results

Demographics of patients are shown in Table 1. Although proportionately more patients in the high dose group experienced seizure remission, this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Demographics of subjects randomized to treatment with radiosurgery for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Seizure remission in this trial was defined as the remission of complex partial seizures with or without remission of auras (Engels class IB or better) observed between 24-36 months after radiosurgery. Patients not finishing the trial were counted as unremitted.

| Age (years) | |

| mean ± standard deviation | 34.1 ± 7.9 |

| minimum - maximum | 34 - 60 |

|

| |

| Sex | |

| M:F | 12:18 |

|

| |

| Radiosurgery dose | |

| Low (20 Gy): High (24 Gy) | 17:13 |

|

| |

| Side of radiosurgery | |

| Language dominant: nondominant | 14:16 |

|

| |

| Seizure response | |

| Remitted: not remitted | |

| Total | 20:10 |

| Low dose | 10:7 |

| High dose | 10:3 |

Language and verbal memory

Overall there were no pervasive decreases in performance on tests of language and verbal memory for the patients treated in the dominant temporal lobe (Table 2). Patients who underwent high dose RS in the dominant temporal lobe demonstrated mild decreases in confrontation naming (BNT) and noncontextual verbal memory (CVLT). Patients who had dominant temporal lobe low dose RS did not demonstrate any declines in language or verbal memory. Patients who underwent RS of the nondominant temporal lobe had better language and verbal memory performance at baseline relative to patients with dominant temporal lobe epilepsy, and they did not demonstrate any apparent decline in cognition after RS. At the 12 month postsurgical point, no patients – neither language dominant nor nondominant side of surgery - experienced consistent impairments or improvements in both tests (Table 3). 5/14 (36%) of patients with dominant-side RS experienced significant impairment in at least test, and 1/16 (6%) experienced significant impairment after nondominant RS.

Table 2.

Mean absolute and percentage changes relative to baselines of language and verbal memory scores in patients with radiosurgery for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy divided into language dominant and nondominant surgeries.

| Dominant | Baseline | 12m post-pre | 24m post-pre | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | n | mean ± sd | n | mean ± sd | % mean ± sd | n | mean ± sd | % mean ± sd |

| BNT | ||||||||

| overall | 14 | 36.1 ± 13.7 | 14 | 0.4 ± 4.3 | 4 ± 18 | 12 | 0 ± 4.1 | 2 ± 17 |

| low | 8 | 34 ± 15.1 | 8 | 3 ± 2.3 | 13 ± 17 | 7 | 2.4 ± 3 | 12 ± 15 |

| high | 6 | 39 ± 12.4 | 6 | -3 ± 3.9 | -8 ± 11 | 5 | -3.4 ± 2.6 | -11 ± 8 |

| CVLT | ||||||||

| overall | 14 | 8.6 ± 3 | 14 | -0.5 ± 3.3 | 11 ± 70 | 12 | -1 ± 3.1 | -5 ± 35 |

| low | 8 | 7.3 ± 3.2 | 8 | 1.6 ± 2.5 | 43 ± 80 | 7 | 0.4 ± 1.8 | 10 ± 32 |

| high | 6 | 10.5 ± 1.1 | 6 | -3.3 ± 1.8 | -32 ± 16 | 5 | -3 ± 3.5 | -27 ± 28 |

| WMSR | ||||||||

| overall | 14 | 13.6 ± 6.9 | 14 | 1.3 ± 5.7 | 19 ± 55 | 12 | 2.6 ± 7.5 | 36 ± 71 |

| low | 8 | 16.3 ± 7.7 | 8 | 2.3 ± 6.7 | 36 ± 62 | 7 | 2.9 ± 9.5 | 48 ± 83 |

| high | 6 | 10.2 ± 4 | 6 | 0 ± 4.2 | -5 ± 37 | 5 | 2.2 ± 4.3 | 20 ± 53 |

|

| ||||||||

| Nondominant | Baseline | 12m post-pre | 24m post-pre | |||||

| Test | n | mean ± sd | n | mean ± sd | % mean ± sd | n | mean ± sd | % mean ± sd |

|

| ||||||||

| BNT | ||||||||

| overall | 16 | 48.1 ± 9.0 | 15 | 0.1 ± 9.2 | 0 ± 19 | 14 | 2.1 ± 2.5 | 4 ± 5 |

| low | 9 | 51.6 ± 5.8 | 8 | -2.8 ± 11.9 | -5 ± 23 | 8 | 1.5 ± 1.7 | 3 ± 3 |

| high | 7 | 43.6 ± 10.8 | 7 | 3.4 ± 3.0 | 8 ± 7 | 6 | 2.8 ± 3.4 | 7 ± 8 |

| CVLT | ||||||||

| overall | 15 | 10.1 ± 3.0 | 15 | 1.0 ± 2.8 | 10 ± 28 | 14 | 1.7 ± 2.9 | 17 ± 29 |

| low | 8 | 11.3 ± 3.0 | 8 | 0.1 ± 2.4 | 1 ± 21 | 8 | 0.4 ± 2.8 | 3 ± 25 |

| high | 7 | 8.7 ± 2.7 | 7 | 2.0 ± 3.0 | 23 ± 34 | 6 | 3.5 ± 2.3 | 40 ± 26 |

| WMSR | ||||||||

| overall | 16 | 20.6 ± 6.7 | 15 | 3.6 ± 5.5 | 18 ± 27 | 14 | 5.6 ± 5.4 | 27 ± 26 |

| low | 9 | 20.0 ± 5.9 | 8 | 5.5 ± 4.6 | 28 ± 23 | 8 | 5.0 ± 6.9 | 25 ± 35 |

| high | 7 | 21.3 ± 8.1 | 7 | 1.4 ± 6.0 | 7 ± 28 | 6 | 6.3 ± 2.7 | 30 ± 13 |

BNT= Boston Naming Test; CVLT= long delay free recall score of the California Verbal Learning Test; WMSR= delayed recall score of the Logical Memory subtest from the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised. In these tests, a positive change indicates an improvement in function. “Low” = 20 Gy RS dose; “High” = 24 Gy RS dose.

Table 3.

Distribution of significant impairments or improvements in verbal memory measured at 12 months after radiosurgery determined by relative change indices. This time corresponds to the point of maximal edema measured by MRI.

| Status | Dominant n=14 | Nondominant n=16 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No information | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

|

|

||||||

| CVLT | WMSR | Both | CVLT | WMSR | Both | |

|

|

||||||

| Improved | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| No change | 9 | 13 | 8 | 13 | 15 | 13 |

| Impaired | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

CVLT= long delay free recall score of the California Verbal Learning Test; WMSR= delayed recall score of the Logical Memory subtest from the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised. “Both” refers to cumulative number of patients experiencing significant impairment, improvement, or no changes in both the CVLT and WMSR. One patient (no information) was not available for neuropsychological testing at the 12 month postsurgical point.

Cognitive efficiency and mental flexibility

Cognitive efficiency and mental flexibility were evaluated for the whole sample (Table 4). Overall, the TMT-A and TMT-B scores improved over the two-year period. In the TMT-A test in the high dose group, there was a tendency for mean values to indicate a transient worsening in performance at 12 months when most patients had peak edema effects and to improve at 24 months when edema resolved.

Table 4.

Mean absolute and percentage changes relative to baselines in global cognition and mood scores in patients treated with radiosurgery for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy relative to baseline.

| Baseline | 12m post-pre | 24m post-pre | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | n | mean ± sd | n | mean ± sd | % mean ± sd | n | mean ± sd | % mean ± sd |

| TMTA | ||||||||

| overall | 30 | 30.7 ± 11.2 | 29 | 2.2 ± 14.1 | 10 ± 37 | 26 | -1.4 ± 11.5 | 1 ± 33 |

| low | 17 | 31.8 ± 12 | 16 | -0.4 ± 13.1 | 1 ± 29 | 15 | -3.3 ± 12.9 | -5 ± 27 |

| high | 13 | 29.2 ± 10.3 | 13 | 5.4 ± 15.1 | 21 ± 44 | 11 | 1.2 ± 9.1 | 8 ± 40 |

| TMTB | ||||||||

| overall | 30 | 74.5 ± 32.5 | 29 | 6.8 ± 25.1 | 9 ± 26 | 26 | -3.7 ± 19.5 | -2 ± 28 |

| low | 17 | 68.5 ± 27.8 | 16 | 8.7 ± 29.9 | 12 ± 29 | 15 | -0.8 ± 17.8 | 2 ± 27 |

| high | 13 | 82.5 ± 37.4 | 13 | 4.4 ± 18.5 | 6 ± 23 | 11 | -7.6 ± 21.9 | -8 ± 29 |

| BDI | ||||||||

| overall | 29 | 9.5 ± 7 | 29 | -0.6 ± 6.5 | -0.4 ± 68 | 26 | -0.4 ± 6.2 | -17 ± 72 |

| low | 16 | 8.8 ± 6.2 | 16 | -0.4 ± 5 | 4 ± 70 | 15 | 1.8 ± 6.3 | 3 ± 83 |

| high | 13 | 10.3 ± 8 | 13 | -0.9 ± 8.1 | -5 ± 68 | 11 | -3.4 ± 4.8 | -43 ± 48 |

BDI= Beck Depression Inventory; TMT-A/B= Trail Making Test, Parts A and B. For the TMT, a positive change indicates a decrement in performance. In the BDI, a positive change indicates worsening depression. “Low” = 20 Gy RS dose; “High” = 24 Gy RS dose.

Mood

Depression symptoms as evaluated by the BDI underwent no overall mean change (Table 4). The high dose group had greater improvement than the low dose group in both the first and second years. Preoperatively, four (15%) patients were depressed as identified by the BDI cutoff value. By 24 months postoperatively, two patients with previously normal mood became depressed, and one previously depressed patient improved, resulting in a net increase of one (total postoperative depressed = 5/26, 19%).

QOL

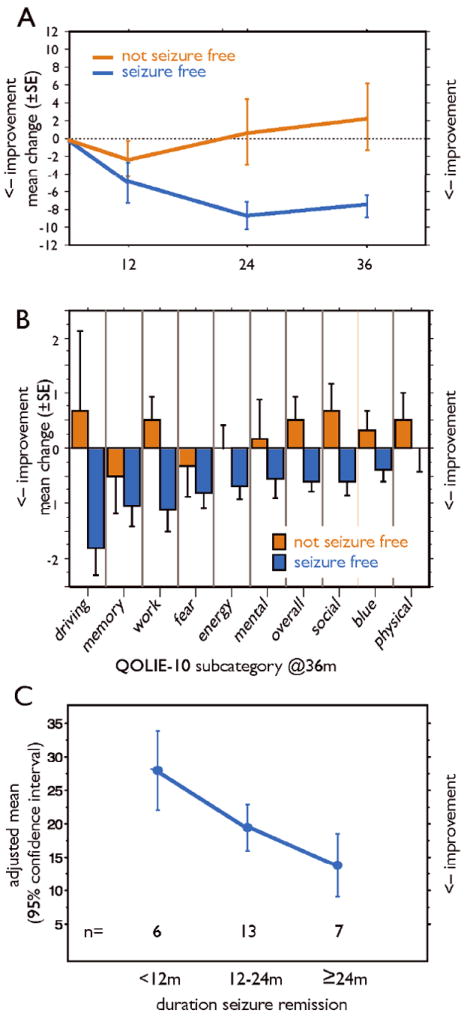

QOL scores were evaluated for the whole sample and were available at 12, 24, and 36 months postoperatively (Table 5). Overall, patients reported an improvement in QOL at the 24 and 36 postoperative period. The low dose group experienced an improvement in the first year and then maintained the same level of QOL over the next two years while the high dose group showed further improvement in year 2 and maintained that improvement by year 3. We found that at each annual postoperative mark, QOL improved in patients who were seizure-free at that time, but not in those whose seizures continued (Figure 2A). Regarding changes in individual QOLIE-10 questions, domains of driving, memory, work, and fear of impending seizures improved the most overall (Figure 2B). Driving, work, overall QOL, and social life differed the most by seizure status at 36m postoperatively. High-dose patients tended to experience longer, continuous seizure remission than low-dose patients (mean 18.0 months for the high-dose group versus 11.2 months for the low-dose group (Barbaro, et al. 2009). We were concerned that patients with shorter periods of seizure remission may experience worsened mood or QOL despite successful surgery. Longer duration of seizure remission was strongly associated with improved total QOLIE-10 scores after adjusting for baseline value and side of surgery (Figure 2C).

Table 5.

Mean absolute and percentage changes relative to baseline of the Quality of Life in Epilepsy – 10 (QOL) evaluated for patients at 12, 24, and 36 months after radiosurgery.

| Baseline | 12m post-pre | 24m post-pre | 36m post-pre | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | n | mean ± sd | n | mean ± sd | % mean ± sd | n | mean ± sd | % mean ± sd | n | mean ± sd | % mean ± sd |

| QOL | |||||||||||

| overall II | 30 | 25.2±5.3 | 29 | -3.0±8.5 | -9 ± 32 | 27 | -5.6±9.4 | -18±37 | 26 | -5.3±7.8 | -19±33 |

| low | 17 | 25.2±5.4 | 16 | -3.2±8.0 | -9 ± 33 | 15 | -3.5 ± 10.8 | -9±45 | 14 | -3.1±7.7 | -10±30 |

| high | 13 | 25.2±5.5 | 13 | -2.9±9.4 | -9 ± 32 | 12 | -8.3 ± 6.6 | -30±21 | 12 | -7.8±7.4 | -31±33 |

A negative change indicates an improved quality of life. “Low” = 20 Gy RS dose; “High” = 24 Gy RS dose.

Figure 1.

The Quality of Life in Epilepsy -10 scale (QOLIE-10). A. Mean ± SE changes in scores by seizure remission status at each annual visit. B. Mean ± SE changes in QOLIE-10 score subcategory scores by seizure-remission status at 36 months postoperatively. C. Association of duration of seizure remission and QOLIE-10 scores. Plotted are the estimated adjusted mean values at the end of three years with 95% confidence intervals, adjusting for side of the surgery and QOL baseline value.

Discussion

The main findings of this prospective pilot study of the neuropsychological outcomes of RS for MTLE were that cognitive measures of dominant hemisphere function, cognitive efficiency and mental flexibility, self-assessed depression, and measures of QOL remained stable at interim (12 month) and final (24 month) postoperative time points. In addition, QOL improved most markedly in those patients in whom seizures remitted and in those with the longest duration of seizure remission. These findings suggest that the morbidities of RS for MTLE in the domains of cognition, mood, and QOL are not substantially different than those expected for standard epilepsy surgery.

The description of serial changes in cognitive scores complement our earlier report in which we used reliable change indices to calculate that 25% of patients experienced significant changes of verbal memory after dominant hemisphere RS (Barbaro, et al. 2009). In comparison, 60% of dominant hemisphere anterior temporal lobectomy patients decline on at least one test of verbal memory when measured with relative change indices (Stroup, et al. 2003). Our findings of relative mean score changes of a 5±35% decrease in the CVLT and a 36±71% improvement in the WMSR compare favorably or remain within ranges (10-60%) reported after anterior temporal lobectomy (Chelune and Najm 2000, Hermann, et al. 1995, Hermann, et al. 1992, Seidenberg, et al. 1998, Stroup, et al. 2003). Evaluating the relative cognitive risks among surgical procedures is difficult because selection criteria and assessments differ. The findings of preservation of language and verbal memory may be explained in part by the “superselective” nature of the RS lesion. For example, some studies show that the more anatomically-limited resection of selective amygdala-hippocampectomy, as compared to anterior temporal lobectomy, leads to less impairment of dominant-hemisphere cognition (Clusmann, et al. 2002, Helmstaedter, et al. 2003) (Little, et al. 2009), although other studies show no clear advantages with more restricted resection (Jones-Gotman, et al. 1997, Wyler, et al. 1995). In addition, the noninvasive lesion of RS may spare connections with lateral temporal cortex that are hypothesized to mediate verbal memory (Ojemann and Dodrill 1985). The current findings supplement our earlier report in which we found no correlation of cognitive tests with the severity of transient, perilesional edema that peaks between 9-12 months and subsides thereafter (Chang, et al. 2010). The TMT-A and TMT-B evaluations, however, suggested trends of mild transient impairment in cognitive efficiency and flexibility at 12 months corresponding to the period of peak edemas as well as when many subjects had continuing seizures. Transient cognitive impairment is not well-reported in RS literature (Armstrong, et al. 2004). Based on our small cohort of patients, we present evidence that the severity of medial temporal lobe edema did not have transient effect on measures of cognition except for a relatively mild decrease in mental efficiency and mental flexibility. A larger trial currently underway will address this issue in detail.

There is limited information regarding neurocognitive effects of RS for MTLE. The only prospective, multicenter trial reports no significant cognitive changes through a two-year follow-up period (Regis, et al. 2004), but details are not specified. A small case series found no group changes at six months follow-up, although some individuals showed decline in at least one cognitive domain (Srikijvilaikul, et al. 2004). McDonald et al focused on cognitive outcomes on three patients stating that no consistent changes in cognition were found after dominant RS (McDonald, et al. 2004). Each patient, however, showed decline on at least one measure of verbal memory. They concluded that cognitive changes following RS appeared similar to those of standard surgery. A potential confounder of these studies was that the RS dose of 20 Gy used in that study may be too small to effectively treat seizures within the limited time-span of follow-up (Barbaro, et al. 2009, Quigg and Barbaro 2008). Furthermore, the neuropsychological follow up period may have been too short given the latency of development of the radiosurgical lesion (Barbaro, et al. 2009, Chang, et al. 2010, Regis, et al. 2004, Regis, et al. 1999).

Self-assessed depression did not change. Patients may experience worsening of mood during acute and subacute recovery after anterior temporal lobectomy (Carran, et al. 2003, Devinsky, et al. 2005, Glosser, et al. 2000, Quigg, et al. 2003). Most experience overall improvements in mood in longer term follow up (Devinsky, et al. 2005). One possible explanation for the finding that patients in the present study did not experience improvements in mood is that the time course of mood adjustment may differ between procedures, as most mood changes occur within the first six months after anterior temporal lobectomy (Glosser, et al. 2000). Because the latency to seizure remission after RS ranges from ~9-18 months (Barbaro, et al. 2009), improvements in mood may take longer to develop. We note that the rate of preoperative depression in the present study was less than half that reported in a prospective study of anterior temporal lobectomy (Devinsky, et al. 2005). The preoperative BDI was administered after patients were enrolled but before RS. One explanation for the low rate of preoperative depression in the current study could be selection bias, because patients were not randomized for entry. Another possibility may be that a noninvasive procedure confers a reduced level of preoperative anxiety or mood disturbance whereas stress and fear of open surgery may contribute to perioperative depression (Devinsky, et al. 2005). On the other hand, delays in seizure-remission may limit postoperative improvements in mood.

QOL data in this pilot study shed some light on the concern about the latency of seizure remission inherent in RS. In the present study, subjects who experienced seizure remission had significant improvements in QOL despite the delay in onset of effect. Nevertheless, longer seizure remission corresponded to improvements in QOL. The final improvements in QOL documented by the QOLIE-10 appear similar to those identified with the QOLIE-89 noted in earlier studies of psychological outcome (Hermann, et al. 1989); patients in the best seizure-outcome group experience the greatest improvement in QOL measures. We note, however, that in a large, more recent study, initial gains in QOL appear early after open surgery regardless of seizure remission(Spencer, et al. 2007). In the present study, latency to seizure remission and the absence of a longer postoperative recovery period after RS may combine in a fashion to facilitate the relatively larger improvements in the QOL domains of driving and work. Limitations in our comparisons arise from the abbreviated QOL tool used in the present study and in the small sample size.

Other limitations in general regarding this pilot study include the use of a limited subset of neuropsychological measures (albeit a battery upon which a variety of independent epilepsy centers could agree upon and which could be administered consistently). In addition, our inclusion/exclusion criteria included only those with hippocampal sclerosis; patients with other causes of temporal lobe epilepsy may be at more risk of deficits following temporal lobectomy (Davies, et al. 1998) whether performed through standard surgery or radiosurgical methods. Other causes of temporal lobe epilepsy (especially those in which the “epileptic zone” extends beyond the limbic system) may not be suited for RS since seizure remission rates appear lower than those whose foci are clearly associated with hippocampal sclerosis (Rheims, et al. 2008).

In summary, this report suggests that cognitive outcomes, mood, and QOL have similar postoperative courses as seen after open surgery. Based on our pilot data, we speculate that RS may incur no greater risk in neuropsychological outcome than open surgery and that delays in efficacy, inherent in the development of the RS lesion, do not prohibit improvements in QOL or result in an extra burden of depression. A prospective randomized trial of standard open surgery versus RS is currently underway and may provide further evidence regarding the effects of RS on neuropsychological functioning and whether cognitive abilities may be less adversely affected by RS relative to traditional open surgery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by Elekta (Stockholm, Sweden) and NIH grant NINDS R01 NS039280. We thank John Langfitt, PhD, of the University of Rochester for his editorial comments. We acknowledge the hard work and aide of the Radiosurgery Epilepsy Study Group: David Larson and Paul Garcia, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA; Ladislau Steiner, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA; Christie Heck, MD, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA; Douglas Kondziolka, MD, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA; Robert Beach, MD, State University of New York, Upstate Medical Center, Syracuse, NY; William Olivero, MD, Illinois Neurological Institute, Peoria, IL: Vicenta Salanova, MD, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IL; Robert Goodman, MD, Columbia University, New York, NY.

This study was sponsored by NIH NINDS [NS39280-03] and Elekta AB (Stockholm, Sweden).

Footnotes

Disclosures

Mark Quigg, MD MS reports no disclosures.

Mariann M. Ward, NP MS reports no disclosures.

Kenneth D. Laxer, MD reports no disclosures.

Donna K. Broshek, PhD reports no disclosures.

Nicholas M. Barbaro, MD reports no disclosures.

Kathleen Lamborn, PhD reports no disclosures.

Guofen Yan, PhD reports no disclosures.

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.”

References

- Armstrong CL, Gyato K, Awadalla AW, Lustig R, Tochner ZA. A critical review of the clinical effects of therapeutic irradiation damage to the brain: the roots of controversy. Neuropsychol Rev. 2004;14:65–86. doi: 10.1023/b:nerv.0000026649.68781.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaro NM, Quigg M, Broshek DK, Ward MM, Lamborn KR, Laxer KD, Larson DA, Dillon W, Verhey L, Garcia P, Steiner L, Heck C, Kondziolka D, Beach R, Olivero W, Witt TC, Salanova V, Goodman R. A multicenter, prospective pilot study of gamma knife radiosurgery for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: seizure response, adverse events, and verbal memory. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:167–175. doi: 10.1002/ana.21558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Steer R. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. Psychological Corp; San Antonio: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Carran MA, Kohler CG, O’Connor MJ, Bilker WB, Sperling MR. Mania following temporal lobectomy. Neurology. 2003;61:770–774. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000086378.74539.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EF, Quigg M, Oh MC, Dillon WP, Ward MM, Laxer KD, Broshek DK, Barbaro NM. Predictors of efficacy after stereotactic radiosurgery for medial temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 2010;74:165–172. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c9185d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelune GJ, Najm IM. Risk factors associated with postusurgical decrements in memory decline after anterior temporal lobectomy. In: Luders HO, Comair Y, editors. Epilepsy Surgery. Raven; Philadelphia: 2000. pp. 497–504. [Google Scholar]

- Clusmann H, Schramm J, Kral T, Helmstaedter C, Ostertun B, Fimmers R, Haun D, Elger CE. Prognostic factors and outcome after different types of resection for temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:1131–1141. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.5.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer J, Perrine K, Devinsky O, Meador K. A brief questionnaire to screen for quality of life in epilepsy: the QOLIE-10. Epilepsia. 1996;37:577–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies KG, Bell BD, Bush AJ, Hermann BP, Dohan FC, Jr, Jaap AS. Naming decline after left anterior temporal lobectomy correlates with pathological status of resected hippocampus. Epilepsia. 1998;39:407–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA. California Verbal Learning Test: research edition. Psychological Corp.; San Antonio: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Devinsky O, Barr WB, Vickrey BG, Berg AT, Bazil CW, Pacia SV, Langfitt JT, Walczak TS, Sperling MR, Shinnar S, Spencer SS. Changes in depression and anxiety after resective surgery for epilepsy. Neurology. 2005;65:1744–1749. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187114.71524.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devinsky O, Vickrey B, Cramer J, Perrine K, Hermann B, Meador K, Hays R. Development of the quality of life in epilepsy inventory. Epilepsia. 1995;36:1089–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glosser G, Zwil AS, Glosser DS, O’Conner MJ, Sperling MR. Psychiatric aspects of temporal lobe epilepsy before and after temporal lobectomy. J Neurology Neurosurgery Psychiatry. 2000;68:53–58. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodglass H, Kaplan E. Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination. Lea and Febiger; Philadelphia: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Helmstaedter C, Kurthen M, Lux S, Reuber M, Elger CE. Chronic epilepsy and cognition: a longitudinal study in temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:425–432. doi: 10.1002/ana.10692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann BP, Seidenberg M, Dohan FC, Jr, Wyler AR, Haltiner A, Bobholz J, Perrine A. Reports by patients and their families of memory change after left anterior temporal lobectomy: relationship to degree of hippocampal sclerosis. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:39–44. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199501000-00004. discussion 44-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann BP, Seidenberg M, Schoenfeld J, Peterson J, Leveroni C, Wyler AR. Empirical techniques for determining the reliability, magnitude, and pattern of neuropsychological change after epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia. 1996;37:942–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann BP, Wyler AR, Ackerman B, Rosenthal T. Short-term psychological outcome of anterior temporal lobectomy. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1989;71:327–334. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.71.3.0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann BP, Wyler AR, Bush AJ, Tabatabai FR. Differential effects of left and right anterior temporal lobectomy on verbal learning and memory performance. Epilepsia. 1992;33:289–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1992.tb02318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Gotman M, Zatorre RJ, Olivier A, Andermann F, Cendes F, Staunton H, McMackin D, Siegel AM, Wieser HG. Learning and retention of words and designs following excision from medial or lateral temporal-lobe structures. Neuropsychologia. 1997;35:963–973. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little AS, Smith KA, Kirlin K, Baxter LC, Chung S, Maganti R, Treiman DM. Modifications to the subtemporal selective amygdalohippocampectomy using a minimal-access technique: seizure and neuropsychological outcomes. J Neurosurg. 2009;111:1263–1274. doi: 10.3171/2008.10.17673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald CR, Norman MA, Tecoma E, Alksne J, Iragui V. Neuropsychological change following gamma knife surgery in patients with left temporal lobe epilepsy: a review of three cases. Epilepsy Behav. 2004;5:949–957. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojemann GA, Dodrill CB. Verbal memory deficits after left temporal lobectomy for epilepsy. Mechanism and intraoperative prediction. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:101–107. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.1.0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigg M, Barbaro NM. Stereotatic radiosurgery for treatment of epilepsy. Archives Neurology. 2008;65:177–183. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigg M, Broshek DK, Heidal-Schiltz S, Maedgen JW, Bertram EH. Depression in intractable partial epilepsy varies by laterality of focus and surgery. Epilepsia. 2003;44:419–424. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.18802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regis J, Rey M, Bartolomei F, Vladyka V, Liscak R, Schrottner O, Pendl G. Gamma knife surgery in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: a prospective multicenter study. Epilepsia. 2004;45:504–515. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.07903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regis J, Semah F, Bryan RN, Levrier O, Rey M, Samson Y, Peragut JC. Early and delayed MR and PET changes after selective temporomesial radiosurgery in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:213–216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Theory and clinical interpretation. Neuropsychology Press; Tucson, AZ: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rheims S, Fischer C, Ryvlin P, Isnard J, Guenot M, Tamura M, Regis J, Mauguiere F. Long-term outcome of gamma-knife surgery in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Research. 2008;80:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawrie SM, Chelune GJ, Naugle RI, Luders HO. Empirical methods for assessing meaningful neuropsychological change following epilepsy surgery. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 1996;2:556–564. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700001739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidenberg M, Hermann B, Wyler AR, Davies K, Dohan FC, Jr, Leveroni C. Neuropsychological outcome following anterior temporal lobectomy in patients with and without the syndrome of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuropsychology. 1998;12:303–316. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.12.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer SS, Berg AT, Vickrey BG, Sperling MR, Bazil CW, Haut S, Langfitt JT, Walczak TS, Devinsky O. Health-related quality of life over time since resective epilepsy surgery. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:307–308. doi: 10.1002/ana.21131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikijvilaikul T, Najm I, Foldvary-Schaefer N, Lineweaver T, Suh JH, Bingaman WE. Failure of gamma knife radiosurgery for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: report of five cases. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:1395–1402. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000124604.29767.eb. discussion 1402-1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup E, Langfitt J, Berg M, McDermott M, Pilcher W, Como P. Predicting verbal memory decline following anterior temporal lobectomy (ATL) Neurology. 2003;60:1266–1273. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000058765.33878.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickrey B, Hays R, EngelJ J, Spritzer K, Rogers W, R R, Graber J, Brook R. Outcome assessment for epilepsy surgery: the impact of measuring health-related quality of life. Annals of Neurology. 1995;37:158–166. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised Manual. Psychological Corp; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wyler A, Hermann B, Somes G. Extent of medial temporal resection on outcome from anterior temporal lobectomy: a randomized prospective study. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:982–990. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199511000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.