Abstract

Recent price spikes1,2 have raised concern that climate change could increase food insecurity by reducing grain yields in the coming decades3,4. However, commodity price volatility is also influenced by other factors5,6, which may either exacerbate or buffer the effects of climate change. Here we show that US corn price volatility exhibits higher sensitivity to near-term climate change than to energy policy influences or agriculture-energy market integration, and that the presence of a biofuels mandate enhances the sensitivity to climate change by more than 50%. The climate change impact is driven primarily by intensification of severe hot conditions in the primary corn-growing region of the US, which causes US corn price volatility to increase sharply in response to global warming projected over the next three decades. Closer integration of agriculture and energy markets moderates the effects of climate change, unless the biofuels mandate becomes binding, in which case corn price volatility is instead exacerbated. However, in spite of the substantial impact on US corn price volatility, we find relatively small impact on food prices. Our findings highlight the critical importance of interactions between energy policies, energy-agriculture linkages, and climate change.

Price volatility – particularly sharp upward price spikes – has long characterized commodity markets1. However, the recent price run-ups have been attributed to more pronounced ‘market inelasticity’ associated with constraints on global land supply, biofuel policy mandates, depleted stocks, and disruptive trade policies – all of which reduce the ease of adjustment in the face of temporary scarcity2. In addition, grain supply shortfalls are often caused by adverse weather events in major producing regions of the world. The likelihood of increasing occurrence of severe hot events in response to increasing global greenhouse gas concentrations7 poses a particular risk for field crops, which have historically shown high sensitivity to severe heat3,4.

A key unknown is whether increasing stress from climate extremes will influence yield volatility in addition to overall yield levels. Yield volatility can be measured in terms of deviations from some long run average, or as the variability in year-to-year changes in yields. In this work, we favor the latter metric, as it reflects those changes that are more likely to influence markets, including sensitivity to extreme events of the sort that cause market disruptions. (By way of comparison, the 1980–2000 standard deviation of year-on-year US national yield ratios (20%) is almost double the standard deviation of detrended US national yields (11%)8.) The potential for increasing yield volatility is of particular concern within the context of the recent increase in market inelasticity2. Indeed, the combination of a binding renewable fuels standard for corn ethanol and capacity constraints on ethanol absorption (the so-called ‘blend wall’) in the US could cause US corn price volatility to increase by more than 50% in response to historical supply shocks in the domestic market6.

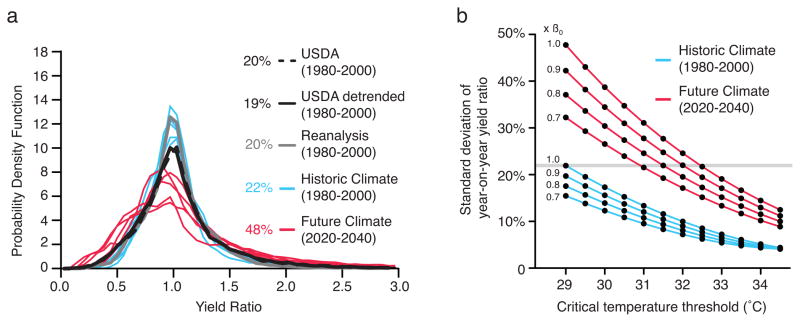

We seek to quantify the sensitivity of US corn price volatility to (1) near-term changes in climate volatility, (2) the extent of agriculture-energy market integration, (3) the presence of the US biofuels mandate, and (4) future oil price trajectories. To our knowledge, this is one of the first attempts to draw out the price effects of climate volatility – particularly in the context of related economic policies. To enable this quantification, we employ a one-way climate-agriculture-economic modeling framework (Fig. S1). We first project twenty-first century changes in temperature and precipitation using an ensemble of high-resolution climate model experiments9 (see Methods). We then simulate the response of US corn yields to climatic conditions using a statistical model3 (see Methods). Finally, we simulate the commodity market impacts of yield volatility using the GTAP-BIO-AEZ model10, which allows us to both project the future bio-economy under both low ($53/bbl) and high ($169/bbl) oil price projections11 and examine the impacts of biofuel mandates under each of these future economies (see Methods). Our approach simulates national-scale corn yield volatility that is very close to the observed value (standard deviations of 22% and 20%, respectively, for simulated and observed year-on-year yield ratios over the 1980–2000 period; see Supplemental Information (SI)). Likewise, the standard deviation of year-on-year US percentage corn price changes induced by the supply-side shocks to the economic model is very close to the observed value (25% and 28%, respectively, for simulated and observed year-on-year percentage price changes over the 1990–2009 period; see SI).

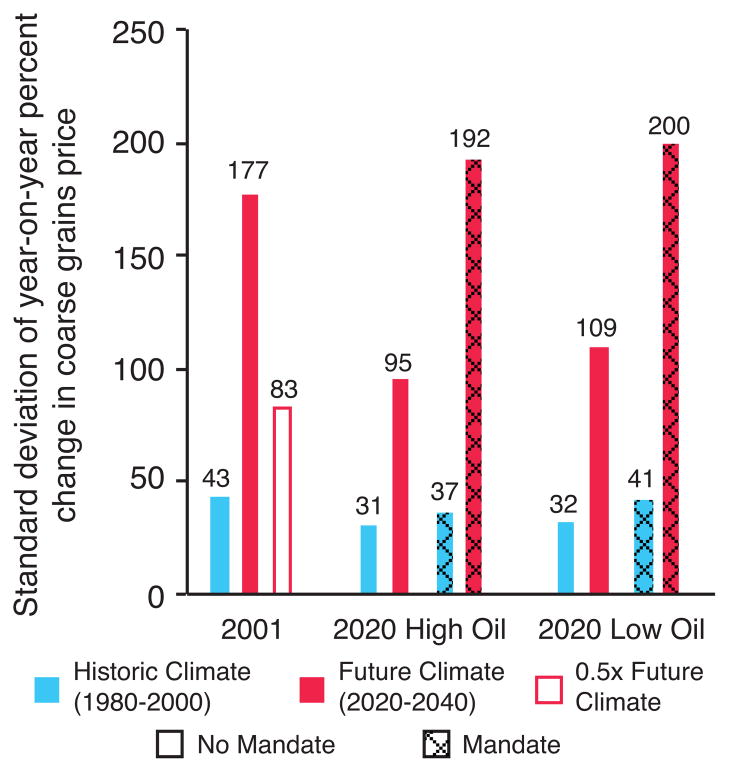

We find that climate change increases US corn price volatility by a factor of 4.1 in the historic economy (from 43% to 177%; Fig. 1.) The amplification of corn price volatility results from a doubling of supply volatility in the future climate, with the standard deviation of year-on-year corn yield ratios increasing from 22% in the historic period to 48% in the future period (Fig. 2). (An increase in yield volatility that is only half as large leads to a doubling of price volatility, suggesting that the price response to changing supply volatility is fairly linear in the context of the historic economy; Fig. 1.) The response of price volatility to the climate-change-induced doubling of supply volatility is reduced to a factor of 3.1 (high oil price) and 3.4 (low oil price) in the 2020 economy if the biofuels mandate is not in place. This decline in sensitivity of price volatility arises from the increased share of corn sales into the relatively price-responsive liquid fuel market – in the absence of a mandate (see SI). In contrast, the effect of climate change on US corn price volatility is increased to a factor of 5.3 (high oil prices) and 4.8 (low oil prices) if the biofuels mandate is kept in place in 2020.

Figure 1. Standard deviation of year-on-year percent change in US corn prices under alternative climate, policy and economic scenarios.

Each bar shows the standard deviation of US corn prices in the historic (blue) and future (red) climate, in the presence (hashed) or absence (unhashed) of the biofuels mandate and high ($169/bbl) or low ($53/bbl) oil price (see Methods and SI for details). The number above each vertical bar reports the value of year-on-year price volatility in that model prescription. The white bar shows price volatility for half of the future change in yield volatility. (See SI for additional sensitivity analysis.)

Figure 2. US corn yield ratios in the historic and future climate.

(a) Observed and simulated distributions of yield ratios (yt/yt−1). The colored numbers show the standard deviation of year-on-year yield ratios, including the mean of the standard deviations from the five realizations. The confidence intervals for α and β reported by Schlenker and Roberts give volatility ranges of 20–24% and 43–53% for the simulated historic and future climates, respectively. (b) Curves show the response of US corn yield ratio volatility to changes in the critical temperature threshold for different fractions (x β) of the Schlenker-Roberts β value denoting the associated yield penalty.

The sensitivity of US corn price volatility to developments in the biofuels market is greater within the context of the future climate than the historic climate (Fig. 1). For instance, in the context of the 2020 economy and low oil prices, elimination of the biofuels mandate reduces corn price volatility from 41% to 32% in the historic climate, while elimination of the mandate reduces price volatility from to 200% to 109% in the future-climate/low-oil scenario. It is therefore clear that the mandate, which has a substantial impact on US corn price volatility under historic climate, has an even greater impact in the context of near-term climate change.

The impact of the mandate on US corn price volatility is intimately related to the degree of integration between the agricultural and energy economies6. In principle, the liquid fuel market offers a very price-elastic demand source, which can serve as a buffer against supply-side shocks in the corn market. When yields are above normal and prices are low, biofuel production can expand to absorb the surplus; when yields are low and prices are high, biofuel plants can temporarily shut down and release corn supplies for livestock and food uses. This is evidenced by an increase in the absolute value of the general equilibrium elasticity of demand for US corn under the 2020 high oil scenario, which is driven by price responsive biofuel sales (Fig. S2, dark green bar). Thus, the lowest price volatilities exist in the 2020 scenarios, with historic climate and no mandate (Fig. 1). The smallest (in absolute value) demand elasticity arises in the 2020 scenario when the mandate remains in place. In this case, the larger share of corn sales to ethanol, coupled with the lack of price responsiveness in these sales, results in extremely volatile corn prices in response to supply-side shocks. This volatility is comparable to that in 2001 when biofuel sales were negligible, and it is dramatically larger than in the 2020 high oil scenario under future climate. (We note that the mandate is binding in 44% of the simulations under the combined future-climate/high-oil-price scenario, and arises when the US corn yield shock is adverse.)

The national-level increase in yield volatility (Fig. 2) is driven primarily by increases in yield volatility in the US Corn Belt region (Fig. S3), which exhibits increases of 100% to 160% in growing degree days (GDD) above 29°C, increases of up to (and in places exceeding) 50% in growing season precipitation, and increases of less than 6% in GDD between 10°C and 29°C (Fig. S3). Near-term climate change substantially increases the yield response-weighted volatility of all three climate variables (including increases of greater than 100% in yield response-weighted volatility of GDD above 29°C throughout the Corn Belt region; Fig. S3), doubling the national-level US corn yield volatility (Fig. 2).

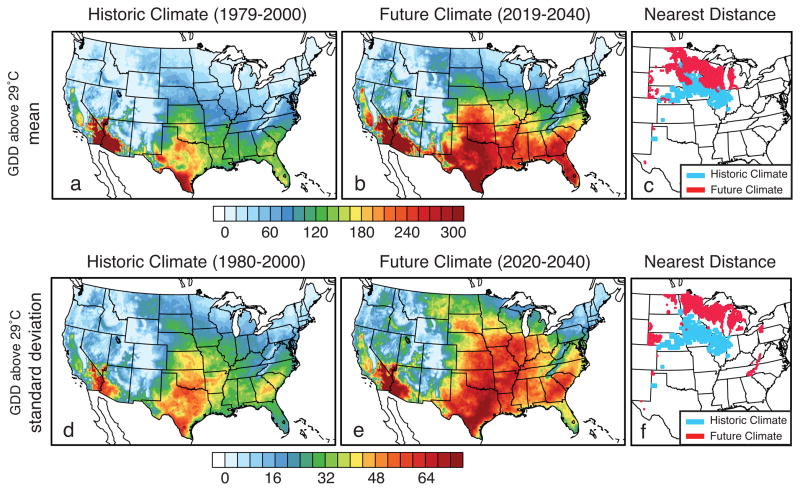

The capacity to adapt to climate change through the development of new, heat tolerant varieties and/or shifts in the geographic concentration of corn production could help to alleviate the impacts of severe heat on corn yields. Restoring the current level of US corn yield ratio volatility within the context of future climate would require increasing the critical threshold from 29°C to 32.5°C for the current regression coefficients, or to 31.0°C for a severe-heat penalty that is 0.7 of the present value (Fig. 2). In addition, in the future climate, the nearest areas of equivalent mean and standard deviation of GDD between 10 and 29°C exhibit a high degree of overlap with the current US Corn Belt (Fig. S4), but the nearest areas of equivalent mean and standard deviation of GDD above 29°C are located considerably northward (Fig. 3). The need for changes in heat tolerance or growing location will be reduced if the actual near-term climate change is smaller than projected here, although the CMIP3 global climate model ensemble shows 21st century warming of at least 2°C/century over the central US12. Likewise, the physiological response to increasing ambient CO2 concentrations could alter the crop response to climate change13,14, although the effect on the year-on-year corn yield ratio volatility is uncertain14.

Figure 3. Nearest distance to equivalent temperature envelope in the future climate.

Color contours show GDD above 29°C in the historic (left panels) and future (center panels) climate. The blue area in the right panels shows the county weights in US corn production exceeding 0.18% in the 1979–2000 period; the red area shows the grid points in the future climate that exhibit the minimum grid-point distance to a GDD value within 1 GDD of each of the blue grid points. Each gridpoint is allowed to be occupied only once in the future climate (see SI for details).

The price response to increased supply volatility could also be altered by several factors from which we have abstracted (Fig. S5). Any increase in year-on-year price volatility will increase the incentive for stockholding as a strategy for benefitting from greater price spikes. However, as with many studies, we subsume the stockholding response into consumers’ overall price responsiveness of demand, thereby over-stating the latter1. This abstraction makes it impossible to examine the interplay between increased year-on-year volatility and the private sector incentives for accumulating stocks and releasing them in low yield years – which will have a moderating influence on prices. Likewise, we have not factored in the response of corn producers to the increased price risk, which is likely to further moderate their response to price shocks15. In addition, we abstract from the impacts of changes in climate volatility on other crops in the US as well as impacts in the rest of the world. As a result, the impact of the climate-induced increase in corn price volatility on overall food prices in the US and other countries is quite small (see SI). However, these effects could be much larger if similar increases in severe events occur simultaneously in other growing regions16, as is projected by numerous global climate model simulations7.

Our treatment of the ethanol mandate and energy prices presents a final set of limitations. We treat this mandate as being commodity-specific, on the assumption that other biofuels are unlikely to displace corn ethanol over the near-term period17. However, in reality the US Renewable Fuels Standard is far more complex18. Also, incremental waivers19 relaxing the stringency of the ethanol mandate are more likely than the complete elimination that we have prescribed here. Indeed, such waivers have already been granted for cellulosic biofuels, and the waiver option is a great source of potential uncertainty in these markets20. Finally, the strengthened linkages between the corn and fuel markets suggested by our results would increase exposure to inter-annual variability in oil prices, presenting an additional source of uncertainty.

Notwithstanding these important caveats, we conclude that economic influences can interact with increased climate volatility to generate significant commodity price variability in the near-term decades (Fig. S5). Our results suggest that increased GHG concentrations are likely to lead to increased frequency and intensity of severely hot temperatures in the US Corn Belt, leading to increases in year-on-year variability in US corn yields and increases in US corn price volatility. This increased price volatility in response to supply side shocks will be dampened by closer integration of the corn and energy markets. However, such integration increases the exposure to oil price uncertainty, and increases the influence of biofuel mandates, which amplify the price response to yield volatility by promoting market inelasticity. Our results therefore suggest that energy markets and associated policy decisions could substantially exacerbate the impacts of climate change, even for the relatively modest levels of global warming that are likely to occur over the near-term decades.

Methods

We employ a high-resolution climate model ensemble9 in which the ICTP RegCM3 limited-area climate model21 is nested within the NCAR CCSM3 global climate model22 at 25-km horizontal resolution over the continental US24, generating five high-resolution simulations of the 1950–2040 period in the SRES A1B emissions scenario23. We remove the bias in the five climate model realizations using a quantile-based bias correction method25,26, which substantially improves the simulation of temperature extremes over the central US25. Further details of the climate model simulations and the bias correction are included in the SI.

We calculate corn yield ratios using the Schlenker-Roberts yield function3, which predicts corn yields in county i and year t from growing degree days, precipitation, county fixed effects and a time trend for technology. By differencing two successive years, this statistical model can be used to calculate the year-on-year yield change as the yield ratio:

| (1) |

where are the growing season (March 1st – August 31st) growing degree days (GDD) between the base of 10°C and 29°C, are the growing season GDD above 29°C, and are the total growing season precipitation (cm/m2). The estimated coefficients3 are α = 3.15512·10−4, β = −6.43807·10−3, δ1 = 1.02821·10−2 and δ2 = 8.15140·10−5. For purposes of analyzing climate-induced commodity market volatility, we aggregate to the national level using county production shares:

| (2) |

We calculate the yield ratios in both the historic (1979–2000) and future (2019–2040) climate. The standard deviation of historical yield ratios calculated using the bias-corrected high-resolution climate simulations (22%) agrees with the observed value (20%) (see also Fig. 2). Further details of the yield calculation are included in the SI.

We employ the global economic model GTAP-BIO-AEZ10, which integrates agricultural and energy markets and allows for explicit modeling of biofuel policies. The model has been validated in stochastic mode in the context of random shocks to supply and demand in agriculture 27 and energy markets28. We validate the model by undertaking an historic simulation over the 2001–2008 period as well as by undertaking a stochastic simulation analysis wherein we sample from the observed 1990–2009 year-on-year yield distribution and predict corn price volatility in the context of the 2008 economy. The resulting standard deviation of model-predicted year-on-year price changes (25%) is in agreement with the standard deviation of observed, detrended, year-on-year percentage price changes (28%). We also examine the sensitivity of our findings to uncertainties in the economic model parameters, and find the results to be robust (see SI).

We generate a baseline scenario for the period 2008–2020 in which we shock total factor production, population, labor force, investment, and oil prices (see SI for list of variables). We focus special attention on the state of the biofuel mandate in 2020. We allow the mandated level of ethanol production to rise in accordance with current estimates, factoring in developments in other renewable fuels from FAPRI29. We find that our model conforms with FAPRI’s prediction that the mandate will be binding in 2020. Having established this baseline projection for the global economy to 2020, we then re-run these economic projections from 2008 to 2020 imposing alternately the low and high oil price trajectories. We find that, without climate change, the biofuels mandate is severely binding in the low oil price scenario (recall that it was already binding in the reference scenario), but that the mandate becomes non-binding in the high oil price scenario, causing ethanol production to exceed the mandate by 17%. Further details of the economic modeling are included in the SI.

Given that the calculated US corn yield volatility is twice as high in the future climate as in the historic climate (Fig. 2), we test the effect of climate change by doubling the US corn yield volatility in the GTAP model. This doubling is applied in 3 sets of “multi-factor” economic model simulations that test the interaction of climate change with energy markets and policies (Fig. 1): (i) the 2001 economy, with corn yield volatility calculated from either historic or future climate (2 simulations); (ii) the 2020 economy with high oil prices, with yield volatility calculated either from the historic or future climate, with or without the biofuels mandate (4 simulations); and (iii) the 2020 economy with low oil prices, with yield volatility calculated from either the historic or future climate, with or without the mandate (4 simulations).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for insightful and constructive comments from three anonymous reviewers, as well as from participants in the International Agricultural Trade Consortium theme day and the Stanford Environmental Economics Seminar series. We thank NCEP for providing access to the NARR dataset, and the PRISM Climate Group for providing access to the PRISM observational dataset. We thank the Rosen Center for Advanced Computing (RCAC) at Purdue University and the Center for Computational Earth and Environmental Science (CEES) at Stanford University for access to computing resources. The research reported here was primarily supported by the U.S. DOE, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, Integrated Assessment Research Program, Grant No. DE-SC005171, along with supplementary support from NSF award 0955283 and NIH award 1R01AI090159-01.

Footnotes

Author contributions

NSD designed and performed the climate modeling, designed the climate-yield-economic modeling approach, analyzed the results, and wrote the paper. TWH designed the climate-yield-economic modeling approach, designed the economic modeling, analyzed the results, and wrote the paper. MS designed the climate-yield-economic modeling approach, performed the yield calculations, and analyzed the results. MV designed the climate-yield-economic modeling approach, performed the economic modeling, analyzed the results, and wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Wright BD. The economics of grain price volatility. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. 2011;33:32–58. doi: 10.1093/aepp/ppq033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbott P, Hurt C, Tyner WE. What’s driving farm prices in 2011? Farm Foundation Issue Report; Chicago: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schlenker W, Roberts MJ. Nonlinear temperature effects indicate severe damages to US crop yields under climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2009. pp. 15594–15598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battisti DS, Naylor RL. Historical Warnings of Future Food Insecurity with Unprecedented Seasonal Heat. Science. 2009;323:240–244. doi: 10.1126/science.1164363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson K, Nelgen S. Trade barrier volatility and agricultural price stabilization. World Development. 2011;40:36–48. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hertel TW, Beckman J. In: The Intended and Unintended Effects of US Agricultural and Biotechnology Policies. Zivin JG, Perloff J, editors. NBER and University of Chicago Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diffenbaugh NS, Scherer M. Observational and model evidence of global emergence of permanent, unprecedented heat in the 20th and 21st centuries. Clim Change. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10584-011-0112-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.USDA. National Agricultural Statistics Service Quick Stats. 2011 http://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/

- 9.Diffenbaugh NS, Ashfaq M. Intensification of hot extremes in the United States. Geophys Res Lett. 2010;37:L15701. 15710.11029/12010GL043888. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taheripour F, Hertel TW, Tyner WE. Implications of biofuels mandates for the global livestock industry: a computable general equilibrium analysis. Agricultural Economics. 2011;42:325–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-0862.2010.00517.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.EIA. Annual Energy Outlook 2010. Energy Information Agency, U.S. Department of Energy; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diffenbaugh NS, Ashfaq M, Scherer M. Transient regional climate change: Analysis of the summer climate response in a high-resolution, century-scale ensemble experiment over the continental United States. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2011;116 doi: 10.1029/2011JD016458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ainsworth EA, Leakey ADB, Ort DR, Long SP. FACE-ing the facts: inconsistencies and interdependence among field, chamber and modeling studies of elevated CO2 impacts on crop yield and food supply. New Phytol. 2008;179:5–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leakey ADB. Rising atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration and the future of C4 crops for food and fuel. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2009;276:2333–2343. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gohin A, Treguer D. On the (de)stabilization effects of biofuels: relative contributions of policy instruments and market forces. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics. 2010;35:72–86. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed SA, Diffenbaugh NS, Hertel TW, Martin WJ. Agriculture and trade opportunities for Tanzania: past volatility and future climate change. Review of International Economics. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 17.NRC. Renewable Fuel Standard: Potential Economic and Environmental Effects of US Biofuel Policy. National Research Council; Washington, D.C: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson W, Meyer S, Weshoff P. The new markets for renewable identification numbers. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. 2010;32:588–603. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodlatte R. ed 112th Congress: 2011–2012; United States House of Representatives, Washington, D.C. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson W, Meyer S. EPA mandate waivers create new uncertainties in biodiesel markets. Choices. 2011;26 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pal JS, et al. Regional climate modeling for the developing world: the ICTP RegCM3 and RegCNET. Bull Amer Meteorol Soc. 2007;89:1395–1409. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins WD, et al. The Community Climate System Model version 3 (CCSM3) J Clim. 2006;19:2122–2143. [Google Scholar]

- 23.IPCC, W. G. I. Special Report on Emissions Scenarios. Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diffenbaugh NS, Pal JS, Trapp RJ, Giorgi F. Fine-scale processes regulate the response of extreme events to global climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:15774–15778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506042102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashfaq M, Bowling LC, Cherkauer K, Pal JS, Diffenbaugh NS. Influence of climate model biases and daily-scale temperature and precipitation events on hydrological impacts assessment: a case study of the United States. Journal of Geophysical Research. 2010;115:D14116. 14110.11029/12009JD012965. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashfaq M, Skinner CB, Diffenbaugh NS. Influence of SST biases on future climate change projections. Clim Dyn. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00382-00010-00875-00382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valenzuela E, Hertel TW, Keeney R, Reimer JJ. Assessing global computable general equilibrium model validity using agricultural price volatility. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2007;89 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beckman J, Hertel T, Tyner W. Validating energy-oriented CGE models. Energy Economics. 2011;33:799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2011.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.FAPRI. US Biofuels Baseline: The Impact of Extending the $045 Ethanol Blenders Credit, Report #07–11, June 2011. Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute of the University of Missouri; 2011. [Google Scholar]