Abstract

No chemotherapeutic drug can be effective until it is delivered to its target site. Nano-sized drug carriers are designed to transport therapeutic or diagnostic materials from the point of administration to the drug’s site of action. This task requires the nanoparticle carrying the drug to complete a journey from the injection site to the site of action. The journey begins with the injection of the drug carrier into the bloodstream and continues through stages of circulation, extravasation, accumulation, distribution, endocytosis, endosomal escape, intracellular localization and—finally—action. Effective nanoparticle design should consider all of these stages to maximize drug delivery to the entire tumor and effectiveness of the treatment.

Keywords: drug delivery, nanomedicine, cancer, EPR, extravasation, diffusion, tumor heterogeneity, multidrug resistance

1. Introduction

1.1. The first victory against metastatic cancer

It has been more than sixty years since Sidney Farber conducted the first successful trial of a chemotherapeutic agent against a nonresectable cancer. Having discovered that acute leukemia was overly dependent on folate, he surmised that the folate antagonist aminopterin may inhibit white blood cell proliferation and stop the cancer’s spread. Most patients responded to the treatment, but relapsed within six months to a year, bearing a more aggressive and resistant form of the cancer [1]. In spite of the disappointment from the relapse of the cancer, the trial was rightfully hailed as a tremendous success. For the first time, doctors had a weapon to wield against metastatic cancer. The ensuing decades brought many advancements to chemotherapeutic treatments. Acute leukemia, which was a sentence of certain death in 1947, held a 60 percent survival rate only 30 years later. The treatment of other cancers was similarly revolutionized in the same time period [2].

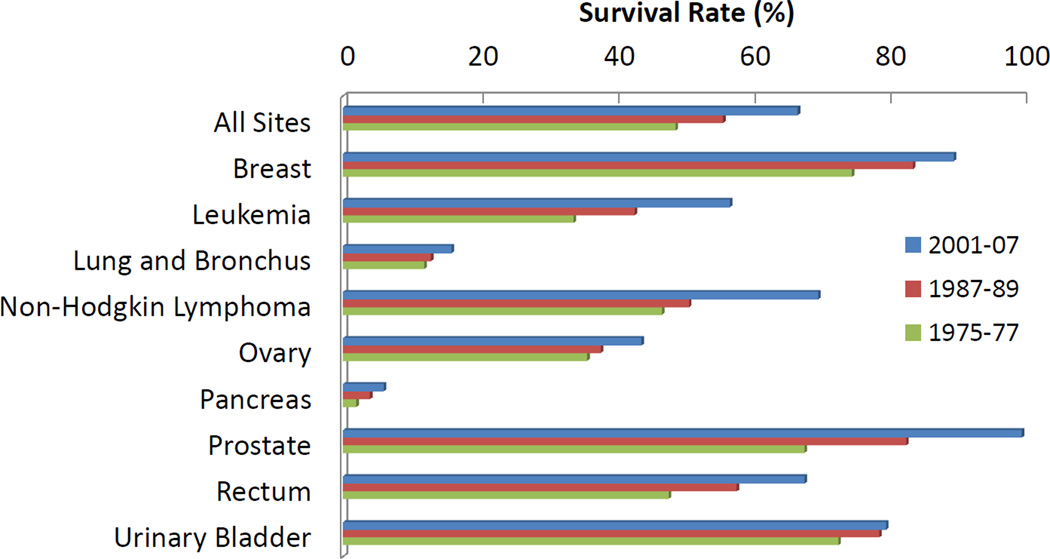

The introduction of chemotherapy as a revolutionary cancer treatment led to tremendous optimism regarding the prospects of finally finding a cure for cancer. In lobbying for the National Cancer Act, Farber himself advised in 1969 that, “[w]e are so close to a cure for cancer. We lack only the will and the kind of money and comprehensive planning that went into putting a man on the moon” [3]. The National Cancer Act became law in 1971, but the promised “cure for cancer” never materialized. After investing billions of dollars and tremendous research focus, only incremental gains, which are largely attributed to improved diagnostic techniques allowing earlier intervention, against cancer have been achieved (see Figure 1) [4]. More than 60 years after Farber’s initial trial, traditional chemotherapy is still our frontline treatment against cancer [5].

Figure 1. Recent progress in cancer survival rates.

In the past several decades steady progress has been made in treating tumors and some sites have shown impressive cure rates. While this progress is encouraging, no revolutionary “cure” has been discovered in spite of several promising new technologies, including nanomedicine [4].

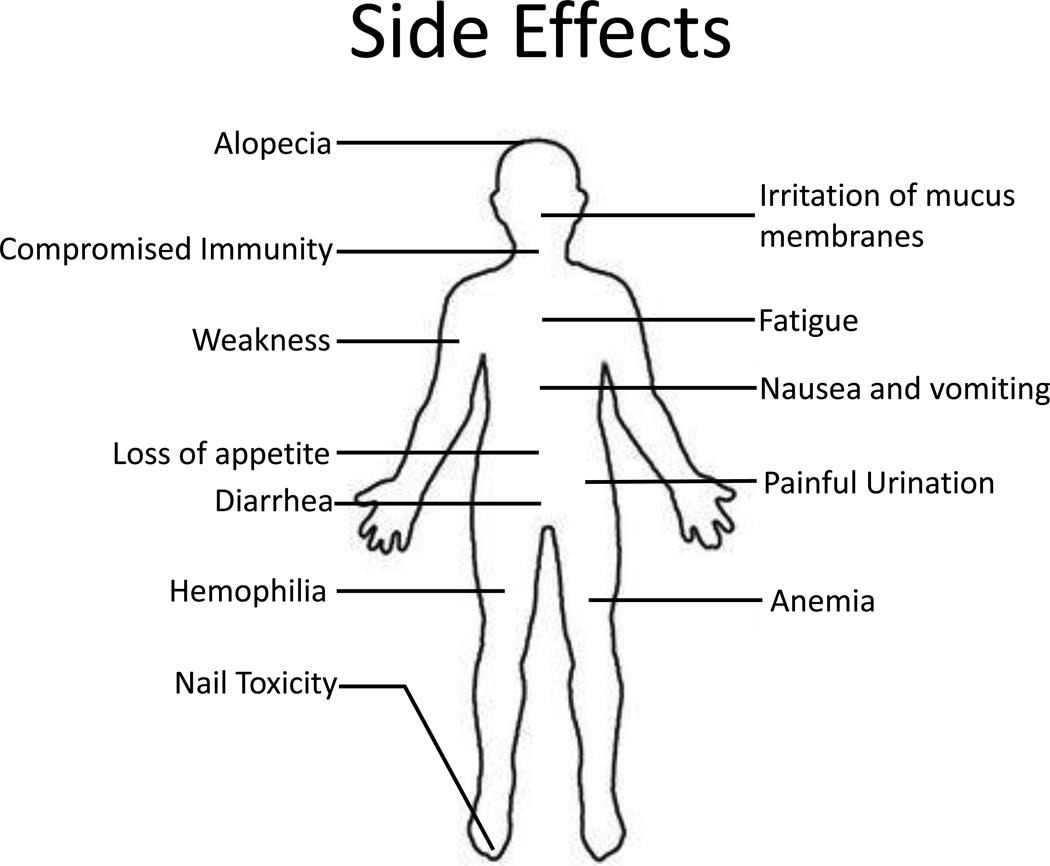

Though still our best tool against metastatic cancer, chemotherapy falls short as a cure for numerous reasons. Most prominent among them is the nonspecific toxicity associated with almost all chemotherapeutic treatments, which manifests itself through unwanted side effects including hair loss, nausea and vomiting, anemia, fatigue, increased bruising, immunodeficiency, loss of appetite, dyspepsia, irritation of the mucous membranes of the eye, nose and throat, rashes, urinary problems, and weight change (see Figure 2) [6]. This toxicity may pose a genuine danger to the life of the patient and often limits the dose which can be administered [7]. Chemotherapy treatments are also vulnerable to the development of multidrug resistance (MDR) in the target tumor, which often occurs in relapsed tumors [8]. Any revolutionary technology to treat cancer would have to rectify these shortcomings and effectively kill cancer cells without damaging healthy cells while preventing or overcoming resistant relapses.

Figure 2. Chemotherapy side effects.

Within minutes of intravascular administration, drugs and nanoparticles are thoroughly mixed in the circulatory system and distribute throughout the body. Wherever the drug comes in contact with healthy tissues non-specific toxicity will result causing unpleasant side effects. These side effects can be severe enough to limit the drug dosage and treatment effectiveness.

1.2. The promise of nanomedicine

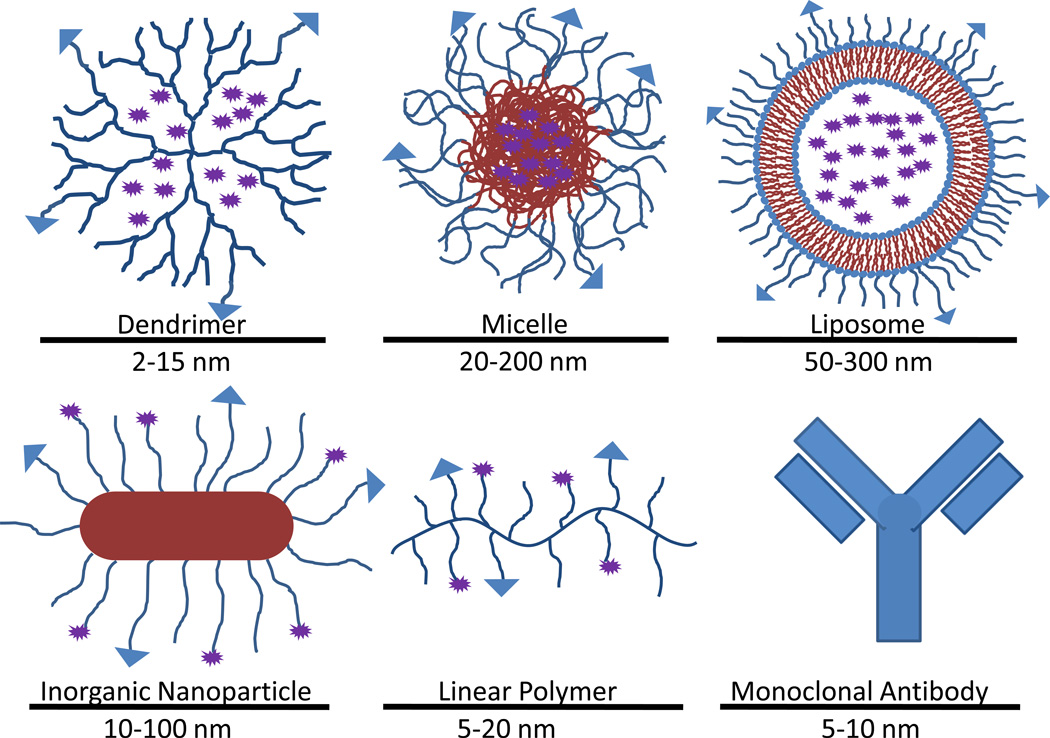

Nanotechnology is regarded as one of the most promising tools to surpass traditional chemotherapy as a front-line cancer treatment. Nano-sized drug carriers offer a versatile platform to which many useful functionalities can be added to improve the specificity and effectiveness of treatment (see Figure 3). Drug carriers can be designed to overcome many of the mechanisms conferring drug resistance to MDR cancers [9]. They can also be modified to improve specificity to tumors, thus limiting the drug exposure of healthy tissue and reducing side effects. Simultaneous diagnostic capability can also be added to aid doctors in making informed decisions regarding treatment [10].

Figure 3. Classes of nanoparticles in cancer therapy.

Nanoparticles come in a large variety of forms and a broad range of sizes. One of the chief advantages of nanoparticles is the ease with which it can be modified to carry drugs, targeting vectors and imaging agents.

However, 20 years of intensive research into nanomedicine has failed to translate into clinically successful cancer treatments. With the exception of monoclonal antibodies, only a few FDA approved nanotherapies exist today, and all of these are very simple in concept and design, not reflecting the complexity commonly seen in literature [11]. The gap between the promise of nanomedicine and the results seen in the clinic indicate a flaw either in concept or in implementation. Research groups around the world have developed countless complex and innovative nanoparticles [10, 12]. These particles are often tailored to accomplish a few very specific functions, such as enhancing cellular uptake or prolonging blood circulation. Tests in petri dish or small animal models often show impressive results but correlate poorly with clinical tumors.

1.3. Challenges of drug delivery

One explanation for the failures of drug delivery may be a gap in the prevailing conceptual framework guiding nanocarrier design. Before a drug can take action inside a cell it must complete an extensive journey [13]. The journey begins with the injection of the drug carrier into the bloodstream and continues through stages of circulation, extravasation, accumulation, distribution, endocytosis, endosomal escape, intracellular localization and action. Most nanoparticles specialize in one or two of these stages, but each is critical to the overall success of the therapy [14, 15]. Even targeted nanoparticles largely end up in organs other than the tumor. Twenty-four hours after injection the vast majority of nanoparticles are sequestered in the liver, spleen, kidneys and skin [16, 17]. Any drug localized away from the tumor can be considered to be a poison rather than a cure; this is due to the inevitable damage to healthy tissues.

Intratumoral drug accumulation and distribution may be the single most important challenge to future nanoparticle design. New nanocarriers must be designed with an understanding and due consideration of all stages of drug delivery. In some cases this may require a paradigm shift in the way we conceive the interactions between the drug carrier and the surrounding environment, opening new strategies such as the modification of the tumor microenvironment to make it more amenable to drug delivery [18, 19]. Successful new designs to improve drug distribution may relieve a major roadblock to bringing more nanotherapies to the market.

2. Circulation and tumor targeting

Most cancer treatments require that the nanoparticles be administered intravascularly. Depending on the tumor type and degree of metastasis, the injection site can be quite far from the tumor, requiring the nanoparticle to travel through the circulatory system, perhaps many times, before it has the opportunity to see the tumor. Some of the particular dangers facing a nanoparticle in circulation include opsonization, uptake by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), extravasation into noncancerous tissue, hepatic clearance, and for some particles, renal clearance.

2.1. Blood contact and nanoparticle characterization

The high surface to volume ratio of nanoparticles creates very high surface energies, which can bestow them with unusual behaviors [20]. One of the most immediate consequences of the nanoparticle’s unusually high surface energy is the danger of aggregation which can occur before the carriers are even administered. Aggregation can significantly alter the particle size distribution which in turn can affect the biodistribution. To further complicate matters, the interaction between nanoparticles and the complex milieu of whole blood is poorly understood [21]. No known artificial surface has been shown to be completely inert in blood. Immediately after injection, blood proteins begin to adhere to the nanoparticle surface [22].

Thermodynamically unstable particles (liposomes, certain compositions of polymersomes and micelles) may be disrupted by blood borne proteins and lipids [23]. These adhered proteins will eventually form a corona around the nanoparticle which acts as a signal promoting macrophage engulfing and may also affect extravasation and cell uptake [20, 24].

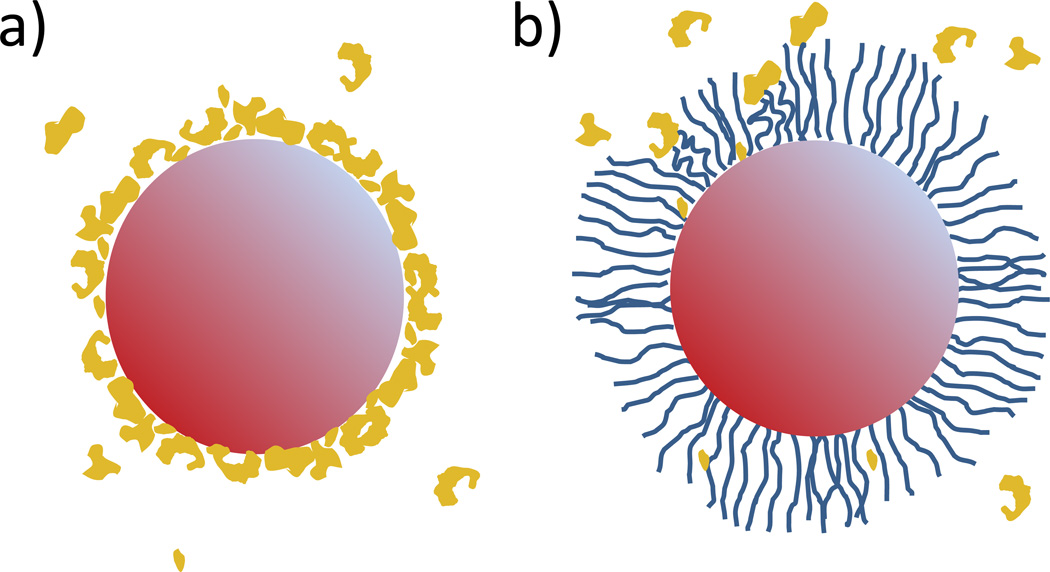

The kinetics of protein adsorption can be slowed by densely grafting hydrophilic polymer to the nanoparticle surface. The most common example of this surface modification is PEGylation, in which poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) is grafted onto the nanoparticle surface [25, 26]. The hydrophilic strands loosely extend into the surrounding aqueous media and create a brush-like barrier, which pushes away proteins before they can actually reach the nanoparticle surface. The graft density is critical to the effectiveness of a PEG coating in resisting protein adsorption. Most commonly, the graft density is too low, which leaves regions of the nanoparticle exposed for binding [24]. If the graft density were too high, the PEG can become too constrained and could no longer push adsorbing proteins away, instead becoming a new surface onto which proteins can directly adhere. However, even an optimal graft density will not eliminate protein adsorption but can merely slow it (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Protein adsorption onto nanoparticle.

(a) PEGylation of nanoparticles helps to slow the adsorption of proteins to the nanoparticle surface. The exposed surface of a non-PEGylated nanoparticle quickly develops a protein corona. The opsonized surface then promotes phagocytosis by MPS cells leading to rapid clearance of the nanoparticles. (b) The hydrophilic polymers grafted onto the nanoparticle form a brush-like barrier that repels most proteins before it can bind to the surface and thus significantly slows the clearance of the nanoparticles.

2.2. Targeting as a misnomer

Almost without exception, nanoparticles reach their site of action by purely passive processes. Belying this fact is the common term “targeting” as applied to drug delivery, which can easily call to mind images of a guided missile, acquiring and actively pursuing its mark under its own power. In reality, the drug is carried throughout the body by the circulatory system, and at best may differentially accumulate in the location of interest by passive means [27]. Within minutes of administration, nanoparticles are thoroughly mixed in circulation and carried indiscriminately to nearly every region of the body. Because the average clinical tumor is only a tiny fraction of the total weight and volume of a patient, the tumor receives a very small portion of cardiac output, meaning a given nanoparticle may have to circulate many times before it will even encounter the tumor site. Of the nanoparticles that encounter the tumor only some will diffuse into it; the rest will pass through and back into circulation. PEGylated nanoparticles can remain in circulation for up to several days after administration [28]. Unmodified nanoparticles, in contrast, may be cleared within minutes to an hour depending mostly on size and shape.

Even long-circulating nanoparticles are cleared from circulation by a variety of processes. The MPS, also known as the reticular-endothelial system (RES), is composed of specialized macrophages present in most tissues in the body but especially prevalent in the spleen, liver, skin, gut and thymus [29]. MPS uptake is enhanced by opsonized proteins, thus PEGylation can greatly reduce the rate of MPS clearance [24]. Nanoparticles may also be removed from circulation by extravasation into various tissues. Extravasation favors preferential accumulation in tumor tissue due to its enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) physiology (discussed in the next section), but is also common in the skin and liver due to the large size of these organs and particular vascular structures, such as sinusoid in the liver. Accumulation in the liver is particularly high, indicative of its role in detoxifying and clearing blood. Most nanoparticles are designed to be large enough to avoid renal filtration and clearance, but the kidney receives 22% of cardiac output and can consequently collect a large quantity of nanoparticles in the tissue [27]. Thus the vast majority of even the best designed “targeted” nanoparticles will ultimately reside in tissues other than the tumor tissue.

Prolonged exposure to the nanoparticles, especially in MPS organs where they become more concentrated, can raise biocompatibility concerns. In addition to cell damage caused by the cytotoxic drug cargo, the nanoparticles themselves may cause cell damage depending on the type. Inorganic nanoparticles, such as gold or iron oxide particles, are particularly problematic because they are very slow to clear out of the body [30]. Though most studies indicate that these particles do not cause biocompatibility problems in the short term, the effects of chronic exposure have not been adequately studied [30–33]. PEGylation reduces the toxicity of nanoparticles by minimizing the interaction between the high energy nanoparticle surface and the cell membrane, which can lead to disruption of the lipid bilayer [34]. Organic nanoparticles, such as liposomes, micelles and polymersomes, are much more readily degraded in the body, making chronic toxicity less of a concern. The primary concern regarding these nanoparticles is the metabolites formed during the degradation process [35]. Nanotoxicology is a separate subject within nanomedcine and there are many review articles available on the subject [36, 37].

2.3. EPR

Much of the optimism surrounding cancer nanotherapies is due to the EPR effect. Given sufficient circulation time, nanoparticles should accumulate preferentially in the tumor via EPR. This should result in a much higher relative accumulation to the site of interest, thus increasing efficacy while reducing damage to surrounding tissue [38]. The increased anti-tumor efficacy due to EPR will be referred to here as the EPR effect. EPR was discovered by Dr. Hiroshi Maeda in the 1980s when working with polystyrene-co-maleic acid conjugated neocarzinostatin (SMANCS) system in murine tumor models. The SMANCS/Lipiodol system was found to accumulate preferentially in solid hepatocellular carcinoma [39]. This is thought to be due to the leaky and disorganized nature of the blood vessels which allow large particles to escape from the blood vessels where the tight junctions between the endothelial cells of normal vasculature are too small to pass through. Retention occurs because of the tumor’s dysfunctional or collapsed lymph vessels, preventing proper drainage [40]. The unique vascular physiology of solid tumors can thus be exploited to create more effective therapies by simply packaging drugs in carriers too large to exit most normal vasculature, but small enough to pass through tumor fenestrae [41].

Whereas the EPR effect has been well documented in small animal models, clinical data is less clear. Some studies have tracked radiolabeled nanoparticles in human subjects and found some evidence of preferential accumulation in human tumors, though the strength of the effect is highly heterogeneous [42, 43]. Unfortunately, targeted drug carrier formulations have almost uniformly failed to produce improved efficacy in the clinic, in spite of tremendously successful preclinical results [44]. It is possible that the models being used to study EPR in laboratory studies are not sufficiently accurate and require reconsideration. While helpful in designing and screening new drug formulations and carriers, these models differ from clinical tumors enough that experimental results should be analyzed in context of these shortcomings. Animal tumors (specifically murine models) differ from human cancers in many respects including the rate of development, the size relative to host, metabolic rates and host lifespan.

The rate at which a tumor develops may have a large impact on the level of organization within that tissue. Time restraints on research and preclinical studies generally necessitate that murine tumor models be inoculated and fully developed very quickly. This is often done by injecting a large quantity of aggressive tumor cells into the model, then waiting for a few weeks to a few months for a tumor to grow to a sufficient size for experiments to proceed [45]. This extreme rate of growth results in very rapid angiogenesis leading to unusually disorganized vascular walls amenable to EPR. Some studies have shown that slowing the rate of blood vessel development using anti-angiogenic factors may create more normal vessels that are less permeable to large particles [46]. Unlike artificially induced animal tumors, human tumors can take decades to develop, giving time for a more controlled angiogenic process [47].

Animal tumors are often grown to more than 10% of the animal’s total body weight before treatment is administered [48]. The volume of an equivalent tumor in a 70 kg human would be the size of a basketball. Real human tumors are generally much smaller ranging from a few millimeters to a few centimeters at time of diagnosis and treatment [49]. Extravasation into a tumor requires first that a nanoparticle circulate through the tissue vasculature. This is exponentially less likely to happen in a 2 cm clinical tumor comprising 0.005% of the human body weight than a tumor of the same size comprising 10% of the mouse body weight. A given particle would need to circulate more than 10 days to have a 50% chance of encountering a tumor, but would only need 6 seconds to have the same probability of encountering an equivalent tumor in a mouse (see Appendix 1). Thus a drug carrier is much more likely to encounter and enter into a murine tumor via EPR than a human tumor.

Not only is the tumor biology between mice and humans different but the overall biological differences between the two are also significant and relevant. A mouse’s metabolism is much faster than a human’s. This allows for much more aggressive dosing regimens to be followed for mice than humans. Mice are generally sacrificed at the end of a study that has lasted only a few months making it impossible to observe relapses or slow growing metastases.

3. Extravasation determinants

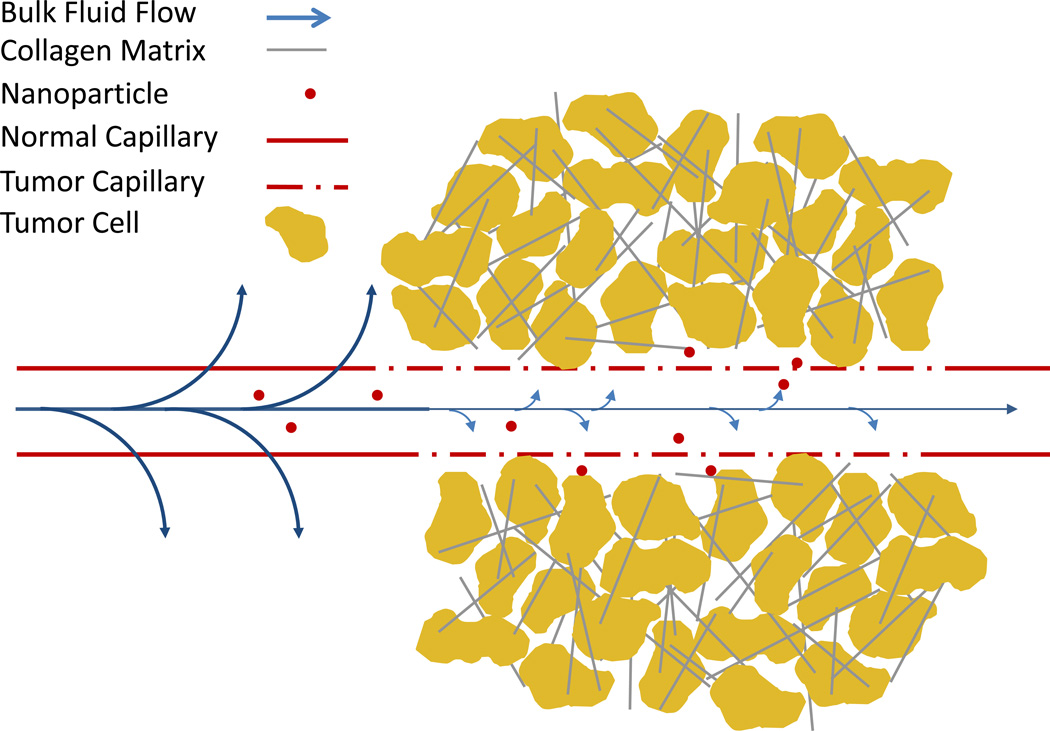

Nanoparticles that encounter the tumor while in circulation must exit the tumor blood vessel and enter the tumor interstitial space to continue the journey to the site of action. A particle could theoretically transition out of a capillary in several ways. EPR suggests that the dominant mechanism is diffusion out of the large tumor fenestrae, possibly aided by pressure gradients across the capillary wall driving bulk flow into the tumor. Some particles may also be actively transported across the capillary wall via transcytosis. Extravasation may be inhibited by elevated interstitial fluid pressure, which limits bulk flow, and tumor saturation (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Barriers to extravasation.

Extravasation from the tumor vasculature mostly occurs through the unusually large openings in the tumor vasculature, but is inhibited by several aspects of tumor physiology. High interstitial fluid pressure greatly reduces the driving force for bulk flow which can carry material out of the blood cell in healthy tissue. The dense collagen matrix and tumor cells can also trap nanoparticles as they diffuse out of the capillary preventing extravasation of subsequent particles.

3.1. Elevated interstitial tumor pressure (IFP)

The high IFP seen in most tumors can eliminate the driving forces would normally assist nanoparticle extravasation. In normal tissues, the transfer of oxygen, nutrients and waste into and out of the tissue is driven by Starling forces that drive bulk flows across the capillary walls [50]. The circulatory system is like a closed pipeline motivated by a central pump (the heart) creating a higher pressure within the system. This creates a hydrostatic pressure which tends to push fluid outward. The tight junctions of the blood vessels allow salts and small molecules to pass through freely, but macromolecules, such as proteins, are retained in the blood stream. Most interstitial fluid has a much lower concentration of large solutes than blood giving the blood a higher osmotic potential thus creating an osmotic force pushing fluid into the vessel. The hydrostatic and osmotic forces are balanced such that the arterial side of the capillary has a net outward flow, carrying oxygen and nutrients into the tissue, and the venous side experiences a slight inward flow, removing waste from the tissue. The low interstitial pressure in normal tissue is further enforced by the lymphatic system which carries excess fluid out of the tissue and back to the heart for recirculation. If the lymphatic system is dysfunctional or not able to keep up with the fluid intake into the tissue , edema develops to maintain low IFP by expanding the tissue volume [51].

The balance of Starling forces is severely disrupted in most tumor tissues. The large fenestrae that allow the extravasation of large nanoparticles into the interstitial space also fail to prevent the extravasation of proteins and other large solutes [52]. The resulting equality of solutes both inside and outside the capillary negates the driving force which pushes fluid back into the capillary. The lymph vessels of most tumors are also collapsed due to compressive solid stress (i.e. the rapidly dividing cells are packed so tightly so as to squeeze and destroy the delicate lymph vessels in the tissue) [53]. The dense, highly cross-linked extracellular matrix (ECM) of most tumors is unable to expand sufficiently to relieve the interstitial pressure by edema and reduces hydraulic flow to the tumor periphery. Depending on the relative severity of these factors, many tumors have interstitial fluid pressures which can approach the microvascular pressure feeding it, eliminating the bulk flows which aid extravasation in normal vasculature [54, 55].

Without the aid of bulk flow to drive extravasation nanoparticles must encounter and pass through the large but sometimes infrequent fenestrae, primarily via random walk diffusion [56]. The task may be made more difficult by the sluggish and intermittent flow commonly found in the tumor vasculature that may inhibit blood flow and drug delivery to large portions of the tumor [57]. In the absence of bulk flow out of the tumor, those particles that do extravasate out of the vasculature are nearly as likely to diffuse back into the capillary as to diffuse deeper into the tissue.

Elevated tumor IFP is highly intertwined with other aspects of tumor biology. The signals promoting rapid angiogenesis are thought to be largely regulated by tumor associated macrophages [58]. Blocking pro-angiogenic factors, either by targeting the source cells or directly, has been promoted as a strategy to normalize the vasculature and reduce IFP (though with the potential tradeoff of shrinking the fenestration window through which nanoparticles may extravasate) [46]. Reducing the collagen density in the tumor has also been shown to reduce IFP, likely by increasing hydraulic conductivity [59].

3.2. Tumor saturation

Chemotherapy is a delicate balancing act between bringing sufficient toxicity to bear against a cancer, without killing or permanently harming the patient. Any treatment which can tip the scales in favor of either or both of these objectives can be of significant benefit to cancer therapy in general. A recent German clinical trial used plasmapheresis to filter circulating doxorubicin-containing Doxil® nanoparticles from the blood approximately two days after administration. The researchers reported that the group that received filtering experienced fewer side effects without compromising efficacy, indicating that the initial hours of drug circulation contribute more to tumor toxicity than later hours [60].

One possible explanation for this phenomenon is tumor saturation. Large nanoparticles extravasate into the intracellular space just outside of a blood vessel and are unable to diffuse far beyond that. As a result they occupy critical space just outside of the capillary fenestrations and block the extravasation of other nanoparticles. This phenomenon would provide a two-phase extravasation profile where at first the flux across the capillary wall would be flow limited and relatively fast. Then as the basement membrane outside the capillary wall became saturated, the extravasation would become diffusion limited as particles would have to either degrade or diffuse deeper into the tumor to clear room for more particles.

4. Intratumoral distribution

A treatment regime should ideally eradicate the tumor entirely, or at least sufficiently to allow natural processes and adjuvant therapy to finish what is left to prevent relapse. However, tumor vasculature is not evenly distributed through the entire tissue [61], necessitating that large portions of the tumor be accessed by diffusion, sometimes over very long distances. Aside from distance, diffusion to distal regions of the tumor is inhibited by densely packed cells, a dense extracellular matrix and interactions between the particles and the environment.

4.1. Blood vessel distribution

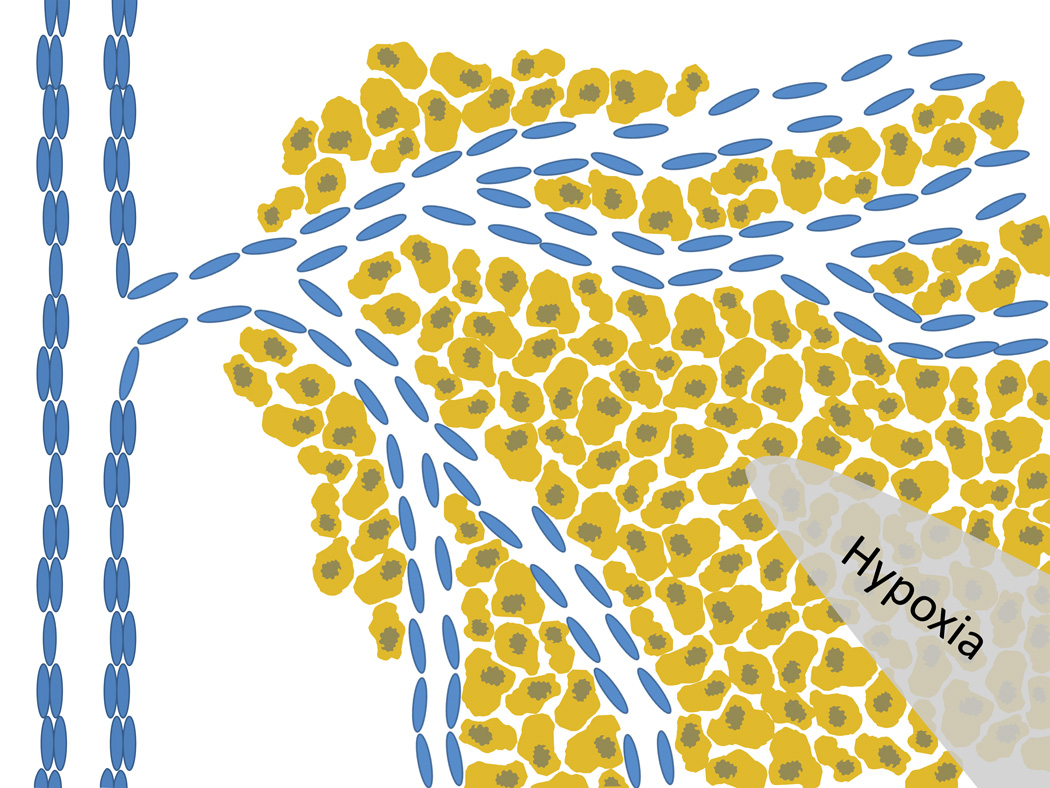

The uneven distribution of blood vessels can leave many regions of a tumor far from any blood source and largely inaccessible to nanoparticles (see Figure 6). The blood vessel distribution in a tumor largely depends upon the growth rate of the tumor. The native tissue hosting the tumor is already well-vascularized, but as the tumor overgrows the healthy tissue the compressive solid stress from the rapidly dividing cells in a confined area often crushes the healthy blood vessels [53]. Most vessels which feed the tumor are generated after it has established itself. Once a tumor has grown larger than approximately 1mm in diameter, cells toward the center of the mass can no longer be supplied by diffusion, leaving them severely hypoxic and possibly even necrotic at the core. Hypoxic cells release pro-angiogenic factors which stimulate endothelial cells from nearby blood vessels to rapidly divide and form hastily constructed blood vessels to supply the tumor. Because these vessels form after the tumor has already formed a thick mass, the tumor tends to be most heavily vascularized near the periphery, leaving many cells far from the blood vessels and thus inaccessible [62].

Figure 6. Capillary distribution.

Recruitment of capillaries from nearby blood vessels leaves the tumor periphery better vascularized than the core. The large distance from the capillary to the center of the tumor causes hypoxic conditions in the core and necessitates nanoparticles to diffuse large distances to reach all areas of a tumor.

The pressure on the interior of the tumor tends to be nearly uniform until very close to the tumor’s edge [63]. Near the edge, where the high pressure of the tumor tissue interfaces with the much lower pressure of the surrounding healthy tissue, a pressure gradient exists that can drive bulk fluid flow to the outside of the tumor. The net result is a slight convective flow from the tumor blood vessels to the tumor periphery posing a small force working against the particle diffusion toward the tumor core [64].

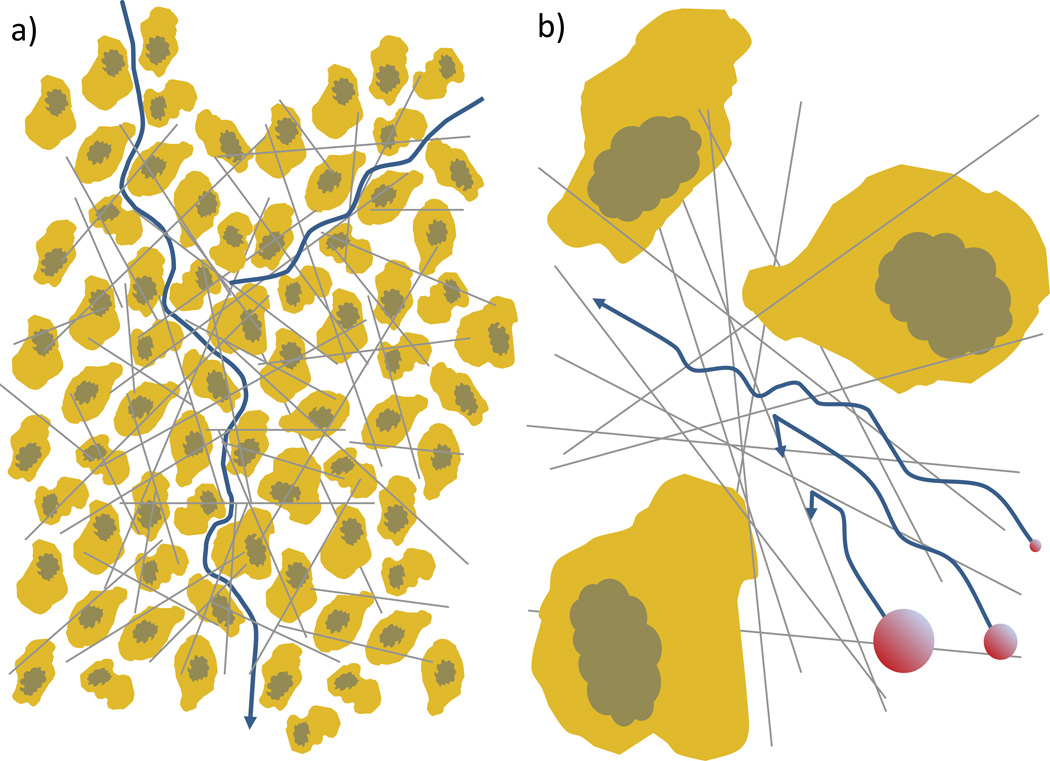

4.2. Barriers to diffusion

The diffusion of nanoparticles from the capillary to interior cells can be made even more difficult by the presence of extracellular matrix (ECM) and tightly packed cells (see Figure 7). The extracellular matrix of tumor tissue is often more dense and highly cross-linked than in healthy tissues. The tumor ECM can be highly heterogeneous and thus affect particle distribution in very different ways depending on location. The degree of resistance to particle diffusion varies depending on the collagen density, cross-linking density and collagen stiffness [65, 66]. The ratio of particle diameter to mesh size plays a critical role in the ECM resistivity, with the particle being hindered to a greater and greater degree as the particle size approaches the local mesh size until the particle becomes completely immobilized. Particles are also unlikely to be completely inert toward the ECM [67, 68]. Interactions with ECM components will further hinder particle motion above the physical barrier that the ECM’s collagen network poses [69].

Figure 7. Diffusion barriers.

a) The architecture of a tumor can severely limit particle diffusion through the tissue. The densely packed cells increase the total path length the particle must travel to cover a linear distance, which can significantly impact the effective diffusion. b) The collagen matrix barrier becomes increasingly important as the particle size approaches or exceeds the matrix mesh size which ranges between 20–40 nanometers in solid tumors. Particles larger than the mesh size can be prevented from diffusing from the matrix entirely, those near the mesh size can be significantly hindered, and small particles can pass through relatively uninhibited.

Due to the cancer cell’s rapid division within a restricted space, the cell density inside a tumor can be extremely high, approaching or even exceeding 60% [70]. This is approximately the density of close packed solid spheres, so most cells are going to be bounded by and in contact with neighboring cells on all sides [71]. Cells are also very large relative to the nanoparticles which must diffuse between them, ultimately creating a highly tortuous pathway through which particles must diffuse. To give perspective, if a nanoparticle were the size of a 1.9 meter man, tumor cells could be represented by an endless matrix of tightly packed football stadiums. Put more rigorously, if the cell arrangement in to tumor is assumed to be equivalent to a packed bed of solid spheres with a void fraction of 0.35 [70], the tortuosity (the minimum path length in the presence of obstacles divided by the straight line between points) of the hydraulic path through that media is expected to be approximately 1.6 [72]. This translates into a 2.5 fold decrease in the effective diffusivity compared to acellular diffusion. Many nanoparticles are also designed to interact with specific receptors on the cell surface which can create a binding-site barrier in which the nanoparticle interacts with the first few lines of cells closest to the blood vessel and is unable to move deeper into the tumor interior [73]. This barrier can also be formidable due to the large surface area of the tightly packed cells.

These barriers only serve to exacerbate the already daunting distance barrier blocking drug access to cells in the tumor core. In plasma, a 70 nm diameter particle would require an average of 20 minutes to diffuse 200 µm, the average distance from a capillary in which hypoxic conditions become severe. Assuming no chemical interactions, the physical barriers of the collagen matrix of the ECM and the tightly packed cells would reduce the effective diffusivity 10-fold and increase the diffusion time to more than 3.5 hours (see Appendix 2). Chemical interactions between the particles and tumor components could decrease the particle diffusivity as much as several more orders of magnitude [69].

The diffusion barrier to nanoparticle delivery is largely inherent to the size of the drug carrier. Efforts to alleviate the drug distribution problem have focused largely on the modification of the tumor environment to reduce collagen density and lower IFP [59, 66]. Early studies delivered high doses of collagenases by intratumoral injection followed by intravascular drug delivery in mice [66, 74]. More recent experiments have demonstrated the possibility of systemic collagenase delivery [59, 75]. Clinical tumors are often not accessible or visible, making systemic intravascular delivery necessary in many cases. Systemic delivery of collagenases presents general toxicity concerns, particularly to delicate structures such as the lungs. The potential to promote metastasis by reducing the collagen barrier to cell movement in the tumor must also be addressed, but this strategy is still promising as a means to overcome one of the more intractable barriers to cancer nanotherapy.

4.3. Solid tumor as an organ

Tumors are not monolithic tissues with homogenous structures and cell types, but can be thought of as an organ whose sole purpose is growth, living as a parasite off the surrounding tissue. As with an organ, a tumor may contain a menagerie of cell types serving different roles in support of its function. These cell types may include epithelial cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, perivascular cells, mesenchymal stem cells and myriad immune cells in addition to the primary cancerous cell type [76]. Different cell types will naturally respond differently to drug exposure. These cell types do not divide as rapidly as the primary cancerous cells and will thus be less damaged by metabolism and division targeted drugs such as doxorubicin or paclitaxel. Some cell types, such as macrophages may have a direct effect on drug delivery by engulfing nanoparticles and either sequestering or facilitating the spread of their cargo [77, 78].

Support cells that play essential roles within the tumor can make inviting targets for alternative cancer therapies. Many therapies target vascular cells and associated factors in hopes of cutting off the tumor’s supply of oxygen and nutrients to slow its growth [79]. The most common treatment targeting the tumor vasculature seeks to slow or stop angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels, by targeting various pro-angiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Other strategies involve attacking the tumor endothelial cells directly, though achieving sufficient specificity to avoid widespread toxicity can be a challenge [80]. These treatments may actually help to normalize the tumor vasculature, which alleviates the high IFP and aids small molecule drug delivery to the tumor tissue [46]. Tumor associated macrophages (TAMs), which are associated with metastasis and angiogenesis, are also a popular target for cancer treatment [81]. In both cases, targeting support cells alleviates the intratumoral distribution problem; the vasculature is the first thing encountered by a drug carrier once it reaches the tumor and macrophages are mobile and able to come to the drug, if necessary. Unfortunately, neither therapy can actually kill a tumor, but rather slows or suppresses it. In consequence, these treatments are usually combined with traditional chemotherapeutics aimed at the primary tumor cells [79].

5. Cell Uptake

For nanoparticles able to penetrate the tumor and reach a target tumor cell, the journey is not yet over. The nanoparticles must next deliver their cargo across the cell membrane and then safely deliver it to the drug’s site of action, whether in the cytoplasm, the nucleus or some other organelle. A large portion of nanocarrier delivery strategies are designed specifically to promote cell uptake.

5.1. Cell Membrane

The cell membrane can be a formidable barrier to drug delivery, whether nanotechnology is employed or not. While small, hydrophobic molecules can easily diffuse into the membrane [82], large or hydrophilic particles, such as nanoparticles, cannot passively diffuse through the lipid bilayer membrane and instead must enter via other mechanisms [83, 84]. While this limits the access of a nanoparticle to the cell interior, clever design can turn the active uptake requirement into an advantage.

Most chemotherapeutic drugs, whether in free or solubilized form, can pass through the cell membrane by diffusion. However, over the course of treatment many cancers can acquire resistance to free drug treatment [85]. The most common mechanism of acquired drug resistance is the overexpression of membrane bound pumps, usually P-glycoprotein (Pgp), which actively removes toxins, such as chemotherapeutic drugs, out of the cell [86]. Pgp induced resistance can render a wide variety of free drugs largely ineffective except at very high and potentially toxic concentrations. Highly resistant cells can maintain a four-to-six fold difference in concentration across the membrane [87]. Some nanoparticle formulations are designed to disassociate in the tumor interstitium, releasing the drug to diffuse through the tumor and into the cell [88]. This strategy takes advantage of the superior diffusivity of free drug molecules to enhance drug delivery to the interior portions of the tumor, while still theoretically taking advantage of EPR to improve tumor accumulation. The free drug also has immediate access to the cell interior by diffusion. The downside to this strategy rests in vulnerability to being rendered ineffective in drug resistant cells.

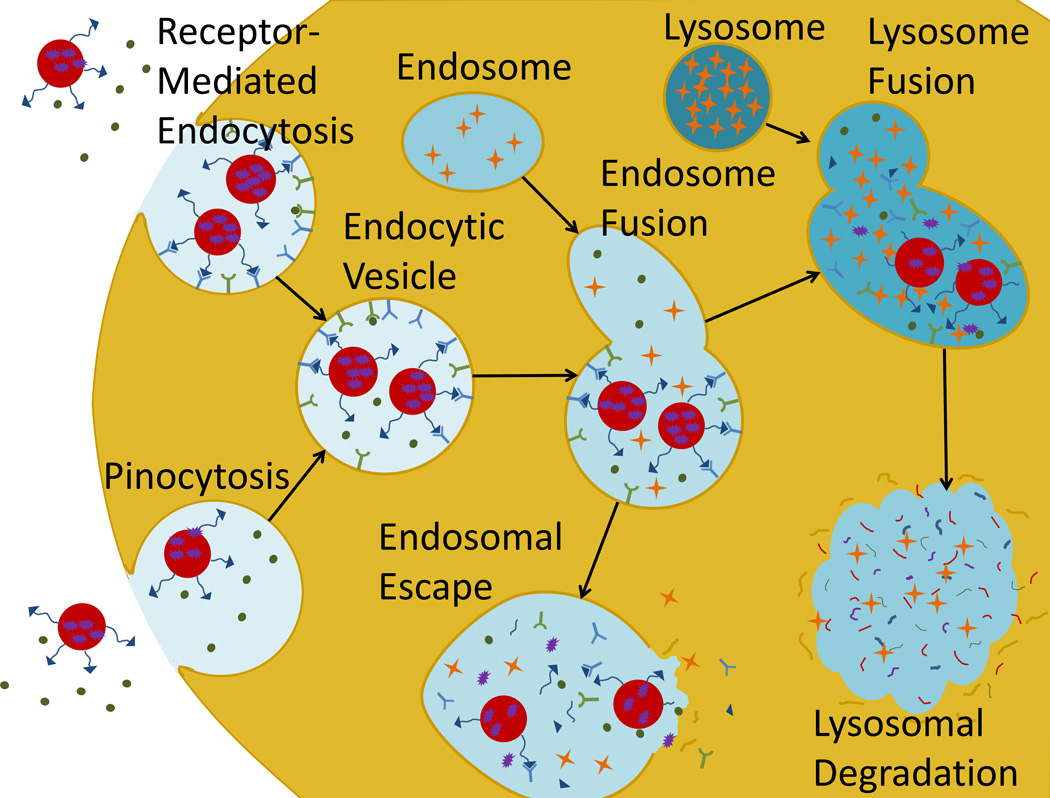

Many delivery strategies aim to bring nanoparticles into the interior of the cell intact. This requires the particles to be internalized via an active uptake mechanism such as receptor-mediated endocytosis or pinocytosis [82]. Pinocytosis is a relatively haphazard way for cells to sample their surroundings by enveloping large quantities of surrounding fluid. Receptor-mediated endocytosis is a more controlled method for bringing specific substances into the cell and is generally governed by receptor-ligand interactions at the cell surface. Increasing the strength and probability of these interactions at the tumor cell has become a popular strategy to increase cell uptake at the tumor site [89]. The prevailing wisdom has been that receptor-ligand targeting also enhances tumor localization but this claim is controversial [90–93]. Targeting moieties cannot target a tumor in the sense of actively seeking out its receptor. Instead targeted nanoparticles may approach a receptor by random diffusion and short range interactions can bring the two together once they have come within a few nanometers of each other [94].

Many targeted drug formulations have been reported in literature, but in spite of abundant success in preclinical investigations, none currently have clinical approval and only four are undergoing clinical trials, three in phase I and one in phase II (a number of monoclonal antibodies have FDA approval, but these act directly on the target receptor without requiring internalization) [95]. Two-dimensional cell culture models are popular for showing enhanced uptake for targeted nanoparticles [96]. However, these models bring the drug into close contact with the targeted receptor, have no delivery barriers, generally test a genetically homogenous cell population, and have a paucity of potentially competing receptors as would be found in the body. Even animal tumor models, in addition to the problems discussed previously regarding EPR, generally lack the genetic diversity needed to simulate clinical tumors [97]. Evidence is insufficient at this point to predict the efficacy of receptor-ligand targeting in the clinical setting.

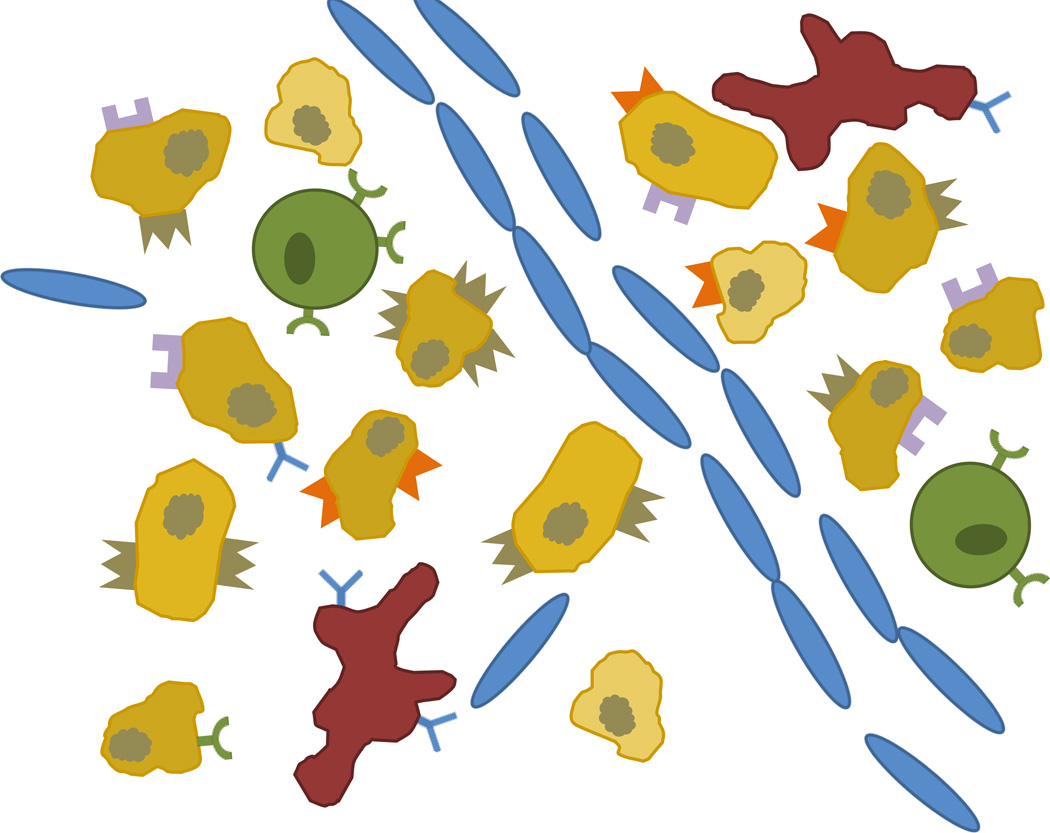

5.2. Intercellular phenotypic diversity

Tumor heterogeneity is not limited to the diversity of cell types and structure, but also extends to genetic diversity within the primary tumor cell line (see Figure 8) [98]. The rapid and under-regulated cell division characteristic of cancer can cause broad genetic diversity across cancer cells in the same tumor. This can result in varying levels of surface markers available for receptor-ligand targeting and various levels of drug resistance within the same tissue (see Figure 8). Both of these phenomena may influence the way we approach treatment.

Figure 8. Cell heterogeneity in tumors.

Tumors contain many cell types including macrophages, stem cells, endothelial cells and tumor cells. Cells may also bear a variety of different receptors expressed in varying amounts and will have other genotypic differences which may affect drug sensitivity (represented as different shading in tumor cells).

Variable expression of surface proteins can have a huge influence on the effectiveness of receptor-ligand targeting strategies. These strategies often depend on particular targets considered to be overexpressed on the tumor surface. A classic example is the HER2 receptor which is overexpressed in a minority of breast cancer tumors. Herceptin® is a monoclonal antibody designed to bind to and block this receptor and is clinically approved to treat tumors that strongly express HER2. The immunohistochemistry (IHC) scoring method was established to determine what patients qualify for treatment with Herceptin®. While scoring guidelines can vary somewhat, conservative interpretations consider a patient to be HER2 positive if 10% or more of tumor cells show strong staining and strongly positive (very likely to benefit from Herceptin® treatment) if 30% or more of cells stain for HER2 [99]. Herceptin® is considered one of the great success stories of targeted cancer therapy, yet the best case scenarios have scarcely a third of cells strongly expressing the target. Other receptors may be expressed even more tentatively.

Cells may also express varying levels of drug resistance within a tumor, setting up a dangerous Darwinian trap for partially effective treatments. The combined effect of the drug delivery barriers discussed so far is to limit the amount of drug that can be brought to bear against a tumor without doing severe harm to a patient [100]. Uneven or nonlethal drug doses risk selecting for the most dangerous and resistant cancer cells. Nearly 80% of nonresectable tumors become resistant to at least one therapy over the course of treatment [85]. This resistance often occurs in a tumor that has relapsed after an initially successful treatment. Improving drug distribution could have a revolutionary impact on cancer therapies by limiting the recurrence of more aggressive, drug resistant tumors.

5.3. Endosomal escape

Most active endocytotic pathways direct the endocytosed material through the lysosome for cellular digestion before it is allowed access to the cytoplasm (see Figure 9). The cellular digestion process serves the dual purpose of breaking down any potentially dangerous pathogens before they can access the cell and freeing material for use in cell processes. During endocytosis, a portion of the outer membrane is pinched off inside the cell to form a vesicle containing the endocytosed material which is fused with interior vesicles to form a mildly degradative endosome. These vesicles eventually fuse with the lysosome, which is highly acidic and filled with powerful proteases to break down any material contained inside [101, 102]. The endosome is generally capable of degrading organic nanoparticles and even rendering drugs inert [103]. If the nanoparticle can escape the endocytic vesicles during the endosomal phase, the lysosomal degradation of the carrier and drug may be avoided.

Figure 9. Active cell uptake.

The major methods of nanoparticle cell uptake are receptor mediated endocytosis and pinocytosis. Both draw the particles into interior vesicles which eventually fuse with lysosomes to undergo cellular digestions which can neutralize some or all of the drug. Releasing the drug from the endosome before the lysosomal phase can increase the availability of drug in the cytoplasm.

The proton sponge effect is a popular method to aid endosomal escape. The proton sponge effect works by sequestering excess protons, usually by a polymer such as polyethylenimine (PEI) which contains unsaturated amino groups. The buffering by the polymer causes additional counter ions and water to be pumped into the endosome which may eventually cause it to swell and rupture, releasing the contents directly into the cytoplasm. This hypothesis has yet to be proven, but is a likely explanation for the improved transfection by PEI-bearing gene vectors [104]. An alternative strategy may involve simply allowing the nanoparticle to disassociate in the early endosomal phase, and hope sufficient time is allowed for the drug to diffuse out of the endosome and into the cytosol.

6. Intracellular localization

The final step in our journey is to bring the drug to its site of action within the cancer cell. The strategy for this step typically depends on the mechanism of the drug. Many drugs may begin to take effect immediately upon entering the cytoplasm. These include taxanes, which act on microtubules, and alkylating agents, which indiscriminately cross-link amino groups or nucleic acids. Some oligonucleotide therapies may also be effective in the cytoplasm such iRNA. Other drugs directly damage DNA or interfere with DNA replication and must enter the nucleus to be fully effective. These drugs must cross the nuclear membrane before they can take action.

Most small hydrophobic molecules are able to diffuse across the nuclear envelope as they can the cell membrane. Drug resistant cells can express Pgp in the nuclear envelope [105]. Larger molecules, such as nucleic acids used in gene therapy and peptides, must access the nucleus through the nuclear pore complex. Access to this complex can be highly regulated, but co-delivery of the drug with some compounds, such as dexamethasone, may aid access to the nucleus and thus the drug targets contained therein [106]. Actively dividing cells may also provide an opportunity for nuclear access during mitosis. During prophase the nuclear envelope is disassembled and the chromatids are exposed to the cytoplasm. Particles may then associate with the DNA before the nuclear envelope reassembles during telophase [107].

7. Conclusion: Cost benefit analysis of nanotechnology-based therapies

After surveying the significant obstacles to nanoparticle delivery, it seems reasonable to question whether these nanotherapies work at all. Doxil® and Abraxane® are currently the most successful nanotechnology-based treatments on the market. While preclinical studies of both formulations showed tremendous gains in efficacy over free drug formulations [108], phase III clinical trials showed only marginal improvements over existing therapies. In the case of Doxil® the efficacy gains were not even statistically significant and FDA approval was granted largely on the basis of its reduced cardiotoxicity [109, 110]. The efficacy gains seen in Abraxane® most likely are a result of elevated doses allowed by the reduction of toxicity (which was largely from the Cremaphor® EL—castor oil—used to solubilize the paclitaxel).

Doxil® and Abraxane® are relatively simple in design and ambition. The modest success of these formulations should give both hope and concern for the future of nanomedicine in cancer therapy. Why did these two commercial formulations show almost no increase in efficacy during clinical trials when preclinical studies were so promising? Why have more sophisticated nanotechnologies failed to show any benefit to patients in clinical trials? Can nanotechnology deliver the promised revolution in cancer therapy?

To be successful, future designs will have to leverage the natural advantages of nanoparticles as a drug delivery platform. The advantages of nanoparticles in drug delivery include its almost limitless versatility allowing the researcher to engineer particles with almost any imaginable characteristic. Size, shape, composition and surface chemistry can all be manipulated to improve circulation, distribution, specificity and cell uptake. Our ability to manufacture particles with the desired characteristic will improve with time, as will our understanding of what characteristics will optimize efficacy against a given tumor. At present, however, our understanding of how nanoparticles behave in the human body is extremely limited. Nanoparticles’ high surface energy and small size (relative to the researcher) make it difficult to understand their interaction with the complex and often hostile environment of the human body, and its large size (relative to small molecule drugs) severely limits intratumoral diffusion, and thus efficacy away from the tumor microvasculature.

In Homer’s telling of the great journey of Odysseus from Troy to his home in Ithica, Odysseus sails past the island of the Sirens, whose song is so irresistible that the crews who heard it invariably dashed their ships to pieces on the treacherous shoals of the island trying to reach the source of the music. Wanting to hear the song, Odysseus ordered his men to tie him securely to the mast so he could not jump overboard to certain death, while his crew stopped their ears with wax so they could sail by impervious to the danger. Odysseus did not sacrifice his true objective–finding his way home—to pursue the Sirens’ song. Nor can we abandon our objective of discovering new technologies to extend life and alleviate suffering, to pursue ever-more-complex designs that have little clinical relevance.

So is nanotechnology the way forward for cancer research or do the pitfalls outweigh the advantages? That is a question that may only be answerable in hindsight. But for the present, new drug carrier designs should be informed by an appreciation for the complexity of human and cancer biology, as well as a healthy respect for the ability of both to defend itself from foreign substances. Existing technologies, as well as those being developed in labs around the globe, are ingenious applications of an improved understanding of cancer biology and a testament to the desire to finding new solutions to combat the disease. Considering the journey of the cancer nanoparticle—from the injection site to the site of action—holistically, and seeking the simplest possible design that may complete that journey, may be the key to bringing more of these technologies into clinical relevance.

Highlights.

-

! !

No drug can be effective against cancer until it is successfully delivered from the administration site to its site of action within the tumor

-

! !

There are barriers to drug delivery at every level of drug distribution including systemic, tissue and cellular levels

-

! !

Current delivery strategies such as receptor-ligand targeting and EPR may not be effective in clinical tumors

-

! !

New drug carrier designs should be educated by an appreciation of the full scope of drug delivery barriers

Biographies

Dr. You Han Bae worked at University of Utah as a research assistant/associate professor until 1994 when he joined the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology (Korea) in 1994, and became a full professor in 1998. He re-joined the University of Utah as a full professor in 2002. His research interests include pH-sensitive micelles, multidrug resistance in tumors, tumor heterogeneity, intratumoral distribution, polymeric vectors for gene and protein delivery, and animal tumor models. He has published over 225 peer-reviewed scientific papers, book chapters and U.S. patents. He served the Controlled Release Society as a member of Board of Scientific Advisory, as Chair of the Young Investigator Award committee, and as a program co-Chair for the society’s 34th annual meeting at Long Beach, CA (2007). He is a co-chair of International Symposium on Recent Advances in Drug Delivery System, and is currently an associate editor for the Journal of Controlled Release.

Joseph Nichols received his B.S. in Chemical Engineering from Brigham Young University, and is currently a PhD student in the Bioengineering Department at the University of Utah. His research interests include tissue-level pharmacokinetic models and intratumoral drug distribution.

Appendix 1

This calculation is done using the binomial distribution

| Equation 1 |

Where (n choose k) is the function n!/(k! (n-k)!) and k is the number of successes in n trials. P is the probability of achieving k successes, and p is the probability of success in a given trial. For a human subject cardiac output is 5 L/min with a 5 L blood volume, indicating the blood circulates on average once per minute [50] and a mouse has an average blood volume of 2 mL and a cardiac output of 20 mL/min for an average of 10 circulations per minute [111]. The probability that a particle will encounter the tumor in a single round of circulation is assumed to be equivalent to the ratio of tumor to body mass and for a human and mouse is p=0.00005 and p=0.1 respectively.

Appendix 2

The diffusivity of a generic nanoparticle is estimated here by the Stokes-Einstein equation which relates the diffusion coefficient (Dab) to the hydrodynamic radius of the particle R, the viscosity of the surrounding fluid (η) and the heat energy present in the solution (kT).

| Equation 2 |

Hindered diffusion is calculated using the equation proposed by Pluen et al. which modifies the unhindered diffusivity by the effective tortuosity of the hindering materials [112].

| Equation 3 |

The value τ represents the effective tortuosity resulting from cellular obstacles or from the collagen matrix. Values for τ were derived differently for each obstacle. The tortuosity due to the dense cellular barrier (τcell) was estimated based on an empirical formula used to describe the hydraulic tortuosity of packed beds with void fraction (ε) of sand described by Sen et al. [72].

| Equation 4 |

No convenient mathematical representation of the tortuosity due to the collagen matrix could be found, so the value was estimated from a study conducted by Ramanujan et al. which measured diffusivity in a prepared collagen gel [65]. The largest particle used in the study was only 20 nm, so the effective tortuosity was conservatively estimated by selecting the highest effective tortuosity (the 20 nm particle) for the medium collagen density level and not attempting to extrapolate further.

The average time (t) required to diffuse a given distance (r) was calculated using the mean square displacement formula.

| Equation 5 |

These values are estimates meant to illustrate the barriers to diffusion and may vary wildly depending on the tumor type, composition and intratumoral location.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Farber S, Diamond LK. New Engl. J. Med. 1948;238:787–793. doi: 10.1056/NEJM194806032382301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viscomi S, Pastore G, Mosso ML, Teracini B, Madon E, Magnani C, et al. Haematol- Haematol J. 2003;88:974–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukherjee S. Emperor of All Maladies. New York, NY: Scribner; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2012. Atlanta, GA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azzoli CG, Baker S, Temin S, Pao W, Aliff T, Brahmer J, et al. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:6251–6266. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.5622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Cancer Society. Understanding Chemotherapy : A Guide for Patients and Families. Atlanta, GA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson P, Schlossman R, Jagannath S, Alsina M, Desikan R, Blood E, et al. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2004;79:875–882. doi: 10.4065/79.7.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Licht T, Fiebig HH, Bross KJ, Herrmann F, Berger DP, Shoemaker R, et al. Int. J. Cancer. 1991;49:630–637. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910490427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shapira A, Livney YD, Broxterman HJ, Assaraf YG. Drug Resist. Updates. 2011;14:150–163. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nasongkla N, Bey E, Ren J, Ai H, Khemtong C, Guthi JS, Chin S, et al. Nano Lett. 2006;6:2427–2430. doi: 10.1021/nl061412u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner V, Dullaart A, Bock A-K, Zweck A. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1211–1217. doi: 10.1038/nbt1006-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Min KH, Kim J-H, Bae SM, Shin H, Kim MS, Park S, et al. J. Controlled Release. 2010;144:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mikhail AS, Allen C. J. Controlled Release. 2009;138:214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alderden RA, Mellor HR, Modok S, Hall MD, Sutton SR, Newville MG, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:13400–13401. doi: 10.1021/ja076281t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee CM, Tannock IF. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:255. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao J, Chen K, Luong R, Bouley DM, Mao H, Qiao T, et al. Nano Lett. 2012;12:281–286. doi: 10.1021/nl203526f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang C, Qu G, Sun Y, Wu X, Yao Z, Guo Q, et al. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1233–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu M, Tannock IF. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:327–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingber DE. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2008;18:356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lundqvist M, Stigler J, Elia G, Lynch I, Cedervall T, Dawson KA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:14265–14270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall JB, Dobrovolskaia MA, Patri AK, McNeil SE. Nanomedicine. 2007;2:789–803. doi: 10.2217/17435889.2.6.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindman S, Lynch I, Thulin E, Nilsson H, Dawson KA, Linse S. Nano Lett. 2007;7:914–920. doi: 10.1021/nl062743+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tall AR. J. Lipid Res. 1980;21:354–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunath K, Harpe AV, Petersen H, Fischer D, Voigt K, Kissel T, et al. Pharm. Res. 2002;19:810–817. doi: 10.1023/a:1016152831963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Storm G, Belliot S, Daemenb T, Lasic DD. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 1995;17:31–48. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis SS. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15:217–224. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar R, Roy I, Ohulchanskky TY, Vathy LA, Bergey EJ, Sajjad M, et al. ACS Nano. 2010;4:699–708. doi: 10.1021/nn901146y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Owens DE, Peppas Na. Int. J. Pharm. 2006;307:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wittamer V, Bertrand JY, Gutschow PW, Traver D. Blood. 2011;117:7126–7135. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-321448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadauskas E, Danscher G, Stoltenberg M, Vogel U, Larsen A, Wallin H. Nanomedicine. 2009;5:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu J, Liong M, Li Z, Zink JI, Tamanoi F. Small. 2010;6:1794–1805. doi: 10.1002/smll.201000538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanini A, Schmitt A, Kacem K, Chau F, Ammar S, Gavard J. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011;6:787–794. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S17574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishimori H, Kondoh M, Isoda K, Tsunoda S-I, Tsutsumi Y, Yagi K. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2009;72:496–501. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pilloni M, Nicolas J, Marsaud V, Bouchemal K, Frongia F, Scano A, et al. Int. J. Pharm. 2010;401:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uhrich KE, Cannizzaro SM, Langer RS, Shakesheff KM. Chem. Rev. 1999;99:3181–3198. doi: 10.1021/cr940351u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garnett MC, Kallinteri P. Occ. Med. 2006;56:307–311. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kql052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oberdörster G. J. Intern. Med. 2010;267:89–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwon G, Suwa S, Yokoyama M, Okano T, Sakurai Y, Kataoka K. J. Controlled Release. 1994;29:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsumura Y, Maeda H. Cancer Res. 1986;46:6387–6392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maeda H, Sawa T, Konno T. J. Controlled Release. 2001;74:47–61. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00309-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maeda H, Seymour LW, Miyamoto Y. Bioconjugate Chem. 1992;3:351–362. doi: 10.1021/bc00017a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiner RE. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1996;23:745–751. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(96)00119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harrington K, Mohammadtaghi S. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001;7:243–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, Farokhzad OC, Margalit R, Langer R. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007;2:751–760. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jonkers J, Berns A. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:251–265. doi: 10.1038/nrc777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jain RK. Science. 2005;307:58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1104819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weinburg RA. The Biology of Cancer, Garland Science. New York, NY: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ozao-Choy J, Ma G, Kao J, Wang GX, Meseck M, Sung M, et al. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2514–2522. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carter CL, Allen C, Henson DE. Cancer. 1989;63:181–187. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890101)63:1<181::aid-cncr2820630129>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silverthorn DU. Human Physiology. Fourth Edition. San Francisco, CA: Pearson Education, Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parving HH, Hansen JM, Nielsen SL, Rossing N, Munck O, Lassen NA. New Engl. J. Med. 1979;301:460–465. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197908303010902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stohrer M, Boucher Y, Stangassinger M, Jain RK. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4251–4255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roose T, Netti Pa, Munn LL, Boucher Y, Jain RK. Microvasc. Res. 2003;66:204–212. doi: 10.1016/s0026-2862(03)00057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boucher Y, Jain RK. Cancer Res. 1992;52:5110–5114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boucher Y, Salehi H, Witwer B, Harsh GR, Jain RK. Br. J. Cancer. 1997;75:829–836. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hashizume H, Baluk P, Morikawa S, McLean JW, Thurston G, Roberge S, et al. Am. J. Pathol. 2000;156:1363–1380. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65006-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mollica F, Jain RK, Netti Pa. Microvasc. Res. 2003;65:56–60. doi: 10.1016/s0026-2862(02)00012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee C, Liu K, Huang T. J. Cancer Mol. 2006;2:135–140. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kato M, Hattori Y, Kubo M, Maitani Y. Int. J. Pharm. 2012;423:428–434. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eckes J, Schmah O, Siebers JW, Groh U, Zschiedrich S, Rautenberg B, et al. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:337. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eberhard A, Kahlert S, Goede V, Hemmerlein B, Plate KH, Augustin HG. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1388–1393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Graff BA, Benjaminsen IC, Brurberg KG, Ruud E-BM, Rofstad EK. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2005;21:272–281. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boucher Y, Baxter LT, Jain RK. Cancer Res. 1990;50:4478–4484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Flessner MF, Choi J, Credit K, Deverkadra R, Henderson K. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:3117–3125. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ramanujan S, Pluen A, McKee TD, Brown EB, Boucher Y, Jain RK. Biophys. J. 2002;83:1650–1660. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73933-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Netti PA, Berk DA, Swartz MA, Grodzinsky AJ, Jain RK. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2497–2503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mirny L. Nat. Phys. 2008;4:93–95. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stylianopoulos T, Poh M-Z, Insin N, Bawendi MG, Fukumura D, Munn LL, et al. Biophys. J. 2010;99:1342–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang M, Lai SK, Wang Y-Y, Zhong W, Happe C, Zhang M, et al. Angew. Chem. 2011;50:2597–2600. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kuszyk BS, Corl FM, Franano FN, Bluemke DA, Hofmann LV, Fortman BJ, et al. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2001;177:747–753. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.4.1770747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jaeger HM, Nagel SR. Science. 1992;255:1523–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.255.5051.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Delgado J. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2006;84:651–655. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Juweid M, Neumann R, Paik C, Perez-bacete MJ, Sato J, Osdol WV, et al. Cancer Res. 1992;52:5144–5153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eikenes L, Bruland ØS, Brekken C, Davies CDL. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4768–4773. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zheng X, Goins BA, Cameron IL, Santoyo C, Bao A, Frohlich VC, et al. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2011;67:173–182. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Egeblad M, Nakasone ES, Werb Z. Dev. Cell. 2010;18:884–901. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mayer LD, Dougherty G, Harasym TO, Bally MB. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;280:1406–1414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Moore A, Weissleder R, Bogdanov A. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 1997;7:1140–1145. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880070629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chung AS, Lee J, Ferrara N. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2010;10:505–514. doi: 10.1038/nrc2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bergers G, Song S, Meyer-morse N, Bergsland E, Hanahan D. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:1287–1295. doi: 10.1172/JCI17929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Luo Y, Zhou H, Krueger J, Kaplan C, Lee S, Dolman C, et al. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:2132–2141. doi: 10.1172/JCI27648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ong S, Liu H, Pidgeon C. J. Chromatogr., A. 1996;728:113–128. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(95)00837-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Qaddoumi MG, Ueda H, Yang J, Davda J, Labhasetwar V, Lee VHL. Pharm. Res. 2004;21:641–648. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000022411.47059.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chithrani DB, Dunne M, Stewart J, Allen C, Jaffray Da. Nanomedicine. 2010;6:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gottesman MM. Cancer Res. 1993;53:747–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Eckford PDW, Sharom FJ. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:2989–3011. doi: 10.1021/cr9000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sharom FJ, Yu X, Didiodato G, Chu JWK. Biochem. J. 1996;428:421–428. doi: 10.1042/bj3200421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zamboni WC. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:8230–4. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Allen TM. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:750–763. doi: 10.1038/nrc903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Keely N, Meegan M. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2009;9:370–380. doi: 10.2174/156800909788166628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pirollo KF, Chang EH. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26:552–558. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wu AM, Yazaki PJ, Tsai S, Nguyen K, Anderson A, Mccarthy DW, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:8495–8500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150228297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kirpotin DB, Drummond DC, Shao Y, Shalaby MR, Hong K, Nielsen UB, et al. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6732–6740. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Joyce Y, Wong JY. Science. 1997;275:820–822. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5301.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang AZ, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Annu. Rev. Med. 2012;63:185–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-040210-162544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xiao Z, Levy-Nissenbaum E, Alexis F, Lupták A, Teply B, Chan JM, et al. ACS Nano. 2012;6:696–704. doi: 10.1021/nn204165v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Morton CL, Houghton PJ. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:247–250. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, et al. New Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wolff AC, Hammond MEH, Schwartz JN, Hagerty KL, Allred DC, Cote RJ, et al. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2007;131:18–43. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-18-ASOCCO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Baker J, Ajani J, Scotté F, Winther D, Martin M, Aapro MS, et al. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2009;13:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mukherjee S, Ghosh RN, Maxfield FR. Physiol. Rev. 1997;77:759–803. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Eskelinen E-L, Tanaka Y, Saftig P. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Panyam J, Zhou W-Z, Prabha S, Sahoo SK, Labhasetwar V. FASEB J. 2002;16:1217–1226. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0088com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Akinc A, Thomas M, Klibanov AM, Langer R. Gene Med. J. 2005;7:657–663. doi: 10.1002/jgm.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Calcabrini A, Meschini S, Stringaro A, Cianfriglia M, Arancia G, Molinari A. The Histochem. J. 2000;32:599–606. doi: 10.1023/a:1026732405381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kastrup L, Oberleithner H, Ludwig Y, Schafer C, Shahin V. J. Cell. Physiol. 2006;206:428–434. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Symens N, Soenen SJ, Rejman J, Braeckmans K, De Smedt SC, Remaut K. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2012;64:78–94. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Vail DM, Amantea MA, Colbern GT, Martin FJ, Hilger RA, Working PK. Semin. Oncol. 2004;31:16–35. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.O’Brien MER. Ann. Oncol. 2004;15:440–449. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gradishar WJ, Tjulandin S, Davidson N, Shaw H, Desai N, Bhar P, et al. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:7794–7803. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Janssen B, Debets J, Leenders P, Smits J. Am. J. of Physiol. 2002;282:R928–R935. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00406.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pluen A, Boucher Y, Ramanujan S, McKee TD, Gohongi T, di Tomaso E, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:4628–4633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081626898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]