Abstract

The Amaryllidaceae alkaloid bulbispermine was derivatized to produce a small group of synthetic analogues. These, together with bulbispermine’s natural crinine-type congeners, were evaluated in vitro against a panel of cancer cell lines with various levels of resistance to proapoptotic stimuli. Bulbispermine, haemanthamine and haemanthidine showed the most potent antiproliferative activities as determined by the MTT colorimetric assay. Among the synthetic bulbispermine analogues, only the C1,C2-dicarbamate derivative exhibited noteworthy growth inhibitory properties. All active compounds were found not to discriminate between the cancer cell lines based on the apoptosis sensitivity criterion and displayed comparable potencies in both cell types, indicating that apoptosis induction is not the primary mechanism responsible for antiproliferative activity in this series of compounds. It was also found that bulbispermine inhibits the proliferation of glioblastoma cells through cytostatic effects, possibly arising from the rigidification of the actin cytoskeleton. These findings lead us to argue that crinine-type alkaloids are potentially useful drug leads for the treatment of apoptosis resistant cancers and glioblastoma in particular.

Keywords: cancer, apoptosis resistance, bulbispermine, glioblastoma, alkaloid, actin cytoskeleton

Introduction

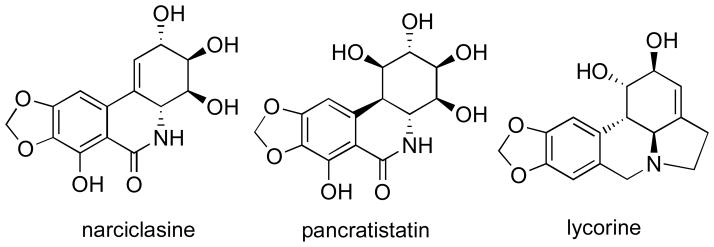

The anticancer properties of plants belonging to the Amaryllidaceae family were already known in the fourth century B.C., when Hippocrates of Cos used oil from the daffodil Narcissus poeticus L. for the treatment of uterine tumors.1 Using related biosynthetic pathways these plants produce a large number of diverse alkaloids and related non-basic metabolites, whose anticancer potential is being explored by many research groups worldwide.2 Thus, various studies have identified promising anticancer effects exhibited by isocarbostyrils narciclasine and pancratistatin, as well as the pyrrolophenanthridine alkaloid lycorine (Figure 1). These natural products have therefore been under intense scrutiny and are currently being pursued as cancer clinical candidates.3

Figure 1.

Structures of Amaryllidaceae anticancer constituents pursued as cancer clinical candidates

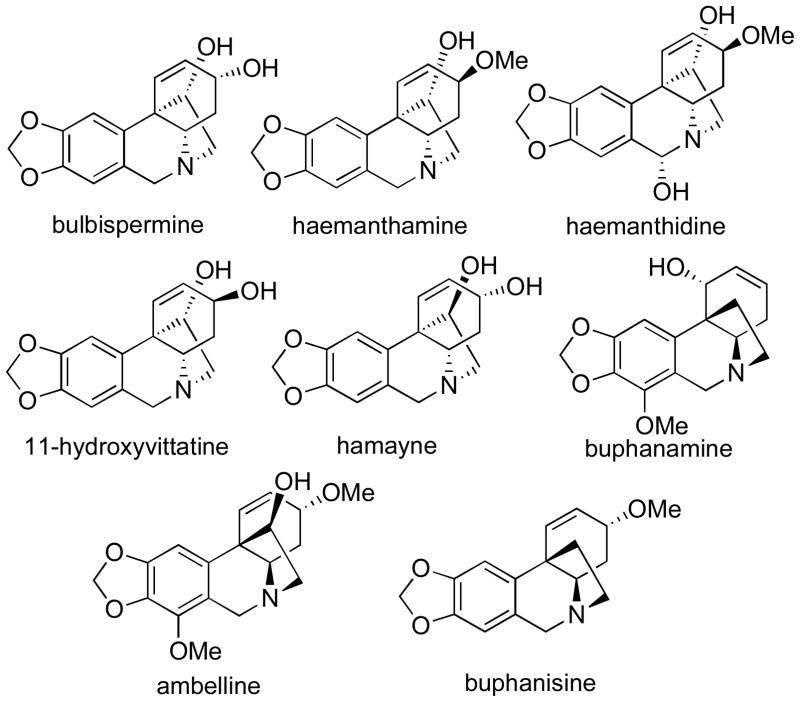

Although the ethano-bridged phenanthridine alkaloids of the crinine type (Figure 2) have also been reported to display cytotoxic4 and apoptosis-inducing5 properties, their anticancer potential remains largely unexplored and the mechanism(s) underlying their effects on cancer cells have not been investigated.

Figure 2.

Structures of selected crinine type alkaloids

Recently, we reported biochemical experiments providing a mechanistic insight into the antiproliferative effects induced by narciclasine and lycorine.3a,b,d We showed that at therapeutic concentrations, both narciclasine and lycorine do not induce apoptosis in cancer cells, but rather exhibit cytostatic effects through the targeting of the actin cytoskeleton. This mode of action thus accounts for their promising activities against cancer cells, which are resistant to proapoptotic stimuli and therefore representative of tumors associated with dismal prognoses, such as melanoma, glioblastoma, and non-small-cell lung cancer. Herein, we show that the crinine-type alkaloids exhibit useful cytostatic properties as well, and that these effects are most likely caused by the targeting of the actin cytoskeleton organization in cancer cells. These findings warrant further investigation of the crinine-type alkaloids as promising potential agents for the treatment of apoptosis-resistant cancers, such as glioblastoma.6

Results and discussion

Isolation and structure confirmation

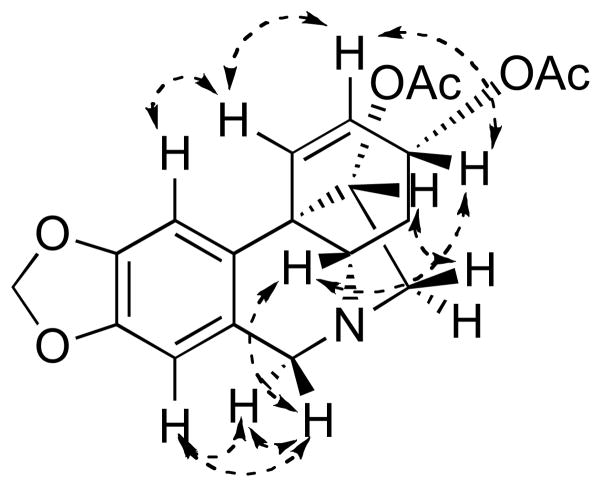

The alkaloid bulbispermine (Figure 2), previously isolated from different Amaryllidaceae plants,7 has been reported to have cytotoxic activity against HL-60 cells.7c We serendipitously isolated a significant quantity of this alkaloid from Zephyranthes robustus while investigating this plant as a potential source of pancratistatin.8 Although this plant had not been previously reported as a source of bulbispermine, it appeared to contain significant quantities of this alkaloid (70 mg per kg of fresh bulbs). However, because of the problems with plant availability, we subsequently switched to the known source of bulbispermine, Crinum bulbispermum (160 mg per kg of fresh bulbs).7b Although the NMR spectra of the isolated bulbispermine were consistent with those in the literature,9 we were concerned with their similarity to the NMR spectroscopic data of the stereoisomeric alkaloids, 11-hydroxyvittatine and hamayne (Figure 2). Therefore, we obtained unambiguous proof of stereochemistry by converting a portion of bulbispermine to its diacetate (1) and analyzing the structure with NOESY (Figure 3). Finally, in terms of natural product isolation, additional crinine-type alkaloids, namely haemanthamine, haemanthidine, buphanamine, buphanisine and ambelline (Figure 2), were obtained using the procedures previously utilized in our laboratory as detailed in the Experimental Section.

Figure 3.

NOE correlations in 1 confirming the stereochemical relationships

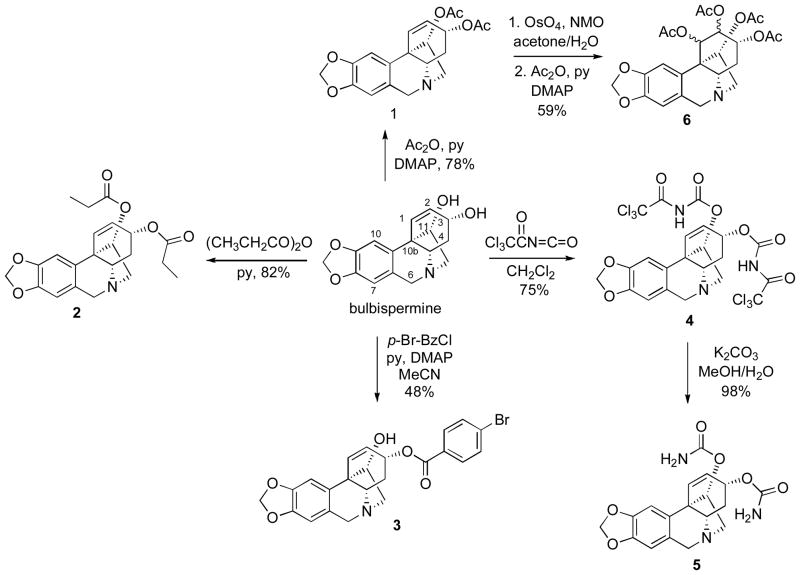

Synthetic Chemistry

After sufficient quantities of bulbispermine were isolated, we performed its chemical derivatization and subsequently obtained a small group of analogues. Thus, the hydroxyl groups in bulbispermine were acetylated and propionylated to give esters 1 and 2 (Scheme 1). The reaction with one equivalent of p-bromobenzoyl choride resulted in selective esterification of the more sterically accessible allylic hydroxyl at C3. It should also be noted that the other hydroxyl at C11 is located vicinal to the C10b quaternary carbon center, thus facilitating this outcome. As these derivatizations lead to the introduction of hydrophobic groups on the two hydroxyls, we next sought to derivatize them as polar carbamates. We achieved this goal by first reacting bulbispermine with trichloroacetyl isocyanate to give intermediate 4, which was then converted into dicarbamate 5 through basic hydrolysis. Our attempts to selectively dihydroxylate the double bond in diacetate 1 were unsuccessful and we obtained tetraacetate 6 as a mixture of diastereomers at C1 and C2 (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Derivatization of the hydroxyl groups

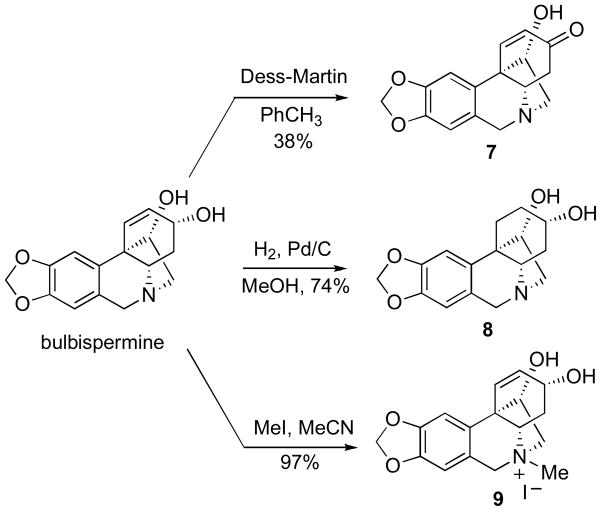

Additional bulbispermine derivatization (Scheme 2) involved selective oxidation of the allylic alcohol to give C3-ketone 7, hydrogenation of the double bond to provide C1,C2-saturated analogue 8 and lastly quaternization of the nitrogen atom to result in ammonium iodide salt 9.

Scheme 2.

Additional bulbispermine derivatization

Biochemical Experiments

The synthesized compounds were next evaluated for in vitro growth inhibition using the MTT colorimetric assay3a,l against a panel of five cancer cell lines including two resistant to proapoptotic stimuli, such as human U373 and T98G glioblastoma (GBM, from astroglial origin10a,b),3a,10b as well as apoptosis-sensitive tumor models, such as human Hs683 anaplastic oligodendroglioma3a,10b and HeLa cervical adenocarcinoma. An additional U87 human glioblastoma cell line, whose apoptosis resistance properties have not been investigated,10c was also included. Analysis of the antiproliferative data reveals that active compounds (bulbispermine, haemanthamine, haemanthidine and synthetic derivatives 1 and 5) do not discriminate between the cancer cell lines based on the apoptosis sensitivity criterion and display comparable potencies in both cell types, indicating that apoptosis induction is not the primary mechanism responsible for antiproliferative activity in this series of compounds, at least in solid cancers (see Table). Furthermore, three of the natural alkaloids containing the α-C11,C12-ethano bridge (bulbispermine, haemanthamine and haemanthidine) are all active, in contrast to their counterparts incorporating this C11–C12 subunit in the β-position (buphanamine, buphanisine and ambelline). These observations are consistant with the previous literature findings4i,11 and they point to the criticality of this structural feature for antiproliferative activity in the crinine-type alkaloids. Of the synthetic bulbispermine derivatives, the only noteworthy activity is found for compound 5, in which the C3,C11-hydroxyls are converted into polar carbamates, demonstrating that derivatization of the hydroxyls with hydrophobic groups leads to an apparent loss of activity. Of interest is also the importance of the C1,C2-olefinic functionality, because analogue 8, in which the double bond is hydrogenated, is inactive. Finally, it is noteworthy that the lack of anticancer activity of analogues 7–9 is consistent with the previous literature describing that similar modifications of the lycorine skeleton resulted in inactive compounds.3d,11

Table.

Evaluation of the natural and synthetic crinine-type compounds against cancer cells resistant or sensitive to proapoptotic stimuli.

| compounds | GI50

in vitro values (μM)a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| apoptosis-resistant cell lines | apoptosis-sensitive cell lines | unknown apoptosis-sensitivity cell line | |||

|

| |||||

| T98G | U373 | Hs683 | HeLa | U87 | |

|

| |||||

| bulbispermine | 9 | 38 | 11 | 8 | 9 |

| haemanthamine | 8 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| haemanthidine | 14 | 7 | 4 | NDb | 6 |

| buphanamine | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| buphanisine | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| ambelline | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 1 | 98 | ND | 63 | 90 | 74 |

| 2 | >100 | ND | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 3 | >100 | ND | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 4 | >100 | ND | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 5 | 91 | >100 | 50 | 46 | 15 |

| 6 | >100 | ND | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 7 | >100 | ND | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 8 | >100 | ND | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 9 | >100 | ND | >100 | >100 | >100 |

Table values represent the average of IC50 values generated from two independent experiments.

ND: “not determined”

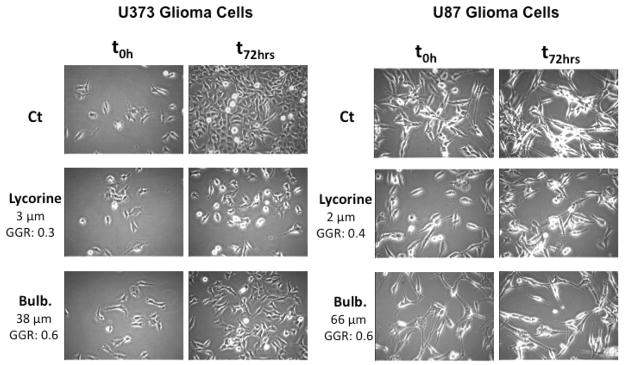

We also made use of computer-assisted phase-contrast microscopy (quantitative videomicroscopy) to analyze the principal mechanism of action associated with bulbispermine’s in vitro growth inhibitory effects, as first revealed by the MTT colorimetric assay. Figure 4 shows that bulbispermine inhibits cancer cell proliferation without inducing cell death when assayed at its IC50 in vitro growth inhibitory value in U373 GBM cells or even at the concentration of seven times its IC50 antiproliferative value in U87 GBM cells. Based on the phase contrast pictures obtained by means of quantitative videomicroscopy, we calculated the global growth rate (GGR), which corresponds to the ratio of the mean number of cells present in the last image captured in the experiment (conducted at 72 h) to the number of cells present in the first image (at 0 h). We divided this ratio obtained in the bulbispermine-treated experiment by the ratio obtained in the control. Lycorine, which we established to be a cytostatic compound in these cell lines previously,3d was used as a positive control. A GGR value of 0.6 in both cell lines means that 60% of cells grew in the bulbispermine-treated experiment as compared to the control over a 72-h observation period.

Figure 4.

Cellular imaging of bulbispermine (Bulb.) against U373 and U87 glioma cells illustrating non-cytotoxic, but cytostatic, antiproliferative mechanism at MTT colorimetric assay-related IC50 (U373) as well as 7×IC50 (U87) concentrations.

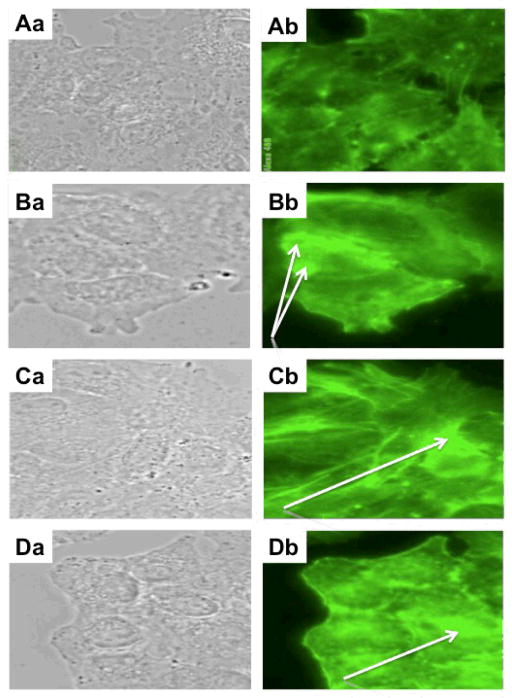

Our previous work with narciclasine3a and lycorine3d revealed that their cytostatic effects on cancer cells mainly occur during cytokinesis, through the increase in rigidity of the actin cytoskeleton. Our experiments with bulbispermine and its active analogue 5 also revealed that at their in vitro growth inhibitory IC50 concentrations these compounds markedly increased the levels of polymerized actin in Hs683 glioma cells (green fluorescence in Figures 5Cb and 5Db) when compared to the control (Figure 5Ab). These effects of the increased rigidity of the actin cytoskeleton induced by bulbispermine and its synthetic analogue 5 thus closely resemble those of narciclasine (Figure 5Bb).

Figure 5.

Effects on actin cytoskeleton organization by bulbispermine and analogue 5 at their in vitro growth inhibitory IC50 concentrations in Hs683 glioma cells. A: control (untreated) conditions (Aa: bright field; Ab: actin cytoskeleton). B: 100 nM positive control narciclasine-treated (Ba: bright field; Bb: actin cytoskeleton) conditions. C: 10 μM bulbispermine-treated (Ca: bright field; Cb: actin cytoskeleton) conditions. D: 50 μM analogue 5-treated (Da: bright field; Db: actin cytoskeleton) conditions. Narciclasine (Bb), bulbispermine (Cb) and analogue 5 (Db) rigidify the actin cytoskeleton by increasing the amounts of polymerized actin as evidenced by the white arrows.

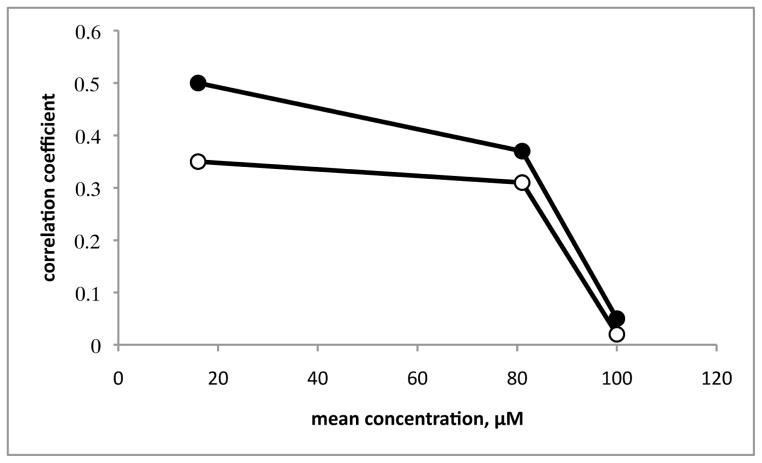

Correlations of the differential cellular sensitivities in the US National Cancer Institute 60-cell line screen confirmed this proposed mode of action for crinine-type alkaloids. While bulbispermine has not been tested at NCI, the data are available for its congener haemanthamine (Figure 2). Thus, the “Compare Correlation Coefficients” indicate that at its mean GI50 value (16 μM) characteristic of growth inhibition (Figure 6) the differential cellular sensitivities for haemanthamine are similar to those of known actin cytoskeleton modulators rapamycin12 and isocarbostyril pancratistatin3b (the correlation coefficients are 0.5 and 0.35, respectively). However, the uniformity of the mechanism among these compounds disappears if the correlations are performed at their mean LC50 values, characteristic of cell death (no correlation obtained for 100 μM haemanthamine). Therefore, when used at cytotoxic doses, haemanthamine probably interacts with other lower affinity targets, which are not necessarily the same for rapamycin and pancratistatin.

Figure 6.

Correlations of the differential cellular sensitivities in the NCI 60-cell line screen using the COMPARE algorithm. “Compare Correlation Coefficients” were generated by a computerized pattern recognition algorithm and serve as an indication of similarities in differential cellular sensitivities or characteristic fingerprints for each compound. Haemanthamine was used as a seed to find significant correlations with the anticancer agents in the NCI Standard Compound Database, containing rapamycin and pancratistatin at the GI50, TGI and LC50 levels (for definitions of these parameters, see DTP Human Tumor Cell Line Screen http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/branches/btb/ivclsp.html). At the GI50 level (16 μM), the correlations identified rapamycin (filled circles) and pancratistatin (open circles) as highly ranked agents among the compounds in the database with Compare Correlation Coefficients of 0.5 and 0.35 respectively. While the correlations at the TGI level (80 μM) were worse but still significant (Compare Correlation Coefficients of 0.37 and 0.34), the LC50 levels (100 μM) were not correlated at all.

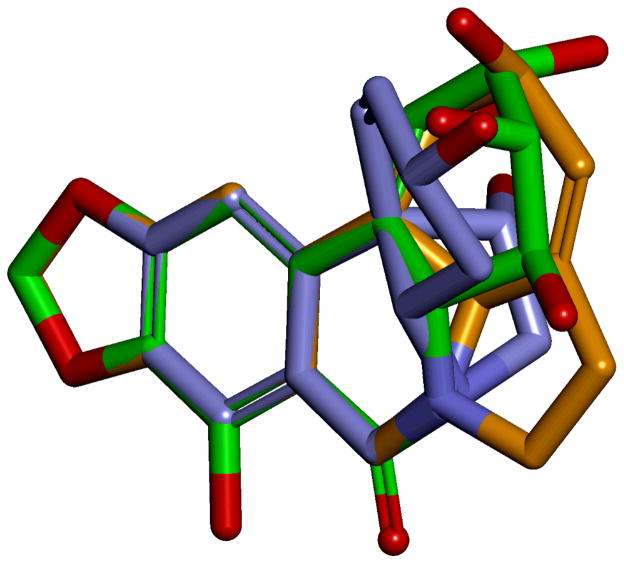

Computer Modeling

The similarity of the effects on cancer cells exhibited by the previously investigated narciclasine and lycorine, as well as the currently described crinine-type alkaloids, gives rise to an important question of whether the structural skeletons associated with these three types of Amaryllidaceae constituents share the same chemical space and are capable of targeting the same intracellular macromolecules. For the purposes of investigating the structural relationship between narciclasine, lycorine and bulbispermine (Figure 7) we undertook a conformational search to find the lowest energy conformation for each structure and these were superimposed. It is clear that the three structures have in common the hydrogen bond acceptor methylenedioxy moiety, the aromatic region and the positioning of the nitrogen. Interestingly, in all three compounds this nitrogen would serve as a potential hydrogen bond donor group, as in narciclasine it is found as the amide –NH, and in lycorine and bulbispermine it will be in the protonated form at physiological pH. Therefore it is highly probable that these three regions represent the common pharmacophore for the three structures in their mode of action. Diversification in the structures is tolerated in the hydroxyl-containing portions of the three compounds indicative that this region is possibly pointing away from the putative binding site(s).

Figure 7.

Superimposition of narciclasine (green), lycorine (orange) and bulbispermine (purple) showing high similarity in the methylenedioxy, aromatic and nitrogen portions of the structures.

Conclusion

Malignant gliomas, which include anaplastic astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, oligoastrocytoma and glioblastoma, account for more than 50% of all primary brain tumors.6 Of these, glioblastoma multiforme represents the highest grade of malignancy and is associated with dismal prognoses. Glioblastoma cells display resistance to apoptosis, which contributes to their poor response to conventional chemotherapy with proapoptotic agents.6 In our previous work we identified Amaryllidaceae small molecule constituents narciclasine and lycorine as promising anticancer agents exhibiting useful antiproliferative effects toward glioblastoma cells resistant to proapoptotic stimuli. In this paper we demonstrate that another group of Amaryllidaceae constituents, namely crinine-type alkaloids, are also potentially useful drug leads for the treatment of apoptosis-resistant cancers and glioblastoma in particular. We show that a representative crinine-type alkaloid bulbispermine inhibits the proliferation of glioblastoma cells through cytostatic effects possibly arising from the rigidification of the actin cytoskeleton. Computer-assisted superimposition of the lowest energy conformations of narciclasine, lycorine and bulbispermine indicates that these three molecules, representative of three major Amaryllidaceae anticancer scaffolds, occupy similar regions in chemical space and they indeed could be targeting the same intracellular macromolecules to induce cytostatic effects in cancer cells.

Experimental Section

General

All commercially obtained reagents were used without purification unless otherwise noted. THF and toluene were distilled from sodium benzophenone-ketyl prior to use. CH2Cl2 was distilled from CaH2 and kept under Argon. Reactions were monitored by TLC (EM Science, Silica Gel 60 F254, 250 μm) and visualized with UV light or I2. When appropriate, reactions were run under N2 or argon in oven dried glassware using standard syringe, cannula, and septa techniques. Flash chromatography was performed on silica gel (Silica gel, 32–63 μm, 60 Å pore size). 1H- and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on JEOL 300 MHz and Bruker 400 MHz spectrometers. HRMS was performed at the University of New Mexico mass spectrometry facility.

Alkaloids

Bulbispermine was isolated from dried bulbs of Crinum Bulbispermum as previously reported.7b Haemanthamine was isolated from Egyptian Pancratium maritinum.13 Ambelline, buphanamine and buphanisine were generously supplied by Prof. Fales, H. M. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Bethesda, MD, USA. Haemanthidine was purified from dried bulbs of Lycoris aurea.14 The purity of the samples was confirmed by TLC, mp, optical rotation, 1H and 13C NMR, NOESY, and ESI-MS analyses.

Bulbispermine

1H NMR (CD3OD, 300 MHz) δ 6.85 (s, 1H, H-10), 6.52 (s, 1H, H-7), 6.23 (dd, 1H, J = 9.1 Hz, 2.2 Hz, H-2), 6.04 (d, 1H, 9.1 Hz, H-1), 5.87 (s, 2H, -OCH2O-), 4.36-4.29 (m, 1H, H-3), 4.27 (d, 1H, J = 16.7 Hz, H-6β), 3.95 (dd, 1H, J = 8.3 Hz, 6.0 Hz, H-11), 3.73 (d, 1H, J = 16.7 Hz, H-6α), 3.44 (1H, dd, J = 13.6 Hz, 7.1 Hz, H-4a), 3.25-3.17 (m, 2H, H-12), 2.15-2.03 (m, 1H, H-4), 1.98-1.91 (m, 1H, H-4); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ 148.5 (C-9), 148.0 (C-8), 137.4 (C-10a), 136.7 (C-1), 125.2 (C-6a), 124.2 (C-2), 107.9 (C-10), 104.4 (C-7), 102.4 (-OCH2O-), 80.4 (C-11), 68.0 (C-3), 67.7 (C-4a), 63.3 (C-12), 60.9 (C-6), 51.6 (C-10b), 33.8 (C-4).

Compound 1

To a solution of bulbispermine (10.0 mg, 0.0348 mmol) in pyridine (3.0 mL) was added acetic anhydride (2.0 mL) and a catalytic amount of DMAP (0.1 mg, 0.9 μmol). The reaction was stirred at r.t. overnight, and the following day was co-evaporated several times with toluene to remove pyridine. The resulting residue was purified by PTLC using 98: 2 CH2Cl2: MeOH yielding 5.1 mg of the diacetate (78 %). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 6.86 (s, 1H, H-10), 6.47 (s, 1H, H-7), 6.22 (dd, 1H, J = 10.4 Hz, 2.2 Hz, H-1), 5.91 (s, 2H, -OCH2O-), 5.86 (d, 1H, J = 10.4 Hz, H-2), 5.48-5.42 (m, H-3β), 4.99-4.31 (m, 1H, H-11exo), 3.34 (d, 1H, J = 17.0 Hz, H-6β), 3.71 (d, 1H, J = 17.0 Hz, H-6α), 3.40 (d, 2H, J = 5.2 Hz, H-12), 3.28 (dd, 1H, J = 13.5 Hz, H-4a), 2.12-2.17 (m, 2H, H-4), 2.09 (s, -OAc), 2.04 (s, OAc); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 170.6 (C=O), 170.3 (C=O), 146.9 (C-9), 146.8 (C-8), 134.0 (C-10a), 131.4 (C-1), 126.3 (C-6a), 125.6 (C-2), 106.8 (C-10), 103.9 (C-7), 101.1 (-OCH2O-), 80.4 (C-11), 70.0 (C-3), 66.2 (C-4a), 61.1 (C-6), 49.4 (C-10b), 29.8 (C-4), 21.4 (CH3), 21.3 (CH3). HRMS m/z (ESI+) calc’d for C20H22NO6 (M + H+) 372.1447, found 372.1449.

Compound 2

To a solution of bulbispermine (5.0 mg, 0.0174 mmol) in pyridine (1.5 mL) was added propionic anhydride (1.0 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. overnight, and the following day was co-evaporated with toluene several times to remove pyridine. The resulting residue was purified by PTLC using 98: 2 CH2Cl2: MeOH yielding 5.6 mg of the dipropionate (82%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 6.89 (s, 1H, H-10), 5.50 (s, 1H, H-7), 6.23 (d, 1H, J = 10.4 Hz, H-1), 5.93 (s, 2H, -OCH2O-), 5.87 (d, 1H, J = 10.4 Hz, H-2), 5.51-5.47 (m, 1H, H-3), 5.03-5.00 (m, 1H, H-11), 4.39 (d, 1H, J = 17.2 Hz, H-6β), 3.77 (d, 1H, J = 17.2 Hz, H-6α), 3.46-3.44 (m, 2H, H-12), 3.33 (dd, 1H, J = 13.7 Hz, 3.04 Hz, H-4a), 2.40-2.31 (m, 4H, -CH2CO-), 2.23-2.19 (m, 1H), 1.19-1.14 (m, 6H, -CH3); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 174.0 (C=O), 173.6 (C=O), 147.0 (C-9), 146.8 (C-8), 131.5 (C-10a), 125.3 (C-2), 106.8 (C-10), 104.0 (C-7), 101.1 (-OCH2O-), 79.8 (C-11), 69.6 (C-3), 66.1 (C-4a), 60.9 (C-12), 60.2 (C-6), 49.4 (C-10b), 29.6 (C-4), 28.0, 27.9, 9.2, 9.1. HRMS m/z (ESI+) calc’d for C22H25NO6 (M + H+) 400.1760, found 400.1761.

Compound 3

A solution of p-bromobenzoyl chloride in MeCN (0.5 mL, 0.0163 mmol) was added drop-wise to a solution of bulbispermine (10.0 mg, 0.0384 mmol) in pyridine (0.5 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. overnight, and the resulting solution was diluted with a 5 % (wt/v) solution of NaHCO3 (1 mL). The aqueous solution was extracted from with EtOAc (3 × 1 mL), and the organic layers were combined and dried with MgSO4. After removal of the solvent, the residue was purified using PTLC and with the eluent system 95: 5 CH2Cl2: MeOH to furnish 8.6 mg of mono p-bromobenzoate (48%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 8.94 (d, 2H, J = 5.1 Hz, PhH), 8.59 (d, 2H, J = 5.1 Hz, PhH), 6.82 (s, 1H, H-10), 6.51 (s, 1H, H-7), 6.39 (d, 1H, J = 12.0 Hz, H-1), 6.24 (d, 1H, J = 12.0 Hz, H-2), 5.94 (s, 2H, - OCH2O-), 5.75-5.66 (m, 1H, H-3), 4.36 (d, 1H, J = 18.0 Hz, H-6β), 4.09-4.05 (m, 1H, H-11), 3.71 (d, 1H, J = 18.0 Hz, H-6α), 3.49-3.34 (m, 2H, H-12), 2.46-2.32 (m, 2H, H-4), 2.25-2.16 (m, H-4); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 165.6, 146.7, 146.5, 134.1, 131.8, 131.4, 126.7, 125.4, 107.1, 103.3, 101.1, 80.3, 71.3, 66.1, 63.6, 61.4, 50.3, 31.1, 30.0. HRMS m/z (ESI+) calc’d for C23H20BrNO5 (M + H+) 472.0583, found 472.0568.

Compound 4

To a solution of bulbispermine (5.0 mg, 0.0174 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (0.174 mL) cooled to 0 °C was added trichloroacetyl isocyanate (4.1 μL, 0.0348 mmol). The reaction was stirred at 0 °C for 20 min, and the CH2Cl2 was evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude material was purified by PTLC using 10 % MeOH in DCM resulting in 8.4 mg imidocarbamate (75%). 1H NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ 7.03 (s, 1H, H-10), 6.67 (s, 1H, H-7), 6.46 (d, 1H, J = 10.4 Hz, H-1), 6.15 (d, 2H, J = 10.4 Hz, H-2), 5.97 (s, -OCH2O-), 5.54-5.52 (m, 1H, H-3), 5.13-5.11 (m, 1H, H-11), 4.56 (d, 1H, J = 15.9 Hz, H-6β), 4.05 (d, 1H, J = 15.9 Hz, H-6α), 3.83-3.67 (m, 3H), 2.42-2.34 (m, 2H, H-4). HRMS m/z (ESI+) calc’d for C18H20N3O6 (hydrolysis product M + H+) 374.1352, found 374.1346.

Compound 5

To a solution of bulbispermine (5.0 mg, 0.0174 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (0.174 mL) cooled to 0 °C was added trichloroacetyl isocyanate (4.1 μL, 0.0348 mmol). After being stirred at 0 °C for 20 min, CH2Cl2was evaporated. The resulting residue was dissolved in methanol (0.1 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. Water (0.5 mL) and potassium carbonate (0.19 g, 1.38 mmol) was added, and the cooling bath was removed. After stirring at room temperature for 3 h, methanol was evaporated, and the resulting aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic extracts were dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated to afford 4.7 mg of the dicarbamate (74 %). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 6.95 (s, 1H, H-10), 6.59 (s, 1H, H-7), 6.35 (d, 1H, J = 10.8 Hz, H-1), 5.97 (d, 1H, J = 10.8 Hz, H-2), 5.96 (s, 2H, -OCH2O-), 5.32-5.28 (m, 1H, H-3), 4.39 (d, 1H, J = 16.5 Hz, H-6β), 3.85 (d, 1H, J = 16.5, H-6α), 3.67 (s, 2H, H-12), 3.56 (dd,1H, J = 14.2 Hz, 7.7 Hz, H-4a), 3.45-3.40 (m, 1H, H-11), 2.15-2.07 (m, 2H, H-4). HRMS m/z (ESI+) calc’d for C18H20N3O6 (M + H+) 374.1352, found 374.1352.

Compound 6

Diacetate 1 (5.0 mg, 0.0174 mmol) was dissolved in acetone (6 mL) and solution of OsO4 (0.25 mL, 2.5 % wt solution in t-BuOH), 0.038 g of NMO (0.284 mmol) in water (1.5 mL) were added over 5 min. The solution was stirred at room temperature for 6 hrs after which the solvents were evaporated under reduced pressure. To the obtained slurry were added EtOAc (2 mL) and saturated NH4Cl (1 mL), followed by washing with saturated NaCl (1 mL). The extraction was repeated twice with EtOAc (2 mL) and the combined organic layers were dried with MgSO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and subjected to PTLC using 4: 1 CH2Cl2: MeOH yielding an inseparable mixture of diastereomers. The mixture was subjected to standard acetylation conditions (2.2 eq (Ac)2O, pyridine, DMAP) in an attempt to resolve the mixture which yielded 4.9 mg (59%) of another inseparable mixture of the diastereomeric tetraacetates 6 that were biologically evaluated as a mixture. HRMS m/z (ESI+) calc’d for C24H28NO10 (M + H+) 490.1713, found 490.1704.

Compound 7

An oven-dry flask was charged with bulbispermine (10.0 mg, 0.0348 mmol) and Dess-Martin periodinane (0.044 g, 0.103 mmol) and was subjected to several cycles of vacuum-argon purge. Dry toluene (2 mL) was added, and the reaction suspension was heated for 2 hours until the substrate was completely consumed. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure, and the resulting residue was purified by PTLC using CH2Cl2: MeOH (9: 1) yielding 3.7 mg of the allylic ketone (38 %). 1H NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ 7.69 (d, 1H, J = 10.2 Hz, H-2), 7.11 (s, 1H, H-10), 6.69 (s, 1H, H-7), 6.24 (d, 1H, J = 10.2 Hz, H-1), 5.97 (d, 2H, J = 5.4 Hz, -OCH2O-), 4.58 (d, 1H, J = 17.1 Hz, H-6β), 3.98 (d, 1H, J = 17.1 Hz, H-6α), 3.91 (dd, 1H, J = 13.2 Hz, 6.3 Hz, H-4a), 3.80 (d, 1H, J = 18.6 Hz), 3.51 (d, 1H, J = 18.6 Hz), 3.25 (d, 1H, J = 11.6 Hz), 2.76-2.61 (m, 2H, H-4). 13C NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ 206.5 (C-3), 197.0 (C-9), 148.1 (C-8), 143.7 (C-10a), 130.7 (C-1), 126.9 (C-6a), 125.7 (C-2), 107.0 (C-10), 103.3 (-OCH2O-), 101.5 (C-11), 66.0 (C-4a), 58.9 (C-12), 58.3 (C-6), 48.5 (C-10b), 39.4 (C-4). HRMS m/z (ESI+) calc’d for C16H16NO4 (M + H+) 286.1079, found 286.1046.

Compound 8

A solution of bulbispermine (10.0 mg, 0.0348 mmol) in MeOH (4.2 mL) was charged with Pd/C 5 % (11.5 mg) and purged with an H2 balloon. The stirred reaction mixture was kept under an H2 atmosphere overnight at r.t. after which the solution was filtered through celite and the solvent evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting white solid was purified by PTLC using 9: 1 CH2Cl2: MeOH to yield 7.4 mg of reduced product (74 %). 1H NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ 6.76 (s, 1H, H-10), 6.51 (s, 1H, H-7), 5.89 (s, 2H, -OCH2O-), 4.30 (d, 1H, J = 16.7 Hz, H-6β), 4.04-4.03 (m, 1H, H-3), 3.75 (d, 1H, J = 16.7 Hz, H-6α), 3.67-3.61 (m, 1H, H-11), 3.40-3.39 (m, 1H, H-4a), 3.24 (dd, 1H, J = 11.3 Hz, 5.1 Hz, H-2), 3.09 (dd, 1H, J = 12.8 Hz, 4.84 Hz, H-2), 2.68 (dd, 1H, J = 14.0 Hz, 4.0 Hz, H-1), 2.12-2.03 (m, 2H, H-4), 1.99-1.78 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ 146.9 (C-8), 146.2 (C-9), 138.7 (C-10a), 124.6 (C-6a), 105.7 (C-7), 103.2 (C-10), 100.8 (-OCH2O-), 81.2 (C-11), 68.6 (C-3), 66.9 (C-4a), 62.0 (C-12), 59.8 (C-6), 45.8 (C-10b), 35.4 (C-4), 32.1 (C-2), 25.6 (C-1). HRMS m/z (ESI+) calc’d for C16H20NO4 (M + H+) 290.1392, found 290.1399.

Compound 9

To a solution of bulbispermine (5.0 mg, 0.0174 mmol) in dry MeCN (0.3 mL) was added 1.1 eq of MeI. After 5 min, the reaction turned milky, and was reacted until starting material had been totally consumed after 2 hr. The resulting precipitate was filtered, and washed with cold MeCN, followed by CHCl3 resulting in 7.3 mg of a white solid ammonium salt (97 %). 1H NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ 7.02 (s, 1H, H-10), 6.71 (s, H-7), 6.23-6.17 (m, 2H, H-1 & H-2), 6.01 (s, 2H, -OCH2O-), 4.69 (d, 1H, J = 15.8 Hz, H-6α), 4.62 (s, 1H), 4.44-4.39 (m, 1H, H-3), 3.79-3.75 (m, 2H), 3.35 (s, 3H, N-CH3), 2.50-2.40 (m, 2H, H-4). HRMS m/z (ESI+) calc’d for C17H20NO4 (M+) 302.1392, found 302.1385.

Biochemical Experiments

The overall growth level of human cancer cell lines was determined using the colorimetric MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl]-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide, Sigma, Belgium) assay.3a,3d Briefly, the cell lines were incubated for 24 h in 96-microwell plates (at a concentration of 10,000 to 40,000 cells/mL culture medium depending on the cell type) to ensure adequate plating prior to cell growth determination. The assessment of cell population growth by means of the MTT colorimetric assay is based on the capability of living cells to reduce the yellow product MTT (3-(4,5)-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) to a blue product, formazan, by a reduction reaction occurring in the mitochondria. The number of living cells after 72 h of culture in the presence (or absence: control) of the various compounds is directly proportional to the intensity of the blue, which is quantitatively measured by spectrophotometry – in our case using a Biorad Model 680XR (Biorad, Nazareth, Belgium) at a 570 nm wavelength (with a reference of 630 nm). One set of experimental conditions included six replicates. Each experiment was carried out twice.

Cell proliferation was visualized by means of computer-assisted phase contrast microscopy.3a,3d,15 The fibrillar actin cytoskeleton organization was determined by means of computer-assisted fluorescence microscopy.3a,3d Phallacidin conjugated with the green-fluorescent Alexa Fluor488 (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, Oregon) was used to label the fibrillar actin.

Computer modelling

Conformations of narciclasine, lycorine and bulbispermine were generated using Accelrys Discovery Studio 3.1. All conformers were minimized and structures with a RMSD > 0.2 were retained. For the purposes of the overlay, the lowest energy conformation was selected for each structure and superimposition utilizing tethers was employed to bring into alignment the dioxolane and aromatic regions of the structures.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the US National Institutes of Health (RR-16480 and CA-135579) under the BRIN/INBRE and AREA programs. R. K. is a director of research with the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (FNRS, Belgium). In addition, grants from the Italian Ministry of University and Research are gratefully acknowledged. This work was also supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF), Pretoria, and Stellenbosch University (Faculty and Departmental funding), Stellenbosch, South Africa. R. J. and S. R. wish to thank Dr. Michaelann Tartis for her advice.

References

- 1.a) Gardeil JB, translator. Traduction des Oeuvres Médicales d’Hippocrate, Fages, Meilhec et Cie: Toulouse. 1801. 4 vols. [Google Scholar]; b) Jin Z. Nat Prod Rep. 2011;28:1126. doi: 10.1039/c0np00073f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornienko A, Evidente A. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1982. doi: 10.1021/cr078198u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Ingrassia L, Lefranc F, Dewelle J, Pottier L, Mathieu V, Spiegl-Kreinecker S, Sauvage S, ElYazidi M, Dehoux M, Berger W, VanQuaquebeke E, Kiss R. J Med Chem. 2009;52:1100. doi: 10.1021/jm8013585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Van Goietsenoven G, Hutton J, Becker JP, Lallemand B, Robert F, Lefranc F, Pirker C, Vandenbussche G, Van Antwerpen P, Evidente A, Berger W, Prévost M, Pelletier J, Kiss R, Kinzy TG, Kornienko A, Mathieu V. FASEB J. 2010;24:4575. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-162263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lefranc F, Sauvage S, Van Goietsenoven G, Mégalizzi V, Lamoral-Theys D, Debeir O, Spiegl-Kreinecker S, Berger W, Mathieu V, Decaestecker C, Kiss R. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1739. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Lamoral-Theys D, Andolfi A, Van Goietsenoven G, Cimmino A, Le CalveéN B, Wauthoz, Megalizzi V, Gras T, Bruyere C, Dubois J, Mathieu V, Kornienko A, Kiss R, Evidente A. J Med Chem. 2009;52:6244. doi: 10.1021/jm901031h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Evdokimov N, Lamoral-Theys D, Mathieu V, Andolfi A, Pelly SC, van Otterlo WAL, Magedov IV, Kiss R, Evidente A, Kornienko A. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:7252. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.09.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Pettit GR, Orr B, Ducki S. Anti-Cancer Drug Des. 2000;15:389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Pettit GR, Melody N, Simpson M, Thompson M, Herald DL, Knight JC. J Nat Prod. 2003;66:92. doi: 10.1021/np020225i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) McNulty J, Thorat A, Vurgun N, Nair JJ, Makaji E, Crankshaw DJ, Holloway AC, Pandey S. J Nat Prod. 2011;74:106. doi: 10.1021/np100657w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) McLachlan A, Kekre N, McNulty J, Pandey S. Apoptosis. 2005;10:619. doi: 10.1007/s10495-005-1896-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Vshyvenko S, Scattolon J, Hudlicky T, Romero AE, Kornienko A. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:4750. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Collins J, Rinner U, Moser M, Hudlicky T, Ghiviriga I, Romero AE, Kornienko A, Ma D, Griffin C, Pandey S. J Org Chem. 2010;75:3069. doi: 10.1021/jo1003136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Mosmann T. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Kim YH, Park EY, Park MH, Badarch U, Woldemichael GM, Beutler JA. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:2140. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Evidente A, Kireev AS, Jenkins AR, Romero AE, Steelant WFA, Van slambrouck S, Kornienko A. Planta Med. 2009;75:501. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lin LZ, Hu SF, Chai HB, Pengsuparp T, Pezzuto JM, Cordell GA, Ruangrungsi N. Phytochemistry. 1995;40:1295. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00372-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Hohmann J, Forgo P, Molnar J, Wolfard K, Molnar A, Thalhammer T, Mathe I, Sharples D. Planta Med. 2001;68:454. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Furusawa E, Irie H, Combs D, Wildman WC. Chemotherapy. 1980;26:36. doi: 10.1159/000237881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Weniger B, Italiano L, Beck JP, Bastida J, Bergonon S, Codina C, Lobstein A, Anton R. Planta Med. 1995;61:77. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-958007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Abd Eil Hafiz MA, Ramadan MA, Jung ML, Beck JP, Anton R. Planta Med. 1991;57:437. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Likhitwitayawuid K, Angerhofer CK, Chai H, Pezzuto JM, Cordell GA. J Nat Prod. 1993;56:1331. doi: 10.1021/np50098a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Van Goietsenoven G, Andolfi A, Lallemand B, Cimmino A, Lamoral-Theys D, Gras T, Abou-Donia A, Dubois J, Lefranc F, Mathieu V, Kornienko A, Kiss R, Evidente A. J Nat Prod. 2010;73:1223. doi: 10.1021/np9008255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Silva AFS, de Andrade JP, Machado KRB, Rocha AB, Apel MA, Sobral MEG, Henriques AT, Zuanazzi JAS. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:882. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Griffin C, Sharda N, Sood D, Nair J, McNulty J, Pandey S. Cancer Cell Int. 2007;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) McNulty J, Nair JJ, Codina C, Bastida J, Pandey S, Gerasimoff J, Griffin C. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:1068. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lefranc F, Brotchi J, Kiss R. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2411. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Abdel-Halim OB, Morikawa T, Ando S, Matsuda H, Yoshikawa M. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:1119. doi: 10.1021/np030529k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Elgorashi EE, Drewes SE, van Staden J. Phytochemistry. 1999;52:533. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00433-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Jitsuno M, Yokosuka A, Sakagami H, Mimaki Y. Chem Pharm Bull. 2009;57:1153. doi: 10.1248/cpb.57.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pettit GR, Gaddamidi V, Cragg GM. J Nat Prod. 1984;47:1018. doi: 10.1021/np50036a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elgorashi EE, Drewes SE, van Staden J. Phytochemistry. 2001;56:637. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00433-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Belot N, Rorive S, Doyen I, Lefranc F, Bruyneel E, Dedecker R, Micik S, Brotchi J, Decaestecker C, Salmon I, Kiss R, Camby I. Glia. 2001;36:375. doi: 10.1002/glia.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Branle F, Lefranc F, Camby I, Jeuken J, Geurts-Moespot A, Sprenger S, Sweep F, Kiss R. Cancer. 2002;95:641. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Le Calvé B, Rynkowski M, Le Mercier M, Bruyere C, Lonez C, Gras T, Haibe-Kains B, Bontempi G, Decaestecker C, Ruysschaert JM, Kiss R, Lefranc F. Neoplasia. 2010;12:727. doi: 10.1593/neo.10526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Camby I, Decaestecker C, Lefranc F, Kaltner H, Gabius HJ, Kiss R. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;335:27. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Evidente A, Cicala MR, Randazzo G, Riccio R, Calabrese G, Liso R, Arrigoni O. Phytochemistry. 1983;22:2193. [Google Scholar]; (b) Evidente A, Arrigoni O, Liso R, Calabrese G, Randazzo G. Phytochemistry. 1986;25:2739. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandsmark DK, Zhang H, Hegedus B, Pelletier CL, Weber JD, Gutmann DH. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4790. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abou-Donia AH, Azim AA, El Din AS, Evidente A, Gaber M, Scopa A. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:2139. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Y, Huang SX, Zhao YM, Zhao QS, Sun HD. Helv Chem Acta. 2005;88:2550. [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Belot N, Pochet R, Heizmann CW, Kiss R, Decaestecker C. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1600:74. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(02)00447-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Debeir O, Van Ham P, Kiss R, Decaestecker C. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2005;24:697. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2005.846851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]