Abstract

Hematopoiesis is well-conserved between Drosophila and vertebrates. Similar as in vertebrates, the sites of hematopoiesis shift during Drosophila development. Blood cells (hemocytes) originate de novo during hematopoietic waves in the embryo and in the Drosophila lymph gland. In contrast, the hematopoietic wave in the larva is based on the colonization of resident hematopoietic sites by differentiated hemocytes that arise in the embryo, much like in vertebrates the colonization of peripheral tissues by primitive macrophages of the yolk sac, or the seeding of fetal liver, spleen and bone marrow by hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. At the transition to the larval stage, Drosophila embryonic hemocytes retreat to hematopoietic “niches,” i.e., segmentally repeated hematopoietic pockets of the larval body wall that are jointly shared with sensory neurons and other cells of the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Hemocytes rely on the PNS for their localization and survival, and are induced to proliferate in these microenvironments, expanding to form the larval hematopoietic system. In this process, differentiated hemocytes from the embryo resume proliferation and self-renew, omitting the need for an undifferentiated prohemocyte progenitor. Larval hematopoiesis is the first Drosophila model for blood cell colonization and niche support by the PNS. It suggests an interface where innocuous or noxious sensory inputs regulate blood cell homeostasis or immune responses. The system adds to the growing concept of nervous system dependence of hematopoietic microenvironments and organ stem cell niches, which is being uncovered across phyla.

Keywords: Drosophila larva, hematopoiesis, hematopoietic pocket, hematopoietic stem cell, hemocyte, microenvironment, niche, peripheral nervous system, sensory neuron, tissue macrophage

Drosophila Blood Cell Lineages and Compartments

Drosophila blood cells, or hemocytes, play essential roles in the removal of apoptotic cells, immune responses against pathogens and parasites and the repair of damaged tissue.1-13 Three differentiated blood cell lineages, and undifferentiated prohemocytes that have progenitor function, are currently being distinguished.13-19 Macrophages, also called plasmatocytes, correspond to the vertebrate myeloid lineage and represent 90–95% of hemocytes at most developmental stages, serving roles in immunity and phagocytosis.3,13,14,16 Invertebrate-specific crystal cells mediate melanization reactions in the embryo and larva,13-16,20 and lamellocytes are induced by specific immune challenges in the larva to wrap large immune targets.7,16,21-23 Several transcription factors and signaling pathways, many of which are conserved in vertebrates, play roles in the specification, differentiation, maintenance and functional responses of hemocytes.18,20,22,24-49

During development, Drosophila blood cells are supplied by a number of hematopoietic tissues to meet the demand during normal homeostasis and challenges such as infection, infestation or stress.18,32,42 Each of these hematopoietic waves follows its own mechanisms, based either on the de novo generation of blood cells, or the recruitment of existing blood cells by colonization of hematopoietic microenvironments.

Hematopoietic Waves Based on De Novo Blood Cell Generation

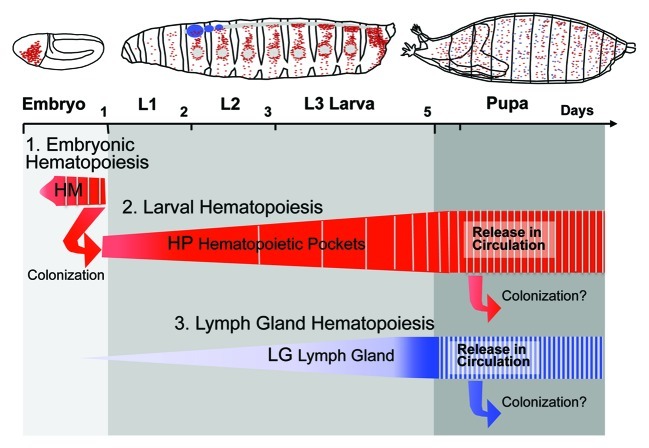

The initial wave of Drosophila hematopoiesis takes place in the embryo (Fig. 1). Hemocytes originate from the procephalic mesoderm, forming undifferentiated progenitor cells, or prohemocytes, which undergo a series of four rapid cell divisions during embryonic stages 8–11.3,50 Subsequently, with the exception of about 5% of the cells that differentiate into crystal cells and retain proliferative capacity,20 these cells stop proliferating and switch to a differentiation program, maturing toward plasmatocyte lineage.3 As plasmatocytes differentiate, they disperse all over the embryo, migrating initially on defined paths.8,10,51 Therefore, stage 11–16 embryos comprise a developmentally fixed number of 600–700 hemocytes, ~90% of which differentiate into plasmatocytes.3,10,35

Figure 1. Hematopoietic waves in Drosophila. Timeline of hematopoietic waves in the Drosophila embryo and larva. Embryonic and lymph gland hematopoiesis are based on the de novo generation of blood cells, while larval hematopoiesis is founded by embryonic hemocytes that colonize hematopoietic pockets of the larval body wall. Vertical hatching indicates release of hemocytes from hematopoietic sites. Note progressive release of larval hemocytes into circulation over the course of larval development. HM, embryonic head mesoderm; HP, larval hematopoietic pockets; LG, lymph gland.

An independent set of blood cells originates from the lymph gland (LG), which develops from an embryonic anlage that grows and matures over the course of larval development and supplies hemocytes at the beginning of metamorphosis,7,13,16,52,53 corresponding to the third wave of hematopoiesis on the developmental timeline of Drosophila (Fig. 1). The LG is developmentally and physically associated with the dorsal vessel,54 a circulatory organ with heart-like functions. LG and dorsal vessel arise from a common hemangioblast progenitor,54 similar to the differentiation of hematopoietic and endothelial cells from a hemangioblast progenitor that emerges from the primitive streak during mammalian development.55,56 The LG is organized into a central medulla of immature, tightly packed prohemocyte progenitors, a peripheral cortical zone of hemocytes that differentiate into plasmatocytes and crystal cells and show increased proliferation, and the posterior signaling center, a microenvironment that controls hemocyte progenitor maintenance and differentiation.22,38,43,52,57 With the exception of severe immune challenges, LG hemocytes do not play roles in the immune or phagocytic functions in the larva,16,22,53 but are released at the beginning of pupariation.53 Thus, a separate set of “larval hemocytes” is active during larval development.23,58

Larval Hematopoiesis: A Wave of Macrophage Expansion Initiated by Blood Cell Colonization

Larval hematopoiesis fills the developmental gap between embryonic hematopoiesis and the release of LG hemocytes at the onset of metamorphosis (Fig. 1).13,16,18,58 Only recently, larval hematopoiesis has been recognized to be initiated through the colonization of hematopoietic microenvironments by existing blood cells, rather than involving the de novo formation of prohemocytes or differentiation of existing progenitors, as was evidenced by extensive lineage tracing and functional approaches.58 Differentiated hemocytes of the embryo are being carried over to the larval stage, colonize segmentally repeated epidermal-muscular (hematopoietic) pockets (Fig. 2) and proliferate in these locations,58 explaining why embryonic hemocytes persist into postembryonic stages.59 Interestingly, after a period of quiescence, and reduction in number in the late-stage embryo (You Bin Lin and K.B.),3,16,58 these hemocytes re-enter, or proceed in, the cell cycle and expand from ~300 at the beginning of larval life to more than 5,000 in the third instar larva (You Bin Lin and K.B., unpublished).16,58 While in early larval development most, if not all, hemocytes retreat to hematopoietic pockets, an increasing number of hemocytes circulate in the hemolymph of second and third instar larvae, playing roles in immunosurveillance. Mobilization of hemocytes culminates during the prepupal phase, leaving only a small fraction of hemocytes in resident locations (K.M. and K.B., unpublished).16,41 Throughout larval life, resident hemocytes are in a dynamic steady-state, exchanging between hematopoietic pockets.58 Similar dynamics have been reported for circulating and dorsal vessel-associated larval hemocytes.60,61 Resident hemocytes can be dispersed by mechanical manipulation, which is followed by their spontaneous return, or “homing,” to hematopoietic pockets in an hour or less, suggesting that the microenvironment has attractive and/or specific adhesive properties.58

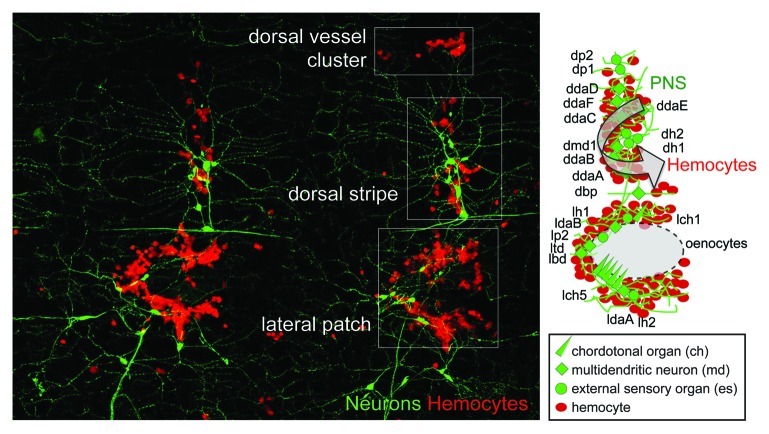

Figure 2. The PNS as hematopoietic microenvironment. (A) Co-labeling of neurons (21–7-GAL4, UAS-CD8-GFP, green),63 and hemocytes (Hml∆-DsRed, red),58 located in the hematopoietic pockets of a filleted 3rd instar larva, anterior left, dorsal up. Two larval abdominal segments showing hemocytes colocalizing with the lateral and dorsal PNS clusters, forming the ‘lateral patch’ and ‘dorsal stripe’. (B) Model of a lateral patch and dorsal stripe. Arrow represents attractive and inductive cues provided by cells of the PNS that support larval hemocytes.

The Nervous System as Microenvironment in Larval Hematopoiesis

Searching for the attractive and inductive constituents of the larval hematopoietic microenvironment, a central functional role of the peripheral nervous system (PNS), was identified.58 The larval PNS consists of segmentally repeated ventral, lateral and dorsal neuron clusters, which sense intrinsic and environmental innocuous and noxious stimuli, such as mechanical strain and movement, temperature, chemicals and light.62-66 Each segment contains a stereotyped cluster of chordotonal organs (ch), external sensory organs (es) and multidendritc neurons (md),67 which extend dendritic processes into all areas of the larval body wall68-70 and project axons ventrally to the brain.69,71,72 Resident hemocytes tightly associate with the cell bodies and extensions of several neuron types in the lateral and dorsal PNS clusters, which jointly localize to hematopoietic pockets, forming the “lateral patch” and “dorsal stripe” of hemocytes (Fig. 2).58 Lateral patches form around clusters of oenocytes, metabolically active cells with similarity to vertebrate hepatocytes,73 which, however, are not essential for hemocyte attraction.58 In contrast, larval hemocytes functionally depend on the PNS as attractive and trophic microenvironment: Atonal (ato) mutant,74,75 or genetically neuron-ablated larvae, deficient for chordotonal organs and few md neurons, show a progressive apoptotic decline in hemocytes and an incomplete resident hemocyte pattern.58 Complementary to this, supernumerary peripheral neurons induced by ectopic expression of the proneural gene scute (sc) can misdirect hemocytes to these ectopic locations.58 Since the PNS contains several neuron populations that are distinct by function and lineage,67,76,77 it will be interesting to dissect functional requirements and potential regulatory connections through neurons and/or their tightly associated glia or support cells.78,79 Since the PNS has a prime function in detecting innocuous and noxious stimuli, and hemocytes become rapidly activated and mobilized for tissue repair and immune functions after an assault,8,9,60,80,81 it is interesting to speculate that the anatomical and functional connection of the PNS with blood cells may coordinate developmental hematopoiesis, homeostasis and immune responses in the Drosophila larva. Similar mechanisms of blood cell colonization, and potentially regulation, could also play roles in post-larval hematopoiesis.

Parallels with Mammalian Systems

Hematopoiesis in the Drosophila larva and vertebrates show numerous parallels. In vertebrates, seeding of hematopoietic sites through colonization by blood cells occurs at multiple times during development. Primitive macrophages of the yolk sac give rise to many types of tissue macrophages, such as the microglia of the brain,82-85 dendritic cells of the skin, Kupffer cells of the liver and resident macrophages of the pancreas, lung, spleen and kidney,86 and also differentiated blood cells from other sources, such as monocytes from fetal liver, seed certain tissue macrophage populations.87 Similarly, AGM (aorta gonad mesonephros) -derived hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) engraft the fetal liver, and, later on, the thymus, spleen and bone marrow,88-90 and committed T-cell progenitors from the thymus seed primary lymphoid organs such as the gut.91

Blood cells that give rise to a hematopoietic population typically require an appropriate microenvironment, or niche, which provides signals that ensure their survival, maintenance, controlled proliferation and differentiation. For example, the mammalian bone marrow niche relies on sympathetic nerves and their associated glia, mesenchymal stem cells and many other cell types that contribute to the hematopoietic microenvironment.92-96 Likewise, tissue macrophages are attracted to and maintained by specific microenvironments,84,86,97-102 and peripheral niches attract and support hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in tissue repair, revascularization and tumorigenesis.96,103,104 During development and in adulthood, murine hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells cycle between resident hematopoietic sites, peripheral blood and other tissues.89,105 Egress and homing are governed by various signaling systems including G-CSF/G-CSFR, CXCL12/CXCR4 and -7, Slit2/Robo4 and Sphingosine 1-phosphate/S1P receptor.92,103,104,106-109

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) is an essential part of the microenvironment in a variety of vertebrate target tissues, including hematopoietic and immune organs,93,110-112 liver113 and endocrine pancreas.114,115 In the vertebrate bone marrow, sympathetic nerves and their associated glia regulate hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) localization, proliferation and maintenance.93,94,110,111,116,117 Communication takes place through direct stimulation of β-adrenergic and dopaminergic receptors on HSCs117 and indirectly, through sympathetic β-adrenergic signals that suppress stromal cells of the bone marrow niche to engage in CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling with HSCs.93,110 Further, glia of the PNS also play important roles, mediating localized activation of TGF-β that promotes HSC maintenance.94,95 Immune responses in lymphocytes and myeloid cells may be regulated via direct contacts with nerve terminals,112,118,119 and neural regulation also governs immune responses in C. elegans,120,121 providing further support that PNS microenvironments in the immune system and hematopoietic sites are widely conserved across phyla. Besides such local regulation by the PNS, hematopoiesis and immunity are further regulated by systemic signals from the central nervous system and, in vertebrates, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.48,122-125

Drosophila larval hematopoiesis sheds a new evolutionary perspective on the two myeloid systems in vertebrates, i.e., myeloid cells that derive from HSCs and the self-renewing tissue macrophages.82,84,87 Much like Drosophila larval hemocytes, vertebrate tissue macrophages expand within local microenvironments.82,84,86,97,99 However, compared with the systemic functions of Drosophila larval hemocytes,16,23,60 vertebrate tissue macrophages may have evolved to adopt more restricted, tissue-specific roles.126-128

Outlook

The optically transparent and genetically tractable Drosophila larva provides a powerful system to study principles of nervous system-hematopoietic regulation. Drosophila sensory neurons comprise a major part of the larval hematopoietic niche, suggesting an interface that could link innocuous or noxious stimuli with blood cell homeostasis and immune responses. It will be interesting to investigate further whether, in vertebrates, sensory innervation in the proximity of tissue macrophages129 and in microenvironments of HSCs in the bone marrow and lymph nodes118,119,130 serve similar functions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brandy Alexander for expert technical support and critical reading of the manuscript. Work reviewed in this article was supported by a HFSP postdoctoral fellowship (K.M.), Sandler Foundation Startup, Broad Research Incubator, Hellman Fellows and PBBR awards (K.B.), and was in part conducted in a facility constructed with support from the Research Facilities Improvement Program, Grant number C06-RR16490 from the NCRR/NIH. We apologize to those authors whose work was accidentally not cited or was not cited individually.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/fly/article/22267

References

- 1.Hoffmann JA, Reichhart JM. Drosophila innate immunity: an evolutionary perspective. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:121–6. doi: 10.1038/ni0202-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemaitre B, Hoffmann J. The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:697–743. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tepass U, Fessler LI, Aziz A, Hartenstein V. Embryonic origin of hemocytes and their relationship to cell death in Drosophila. Development. 1994;120:1829–37. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.7.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrams JM, White K, Fessler LI, Steller H. Programmed cell death during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development. 1993;117:29–43. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franc NC, Heitzler P, Ezekowitz RA, White K. Requirement for croquemort in phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in Drosophila. Science. 1999;284:1991–4. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5422.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kocks C, Cho JH, Nehme N, Ulvila J, Pearson AM, Meister M, et al. Eater, a transmembrane protein mediating phagocytosis of bacterial pathogens in Drosophila. Cell. 2005;123:335–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crozatier M, Krzemien J, Vincent A. The hematopoietic niche: a Drosophila model, at last. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1443–4. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.12.4370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stramer B, Wood W, Galko MJ, Redd MJ, Jacinto A, Parkhurst SM, et al. Live imaging of wound inflammation in Drosophila embryos reveals key roles for small GTPases during in vivo cell migration. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:567–73. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brock AR, Babcock DT, Galko MJ. Active cop, passive cop: developmental stage-specific modes of wound-induced blood cell recruitment in Drosophila. Fly (Austin) 2008;2:303–5. doi: 10.4161/fly.7395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wood W, Jacinto A. Drosophila melanogaster embryonic haemocytes: masters of multitasking. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:542–51. doi: 10.1038/nrm2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson RE, Fessler LI, Takagi Y, Blumberg B, Keene DR, Olson PF, et al. Peroxidasin: a novel enzyme-matrix protein of Drosophila development. EMBO J. 1994;13:3438–47. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dushay MS. Insect hemolymph clotting. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:2643–50. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0036-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans CJ, Hartenstein V, Banerjee U. Thicker than blood: conserved mechanisms in Drosophila and vertebrate hematopoiesis. Dev Cell. 2003;5:673–90. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rizki TM. The circulatory system and associated cells and tissues. In 'The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila', (M Ashburner and TRF Wright, Edts), Academic Press, New York 1978; 2b:397-452. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shrestha R, Gateff E. Ultrastructure and cytochemistry of the cell types in the larval hematopoietic organs and hemolymph of Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Growth Differ. 1982;24:65–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.1982.00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanot R, Zachary D, Holder F, Meister M. Postembryonic hematopoiesis in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 2001;230:243–57. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurucz E, Váczi B, Márkus R, Laurinyecz B, Vilmos P, Zsámboki J, et al. Definition of Drosophila hemocyte subsets by cell-type specific antigens. Acta Biol Hung. 2007;58(Suppl):95–111. doi: 10.1556/ABiol.58.2007.Suppl.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartenstein V. Blood cells and blood cell development in the animal kingdom. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:677–712. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010605.093317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ribeiro C, Brehélin M. Insect haemocytes: what type of cell is that? J Insect Physiol. 2006;52:417–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lebestky T, Chang T, Hartenstein V, Banerjee U. Specification of Drosophila hematopoietic lineage by conserved transcription factors. Science. 2000;288:146–9. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rizki TM, Rizki RM. Lamellocyte differentiation in Drosophila larvae parasitized by Leptopilina. Dev Comp Immunol. 1992;16:103–10. doi: 10.1016/0145-305X(92)90011-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krzemień J, Dubois L, Makki R, Meister M, Vincent A, Crozatier M. Control of blood cell homeostasis in Drosophila larvae by the posterior signalling centre. Nature. 2007;446:325–8. doi: 10.1038/nature05650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Márkus R, Laurinyecz B, Kurucz E, Honti V, Bajusz I, Sipos B, et al. Sessile hemocytes as a hematopoietic compartment in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4805–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801766106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernardoni R, Vivancos V, Giangrande A. glide/gcm is expressed and required in the scavenger cell lineage. Dev Biol. 1997;191:118–30. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Govind S. Control of development and immunity by rel transcription factors in Drosophila. Oncogene. 1999;18:6875–87. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fossett N, Schulz RA. Functional conservation of hematopoietic factors in Drosophila and vertebrates. Differentiation. 2001;69:83–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2001.690202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alfonso TB, Jones BW. gcm2 promotes glial cell differentiation and is required with glial cells missing for macrophage development in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 2002;248:369–83. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho NK, Keyes L, Johnson E, Heller J, Ryner L, Karim F, et al. Developmental control of blood cell migration by the Drosophila VEGF pathway. Cell. 2002;108:865–76. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00676-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munier AI, Doucet D, Perrodou E, Zachary D, Meister M, Hoffmann JA, et al. PVF2, a PDGF/VEGF-like growth factor, induces hemocyte proliferation in Drosophila larvae. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:1195–200. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duvic B, Hoffmann JA, Meister M, Royet J. Notch signaling controls lineage specification during Drosophila larval hematopoiesis. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1923–7. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Remillieux-Leschelle N, Santamaria P, Randsholt NB. Regulation of larval hematopoiesis in Drosophila melanogaster: a role for the multi sex combs gene. Genetics. 2002;162:1259–74. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.3.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evans CJ, Banerjee U. Transcriptional regulation of hematopoiesis in Drosophila. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2003;30:223–8. doi: 10.1016/S1079-9796(03)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fossett N, Hyman K, Gajewski K, Orkin SH, Schulz RA. Combinatorial interactions of serpent, lozenge, and U-shaped regulate crystal cell lineage commitment during Drosophila hematopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11451–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1635050100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asha H, Nagy I, Kovacs G, Stetson D, Ando I, Dearolf CR. Analysis of Ras-induced overproliferation in Drosophila hemocytes. Genetics. 2003;163:203–15. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brückner K, Kockel L, Duchek P, Luque CM, Rørth P, Perrimon N. The PDGF/VEGF receptor controls blood cell survival in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2004;7:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zettervall CJ, Anderl I, Williams MJ, Palmer R, Kurucz E, Ando I, et al. A directed screen for genes involved in Drosophila blood cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14192–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403789101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishimaru S, Ueda R, Hinohara Y, Ohtani M, Hanafusa H. PVR plays a critical role via JNK activation in thorax closure during Drosophila metamorphosis. EMBO J. 2004;23:3984–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mandal L, Martinez-Agosto JA, Evans CJ, Hartenstein V, Banerjee UA. A Hedgehog- and Antennapedia-dependent niche maintains Drosophila haematopoietic precursors. Nature. 2007;446:320–4. doi: 10.1038/nature05585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferjoux G, Augé B, Boyer K, Haenlin M, Waltzer LA. A GATA/RUNX cis-regulatory module couples Drosophila blood cell commitment and differentiation into crystal cells. Dev Biol. 2007;305:726–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Minakhina S, Druzhinina M, Steward R. Zfrp8, the Drosophila ortholog of PDCD2, functions in lymph gland development and controls cell proliferation. Development. 2007;134:2387–96. doi: 10.1242/dev.003616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stofanko M, Kwon SY, Badenhorst P. A misexpression screen to identify regulators of Drosophila larval hemocyte development. Genetics. 2008;180:253–67. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.089094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martinez-Agosto JA, Mikkola HK, Hartenstein V, Banerjee U. The hematopoietic stem cell and its niche: a comparative view. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3044–60. doi: 10.1101/gad.1602607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sinenko SA, Mandal L, Martinez-Agosto JA, Banerjee U. Dual role of wingless signaling in stem-like hematopoietic precursor maintenance in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2009;16:756–63. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clark RI, Woodcock KJ, Geissmann F, Trouillet C, Dionne MS. Multiple TGF-β superfamily signals modulate the adult Drosophila immune response. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1672–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mondal BC, Mukherjee T, Mandal L, Evans CJ, Sinenko SA, Martinez-Agosto JA, et al. Interaction between differentiating cell- and niche-derived signals in hematopoietic progenitor maintenance. Cell. 2011;147:1589–600. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mukherjee T, Kim WS, Mandal L, Banerjee U. Interaction between Notch and Hif-alpha in development and survival of Drosophila blood cells. Science. 2011;332:1210–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1199643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minakhina S, Tan W, Steward R. JAK/STAT and the GATA factor Pannier control hemocyte maturation and differentiation in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 2011;352:308–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shim J, Mukherjee T, Banerjee U. Direct sensing of systemic and nutritional signals by haematopoietic progenitors in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:394–400. doi: 10.1038/ncb2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pennetier D, Oyallon J, Morin-Poulard I, Dejean S, Vincent A, Crozatier M. Size control of the Drosophila hematopoietic niche by bone morphogenetic protein signaling reveals parallels with mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:3389–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109407109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rehorn KP, Thelen H, Michelson AM, Reuter R. A molecular aspect of hematopoiesis and endoderm development common to vertebrates and Drosophila. Development. 1996;122:4023–31. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.4023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siekhaus D, Haesemeyer M, Moffitt O, Lehmann R. RhoL controls invasion and Rap1 localization during immune cell transmigration in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:605–10. doi: 10.1038/ncb2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jung SH, Evans CJ, Uemura C, Banerjee U. The Drosophila lymph gland as a developmental model of hematopoiesis. Development. 2005;132:2521–33. doi: 10.1242/dev.01837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grigorian M, Mandal L, Hartenstein V. Hematopoiesis at the onset of metamorphosis: terminal differentiation and dissociation of the Drosophila lymph gland. Dev Genes Evol. 2011;221:121–31. doi: 10.1007/s00427-011-0364-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mandal L, Banerjee U, Hartenstein V. Evidence for a fruit fly hemangioblast and similarities between lymph-gland hematopoiesis in fruit fly and mammal aorta-gonadal-mesonephros mesoderm. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1019–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dzierzak E, Speck NA. Of lineage and legacy: the development of mammalian hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:129–36. doi: 10.1038/ni1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zape JP, Zovein AC. Hemogenic endothelium: origins, regulation, and implications for vascular biology. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:1036–47. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lebestky T, Jung SH, Banerjee U. A Serrate-expressing signaling center controls Drosophila hematopoiesis. Genes Dev. 2003;17:348–53. doi: 10.1101/gad.1052803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Makhijani K, Alexander B, Tanaka T, Rulifson E, Brückner K. The peripheral nervous system supports blood cell homing and survival in the Drosophila larva. Development. 2011;138:5379–91. doi: 10.1242/dev.067322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holz A, Bossinger B, Strasser T, Janning W, Klapper R. The two origins of hemocytes in Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:4955–62. doi: 10.1242/dev.00702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Babcock DT, Brock AR, Fish GS, Wang Y, Perrin L, Krasnow MA, et al. Circulating blood cells function as a surveillance system for damaged tissue in Drosophila larvae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10017–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709951105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Welman A, Serrels A, Brunton VG, Ditzel M, Frame MC. Two-color photoactivatable probe for selective tracking of proteins and cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11607–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Im SH, Galko MJ. Pokes, sunburn, and hot sauce: Drosophila as an emerging model for the biology of nociception. Dev Dyn. 2012;241:16–26. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Song W, Onishi M, Jan LY, Jan YN. Peripheral multidendritic sensory neurons are necessary for rhythmic locomotion behavior in Drosophila larvae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5199–204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700895104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xiang Y, Yuan Q, Vogt N, Looger LL, Jan LY, Jan YN. Light-avoidance-mediating photoreceptors tile the Drosophila larval body wall. Nature. 2010;468:921–6. doi: 10.1038/nature09576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hughes CL, Thomas JB. A sensory feedback circuit coordinates muscle activity in Drosophila. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;35:383–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tracey WD, Jr., Wilson RI, Laurent G, Benzer S. painless, a Drosophila gene essential for nociception. Cell. 2003;113:261–73. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bodmer R, Carretto R, Jan YN. Neurogenesis of the peripheral nervous system in Drosophila embryos: DNA replication patterns and cell lineages. Neuron. 1989;3:21–32. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gao FB, Brenman JE, Jan LY, Jan YN. Genes regulating dendritic outgrowth, branching, and routing in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2549–61. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grueber WB, Jan LY, Jan YN. Tiling of the Drosophila epidermis by multidendritic sensory neurons. Development. 2002;129:2867–78. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.12.2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grueber WB, Ye B, Moore AW, Jan LY, Jan YN. Dendrites of distinct classes of Drosophila sensory neurons show different capacities for homotypic repulsion. Curr Biol. 2003;13:618–26. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zlatic M, Li F, Strigini M, Grueber W, Bate M. Positional cues in the Drosophila nerve cord: semaphorins pattern the dorso-ventral axis. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grueber WB, Ye B, Yang CH, Younger S, Borden K, Jan LY, et al. Projections of Drosophila multidendritic neurons in the central nervous system: links with peripheral dendrite morphology. Development. 2007;134:55–64. doi: 10.1242/dev.02666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gutierrez E, Wiggins D, Fielding B, Gould AP. Specialized hepatocyte-like cells regulate Drosophila lipid metabolism. Nature. 2007;445:275–80. doi: 10.1038/nature05382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jarman AP, Grau Y, Jan LY, Jan YN. atonal is a proneural gene that directs chordotonal organ formation in the Drosophila peripheral nervous system. Cell. 1993;73:1307–21. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90358-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jarman AP, Sun Y, Jan LY, Jan YN. Role of the proneural gene, atonal, in formation of Drosophila chordotonal organs and photoreceptors. Development. 1995;121:2019–30. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.7.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jan YN, Jan LY. Branching out: mechanisms of dendritic arborization. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:316–28. doi: 10.1038/nrn2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Orgogozo V, Grueber WB. FlyPNS, a database of the Drosophila embryonic and larval peripheral nervous system. BMC Dev Biol. 2005;5:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Banerjee S, Bhat MA. Glial ensheathment of peripheral axons in Drosophila. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:1189–98. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hartenstein V. Morphological diversity and development of glia in Drosophila. Glia. 2011;59:1237–52. doi: 10.1002/glia.21162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Agaisse H, Petersen UM, Boutros M, Mathey-Prevot B, Perrimon N. Signaling role of hemocytes in Drosophila JAK/STAT-dependent response to septic injury. Dev Cell. 2003;5:441–50. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00244-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wood W, Faria C, Jacinto A. Distinct mechanisms regulate hemocyte chemotaxis during development and wound healing in Drosophila melanogaster. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:405–16. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Herbomel P, Thisse B, Thisse C. Ontogeny and behaviour of early macrophages in the zebrafish embryo. Development. 1999;126:3735–45. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alliot F, Godin I, Pessac B. Microglia derive from progenitors, originating from the yolk sac, and which proliferate in the brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;117:145–52. doi: 10.1016/S0165-3806(99)00113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, Nandi S, See P, Gokhan S, et al. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science. 2010;330:841–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1194637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Svahn AJ, Graeber MB, Ellett F, Lieschke GJ, Rinkwitz S, Bennett MR, et al. Development of ramified microglia from early macrophages in the zebrafish optic tectum. Dev Neurobiol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/dneu.22039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schulz C, Gomez Perdiguero E, Chorro L, Szabo-Rogers H, Cagnard N, Kierdorf K, et al. A lineage of myeloid cells independent of Myb and hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2012;336:86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1219179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hoeffel G, Wang Y, Greter M, See P, Teo P, Malleret B, et al. Adult Langerhans cells derive predominantly from embryonic fetal liver monocytes with a minor contribution of yolk sac-derived macrophages. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1167–81. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cumano A, Godin I. Ontogeny of the hematopoietic system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:745–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Laird DJ, von Andrian UH, Wagers AJ. Stem cell trafficking in tissue development, growth, and disease. Cell. 2008;132:612–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bertrand JY, Traver D. Hematopoietic cell development in the zebrafish embryo. Curr Opin Hematol. 2009;16:243–8. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32832c05e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lambolez F, Arcangeli ML, Joret AM, Pasqualetto V, Cordier C, Di Santo JP, et al. The thymus exports long-lived fully committed T cell precursors that can colonize primary lymphoid organs. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:76–82. doi: 10.1038/ni1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ehninger A, Trumpp A. The bone marrow stem cell niche grows up: mesenchymal stem cells and macrophages move in. J Exp Med. 2011;208:421–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Méndez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, Mazloom AR, Macarthur BD, Lira SA, et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466:829–34. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yamazaki S, Ema H, Karlsson G, Yamaguchi T, Miyoshi H, Shioda S, et al. Nonmyelinating Schwann cells maintain hematopoietic stem cell hibernation in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2011;147:1146–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brückner K. Blood cells need glia, too: a new role for the nervous system in the bone marrow niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:493–5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Carlesso N, Cardoso AA. Stem cell regulatory niches and their role in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2010;17:281–6. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32833a25d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ajami B, Bennett JL, Krieger C, Tetzlaff W, Rossi FM. Local self-renewal can sustain CNS microglia maintenance and function throughout adult life. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1538–43. doi: 10.1038/nn2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chorro L, Geissmann F. Development and homeostasis of ‘resident’ myeloid cells: the case of the Langerhans cell. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:438–45. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Merad M, Manz MG, Karsunky H, Wagers A, Peters W, Charo I, et al. Langerhans cells renew in the skin throughout life under steady-state conditions. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1135–41. doi: 10.1038/ni852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cecchini MG, Dominguez MG, Mocci S, Wetterwald A, Felix R, Fleisch H, et al. Role of colony stimulating factor-1 in the establishment and regulation of tissue macrophages during postnatal development of the mouse. Development. 1994;120:1357–72. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.6.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kaplan DH, Li MO, Jenison MC, Shlomchik WD, Flavell RA, Shlomchik MJ. Autocrine/paracrine TGFbeta1 is required for the development of epidermal Langerhans cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2545–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kel JM, Girard-Madoux MJ, Reizis B, Clausen BE. TGF-beta is required to maintain the pool of immature Langerhans cells in the epidermis. J Immunol. 2010;185:3248–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kaplan RN, Psaila B, Lyden D. Niche-to-niche migration of bone-marrow-derived cells. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Adams GB, Scadden DT. The hematopoietic stem cell in its place. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:333–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Massberg S, Schaerli P, Knezevic-Maramica I, Köllnberger M, Tubo N, Moseman EA, et al. Immunosurveillance by hematopoietic progenitor cells trafficking through blood, lymph, and peripheral tissues. Cell. 2007;131:994–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kiel MJ, Morrison SJ. Uncertainty in the niches that maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:290–301. doi: 10.1038/nri2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Méndez-Ferrer S, Chow A, Merad M, Frenette PS. Circadian rhythms influence hematopoietic stem cells. Curr Opin Hematol. 2009;16:235–42. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32832bd0f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Smith-Berdan S, Nguyen A, Hassanein D, Zimmer M, Ugarte F, Ciriza J, et al. Robo4 cooperates with CXCR4 to specify hematopoietic stem cell localization to bone marrow niches. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ratajczak MZ, Kim CH, Abdel-Latif A, Schneider G, Kucia M, Morris AJ, et al. A novel perspective on stem cell homing and mobilization: review on bioactive lipids as potent chemoattractants and cationic peptides as underappreciated modulators of responsiveness to SDF-1 gradients. Leukemia: official journal of the Leukemia Society of America. Leukemia Research Fund, UK. 2012;26:63–72. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Katayama Y, Battista M, Kao WM, Hidalgo A, Peired AJ, Thomas SA, et al. Signals from the sympathetic nervous system regulate hematopoietic stem cell egress from bone marrow. Cell. 2006;124:407–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Méndez-Ferrer S, Lucas D, Battista M, Frenette PS. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature. 2008;452:442–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Straub RH. Complexity of the bi-directional neuroimmune junction in the spleen. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:640–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kiba T. The role of the autonomic nervous system in liver regeneration and apoptosis--recent developments. Digestion. 2002;66:79–88. doi: 10.1159/000065594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Imai J, Katagiri H, Yamada T, Ishigaki Y, Suzuki T, Kudo H, et al. Regulation of pancreatic beta cell mass by neuronal signals from the liver. Science. 2008;322:1250–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1163971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kiba T. Relationships between the autonomic nervous system and the pancreas including regulation of regeneration and apoptosis: recent developments. Pancreas. 2004;29:e51–8. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200408000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yamazaki K, Allen TD. Ultrastructural morphometric study of efferent nerve terminals on murine bone marrow stromal cells, and the recognition of a novel anatomical unit: the “neuro-reticular complex”. Am J Anat. 1990;187:261–76. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001870306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Spiegel A, Shivtiel S, Kalinkovich A, Ludin A, Netzer N, Goichberg P, et al. Catecholaminergic neurotransmitters regulate migration and repopulation of immature human CD34+ cells through Wnt signaling. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1123–31. doi: 10.1038/ni1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Shepherd AJ, Downing JE, Miyan JA. Without nerves, immunology remains incomplete -in vivo veritas. Immunology. 2005;116:145–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mignini F, Streccioni V, Amenta F. Autonomic innervation of immune organs and neuroimmune modulation. Auton Autacoid Pharmacol. 2003;23:1–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-8673.2003.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sun J, Singh V, Kajino-Sakamoto R, Aballay A. Neuronal GPCR controls innate immunity by regulating noncanonical unfolded protein response genes. Science. 2011;332:729–32. doi: 10.1126/science.1203411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhang X, Zhang Y. Neural-immune communication in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:425–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Silverman MN, Pearce BD, Biron CA, Miller AH. Immune modulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis during viral infection. Viral Immunol. 2005;18:41–78. doi: 10.1089/vim.2005.18.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Haddad JJ. On the mechanisms and putative pathways involving neuroimmune interactions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;370:531–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Olefsky JM, Glass CK. Macrophages, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:219–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mora F, Segovia G, Del Arco A, de Blas M, Garrido P. Stress, neurotransmitters, corticosterone and body-brain integration. Brain Res. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Merad M, Ginhoux F, Collin M. Origin, homeostasis and function of Langerhans cells and other langerin-expressing dendritic cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:935–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Geissmann F, Manz MG, Jung S, Sieweke MH, Merad M, Ley K. Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science. 2010;327:656–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1178331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ransohoff RM, Perry VH. Microglial physiology: unique stimuli, specialized responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:119–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Goldstein B. Anatomy of the peripheral nervous system. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2001;12:207–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Nance DM, Sanders VM. Autonomic innervation and regulation of the immune system (1987-2007) Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:736–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]