Abstract

Background

It has been widely established that the conversion of the cellular prion protein (PrPC) into its abnormal isoform (PrPSc) is responsible for the development of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs). However, the knowledge of the detailed molecular mechanisms and direct functional consequences within the cell is rare. In this study, we aimed at the identification of deregulated proteins which might be involved in prion pathogenesis.

Findings

Apolipoprotein E and peroxiredoxin 6 (PRDX6) were identified as upregulated proteins in brains of scrapie-infected mice and cultured neuronal cell lines. Downregulation of PrP gene expression using specific siRNA did not result in a decrease of PRDX6 amounts. Interestingly, selective siRNA targeting PRDX6 or overexpression of PRDX6 controlled PrPC and PrPSc protein amounts in neuronal cells.

Conclusions

Besides its possible function as a novel marker protein in the diagnosis of TSEs, PDRX6 represents an attractive target molecule in putative pharmacological intervention strategies in the future.

Keywords: Peroxiredoxin 6, Prion protein, Scrapie

Findings

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) are fatal neurodegenerative disorders, which include scrapie in sheep, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle, and Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease (CJD) in humans [1]. The molecular hallmark of these disorders is a structural conversion in folding of the normal cellular prion protein (PrPC) into a disease-associated, protease-resistant isoform (PrPSc) [2]. Neuropathological characteristics of these diseases include neuronal loss, vacuolar degeneration, astrogliosis and amyloid plaque formation caused by accumulation of PrPSc[3]. However, the mechanism whereby PrPC → PrPSc conversion triggers cellular neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration is not well understood.

PrPC is a multifunctional plasma membrane glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored protein on a wide range of different cell types where it is involved in adhesion, signal transduction, differentiation, survival or stress protection [4-6]. Obviously, neurodegenerative disorders interconnect several cellular signal transduction pathways to cause oxidative stress in the brain, including increased oxidative damage, impaired mitochondrial function, defects of the proteasome system, the presence of aggregated proteins, and many more [7]. There are a number of cellular antioxidant defenses to convert reactive oxygen species (ROS) into unreactive compounds, e.g. superoxide dismutase (SOD) and the peroxiredoxin (PRDX) family. Proteins of the PRDX family are widely expressed and exhibit crucial protective functions in neurological disorders such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases [8]. Accordingly, upregulation of PRDX protein was observed in the brain of patients with Parkinson and Alzheimer’s disease, and also during experimental prion infection in mice [9-11]. The PRDX family of mammals comprises six isoforms (PRDX1-6), which are classified into the three subgroups typical 2-Cys PRDX (PRDX1–4), atypical 2-Cys PRDX (PRDX5) and 1-Cys PRDX (PRDX6) [12]. Peroxiredoxin 6 is the only 1-Cys member and exhibits bifunctional activities as a glutathione (GSH) peroxidase and calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (PLA2) [13], which might contribute to neurological disorders. In experimental in vivo models for neurological disorders such as Huntington′s disease and scrapie, PRDX1 was slightly enhanced [11]. However, the function of distinct PRDX isoforms in prion diseases has not been investigated.

Upregulation of PRDX6 in scrapie-infected brains

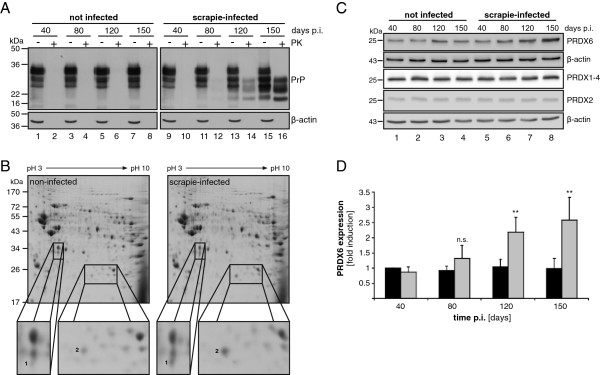

For a better understanding of the proteomic alterations during in vivo prion pathogenesis, C57Bl/6 mice were intracerebrally inoculated with a 10% brain homogenate containing the prion strain 139A (Additional file 1). Mice were sacrificed after 40, 80, 120 and 150 days, and brain homogenates were prepared. To confirm prion infection, PrP expression was analyzed by Western blot (Figure 1A). PrPC was detected in non-infected brain homogenates in equal amounts 40, 80, 120 and 150 days post infection (p.i.) (Figure 1A, lanes 1, 3, 5, 7), while total PrP of scrapie-infected brain homogenates slightly increased during infection (Figure 1A, lanes 9, 11, 13, 15), caused by the accumulation of PrPSc as demonstrated by proteinase K (PK)-digestion (Figure 1A, lanes 10, 12, 14, 16).

Figure 1.

Upregulation of PRDX6 in scrapie-infected mice. (A) C57Bl/6 mice were inoculated intracerebrally with PBS (not infected, lanes 1–8) or 10% brain homogenate of the prion strain 139A (scrapie-infected, lanes 9–16). 40, 80, 120 and 150 days post infection (p.i.) brain homogenates were prepared and incubated with 20 μg/ml proteinase K (+, PK) or left untreated (−) prior to Western blotting. PrP was detected using the 8H4 monoclonal antibody showing the typical migration pattern of PrP and PK-resistant PrPres. β-actin was shown as a loading control. (B) 150 μg protein of brain homogenates were separated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis followed by Coomassie blue staining. Enlarged sections indicate differentially expressed proteins (spots 1 and 2) observed in four tested homogenates. (C) 50 μg protein of brain homogenates were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot. PRDX6, PRDX1-4, PRDX2 and β-actin were detected using specific antibodies. (D) Quantification of protein expression was performed using four independent Western blots detecting PRDX6 (grey bars) and β-actin (black bars) in brain homogenates of four different mice, respectively. PRDX6 expression was by normalized to β-actin (**, p < 0.01, n.s., non-specific)

To identify differentially regulated proteins in scrapie-infected mice, equal protein amounts of brain homogenates were separated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis followed by Coomassie blue staining (Figure 1B). Only two up-regulated protein spots were reproducibly detected in four individual mice infected by scrapie, which were then identified by mass spectrometry (Table 1). Apolipoprotein E was found in three out of four investigated samples, while peroxiredoxin 6 (PRDX6) was identified with an overall sequence coverage of 71.4% in all four tested samples (Table 1). Upregulation of apolipoprotein E has already been described in activated astrocytes in Alzheimer′s and prion disease [14] and is considered as one of the strongest genetic risk factors in Alzheimer disease [15]. Contrastingly, only marginal information is available on the expression of peroxiredoxins in prion disease. Peroxiredoxin protein was preferentially upregulated in astrocytes of prion-infected mouse brains [10], but it remained unknown whether all PRDX family members or a single isoform accumulated. Furthermore, PRDX6 protein expression in astrocytes has already been associated with Alzheimer disease where it might function as an antioxidant enzyme [9] suggesting that PRDX6 might be involved in neurological diseases.

Table 1.

Identification of apolipoprotein E and peroxiredoxin 6 by mass spectrometry

| Spot | Mouse | Acc.nr. | Protein name | Score | Peptide | Sequence coverage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

1 |

P08226 |

Apolipoprotein E OS Mus musculus GN Apoe PE 1 SV 2 |

470.7 |

5 |

19.3 |

| 1 |

3 |

P08226 |

Apolipoprotein E OS Mus musculus GN Apoe PE 1 SV 2 |

220.7 |

3 |

13.5 |

| 1 |

4 |

P08226 |

Apolipoprotein E OS Mus musculus GN Apoe PE 1 SV 2 |

215.3 |

4 |

16.4 |

| 2 |

1 |

O08709 |

Peroxiredoxin 6 OS Mus musculus GN Prd × 6 PE 1 SV 3 |

1023.0 |

10 |

59.4 |

| 2 |

2 |

O08709 |

Peroxiredoxin 6 OS Mus musculus GN Prd × 6 PE 1 SV 3 |

1176.2 |

11 |

69.6 |

| 2 |

3 |

O08709 |

Peroxiredoxin 6 OS Mus musculus GN Prd × 6 PE 1 SV 3 |

1737.0 |

11 |

59.8 |

| 2 | 4 | O08709 | Peroxiredoxin 6 OS Mus musculus GN Prd × 6 PE 1 SV 3 | 779.9 | 7 | 33.5 |

To investigate this in more detail, we followed PRDX6 expression during scrapie infection in mice and compared it with PRDX1-4 amounts by Western blot analyses (Figure 1C). In contrast to non-infected mice (Figure 1C, lane 1–4), the level of PRDX6 steadily increased within 150 days post infection (Figure 1C, lane 5–8). This appears to be highly specific, since amounts of PRDX1-4 or PRDX2 did not change during infection (Figure 1C, lane 5–8). Although we cannot exclude the possibility that PRDX1, 3 or 4 of the 2-Cys PRDX subgroup were slightly regulated, it is obvious that PRDX6 was strongly affected in scrapie-infected mice brains. Quantification of PRDX6 protein expression in brains of four individual mice at each time point after infection indicated that the observed effect was statistically significant and reproducibly observed in scrapie-infected mice (Figure 1D).

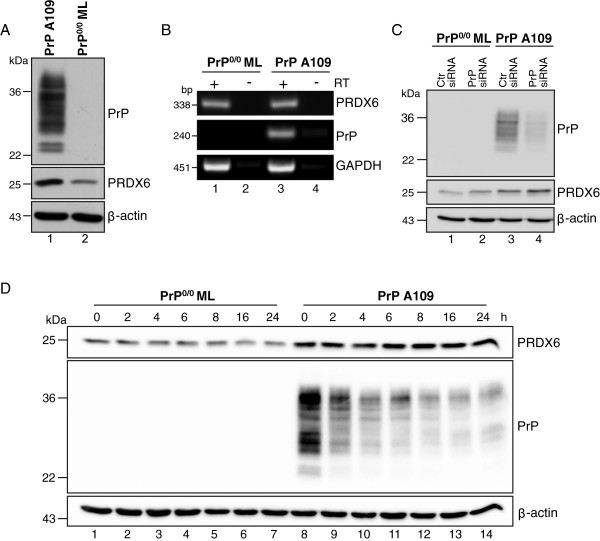

Expression of peroxiredoxin 6 in PrP deficient and PrPC expressing neuronal precursor cells

To investigate PRDX6 expression in more detail, endogenous PRDX6 expression in PrP-deficient and PrPC-expressing cells was analyzed. The immortalized neuronal precursor cell line PrP0/0 ML derived from PrP0/0 ZrchI mice was stably transfected with wild type murine PrP (PrP A109) [16]. Western blots of these cell lines were performed for detection of PrP and PRDX6. As expected, PrP A109 cells expressed PrPC, whereas the PrP0/0 ML cells did not (Figure 2A, upper panel). Corresponding to in vivo studies, PRDX6 expression was increased in PrP A109 cells (Figure 2A, middle panel) while detection of β-actin indicated equal protein loading (Figure 2A, lower panel). Analyzing mRNA synthesis of prdx6 and prnp, no significant alterations were observed indicating that PRDX6 protein expression was not transcriptionally dependent on PrP (Figure 2B). To clarify whether PrP protein expression led to PRDX6 accumulation, PrP was downregulated using specific siRNAs and the amount of PRDX6 protein was analyzed by Western blotting. Interestingly, successful downregulation of PrP (Figure 2C, lane 4) did not result in a detectable decrease in PRDX6 protein amount (Figure 2C, lane 4). This finding was further supported by the inhibition of protein translation using cycloheximide. Twenty-four hours incubation of the cells with cycloheximide led to a drastic decrease in PrP expression, while leaving PRDX6 protein amounts unaffected (Figure 2D, lanes 8–14). Although downregulation of PrP was not complete, these data imply that enhanced PrP expression does not induce PRDX6 expression and that PRXD6 is highly stable in neuronal cells.

Figure 2.

PRDX6 upregulation is not strictly dependent on PrP expression. (A) Lysates of PrP-deficient (PrP0/0) and PrPC-expressing cells (PrP) were analyzed for PrPC, PRDX6 and β-actin. (B) Semi-quantitative PCR was performed with specific primers for murine prdx6, prnp and gapdh with (+) or without (−) reverse transcriptase (RT). (C) PrP0/0 and PrP cells were transfected with control siRNA (Ctr. siRNA) or siRNAs specific for murine PrP (PrP siRNA). 72 h after transfection cell lysates were prepared and Western blot analysis using the specific anti-PrP antibody SAF32 and anti-PRDX6 antibody were performed. β-actin was shown as a loading control. (D) Cells were incubated with 5 μg/ml cycloheximide and lysed after indicated time points. Equal amounts of cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and detection of PRDX6, PrP and β-actin was carried out using specific antibodies

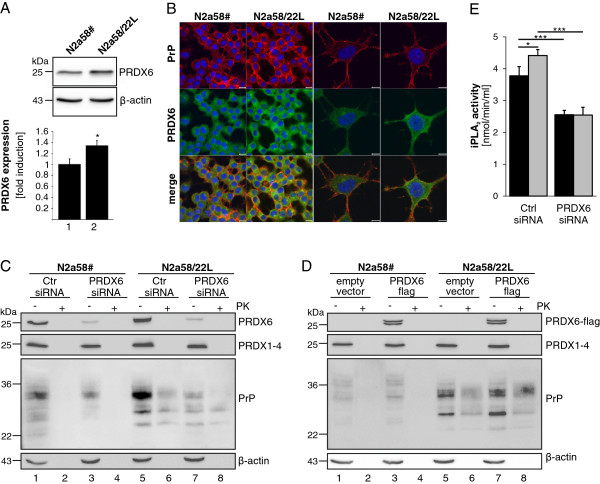

PRDX6 induces upregulation of PrP in neuronal cells

Next, we aimed at the investigation of PRDX6 expression in scrapie-infected neuronal cells. Uninfected PrPC expressing N2a58# cells were compared to scrapie-infected N2a58/22L cells. Correspondingly to scrapie-infected mice, an upregulation of PRDX6 was observed in scrapie-infected N2a58/22L cells as shown by Western blot analysis (Figure 3A, upper panel). Signal intensities from four independent experiments were quantified and expressed as fold PRXD6 expression normalized to β-actin expression (Figure 3A, lower panel). Increased PRXD6 protein amounts were also detected by immunofluorescence analyses underlining enhanced protein occurrence in the cytoplasm, while PrP was mainly localized at the plasma membrane (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

PRDX6 induces PrP upregulation. (A) Detection of endogenous PRDX6 in uninfected N2a58# and scrapie-infected N2a58/22L cells was performed by Western blot using specific anti-PRDX6 and anti-β-actin antibodies (upper panel). Quantification of PRDX6 expression was carried out of four independent experiments (lower panel; *, p < 0.05). (B) PrP (red) and PRDX6 (green) in uninfected N2a58# and scrapie-infected N2a58/22L cells were detected by laser scanning microscopy using PrP-specific 6H4 and PRDX6 antibodies. Nuclei (blue) were stained by DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm (left panel); scale bar, 5 μm. (C) Downregulation of PRDX6 was performed by reverse transfection of a control siRNA (Ctr. siRNA) or a combination of two siRNAs specific for PRDX6 (PRDX6 siRNA). 48 h after transfection cells were lysed and either incubated with 20 μg/ml PK (+) or left untreated (−). Western blot was performed using specific antibodies against PRDX6, PRDX1-4, PrP (8H4) and anti-β-actin antibodies. (D) Cells were transfected with an empty vector control or a PRDX6 expression plasmid (PRDX6-flag) and lysed 24 h after transfection. Equal amounts of cell lysates were treated with PK (+) or left untreated (−) following SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using anti-flag, anti-PRDX6, anti-PRDX1-4, anti-PrP (8H4) and anti-β-actin antibodies. (E) The activity of iPLA2 was analyzed in N2a58# (black bars) and scrapie-infected N2a58/22L cells (grey bars), which were either treated with siRNA targeting PRDX6 or control siRNA (Ctrl) (*, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001)

Since PRDX6 was upregulated in PrPC-expressing and PrPSc-infected cells, but not in cells in which PrPC expression was downregulated, we tested the hypothesis if PRDX6 is involved in PrP upregulation in turn. In N2a58# and N2a58/22L cells PRDX6 was successfully downregulated using PRDX6 specific siRNA that did not affect PRDX1-4 expression. Interestingly, PrPC in N2a58# cells was slightly decreased and PK-resistant PrPSc was strongly reduced in N2a58/22L upon siRNA treatment to inhibit PRXD6 expression (Figure 3C). These data led to the suggestion that there is a functional connection between PrP and PRDX6 expression. Therefore, flag-tagged PRDX6 was overexpressed in N2a58# and N2a58/22L cells and the amount of PrPC and PrPSc was examined. Overexpression of PRDX6-flag had no influence on expression of PRDX1-4 (Figure 3D). However, PRDX6-flag resulted in a slightly increased amount of PrPC in uninfected N2a58# (Figure 3D, lanes 1–4) and subsequently to an obvious accumulation of PK-sensitive PrPC and PK-resistant PrPSc in infected N2a58/22L (Figure 3D, lanes 5–8). PRDX6 exhibits a calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2) activity [17]. In N2a58/22L cells, iPLA2 activity was significantly increased compared to N2a58# cells. Importantly the difference was completely diminished after down-regulation of PRDX6 in both cell lines (Figure 3E). In conclusion, these results suggest that the expression level and activity of PRDX6 might be involved in the control of the level of PrPC and subsequently PrPSc conversion.

In this study, enhanced amounts of PRDX6 was selectively identified in brains of prion-infected mice and neuronal cell lines concomitant with an increased amount of PrPC and consequently of PrPSc. This interaction appears very complex, since PrPC expression in PrP knock-out cells has also been observed to increase the amount of PRDX6 in turn, but downregulation of PrP did not alter PRDX6 appearance. This effect could be explained by the observation that the PRDX6 protein was more stable than PrP. Hence, the molecular basis for this phenomenon remains unknown, but might indicate a complex “tandem”-regulation of PRDX6 and PrP.

PRDX6 is a moonlighting protein containing peroxidase and PLA2 activities [18]. Specific pharmacological inhibitors for cellular studies are not available, but it is tempting to speculate whether PRDX6 activities are involved in PrP regulation. In fact, data are accumulating that PLA2 contributes to prion diseases. Functionally, PLA2 is an important promoter of phospholipid metabolism and cleaves membrane phospholipids to produce arachidonic acid and lysophopholipids as major products [19]. Under normal conditions, arachidonic acid is either re-incorporated into phospholipids, converted to inflammatory mediators in the brain or modulates neuronal functions [20]. It has been demonstrated that PrPSc and the neurotoxic PrP106-126 prion peptide stimulated the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor [21], which is accompanied by the release of arachidonic acid, suggesting an involvement of PLA2 in prion pathogenesis [22]. This has been supported by neuronal cell culture studies showing that PLA2 is activated by glycosylphosphatidylinositols (GPIs) isolated from PrPC and PrPSc[23]. Interestingly, treatment of CJD using the non-specific PLA2 inhibitor quinacrine resulted in an inhibition of PrPSc formation [24] and reduced toxicity of PrP106-126 [25]. Together with our study, those data point to PRDX6 activities as new important players in the pathogenesis of prion diseases.

Abbreviations

PRDX6: Peroxiredoxin 6; PrP: Prion protein.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

WW: performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. AR: conducted and interpreted mass spectrometry analysis. PH: performed the animal experiments. JL: participated in the design of the study and the interpretation of the results. SW: conceived of the study, and participated in design and coordination and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Wagner et al., Cell Communication and Signaling.

Contributor Information

Wibke Wagner, Email: wagner@bio.tu-darmstadt.de.

Andreas Reuter, Email: andreas.reuter@pei.de.

Petra Hüller, Email: petra.hueller@gmx.de.

Johannes Löwer, Email: johannes.loewer@pei.de.

Silja Wessler, Email: silja.wessler@sbg.ac.at.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Edgar Holznagel for valuable discussions and Kay-Martin Hanschmann for statistical analysis.

References

- Prusiner SB. Prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13363–13383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–144. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. Etiology and pathogenesis of prion diseases. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:785–811. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins VR, Linden R, Prado MA, Walz R, Sakamoto AC, Izquierdo I, Brentani RR. Cellular prion protein: on the road for functions. FEBS Lett. 2002;512:25–28. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westergard L, Christensen HM, Harris DA. The cellular prion protein (PrP(C)): its physiological function and role in disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:629–644. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner W, Ajuh P, Lower J, Wessler S. Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of prion-infected neuronal cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2010;8:28. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-8-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: where are we now? J Neurochem. 2006;97:1634–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Santo A, Li Y. The antioxidant enzyme peroxiredoxin and its protective role in neurological disorders. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2012;237:143–149. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2011.011152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JH, Asad S, Chataway TK, Chegini F, Manavis J, Temlett JA, Jensen PH, Blumbergs PC, Gai WP. Peroxiredoxin 6 in human brain: molecular forms, cellular distribution and association with Alzheimer's disease pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115:611–622. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0373-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopacek J, Sakaguchi S, Shigematsu K, Nishida N, Atarashi R, Nakaoke R, Moriuchi R, Niwa M, Katamine S. Upregulation of the genes encoding lysosomal hydrolases, a perforin-like protein, and peroxidases in the brains of mice affected with an experimental prion disease. J Virol. 2000;74:411–417. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.1.411-417.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel C, Sagi D, Kaindl AM, Steireif N, Klare Y, Mao L, Peters H, Wacker MA, Kleene R, Klose J. Comparative proteomics in neurodegenerative and non-neurodegenerative diseases suggest nodal point proteins in regulatory networking. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:1948–1958. doi: 10.1021/pr0601077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SG, Chae HZ, Kim K. Peroxiredoxins: a historical overview and speculative preview of novel mechanisms and emerging concepts in cell signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:1543–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manevich Y, Fisher AB. Peroxiredoxin 6, a 1-Cys peroxiredoxin, functions in antioxidant defense and lung phospholipid metabolism. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:1422–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diedrich JF, Minnigan H, Carp RI, Whitaker JN, Race R, Frey W 2nd, Haase AT. Neuropathological changes in scrapie and Alzheimer's disease are associated with increased expression of apolipoprotein E and cathepsin D in astrocytes. J Virol. 1991;65:4759–4768. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4759-4768.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman DM, Herz J, Bu G. Apolipoprotein e and apolipoprotein e receptors: normal biology and roles in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006312. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barenco MG, Valori CF, Roncoroni C, Loewer J, Montrasio F, Rossi D. Deletion of the amino-terminal domain of the prion protein does not impair prion protein-dependent neuronal differentiation and neuritogenesis. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:806–819. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Jo HY, Kim MH, Cha YY, Choi SW, Shim JH, Kim TJ, Lee KY. H2O2-dependent hyperoxidation of peroxiredoxin 6 (Prdx6) plays a role in cellular toxicity via up-regulation of iPLA2 activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33563–33568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806578200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AB. Peroxiredoxin 6: a bifunctional enzyme with glutathione peroxidase and phospholipase A(2) activities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:831–844. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqui AA, Ong WY, Horrocks LA. Inhibitors of brain phospholipase A2 activity: their neuropharmacological effects and therapeutic importance for the treatment of neurologic disorders. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:591–620. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport SI. In vivo fatty acid incorporation into brain phospholipids in relation to signal transduction and membrane remodeling. Neurochem Res. 1999;24:1403–1415. doi: 10.1023/A:1022584707352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perovic S, Pergande G, Ushijima H, Kelve M, Forrest J, Muller WE. Flupirtine partially prevents neuronal injury induced by prion protein fragment and lead acetate. Neurodegeneration. 1995;4:369–374. doi: 10.1006/neur.1995.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart LR, White AR, Jobling MF, Needham BE, Maher F, Thyer J, Beyreuther K, Masters CL, Collins SJ, Cappai R. Involvement of the 5-lipoxygenase pathway in the neurotoxicity of the prion peptide PrP106-126. J Neurosci Res. 2001;65:565–572. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate C, Williams A. Role of glycosylphosphatidylinositols in the activation of phospholipase A2 and the neurotoxicity of prions. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:3797–3804. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korth C, May BC, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Acridine and phenothiazine derivatives as pharmacotherapeutics for prion disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9836–9841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161274798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull S, Tabner BJ, Brown DR, Allsop D. Quinacrine acts as an antioxidant and reduces the toxicity of the prion peptide PrP106-126. Neuroreport. 2003;14:1743–1745. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200309150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Wagner et al., Cell Communication and Signaling.