Abstract

To establish chronic infections, viruses must develop strategies to evade the host’s immune responses. Many retroviruses, including mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV), are transmitted most efficiently through mucosal surfaces rich in microbiota. We found that MMTV, when ingested by newborn mice, stimulates a state of unresponsiveness toward viral antigens. This process required the intestinal microbiota, as antibiotic-treated mice or germ-free mice did not transmit infectious virus to their offspring. MMTV-bound bacterial lipopolysaccharide triggered Toll-like receptor 4 and subsequent interleukin-6 (IL-6)–dependent induction of the inhibitory cytokine IL-10. Thus, MMTV has evolved to rely on the interaction with the microbiota to induce an immune evasion pathway. Together, these findings reveal the fundamental importance of commensal microbiota in viral infections.

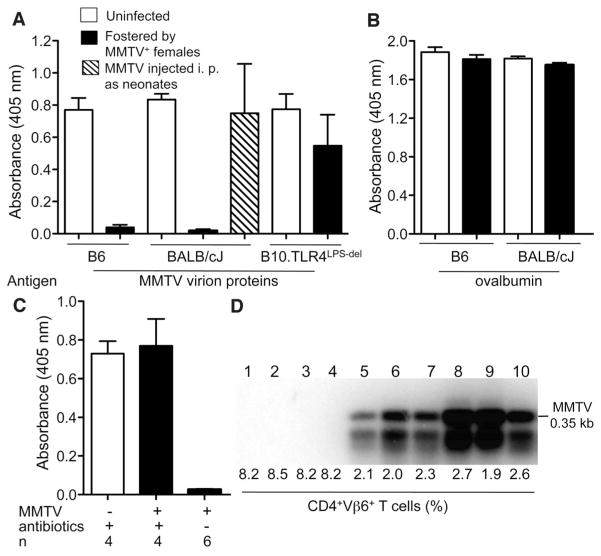

Successful pathogens have developed means to counteract the immune system or even to use established immune mechanisms to their own benefit. Retroviruses, including mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV), are detected by at least one Toll-like receptor (TLR7), and detection is dependent on the adaptor molecule that signals downstream of most TLRs, expressed by myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) (1–3). Retroviruses employ various mechanisms of immune evasion (4, 5), however, and can destroy the immune system (e.g., immunodeficiency viruses of various species) or subvert it (5, 6) to enable successful transmission. Establishment of a state of immunological tolerance to viral proteins in infected animals should also support virus spread. To test whether animals infected with the orally transmitted MMTV were tolerant to MMTVantigens, we immunized them with virion proteins mixed with an adjuvant. Adult animals that have ingested MMTV-laden milk as neonates failed to produce antibodies (Abs) against viral proteins (Fig. 1A), whereas response to a control antigen was intact (Fig. 1B). In contrast, neonates infected through the parenteral route produced virus-specific Abs (Fig. 1A). TLR4-dependent production of the immunoregulatory cytokine interleukin-10 (IL-10) is required for the persistence of MMTV, and deficiency in TLR4 leads to the eventual loss of the original virus (6). MMTV-infected TLR4-deficient C57B10/ScNJ (B10.TLRLps-del) mice that eliminated the virus responded to MMTV proteins after immunization (Fig. 1A). Thus, both the oral route of infection and TLR4 sufficiency were required for induction of immune tolerance to MMTV.

Fig. 1.

Unresponsiveness to MMTV is dependent on the oral route of infection and on microbiota. (A and B) Mice of indicated strains—MMTV-free or infected by fostering on MMTV-infected lactating MMTV(LA) females or infected intraperitoneally (i.p.) at 3 to 5 days of age—were immunized at 8 weeks of age with either MMTV(LA) proteins (A) or ovalbumin (B) in Freund’s complete adjuvant. Production of specific Abs to respective antigens was tested by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Sera from four to eight mice were used per group. One of three experiments is shown. (C) The progeny from the first pregnancy of uninfected and MMTV(LA)-infected B6 females, treated with a mixture of broad-spectrum antibiotics or left untreated, were immunized at 6 weeks of age with MMTV(LA) proteins and tested for virus-specific Abs by ELISA (detailed experimental scheme is shown in fig. S1A). n, number of mice. All graphs, means ± SEM. (D) MMTV infection of mice used in (C) was probed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification (under saturating conditions) of integrated proviruses in splenic DNA followed by Southern blot with an MMTV long terminal repeat (LTR)–specific probe (lanes 1 to 4, offspring of infected antibiotic-treated females; lanes 5 to 10, offspring of infected, untreated females) and by evaluating deletion of SAg-cognate CD4+ Vμ6+ T cells. Uninfected B6 mice (n = 5) had 8.5 ± 0.3% of CD4+Vμ6+ T cells among CD4+ T cells.

TLR4 is a pattern recognition receptor (7) with primary specificity for bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (8). Other ligands have been proposed to activate this receptor (9), however, including MMTV proteins (10). Therefore, MMTV could use either its own proteins or the products of the host intestinal microbiota to trigger TLR4. To discriminate between these possibilities, we used two complementary approaches. First, we treated naturally infected pregnant C57BL/6J (B6) mice with a complex of broad-spectrum antibiotics (fig. S1A). When the first pregnancy offspring were immunized as adults, they responded to MMTV antigens, unlike their antibiotic-free littermates (Fig. 1C). Moreover, these mice were MMTV-free; no integrated proviruses were found in the spleens, and there was no deletion of T cells responsive to viral superantigen (SAg)—both sensitive indicators of MMTV infection (11, 12) (Fig. 1D), even though their mothers continued to produce MMTV into the milk (fig. S1B). Thus, depletion of the commensal microbiota by antibiotics has a profound effect on MMTV replication.

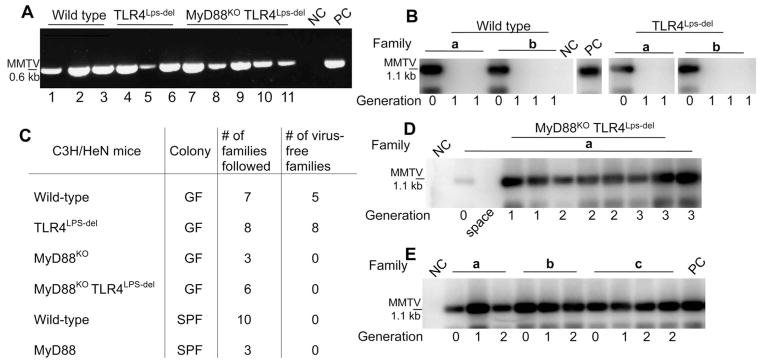

Second, we produced germ-free (GF) C3H/HeN (wild-type) mice, as well as GF C3H/HeN mice deficient in TLR4 (C3H/HeN.TLR4Lps-del), MyD88 (C3H/HeN.MyD88KO), or both TLR4 and MyD88 (C3H/HeN.TLR4Lps-del MyD88KO). GF females of all four strains and control conventional specific pathogen–free (SPF) mice were injected with filter-sterilized MMTV virions isolated from the milk of infected SPF wild-type mice (generation 0, G0) and allowed to breed and to produce progeny (G1). As expected, all G0 females injected with the virus became infected and produced similar amounts of virus into the milk (Fig. 2A and fig. S2A). Whereas all injected SPF mice transmitted infectious virus to their offspring, the majority of wild-type GF mice (five families out of seven tested) failed to pass the virus to their offspring (Fig. 2, B and C, and fig. S2B). It is noteworthy that none of the eight independent C3H/HeN.TLR4Lps-del GF families transmitted infectious MMTV to their young (Fig. 2, B and C). These results supported the importance of microbiota for MMTV transmission and also implicated the TLR4 ligand, LPS, as a key player in this process.

Fig. 2.

Differential MMTV persistence in GF and SPF mice of distinct genotypes. (A) Reverse transcription–PCR detection of MMTV virion RNA in the milk of GF C3H/HeN mice infected parenterally with MMTV(C3H). NC, negative control: RNA from the milk of an uninfected C3H/HeN mouse; PC, positive control: RNA from the milk of an SPF mouse injected with the same viral isolate. MMTV(C3H) and MMTV(LA) were used in two independent studies, data with MMTV(C3H) are shown. To ensure sufficient time for virus amplification in injected mice, the second litters by these dams were used for breeding and testing. (B) Splenic DNA from the first progeny (G1) of i.p. injected mice (G0) was subjected to MMTV-specific PCR, followed by Southern blot hybridization with an MMTV LTR–specific probe. Splenic DNA from an SPF G1 progeny of mice injected with the same virus isolate was used as PC, splenic DNA from an MMTV-negative C3H/HeN mouse was used as NC. a and b, independent families. The figure is assembled from nonconcurrent portions of the same image. (C) Virus fate in the offspring of parenterally infected (G0) mice of different genotypes and maintenance conditions. Summary of data from MMTV-infected mice, showing virus loss or persistence at G1. (D) Transmission of infectious MMTV(C3H) in GF MyD88KOTLR4Lps-del mice. Detection of integrated proviruses was done as in (B). NC, DNA from the spleen of an uninfected C3H/HeN mouse. A single representative family (a) is shown. (E) Transmission of infectious MMTV(C3H) in ASF-associated gnotobiotic wild-type C3H/HeN mice as detected by MMTV(C3H)-specific PCR, followed by Southern blot analysis, performed with splenic DNA of mice from G0 to G2. a to c, different families. Splenic DNA from SPF G1 progeny of mice injected with the same virus isolate served as PC, and splenic DNA from an MMTV-negative C3H/HeN mouse was used as NC. For (A), (B), (D), and (E), PCRs were performed under saturating conditions.

Thus, the incomplete penetrance of the phenotype (loss of MMTV transmission) in the GF wild-type group could result from the presence of LPS in the autoclaved animal feed. The limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) test for LPS established that a GF mouse may consume up to 500 ng of LPS per day (fig. S2C). This consumption is not likely to be uniform, which explains the variation in MMTV loss between different families. In fact, we found LPS in the virus fraction of the milk from one out of five lactating MMTV-infected GF females (fig. S2D).

Infected GF C3H/HeN.MyD88KO and C3H/ HeN.MyD88KOTLR4Lps-del mice transmitted MMTV without exception through multiple generations (Fig. 2, C and D, and fig. S3A), similarly to SPF MyD88KO mice (fig. S3B). This observation makes two critical points. First, it alleviates the concern that the lack of MMTV transmission in GF mice may be due to the underdeveloped gut-associated lymphoid tissues (13) or a paucity of M cells, which are critical for MMTV transmission (14). Second, MMTV transmission by GF MyD88KO mice implies that virus clearance in GF wild-type and TLR4LPS-del animals is MyD88 dependent.

TLR4 signals through either MyD88 or TIR domain–containing adapter inducing interferon-β(TRIF). We found that TRIF was dispensable for virus-elicited IL-10 production, whereas MyD88 was not (fig. S3C). Thus, MyD88 is required for both TLR4- and TLR7-mediated responses to the virus.

Our results suggest that intestinal microbiota are important for successful passage of the virus through the oral route. Furthermore, reconstitution of GF wild-type mice with a defined bacterial community [altered Schaedler’s flora, ASF (15)] restored their ability to transmit the virus (Fig. 2E). The random (from the viral point of view) composition of ASF suggests that immune subversion is not dependent on a particular type of bacteria but requires a bacterially derived ligand, presumably LPS.

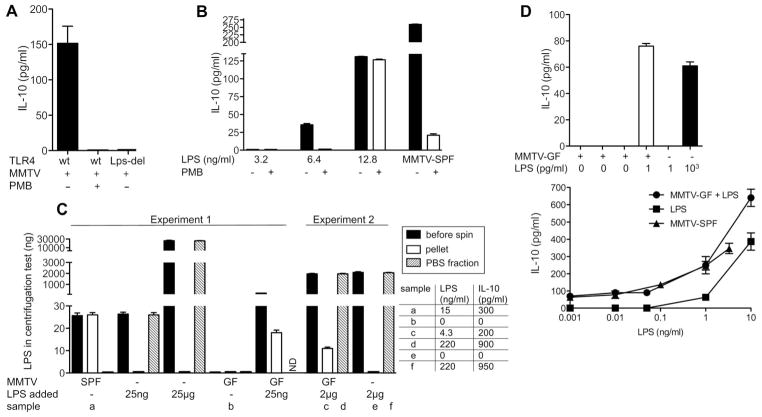

Either LPS could directly bind to MMTVor it could stimulate a milieu of inhibitory cytokines independently of viral infection. An in vitro system was used in which addition of MMTV virions to splenocytes induced production of IL-10 in a TLR4-dependent fashion (6). Polymyxin B (PMB), which binds to and neutralizes LPS activity, alleviated MMTV’s ability to induce IL-10 secretion by wild-type splenocytes (Fig. 3A). PMB was not directly toxic to responding cells, because IL-10 secretion could be restored by addition of an excess of LPS in the presence of PMB (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that MMTV might bind LPS and thereby act as a factor that extracts and concentrates LPS from the environment. In fact, MMTV isolated from mammary glands of lactating females did not contain LPS, whereas MMTV in the stomachs of pups ingesting their milk was laden with LPS (fig. S4A). Gradient centrifugation of MMTV-SPF isolates demonstrated that all LPS in the viral preparation (and its IL-10–eliciting activity) was MMTV-bound (Fig. 3C and fig. S4B). Furthermore, no LPS was pelleted in the absence of the virus, even when 25 μg of LPS (40 μg/ml) was added (1000× the dose of LPS found in virus isolates) during gradient centrifugation (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

MMTV-bound LPS induces production of IL-10. (A) Splenocytes from wild-type C3H/HeN (wt) or C3H/HeN TLR4Lps-del (Lps-del) mice were incubated with an MMTV-SPF isolate in the presence or absence of 0.1 μg/ml PMB. IL-10 was detected in tissue-culture supernatants by ELISA 16 hours later. Graph shows means ± SEM from four independent experiments. (B) Splenocytes from wild-type C3H/HeN mice were incubated with different concentrations of LPS with or without 0.1 μg/ml PMB followed by IL-10 detection as in (A). In parallel, cells were exposed to an MMTV-SPF isolate in the presence or absence of 0.1 μg/ml PMB. Concentration of LPS in the cultures containing the MMTV-SPF isolate was ~13 ng/ml as determined by LAL assay. Graph shows means ± SEM. One of three experiments shown. (C) MMTV-SPF or MMTV-GF virions were ultracentrifuged through 30% sucrose with a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) cushion; the pellet, PBS supernatant (PBS fraction), and initial “before spin” fraction were assayed for LPS by LAL assay. In parallel, indicated amounts of LPS (from Escherichia coli serotype 026:B6) incubated with PBS or MMTV-GF were ultracentrifuged through a sucrose cushion and similarly tested. Several fractions (samples a to f) were tested for the ability to elicit IL-10 in in vitro cultures of C3H/HeN splenocytes (IL-10 and final LPS concentrations in the in vitro cultures are shown in the table). LPS added: total amount of LPS added to MMTV-GF or PBS before centrifugation. ND, not determined. Graph shows means ± SEM. (D) Four independent MMTV-GF isolates (either LPS-free or containing LPS at 1 pg/ml) alone with unbound LPS were compared for their ability to induce IL-10 secretion by splenocytes (left). All virus isolates were normalized by ELISA (not shown). MMTV-SPF at several dilutions, MMTV-GF mixed with various concentrations of LPS, and the same concentrations of free LPS were compared for their ability to induce IL-10 in splenocyte cultures. One of three experiments is shown (right). Graphs show means ± SEM.

MMTV-GF produced by the majority of MyD88KOTLR4Lps-del mice (incapable of restricting viral replication) (Fig. 2D) lacked detectable LPS and failed to elicit IL-10 secretion from wild-type C3H/HeN splenocytes (Fig. 3C and fig. S4C). MMTV-GF isolates contained equal or even greater quantities of the virus compared with the control MMTV-SPF isolates (fig. S4, B and C). Moreover, MMTV-GF was capable of pelleting LPS during gradient centrifugation and then stimulating IL-10 production in in vitro splenocyte cultures (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, binding of LPS by MMTV strongly enhances its ability to induce IL-10 production compared with unbound LPS (Fig. 3, B and D). Note that MMTV-LPS complexes were more sensitive to PMB treatment compared with free LPS (Fig. 3B), which suggests a special type of interaction between MMTV, LPS, and TLR4, or involvement of a highly PMB-sensitive type of LPS. Even the minimal amount of LPS found in a few GF virus isolates was capable of inducing detectable levels of IL-10 in normal splenocytes (Fig. 3D), which supported the conclusion that MMTV propagation in some GF mice (Fig. 2C) was indeed aided by contaminating LPS and the argument that efficient binding of LPS by MMTV is an evolutionary adaptation. We also found that background IL-10 levels in the small intestines of 2-week-old SPF and GF mice were similar and were independent of TLR4 or MMTV infection (fig. S5), which suggested that the background levels of IL-10 in the suckling mice were microbiota-independent. Thus, binding to and concentrating of LPS by MMTV likely occurs in a compartmentalized fashion without affecting the global levels of IL-10 in the gut. Nevertheless, LPS, in addition to stimulating IL-10 production, may also induce proliferation of the virus’ primary targets and thus increase overall viral titers to give the virus an advantage over the immune response.

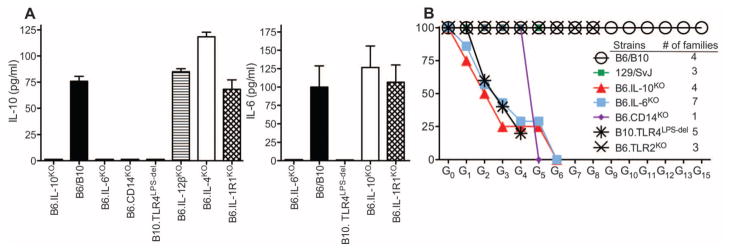

IL-10 is the cytokine likely responsible for the induction of tolerance to MMTV. Whereas TLR4-sufficient myeloid cells were required for IL-10 production by B cells (6), the nature of the IL-10–induced signal produced by myeloid cells was not known. To identify this signal, we tested splenocytes (Fig. 4A) and cells from gut-associated secondary lymphoid organs (fig. S6) from cytokine-deficient mice for their ability to secrete IL-10 upon exposure to the virus in vitro. Whereas IL-4, IL-12, and IL-1 were dispensable for induction of IL-10, IL-6 was found to be critical (Fig. 4A). Secretion of IL-6 was dependent on TLR4, but not IL-10, which places TLR4 upstream of IL-6, and IL-6 upstream of IL-10. B6.CD14KO splenocytes also failed to produce IL-10 when exposed to MMTV (Fig. 4A), which suggests that CD14 (a co-receptor for TLR4 binding of LPS) also participates in the MMTV-mediated LPS interaction with TLR4.

Fig. 4.

Genetic delineation of the immune subversion pathway induced by MMTV-LPS triggering of TLR4. (A) Splenocytes from B6 or B10 wild-type (used interchangeably), or from indicated knockout or mutant mice were incubated with an MMTV-SPF isolate followed by detection of IL-6 and IL-10 in supernatants by ELISA. Three to five mice were used per group. Graphs show means ± SEM. (B) Virus elimination in subsequent generations of mice with deficiencies within the immune sub-version pathway. G0 mice were fostered by SPF MMTV(LA)-infected C3H/HeN females. At least three animals per family were analyzed for hallmarks of infection: deletion of SAg-cognate T cells, viral RNA in the milk (table S1 and fig. S8A), and integrated proviruses in spleens (fig. S8B). A family that eliminated the virus was allowed to produce the next generation of mice, which was also tested to confirm virus loss. MMTV(LA)-infected B6 and B10 mice were used as controls. To control for background modifiers, 129/SvJ mice were also included, as many targeted knockout mice were originally generated on the 129/SvJ background.

To confirm by a genetic approach that the proposed chain of events (MMTV+LPS → TLR4 → IL-6 → IL-10) is involved in the MMTV subversion pathway in vivo, we utilized B6.IL-6KO, B6.IL-10KO, B6.CD14KO, B10. TLR4Lps-del, and B6.TLR2KO mice. MMTV fate was followed through multiple generations in infected mouse pedigrees. Both IL-6– and IL-10–deficient animals eliminated MMTV in successive generations, as did B10.TLR4Lps-del and CD14KO, but not TLR2KO, mice (Fig. 4B and table S1). Thus, our results support a model (fig. S7) whereby LPS-induced signaling drives a viral “subversion” pathway via IL-10 production that promotes viral transmission to successive generations.

Detailed analysis of the actual viral load in subsequent generations of infected IL-10KO and IL-6KO mice revealed that it was reduced gradually and that it took different numbers of passages for various families to completely eliminate the virus (table S1 and fig. S8). Thus, it appears that, in early generations, a high viral load can compensate for the loss of the TLR4-dependent subversion pathway and overpower the adaptive immune response. However, the virus is eventually lost in each infected mouse pedigree, as the virus load is reduced with each subsequent passage (fig. S8).

Commensal microbiota are required for many homeostatic functions of the intestinal mucosa and other barrier tissues. Microbiota control tissue repair (16), induction of tolerance to self [including tolerance to itself (17) and to auto-antigens of the host (18)], and oral tolerance of adults to ingested antigens (19, 20). At present, it is unknown whether neonatal oral tolerance is also dependent on microbiota or whether MMTV induces neonatal oral tolerance to itself by a unique mechanism available to retroviruses. Commensals interact with various pathogens and protect the host against infection with pathogenic and opportunistic bacteria (21), protozoa (22), and fungi (23) or facilitate infection with helminthes (24). However, the role of commensal bacteria in viral transmission and/or pathogenesis is only beginning to unravel. It is highly likely that bacterial microbiota can play both protective (25) and abetting roles (present report) in their interactions with viruses. The lack of knowledge in this area makes it important to expand such investigations to other systems. It is not yet clear whether other viruses take advantage of bacterial products, such as LPS, to achieve successful transmission. Retroviruses transmitted through mucosal surfaces may also use similar strategies. In humans, the highest risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission occurs across mucosal surfaces among individuals who practice receptive anal intercourse (26), and risk is also high in infants breastfed by HIV-infected mothers (27, 28). This study sheds light on the previously unknown role of commensal microbiota in retroviral pathogenesis and suggests new approaches to the prevention of mucosal transmission, viral-specific vaccination, and therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Theriault and A. Vest for their help in monitoring gnotobiotic animals. This work was supported by T32GM007183 to M.K., K.K., and C.M.; by T32 AI065382-01 to L.C.; by Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation grants 2005-204 and 2007-353; by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) NIH AI082418 and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH, Digestive Disease Research Core Center grant DK42086 to A.V.C.; by National Cancer Institute, NIH, grant CA100383 and NIAID grant AI090084 to T.V.G.; and by a grant (P30 CA014599) to The University of Chicago. A material transfer agreement is required for use of the SPF and GF C3H-based mutant strains of mice. The data reported in this paper are tabulated in the main paper and the supporting online material.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/334/6053/245/DC1

Materials and Methods

References (29–48)

References and Notes

- 1.Browne EP, Littman DR. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000298. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy AW, Graham DR, Shearer GM, Herbeuval JP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:17453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707244104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kane M, et al. Immunity. 2011;35:135. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malim MH, Emerman M. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:388. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dittmer U, et al. Immunity. 2004;20:293. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jude BA, et al. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:573. doi: 10.1038/ni926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Janeway CA., Jr Nature. 1997;388:394. doi: 10.1038/41131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poltorak A, et al. Science. 1998;282:2085. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawai T, Akira S. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rassa JC, Meyers JL, Zhang Y, Kudaravalli R, Ross SR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042355399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golovkina TV, Dudley JP, Ross SR. J Immunol. 1998;161:2375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marrack P, Kushnir E, Kappler J. Nature. 1991;349:524. doi: 10.1038/349524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill DA, Artis D. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:623. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golovkina TV, Shlomchik M, Hannum L, Chervonsky A. Science. 1999;286:1965. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dewhirst FE, et al. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3287. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.8.3287-3292.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Cell. 2004;118:229. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Medzhitov R. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1(Suppl 1):S10. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wen L, et al. Nature. 2008;455:1109. doi: 10.1038/nature07336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreau MC, Corthier G. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2766. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.10.2766-2768.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sudo N, et al. J Immunol. 1997;159:1739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stecher B, Hardt WD. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:107. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benson A, Pifer R, Behrendt CL, Hooper LV, Yarovinsky F. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:187. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wargo MJ, Hogan DA. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:359. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayes KS, et al. Science. 2010;328:1391. doi: 10.1126/science.1187703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ichinohe T, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019378108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Royce RA, Seña A, Cates W, Jr, Cohen MS. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1072. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nduati R, et al. JAMA. 2000;283:1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.9.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Humphrey JH, et al. ZVITAMBO study group. BMJ. 2010;341:c6580. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c6580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.