Abstract

CLL remains incurable with chemoimmunotherapy, and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) offers potential for cure. We assessed the outcomes of 108 CLL patients undergoing first allogeneic HSCTs, 76 with reduced intensity (RIC) and 32 with myeloablative (MAC) conditioning between 1998 and 2009 at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. With median follow-up 5.9 years in surviving patients, the 5 year OS for the entire cohort is 63% for RIC regimens and 49% for MAC regimens (p=0.18). The risk of death declined significantly starting in 2004 and we found that 5 year OS for HSCT between 2004–2009 was 83% for RIC regimens compared to 47% for MAC regimens (p=0.003). For RIC transplantation, we developed a prognostic model based on predictors of PFS, specifically remission status, LDH, comorbidity score and lymphocyte count, and found 5-year PFS 83% for score 0, 63% for score 1, 24% for score 2, and 6% for score >= 3 (p<0.0001). We conclude that RIC HSCT for CLL in the current era is associated with excellent long-term PFS and OS, and, as potentially curative therapy, should be considered early in the disease course of relapsed high-risk CLL patients.

Keywords: CLL, RIC, myeloablative, SCT, prognostic model

INTRODUCTION

Despite recent therapeutic advances that include highly effective chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) regimens(1–3) and alemtuzumab(4), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) remains an incurable disease with standard therapy, with reported overall survival after third-line chemotherapy ranging from 34–47 months(5, 6). Although autologous transplantation (ASCT) initially appeared promising, long-term follow-up of CLL patients treated with ASCT has revealed that relapse is ongoing, suggesting that ASCT is unlikely to be curative(7–9). Furthermore, recent randomized trials of autologous SCT have shown improved EFS without impact on OS(10, 11), and the EFS observed with ASCT in these studies is similar to that seen with FCR CIT(12, 13).

Early studies of myeloablative allogeneic transplantation (MAC) established that long-term remissions are possible(14–16), albeit with a high NRM, ranging from 10% to 40% even in relatively young patients(8, 15–21). Interest therefore turned toward RIC approaches in an effort to reduce NRM(22–25), which is now generally in the 15–30% range at 3–5 year follow-up(24–27). Recent data also suggest that RIC HSCT can induce long-term disease free survival even in very high-risk CLL with deletion 17p(24, 26).

However, particularly for patients with refractory or bulky disease at transplant, relapse remains a significant problem, with cumulative incidence as high as 36–40% at 4–5 year follow-up(24–27), and in our own DFCI series of refractory patients, 48% at two years(28). Since outcomes of transplantation have improved over the last decade, we were interested in reassessing the outcomes of these patients, and in particular looking at whether dose intensity in CLL patients eligible for myeloablative HSCT might have benefit in a more modern era. A retrospective comparison of RIC HSCT patients to matched patients who received MAC found that, as expected, NRM was reduced in the RIC HSCT patients, but this benefit was offset by an increased relapse rate, leading to equivalent event-free and overall survival(29). We have evaluated the outcomes of all CLL patients who underwent HSCT at DFCI from 1998 to 2009. Although over this period the patients who had RIC HSCT differed systematically from those who underwent MAC HSCT, we found that since 2004, the patient groups were well-matched and patients undergoing RIC HSCT benefited from reduced NRM and reduced relapse, leading to significantly better overall survival not seen with MAC HSCT. Furthermore, we developed a prognostic model for outcome which correlates well with PFS, OS and relapse in our cohort. The improved outcomes of RIC HSCT and the utility of our prognostic model for patient selection further support the earlier consideration of HSCT in these patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Population

One hundred and eight consecutive patients with a diagnosis of CLL who underwent first allogeneic HSCT from a HLA-matched adult donor (6/6) from 1998 to 2009 at DFCI were included in the initial analysis. The RIC-specific analysis then focused on 76 patients who underwent allogeneic HSCT between January 2001 and December 2009. Eligibility criteria for allogeneic HSCT for CLL typically included disease refractory to purine analogues or similar intensity therapy, disease showing progressively less benefit from purine analogues as demonstrated by a remission duration less than 12–24 months, failure to respond to salvage therapy, or the presence of 17p deletion. Patients were treated prospectively on treatment plans or research protocols that were approved by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to therapy. Transplantation eligibility requirements included ECOG performance status 0–2, left ventricular ejection fraction >30%, and no uncontrolled infection. The choice of RIC or MAC was at the discretion of the treating physician in consultation with the patient and was primarily dependent on the age and general health of the patient as well as the perceived refractoriness of the disease. MAC regimens consisted primarily of cyclophosphamide and total body irradiation (14 Gy in 7 fractions). RIC regimens consisted of fludarabine 30 mg/m2 and intravenous busulfan 0.8 mg/kg, both given for 4 days. Seven patients eligible to be included in the RIC cohort were enrolled on a clinical trial of vaccination with killed autologous tumor after HSCT and were excluded from the analyses. Comorbidity scores were determined by retrospective chart review(30).

Donors

All donors included in this analysis were HLA matched at A, B, and DR loci. Between 1998 and 2000, class I typing was low resolution, with high resolution class II typing for unrelated donors. Between 2001 and 2004, allele level typing was added for HLA-A and HLA-B, with high resolution class II typing. From 2005 to the present, high resolution molecular typing has been used for HLA class I and II for all donors. HLA C mismatches were present in 9 of the 90 patients tested; patients undergoing HSCT early in this time period were not uniformly assessed for HLA C status. PBSC donors were mobilized with filgrastim at 10 mcg/kg/day for 5 days. Stem cell collection began on day 5 of filgrastim and was targeted to collect >5 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg. Donor bone marrow was collected in the operating room under anesthesia and the targeted cell dose was >2 × 108 nucleated cells/kg.

GVHD Prophylaxis

All patients received immunosuppressive therapy for GVHD prophylaxis on consecutive protocols. The distribution of regimens is detailed in Table 1. No anti-thymocyte globulin or alemtuzumab was used as part of HSCT conditioning, but 9 MAC patients did receive grafts that underwent ex vivo T cell depletion. No planned or preemptive donor lymphocyte infusions (DLIs) were given after RIC HSCT. Immunosuppressive medications were tapered as clinically permitted over 3–12 months following HSCT. All patients received prophylaxis for Pneumocystis jurivecii pneumonia and Herpes/Varicella virus reactivation. Patients were monitored for peripheral blood CMV reactivation by DNA hybrid capture or quantitative PCR assays during the first 100 days post transplant, and pre-emptive therapy with ganciclovir or valganciclovir was started if CMV reactivation was detected. Acute and chronic GVHD was graded according to consensus criteria(31, 32).

Table 1.

Patient and Transplant Characteristics

| 1998–2009 | 2004–2009 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| MAC | RIC | P | MAC | RIC | P | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| N | 32 | 76 | 14 | 42 | ||

| Age (yrs) | ||||||

| <50 | 21 (66) | 22 (29) | 0.001 | 8 (57) | 9 (21) | 0.03 |

| 50 – <65 | 11 (34) | 48 (63) | 6 (43) | 29 (69) | ||

| ≥65 | 6 (8) | 4 (10) | ||||

| median (range) | 48 (27, 60) | 55 (36, 73) | 0.0001 | 47 (30, 58) | 57 (42, 73) | 0.0003 |

| Sex, Female | 10 (31) | 19 (25) | 0.63 | 3 (21) | 10 (24) | 1 |

| Pt-Donor Sex Match, M-F | 13 (41) | 25 (33) | 0.51 | 7 (50) | 17 (40) | 0.55 |

| Cell Source | ||||||

| PBSC | 18 (56) | 75 (99) | <0.001 | 14 (100) | 42 (100) | ---- |

| Donor Type | ||||||

| MUD | 13 (41) | 48 (63) | 0.04 | 9 (64) | 24 (57) | 0.76 |

| Disease Status | ||||||

| CR | 1 (3) | 6 (8) | 0.83 | 1 (7) | 4 (10) | 0.78 |

| nPR | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | ||||

| PR | 18 (56) | 36 (47) | 6 (43) | 26 (62) | ||

| SD | 5 (16) | 17 (22) | 3 (21) | 7 (17) | ||

| PD | 8 (25) | 16 (21) | 4 (29) | 5 (12) | ||

| No Prior Regimens | ||||||

| 1–3 | 17 (53) | 27 (36) | 0.13 | 6 (43) | 18 (43) | 1 |

| 4–9 | 15 (47) | 49 (64) | 8 (57) | 24 (57) | ||

| median (range) | 3 (1, 8) | 4 (1, 9) | 0.11 | 5 (1, 8) | 4 (1,9) | 0.76 |

| Purine Analogue Refractory | ||||||

| Yes | 22 (69) | 42 (55) | 0.13 | 12 (86) | 20 (48) | 0.02 |

| No | 10 (31) | 31 (41) | 2 (14) | 20 (48) | ||

| Not given | 0 (0) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | ||

| GVHD Prophylaxis | ||||||

| Sirolimus Containing | 12 (38) | 52 (68) | 0.005 | 11 (79) | 41 (98) | 0.04 |

| GVHD Prophylaxis | ||||||

| Sirolimus/Tacrolimus +MTX | 12 (38) | 50 (64) | ---- | 11 (79) | 39 (93) | |

| Sirolimus/MMF | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 2 (5) | |||

| Tacrolimus ± MTX | 6 (19) | 7 (9) | 3 (21) | 1 (2) | ||

| CSA + Other | 5 (16) | 16 (21) | ||||

| T Cell Depletion | 9 (28) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Year of transplant, >=2004 | 14 (44) | 42 (55) | 0.3 | |||

MAC: Myeloablative Conditioning; RIC: Reduced Intensity Conditioning

Cytogenetic Analysis

Standard metaphase karyotype analysis was performed on bone marrow aspirates or peripheral blood, together with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for the most common CLL abnormalities, as previously described(33). If FISH analysis was not performed on a sample with active disease, patients were considered unevaluable for cytogenetic abnormalities. Cytogenetic data were available for 12 patients undergoing MAC HSCT and 51 patients undergoing RIC HSCT. The analyses of cytogenetics and outcome were therefore confined to the patients undergoing RIC HSCT. Please see Supplementary Methods for further details of this analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. OS was defined as the time from stem cell infusion to death from any cause; those alive or lost to follow-up were censored at the date last known alive. PFS was defined as the time from stem cell infusion to disease relapse, progression or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. Complete and partial remission and progressive disease were defined according to the National Cancer Institute Working Group (NCI-WG) criteria for CLL used at the time these transplantations were performed(34), supplemented with CT scan evaluation and surveillance bone marrow biopsies with flow cytometry. Patients who were alive without disease relapse or progression were censored at the time last seen alive and disease-free. Please see Supplementary Methods for additional details on the statistical approach.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Outcomes for MAC and RIC Transplantations

The characteristics of this patient population are detailed in Table 1. In the entire study period, the patient populations for MAC and RIC transplantations differed systematically with respect to age, stem cell source, related vs. unrelated donor and use of sirolimus-containing GVHD prophylaxis. For the entire population, PFS and OS were not significantly different between the two conditioning groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Survival and GVHD Outcomes

| 1998–2009 | 2004–2009 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Outcome | MAC | RIC | p-value | MAC | RIC | p-value |

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |||

| N | 32 | 76 | 14 | 42 | ||

| Median Follow-up (years) | 8.1 (1.0, 13.0) | 5.1 (1.8, 10.1) | 0.02 | 4.6 (1.0, 7.1) | 4.7 (1.8, 6.9) | 0.89 |

| Median Follow-up (years) | 5.9 (1.0, 13.0) | 4.7 (1.0, 7.1) | ||||

| 5-year OS | 49 (31, 65) | 63 (51, 73) | 0.18 | 47 (19, 71) | 83 (67, 91) | 0.003 |

| 5-year PFS | 36 (19, 52) | 43 (31, 55) | 0.23 | 47 (19, 71) | 64 (46, 78) | 0.15 |

| Cumulative Incidence | ||||||

| 5-year NRM | 48 (29, 64) | 16 (9, 26) | 0.0004 | 46 (17, 71) | 9.5 (3, 21) | 0.001 |

| 5-year Relapse | 17 (6, 33) | 40 (27, 52) | 0.02 | 7 (0.4, 29) | 26 (13, 42) | 0.13 |

| Max Cum Inc gr. II–IV aGVHD | 50 (31, 66) | 30 (20, 41) | 0.01 | 57 (27, 79) | 31 (18, 45) | 0.02 |

| Cum Inc cGVHD, 2-year | 51 (31, 68) | 65 (53, 75) | 0.12 | 68 (29, 89) | 63 (46, 75) | 0.93 |

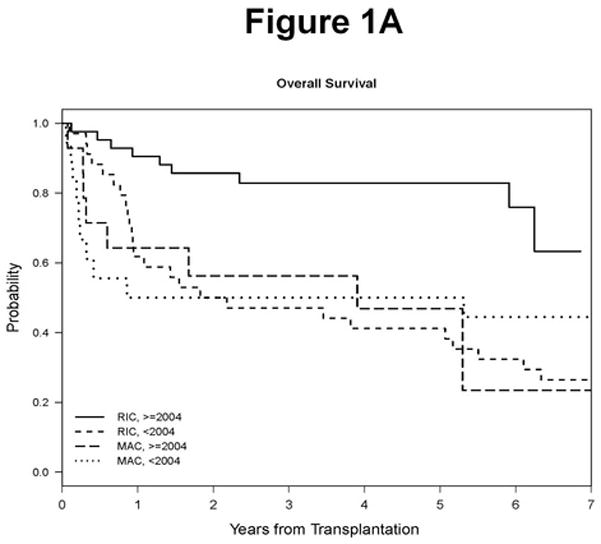

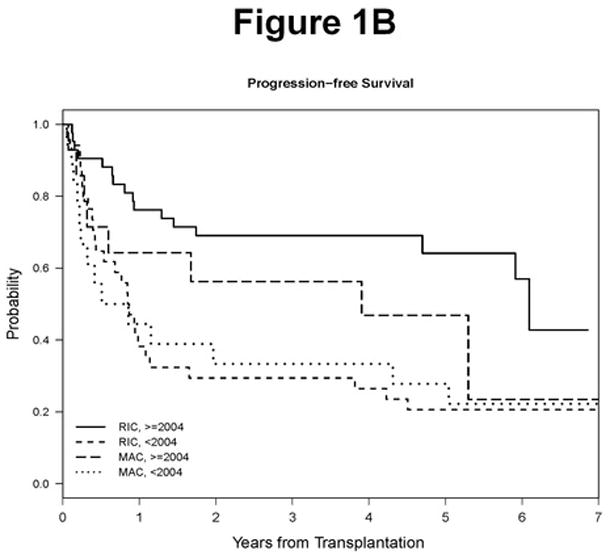

However, we noted that the risk of death in relation to year of transplantation declined significantly beginning in 2004, suggesting that a significant OS difference would be evident between HSCTs performed prior to 2004 compared to after (Supplementary Figure 1). We therefore looked at HSCTs performed between 2004 and 2009. First, we noted that the MAC and RIC patient populations were more comparable, with the only significant differences being age (median age 47 vs 57, respectively, p=0.0001; Table 1) and the percentage of patients who were purine analogue refractory (86% for MAC vs 48% for RIC, p=0.02, Table 1). A significant OS advantage favoring RIC HSCT did emerge for this later period (5-year OS: 83% in RIC and 47% in MAC, p=0.003; Table 3, Figure 1A), with a suggestion of a difference in PFS which did not reach statistical significance (64% in RIC and 47% in MAC, p=0.15; Table 3, Figure 1B). As shown in Table 3, this difference in OS and PFS for RIC HSCT was primarily due to lower NRM compared to MAC HSCT and improved relapse rate compared to earlier time periods of RIC (5 year cumulative incidence of NRM 46% for MAC vs 9.5% for RIC, p=0.001; 5 year cumulative incidence of relapse 7% for MAC vs 26% for RIC, p=0.13). In addition, the rate of grade II–IV acute GVHD was significantly lower with RIC compared to MAC (31% vs 57%, respectively, p=0.02). These outcomes justify the current focus on RIC HSCT in CLL, and we will therefore focus the remainder of our discussion on that patient population.

Figure 1. Survival Outcomes.

A. Overall survival by conditioning regimen type and year. B. Progression free survival by conditioning regimen type and year.

RIC Patient Characteristics

Additional details of the 76 patients who underwent RIC HSCT between 2001 and 2009 are provided in Table 2. The median number of prior regimens was 4, and 43% were transplanted with stable or progressive disease (Table 1). 30% of patients had an elevated LDH and 21% had bulky disease at the time of transplantation. 30% had known high risk cytogenetics (complex, del17p, or del11q), with an additional 33% lacking cytogenetic data. 62% of patients had a comorbidity score of zero, but retrospective determination may have underestimated the true comorbidity in some patients.

Table 2.

RIC Patient Baseline Characteristics (N=76)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Prior Autologous HSCT | 10 (13) |

| Cytogenetics | |

| High Risk* | 23 (30) |

| Standard Risk | 28 (37) |

| Unavailable | 25 (33) |

| del (17p) | |

| Yes | 13 (17) |

| No | 38 (50) |

| Unavailable | 25 (33) |

| del(11q) | |

| Yes | 6 (8) |

| No | 45 (59) |

| Unavailable | 25 (33) |

| Lymphocytes, median (range) | 800 (30 – 116,700) |

| BM involvement**, median (range) | 6 (0 – 100) |

| Comorbidity score | |

| 0 | 47 (62) |

| 1 | 10 (13) |

| 2 | 6 (8) |

| 3 | 9 (12) |

| 4 | 3 (4) |

| 6 | 1 (1) |

| High LDH | 23 (30) |

| Bulk >=5 cm | 16 (21) |

| Time of Transplant | January 2001 – December 2009 |

Del 11q, del 17p, complex (≥ 3 abnormalities)

10 patients have missing information

RIC Progression-Free and Overall Survival

With a median follow-up of 5.1 years in survivors, the 5 year OS was 63% (95% CI 51–73%), and the 5 year PFS was 43% (31–55%) (Table 3, Figures 1A, B). For the period since 2004, with a median follow-up of 4.7 years, the 5 year OS was 83%. We were interested in exploring predictors of outcome in these RIC HSCT patients. In evaluating age, we observed that worse outcomes were seen at both lower and higher ages, with the lowest risk at about age 55 (higher risk < 50, >=65; Supplementary Figure 2). This is likely because in the time period when many of these transplantations were done, the patients under age 50 who underwent RIC HSCT had specific contraindications to MAC HSCT, including prior HSCT (n=6), comorbidities (n=6) or very poor disease status (n=10). For the purposes of further analysis we therefore dichotomized age as between 50 and 64 inclusive, or outside that range. This variable defined a 5 year OS of 74% for those aged 50–64, as compared to 44% for those outside that range (p=0.002, Supplementary Figure 3).

In univariable analysis assessing predictors of OS, age (HR 0.35 for age 50–<65 vs age>=65 or age<50, p=0.003), disease status at conditioning (HR 2.67 for SD/PD vs CR/PR, p=0.005), sirolimus use (HR 0.28, p=0.0003), bulk (HR 2.21 for >5cm vs <=5cm, p=0.01), LDH (HR 2.21 for high vs low, p=0.02), comorbidity score (HR 2.0 for >=1 vs 0, p=0.04), bone marrow involvement (continuous HR 1.01, p=0.005), and year of HSCT (HR 0.26 for >=2004 vs <2004, p=0.0005) were significantly associated with OS (Supplementary Table 1). In univariable analysis assessing predictors of PFS, the same factors were significant, with the addition of lymphocyte count at transplant conditioning, which was also significantly associated with PFS (HR 1.31 for log transformed lymphocyte count, p=0.002; Supplementary Table 1).

To reduce the number of predictors in Cox models, penalized multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were constructed to evaluate the impact of pretransplantation variables on PFS and OS. Significant variables predicting OS were age (HR 0.35 for 50–<65, p=0.007), sirolimus containing GVHD prophylaxis (HR 0.29, p=0.0005), bulk > 5 cm (HR 4.17, p = 0.003), bone marrow involvement as a continuous variable (HR 1.01, p=0.03), and year of transplantation (HR 0.37 for ≥2004 compared with <2004, p=0.01) (Table 4). Disease status was not selected due largely to its collinearity with bulky disease. Significant variables predicting PFS were age (HR 0.38 for 50–64, p=0.005), SD/PD compared to CR/PR (HR 2.32, p=0.02), bone marrow involvement as a continuous variable (HR 1.01, p=0.023), log-transformed lymphocyte count (HR 1.33, p=0.006), high LDH (HR 2.50, p=0.01) and comorbidity score >=1 (HR 2.09, p=0.025; Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariable Cox Model for the Entire RIC Cohort (n=76)

| OS | PFS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | ||||

| 50<=Age<65 vs Age<50 or Age>=65 | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.75 | 0.007 | 50<=Age<65 vs Age<50 or Age>=65 | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.75 | 0.005 |

| BM Involvement: Continuous | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.03 | 0.03 | SD/PD vs CR/PR | 2.32 | 1.14 | 4.70 | 0.02 |

| Bulk: >5cm vs <=5 cm | 4.17 | 1.65 | 10.53 | 0.003 | Comorbidity Score: >=1 vs 0 | 2.09 | 1.10 | 3.98 | 0.025 |

| 1 Sirolimus Containing Prophylaxis vs Others | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.58 | 0.0005 | 2 BM Involvement: Continuous | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 0.023 |

| 1 Year of HSCT: >=2004 vs <2004 | 0.37 | 0.16 | 0.82 | 0.015 | LDH: High vs Normal | 2.50 | 1.22 | 5.13 | 0.01 |

| 2 Log (Lymphocyte Count) | 1.33 | 1.09 | 1.64 | 0.006 | |||||

Separate models were fit for these variables due to collinearity

RIC Non-Relapse Mortality and Relapse

Infection, GVHD and respiratory failure were the most common causes of NRM. Non-relapse death accounted for 19 out of 35 deaths after RIC HSCT, compared to all 18 deaths after MAC HSCT. The 5 year cumulative incidence of NRM in RIC HSCT was 16% for the entire study period, and 9.5% for the 2004–2009 period (Table 3), showing improvement over this period (Supplementary Figure 4A).

Relapse with or without death occurred in 30 patients in the RIC group. The 5 year cumulative incidence of relapse in RIC HSCT was 40% for the entire study period and 26% for the period 2004–2009, again showing improvement (Supplementary Figure 4B). Univariable competing risks models were performed to assess the impact of pretransplantation variables on relapse and on NRM. Significant predictors of relapse included SD/PD at conditioning (HR 3.82, p=0.0004), an elevated LDH at HSCT (HR 3.3, p=0.001), the log-transformed lymphocyte count (HR 1.33, p=0.001), age (HR 0.487 for 50–64, p=0.049), and year of HSCT >= 2004 (HR 0.401, p=0.016) (Table 5). No significant predictors of NRM were identified (data not shown).

Table 5.

Univariable Competing Risks Model for Relapse: RIC Cohort (n=76)

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50<=Age<65 vs Age<50 or Age>=65 | 0.487 | 0.28 | 1 | 0.049 |

| SD/PD vs CR/PR | 3.82 | 1.83 | 7.98 | 0.0004 |

| BM Involvement: Continuous | 1.01 | 1 | 1.02 | 0.057 |

| Log (Lymphocyte Count) | 1.33 | 1.12 | 1.58 | 0.001 |

| LDH: High vs Normal | 3.3 | 1.61 | 6.76 | 0.001 |

| Year of HSCT: >=2004 vs <2004 | 0.401 | 0.191 | 0.841 | 0.016 |

RIC Graft vs. Host Disease

A lower incidence of grade 2–4 acute GVHD was observed for RIC HSCT compared to MAC for the entire period (50% for MAC vs 30% for RIC, p=0.01), as well as since 2004 (57% for MAC vs 31% for RIC, p=0.02). However, in the RIC HSCT group, neither the cumulative incidence of grade 2–4 acute GVHD nor the incidence of chronic GVHD differed between the entire study period and the period since 2004 (30% vs 31%, respectively, for aGVHD; 62% vs 63%, respectively, for cGVHD) (Table 3). In a landmark analysis that excluded early deaths and relapses prior to day 100, patients without cGVHD showed a higher cumulative relapse rate compared to those with cGVHD (5 year cumulative relapse rate: 53% vs 19%, p<0.001) but no significant difference was observed in NRM (11% vs 17%, respectively, p=0.46). The cumulative incidence of acute and chronic GVHD are shown for RIC HSCT in Supplementary Figures 5A and 5B.

RIC: Hematopoietic Donor Chimerism

Of the 76 patients, 72 patients had day 30 post HSCT donor chimerism data available. The median donor chimerism achieved on day +30 was 92% (range 0, 100); and 74% (53/72) achieved ≥75% donor chimerism by day 30. The 5 year OS for patients with donor chimerism ≥75% at day +30 was 68% (95% CI: 54%, 79%) compared to 53% (95% CI: 29%, 72%) for those with <75% donor chimerism (p=0.03). The 5 year PFS for patients with donor chimerism ≥75% at day +30 was 53% (95% CI: 37%, 66%) compared to 16% (95% CI: 4%, 35%) for those with <75% donor chimerism (p=0.0002). The 5 year cumulative incidence of relapse for patients with donor chimerism ≥75% at day +30 was 32% (95% CI: 19%, 46%) compared to 74% (95% CI: 46%, 89%) for those with <75% donor chimerism (p=0.0006). In univariable logistic regression analysis, disease status (CR/PR OR=4.59, p=0.008), lower bone marrow involvement (OR 1.03, p=0.003), lower log lymphocyte count (OR 5.41, p=0.0002), and bulk<=5cm (OR 5.70 p=0.006) were predictors of day 30 chimerism>=75%.

RIC Cytogenetics

In univariable analysis looking at 5 year PFS and OS for 17p deletion vs not, and 11q deletion vs not, no difference in OS or PFS was observed in either group (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Figure 6A). Although the degree to which 11q deletion and complex abnormalities are high risk remain controversial in CLL, we did consider the effect of any high risk cytogenetics, defined here as 17p, 11q, or complex (Supplementary Table 2; Supplementary Figure 6B). The 5 year OS was 60% for patients with high risk cytogenetics and 71% for patients with standard risk cytogenetics (p=0.68), and the 5 year PFS was 43% and 51%, respectively (p=0.33) (Supplementary Table 2). In our previous analysis with shorter follow-up, high-risk cytogenetics was a significant adverse predictor of PFS in univariable analysis(28), but this is no longer the case with prolonged follow-up, in which some patients with high-risk cytogenetics demonstrate extended survival.

A recent report suggested that complex cytogenetics alone are an adverse prognostic factor for CLL after HSCT(35). Only 10 RIC patients in our cohort were known to have complex cytogenetics, and they showed a 5 year OS of 40% compared to 72% for all others (p=0.15) and a 5 year PFS of 40% compared to 49% for all others (p=0.75). Although this 5 year OS difference appeared large, we found that 4 of 10 patients with complex cytogenetics are still alive with follow up time ranging from 4 to 9 years, and thus OS curves equalized after 5 years (Supplementary Figure 6C).

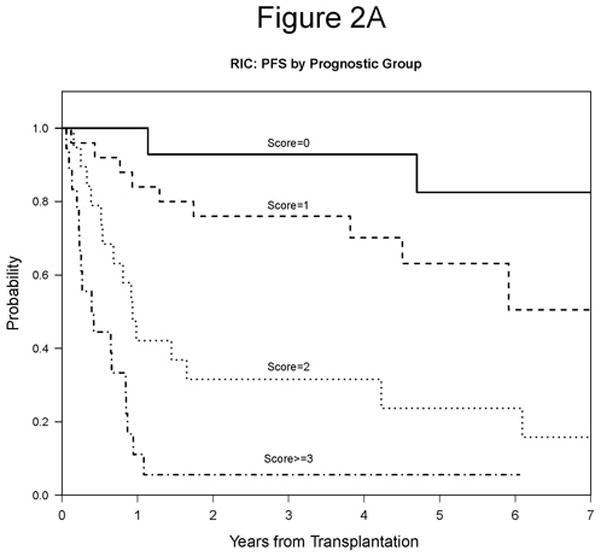

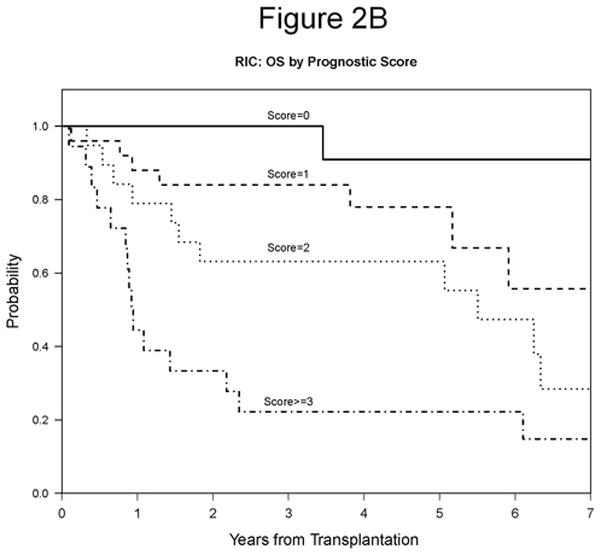

RIC: Prognostic Model for PFS

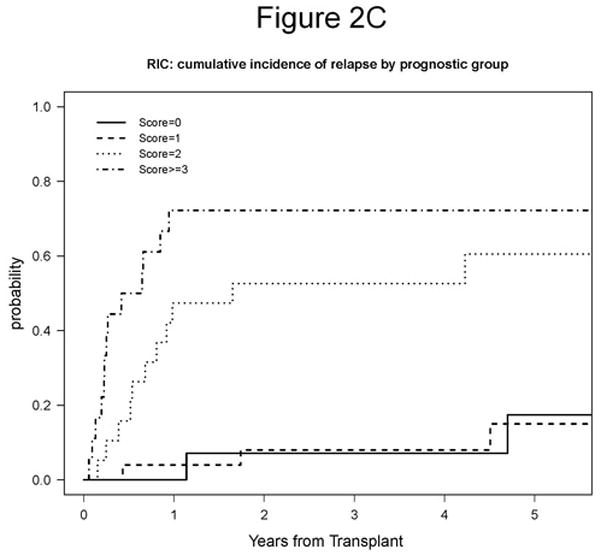

We were interested in developing a model that would be prognostic of RIC HSCT outcome in the current era. We chose to focus on predictors of PFS identified here because PFS has the most events and is unaffected by choice of salvage therapy. Four variables were considered in building the prognostic score: disease status at conditioning (SD/PD vs CR/PR), LDH (high vs normal), comorbidity (>=1 vs 0), and lymphocyte count (>1000/μL vs <=1000/μL). Age was not considered since it is not CLL specific, and bone marrow involvement was not considered due to missing data. One point was assigned for each adverse variable, namely SD/PD, high LDH, one or more comorbidities, or lymphocyte count >1,000/μL. Variable specific scores were then summed and risk group was assigned based on the overall score. Using this grouping, our model successfully stratified patients by 5-year PFS, which was 83% for Score 0, 63% for Score 1, 24% for Score 2, and 6% for Score >= 3 (p<0.0001; Table 6, Figure 2A). We then evaluated the association between our prognostic model score and OS and relapse. The 5-year OS was 91% for Score 0, 78% for Score 1, 63% for Score 2, and 22% for Score >= 3 (p<0.0001; Table 6, Figure 2B). The 5-year cumulative incidence of relapse was 17% for Score 0, 15% for Score 1, 61% for Score 2, and 72% for Score >= 3 (p=0.00002; Table 6, Figure 2C). We conclude that this prognostic score is highly associated with outcome in our cohort and should therefore be validated in other CLL HSCT cohorts.

Table 6.

RIC: Clinical Outcomes by Risk Score

| Risk Score | N | 5-yr OS | 5-yr PFS | 5-yr Relapse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | ||

| 0 | 14 | 91 (51, 99) | 83 (45, 95) | 17 (2,45) |

| 1 | 25 | 78 (54, 90) | 63 (38, 80) | 15 (3, 35) |

| 2 | 19 | 63 (38, 80) | 24 (17, 46) | 61 (32, 80) |

| >=3 | 18 | 22 (7, 43) | 6 (0.4, 22) | 72 (42, 88) |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.00002 |

Figure 2. Prognostic Score.

A. 5-year PFS based on prognostic score: 83% for Score 0, 63% for Score 1, 24% for Score 2, and 6% for Score >= 3 (p<0.0001). B. 5-year OS based on prognostic score: 91% for Score 0, 78% for Score 1, 63% for Score 2, and 22% for Score >= 3 (p<0.0001). C. 5-year cumulative incidence of relapse based on prognostic score: 17% for Score 0, 15% for Score 1, 61% for Score 2, and 72% for Score >= 3 (p=0.00002).

DISCUSSION

The optimal timing of HSCT in the treatment of CLL remains controversial and has become even more difficult with the advent of highly effective novel therapies including the kinase inhibitors ibrutinib and GS1101. Due to its ongoing risks, HSCT is often delayed until patients have been multiply treated and have refractory disease, although a recent retrospective comparison study suggested that even in that context, HSCT had survival benefit compared to conventional therapy(36). Given this typical delay, however, relapse rates after HSCT have remained significant. In this report, we explored the role of dose intensity in transplantation outcome through a retrospective analysis of all CLL patients who underwent allogeneic HSCT from 6/6 or better HLA matched adult donors at the DFCI/BWCC between 1998 and 2009. In the entire cohort, PFS and OS were not different between RIC and MAC approaches. In part this finding may result from the use of RIC HSCT primarily in heavily pretreated higher risk patients in the earlier years. As experience was gained, RIC has been used in a general patient population, resulting in similar patient characteristics between the two groups. Thus, since 2004, a notable difference in OS between the two groups, with an improved but not statistically different PFS, has become apparent. This improvement is due to decreases in both NRM and relapse in RIC patients, with minimal change in NRM in MAC patients. These findings suggest that the higher NRM of MAC conditioning remains prohibitive and our ability to select a group of patients likely to survive and potentially benefit from MAC HSCT for CLL remains limited. This appears true despite the fact that virtually all the MAC survivors were cured. Thus, RIC HSCT remains the transplantation of choice in this patient population. From our dataset we have developed a prognostic model to further risk stratify patients for RIC HSCT, with the lowest risk group having an extremely favorable 83% PFS at 5 years. This simple prognostic score is based on pre-transplantation characteristics and separates patients very effectively based on outcomes, including PFS, OS and relapse.

Even in the entire patient population, the outcomes of this RIC approach are extremely favorable, with 63% overall survival, and particularly so in the cohort since 2004, with 83% overall survival at 5 years. In part these outcomes are due to the notable safety of this RIC approach, particularly since 2004, when NRM at 5 year follow-up is 9.5%, significantly lower than NRM reported previously by ourselves and many others(22, 25, 28, 37). Similar improvements were not seen in the MAC subgroup even in the period since 2004. The RIC patient population did change after 2004, with more patients in remission at HSCT (72% vs 56% earlier). These remissions were mostly partial rather than complete, however, and the median number of prior therapies did not differ between the two periods (p=0.76). Our analysis did not identify any significant predictors of NRM due in part to the small number of NRM events. The use of sirolimus for GVHD prophylaxis became routine at DFCI since 2004 and may have contributed, as acute GVHD was decreased after RIC HSCT.

Recent studies have raised the possibility that RIC HSCT may be associated with a higher relapse rate(29), but we did not observe that in our analysis. Thus RIC HSCT benefited not just from reduced NRM but also from a decline in relapse rate from 40% in the overall group to 26% in the 2004–2009 population, similar to the low relapse rate in another recent report(37). The favorable relapse rate may be related in part to the higher percentage of patients in partial remission at HSCT, since persistent significant disease burden at HSCT has been repeatedly associated with increased relapse(25, 26, 28). Despite this improvement, however, relapse does remain the primary cause of treatment failure. New approaches are required to address it, including the use of novel therapies like the kinase inhibitors ibrutinib and GS1101, either to achieve deeper remission prior to HSCT or to help induce or maintain remission after HSCT.

Until then, improved patient selection may enhance outcomes. The primary predictors of relapse in this study were markers of ongoing disease at HSCT, specifically absence of remission, elevated LDH and lymphocyte count. From these variables, we were able to develop a prognostic score which successfully stratifies patients with very different outcomes after RIC HSCT and which may allow us to better determine the timing of HSCT in individual patients. Although strongly associated with outcome in our cohort, we nonetheless anticipate validating this score in independent cohorts to ensure its broad applicability.

Recent reports have suggested an adverse effect of complex cytogenetics on transplantation outcome(35). Due to missing data the power for the analysis of cytogenetic effects was limited. However, many patients in our cohort with complex cytogenetics, del17p, or del11q are still alive many years after RIC, suggesting that RIC HSCT can certainly result in long-term survival in these patient subgroups. Larger studies will be required to determine whether the rate of long-term survival is truly comparable between these high risk subgroups and lower risk subgroups.

In this study we saw no apparent effect of sirolimus-containing GVHD prophylaxis on relapse, although we have previously observed a beneficial effect in all lymphoid malignancies(38). The effects of sirolimus on both NRM and relapse in our study are difficult to differentiate from the effects of transplantation year, because sirolimus is closely associated with HSCT since 2004. For that reason we await the results of our ongoing multicenter randomized trial to draw more definitive conclusions about the impact of sirolimus.

The strength of our study is our long term follow-up of a relatively large cohort of HSCT patients with heavily pretreated CLL. The major weakness of our study is the changing patient population over time, as with any retrospective analysis. Significant systematic differences between the MAC and RIC patients are impossible to avoid, and even the RIC patient population has likely evolved in more recent years. Nonetheless, these limitations do not negate the extremely favorable findings in our recent RIC HSCTs, now with five year follow-up.

Our data suggest that recent changes in the approach to RIC HSCT, including employing HSCT earlier in the disease course or when the disease is in better control through conventional therapy, have resulted in significantly improved outcomes. The excellent long-term OS that we observe, resulting from recent improvements in both NRM and relapse, justifies the consideration of RIC HSCT earlier in the disease course of high-risk CLL. Although CLL is perceived as an indolent disease, most patients who require therapy, particularly those with high risk prognostic markers, will die of their disease, and median survival after either BR or FCR as a third-line regimen on a clinical trial has been reported to be 34 and 47 months, respectively(5, 6). With the recent encouraging results with ibrutinib and GS1101, the decision about the timing of transplant has become even more difficult for patients and physicians. Currently, however, follow-up with these drugs is still short, and the degree to which they may alter the natural history of standard CLL therapy is unclear. These drugs may also ultimately be able to further improve transplant outcomes by inducing better remissions prior to transplant or by reducing relapse after transplant. Meanwhile, our results suggest that the safety of RIC HSCT is now such that it should be considered earlier in the course of relapsed disease, when patients are healthier, deeper remissions are achievable, and long-term outcomes are therefore likely to be similar to those reported here.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the nurses, medical oncology fellows, house staff and social workers of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital for their excellent care of these patients. We thank the staff of the Connell-O’Reilly Cell Manipulation Laboratory and the Blood Component Laboratory of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute for processing stem cells for these patients, and the data management staff for their tireless work in maintaining the DFCI BMT clinical data repository, without which this project would not be possible. This work was supported by NIH grants K23 CA115682-01 to JRB, PO1 HL070149, PO1 CA81538 to JGG, A129530 to RJS, P01 CA142106 to JHA, and by the Jock and Bunny Adams Research and Education Endowment and the Ted and Eileen Pasquarello Research Fund. JRB is a Scholar of the American Society of Hematology as well as a Scholar in Clinical Research of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society

Footnotes

Presented in part at the Annual Meeting of ASH, December 2008

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTIONS

JRB, HTK, JHA and EPA designed the research. JRB, HTK, PA, CC, DCF, VH, JK, JR, CW, JHA, RJS, JGG and EPA performed the research. PA, CC, DCF, VH, JK, JR, JHA, RJS, JGG and EPA enrolled patients. JRB and HTK analyzed the data. JRB and HTK wrote the paper with input from PA, JHA, RJS, JGG and EPA.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Wierda W, O’Brien S, Wen S, Faderl S, Garcia-Manero G, Thomas D, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab for relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(18):4070–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.516. Epub 2005/03/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keating MJ, O’Brien S, Albitar M, Lerner S, Plunkett W, Giles F, et al. Early results of a chemoimmunotherapy regimen of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab as initial therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(18):4079–88. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.051. Epub 2005/03/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrd JC, Rai K, Peterson BL, Appelbaum FR, Morrison VA, Kolitz JE, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine may prolong progression-free survival and overall survival in patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: an updated retrospective comparative analysis of CALGB 9712 and CALGB 9011. Blood. 2005;105(1):49–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0796. Epub 2004/05/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keating MJ, Flinn I, Jain V, Binet JL, Hillmen P, Byrd J, et al. Therapeutic role of alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) in patients who have failed fludarabine: results of a large international study. Blood. 2002;99(10):3554–61. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3554. Epub 2002/05/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer K, Cramer P, Busch R, Stilgenbauer S, Bahlo J, Schweighofer CD, et al. Bendamustine combined with rituximab in patients with relapsed and/or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multicenter phase II trial of the German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Study Group. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(26):3559–66. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.8061. Epub 2011/08/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badoux XC, Keating MJ, Wang X, O’Brien SM, Ferrajoli A, Faderl S, et al. Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab chemoimmunotherapy is highly effective treatment for relapsed patients with CLL. Blood. 2011;117(11):3016–24. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-304683. Epub 2011/01/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dreger P, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, Ritgen M, Krober A, Kneba M, et al. The prognostic impact of autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a risk-matched analysis based on the VH gene mutational status. Blood. 2004;103(7):2850–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1549. Epub 2003/12/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gribben JG, Zahrieh D, Stephans K, Bartlett-Pandite L, Alyea EP, Fisher DC, et al. Autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantations for poor-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2005;106(13):4389–96. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1778. Epub 2005/09/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavletic ZS, Bierman PJ, Vose JM, Bishop MR, Wu CD, Pierson JL, et al. High incidence of relapse after autologous stem-cell transplantation for B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology/ESMO. 1998;9(9):1023–6. doi: 10.1023/A:1008474526373. Epub 1998/11/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michallet M, Dreger P, Sutton L, Brand R, Richards S, van Os M, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results of European intergroup randomized trial comparing autografting versus observation. Blood. 2011;117(5):1516–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-308775. Epub 2010/11/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sutton L, Chevret S, Tournilhac O, Divine M, Leblond V, Corront B, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation as a first-line treatment strategy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial from the SFGM-TC and GFLLC. Blood. 2011;117(23):6109–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-317073. Epub 2011/03/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, Fink AM, Busch R, Mayer J, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase. 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1164–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61381-5. Epub 2010/10/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tam CS, O’Brien S, Wierda W, Kantarjian H, Wen S, Do KA, et al. Long-term results of the fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab regimen as initial therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;112(4):975–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140582. Epub 2008/04/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michallet M, Corront B, Hollard D, Gratwohl A, Milpied N, Dauriac C, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 17 cases. Report from the EBMTG. Bone marrow transplantation. 1991;7(4):275–9. Epub 1991/04/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khouri IF, Keating MJ, Vriesendorp HM, Reading CL, Przepiorka D, Huh YO, et al. Autologous and allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: preliminary results. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1994;12(4):748–58. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.4.748. Epub 1994/04/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rabinowe SN, Soiffer RJ, Gribben JG, Daley H, Freedman AS, Daley J, et al. Autologous and allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for poor prognosis patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1993;82(4):1366–76. Epub 1993/08/15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dreger P, Montserrat E. Autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantation for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia: official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, UK. 2002;16(6):985–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402530. Epub 2002/06/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michallet M, Archimbaud E, Bandini G, Rowlings PA, Deeg HJ, Gahrton G, et al. HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplantation in younger patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry. Annals of internal medicine. 1996;124(3):311–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-3-199602010-00005. Epub 1996/02/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreno C, Villamor N, Colomer D, Esteve J, Martino R, Nomdedeu J, et al. Allogeneic stem-cell transplantation may overcome the adverse prognosis of unmutated VH gene in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(15):3433–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pavletic ZS, Arrowsmith ER, Bierman PJ, Goodman SA, Vose JM, Tarantolo SR, et al. Outcome of allogeneic stem cell transplantation for B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Bone marrow transplantation. 2000;25(7):717–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702237. Epub 2000/04/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toze CL, Galal A, Barnett MJ, Shepherd JD, Conneally EA, Hogge DE, et al. Myeloablative allografting for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: evidence for a potent graft-versus-leukemia effect associated with graft-versus-host disease. Bone marrow transplantation. 2005;36(9):825–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705130. Epub 2005/09/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caballero D, Garcia-Marco JA, Martino R, Mateos V, Ribera JM, Sarra J, et al. Allogeneic transplant with reduced intensity conditioning regimens may overcome the poor prognosis of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia with unmutated immunoglobulin variable heavy-chain gene and chromosomal abnormalities (11q- and 17p-) Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;11(21):7757–63. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0941. Epub 2005/11/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delgado J, Thomson K, Russell N, Ewing J, Stewart W, Cook G, et al. Results of alemtuzumab-based reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a British Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation Study. Blood. 2006;107(4):1724–30. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3372. Epub 2005/10/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schetelig J, van Biezen A, Brand R, Caballero D, Martino R, Itala M, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for chronic lymphocytic leukemia with 17p deletion: a retrospective European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation analysis. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(31):5094–100. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.2982. Epub 2008/08/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorror ML, Storer BE, Sandmaier BM, Maris M, Shizuru J, Maziarz R, et al. Five-year follow-up of patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation after nonmyeloablative conditioning. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(30):4912–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4757. Epub 2008/09/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dreger P, Dohner H, Ritgen M, Bottcher S, Busch R, Dietrich S, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation provides durable disease control in poor-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia: long-term clinical and MRD results of the German CLL Study Group CLL3X trial. Blood. 2010;116(14):2438–47. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275420. Epub 2010/07/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khouri IF, Bassett R, Poindexter N, O’Brien S, Bueso-Ramos CE, Hsu Y, et al. Nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation in relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Long-Term Follow-Up, Prognostic Factors, and Effect of Human Leukocyte Histocompatibility Antigen Subtype on Outcome. Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.26091. Epub 2011/04/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown JR, Kim HT, Li S, Stephans K, Fisher DC, Cutler C, et al. Predictors of improved progression-free survival after nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation for advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12(10):1056–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.06.004. Epub 2006/11/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dreger P, Brand R, Milligan D, Corradini P, Finke J, Lambertenghi Deliliers G, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning lowers treatment-related mortality of allogeneic stem cell transplantation for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a population-matched analysis. Leukemia: official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, UK. 2005;19(6):1029–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403745. Epub 2005/04/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, Baron F, Sandmaier BM, Maloney DG, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106(8):2912–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004. Epub 2005/07/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arora M, Nagaraj S, Witte J, DeFor TE, MacMillan M, Burns LJ, et al. New classification of chronic GVHD: added clarity from the consensus diagnoses. Bone marrow transplantation. 2009;43(2):149–53. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.305. Epub 2008/09/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone marrow transplantation. 1995;15(6):825–8. Epub 1995/06/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, Leupolt E, Krober A, Bullinger L, et al. Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2000;343(26):1910–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432602. Epub 2001/01/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Grever M, Kay N, Keating MJ, O’Brien S, et al. National Cancer Institute-sponsored Working Group guidelines for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: revised guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 1996;87(12):4990–7. Epub 1996/06/15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaglowski SM, Heerema NA, Elder P, Byrd JC, Devine S, Andritsos LA. Increasing Genetic Complexity Predicts for Inferior Outcomes Following Reduced-Intensity Conditioning Allogeneic Transplant for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2011;118(21):3090. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delgado J, Pillai S, Phillips N, Brunet S, Pratt G, Briones J, et al. Does reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation confer a survival advantage to patients with poor prognosis chronic lymphocytic leukaemia? A case-control retrospective analysis. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology/ESMO. 2009;20(12):2007–12. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp259. Epub 2009/07/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peres E, Braun T, Krijanovski O, Khaled Y, Levine JE, Yanik G, et al. Reduced intensity versus full myeloablative stem cell transplant for advanced CLL. Bone marrow transplantation. 2009;44(9):579–83. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.61. Epub 2009/03/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armand P, Gannamaneni S, Kim HT, Cutler CS, Ho VT, Koreth J, et al. Improved survival in lymphoma patients receiving sirolimus for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(35):5767–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7279. Epub 2008/11/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.