Abstract

Recurrence and metastasis result in a poor prognosis for breast cancer patients. Recent studies have demonstrated that microRNAs (miRNAs) play vital roles in the development and metastasis of breast cancer. In this study, we investigated the therapeutic potential of miR-34a in breast cancer. We found that miR-34a is downregulated in breast cancer cell lines and tissues, compared with normal cell lines and the adjacent nontumor tissues, respectively. To explore the therapeutic potential of miR-34a, we designed a targeted miR-34a expression plasmid (T-VISA-miR-34a) using the T-VISA system, and evaluated its antitumor effects, efficacy, mechanism of action, and systemic toxicity. T-VISA-miR-34a induced robust, persistent expression of miR-34a, and dramatically suppressed breast cancer cell growth, migration, and invasion in vitro by downregulating the protein expression levels of the miR-34a target genes E2F3, CD44, and SIRT1. In an orthotopic mouse model of breast cancer, intravenous injection of T-VISA-miR-34a:liposomal complex nanoparticles significantly inhibited tumor growth, prolonged survival, and did not induce systemic toxicity. In conclusion, T-VISA-miR-34a lead to robust, specific overexpression of miR-34a in breast cancer cells and induced potent antitumor effects in vitro and in vivo. T-VISA-miR-34a may provide a potentially useful, specific, and safe-targeted therapeutic approach for breast cancer.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common disease in females worldwide, with 1.38 million new cases diagnosed and leading to 458,100 deaths in 2008.1 Although the prognosis has improved due to advances in diagnosis, surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy,2,3 chemotherapy resistance and metastasis remain major challenges in breast cancer therapy.2,3,4 Conventional therapeutic strategies have little ability to eliminate the chemotherapy-resistant or metastatic cells which lead to breast cancer recurrence or distant relapse.5 Therefore, it is necessary to develop novel, targeted therapeutic strategies to treat breast cancer more effectively.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, noncoding RNAs which function as pivotal regulators of gene expression by binding to the 3′ untranslated region of their target mRNAs, via Watson-Crick complementarities between positions 2–8 of the miRNA (relative to the 5′ end), to promote mRNA degradation or inhibit mRNA transcription and/or translation.6 Most miRNAs have the potential to target a variety of genes. Increasing evidence indicates that miRNAs play critical roles in a number of biological processes, including development, cell proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, disease survival, and cell death.6,7,8,9 Furthermore, aberrantly expressed miRNAs can function as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors, and a large number of miRNAs are associated with the pathogenesis or prognosis of cancer.10,11,12

A number of miRNAs such as let-7, miR-15/16, miR-29, miR-34a/b/c, and miR-122 are downregulated and function as tumor suppressors in various human cancers.12 miR-34a, located on chromosome 1p36.22, is one of the most characterized tumor suppressor miRNAs and is an important component of the p53 tumor suppressor network.13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 Ectopic overexpression of miR-34a can induce apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and senescence, to inhibit cancer regeneration, migration, and metastasis.19,21 Indeed, according to multiple experimentally validated studies, miR-34a regulates a variety of target mRNAs involved in the cell cycle, cell proliferation, senescence, migration, and invasion, such as cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6), E2F transcription factor 3 (E2F3), Cyclin E2, hepatocyte growth factor receptor (MET), B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin-1 (SIRT1), Myc, Notch, and CD44.19,21

The human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT; T) gene is activated in a number of invasive cancers but is repressed in normal somatic tissues or benign tumors.22 In our previous work, we developed a versatile targeting vector “VISA ” (VP16-GAL4-WPRE integrated systemic amplifier; WPRE, the post-transcriptional regulatory element of the woodchuck hepatitis virus) based on an engineered expression vector, which can enhance cancer-specific promoter activity by 100-fold and prolong the duration of gene expression.23 This system has been successfully applied in preclinical models of pancreatic, lung, ovarian, and breast cancer.23,24,25 T-VISA (hTERT promoter-driven VP16-Gal4-WPRE integrated systemic amplifier) has been proven to be a powerful vector for specific, targeted expression of adenovirus 5 E1A gene (E1A, an adenoviral type 5 transcription factor that possesses anticancer properties) in ovarian cancer cells, which lead to reduced tumor growth.24

In this study, we analyzed the expression of miR-34a in breast cancer cell lines and breast cancer tissues. Then, we engineered a T-VISA-miR-34a plasmid, to drive expression of miR-34a in breast cancer cells under control of the hTERT promoter, which is specifically activated in breast cancer cells. Targeted expression of miR-34a using T-VISA-miR-34a lead to the downregulation of a number of miR-34a target genes and significantly suppressed breast cancer cell growth, migration, and invasion in vitro. Finally, we evaluated the therapeutic effect of T-VISA-miR-34a in a mouse model of breast cancer using a liposomal delivery system and live imaging.

Results

MiR-34a is downregulated in human breast cancer

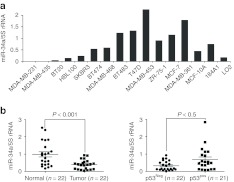

MiR-34a has been reported to be downregulated in a variety of cancers, including breast cancer.26 First, a series of human breast cancer cell lines was analyzed to assess the expression profile of miR-34a in breast cancer using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (Figure 1a). Compared with the two immortalized normal mammary epithelial cell lines (184A1, MCF-10A),27 five of the breast cancer cell lines showed reduced miR-34a expression (by up to 60%), especially the triple-negative breast cancer cell MDA-MB-231 (<5% of means of 184A1 and MCF-10A cells).

Figure 1.

MiR-34a is downregulated in breast cancer cell lines and human breast cancer and is associated with p53 expression. (a) Expression of miR-34a in 13 breast cancer cell lines and 3 normal cell lines; miR-34a expression was determined by qRT-PCR and normalized to the endogenous control 5S rRNA. (b) Expression of miR-34a in 22 paired human breast cancer specimens and the corresponding paired normal adjacent tissues. (c) Expression levels of miR-34a in 43 human breast cancer specimens with different p53 expression; p53 expression was assessed by IHC. Statistical analysis was performed using the paired t-test. IHC, immunohistochemistry; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription-PCR; rRNA, ribosomal RNA.

We also assessed the expression of miR-34a in a series of 22 human primary breast cancer tissues and the paired normal adjacent tissues (NATs). Compared with the NATs, 19 of the 22 (86.4%) tumor samples had lower levels of miR-34a expression; the median miR-34a expression level in breast cancer was 2.5-fold lower than the paired NATs (median values = 0.3847 and 0.9771, respectively; Figure 1b). According to a previous report,20 miR-34a expression levels correlate with the p53 transcriptional activity, indicated that miR-34a is a direct transcriptional target of p53.

To verify whether the miR-34a expression level corresponds with the transcriptional activity of p53 in human breast cancer, we determined the expression levels of p53 using immunohistochemical staining in a total of 43 human primary breast cancer tissues. Compared with the p53-negative group, the tumors of the p53-positive breast cancer patients had a higher miR-34a expression level (P < 0.05; Figure 1c).

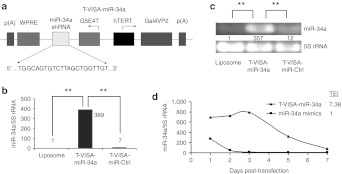

T-VISA-miR-34a induces robust and persistent expression of miR-34a in breast cancer cells

To investigate the potential of miR-34a gene therapy, we engineered a T-VISA-miR-34a plasmid which could selectively express miR-34a in cancer cells, but not in normal cells (Figure 2a), and verified that the miR-34a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) nucleotide sequences were correctly inserted into T-VISA by sequence analysis. T-VISA-miR-Ctrl, which expresses shRNA against green fluorescent protein, was used as a negative control. We transfected the T-VISA-miR-34a plasmid into MDA-MB-231 cells using a DOTAP:cholesterol liposomal complex, and assessed the expression of miR-34a by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. Compared with control untransfected cells, T-VISA-miR-34a enhanced the expression of miR-34a by up to 420-fold; T-VISA-miR-Ctrl did not induce miR-34a expression (Figure 2b); these results were confirmed by reverse transcription-PCR (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Construction of the T-VISA-miR-34a plasmid. (a) Schematic diagram of T-VISA-miR-34a constructed using the pUK21 backbone. (b) The T-VISA-miR-34a plasmid leads to robust expression of miR-34a; miR-34a expression was measured in liposomal complex, T-VISA-miR-Ctrl, and T-VISA-miR-34a–transfected MDA-MB-231 cells using qRT-PCR and normalized to 5S rRNA. (c) RT-PCR confirmation of miR-34a expression in liposomal complex, T-VISA-miR-Ctrl, and T-VISA-miR-34a–transfected MDA-MB-231 cells. (d) Kinetics of miR-34a expression in T-VISA-miR-34a–transfected and miR-34a mimic–transfected MDA-MB-231 cells; miR-34a expression was measured by qRT-PCR and normalized to 5S rRNA. The data represent the mean values of two independent experiments. **P < 0.05 with the use of paired t-test. hTERT, human telomerase reverse transcriptase; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription-PCR; rRNA, ribosomal RNA, shRNA, short hairpin RNA; TEI, total expression index.

Previous reports demonstrated that the VISA vector can prolong the duration of transgene expression, compared with cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter.23 To test whether the T-VISA vector could prolong the expression of miR-34a, we measured the kinetics of miR-34a expression in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with T-VISA-miR-34a or miR-34a mimics. Compared with miR-34a mimics, T-VISA-miR-34a significantly prolonged the duration of miR-34a expression (Figure 2d). T-VISA-miR-34a lead to sevenfold higher expression of miR-34a, compared with the miR-34a mimics (as measured by the total expression index). In addition, the half-life of T-VISA-miR-34a expression activity was 4.6 days, compared with only 1.6 days for the miR-34a mimics.

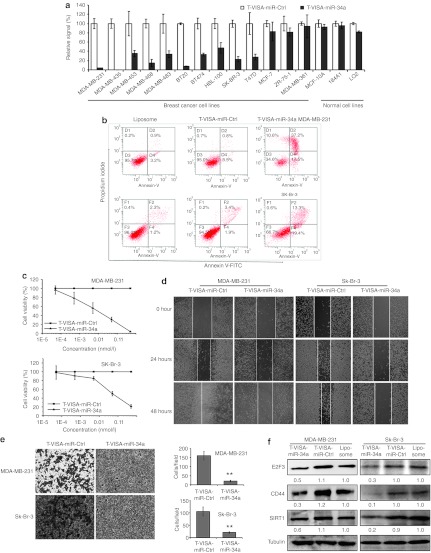

T-VISA-miR-34a inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation

Previously, overexpression of miR-34a was reported to induce apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, senescence, invasion, and migration in human cancer cells,19,21 suggesting that downregulation of miR-34a might play a vital role in the development of a malignant phenotype. Therefore, we speculated that ectopic restoration of miR-34a expression might interfere with the oncogenic properties of breast cancer cells. To evaluate the potential antitumor effects of T-VISA-miR-34a in breast cancer in vitro, we transiently co-transfected 13 human breast cancer cell lines and 3 normal cell lines (184A1, MCF-10A, LO2) with T-VISA-miR-34a plus the indicator plasmid pGL3-CMV-Luc. The inhibitory effects of T-VISA-miR-34a on cell proliferation were assessed by assaying luciferase activity 72 hours after transfection (Figure 3a). T-VISA-miR-34a significantly suppressed proliferation in the majority of breast cancer cell lines, but had no obvious effects in MCF-7, ZR-75-1, and MDA-MB-361 cells or the normal cell lines.

Figure 3.

T-VISA-miR-34a exerts an inhibitory effect in multiple breast cancer cell lines. (a) T-VISA-miR-34a effectively inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation. The results are expressed as a percentage of T-VISA-miR-Ctrl–transfected cells (100%) and represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. (b) Annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide staining and FACS quantification of the number of apoptotic cells in MDA-MB-231 and SK-Br-3 cells transfected with liposomal complexes, T-VISA-miR-Ctrl or T-VISA-miR-34a. (c) Kinetics of the effect of T-VISA-miR-34a on breast cancer cell viability. MDA-MB-231 and SK-Br-3 cells were transiently co-transfected with the indicated liposomal complexes, T-VISA-miR-Ctrl or T-VISA-miR-34a and CMV-Luc plasmid DNA and luciferase activity was measured as a measure of cell viability at 72 hours post-transfection. Data represent the mean ± SD of two independent experiments. (d) Wound healing assay in MDA-MB-231 and SK-Br-3 cells transfected with liposomal complexes, T-VISA-miR-Ctrl or T-VISA-miR-34a. (e) Transwell migration assay in MDA-MB-231 and SK-Br-3 cells transfected with liposomal complexes, T-VISA-miR-Ctrl or T-VISA-miR-34a. (f) Western blot analysis of the endogenous levels of E2F3, CD44, and SIRT1 in MDA-MB-231 and SK-Br-3 cells transfected with liposomal complexes, T-VISA-miR-Ctrl or T-VISA-miR-34a; tubulin served as an internal control. **P < 0.05 with the use of paired t-test. FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate.

We used Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocynate/propidium iodide staining and FACS to determine whether T-VISA-miR-34a induced apoptosis and/or cell death in MDA-MB-231 and SK-Br-3 cells. T-VISA-miR-34a–transfected cells had an obviously higher ratio of apoptotic and dead cells (Figure 3b). Furthermore, compared with T-VISA-miR-Ctrl–transfected cells, T-VISA-miR-34a lead to a dose-dependent reduction in the viability of breast cancer cells (Figure 3c), with an IC50 of 0.01 nmol/l in MDA-MB-231 cells. In addition, T-VISA-miR-34a inhibited MDA-MB-231 and SK-Br-3 cell migration (Figure 3d) and invasion (Figure 3e). Furthermore, transfection of MDA-MB-231 and SK-Br-3 cells with T-VISA-miR-34a reduced the protein expression levels of the miR-34a target genes E2F3, CD44, and SIRT1 (Figure 3f).

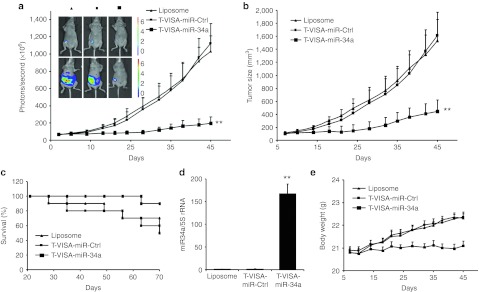

T-VISA-miR-34a inhibits tumor growth in an orthotopic mouse model of human breast cancer

To investigate whether T-VISA-miR-34a could repress breast cancer growth in vivo, we inoculated luciferase-expressing triple-negative MDA-MB-231-Luc breast cancer cells into the mammary fat pads of female BALB/c nude mice, to establish an orthotopic model of breast cancer. When the tumors established, liposomal complexes of T-VISA-miR-34a or T-VISA-miR-Ctrl (15 µg) were injected via tail vein injection twice a week for 3 weeks. The tumors were noninvasively monitored twice a week over a period of 5 weeks using the IVIS in vivo imaging system.

Compared with T-VISA-miR-Ctrl negative control-treated mice, the imaging revealed a significant reduction in the signal from tumors of the T-VISA-miR-34a–treated mice from 1 week after the start of treatment (Figure 4a). T-VISA-miR-34a also lead to a reduced tumor size (Figure 4b) and mouse body weight (Figure 4e), compared with the liposomal-treated and T-VISA-miR-Ctrl groups. Furthermore, the lifespan of the mice treated with T-VISA-miR-34a was significantly longer than the mice treated with T-VISA-miR-Ctrl (Figure 4c). We also found that the expression level of miR-34a was significantly higher in the tumors of the T-VISA-miR-34a group, compared with the other treatment groups (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

T-VISA-miR-34a inhibits tumor growth in an orthotopic mouse model of breast cancer. Nude mice bearing MDA-MB-231-Luc tumors were systemically administered liposomal plasmid DNA complexes as indicated twice weekly for three consecutive weeks (n = 10 mice/group). (a) T-VISA-miR-34a inhibits breast cancer tumor growth. Tumor photon signals were quantified using the Xenogen IVIS in vivo live imaging system before treatment (top row) and after 45 days (bottom row); values are the mean ± SD. (b) Tumor volume. (c) Kaplan–Meier survival curves; survival was monitored up to 70 days after tumor transplantation. (d) qRT-PCR analysis of miR-34a expression in xenograft tumors. (e) Body weight of nude mice bearing MDA-MB-231-Luc tumors treated (n = 10 mice/group). **P < 0.05 with the use of paired t-test. qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription-PCR; rRNA, ribosomal RNA.

Systemic administration of T-VISA-miR-34a leads to limited acute toxicity

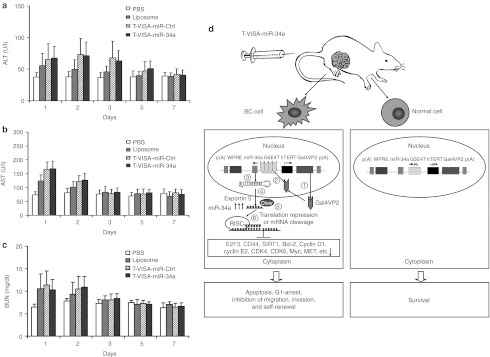

To assess the potential toxicity of systemic administration of the T-VISA plasmid DNA liposomal complexes, we intravenously injected normal mice with 50 µg T-VISA plasmid DNA in liposomal complexes. All of the mice were alive after 7 days, with no evidence of toxic effects observed after treatment with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), liposomal complexes, T-VISA-miR-Ctrl or T-VISA-miR-34a during the experiment (7 days). As shown in Figure 5a–c, the serum levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and blood urea nitrogen values remained within the reference ranges in all treatment groups, suggesting that T-VISA-miRNA treatment was well tolerated. In addition, all of the mice exhibited normal behavior, as determined by their activity level and grooming behavior throughout the 7-day study. Taken together this data indicates that T-VISA-miR-34a induced only minimal toxic effects in normal animals.

Figure 5.

Systemic administration of T-VISA-miR-34a does not induce acute toxicity in mice and the proposed working model for targeted T-VISA-miR-34a therapy. (a–c) Kinetics of the serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 1–7 days after a single intravenous injection of 50 µg liposomal:plasmid DNA. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 10 mice/group). (d) Schematic diagram of the working model for the T-VISA-miR-34a targeting system in breast cancer. (1) The hTERT promoter drives expression of the GAL4-VP2 (two copies of VP16)30 fusion protein specifically in breast cancer cells, but not in normal cells; (2) GAL4-VP2 induces expression of the miR-34a shRNA transcripts; (3) miR-34a are expressed; (4) miR-34a are exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm by exportin 5; (5) miR-34a shRNA are processed further by Dicer to single-stranded mature miR-34a; (6) the mature miR-34a are incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which induces downregulation of miR-34a target genes leading to apoptosis and G1-arrest, and inhibition of migration, invasion, and self-renewal in breast cancer cells.19,21 BC cell, breast cancer cell; hTERT, human telomerase reverse transcriptase; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; shRNA, short hairpin RNA.

Discussion

Peurala et al. have shown that miR-34a as a tumor suppressor, which expression activation exerts an independent effect for a lower risk of recurrence or death in breast cancer.26 In the present study, we found that miR-34a is downregulated in breast cancer compared with the paired NATs. MiR-34a is an important component of the p53 tumor suppressor network;20 therefore, we speculated that the miR-34a expression levels may be associated with the expression of p53 in breast cancer. To investigate further, we analyzed the levels of miR-34a in 43 breast cancer patients with differing p53 expression levels. Our data revealed a significant correlation between p53 and miR-34a expression (Figure 1c). In addition, we also observed an association between miR-34a and the age of the patients; older patients had lower levels of miR-34a than the younger patients (median = 0.2856 and 0.6138, respectively), the reason for this difference is not clear. No other clinicopathological feature was associated with the expression of miR-34a in breast cancer (Supplementary Table S2).

Based on its ability to concurrently target and repress multiple genes involved in cell proliferation, the cell cycle, migration, invasion, and self-renewal, miR-34a-based gene therapy approaches are being developed for multiple types of cancer.14,16,17,18,19 The main strategies adopted for miRNA-based therapeutics are the use of synthesized oligonucleotides or virus-based constructs to either block the expression of oncogenic miRNAs or restore the expression of tumor suppressor miRNAs. However, in a similar manner to small-interfering RNA technology, miRNA-based therapeutics are also confronted by bottlenecks during early clinical development, such as problems with effective delivery, potential off-target effects, and safety.28

The hTERT (T) promoter can direct preferential transgene expression in cancer cells.29 However, hTERT promoter activity is much lower than the commonly used viral, nonspecific CMV promoter. To overcome this problem, we integrated the T promoter into our recently developed VISA system. The T-VISA system can dramatically amplify transgene expression without the use of viral promoters, such as the CMV promoter, which eliminates the risks associated with nonspecific viral promoter-mediated target gene expression. VISA is a composite system which contains two basic elements: the two-step transcriptional amplification system and the WPRE sequence. The two-step transcriptional amplification system can significantly augment the activity of the hTERT promoter. The potent transcriptional activator, GAL4-VP2 (two copies of VP16) driven by the cancer cell-specific hTERT promoter, can combine and activate expression of a reporter gene or therapeutic protein.23,30,31 GAL4-VP2 is a fusion protein comprising the DNA-binding domain of the yeast transcriptional activator GAL4 and the activation domain of the herpes simplex virus 1 activator VP16.30 WPRE can enhance transgene expression by inserting into the 3′ untranslated region of the coding sequence of the transgene, to increase the half-life of RNA transcripts.32 T-VISA–driven expression of E1A, an adenoviral type 5 transcription factor which possesses anticancer properties, exerted significant cancer-specific antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo.24 In order to further explore the potential clinical applications of miR-34a, we incorporated miR-34a shRNA into the powerful targeting T-VISA vector, to construct T-VISA-miR-34a to drive targeted expression of miR-34a in breast cancer cells.

First, we compared the expression of miR-34a in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells transiently transfected with T-VISA-miR-34a or the control plasmid T-VISA-miR-Ctrl using liposomal complexes. T-VISA-miR-34a–transfected cells exhibited significantly increased expression of miR-34a. Next, we tested the inhibitory effects of T-VISA-miR-34a in vitro. T-VISA-miR-34a significantly inhibited the proliferation of multiple breast cancer cells, including the triple-negative cell lines MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468, and the Her2-positive cell lines BT474 and SK-Br-3, but had no significant effect in normal cells and MCF-7, ZR-75-1, MDA-MB-361. Interestingly, those three breast cancer cell lines are p53 wild-type,33 miR-34a is a direct transcriptional target of p53, so we speculate miR-34a expression levels would be no significant difference in those three cancer cell lines, ours miR-34a expression levels results were consistent with this speculation (Figure 1a), and T-VISA-miR-34a would be no significant to p53 wild-type cancer cell lines. In addition, T-VISA-miR-34a induced apoptosis and cell death, and reduced the invasion and migration of MDA-MB-231 and SK-Br-3 cells.

Of the multiple miR-34a target genes,21 we selected E2F3, CD44, and SIRT1 to verify the effect of T-VISA-miR-34a on the suppression of miR-34a target genes. E2F3 is critical for the G1/S transition,21 SIRT1 is an NAD-dependent deacetylase associated with tumorigenesis and poor prognosis in breast cancer. CD44 encodes a multifunctional class I transmembrane glycoprotein, mainly associated with cell adhesion, proliferation, survival, motility, migration, angiogenesis, and differentiation, which is expressed at high levels in almost every cancer cell and has been identified as a breast cancer stem cell marker.34,35,36 Transfection of T-VISA-miR-34a reduced E2F3, CD44, and SIRT1 protein expression in MDA-MB-231 and SK-Br-3 cells.

Furthermore, we evaluated the antitumor efficacy of T-VISA-miR-34a in vivo, using an orthotopic mouse model of breast cancer. Notably, systemic administration of T-VISA-miR-34a liposomal complexes significantly suppressed tumor growth and prolonged the survival of mice, compared with T-VISA-miR-Ctrl. Most importantly, T-VISA-miR-34a was specifically and effectively expressed in the breast cancer cells, and was inhibited breast cancer cell growth in vivo. The specificity of T-VISA-miR-34a was further reflected by the safety profile of systemically delivered T-VISA-miR-34a:liposomal complexes in vivo, which had almost no toxic effects in healthy BALB/c mice.

In summary, our results demonstrate that the tumor suppressor miRNA miR-34a is downregulated in breast cancer. We engineered T-VISA-miR-34a, a highly breast cancer-specific expression vector, which could induce prolonged, high levels of miR-34a expression in vitro. Systemic delivery of T-VISA-miR-34a liposomal complexes lead to significant antitumor effects and prolonged survival in an orthotopic mouse model of triple-negative breast cancer, with minimal or no toxic effects. The mechanism of action of T-VISA-miR-34a in breast cancer is summarized in Figure 5d. Overall, this study demonstrates the feasibility of T-VISA-miR-34a liposomal complexes as a safe and highly effective therapeutic strategy for breast cancer, which is worthy of further development into clinical trials.

Materials and Methods

Patients and tissues. A total of 43 breast cancer tissues (clinicopathological parameters provided in the Supplementary Table S2), for which the paired normal adjacent tissues (NATs >2 cm from the tumor) were available for 22 cases, were obtained from biopsies at Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center (SYSUCC) (Guangzhou, China), fixed in RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX) immediately after biopsy and stored at −80 °C until use. The samples were histologically confirmed by hematoxylin and eosin staining and staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer and tumor-lymph node-metastasis classification system.37,38 Pathological diagnosis was verified by two different pathologists. Informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the study was approved by the research ethics committee of SYSUCC (reference number: YP-2009174).

Immunohistochemical staining. The formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned at 5 µm, deparaffinized, rehydrated through graded alcohols and subjected to antigen retrieval in heated citrate buffer. Following a blocking step, the slides were incubated with p53 primary antibody (1:150; Labvision, Fremont, CA), washed, biotinylated secondary antibody was applied and the immunocomplexes were visualized using an avidin-biotin complex immunoperoxidase system (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) with 0.03% diaminobenzidine as a chromagen and hematoxylin as the counterstain. Both external and internal controls were used to assess the quality of the immunohistochemistry reaction. If >10% of the cancer cells contained p53 nuclear immunoreactivity, the patient was classified as p53 positive; if <10% of the cancer cells contained p53 nuclear immunoreactivity, the patient was classified as p53 negative. Two pathologists who were blinded to all clinical information scored all specimens. Conflicts (about 5% of cases) were resolved by consensus.

Plasmid construction and purification. The mature human miR-34a sequences were obtained from the Sanger Center miRNA Registry (http://microrna.sanger.ac.uk/sequences/). To engineer the miR-34a expression plasmid, two complementary oligonucleotides containing Bgl II and Nhe I restriction sites (miR-34a shRNA-S, 5′-GAT CTG GCA GTG TCT TAG CTG GTT GTC TCG AGA CAA CCA GCT AAG ACA CTG CCA TTT TTG-3′ and miR-34a shRNA-AS, 5′-CTA GCA AAA ATG GCA GTG TCT TAG CTG GTT GTC TCG AGA CAA CCA GCT AAG ACA CTG CCA-3′) were annealed and purified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and the QIAquick Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The miR-34a shRNA was inserted into the Bgl II/Nhe I sites of the plasmid pGL3-T-VISA-Luc according to the standard molecular cloning protocols, then the T-VISA-miR-34a fragment of pGL3-T-VISA-miR-34a was subcloned into the Not I and Sal I sites of pUK21.39 The shRNAs against green fluorescent protein were designed and cloned into T-VISA in a similar manner, to create the negative control T-VISA-miR-Ctrl plasmid. All plasmid products were verified by DNA sequencing.

Plasmids were amplified in DH5α Escherichia coli and purified using the Endo-free Mega Prep Kit (Qiagen) in accordance with manufacturer's instructions. Plasmid DNA was dissolved in endotoxin-free TE buffer and quantified by spectrophotometry at 260 nm; the plasmid DNA was free of major protein and RNA contamination with an A260/A280 ratio between 1.8 and 2.0. The amount of endotoxin contamination was determined using a chromogenic Limulus amoebocyte clotting assay (QCL-1000 kit; BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD); all values were <10 endotoxin units/mg DNA.

Cell culture and transfection. MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-361, MDA-MB-435, MDA-MB-468, BT-20, BT-474, BT-483, MCF-7, HBL-100, AU565, SK-Br-3, T47D, and ZR-75-1 breast cancer cell lines, immortalized normal mammary epithelial cell lines (184A1, MCF-10A), and a normal liver cell line (LO2) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained according to the vendor's instructions. Luciferase-expressing MDA-MB-231 (MDA-MB-231-Luc) cells were kindly provided by Dr M.-C.H.40

Briefly, the cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 or Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10 % fetal bovine serum (GIBCO, Campinas, Brazil). MCF-10A cells were cultured in Keratinocyte-SFM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with pre-qualified human recombinant epidermal growth factor 1-53 (EGF 1-53; Invitrogen) and bovine pituitary extract (Invitrogen). Immortalized normal mammary epithelial cells 184A1 were grown in Mammary Epithelium Basal Medium (Clonetics, Walkersville, MD). All cells were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37 °C containing 5% CO2.

Cholesterol and 1, 2-bis(oleoyloxy)-3-(trimethyl ammonio) propane (DOTAP; Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL), were extruded and DOTAP:cholesterol liposomes were produced according to the protocol described by Templeton et al.41 The plasmid:liposomal complex sizes were ~140 nm; the zeta potential was 13 mV (Supplementary Table S1), and detailed methods are described in Supplementary Materials and Methods. Transient transfections were performed as previously described.23 Briefly, to evaluate the cell inhibitory effects, the cells were transiently co-transfected in 24-well plates with 1 µg of the T-VISA plasmid DNA plus 0.1 µg of CMV-Luc DNA using extruded DOTAP:cholesterol liposomes at an N/P ratio of 2:1 secons. For RNA or protein collection, the appropriate plasmid DNA or miRNAs mimics (synthesized and purified by RiboBio, Guangzhou, China) were complexed with DOTAP:cholesterol liposomes and transfected into cells cultured in 6-well plates; the cells were harvested at the appropriate time points.

RNA isolation and real-time PCR. Total RNA was extracted from flash-frozen tissue samples or cultured cells using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. MiR-34a-specific reverse transcription was performed using a specific stem-loop real-time PCR miRNA kit (RiboBio). After reverse transcription at 42 °C for 60 minutes followed by denaturation at 70 °C for 10 minutes, amplification and detection were performed on the ABI 7900HT instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the Platinum SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix-UDG system (Invitrogen). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate, and the expression of miR-34a was normalized to 5S ribosomal RNA. The quantity of miR-34a was calculated using the equation: relative quantity (RQ) = 2 − ΔΔCT.42

Western blot analysis. MDA-MB-231 and SK-Br-3 cells were transfected with the T-VISA plasmids, cultured for 72 hours and then harvested on ice using radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis and extraction buffer (25 mmol/l Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 150 mmol/l NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, protease inhibitor cocktail (Pierce, Rockford, IL)). Total cell extracts (20 µg protein) were separated using 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The membranes were incubated with mouse monoclonal antibody against human CD44 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Abcam) and the bands were detected using the Supersignal West Pico ECL chemiluminescence kit (Pierce) and Kodak X-ray film (Eastman Kodak, New York, NY); an anti-tubulin antibody (Boster, Wuhan, China) was used as a protein loading control.

Cell inhibitory assays. To determine the inhibitory effect of T-VISA-miR-34a, a series of breast cancer and normal cells seeded in 24-well plates (3 × 104 per well) were transiently co-transfected with DOTAP:cholesterol liposomal complexes containing 1 µg plasmid T-VISA plasmid DNA and 0.1 µg CMV-Luc (internal control). At 72 hours after transfection, the cells were harvested, lysed, and luciferase activity was assayed using the Dual-Glo luciferase assays kit (Promega, Madison, WI) as previously described.43 All analyses were performed in triplicate.

Flow cytometry. Annexin V/propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry were performed using the Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocynate Apoptosis Detection Kit (KeyGen, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. Briefly, 5 × 105 cells were washed in ice-cold PBS, resuspended in 50 µl of binding buffer and incubated with 2 µl of propidium iodide and 2 µl of Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocynate for 15 minutes in the dark at room temperature, washed and resuspended in 500 µl PBS. Flow cytometric analysis was performed immediately using a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Cell migration and invasion assays. For the scratch migration assay, the transfected cell monolayers were scratched using a standard 200 µl pipette tip, and serial photographs were captured at different time points using a phase contrast microscope (Olympus IX81; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Breast cancer cell invasion was assessed using Matrigel-coated Invasion Chambers (8 µm; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, the transfected cells were harvested, resuspended (~25,000 cells per well) in serum-free medium, and transferred to the upper chamber of the matrigel-coated inserts; media containing 10% fetal bovine serum was placed in the bottom chamber. The cells were incubated for 24 hours at 37 °C, then the cells on the upper surface were scraped and washed away, and the cells which had invaded to the lower surface were fixed and stained with 0.05% crystal violet for 30 minutes, counted under a microscope and the relative number of invading cells was calculated.

Tumor transplantation experiments. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with currently prescribed guidelines and under a protocol approved by the local ethics committee of SYSUCC. The mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free environment.

To investigate the antitumor effects of T-VISA-miR-34a in vivo, 30 athymic female BALB/c-nude mice (4–6 weeks old; Vital River Laboratories Animal, Beijing, China) were injected subcutaneously into the right fourth mammary gland with 5 × 106 MDA-MB-231-Luc cells in 100 µl PBS using a 30-gauge needle. Tumor formation was monitored by palpation and tumor size was measured twice per week using calipers. Tumor volume was calculated using the standard formula: tumor volume = (width2 × length × π)/6. When the tumors reached ~50 mm3, the mice were noninvasively imaged using the IVIS In Vivo Imaging System (Xenogen, Alameda, CA) to confirm tumor growth and then randomly assigned to one of three treatment groups (n = 10 mice per group): T-VISA-miR-Ctrl liposomal complexes (15 µg DNA), T-VISA-miR-34a liposomal complexes (15 µg DNA) or liposomal complexes. All groups received intravenous injections of 100 µl of plasmid:liposomal complexes twice weekly for three consecutive weeks. Mouse weight and tumor progression were monitored daily using the IVIS system equipped with Living Imaging software (Xenogen). The experiment was ended on day 70, the mice were euthanized by cervical vertebra dislocation, and the tumors and hearts were immediately harvested, weighed, and analyzed.

Analysis of acute toxicity. To study the acute toxicity induced by systemic administration of the plasmid:liposomal complexes, BALB/c mice were injected with a single dose of 100 µl plasmid:liposomal complexes containing 50 µg plasmid DNA via the lateral tail vein. Mouse morbidity, mortality, general health, and behavior were observed for 7 days. On 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7 days after the injection, the mice were anesthetized and blood was collected by retro-orbital bleeding using a heparinized microcapillary tube. The levels of serum aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and blood urea nitrogen were measured with an automatic analyzer (Roche Cobas Mira Plus; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) by the Biochemistry Laboratory of the Medical Laboratory Department, SYSUCC.

Statistical analysis. All values are presented as the mean ± SD. Data was analyzed using SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Analysis of variance was used to compare the differences among treatment groups and survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method. All statistical tests were two sided; the significance level was set at P < 0.05.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Table S1. Size and zeta potential of plasmid:liposome nanoparticles (N/P = 2:1). Table S2. The relationship between miR-34a expression and clinicopathological parameters in breast cancer. Materials and Methods.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 31030061), the Doctoral Fund of Ministry of Education of China (no. 20090171110078), and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou, China (no. 10C32060205). The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Size and zeta potential of plasmid:liposome nanoparticles (N/P = 2:1).

The relationship between miR-34a expression and clinicopathological parameters in breast cancer.

References

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E., and, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeg PS. Tumor metastasis: mechanistic insights and clinical challenges. Nat Med. 2006;12:895–904. doi: 10.1038/nm1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffer CL., and, Weinberg RA. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science. 2011;331:1559–1564. doi: 10.1126/science.1203543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera E., and, Gomez H. Chemotherapy resistance in metastatic breast cancer: the evolving role of ixabepilone. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12 suppl. 2:S2. doi: 10.1186/bcr2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumov GN, Townson JL, MacDonald IC, Wilson SM, Bramwell VH, Groom AC.et al. (2003Ineffectiveness of doxorubicin treatment on solitary dormant mammary carcinoma cells or late-developing metastases Breast Cancer Res Treat 82199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui M, Martello G., and, Piccolo S. MicroRNA control of signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:252–263. doi: 10.1038/nrm2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kouwenhove M, Kedde M., and, Agami R. MicroRNA regulation by RNA-binding proteins and its implications for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:644–656. doi: 10.1038/nrc3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esquela-Kerscher A., and, Slack FJ. Oncomirs – microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:259–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Pan X, Cobb GP., and, Anderson TA. microRNAs as oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Dev Biol. 2007;302:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon R, Marcucci G., and, Croce CM. Targeting microRNAs in cancer: rationale, strategies and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:775–789. doi: 10.1038/nrd3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calin GA, Sevignani C, Dumitru CD, Hyslop T, Noch E, Yendamuri S.et al. (2004Human microRNA genes are frequently located at fragile sites and genomic regions involved in cancers Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1012999–3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole KA, Attiyeh EF, Mosse YP, Laquaglia MJ, Diskin SJ, Brodeur GM.et al. (2008A functional screen identifies miR-34a as a candidate neuroblastoma tumor suppressor gene Mol Cancer Res 6735–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo E, Navarro A, Viñolas N, Marrades RM, Diaz T, Gel B.et al. (2009miR-34a as a prognostic marker of relapse in surgically resected non-small-cell lung cancer Carcinogenesis 301903–1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenz T, Mohr J, Eldering E, Kater AP, Bühler A, Kienle D.et al. (2009miR-34a as part of the resistance network in chronic lymphocytic leukemia Blood 1133801–3808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J, Zhou L, Xie QF, Xie HY, Wei XY, Gao F.et al. (2010The impact of miR-34a on protein output in hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells Proteomics 101557–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranha MM, Santos DM, Solá S, Steer CJ., and, Rodrigues CM. miR-34a regulates mouse neural stem cell differentiation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Kelnar K, Liu B, Chen X, Calhoun-Davis T, Li H.et al. (2011The microRNA miR-34a inhibits prostate cancer stem cells and metastasis by directly repressing CD44 Nat Med 17211–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TC, Wentzel EA, Kent OA, Ramachandran K, Mullendore M, Lee KH.et al. (2007Transactivation of miR-34a by p53 broadly influences gene expression and promotes apoptosis Mol Cell 26745–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermeking H. The miR-34 family in cancer and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:193–199. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, Harley CB, West MD, Ho PL.et al. (1994Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer Science 2662011–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X, Xia W, Li Z, Kuo HP, Liu Y, Li Z.et al. (2007Targeted expression of BikDD eradicates pancreatic tumors in noninvasive imaging models Cancer Cell 1252–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X, Hsu JL, Choi MG, Xia W, Yamaguchi H, Chen CT.et al. (2009A novel hTERT promoter-driven E1A therapeutic for ovarian cancer Mol Cancer Ther 82375–2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang JY, Hsu JL, Meric-Bernstam F, Chang CJ, Wang Q, Bao Y.et al. (2011BikDD eliminates breast cancer initiating cells and synergizes with lapatinib for breast cancer treatment Cancer Cell 20341–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peurala H, Greco D, Heikkinen T, Kaur S, Bartkova J, Jamshidi M.et al. (2011MiR-34a expression has an effect for lower risk of metastasis and associates with expression patterns predicting clinical outcome in breast cancer PLoS ONE 6e26122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix M, Toillon RA., and, Leclercq G. p53 and breast cancer, an update. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13:293–325. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasinski AL., and, Slack FJ. Epigenetics and genetics. MicroRNAs en route to the clinic: progress in validating and targeting microRNAs for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:849–864. doi: 10.1038/nrc3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T, Huang X, Gu J, Zhang L, Roth JA, Xiong M.et al. (2002Long-term tumor-free survival from treatment with the GFP-TRAIL fusion gene expressed from the hTERT promoter in breast cancer cells Oncogene 218020–8028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Adams JY, Billick E, Ilagan R, Iyer M, Le K.et al. (2002Molecular engineering of a two-step transcription amplification (TSTA) system for transgene delivery in prostate cancer Mol Ther 5223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer M, Salazar FB, Lewis X, Zhang L, Carey M, Wu L.et al. (2004Noninvasive imaging of enhanced prostate-specific gene expression using a two-step transcriptional amplification-based lentivirus vector Mol Ther 10545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufferey R, Donello JE, Trono D., and, Hope TJ. Woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element enhances expression of transgenes delivered by retroviral vectors. J Virol. 1999;73:2886–2892. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2886-2892.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao J, Salari K, Bocanegra M, Choi YL, Girard L, Gandhi J.et al. (2009Molecular profiling of breast cancer cell lines defines relevant tumor models and provides a resource for cancer gene discovery PLoS ONE 4e6146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zöller M. CD44: can a cancer-initiating cell profit from an abundantly expressed molecule. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:254–267. doi: 10.1038/nrc3023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elangovan S, Ramachandran S, Venkatesan N, Ananth S, Gnana-Prakasam JP, Martin PM.et al. (2011SIRT1 is essential for oncogenic signaling by estrogen/estrogen receptor a in breast cancer Cancer Res 716654–6664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RH, Zheng Y, Kim HS, Xu X, Cao L, Luhasen T.et al. (2008Interplay among BRCA1, SIRT1, and Survivin during BRCA1-associated tumorigenesis Mol Cell 3211–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singletary SE, Allred C, Ashley P, Bassett LW, Berry D, Bland KI.et al. (2003Staging system for breast cancer: revisions for the 6th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual Surg Clin North Am 83803–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson JR, Weaver DL, Mittra I., and, Hayashi M. The TNM staging system and breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:56–60. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)00961-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira J., and, Messing J. New pUC-derived cloning vectors with different selectable markers and DNA replication origins. Gene. 1991;100:189–194. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90365-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CH, Lee SW, Li CF, Wang J, Yang WL, Wu CY.et al. (2010Deciphering the transcriptional complex critical for RhoA gene expression and cancer metastasis Nat Cell Biol 12457–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Templeton NS, Lasic DD, Frederik PM, Strey HH, Roberts DD., and, Pavlakis GN. Improved DNA: liposome complexes for increased systemic delivery and gene expression. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:647–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt0797-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramantieri L, Ferracin M, Fornari F, Veronese A, Sabbioni S, Liu CG.et al. (2007Cyclin G1 is a target of miR-122a, a microRNA frequently down-regulated in human hepatocellular carcinoma Cancer Res 676092–6099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombe DR, Nakhoul AM, Stevenson SM, Peroni SE., and, Sanderson CJ. Expressed luciferase viability assay (ELVA) for the measurement of cell growth and viability. J Immunol Methods. 1998;215:145–150. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Size and zeta potential of plasmid:liposome nanoparticles (N/P = 2:1).

The relationship between miR-34a expression and clinicopathological parameters in breast cancer.